1. Introduction

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a potentially life-threatening condition. Although the overall incidence of non-variceal upper GI bleeding has decreased since the 1990s, the number of patients aged 65 and older has increased [

1]. Approximately 70% of patients presenting with GI bleeding are over 60, and the incidence rises with age. Despite advances in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, mortality remains high due to the aging population and the increased burden of comorbidities [

2].

The use of oral anticoagulants and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular events contributes significantly to the risk of ulcers and bleeding [

2,

3].

Scoring systems such as AIMS65 and Rockall have been developed to estimate the risk of mortality and rebleeding. However, there is no consensus on which scoring system is more effective. Moreover, while higher scores generally indicate increased mortality risk, specific cut-off values are not clearly defined [

4].

This study aims to evaluate mortality in geriatric patients with upper GI bleeding and comorbidities, assess the predictive value of AIMS65 and Rockall scores for mortality, and identify cut-off values for these scores. The study also investigates the role of comorbidities, anticoagulant use, and NSAID use in mortality risk.

2. Material and Method

This retrospective cohort study included 64 patients admitted with upper GI bleeding between January 2023 and June 2024. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Health Sciences University Diyarbakır Gazi Yaşargil Training and Research Hospital Hospital (02/10/2024, approval number 190).

2.1. Study Protocol

The study focused on patients over 60 with at least one comorbid disease, especially those chronically using oral anticoagulants or NSAIDs. A comparison group included patients with comorbidities but not using medications that increase bleeding risk.

All patients underwent guideline-recommended hemodynamic resuscitation, including cessation of oral intake and infusion of intravenous proton pump inhibitors. Erythrocyte transfusion was administered to maintain hemoglobin levels at 9–10 g/dL. Fresh frozen plasma was used for patients requiring more than 3 units of erythrocyte transfusion [

5].

