Submitted:

28 March 2024

Posted:

29 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings:

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Data Extraction

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Machine Learning Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Characteristics of all Patients Undergoing Endoscopic Intervention

3.3. Variceal Band Ligation

3.4. Adrenaline Injection

3.5. Coaptive Coagulation

3.6. Hemoclip Application

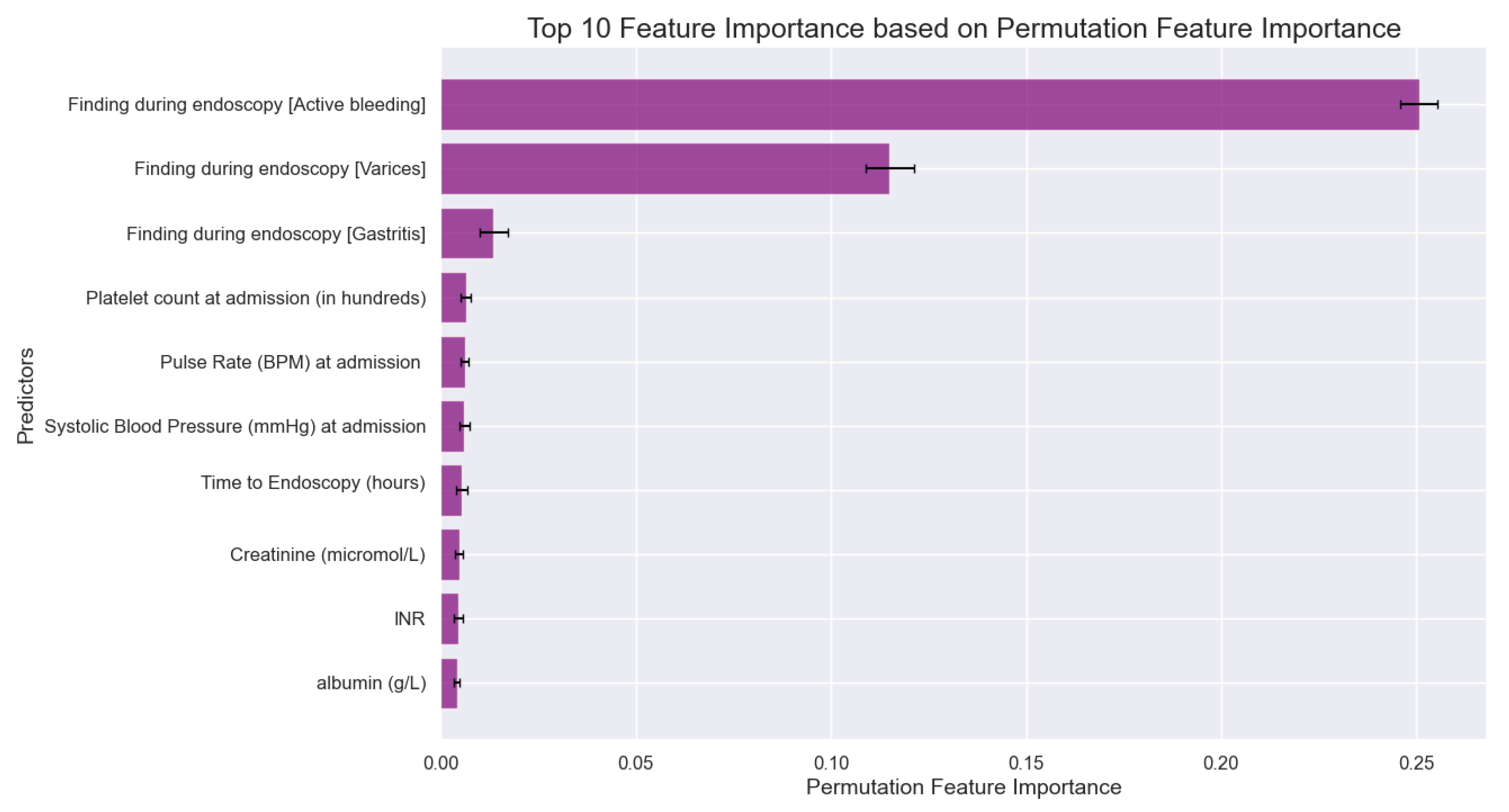

3.7. Machine Learning Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Authors’ contribution

Funding

Consent for publication

Informed Consent Statement

Availability of data and materials

Competing interests

Ethics approval and consent to participate

References

- Shung, D.L.; Au, B.; Taylor, R.A.; Tay, J.K.; Laursen, S.B.; Stanley, A.J.; Dalton, H.R.; Ngu, J.; Schultz, M.; Laine, L. Validation of a Machine Learning Model That Outperforms Clinical Risk Scoring Systems for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laine, L.; Yang, H.; Chang, S.-C.; Datto, C. Trends for Incidence of Hospitalization and Death Due to GI Complications in the United States From 2001 to 2009. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 107, 1190–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakland, K. Changing epidemiology and etiology of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2019, 42-43, 101610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hearnshaw, S.A.; Logan, R.F.A.; Lowe, D.; Travis, S.P.L.; Murphy, M.F.; Palmer, K.R. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut 2011, 60, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuerth, B.A.; Rockey, D.C. Changing Epidemiology of Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage in the Last Decade: A Nationwide Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 63, 1286–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkun, A.N.; Almadi, M.; Kuipers, E.J.; Laine, L.; Sung, J.; Tse, F.; Leontiadis, G.I.; Abraham, N.S.; Calvet, X.; Chan, F.K.; et al. Management of Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Guideline Recommendations From the International Consensus Group. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karstensen, J.G.; Ebigbo, A.; Bhat, P.; Dinis-Ribeiro, M.; Gralnek, I.; Guy, C.; Le Moine, O.; Vilmann, P.; Antonelli, G.; Ijoma, U.; et al. Endoscopic treatment of variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Cascade Guideline. Endosc. Int. Open 2020, 08, E990–E997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralnek, I.M.; Stanley, A.J.; Morris, A.J.; Camus, M.; Lau, J.; Lanas, A.; Laursen, S.B.; Radaelli, F.; Papanikolaou, I.S.; Gonçalves, T.C.; et al. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (NVUGIH): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline – Update 2021. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 300–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatchford, O.; Murray, W.R.; Blatchford, M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 2000, 356. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, A.J.; Laine, L.; Dalton, H.R.; Ngu, J.H.; Schultz, M.; Abazi, R.; Zakko, L.; Thornton, S.; Wilkinson, K.; Khor, C.J.L.; et al. Comparison of risk scoring systems for patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: international multicentre prospective study. BMJ 2017, 356, i6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Rockall, T.; Logan, R.F.; Devlin, H.B.; Northfield, T.C. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut 1996, 38, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockall, T.; Devlin, H.; Logan, R.; Northfield, T. Selection of patients for early discharge or outpatient care after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet 1996, 347, 1138–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, S.H.; Ching, J.Y.; Lau, J.Y.; Sung, J.J.; Graham, D.Y.; Chan, F.K. Comparing the Blatchford and pre-endoscopic Rockall score in predicting the need for endoscopic therapy in patients with upper GI hemorrhage. