Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

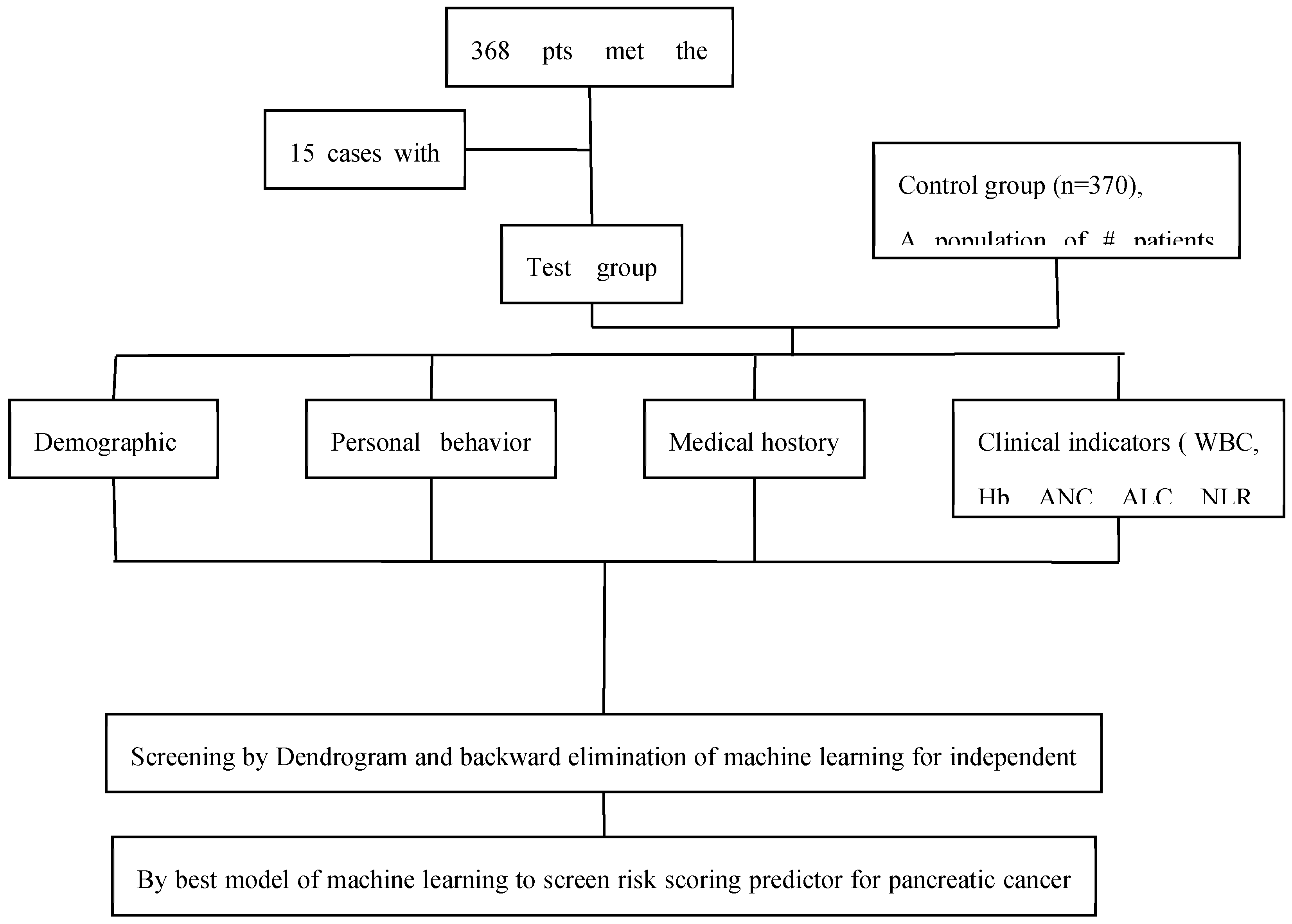

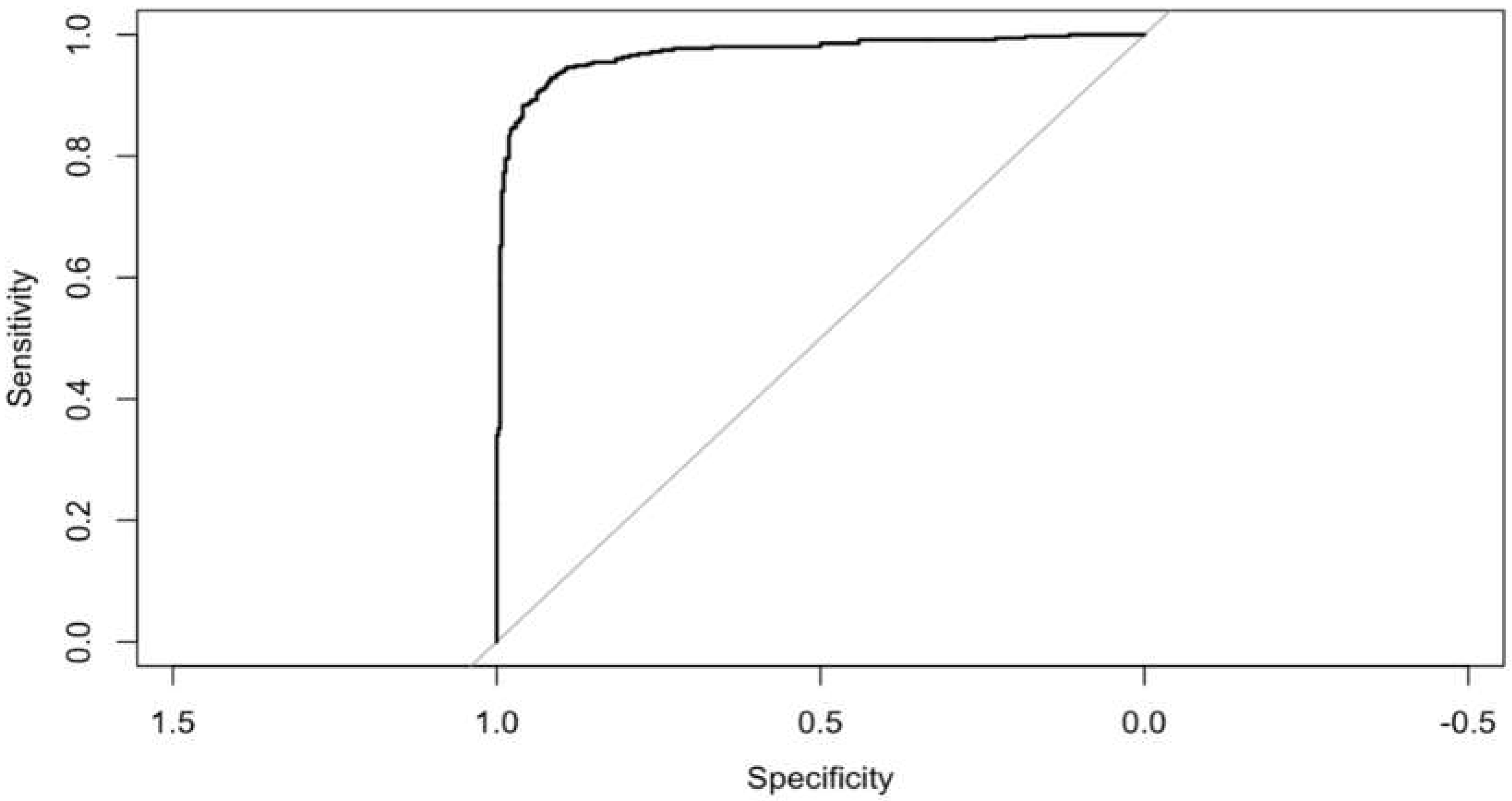

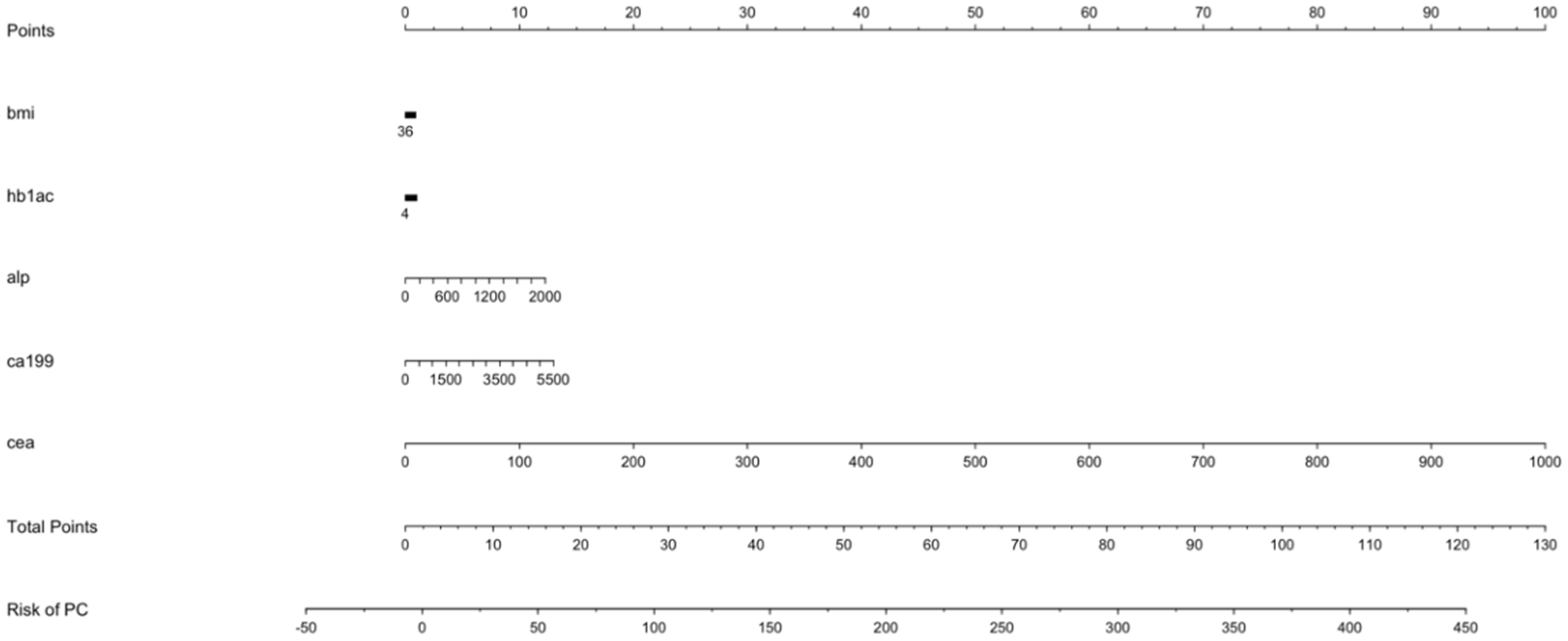

Introduction: Particularly pancreatic cancer, poses a significant global health challenge due to its high mortality rates despite advancements in treatment. Early detection remains crucial as most cases are diagnosed at late stages when surgical intervention is no longer viable. We focused to identify relevant risk factors of pancreatic cancer. Our goal was to determine pertinent risk factors for pancreatic cancer. The best machine learning model was used for risk scoring in pancreatic cancer based on those risk factors and determine their diagnostic value. Methods: We conducted a matched case-control study, retrospectively collecting demographic data and common haemato-logical indicators from all participants. Best model of machine learning among SVM and Logistic regression was chosen to identify risk factors for pancreatic cancer after initial variable selection by dendrogram. Based on these factors, we created a best model for risk scoring in pancreatic cancer and showed higher diagnostic value. Result: 353 cases and 370 controls were finally participated in our study. The discoveries of our machine learning logistic regression with backward elimination showed