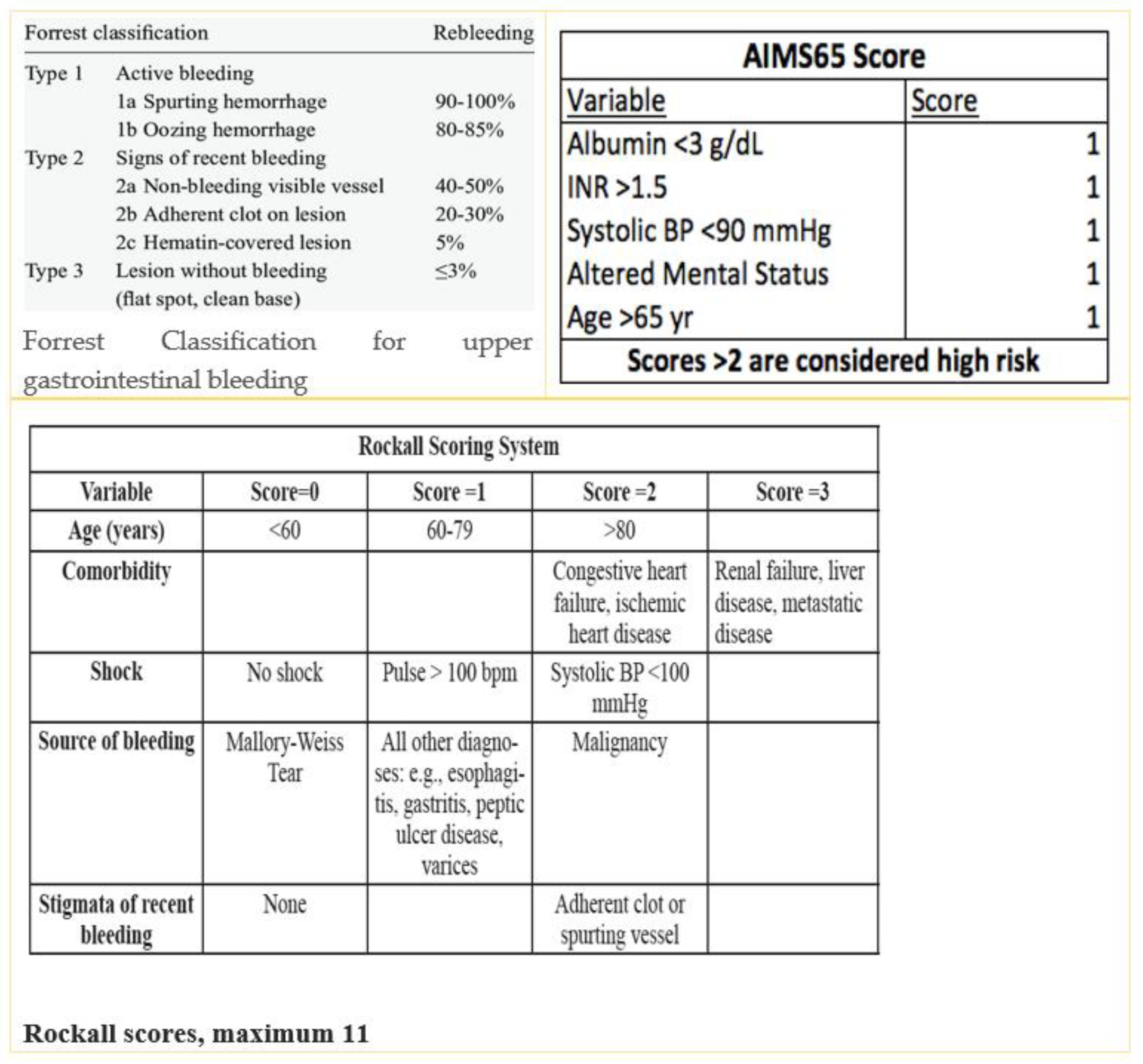

Endoscopy was performed within 6–36 hours after stabilization. Peptic ulcer bleeding was classified per the Forrest classification [

6]. Patients with high-risk ulcers (Forrest Ia, Ib, IIa, IIb) received endoscopic hemostasis [

7].

Medication use was reviewed with prescribing specialists before making decisions regarding interruption. AIMS65 and Rockall scores were calculated for all patients. The Rockall score evaluates age, vital signs, comorbidities, and bleeding cause [

8]. AIMS65 considers albumin, INR, mental status, blood pressure, and age [

9] (

Figure 1).

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Patients with variceal bleeding, malignancy-related bleeding, other etiologies, those under 60, or without comorbidities were excluded.

2.3. Patient Grouping

Patients were grouped by AIMS65 (<2 vs. ≥2) and Rockall (<6 vs. ≥6) scores. Mortality differences were analyzed. Additional grouping included patients on anticoagulants, NSAIDs, and those not on bleeding-risk medications.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

To check the normal distribution of patient data, Kolmogorov-Smirnov , Shapiro-Wilk test, coefficient of variation, skewness and kurtosis methods were used. While mean and standard deviation values were stated in continuous variables, categorical variables were expressed as n (%). Independent T test or Mann Whitney U test was used to determine the medication use rates between recovered and exitus patients and to compare AIMS65 and Rockall scores between the groups. To determine the mortality of patients according to the drugs they used, one-way ANOVA was applied to groups with homogeneous variances , and Welch ANOVA and Kruskal Wallis test were applied to groups with inhomogeneous variances. ROC analysis was performed to determine the sensitivity and specificity of Rockall and AIMS65 scores and the cut-off value. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to determine the cumulative effect of increases in both scores on mortality. All tests were two-sided and p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0 for Windows (SPSSInc.Chicago ,IL,USA) package program.

3. Results

Among the 64 patients, 50% were female; mean age was 77.6 (range 60–86). All had at least one chronic illness. The most common were hypertension (65.6%), diabetes mellitus (54.7%), chronic kidney disease (25%), and malignancy (defined as solid tumors including lung, colon, and breast cancers). A total of 78.1% had two or more comorbidities.

42.2% used no medications increasing bleeding risk; 39.1% used oral anticoagulants; 18.7% used NSAIDs. A history of hematemesis was present in 55.3%, previous GI bleeding in 33.9%, and in-hospital bleeding in 8.9%.

