Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

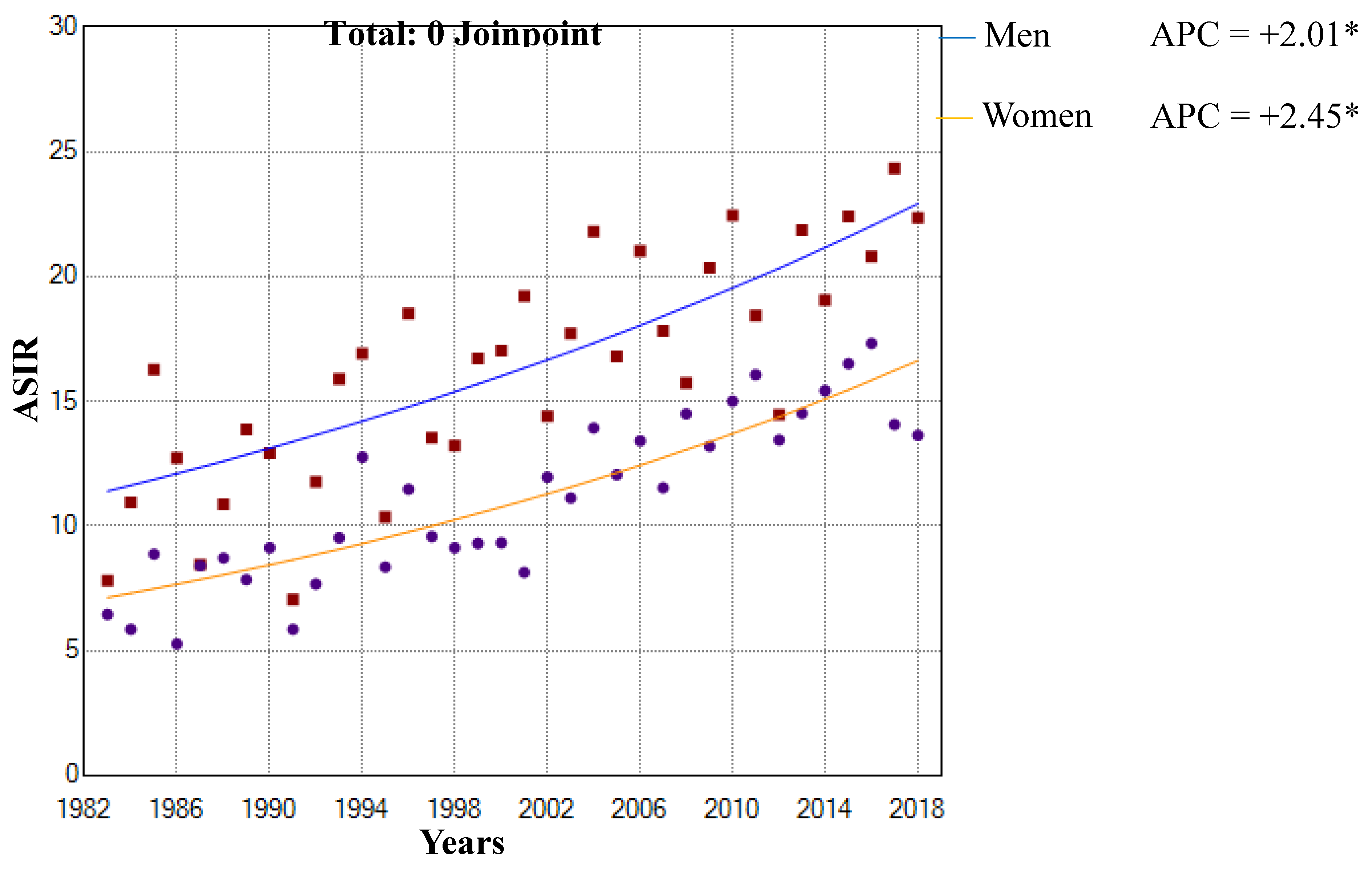

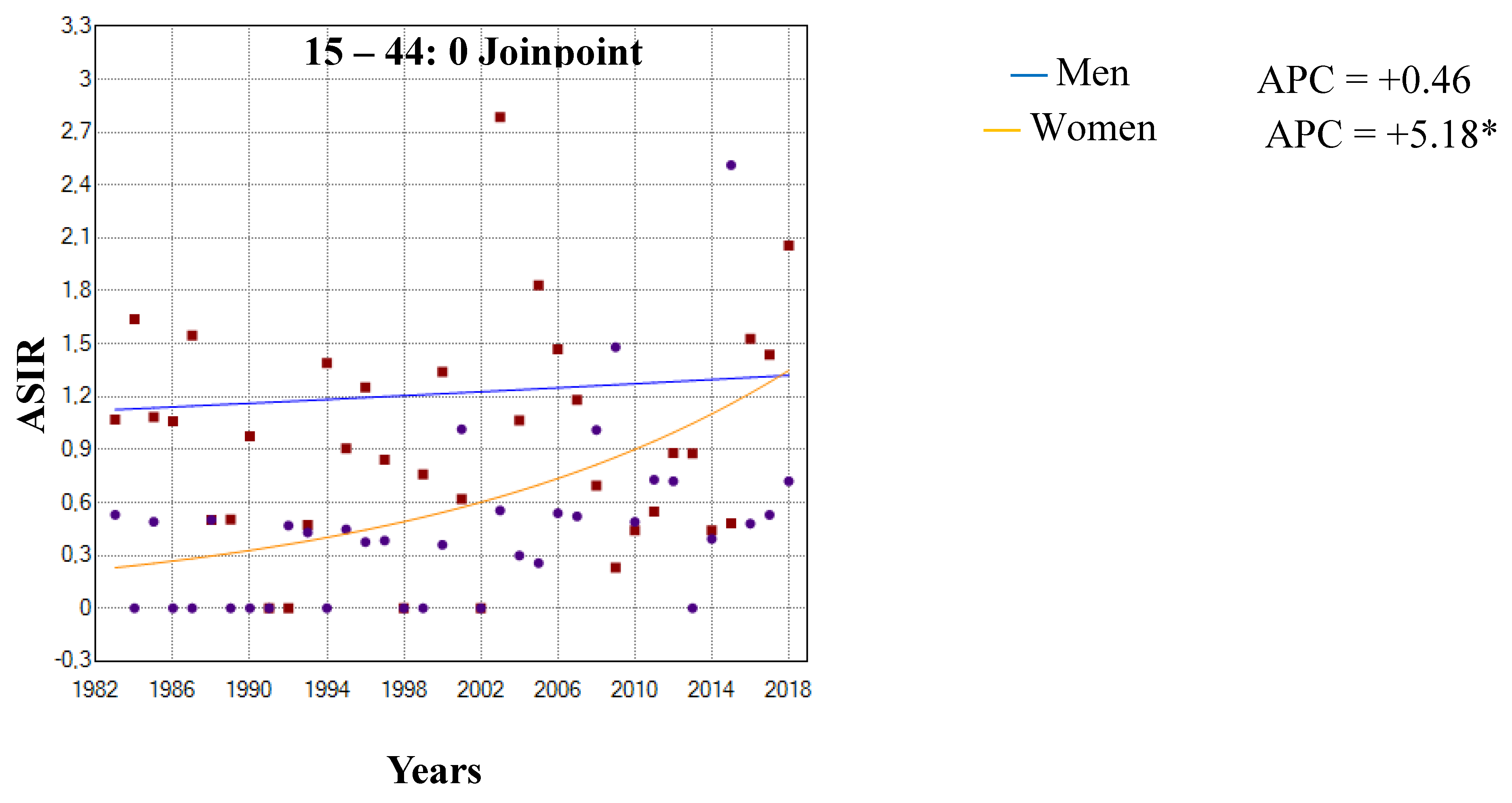

