1. Introduction

This paper aims to explore the multidimensional nature of space-time in psychotherapy within the theoretical framework of the analytic field (Bionian Field Theory—BFT, Ferro, 2009; Civitarese, 2022). The objective is to delineate a systematic mapping of the various space-time dimensions that emerge and interweave in the therapeutic process, analyzing their interactions with the setting and technique within different therapeutic phases.

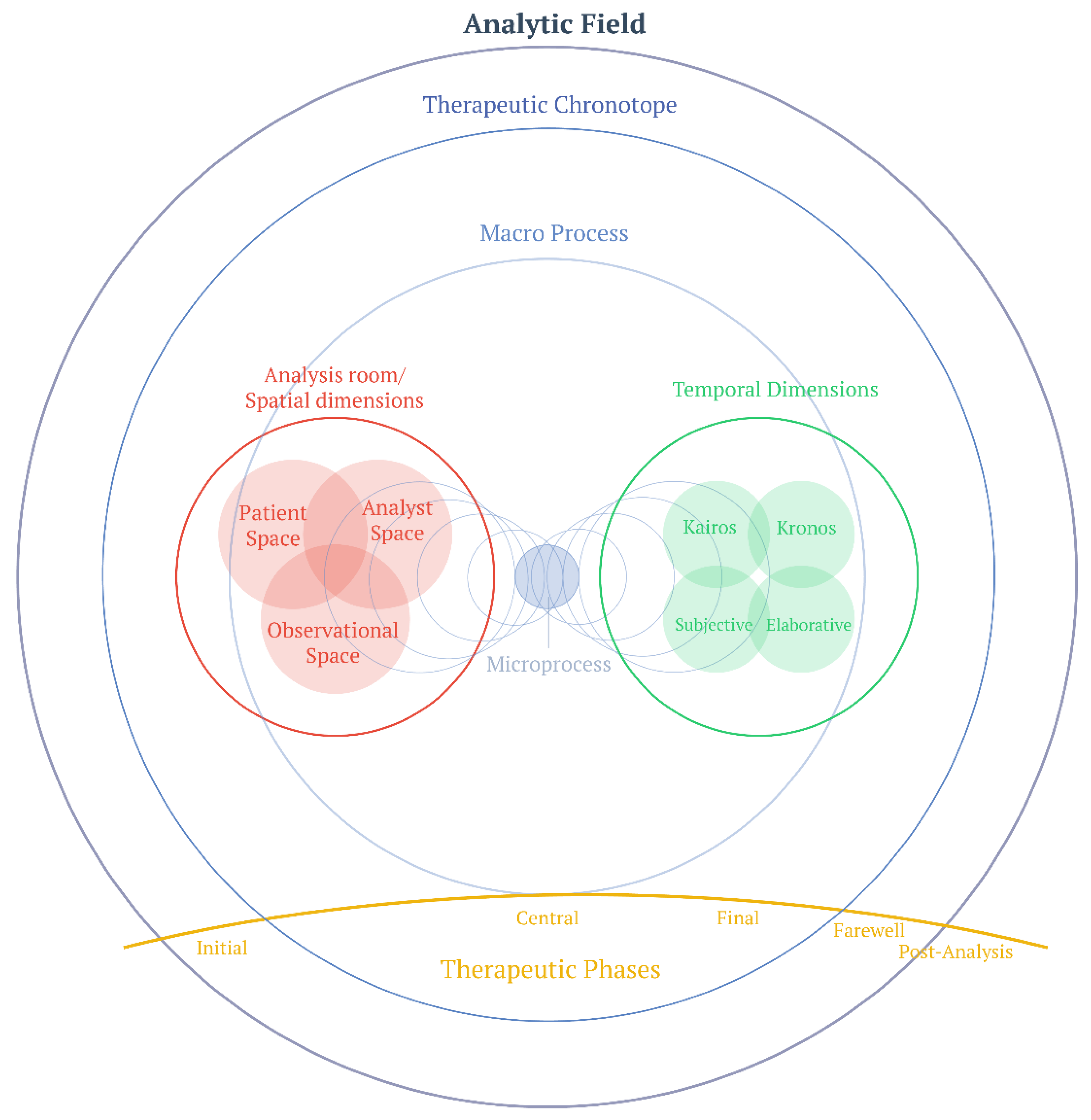

In particular, this paper introduces an original contribution: the concept of therapeutic chronotope as a meta-technical tool for understanding and managing the analytic field. This conceptualization enriches clinical practice by offering a new perspective on managing space-time dimensions in the therapeutic process.

The paper develops through six main sections: a) initially I recall the concept of analytic field, present the therapeutic chronotope and its fundamental characteristics; b) subsequently I explore the temporal multidimensionality, and then c) the spatial multidimensionality of the field; d) then I analyze the interaction between these elements in the analytic field; e) I outline the meta-technical implications of the therapeutic chronotope and its applications in clinical practice; f) I illustrate some possible future perspectives.

The methodology adopted integrates theoretical analysis of contemporary psychoanalytic literature with elements of clinical observation, focusing particularly on contributions from BFT, complexity theory, and some physical concepts useful at a metaphorical level, starting from the concept of field itself. Through this approach, an articulated framework of the space-time dimensions that characterize the analytic field emerges, revealing a complex architecture of interconnected times and spaces.

Indeed, the analytic field structures different space-times, which in turn modify the field, in a circular, reciprocal, and recursive manner. The bidirectionality of the changes that the field allows to space-times, and that they then in turn effect on the field, is fundamental.