Forrest classification: Forrest 3 (54.7%), 2b (21.8%), 2c (9.3%), 2a (6.2%), 1b (6.2%), 1a (1.5%). All patients underwent endoscopy within a mean of 28.2 hours. Bleeding control was achieved in all. 54.7% received at least 3 units of blood (

Table 1).

Mortality rates: NSAID users 8.3%, anticoagulant users 12.0%, non-users 29.6%. Differences were not statistically significant (NSAIDs p=0.324; OACs p=0.275; non-users p=0.065).

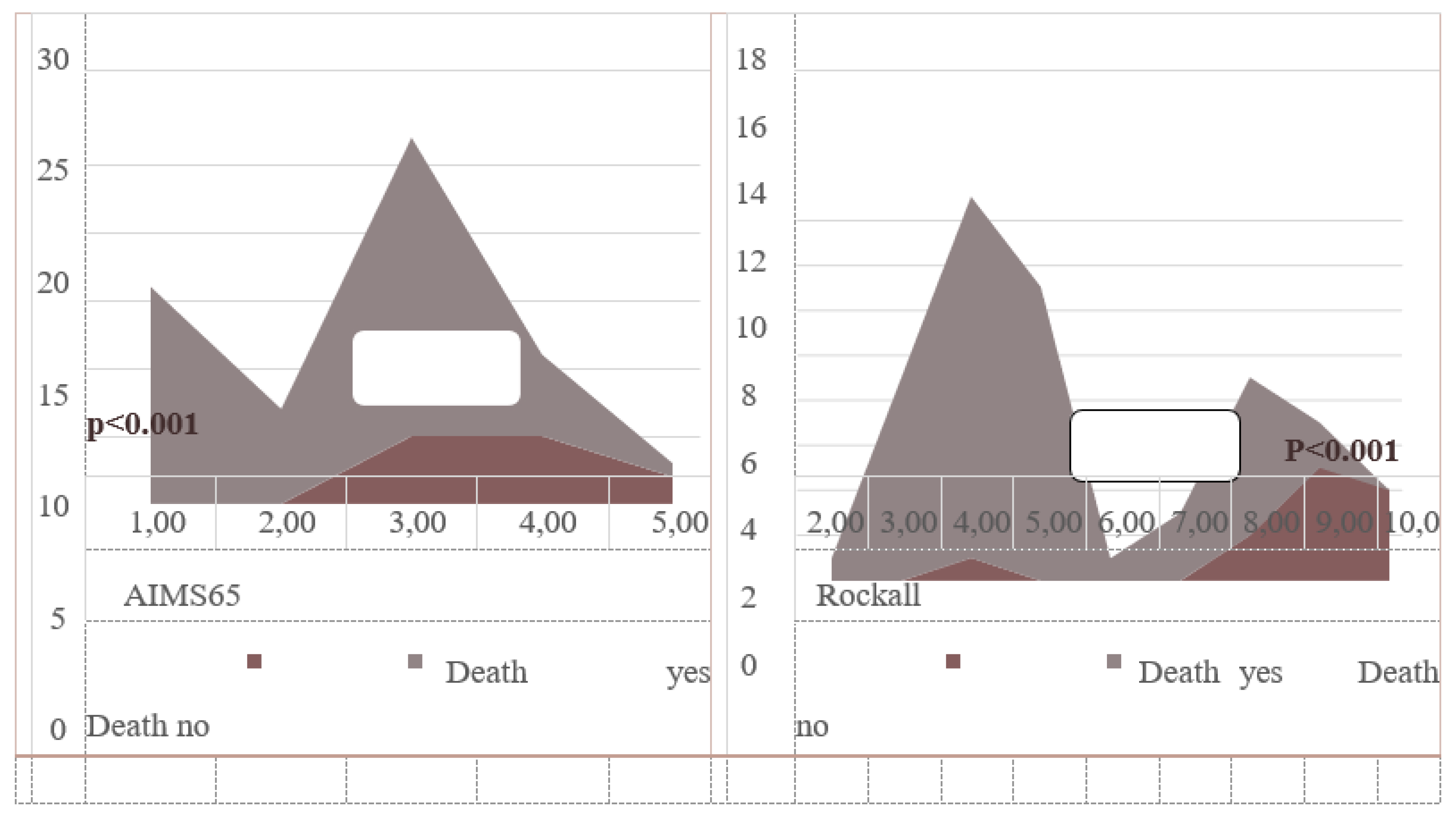

Recovered patients had lower AIMS65 scores (2.40±1.10 vs. 3.75±0.75; p<0.001). Among recovered, 25.0% had AIMS65 ≥2; among deceased, 91.6% (p=0.001). Similar findings applied to Rockall scores (4.98 vs. 8.75; p<0.001). Rockall ≥6: 26.9% in recovered vs. 83.3% in deceased (p=0.001) (

Table 2).

When patients were categorized into three groups based on medication use, no significant mortality difference was observed (p=0.157) (

Figure 2).

ROC analysis: Rockall ≥6 predicted mortality with 90.1% sensitivity and 44.2% specificity (AUC=0.920; p<0.001). AIMS65 ≥2 had 91.7% sensitivity (AUC=0.822; p<0.001). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed cumulative mortality increased with rising scores (p<0.001) (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4,

Table 2).

Most deaths occurred in patients with Forrest 3 ulcers who required minimal transfusion (1–2 units). These deaths were largely due to decompensation from underlying chronic diseases such as cardiac failure and malignancy-related complications, not active bleeding. 7.8% of patients died due to sepsis, 4.7% due to decompensated heart failure and cardiac disease, 4.7% due to malignant disease, and 1.5% due to chronic renal failure.

As a result of statistical analysis, AIMS65 and Rockall score were found to be statistically significant in predicting in-hospital mortality in our study (p<0,001). When the two scores were compared, the AIMS65 and Rockall scores were not statistically superior to each other in predicting in-hospital mortality. In addition, it was seen that both the AIMS65 and Rockall scores increased mortality in GI bleeding cumulatively (p<0.001) (

Figure 5). Mortality increased significantly as the score points increased.

4. Discussion

It is important to identify patients who may need intensive care and early endoscopic intervention for upper GI bleeding [

10]. Because a scaling system that can detect risky patients earlier and perform effective triage can contribute to reducing mortality in this patient group [11-12].