that Haemoglobin A1c (OR 1.28, 95%CI: 1.08,1.52), Alkaline phosphatase (OR 1.02, 95%CI: 1.01,1.03), CA19-9 (OR 1.01, 95%CI: 1.01,1.01), and Carcinoembryonic antigen (OR 1.41, 95%CI: 1.2,1.66) were related to an expanded risk of PC, while BMI (OR 0.88, 95%CI: 0.81,0.97) were asso-ciated with a diminished risk of PC. Based on these outcomes, the clinical PC for risk scoring was well fitted in the modelled populace, and the score had strong predictive worth with area under receiver operating curve was 0.969 (P < 0.001) which showed higher diagnostic value. Conclusion: HbA1C, ALP, BMI, CA19-9 and CEA levels were associated with the risk of PC. The risk scoring scale (nomogram) might be useful in clinical PC screening as a diagnostic tool by supervised ma-chine learning.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Inclusion Exclusion Criteria

- ➢

- All patients who met primary screening criteria are included.

- ➢

- Blood tests of first visit after pancreatic cancer diagnosis prior to start of treatment.

- ➢

- Age more than 18 years are included

- ➢

- Pancreatic cancers patients associated with other malignant tumor were not included.

- ➢

- Patients with incomplete data information were excluded.

- ➢

- Ages less than 18 year are excluded.

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Information of the Study Participants