In the therapeutic process, multiple temporal dimensions articulate themselves, manifesting on different levels. At a processual level, we observe the dynamic interaction between the macroprocess of the entire therapeutic journey, the microprocess of the single session, and the interstitial time that inhabits the spaces between sessions. Temporality also expresses itself through different qualities: the chronos of sessions interweaves with the kairos of therapeutic intervention, while the subjective times of patient and therapist dialogue with the elaborative time of psychic metabolization. This complex temporality unfolds through a circular and recursive rhythm, manifesting both synchronically and diachronically along the different phases of the process: from preliminary interviews, through initial, central, and final phases, up to post-analysis.

Parallelly, and in a way connected to time, analytic space articulates itself in multiple interconnected dimensions. The physical space of the room and formal setting frames the psychic and co-construction spaces, where the therapist’s internal space and that of the patient meet in the analytic field, creating the space of the therapeutic couple. This spatial architecture further enriches itself through the functional spaces of internal and external setting, of silences and interventions, of observation and technique, up to unfolding in the transformative spaces of containment, elaboration, transitionality, and negative capability.

The intersection and reciprocal influence of these dimensions creates what I define as a “therapeutic chronotope”, highlighting the intrinsically recursive and multidimensional nature of the therapeutic process.

The concept of chronotope, in physics, emerges from Einstein’s work (1915) on general relativity, where space and time are unified in a four-dimensional continuum, fundamentally inseparable and mutually influencing.

Bakhtin (1981) applied this concept to literature to describe how spatial and temporal dimensions are intrinsically connected in narrative, creating meaning through their unity. This theoretical foundation provides a rich metaphorical framework for understanding the therapeutic process, where space and time are not mere external coordinates, but constitutive dimensions of therapeutic experience.

Specifically, the therapeutic chronotope represents the indissoluble interconnection of space-time dimensions in the analytic field, where each configuration of the therapeutic relationship emerges as a unique event determined by the specific space-time matrix in which it manifests, including chronos time (of sessions), kairos (of the opportune moment), subjective time (of patient and therapist) and elaborative time, interwoven with the physical, psychic, and relational spaces that unfold in the therapeutic process.