Although all patients with upper GI bleeding present to the emergency department with a common symptom such as hematemesis or melena, the clinical course and prognosis of the patients may be completely different. In this case, the algorithm or scoring system to be used should be able to distinguish between patients and determine which patients need to be hospitalized in intensive care, as well as patients who need early endoscopy. The AIMS 65 score includes parameters such as hypotension, which is an important predictor of severe bleeding, as well as age, which is an important marker that increases mortality, and albumin levels [

13], which are indicators of chronic diseases and therefore serious comorbid diseases. This shows that the AIMS65 score can be effective in identifying patients at risk at the time of first admission to the emergency department [

14].

Similarly, the Rockall score uses age and blood pressure as parameters, as does the AIMS 65 score [

15]. Although there is no albumin level in Rockall, there is a tab where chronic diseases are scored instead. Heart failure, chronic renal failure and malignancies that may directly increase the patient's mortality are scored [

16]. Both scoring systems can be used at first presentation, and each increasing score allows for early triage of patients with GI bleeding.

The in-hospital mortality rate observed in our cohort of elderly patients with upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and comorbidities was 18.7%, which is notably higher than rates typically seen in younger populations. Importantly, no deaths were directly attributed to uncontrolled hemorrhage. Instead, mortality predominantly resulted from the decompensation of underlying chronic illnesses and cardiovascular complications underscoring the complex, multifactorial nature of outcomes in this demographic. Notably, many of the deceased patients had minimal transfusion needs, further supporting a non-hemorrhagic mechanism of death.

Interestingly, the use of oral anticoagulants (OACs) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) did not demonstrate a statistically significant impact on mortality. While our findings contrast with several large-scale studies and meta-analyses that suggest [17-19] an elevated mortality risk in anticoagulated patients, these discrepancies may be explained by our relatively small sample size, early intervention strategies, or the exclusion of variceal and malignancy-related bleeding cases in our cohort.