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010, 71, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veisman, I.; Oppenheim, A.; Maman, R.; Kofman, N.; Edri, I.; Dar, L.; Klang, E.; Sina, S.; Gabriely, D.; Levy, I.; et al. A Novel Prediction Tool for Endoscopic Intervention in Patients with Acute Upper Gastro-Intestinal Bleeding. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hreinsson, J.P.; Kalaitzakis, E.; Gudmundsson, S.; Björnsson, E.S. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: incidence, etiology and outcomes in a population-based setting. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 48, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssouf, B.M.; Alfalati, B.H.; Alqthmi, R.; Alqthmi, R.; Alsehly, L.M. Causes of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Among Pilgrims During the Hajj Period in the Islamic Years 1437-1439 (2016-2018). Cureus 2020, 12, e10873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamboj, A.K.; Hoversten, P.; Leggett, C.L. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Etiologies and Management. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, A.; Kaeley, N.; Prasad, H.; Patnaik, I.; Bahurupi, Y.; Joshi, S.; Shukla, K.; Galagali, S.; Patel, S. Prospective observational study on clinical and epidemiological profile of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with suspected upper gastrointestinal bleed. BMC Emerg. Med. 2023, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocic, M.; Rasic, P.; Marusic, V.; Prokic, D.; Savic, D.; Milickovic, M.; Kitic, I.; Mijovic, T.; Sarajlija, A. Age-specific causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in children. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 6095–6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakuş. ; Kara, U.; Tasçi, C.; Eryilmaz, M. Upper gastrointestinal system bleedings in COVID-19 patients: risk factors and management / A retrospective Cohort Study. Turk. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2021, 28, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenhüner, K.; Blaser, J.; Nowak, A.; Cheetham, M.; Mueller, B.U.; Battegay, E.; Beeler, P.E. Comorbidities Associated with Worse Outcomes Among Inpatients Admitted for Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 67, 3938–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moledina, S.M.; Komba, E. Risk factors for mortality among patients admitted with upper gastrointestinal bleeding at a tertiary hospital: a prospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, A.J.; Laine, L. Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ 2019, 364, l536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafa, E.F.; Mohammad, A.N. Incidence and predictors of rebleeding after band ligation of oesophageal varices. Arab. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 15, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, N.; Abbasi, A.; Khan, M.A.; Butt, S.; Ahmad, S.M. Esophageal Variceal Band Ligation Interval and Number Required for the Obliteration of Varices: A Multi-center Study from Karachi, Pakistan. Cureus 2019, 11, e4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, A.; Ahn, H.; Halwan, B.; Kalmin, B.; Artifon, E.L.; Barkun, A.; Lagoudakis, M.G.; Kumar, A. A decision support system to facilitate management of patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Artif. Intell. Med. 2008, 42, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | All patients (n=1372) | Underwent endoscopic intervention (n=242) | P value | Variceal band ligation (n=112) | P value | Adrenaline injection (n=87) | P value | Coaptive coagulation (n=54) | P value | Hemoclip application (n=19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital, n (%) | 0.004* | 0.028* | 0.57 | <.001* | 0.16 | ||||||