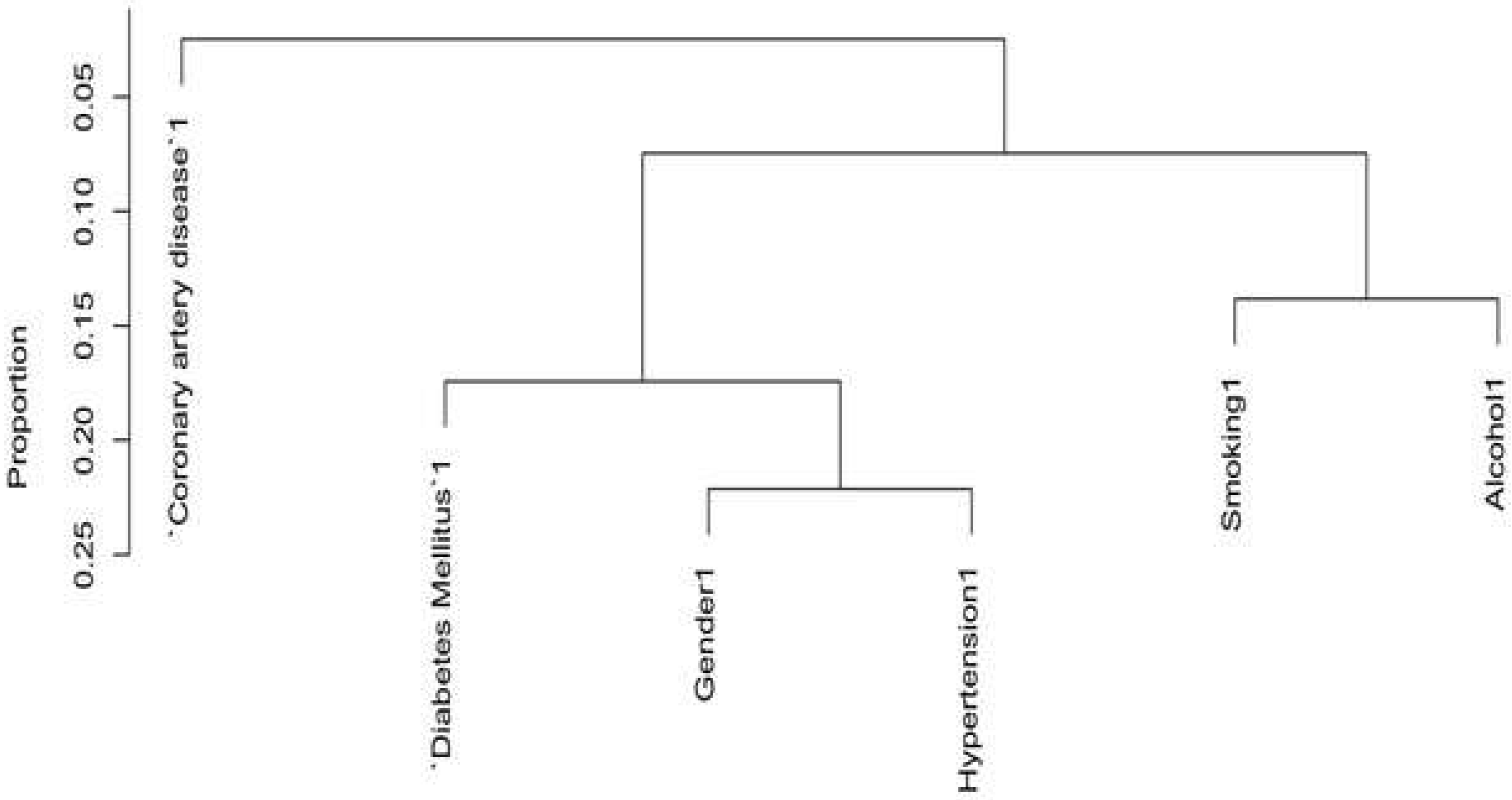

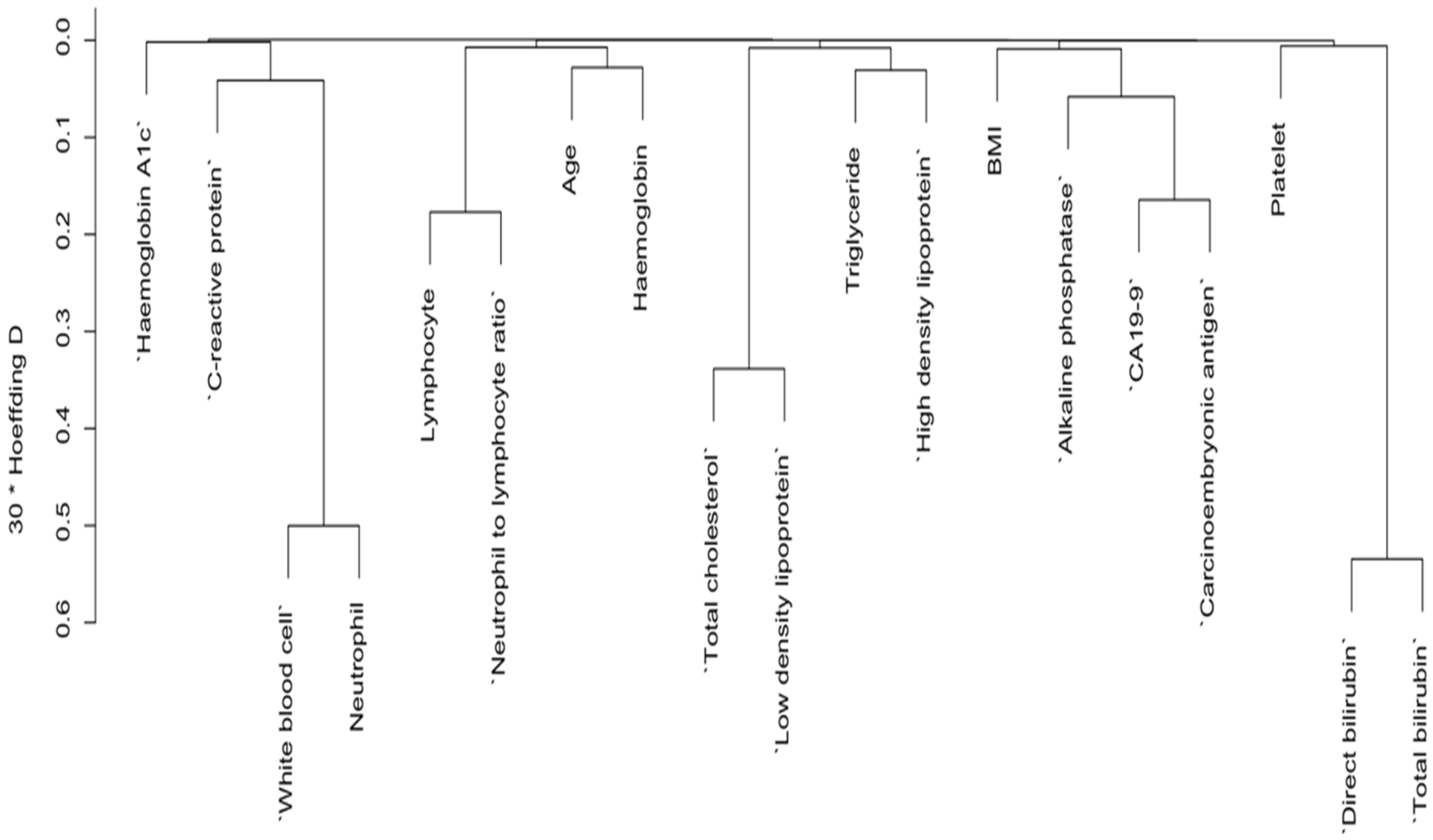

3.2. Variables Selection for Risk of Pancreatic Cancer by Dendrogram Cluster Analysis for Both Categorical and Continuous Predictors