It is a dynamic and multidimensional structure that allows grasping the unitary nature of the analytic experience, where space and time are not mere extrinsic coordinates, but constitutive dimensions of the very meaning of therapeutic experience, in continuous transformation through the interactions between patient, therapist, and field.

The conscious management of these space-time dimensions by the therapist emerges as a crucial element for the effectiveness of therapeutic intervention, configuring itself as an essential meta-technical tool for psychic transformation. Therefore, in this paper, beyond expositing the different space-times, I will systematically address the ways in which these influence the field, as well as the technical consequences and management of these elements and the field itself.

2. The Analytic Field

It is important to reflect on the multidimensionality of the therapeutic process, observing how all elements interweave and flow dynamically within the therapeutic couple, which within BFT is seen as a group of two within an analytic field (Ferro, Civitarese, 2015). Considering space-time in therapy implies awareness that processes are both multidimensional and recursive. The analytic field is space-time par excellence.

The idea of field is a metaphor that draws from the concept of physical field (Feynman, 1970; McMullin, 2002), and is an entity that expresses a magnitude as a function of position in space and time. As in quantum physics particles emerge from the field modifying it and being modified by it (Schroeder, 1995), so in the analytic field characters and emotional holograms emerge concerning the patient, the therapist, or their relationship (Civitarese, 2013).

The field receives and modifies itself instantaneously in toto when a change occurs within it. It allows itself to be perturbed and in turn perturbs the surrounding space. It is traversed by forces. At a psychoanalytic level, the Barangers (1990) and Corrao (1986, p. 43) worked on the conceptualization of the field, defining it as a “function whose value depends on its position in space-time: it is a system with infinite degrees of freedom, provided with infinite possible determinations that it assumes at every point in space and at every instant in time.”

The clinical dimension of therapeutic space-time manifests itself concretely through the therapist’s ability to sensitively modulate their presence and interventions. For example, in working with patients with complex trauma or borderline disorders, space-time management becomes crucial. In these cases, the therapist must be particularly attentive to the “density” of the analytic field: sometimes it is necessary to dilate psychic space to contain fragmented emotional states, other times it is necessary to restrict such space to prevent excessive dispersion of the patient’s psychic energy. The synchronization between the patient’s subjective time and the technical time of intervention becomes a fundamental therapeutic element. A too brief silence can interrupt an elaboration process just begun, while a too prolonged silence can generate anxiety and fragmentation. In clinical work, this awareness translates into a continuous re-modulation of field boundaries: the therapist becomes almost a “modulator of emotional frequencies”, capable of creating the conditions for therapeutic experience to unfold in its transformative potential. Such modulation requires deep attunement and constant reflective capacity, where listening is not only auditory but becomes a true mental setting that welcomes, metabolizes, and returns emerging emotional configurations.

3. Time and the Multidimensionality of Field and Therapy

After examining the general characteristics of the analytic field, it is fundamental to explore in detail how the temporal dimension articulates and interweaves with the spatial ones, creating that particular configuration I define as therapeutic chronotope.

We can imagine the therapeutic field as a multidimensional structure, where the three spatial dimensions (the physical room, the therapist’s psychic and psycho-physical space, the patient’s internal space) intersect with the temporal dimension, creating what we might define as a therapeutic chronotope, borrowing Bakhtin’s term.

The term, borrowed from Bakhtin’s work (1981), which he elaborated and applied to literature starting from Einstein’s theory of relativity, indicates the constitutive, dynamic, and multidimensional interconnection of space-time relations (

Figure 1).

In the psychoanalytic context, the chronotope assumes particular relevance both epistemologically and ontologically, as it represents not only a mode of understanding analytic experience but also the indissoluble unity between spatial and temporal coordinates of the field, where each relational configuration emerges as a unique and unrepeatable event, determined by the specific space-time matrix in which it manifests.