| KAUH | 989 (72.1) | 165 (68.2) | 76 (67.9) | 67 (77.0) | 35 (64.8) | 10 (52.6) | |||||

| JUH | 253 (18.4) | 61 (25.2) | 30 (26.8) | 13 (14.9) | 19 (35.2) | 6 (31.6) | |||||

| PHH | 130 (9.5) | 15 (6.2) | 6 (5.4) | 7 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (15.8) | |||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 56.5 (19.3) | 56.2 (16.9) | 0.816 | 51.8 (15.8) | 0.008* | 57.7 (17.3) | 0.53 | 62.5 (15.9) | 0.020* | 59.4 (15.2) | 0.504 |

| Gender (Male), n (%) | 893 (65.1) | 165 (68.5) | 0.256 | 69 (61.6) | 0.42 | 72 (82.8) | <.001* | 39 (72.2) | 0.26 | 12 (63.2) | 0.86 |

| Symptoms, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Abdominal pain | 436 (31.7) | 60 (24.9) | 0.014* | 27 (24.1) | 0.069 | 24 (27.6) | 0.39 | 15 (27.8) | 0.52 | 4 (21.1) | 0.31 |

| Heart failure presentation | 32 (2.3) | 8 (3.3) | 0.377 | 2 (1.8) | 0.69 | 2 (2.3) | 0.98 | 3 (5.6) | 0.11 | 2 (10.6) | 0.017* |

| Dizziness | 381 (25.5) | 84 (34.9) | 0.009* | 29 (25.9) | 0.64 | 39 (44.8) | <.001* | 19 (35.2) | 0.21 | 9 (47.4) | 0.055 |

| Melena | 1022 (74.5) | 166 (68.9) | 0.034* | 55 (49.1) | <.001* | 76 (87.4) | 0.004* | 47 (87.0) | 0.031* | 16 (84.2) | 0.33 |

| Hepatic disease presentation | 110 (8.0) | 39 (16.2) | <.001* | 34 (30.4) | <.001* | 4 (4.6) | 0.22 | 2 (3.7) | 0.23 | 0 (0.0) | 0.2 |

| Syncope | 36 (2.6) | 5 (2.1) | 0.715 | 0 (0.0) | 0.07 | 5 (5.7) | 0.06 | 2 (3.7) | 0.61 | 0 (0.0) | 0.47 |

| Dyspnea | 157 (11.4) | 24 (10.0) | 0.493 | 7 (6.3) | 0.072 | 11 (12.6) | 0.72 | 8 (14.8) | 0.43 | 4 (21.1) | 0.19 |

| Hematemesis | 261 (19.0) | 78 (32.4) | <.001* | 45 (40.2) | <.001* | 26 (29.9) | 0.008* | 10 (18.5) | 0.92 | 6 (31.6) | 0.16 |

| Hematochezia | 122 (8.9) | 16 (6.6) | 0.219 | 8 (7.1) | 0.5 | 7 (8.0) | 0.77 | 2 (3.7) | 0.17 | 2 (10.5) | 0.8 |