3.3. Further Variable Selection by Backward Elimination and Features Importance Ranked

3.4. Odd Ratio for Final Variables by Logistic Regression

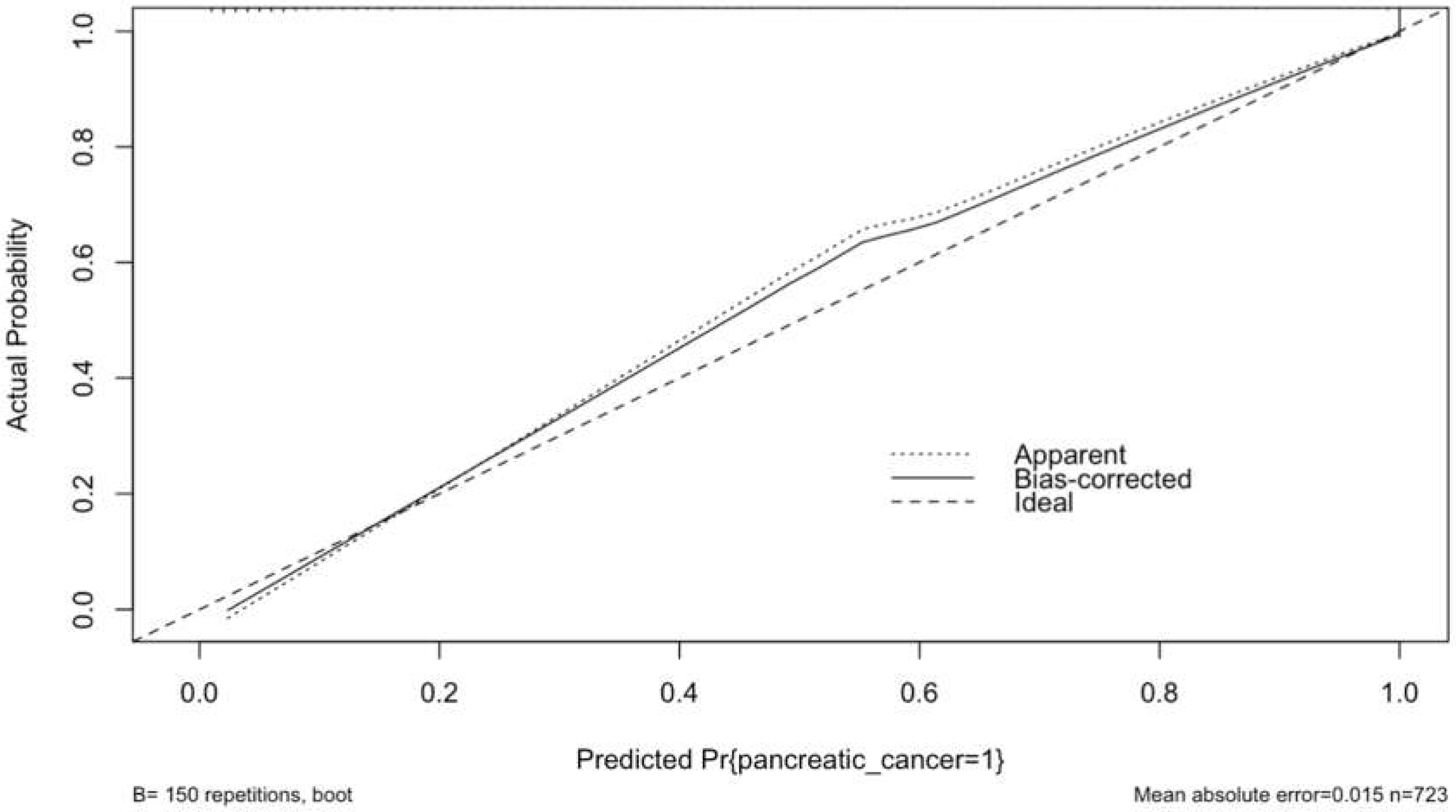

3.5. Calibration Plot with Internal Validation from Logistic Regression

3.6. Final Model Performance

3.7. Points Predictor in Nomogram for Pancreatic Cancer

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Stewart BW and Wild CP (eds): World Cancer Report 2014. IARC Press, Lyon, 2014.

- World Health Organization World Health Organization Statistical Information System. WHO Mortality Database. 2012.

- Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Levi F, La Vecchia C, Negri E. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2013. Ann Oncol. 2013; 24(3):792–800. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Chen, H.; Lu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, B.; You, L.; Zhang, T.; Dai, M.; Zhao, Y. Advances in the epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: Trends, risk factors, screening, and prognosis. Cancer Lett. 2021, 520, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R. L. , Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E., & Jemal, A. (2022). Cancer statistics, 2022. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 72(1), 7–33. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R. L. , Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E., & Jemal, A. (2021). Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 71(1), 7–33. [CrossRef]

- Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: The unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014; 74: 2913–21. [CrossRef]

- Bo, X. , Shi, J., Liu, R., Geng, S., Li, Q., Li, Y., Jin, H., Yang, S., Jiang, H., & Wang, Z. (2019). Using the Risk Factors of Pancreatic Cancer and Their Interactions in Cancer Screening: A Case-Control Study in Shanghai, China. Annals of global health, 85(1), 103. [CrossRef]

- P. Rawla, T. Sunkara, and V. Gaduputi, "Epidemiology of Pancreatic Cancer: Global Trends, Etiology and Risk Factors," World Journal of Oncology, vol. 10, pp. 10–27, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Bond-Smith et al., "Pancreatic adenocarcinoma," BMJ, vol. 344, p. e2476, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Woodmansey, C. , et al., Incidence, Demographics, and Clinical Characteristics of Diabetes of the Exocrine Pancreas (Type 3c): A Retrospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Care, 2017. 40(11): p. 1486–1493. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, S.H. , et al., Weight Loss, Diabetes, Fatigue, and Depression Preceding Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas, 2016. 45(7): p. 986–91. [CrossRef]