This conception allows grasping the intrinsically unitary nature of analytic experience, where space and time are not mere extrinsic coordinates, but constitutive dimensions of the very meaning of therapeutic experience, in continuous transformation through the interactions between patient, therapist, and field.

That is, space and time, or better spaces and times in therapy, are not only strictly correlated, but contribute to the attribution and construction of meaning in a couple-specific way both within the single session and throughout the entire therapeutic process.

Within the therapeutic chronotope, further temporal sub-dimensions manifest themselves (Nissen, 2023):

- -

Chronos time: the chronological time of sessions, their duration, their frequency

- -

Kairos time: the opportune moment for interpretation or therapeutic intervention

- -

The subjective time of patient and therapist: how the duration of the session and the interval between sessions is experienced

- -

Elaborative time: the process of metabolization that occurs between one session and another

In the flow of different therapeutic phases, and within the field, infinite space-times can open up, in the patient, in the therapist, and in the couple. The potential narrative, semantic, and symbolic trajectories are infinite.

For example, the patients in the here-and-now of therapy speak of the past, to re-narrate it and thus modify the future trajectory. Or, they may speak of what worries them in the future, and meanings can be found in their history. The temporal, semantic, and symbolic interweaving is continuous, weaving embroideries in the progression of sessions and dialogue.

In this regard, it is useful to introduce the concept of “fractal dimension” (Mandelbroit, 1982) of the analytic field, where each space-time potentially contains infinite other space-times, each with its own characteristics and specific dynamics. This recursive property of the field manifests particularly in the different phases of the therapeutic process.

Thus, the field is a space-time that allows the continuous emergence of spaces and times, which become inhabited by narrative, by “dreams”, and by the therapeutic couple.

For the therapist, being in the field means assuming a particular position within the couple, which is an active, participating position, not that of a mere aseptic and detached analyzer. It also means disposing oneself to grasp the deep aspects, often visual, metaphorical, dreamed elements of the narrative. That is, as Civitarese (2023) says, one must de-concretize reality and concretize the dream.

Within the field, experiences and characters will emerge, seen as emotional representations of the narrative. These are the key to understanding for the therapist, who can thus help the patient in the process of symbolopoiesis, which in turn will allow improving the mind’s capacity to think and think about itself. The analytic field is a transversal conceptualization that creates a frame of reference usable across both setting (internal and external) and theory of technique. It is allowed in each session by the analyst, and this too has a recursive character.

This multidimensional vision of space-time in therapy allows us to better understand how the therapeutic process is not linear but circular, not uniform but rhythmic, not only spatial or temporal but always space-temporal.

Now it is fundamental to consider the different phases of the therapeutic process: the preliminary encounters at the end of which the therapeutic agreement occurs, the initial phase of therapy, the central phase, the final phase, in which farewell also takes place, the final phase without sessions, and post-analysis (Kächele, Thomä, 1985; Langs, 1989).

Each of these phases represents a particular chronotope within the broader analytic field, with its specific space-time characteristics and its peculiar modes of technical intervention (McWilliams, 2004).

In each of these, the therapist’s internal setting, types of interaction with the patient, and objectives modify themselves. Very briefly, the main objectives of the initial phase, when the focus is on establishing the therapeutic alliance, are the emergence of transference, emotional convictions, observation of style and narrative contents, main defenses, symptoms, and relational modalities of the patient; furthermore, observation of the analytic third and emerging characters occurs. All this allows the formulation of diagnostic hypotheses. It is also fundamental to co-construct the therapeutic agreement and establish the formal setting, noting also how it is inhabited or acted upon, and contain the emotions that the patient brings, beginning to detoxify them.

This initial phase can be conceptualized as a period of “space-time calibration”, where therapist and patient begin to attune themselves to their respective rhythms and ways of inhabiting therapeutic space. It is a delicate moment in which the first coordinates of the analytic field are established.