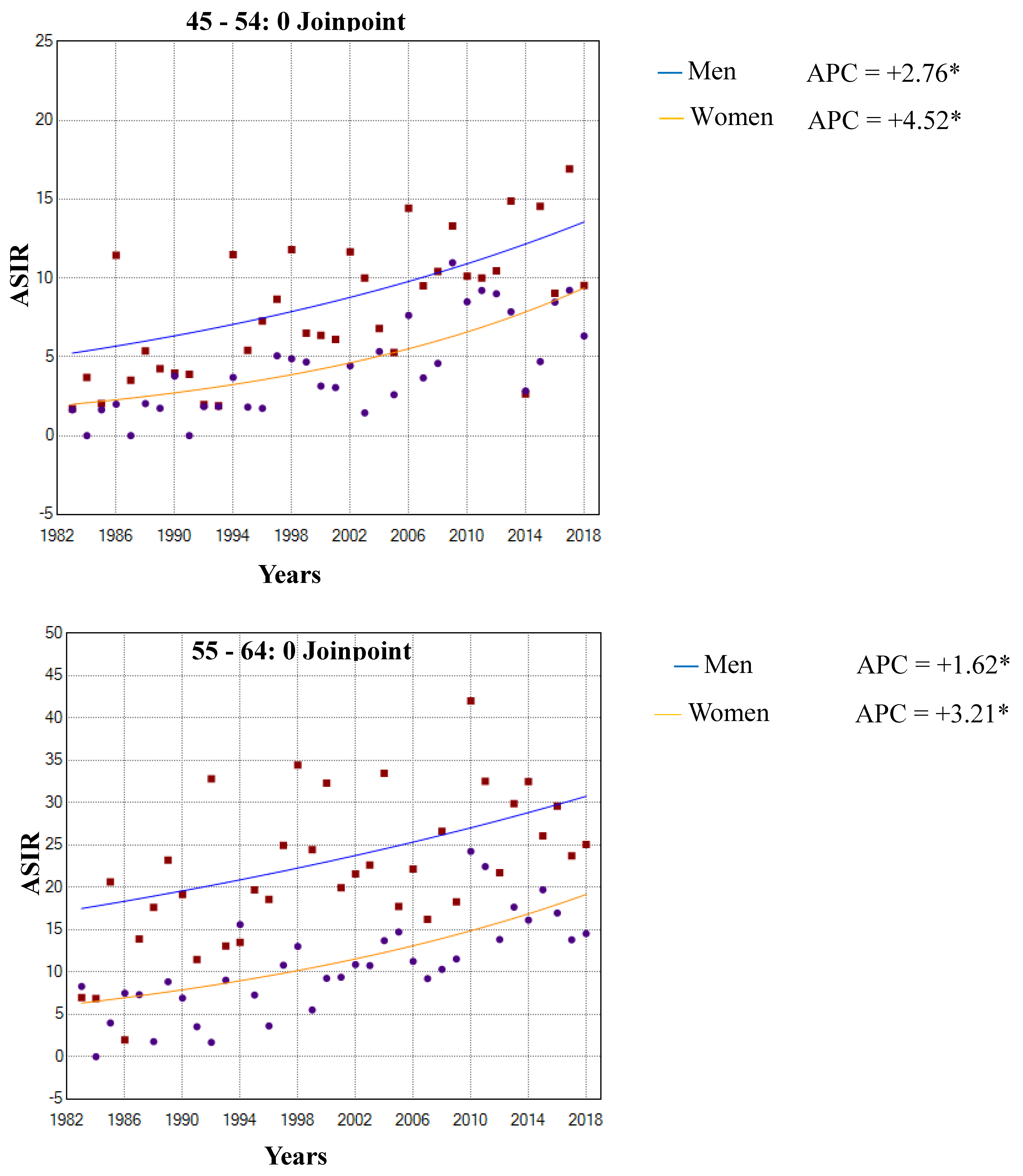

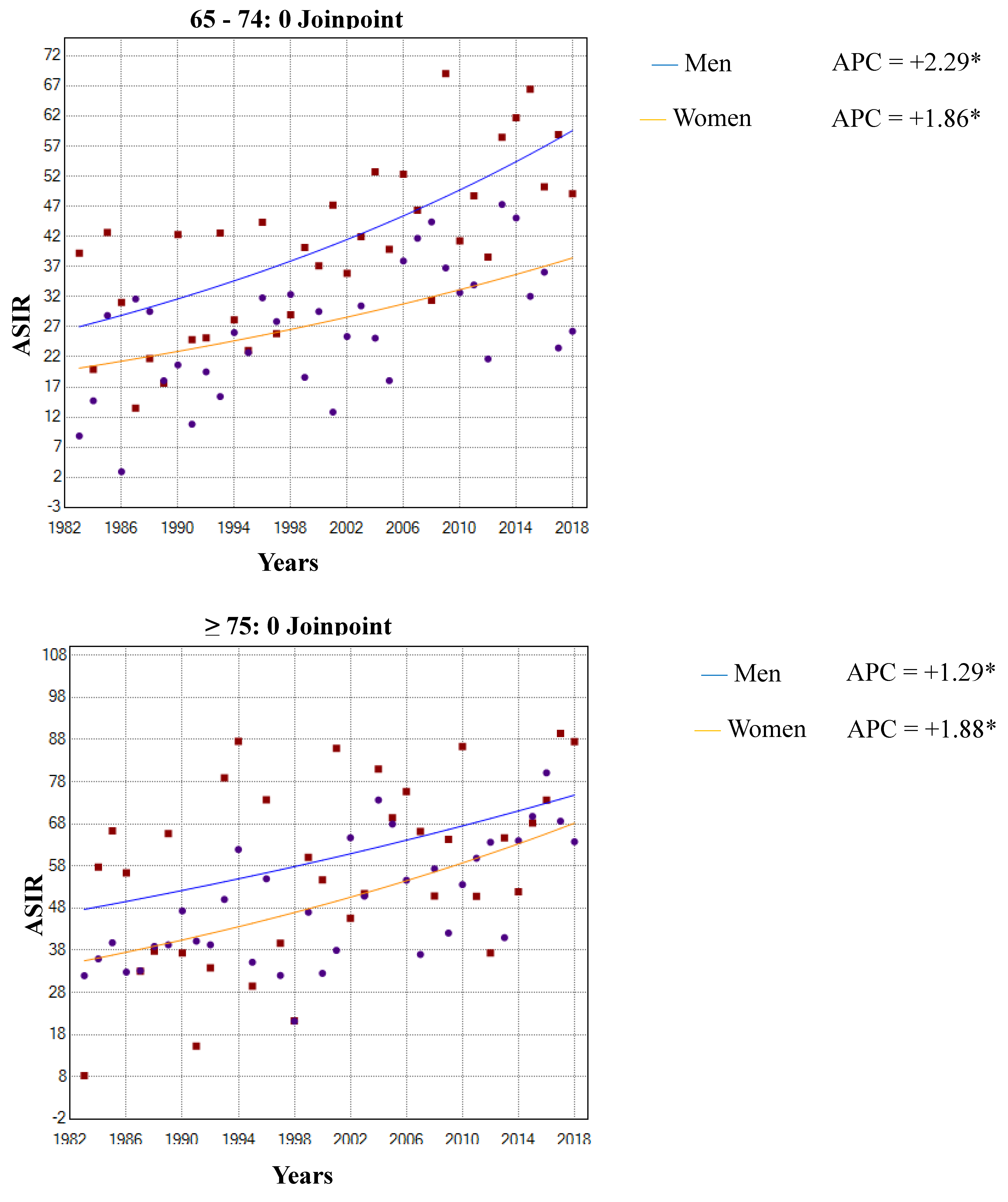

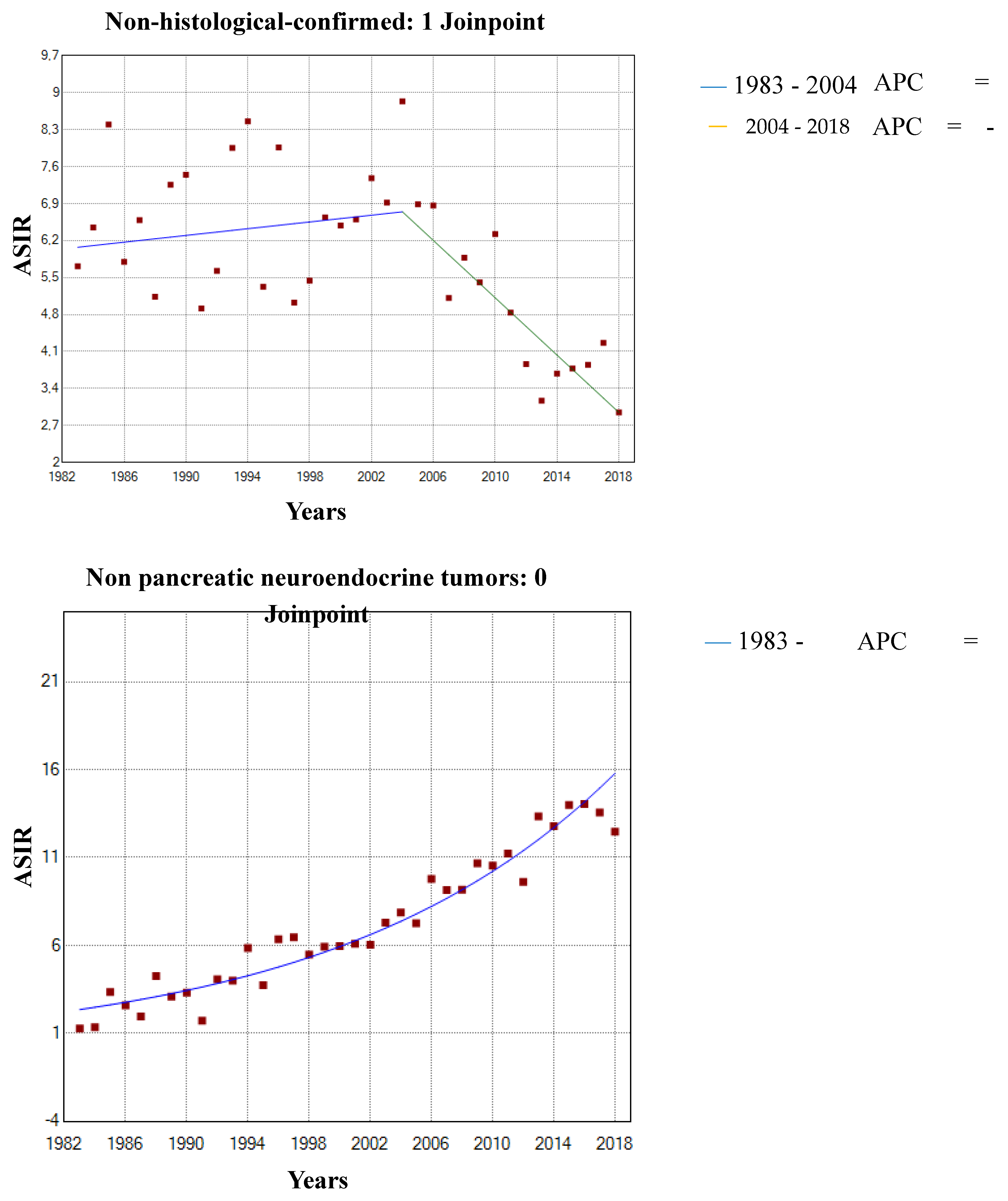