Both the AIMS65 and Rockall scoring systems proved to be effective in predicting in-hospital mortality. Patients with an AIMS65 score ≥2 or a Rockall score ≥6 exhibited significantly higher mortality. These cut-off values correspond with those proposed in other studies [20-21] The predictive accuracy of AIMS65 may be partially attributable to its inclusion of albumin, a known independent predictor of mortality [

22]. Rockall, on the other hand, accounts for age, hemodynamic instability, and comorbidity burden, all of which are relevant in this population.

Kaplan Meier analysis showed a dramatic increase in mortality in those with a Rockall score of 8 or higher. Similarly, the same analysis showed that when the AIMS65 score exceeded 4, the increase in mortality became evident. Although previous studies did not provide clear cut-off values for these scoring systems [23-24], in our study we were able to obtain data that could suggest both basal and critical cut-off levels for both scoring systems.

Our findings align with prior literature: Hyett et al. [

25] found AIMS65 superior in predicting mortality, whereas the Glasgow-Blatchford Score (GBS) was better suited for predicting transfusion requirements. Uçmak et al. and Robertson et al. also reported that AIMS65 and Rockall were more reliable than GBS in forecasting clinical outcomes[

26,

27]. Other studies, such as those by Chang, Kim, and Jung, have found either no significant difference or variable performance depending on the patient population and endpoint[28-30].

Although our study found a slightly higher AUC for AIMS65 compared to Rockall (0.920 vs. 0.822), the difference was not statistically significant. Both scores were comparably effective overall, especially when applied in the early stages of patient evaluation.

Crucially, this study is one of the few to simultaneously assess the effects of bleeding-related medications and risk scores in a geriatric population. Our results suggest that while medication use alone may not significantly alter outcomes, the integration of structured risk stratification using AIMS65 and Rockall scores can yield more precise, individualized management strategies.

From a diagnostic standpoint, these scoring systems serve not only as prognostic tools but also as integral components of clinical decision-making. Their utility in emergency departments, particularly for identifying high-risk patients and guiding early endoscopy or ICU admission, has implications for resource allocation and workflow optimization. Furthermore, there is growing potential to embed these tools within electronic medical record systems and clinical decision support (CDS) platforms, thus enhancing diagnostic efficiency and consistency.

Emerging applications in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning could also benefit from these structured data points. Integrating AIMS65 and Rockall parameters into predictive models may support the development of real-time, algorithm-based triage systems, which are particularly valuable in high-volume or resource-limited settings.

5. Limitations

This single-center, retrospective study had a small sample size, limiting generalizability. The grouping of all comorbidities—including both low-impact (e.g., hypertension) and high-impact (e.g., malignancy, CKD)—may dilute the precision of score-specific predictions. Most patients had multiple comorbidities, but the small sample made stratified analysis difficult.

6. Conclusions

Mortality rates remain significantly high following upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, particularly in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. This study reinforces that early and accurate risk stratification plays a pivotal role in clinical outcomes, especially in this vulnerable population. Our findings indicate that the use of oral anticoagulants or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) drugs does not independently increase in-hospital mortality. This insight challenges earlier assumptions and underscores the importance of individualized risk assessment rather than blanket risk attribution to these medications. It also shifts the diagnostic emphasis from medication history alone to in-tegrated scoring and clinical evaluation.

Critically, both the AIMS65 and Rockall scoring systems emerged as powerful diagnostic tools for predicting in-hospital mortality. These scores utilize readily available clinical and laboratory data—such as albumin levels, systolic blood pressure, and comorbid burden—to deliver real-time risk assessments. In a diagnostic setting, this translates into faster triage, targeted use of intensive care resources, and more informed decisions re-garding early endoscopic intervention. Moreover, the growing interest in machine learning–based diagnostic models in gastroenterology could benefit from incorporating AIMS65 and Rockall variables as training features. This may lead to the development of more sophisticated, real-time decision algorithms that support physicians in fast-paced clinical environments.