In the central phase, instead, the focus is on perturbation, on change. From a technical point of view, interpretations can begin to be made, both transferential and extra-transferential, as well as of dreams. In this case, the therapeutic objectives are the introduction and activation of perturbations, as well as a new emotional relational experience. Pathogenic or dysfunctional emotional convictions must be relativized, and then it is necessary to expand them, stimulate new ones and co-construct them, through the development of multimodality (Cavicchioli, 2013).

The central phase represents the moment of maximum plasticity of the analytic field, where space-time dimensions become more fluid and malleable, allowing what we might define as a “therapeutic deformation” of the patient’s subjective space-time.

The therapist will evaluate how to dose perturbative interventions. In the case of interpretations, they will prefer weak or unsaturated ones, to allow the patient both to accept them and to add gnostic, signifying, and narrative content (Ferro, 2002; Ferro, Civitarese, 2015). Through evoked countertransference, as therapists we feel the result of projective identifications (Ogden, 2004 a). We can then elaborate it, transforming it into reflective countertransference, and use it at a therapeutic level. In this central phase, we can observe, facilitate, and return changes both within and outside the setting that will affect us, the patient, and the couple.

In the final phase, instead, the resolution of transference will occur, along with the integration and consolidation of change, and finally separation. This is what happens within the therapeutic macroprocess, which the therapist must continuously observe and keep in mind.

The final phase can be seen as a progressive “space-time reconfiguration”, where the modifications that occurred in the analytic field consolidate into new, more flexible and functional psychic structures.

Within each phase, space-time management is different. Think of pauses: a patient reveals something they had never realized before, and does so in a way that is somewhat present, somewhat absorbed. We are listening, and we make a pause, to allow breath to the word, to allow the assumption of this new awareness that has entered the therapeutic space.

From the macroprocess we now move to the microprocess. Indeed, the therapeutic macroprocess is the “large scale”, recursive vision of what happens in the microprocess.

The microprocess is everything that is contained within the single session, which will be composed of initial, central, and final moments. It is in the here-and-now of the session that the interweaving between space and time, between setting and technique, primarily unfolds. Everything will be couple-specific, strongly intersubjective. In the time of the here-and-now, space opens for the patient’s narrative, for listening, for silence, for acceptance, for opening, for questioning, for restitution, for interpretation, for perturbation, for emotional contagion, for developing and inhabiting the therapeutic relationship.

The microprocess can be conceptualized as a holographic miniature of the complete therapeutic process, where each moment potentially contains all elements of the macroprocess, in a sort of temporal fractal (Grotstein, 2007).

Beyond the macroprocess and microprocess, there is a third temporal dimension. This inhabits the time that elapses between sessions, and concerns both the patient, in their more or less conscious elaborative process, and the therapist, through the après-coup, who reviews what happened within the session, observing its microprocess and, if necessary, continuing to transform the patient’s β elements into α (Ogden, 1997; Laplanche, 2006). The time we speak of is circular, dynamic, also subjective.

This third temporal dimension could be defined as “interstitial time” or “elaborative time”, a liminal space-time in the Turnerian anthropological sense, that is, a transitory and transformative state that, in the psychoanalytic context, configures itself as a potential area of unconscious elaboration where psychic elements are no longer in their original form but have not yet reached a new stable configuration, similarly to what happens in the intermediate phase of rites of passage (Ogden, 1989; Turner, 1996; Levine et al., 2013). In this phase, the deepest transformations occur, even outside the immediate awareness of both patient and therapist.

The management of silence in therapy represents a paradigmatic example of the intersection between space and time in the analytic field. As highlighted by Reik (1948), therapeutic silence is not mere absence of sound, but an active and dynamic space-time of elaboration. Ogden (1997) conceptualizes it as a container for both patient’s and analyst’s reverie, while Green (1975) defines it as “the frame of the capacity to be alone in the presence of the other”.