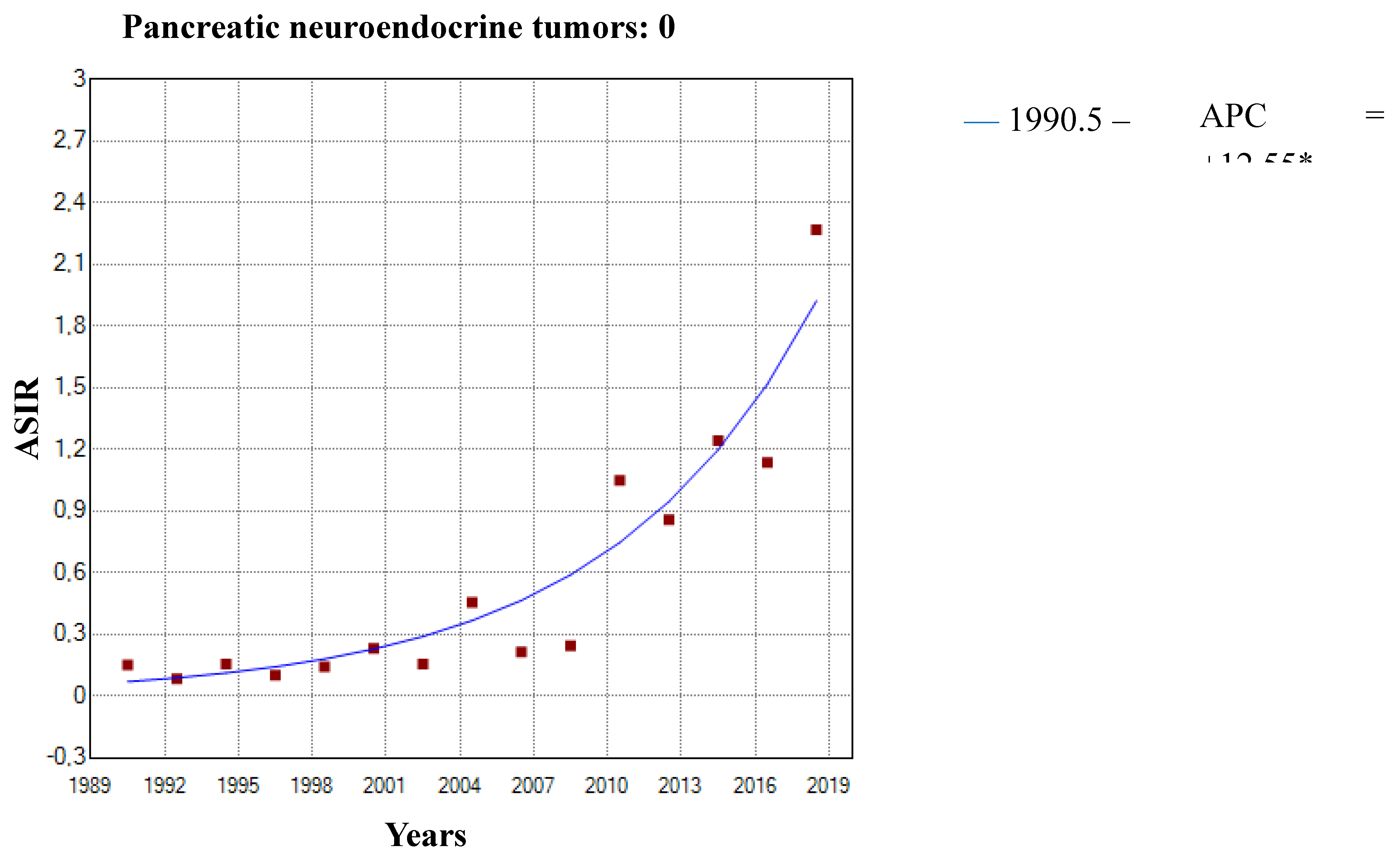

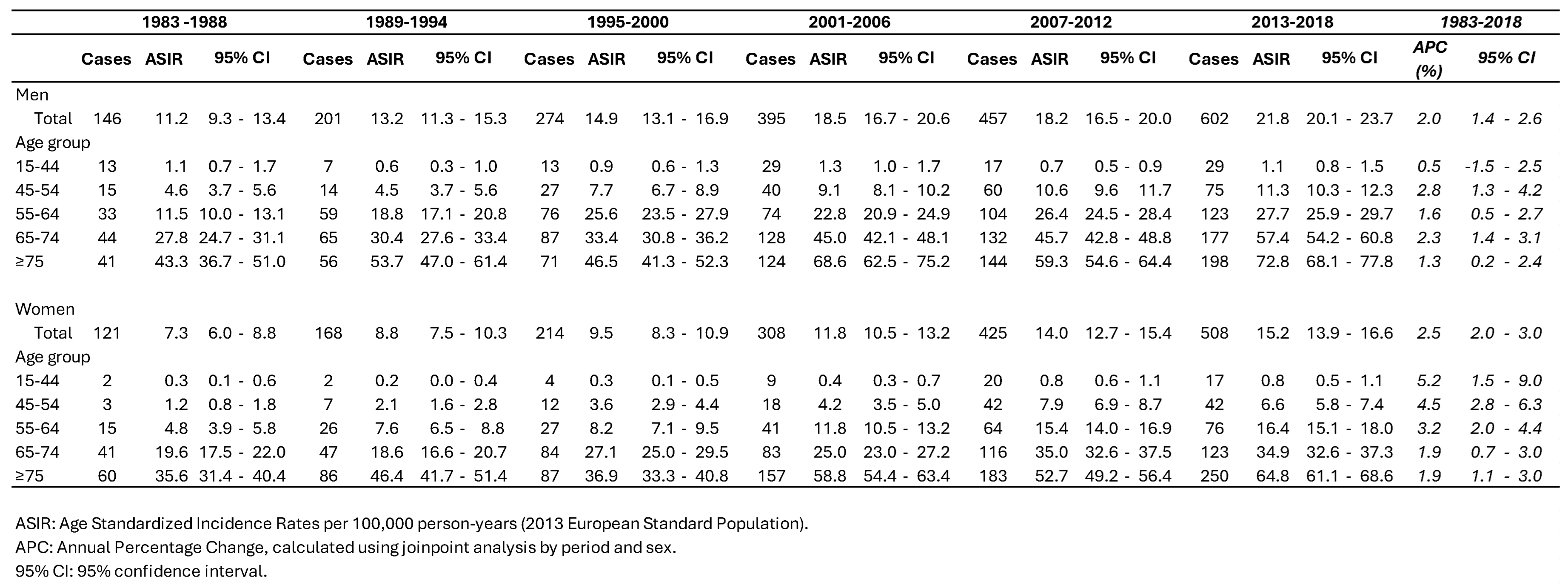

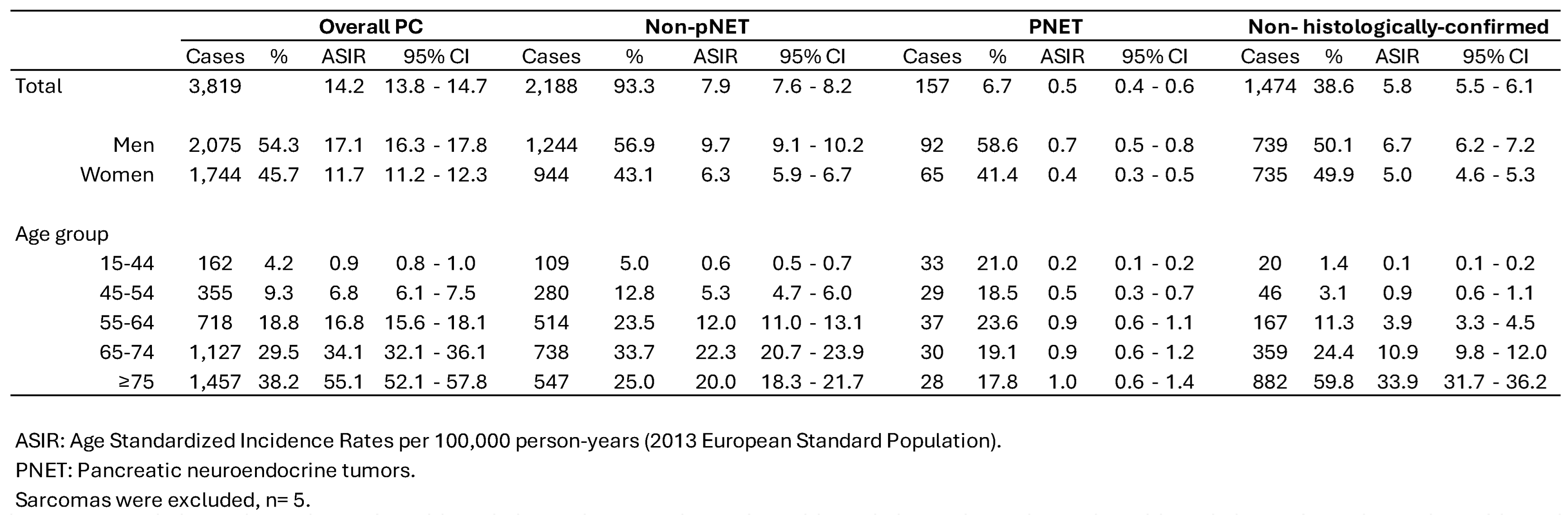