- Hippisley-Cox, J. and Coupland C., Identifying patients with suspected pancreatic cancer in primary care: derivation and validation of an algorithm. Br J Gen Pract, 2012. 62(594): p. e38–45. [CrossRef]

- S. Midha, S. S. Midha, S. Chawla, and P. K. Garg, "Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for pancreatic cancer: A review," Cancer Letters, vol. 381, pp. 269–277, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Lang et al., "Risk factors of pancreatic cancer and their possible uses in diagnostics," Neoplasma, vol. 68, pp. 227–239, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Koo DH, Han KD, Park CY. The Incremental Risk of Pancreatic Cancer According to Fasting Glucose Levels: Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2019; 104(10):4594–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawla P, Sunkara T, Gaduputi V. Epidemiology of Pancreatic Cancer: Global Trends, Etiology and Risk Factors. World journal of oncology. 2019; 10(1):10–27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flechon A, Pouessel D, Ferlay C, Perol D, Beuzeboc P, Gravis G, et al. Phase II study of carboplatin andetoposide in patients with anaplastic progressive metastatic castrationresistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) with or without neuroendocrine differentiation: results of the French Genito-urinary tumor group (GETUG) P01 trial. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2476–81. [CrossRef]

- Sonpavde G, Pond GR, Berry WR, de Wit R, Armstrong AJ, Eisenberger MA, et al. Serum alkaline phosphatase changes predict survival independent of PSA changes in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastasis receiving chemotherapy. Urol Oncol. 2012;30:607–13. [CrossRef]

- Mikah P, Krabbe LM, Eminaga O, Herrmann E, Papavassilis P, Hinkelammert R, et al. Dynamic changes of alkaline phosphatase are strongly associated with PSA-decline and predict best clinical benefit earlier than PSA-changes under therapy with abiraterone acetate in bone metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:214. [CrossRef]

- Hung HY, Chen JS, Yeh C-Y, Tang R, Hsieh PS, Tasi W-S, et al. Preoperative alkaline phosphatase elevation was associated with poor survival in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Color Dis. 2017;32:1775–8. [CrossRef]