| Coffee ground vomit | 218 (15.9) | 44 (18.3) | 0.312 | 17 (15.2) | 0.83 | 24 (27.6) | 0.002* | 8 (14.8) | 0.83 | 6 (31.6) | 0.06 |

| Social history, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Smoking | 308 (22.4) | 58 (24.1) | 0.563 | 22 (19.6) | <.001* | 27 (31.0) | 0.2 | 11 (20.4) | 0.71 | 5 (26.3) | <.001* |

| Alcohol | 17 (1.2) | 8 (3.3) | 0.002* | 6 (5.4) | 0.46 | 1 (1.1) | 0.63 | 1 (1.9) | 1.00 | 0 (0.0) | 0.37 |

| Variables | All patients (n=1372) | Underwent endoscopic intervention (n=242) | P value | Variceal band ligation (n=112) | P value | Adrenaline injection (n=87) | P value | Coaptive coagulation (n=54) | P value | Hemoclip application (n=19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Hypertension | 666 (48.5) | 131 (54.4) | 0.055 | 50 (44.6) | 0.39 | 52 (59.8) | <.001* | 38 (70.4) | 0.001* | 12 (63.2) | <.001* |

| DM | 536 (39.1) | 113 (46.9) | 0.008* | 60 (53.6) | 0.001* | 38 (43.7) | 0.03* | 24 (44.4) | 0.41 | 7 (36.9) | 0.03* |

| IHD | 282 (20.6) | 41 (17.0) | 0.158 | 10 (8.9) | 0.002* | 15 (17.2) | 0.36 | 16 (29.6) | 0.092 | 6 (31.6) | 0.84 |

| CVD | 103 (7.5) | 12 (5.0) | 0.132 | 0 (0.0) | 0.002* | 0 (0.0) | 0.43 | 7 (13.0) | 0.12 | 3 (15.8) | 0.23 |

| Arrhythmias | 86 (6.2) | 12 (5.0) | 0.446 | 0 (0.0) | 0.004* | 5 (5.7) | 0.84 | 7 (13.0) | 0.038* | 2 (10.5) | 0.17 |

| CHF | 95 (6.9) | 14 (5.8) | 0.541 | 1 (0.9) | 0.009* | 8 (9.2) | 0.84 | 4 (7.4) | 0.89 | 4 (21.1) | 0.44 |

| VHD | 25 (1.8) | 4 (1.7) | 1.00 | 0 (0.0) | 0.13 | 2 (2.3) | 0.39 | 2 (3.7) | 0.29 | 0 (0.0) | 0.015* |

| Asthma | 28 (2.0) | 5 (2.1) | 1.00 | 2 (1.8) | 0.84 | 2 (2.3) | 0.73 | 1 (1.9) | 0.92 | 1 (5.3) | 0.55 |

| COPD | 15 (1.1) | 4 (1.7) | 0.555 | 0 (0.0) | 0.25 | 4 (4.6) | 0.86 | 1 (1.9) | 0.58 | 0 (0.0) | 0.32 |

| DVT | 17 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) | 0.341 | 0 (0.0) | 0.22 | 0 (0.0) | 0.001* | 1 (1.9) | 0.68 | 0 (0.0) | 0.64 |

| PE | 6 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1.00 | 1 (0.9) | 0.45 | 0 (0.0) | 0.28 | 0 (0.0) | 0.62 | 0 (0.0) | 0.62 |

| Cirrhosis | 186 (13.6) | 88 (36.5) | <.001* | 79 (70.5) | <.001* | 8 (9.2) | 0.52 | 5 (9.3) | 0.35 | 0 (0.0) | 0.77 |

| CKD | 122 (8.9) | 19 (7.9) | 0.631 | 4 (3.6) | 0.039* | 9 (10.3) | 0.22 | 5 (9.3) | 0.58 | 7 (36.9) | 0.082 |

| Malignancy | 117 (8.5) | 22 (9.1) | 0.801 | 8 (7.1) | 0.58 | 10 (11.5) | 0.62 | 5 (9.3) | 0.84 | 2 (10.5) | <.001* |

| PUD | 78 (5.7) | 15 (6.2) | 0.807 | 2 (1.8) | 0.063 | 11 (12.6) | 0.31 | 5 (9.3) | 0.25 | 0 (0.0) | 0.75 |

| None | 79 (5.8) | 8 (3.3) | 0.102 | 2 (1.8) | 0.06 | 4 (4.6) | 0.004* | 3 (5.6) | 0.95 | 2 (10.5) | 0.28 |