3.1. Incidence Trends

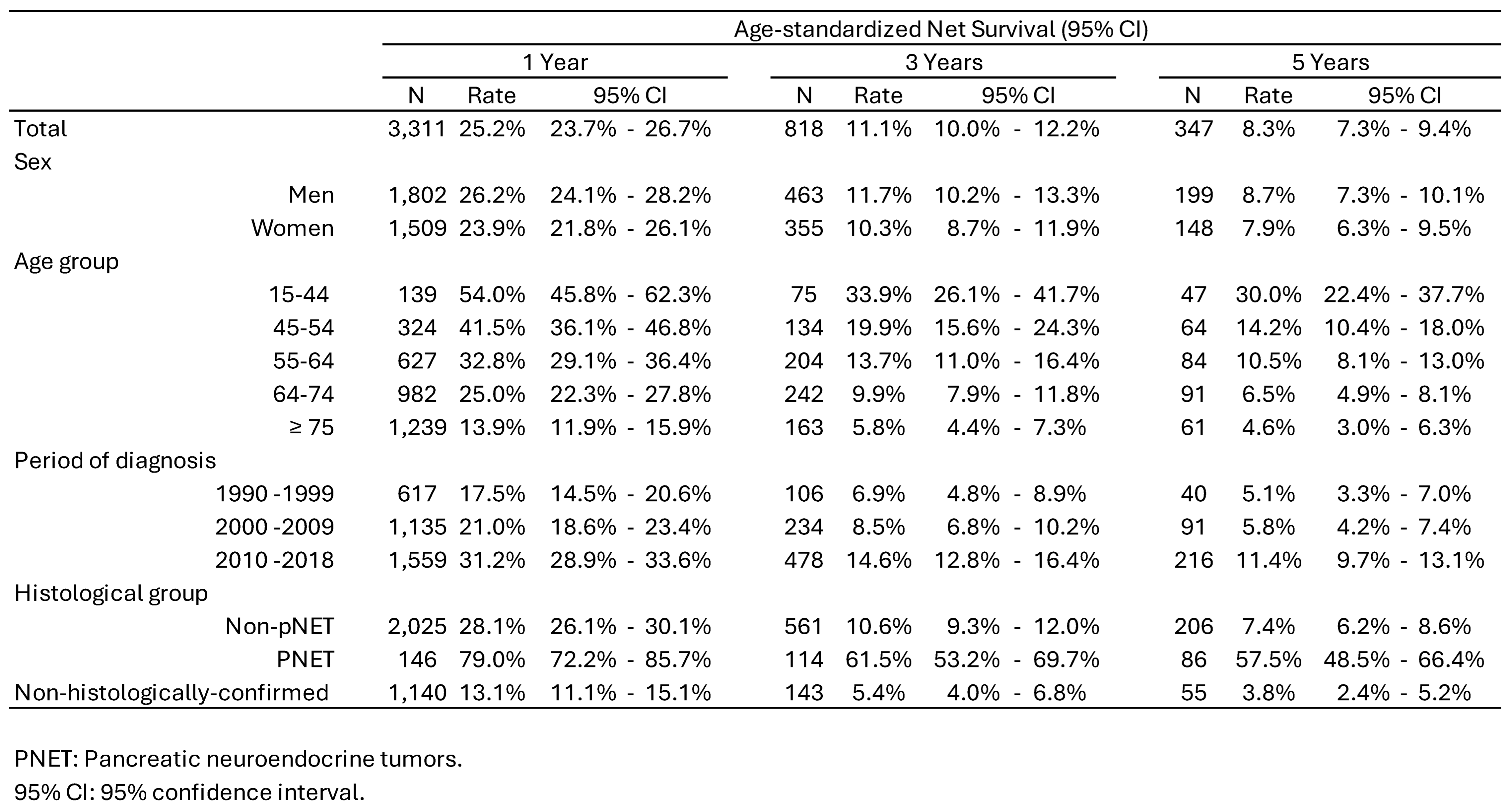

3.2. Survival Trends

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2024, 74, 229–263. [CrossRef]

- Red Española de Registros de Cáncer; REDECAN 2024. Estimaciones de La Incidencia de Cáncer En España, 2024. Available online: https://redecan.org/es/proyectos/15/estimaciones-de-la-incidencia-del-cancer-en-espana-2023.