- Chen B, Dai D, Tang H, Chen X, Ai X, Huang X, et al. Pre-treatment serum alkaline phosphatase and lactate dehydrogenase as prognostic factors in triple negative breast cancer. J Cancer. 2016;7:2309–16. [CrossRef]

- Xie Y, Wei ZB, Duan XW. Prognostic value of pretreatment serum alkaline phosphatase in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:3547–53. [CrossRef]

- Wei XL, Zhang DS, He MM, Jin Y, Wang DS, Zhou YX, et al. The predictive value of alkaline phosphatase and lactate dehydrogenase for overall survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:1879–87. [CrossRef]

- Aminian A, Karimian F, Mirsharifi R, Alibakhshi A, Hasani SM, Dashti H, et al. Correlation of serum alkaline phosphatase with clinicopathological characteristics of patients with oesophageal cancer. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17:862–6. [CrossRef]

- Gold P, Freedman SO. Specific carcinoembryonic antigens of the human digestive system. J Exp Med. 1965; 122(3):467–481. [CrossRef]

- Molina R, Barak V, van Dalen A, et al. Tumor markers in breast cancer-European Group on Tumor Markers recommendations. Tumour Biol. 2005;26(6):281–293. [CrossRef]

- Grunnet M, Sorensen JB. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) as tumor marker in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012; 76(2):138–143. [CrossRef]

- Juweid M, Sharkey RM, Behr T, et al. Improved detection of medullary thyroid cancer with radiolabeled antibodies to carcinoembryonic antigen. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(4):1209–1217. [CrossRef]

- Nazli O, Bozdag AD, Tansug T, Kir R, Kaymak E. The diagnostic importance of CEA and CA 19-9 for the early diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000; 47(36):1750–1752.

- G. Luo et al., "Roles of CA19-9 in pancreatic cancer: Biomarker, predictor and promoter," Biochimica et BiophysicaActa Reviews on Cancer, vol. 1875, p. 188409, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Luo et al., "Optimize CA19-9 in detecting pancreatic cancer by Lewis and Secretor genotyping," Pancreatology, vol. 16, pp. 1057–1062, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Jordan MI, Mitchell TM. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science. 2015; 349:255–60. [CrossRef]

- Obermeyer Z, Emanuel EJ. Predicting the Future - Big Data, Machine Learning, and Clinical Medicine New Engl J Med. 2016; 375:1216–9. [CrossRef]

- Caruana R, Niculescu-Mizil A. An Empirical Comparison of Supervised Learning Algorithms. InICML '06. New York, NY, USA. 2006. p. 161-8. [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Kunovský, L.; Kala, Z.; Trna, J. Risk factors of pancreatic cancer and their possible uses in diagnostics. Neoplasma 2021, 68, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawary, M. Role of Imaging in Diagnosing and Staging Pancreatic Cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2016, 14, 678–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.X.; Zhao, C.F.; Chen, W.B.; Liu, Q.C.; Li, Q.W.; Lin, Y.Y.; Gao, F. Pancreatic cancer: A review of epidemiology, trend, and risk factors. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 4298–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, E.J.; Newton, C.C.; Patel, A.V.; Stevens, V.L.; Islami, F.; Flanders, W.D.; Gapstur, S.M. The Association Between Body Mass Index and Pancreatic Cancer: Variation by Age at Body Mass Index Assessment. Am. J. Epidemiology 2019, 189, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arjani, S.; Saint-Maurice, P.F.; Julian-Serrano, S.; Eibl, G.; Stolzenberg-Solomon, R. Body Mass Index Trajectories Across the Adult Life Course and Pancreatic Cancer Risk. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2022, 6, pkac066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu JX, Zhao CF, Chen WB, Liu QC, Li QW, Lin YY, Gao F. Pancreatic cancer: A review of epidemiology, trend, and risk factors. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(27): 4298-4321. [CrossRef]

- Setiawan VW, Stram DO, Porcel J, Chari ST, Maskarinec G, Le Marchand L, Wilkens LR, Haiman CA, Pandol SJ, Monroe KR. Pancreatic Cancer Following Incident Diabetes in African Americans and Latinos: The Multiethnic Cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019; 111:27-33. [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Jin, K.; Deng, S.; Cheng, H.; Fan, Z.; Gong, Y.; Qian, Y.; Huang, Q.; Ni, Q.; Liu, C.; et al. Roles of CA19-9 in pancreatic cancer: Biomarker, predictor and promoter. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2021, 1875, 188409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scara, S.; Bottoni, P.; Scatena, R. CA 19-9: Biochemical and Clinical Aspects. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 867, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, C.Y. Diagnostic biomarkers for pancreatic cancer: An update. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 7862–7865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarà, S., Bottoni, P., & Scatena, R. (2015). CA 19-9: Biochemical and Clinical Aspects. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 867, 247–260. [CrossRef]

- Gold P, Freedman SO. Specific carcinoembryonic antigens of the human digestive system. J Exp Med. 1965; 122:467–481. [CrossRef]

- Luo H, Shen K, Li B, Li R, Wang Z, Xie Z. Clinical significance and diagnostic value of serum NSE, CEA, CA19-9, CA125 and CA242 levels in colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2020 Jul; 20(1):742-750. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nazli O, Bozdag AD, Tansug T, Kir R, Kaymak E. The diagnostic importance of CEA and CA 19-9 for the early diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000; 47:1750–1752.