| Drug history, n (%) | |||||||||||

| NSAIDs | 112 (8.2) | 15 (6.2) | 0.28 | 2 (1.8) | 0.01* | 11 (12.6) | 0.11 | 5 (9.3) | 0.76 | 3 (15.8) | 0.22 |

| Aspirin | 409 (29.9) | 59 (24.5) | 0.057 | 13 (11.6) | <.001* | 29 (33.3) | 0.46 | 20 (37.0) | 0.24 | 11 (57.9) | 0.007* |

| Warfarin | 90 (6.6) | 10 (4.1) | 0.128 | 1 (0.9) | 0.011* | 2 (2.3) | 0.097 | 5 (9.3) | 0.41 | 3 (15.8) | 0.1 |

| Antiplatelets | 125 (9.1) | 16 (6.6) | 0.179 | 3 (2.7) | 0.014* | 8 (9.2) | 0.98 | 6 (11.1) | 0.6 | 2 (10.5) | 0.98 |

| DOAC | 40 (2.9) | 5 (2.1) | 0.52 | 1 (0.9) | 0.18 | 2 (2.3) | 0.72 | 2 (3.7) | 0.73 | 0 (0.0) | 0.72 |

| Heparin | 31 (2.3) | 10 (4.1) | 0.053 | 1 (0.9) | 0.31 | 7 (8.0) | 0.47 | 2 (3.7) | 0.47 | 2 (10.5) | 0.47 |

| Variables | All patients (n=1372) | Underwent endoscopic intervention (n=242) | P value | Variceal band ligation (n=112) | P value | Adrenaline injection (n=87) | P value | Coaptive coagulation (n=54) | P value | Hemoclip application (n=19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management prior to endoscopy, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Erythromycin | 9 (0.66) | 6 (2.5) | <.001* | 6 (5.4) | <.001* | 0 (0.0) | 0.43 | 0 (0.0) | 0.54 | 0 (0.0) | 0.72 |

| IV fluids | 621 (45.3) | 133 (55.0) | <.001* | 58 (51.8) | 0.15 | 50 (57.5) | 0.018* | 30 (55.6) | 0.12 | 13 (68.4) | 0.041* |

| Vitamin K | 19 (1.4) | 5 (2.2) | 0.313 | 4 (3.6) | 0.039* | 0 (0.0) | 0.25 | 0 (0.0) | 0.37 | 1 (5.3) | 0.15 |

| Plasma clotting factor transfusion | 26 (1.9) | 8 (3.3) | 0.074 | 4 (3.6) | 0.17 | 2 (2.3) | 0.78 | 1 (1.9) | 0.98 | 2 (10.5) | 0.006* |

| Tranexamic acid | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0.886 | 0 (0.0) | 0.5 | 0 (0.0) | 0.56 | 1 (1.9) | 0.064 | 0 (0.0) | 0.79 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 553 (40.3) | 112 (46.3) | 0.032* | 50 (44.6) | 0.33 | 37 (42.5) | 0.66 | 29 (53.7) | 0.041* | 10 (52.6) | 0.27 |

| Octreotide | 59 (4.3) | 29 (12.0) | <.001* | 22 (19.6) | <.001* | 5 (5.7) | 0.49 | 4 (7.4) | 0.25 | 0 (0.0) | 0.35 |

| Transfusion, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Whole Blood | 548 (39.9) | 116 (47.9) | 0.015* | 49 (43.8) | 0.665 | 47 (54.0) | 0.021* | 22 (40.7) | 0.973 | 14 (73.7) | 0.010* |

| FFP | 115 (8.4) | 33 (13.6) | 0.004* | 94 (83.9) | <.001* | 9 (10.3) | 0.767 | 3 (5.6) | 0.730 | 5 (26.3) | 0.018* |

| PRBC | 525 (38.3) | 113 (46.7) | 0.007* | 47 (42.0) | 0.600 | 47 (54.0) | 0.007* | 21 (38.9) | 0.918 | 14 (73.7) | 0.006* |

| Cryoprecipitate | 7 (0.5) | 2 (0.8) | 0.670 | 2 (1.8) | 0.136 | 0 (0.0) | 0.762 | 0 (0.0) | 0.848 | 0 (0.0) | 0.945 |

| Platelets | 11 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 0.817 | 1 (0.9) | 0.970 | 0 (0.0) | 0.975 | 0 (0.0) | 0.993 | 1 (5.3) | 0.190 |

| Pre-endoscopic scores, mean (SD) | |||||||||||

| GBS | 10.9 (2.6) | 11.4 (2.7) | <.001* | 11.3 (2.6) | 0.098 | 11.8 (3.0) | <.001* | 11.2 (2.7) | 0.301 | 11.8 (3.3) | 0.122 |