- Guevara, M.; Molinuevo, A.; Salmerón, D.; Marcos-Gragera, R.; Carulla, M.; Chirlaque, M.-D.; Rodríguez Camblor, M.; Alemán, A.; Rojas, D.; Vizcaíno Batllés, A.; et al. Cancer Survival in Adults in Spain: A Population-Based Study of the Spanish Network of Cancer Registries (REDECAN). Cancers 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Pancreatic Cancer. Continuous Update Project 2018. Available: Dietandcancerreport.Org; Available at dietandcancerreport.org, 2018;

- Naudin, S.; Li, K.; Jaouen, T.; Assi, N.; Kyro, C.; Tjonneland, A.; Overvad, K.; Boutron-Ruault, M.-C.; Rebours, V.; Vedie, A.-L.; et al. Lifetime and Baseline Alcohol Intakes and Risk of Pancreatic Cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Study. International journal of cancer 2018, 143, 801–812. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Montes, E.; Van Hoogstraten, L.; Gomez-Rubio, P.; Löhr, M.; Sharp, L.; Molero, X.; Márquez, M.; Michalski, C.W.; Farré, A.; Perea, J.; et al. Pancreatic Cancer Risk in Relation to Lifetime Smoking Patterns, Tobacco Type, and Dose-Response Relationships. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2020, 29, 1009–1018. [CrossRef]

- Porta, M.; Gasull, M.; Pumarega, J.; Kiviranta, H.; Rantakokko, P.; Raaschou-Nielsen, O.; Bergdahl, I.A.; Sandanger, T.M.; Agudo, A.; Rylander, C.; et al. Plasma Concentrations of Persistent Organic Pollutants and Pancreatic Cancer Risk. International Journal of Epidemiology 2022, 51, 479–490. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dyba, T.; Randi, G.; Bettio, M.; Gavin, A.; Visser, O.; Bray, F. Cancer Incidence and Mortality Patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 Countries and 25 Major Cancers in 2018. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2018, 103, 356–387. [CrossRef]

- Cavazzani, A.; Angelini, C.; Gregori, D.; Cardone, L. Cancer Incidence (2000-2020) among Individuals under 35: An Emerging Sex Disparity in Oncology. BMC medicine 2024, 22, 363. [CrossRef]

- Abboud, Y.; Samaan, J.S.; Oh, J.; Jiang, Y.; Randhawa, N.; Lew, D.; Ghaith, J.; Pala, P.; Leyson, C.; Watson, R.; et al. Increasing Pancreatic Cancer Incidence in Young Women in the United States: A Population-Based Time-Trend Analysis, 2001-2018. Gastroenterology 2023, 164, 978-989.e6. [CrossRef]

- Sakai, Y.; Honda, M.; Matsui, S.; Komori, O.; Murayama, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Mizuno, M.; Imai, Y.; Yoshimura, K.; Nasti, A.; et al. Development of Novel Diagnostic System for Pancreatic Cancer, Including Early Stages, Measuring MRNA of Whole Blood Cells. Cancer science 2019, 110, 1364–1388. [CrossRef]

- Owens, D.K.; Davidson, K.W.; Krist, A.H.; Barry, M.J.; Cabana, M.; Caughey, A.B.; Curry, S.J.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W.J.; Kubik, M.; et al. Screening for Pancreatic Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2019, 322, 438–444. [CrossRef]

- Stang, A.; Wellmann, I.; Holleczek, B.; Fell, B.; Terner, S.; Lutz, M.P.; Kajüter, H. Incidence and Relative Survival of Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma and Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms in Germany, 2009-2018. An in-Depth Analysis of Two Population-Based Cancer Registries. Cancer epidemiology 2022, 79, 102204. [CrossRef]

- Galceran, J.; Ameijide, A.; Carulla, M.; Mateos, A.; Quiros, J.R.; Rojas, D.; Aleman, A.; Torrella, A.; Chico, M.; Vicente, M.; et al. Cancer Incidence in Spain, 2015. Clinical & translational oncology : official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico 2017, 19, 799–825. [CrossRef]

- Centro Regional de Estadística de la Región de Murcia Padrón Municipal de Habitantes.

- Bray F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Z.R. and F.J. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Vol. XI (Electronic Version). (IARC Scientific Publication No. 166).

- IACR-ENCR. International Rules for Multiple Primary Cancers (ICD-O 3rd Ed). Lyon: IACR. 2004.

- Ferlay J, Burkhard C, Whelan S, P.D. Check Conversion Programs for Cancer Registries. (IARC/IACR Tools for Cancer Registries).; Lyon, France: IARC, 2005;

- De Angelis, R.; Francisci, S.; Baili, P.; Marchesi, F.; Roazzi, P.; Belot, A.; Crocetti, E.; Pury, P.; Knijn, A.; Coleman, M.; et al. The EUROCARE-4 Database on Cancer Survival in Europe: Data Standardisation, Quality Control and Methods of Statistical Analysis. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2009, 45, 909–930. [CrossRef]

- Regulation General Data Protection. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- European Network of Cancer Registries. Guidelines on Confidentiality in Population- Based Cancer Registration in the European Union. Lyon 2002.