- Satake K, Chung YS, Yokomatsu H, Nakata B, Tanaka H, Sawada T, Nishiwaki H, Umeyama K. A clinical evaluation of various tumor markers for the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Int J Pancreatol. 1990; 7:25–36. [CrossRef]

- Ermiah E, Eddfair M, Abdulrahman O, Elfagieh M, Jebriel A, Al-Sharif M, Assidi M, Buhmeida A. Prognostic value of serum CEA and CA19-9 levels in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2022 Jun 16; 17(2):126. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chari, S. T., Kelly, K., Hollingsworth, M. A., Thayer, S. P., Ahlquist, D. A., Andersen, D. K., ... & Pandol, S. J. (2015). Early detection of sporadic pancreatic cancer: summative review. Pancreas, 44(5), 693-712. [CrossRef]

- Goonetilleke, K. S., & Siriwardena, A. K. (2007). Systematic review of carbohydrate antigen (CA 19-9) as a biochemical marker in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO), 33(3), 266-270. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. E., Lee, K. T., Lee, J. K., Paik, S. W., & Rhee, J. C. (2018). Clinical usefulness of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 as a screening test for pancreatic cancer in an asymptomatic population. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 33(1), 347-353. [CrossRef]

- Ducreux, M., Sa Cunha, A., Cuhna, A.S., et al. (2019). Cancer of the pancreas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology, 30(8), 1127-1133. [CrossRef]

- Tempero, M.A., Malafa, M.P., Al-Hawary, M., et al. (2019). Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 1.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 17(3), 202-210. [CrossRef]

- Untawale, S.; Odegaard, A.O.; Koh, W.P.; Jin, A.Z.; Yuan, J.M.; Anderson, K.E. Body mass index and risk of pancreatic cancer in a Chinese population. PLoS One 2014, 9, e85149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canto, M. I. , Harinck, F., Hruban, R. H., Offerhaus, G. J. A., Poley, J. W., Kamel, I.,... & Kluijt, I. (2018). International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) Consortium summit on the management of patients with increased risk for familial pancreatic cancer. Gut, 67(2), 390-398. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Holtz, A., Gould, M., & Barlow, W. E. (2018). Validating prediction models for pancreatic cancer risk: A systematic review of the literature. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers, 27(11), 1243-1253.

- Mokdad, A.A., Murphy, C.C., Scarborough, P., et al. (2019). Trends in pancreatic cancer incidence in the United States, 2000-2015. JAMA, 322(14), 1478-1480. [CrossRef]

- Pannala, R., Leirness, J.B., Bamlet, W.R., & Basu, A. (2019). Risk factors for pancreatic cancer: A summary review of meta-analytical studies. International Journal of Cancer, 360(2), 206-215. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. E., Lee, K. T., Lee, J. K., Paik, S. W., & Rhee, J. C. (2018). Clinical usefulness of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 as a screening test for pancreatic cancer in an asymptomatic population. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 33(1), 347-353. [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, J., Zhang, Z., White, N., Rosenzweig, J., Fedarko, N., Jagannath, S.,... & Canto, M. I. (2004). Serum diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma using surface-enhanced laser desorption and ionization mass spectrometry. Clinical Cancer Research, 10(3), 860-868. [CrossRef]

- Rahib, L., Wehner, M.R., Matrisian, L.M., Nead, K.T. (2021). Estimated Projection of US Cancer Incidence and Death to 2040. JAMA Network Open, 4(4), e214708. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L., Miller, K.D., Jemal, A. (2021). Cancer statistics, 2021. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(1), 7-33. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Li, J., Liu, S., Sun, C., & Luo, G. (2020). Machine learning-based identification of potential biomarkers for the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Frontiers in oncology, 10, 1302. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10437932/.

- Balachandran, V. P., et al. (2015). Nomograms in oncology: More than meets the eye. The Lancet Oncology, 16(4), e173-e180. [CrossRef]

- García-Albéniz, X. , Hsu, J., Hernán, M.A., & Hernández-Díaz, S. (2017). The value of explicitly emulating a target trial when using real-world evidence: An application to colorectal cancer screening. European Journal of Epidemiology, 32(6), 495-500. [CrossRef]

- Vickers, A.J., Elkin, E.B., & Kattan, M.W. (2016). Method for evaluating prediction models that apply the results of randomized trials to individual patients. Trials, 17(1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Montes, E., Sánchez, M.J., Buckland, G., et al. (2020). Mediterranean diet and risk of pancreatic cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. British Journal of Cancer, 124(12), 238-246. [CrossRef]

| Predictors |

Overall, N = 7231 |

Control, n= 3701 |

Case, n = 3531 |

p-value2 |

| Gender [n, (%)] | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 375 (51.9) | 165 (44.6) | 210 (59.5) | |

| Female | 348 (48.1) | 205 (55.4) | 143 (40.5) | |

| Age (years) | 68.0 (62.0, 75.0) | 68.0 (62.0, 74.0) | 68.0 (63.0, 75.0) | 0.6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.8 (20.7, 24.8) | 23.5 (21.3, 25.8) | 22.2 (20.0, 24.1) | <0.001 |

| Smoking [n, (%)] | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 162 (22.4) | 64 (17.3) | 98 (27.8) | |

| No | 561 (77.6) | 306 (82.7) | 255 (72.2) | |

| Alcohol [n, (%)] | 0.033 | |||

| Yes | 158 (21.9) | 69 (18.6) | 89 (25.2) | |

| No | 565 (78.1) | 301 (81.4) | 264 (74.8) | |

| Diabetes Mellitus [n, (%)] | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 237 (32.8) | 83 (22.4) | 154 (43.6) | |

| No | 486 (67.2) | 287 (77.6) | 199 (56.4) | |

| Hypertension [n, (%)] | 0.8 | |||

| Yes | 326 (45.1) | 165 (44.6) | 161 (45.6) | |

| No | 397 (54.9) | 205 (55.4) | 192 (54.4) | |

| Coronary heart disease[n, (%)] | >0.9 | |||

| Yes | 87 (12.0) | 45 (12.2) | 42 (11.9) | |

| No | 636 (88.0) | 325 (87.8) | 311 (88.1) | |

| White blood cell (10 9/L) | 6.5 (5.3, 8.2) | 6.6 (5.4, 8.1) | 6.5 (5.2, 8.2) | 0.4 |