In conclusion, this study highlights not only the prognostic value of scoring systems in managing GI bleeding but also their emerging role as diagnostic instruments that guide the clinical pathway from emergency triage to definitive care. By embedding validated risk models into diagnostic algorithms, we can significantly enhance the safety, speed, and precision of care delivered to elderly patients with upper GI bleeding.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Mortality rates according to the drugs used by patients with GI haemorrhage; Figure S2: The relationship between AIMS65 score and Rockall score and mortality in patients with GI bleeding; Figure S3: ROC analysis showing the cut-off values predicting mortality in AIMS65 and Rockall score; Figure S4: Kaplan-Meier analysis of cumulative increase in mortality as Rockall and AIMS65 scores increase; Table S1: Mortality risk of patients who recovered and death as a result of upper GI bleeding according to the drug group they used and the mean AIMS and Rockall scores.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z.A and B.E.; Methodology, M.Z.A and B.E.; Software, M.Z.A.; Validation, M.Z.A and B.E.; Formal Analysis, M.Z.A and B.E.; Investigation, M.Z.A.; Resources, M.Z.A. and B.E.; Data Curation, M.Z.A; Original Draft Preparation, M.Z.A and B.E.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.Z.A and B.E.; Visualization, M.Z.A and B.E.; Supervision, M.Z.A and B.E.; Project Administration, M.Z.A.; Funding Acquisition, M.Z.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from public, commercial, or non-profit organizations.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Health Sciences University Diyarbakır Gazi Yaşargil Training and Research Hospital (02/10/2024 date, number 190).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Thomopoulos KC, Vagenas KA, Vagianos CE, et al. Changes in aetiology and clinical outcome of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding during the last 15 years. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 16:177 -82. (PMID:15075991).

- Yadav RS, Bargujar P, Pahadiya HR, Yadav RK, Upadhyay J, Gupta A, Lakhotia M. Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Hexagenerians or Older (≥60 Years ) Versus Younger (. [CrossRef]

- Torn M, Bollen WL, van der Meer FJ, van der Wall EE, Rosendaal FR. Risks of oral anticoagulant therapy with Arch Intern med. 2005 Jul 11;165(13):1527-32. [CrossRef]

- Martínez -Cara JG, Jiménez-Rosales R, Úbeda-Muñoz M, de Hierro ML, de Teresa J, Redondo-Cerezo E. Comparison of AIMS65, Glasgow- Blatchford score, and Rockall score in Europe series of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding : performance when predicting in- hospital and delayed Mortality. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016 Jun;4(3):371-9. [CrossRef]

- Orpen-Palmer J, Stanley AJ. Update on the management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding BMJ Med. 2022 Sep 28;1(1):e000202. [CrossRef]

- Lau JYW, Yu Y, Tang RSY, Chan HCH, Yip HC, Chan SM, Luk SWY, Wong SH, Lau LHS, Lui RN, Chan TT, Mak JWY, Chan FKL, Sung JJY. Timing of Endoscopy for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 2;382(14):1299-1308. [CrossRef]

- Yen HH, Wu PY, Wu TL, Huang SP, Chen YY, Chen MF, Lin WC, Tsai CL, Lin KP. Forrest Classification for Bleeding Peptic Ulcer : A New Look at the Old Endoscopic Classification. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022 Apr 24;12(5):1066. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt MA, Peker KD, Unsal MG, Yırgın H, Kahraman İ, Alış H. The Importance of Rockall Scoring System for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Long Term Follow-Up. Indian J Surg. 2017 Jun;79(3):188-191. [CrossRef]

- Curdia Gonçalves T, Barbosa M, Xavier S, Boal Carvalho P, Magalhães J, Marinho C, Cotter J. AIMS65 score : a new prognostic tool to predict mortality in variceal bleeding Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017 Apr;52(4):469-470. [CrossRef]

- Park JH, Kim HJ, Lee DH, et al. Early Intervention Strategies in Upper GI Bleeding. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(7):1290. [CrossRef]