- Breslow, N.E.; Day, N.E. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research. Volume II--The Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies. IARC scientific publications 1987, 1–406.

- Commission., E. Revision of the European Standard Population—Report of Eurostat’s Task Force. 2013.

- Perme, M.P.; Henderson, R.; Stare, J. An Approach to Estimation in Relative Survival Regression. Biostatistics (Oxford, England) 2009, 10, 136–146. [CrossRef]

- Corazziari, I.; Quinn, M.; Capocaccia, R. Standard Cancer Patient Population for Age Standardising Survival Ratios. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2004, 40, 2307–2316. [CrossRef]

- Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.6.0.0 - April 2018; Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, N.C.I. No Title 2018.

- Gaddam, S.; Abboud, Y.; Oh, J.; Samaan, J.S.; Nissen, N.N.; Lu, S.C.; Lo, S.K. Incidence of Pancreatic Cancer by Age and Sex in the US, 2000-2018. JAMA 2021, 326, 2075–2077. [CrossRef]

- Samaan, J.S.; Abboud, Y.; Oh, J.; Jiang, Y.; Watson, R.; Park, K.; Liu, Q.; Atkins, K.; Hendifar, A.; Gong, J.; et al. Pancreatic Cancer Incidence Trends by Race, Ethnicity, Age and Sex in the United States: A Population-Based Study, 2000-2018. Cancers 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Keyes, K.M.; Jager, J.; Mal-Sarkar, T.; Patrick, M.E.; Rutherford, C.; Hasin, D. Is There a Recent Epidemic of Women’s Drinking? A Critical Review of National Studies. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 2019, 43, 1344–1359. [CrossRef]

- García-Velasco, A.; Zacarías-Pons, L.; Teixidor, H.; Valeros, M.; Liñan, R.; Carmona-Garcia, M.C.; Puigdemont, M.; Carbajal, W.; Guardeño, R.; Malats, N.; et al. Incidence and Survival Trends of Pancreatic Cancer in Girona: Impact of the Change in Patient Care in the Last 25 Years. International journal of environmental research and public health 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Abboud, Y.; Liang, J.; Larson, B.; Osipov, A.; Gong, J.; Hendifar, A.E.; Atkins, K.; Liu, Q.; Nissen, N.N.; et al. The Disproportionate Rise in Pancreatic Cancer in Younger Women Is Due to a Rise in Adenocarcinoma and Not Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Nationwide Time-Trend Analysis Using 2001-2018 United States Cancer Statistics Databases. Cancers 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jansen, L.; Balavarca, Y.; Babaei, M.; van der Geest, L.; Lemmens, V.; Van Eycken, L.; De Schutter, H.; Johannesen, T.B.; Primic-Žakelj, M.; et al. Stratified Survival of Resected and Overall Pancreatic Cancer Patients in Europe and the USA in the Early Twenty-First Century: A Large, International Population-Based Study. BMC medicine 2018, 16, 125. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jun; Xiao, Yu-Xuan; Li, Zhuo-Ying; Zou, Yi-Xin; Zhou, Xiao-Hui; Zhang, Wei; Li, Hong-Lan; Qu, Xu; Xiang, Y.-B. Global Characteristics of Pancreatic Cancer Survival: A Comprehensive Overview of Survival Analysis from Cancer Registration Data. Journal of Pancreatology.

- Bouvier, A.-M.; Bossard, N.; Colonna, M.; Garcia-Velasco, A.; Carulla, M.; Manfredi, S. Trends in Net Survival from Pancreatic Cancer in Six European Latin Countries: Results from the SUDCAN Population-Based Study. European journal of cancer prevention : the official journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation (ECP) 2017, 26 Trends, S63–S69. [CrossRef]

- Blackford, A.L.; Canto, M.I.; Klein, A.P.; Hruban, R.H.; Goggins, M. Recent Trends in the Incidence and Survival of Stage 1A Pancreatic Cancer: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Analysis. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2020, 112, 1162–1169. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2020. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2020, 70, 7–30. [CrossRef]

- McGuigan, A.; Kelly, P.; Turkington, R.C.; Jones, C.; Coleman, H.G.; McCain, R.S. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review of Clinical Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Treatment and Outcomes. World journal of gastroenterology 2018, 24, 4846–4861. [CrossRef]

- Halbrook, C.J.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Pasca di Magliano, M.; Maitra, A. Pancreatic Cancer: Advances and Challenges. Cell 2023, 186, 1729–1754. [CrossRef]

- Del Chiaro, M.; Sugawara, T.; Karam, S.D.; Messersmith, W.A. Advances in the Management of Pancreatic Cancer. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2023, 383, e073995. [CrossRef]

- Nikšić, M.; Matz, M.; Valkov, M.; Marcos-Gragera, R.; Stiller, C.; Rosso, S.; Coleman, M.P.; Allemani, C. World-Wide Trends in Net Survival from Pancreatic Cancer by Morphological Sub-Type: An Analysis of 1,258,329 Adults Diagnosed in 58 Countries during 2000-2014 (CONCORD-3). Cancer epidemiology 2022, 80, 102196. [CrossRef]

- Kenney, L.M.; Hughes, M. Surgical Management of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancers 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Benderli Cihan, Y. Are PNETs Radiotherapy Resistant? Turkish journal of surgery 2020, 36, 238–239. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).