| Haemoglobin | 127.0 (114.0, 138.5) | 131.5 (119.0, 142.8) | 122.0 (109.0, 134.0) | <0.001 |

| Lymphocyte | 1.4 (1.0, 1.8) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.7) | <0.001 |

| Platelet | 210.0 (169.5, 260.0) | 215.0 (174.0, 258.0) | 207.0 (162.0, 262.0) | 0.3 |

| Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio | 3.1 (2.0, 4.9) | 2.8 (1.9, 4.2) | 3.4 (2.2, 5.6) | <0.001 |

| C-reactive protein | 6.1 (3.3, 18.9) | 4.4 (3.3, 14.1) | 8.3 (3.3, 22.8) | 0.009 |

| Haemoglobin A1c | 6.1 (5.6, 6.9) | 5.9 (5.5, 6.5) | 6.3 (5.8, 8.3) | <0.001 |

| Direct bilirubin (mmol/L) | 5.1 (3.6, 8.0) | 4.7 (3.6, 6.0) | 5.7 (3.7, 63.2) | <0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (mmol/L) | 14.6 (10.7, 23.4) | 14.1 (10.5, 18.8) | 15.5 (10.7, 85.6) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophil | 4.3 (3.3, 5.9) | 4.3 (3.3, 5.9) | 4.3 (3.3, 5.8) | 0.7 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.3 (3.7, 5.0) | 4.4 (3.9, 5.0) | 4.1 (3.5, 4.8) | <0.001 |

| Alkaline phosphatase ( | 82.0 (67.5, 132.4) | 72.2 (60.9, 82.3) | 127.3 (81.8, 297.4) | <0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.7) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.6) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.7) | 0.048 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.3) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) | 0.2 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.6 (2.0, 3.1) | 2.7 (2.2, 3.2) | 2.3 (1.8, 3.0) | <0.001 |

| CA19-9 (U/ml) | 19.0 (6.8, 435.7) | 7.7 (4.8, 12.8) | 436.3 (84.0, 1,000.0) | <0.001 |

| CEA (U/ml) | 2.5 (1.3, 5.2) | 1.5 (0.8, 2.3) | 5.2 (2.9, 11.8) | <0.001 |

| Logistic regression with backward elimination | Support vector machine | ||||

| Predictors | P-value | AIC | Predictors | Feature weight | Importance Rank |

| Variables deleted from the model | Variables kept | ||||

| Alcohol | 0.918 | -1.99 | CA19-9 | 3.56 | 1 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 0.975 | -3.95 | Carcinoembryonic antigen | 3.12 | 2 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.989 | -5.88 | Alkaline phosphatase | 2.23 | 3 |

| White blood cell | 0.994 | -7.78 | Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio | 0.59 | 4 |

| Platelet | 0.994 | -9.56 | Haemoglobin A1c | 0.37 | 5 |

| Direct bilirubin | 0.989 | -11.09 | Variables discarded | ||

| C-reactive protein | 0.986 | -12.61 | Direct bilirubin | 0.33 | 6 |

| Hypertension | 0.978 | -13.92 | Smoking | 0.33 | 7 |

| Lymphocyte | 0.957 | -14.83 | Age | 0.2 | 8 |

| Triglyceride | 0.914 | -15.37 | Haemoglobin | 0.17 | 9 |

| High density lipoprotein | 0.860 | -15.81 | Low density lipoprotein | 0.16 | 10 |

| Gender | 0.767 | -15.77 | BMI | 0.14 | 11 |

| Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio | 0.664 | -15.63 | High density lipoprotein | 0.14 | 12 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.528 | -15.02 | Alcohol | 0.1 | 13 |

| Low density lipoprotein | 0.324 | -13.09 | Hypertension | 0.1 | 14 |

| Age | 0.109 | -8.84 | Coronary artery disease | 0.1 | 15 |

| Smoking | 0.0238 | -3.63 | Platelet | 0.09 | 16 |

| Variables kept | Gender | 0.09 | 17 | ||

| BMI | White blood cell | 0.08 | 18 | ||

| Haemoglobin A1c | Lymphocyte | 0.08 | 19 | ||

| Alkaline phosphatase | C-reactive protein | 0.08 | 20 | ||

| CA19-9 | Diabetes Mellitus | 0.04 | 21 | ||

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | Triglyceride | 0.01 | 22 | ||

| Variable | aOR (95% CI) | P-value |

| BMI | 0.88 (0.81,0.97) | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin A1c | 1.28 (1.08,1.52) | <0.001 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 1.02 (1.01,1.03) | <0.001 |

| CA19-9 | 1.01 (1.01,1.01) | <0.001 |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen | 1.41 (1.2,1.66) | <0.001 |

| BMI | Points | Hb1Ac | Points | ALP | Points | CA19-9 | Points | CEA | Points |

| 12 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 200 | 1 | 500 | 1 | 100 | 10 |

| 16 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 400 | 2 | 1000 | 2 | 200 | 20 |

| 18 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 600 | 4 | 1500 | 4 | 300 | 30 |

| 20 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 800 | 5 | 2000 | 5 | 400 | 40 |

| 22 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 1000 | 6 | 2500 | 6 | 500 | 50 |

| 24 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 1200 | 7 | 3000 | 7 | 600 | 60 |

| 26 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 1400 | 9 | 3500 | 8 | 700 | 70 |

| 28 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 1600 | 10 | 4000 | 9 | 800 | 80 |

| 30 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 1800 | 11 | 4500 | 11 | 900 | 90 |

| 32 | 0 | 14 | 1 | 2000 | 12 | 5000 | 12 | 1000 | 100 |

| 34 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 5500 | 13 | ||||

| 36 | 0 | 16 | 1 | ||||||

| 17 | 1 | ||||||||

| Points per unit of linear predictor: 0.264601 | |||||||||

| Linear predictor units per point: 3.779275 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).