- Choi MK, Lee DH, Kim JH, et al. Comparative Analysis of Rockall and AIMS65 Scores in Geriatric Population. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(3):456. [CrossRef]

- Oh SY, Kim DH, Park KS, et al. Timing of Endoscopy and Mortality in Geriatric Patients. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(10):2456. [CrossRef]

- Yang MH, Kang SJ, Park JH, et al. Albumin as a Prognostic Marker in GI Bleeding. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10(7):489. [CrossRef]

- Jung KW, Kim JH, Park SJ, et al. AIMS65 Validation in Asian Elderly Population. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(4):687. [CrossRef]

- Lim JH, Cho YS, Kim JS, et al. AIMS65 vs. Rockall in Predicting Rebleeding Risk. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(6):1032. [CrossRef]

- Alamri SH, et al. Predictive accuracy of scoring systems in emergency GI bleeding. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;52:233–238.

- Popa P, Iordache S, Florescu DN, Iovanescu VF, Vieru A, Barbu V, Bezna MC, Alexandru DO, Ungureanu BS, Cazacu SM. Mortality Rate in Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Associated with Anti-Thrombotic Therapy Before and During Covid-19 Pandemic. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2022 Nov 18;15:2679-2692. [CrossRef]

- Kim TH, Lee SK, Park CH, et al. Real-Time Risk Stratification Models. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(3):514. [CrossRef]

- Lee HJ, Kim HK, Kim BS, Han KD, Park JB, Lee H, Lee SP, Kim YJ. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients on oral anticoagulant and proton pump inhibitor co-therapy. PLoS One. 2021 Jun 17;16(6):e0253310. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kılıç M, Ak R, Dalkılınç Hökenek U, Alışkan H. Use of the AIMS65 and pre-endoscopy Rockall scores in the prediction of mortality in patients with the upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2022 Dec;29(1):100-104. [CrossRef]

- . Kim JS, Park SY, Lee JH, et al. Prognostic Value of Rockall Score in Geriatrics. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10(11):911. [CrossRef]

- Kendall H, Abreu E, Cheng AL. Serum Albumin Trend Is a Predictor of Mortality in ICU Patients With Sepsis. Biological Research For nursing 2019;21(3):237-244. [CrossRef]

- Choi MK, Lee DH, Kim JH, et al. Comparative Analysis of Rockall and AIMS65 Scores in Geriatric Population. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(3):456. [CrossRef]

- Balaban DV, Pârvu M, et al. Multivariable models vs. classical scores in UGIB. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(3):505.

- Hyett BH, Abougergi MS, Charpentier JP, Kumar NL, Brozovic S, Claggett BL, et al. The AIMS65 score compared with the glasgow-blatchford score in prediction outcomes in upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 77:551 –7.

- Uçmak F, Tuncel ET. Effectiveness of Pre-Endoscopy Risk Scores in Predicting Clinical Course in PatientswithNon-VaricoseUpperGastrointestinalBleeding.Diclemedj.2024;51(1):98-105. [CrossRef]

- Robertson M, Majumdar A, Boyapati R, Chung W, Worland T, Terbah R, et al. Risk stratification in acute upper GI bleeding : Comparison of the AIMS65 score with the glasgow-blatchford and rockall Scoring systems. Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 83:1151 –60.

- Chang A, Ouejiaraphant C, Akarapatima K, Rattanasupa A, Prachayakul V. Prospective comparison of the AIMS65 score, glasgow-blatchford score, and rockall scores for predicting clinical Outcomes in patients with variceal and nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Endosc 2021; 54:211 –21.

- Kim MS, Choi J, Shin WC. AIMS65 scoring The system is comparable to Glasgow- Blatchford scores or Rockall scores for clinical prediction outcomes for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding BMC Gastroenterol. 2019 Jul 26;19(1):136. [CrossRef]

- Jung SH, Oh JH, Lee HY, Jeong JW, Go SE, You CR, Jeon EJ, Choi SW. Is the AIMS65 score useful in predicting outcomes in peptic ulcer bleeding ? World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Feb 21;20(7):1846-51. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).