| Rockall score | 4.2 (1.5) | 4.7 (1.6) | <.001* | 4.9 (1.0) | <.001* | 4.3 (1.4) | 0.432 | 4.5 (1.4) | 0.119 | 4.6 (1.4) | 0.211 |

| Findings during endoscopy, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Active bleeding | 188 (13.7) | 136 (56.2) | <.001* | 42 (37.5) | <.001* | 69 (79.3) | <.001* | 38 (70.4) | <.001* | 10 (52.6) | <.001* |

| Esophageal ulcer | 41 (3.0) | 5 (2.1) | 0.359 | 2 (1.8) | 0.43 | 0 (0.0) | 0.091 | 1 (1.9) | 0.62 | 2 (10.5) | 0.052 |

| Gastric ulcer | 154 (11.2) | 26 (10.7) | 0.813 | 2 (1.8) | <.001* | 13 (14.9) | 0.26 | 8 (14.8) | 0.39 | 7 (36.8) | <.001* |

| Duodenal Ulcer | 314 (22.9) | 60 (24.8) | 0.413 | 3 (2.7) | <.001* | 51 (58.6) | <.001* | 15 (27.8) | 0.38 | 8 (42.1) | 0.045* |

| Varices | 239 (17.4) | 121 (50.0) | <.001* | 0 (0.0) | <.001* | 9 (10.3) | 0.072 | 3 (5.6) | 0.019* | 2 (10.5) | 0.42 |

| Mallory-Weiss Tear | 6 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.257 | 0 (0.0) | 0.46 | 0 (0.0) | 0.52 | 0 (0.0) | 0.62 | 0 (0.0) | 0.77 |

| Esophagitis | 164 (12.0) | 11 (4.5) | <.001* | 0 (0.0) | <.001* | 7 (8.0) | 0.25 | 6 (11.1) | 0.85 | 1 (5.3) | 0.37 |

| Gastritis | 281 (20.5) | 14 (5.8) | <.001* | 4 (3.6) | <.001* | 6 (6.9) | 0.001* | 3 (5.6) | 0.006* | 2 (10.5) | 0.28 |

| Esophageal Tumor | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.355 | 0 (0.0) | 0.55 | 0 (0.0) | 0.6 | 0 (0.0) | 0.69 | 0 (0.0) | 0.81 |

| Gastric Tumor | 28 (2.0) | 5 (2.1) | 0.967 | 0 (0.0) | 0.11 | 3 (3.4) | 0.34 | 2 (3.7) | 0.38 | 0 (0.0) | 0.53 |

| Duodenal Tumor | 7 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 0.819 | 0 (0.0) | 0.43 | 1 (1.1) | 0.39 | 0 (0.0) | 0.59 | 0 (0.0) | 0.75 |

| Polyps | 36 (2.6) | 6 (2.5) | 0.886 | 4 (3.6) | 0.51 | 1 (1.1) | 0.37 | 1 (1.9) | 0.72 | 0 (0.0) | 0.47 |

| Adherent Clot | 38 (2.8) | 20 (8.3) | <.001* | 6 (5.4) | 0.082 | 11 (12.6) | <.001* | 4 (7.4) | 0.034* | 4 (21.1) | <.001* |

| Gastric Erosions | 201 (14.7) | 20 (8.3) | 0.002* | 7 (6.3) | 0.009* | 2 (2.3) | <.001* | 9 (16.7) | 0.67 | 2 (10.5) | 0.61 |

| Esophageal erosion | 29 (2.1) | 4 (1.7) | 0.589 | 1 (0.9) | 0.35 | 1 (1.1) | 0.52 | 1 (1.9) | 0.89 | 1 (5.3) | 0.34 |

| Duodenal erosion | 122 (8.9) | 12 (5.0) | 0.019* | 3 (2.7) | 0.016* | 7 (8.0) | 0.77 | 4 (7.4) | 0.7 | 1 (5.3) | 0.58 |

| Time to endoscopy (hours), mean (SD) | 39.0 (92.5) | 32.1 (58.3) | 0.199 | 27.7 (39.9) | 0.175 | 41.0 (82.8) | 0.835 | 43.6 (96.4) | 0.710 | 20.9 (24.6) | 0.391 |

| Variables | All patients (n=1372) | Underwent endoscopic intervention (n=242) | P value | Variceal band ligation (n=112) | P value | Adrenaline injection (n=87) | P value | Coaptive coagulation (n=54) | P value | Hemoclip application (n=19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lab values and vitals, mean (SD) | |||||||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 121.8 (20.5) | 119.8 (20.9) | 0.131 | 116.5 (19.9) | 0.009* | 121.4 (22.0) | 0.868 | 122.7 (19.1) | 0.752 | 114.6 (25.9) | 0.135 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 72.8 (27.3) | 75.4 (57.9) | 0.115 | 70.2 (14.0) | 0.347 | 82.1 (91.9) | 0.001* | 72.3 (11.8) | 0.99 | 114.2 (193.6) | <.001* |

| MAP (mmHg) | 89.1 (21.5) | 90.4 (41.4) | 0.350 | 86.0 (15.4) | 0.144 | 95.2 (64.3) | 0.010* | 89.1 (12.9) | 0.988 | 114.0 (131) | <.001* |

| Pulse rate | 88.0 (15.7) | 88.5 (15.6) | 0.614 | 88.1 (17.0) | 0.953 | 91.0 (14.6) | 0.083 | 83.9 (13.2) | 0.076 | 89.4 (13.5) | 0.710 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.8 (3.8) | 9.3 (3.3) | 0.023* | 9.5 (4.1) | 0.348 | 9.1 (2.7) | 0.071 | 9.5 (2.8) | 0.481 | 8.7 (1.9) | 0.196 |

| Platelet count (in thousands) | 250.9 (133.8) | 201.1 (117.5) | <.001* | 141.0 (94.0) | <.001* | 265.8 (121.3) | 0.282 | 239.2 (103.7) | 0.514 | 203.0 (80.0) | 0.116 |

| Creatinine (mmol/L) | 118.8 (132.6) | 117.1 (118.5) | 0.829 | 99.3 (67.1) | 0.119 | 141.4 (160.4) | 0.099 | 113.7 (99.9) | 0.776 | 142.6 (146.3) | 0.430 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 38.6 (66.1) | 34.6 (65.9) | 0.654 | 29.6 (44.7) | 0.587 | 31.1 (40.7) | 0.676 | 41.5 (95.1) | 0.848 | 24.3 (24.8) | 0.564 |

| INR | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.5 (0.8) | 0.564 | 1.6 (0.6) | 0.142 | 1.4 (1.2) | 0.560 | 1.3 (0.3) | 0.275 | 1.4 (0.5) | 0.868 |

| Albumin | 3.6 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.6) | <.001* | 3.2 (0.7) | <.001* | 3.4 (0.6) | 0.035* | 3.6 (0.6) | 0.876 | 3.4 (0.6) | 0.255 |

| WBC count (in thousands) | 9.6 (5.6) | 9.0 (5.0) | 0.092 | 6.9 (3.4) | <.001* | 11.1 (5.4) | 0.007* | 9.9 (6.5) | 0.649 | 11.0 (3.7) | 0.252 |

| BUN | 33.7 (34.8) | 41.6 (48.2) | <.001* | 33.8 (32.9) | 0.981 | 49.2 (64.6) | <.001* | 46.8 (36.6) | 0.007* | 41.7 (28.9) | 0.314 |

| Post-endoscopic results, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Deceased | 85 (6.19) | 27 (11.2) | <.001* | 13 (11.6) | 0.013* | 11 (12.6) | 0.01* | 3 (5.6) | 0.842 | 1 (5.3) | 0.865 |

| Re-admission | 184 (13.4) | 48 (19.8) | 0.001* | 30 (26.8) | <.001* | 9 (10.3) | 0.386 | 8 (14.8) | 0.757 | 5 (26.3) | 0.096 |

| Surgery required | 25 (1.8) | 8 (3.3) | 0.056 | 8 (7.1) | <.001* | 1 (1.1) | 0.628 | 0 (0.0) | 0.307 | 0 (0.0) | 0.55 |

| Length of stay, mean (SD) | 5.9 (12.0) | 6.1 (8.3) | 0.787 | 5.7 (10.1) | 0.831 | 7.1 (6.6) | 0.334 | 5.87 (6.9) | 0.993 | 6.1 (5.5) | 0.951 |

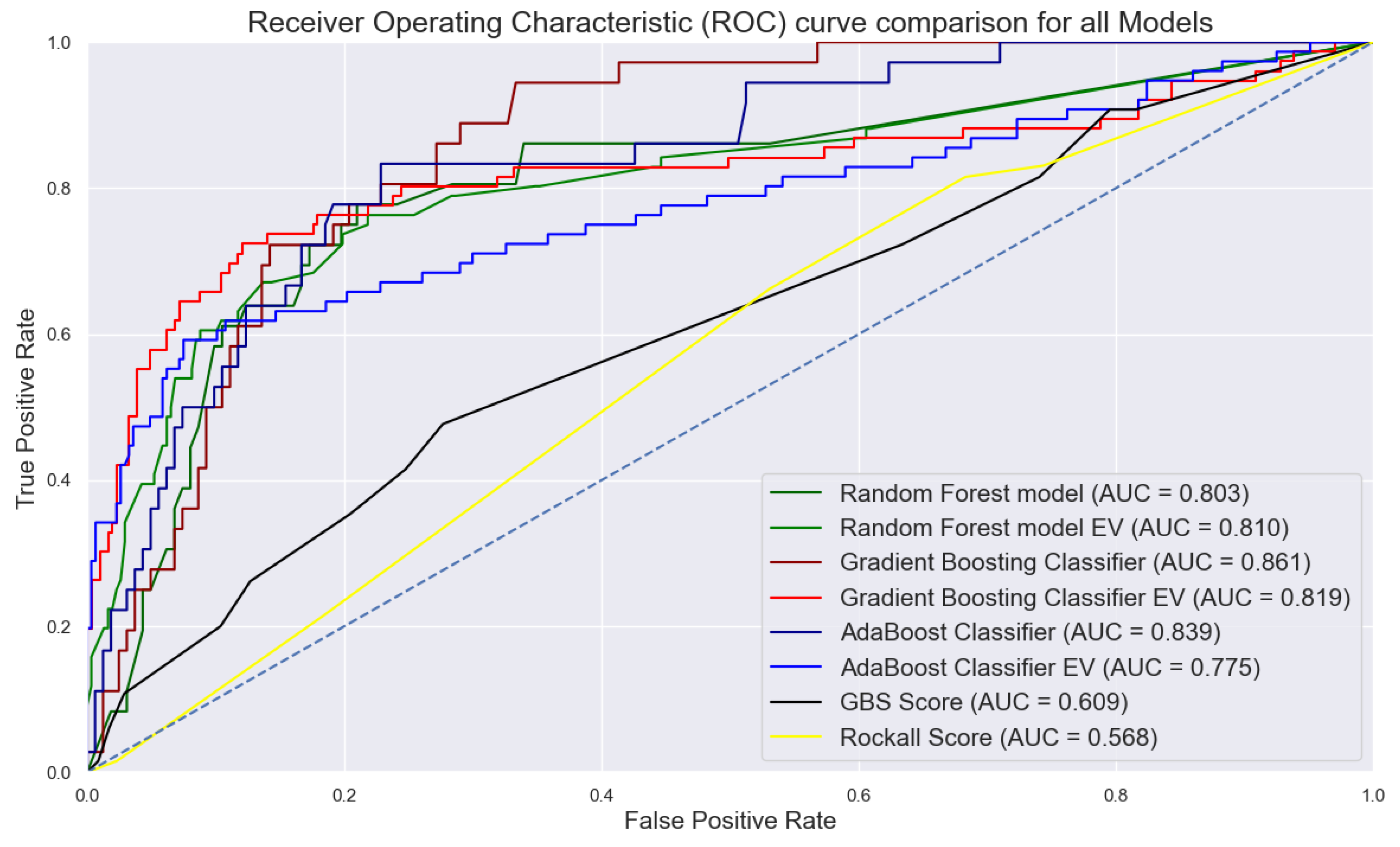

| Machine learning models | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 score | Specificity | Sensitivity | 10-fold CV | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFC | 82.32 | 51.11 | 63.89 | 56.79 | 0.870 | 0.639 | 0.931 | 0.803 |

| GBC | 82.83 | 52.17 | 66.67 | 58.54 | 0.864 | 0.667 | 0.927 | 0.861 |

| AdaBoost | 82.83 | 52.27 | 63.89 | 57.50 | 0.870 | 0.639 | 0.890 | 0.839 |

| RFC EV | 84.86 | 62.50 | 59.21 | 60.81 | 0.912 | 0.592 | 0.810 | 0.810 |

| GBC EV | 86.95 | 69.12 | 61.84 | 65.28 | 0.932 | 0.619 | 0.836 | 0.819 |

| AdaBoost EV | 84.07 | 60.00 | 59.21 | 59.60 | 0.902 | 0.592 | 0.838 | 0.775 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).