In the context of the analytic field, silence can function as a powerful transformative tool through different mechanisms:

- -

As a space of containment (Bion, 1962) that allows the elaboration of beta elements

- -

As a time of psychic metabolization that facilitates the emergence of new configurations of meaning

- -

As a transitional area (Winnicott, 1971) where patient and therapist can co-construct new meanings

Think of when a patient reveals something they had never realized before, and while doing it he is somewhat present, somewhat absorbed. We are listening, and we make a pause, to allow breath to the word, to allow the assumption of this new awareness that has entered the therapeutic space. This silence contains. Or better: does this silence contain?

Silence contains meanings that are always couple-specific: for example, the space of realization, the possibility of adding more on the person’s part, the possibility of being, the possibility of contact with the self or with one’s emotions, the legitimation from our part of their experience and of what has emerged. But the containing valence of silence is not automatic. If the silence is too long for what the person can bear, or for what is adequate on our part as therapeutic stimulus, the patient might experience anxiety, feel lost, need to defend themselves, feel us as absent, project other meanings onto us. In these cases, from containing and opening space, silence becomes emptiness to be filled with something else, to soothe possible suffering (Quinodoz, 1996).

The rightness, the kairos of silence and its times, beyond being couple-specific, must also be measured with the progression of therapeutic phases. In the initial phase, we will be particularly careful in dosing them, in the central phase we can leave more space, and in the final phase even more. This interweaving between the space of silence and the space for silence creates strongly interwoven and interdependent dimensions that, like in a fractal, nourish and contain more.

4. Spaces in Times, of Times, and with Times

What spaces does all this occupy? The spaces can be more or less physical, more or less tangible and become inhabited by the therapeutic couple. First and foremost, the therapists’ internal space, their internal setting, with which they listen to and welcome what the patient brings, emotionally attuning with them. The setting can vary according to therapeutic phases, to allow first a lowering of anxiety, and then in the central phase, a change. Therefore, the therapists’ awareness of their experiences and dynamics is fundamental, in order to substantiate their role with their self-knowledge and their relational modalities. The internal setting is fundamental for the construction of the field and for the two observational registers, that of the reality level and that of the dream level. It must be simultaneously stable and flexible, constantly modulating itself based on the needs of the therapeutic process and the characteristics of the patient.

On these foundations of setting and awareness, the therapist, especially in the initial phase, constitutes and modulates the adequate and functional internal setting for the individual patient. The internal setting also varies according to therapeutic phases, creating a further interweaving between space and time, between setting and technique. The internal setting is the basis on which to build technical and therapeutic competencies. Therefore, internal setting, setting, and technique form a complementary and essential triad, on which therapy structures itself (Bleger, 1967; Bolognini, 2002).

This triad can be visualized as a three-dimensional dynamic system, where each element influences and is influenced by the other two in real time, creating what we might define as a “therapeutic attractor” in the sense of chaos theory.

As happens in Lorenz’s attractor (1963), where three interdependent variables generate a complex but recognizable pattern in phase space, so the continuous interaction between internal setting, setting, and technique produces recurring configurations that, despite their apparent chaos, tend toward preferential states characteristic of that specific analytic couple. Chaos and complex systems theory has already been applied to psychoanalysis, showing an efficacious set of tools to consider intersubjective dynamics (Lenti, 2014; 2016).

Between technique and internal setting, we find negative capability, that is, according to Bion (1960), the capacity to stay in the emotional situation, to support what is in the field, to bear those modalities, the capacity to stay there without fleeing and simultaneously without reacting. This is a very important therapeutic factor, through which we allow our mind to implement transformative processes. Negative capability is a process that is first of all affective, unconscious. Then it becomes sayable, at least internally to ourselves, and thus elaborable.

Negative capability can be conceptualized as a particular form of “curvature” of the therapist’s psychic space-time, which creates a welcoming space for the patient’s emotional contents.

Negative capability, together with alpha function and reverie (Bion, 1962; Ogden, 1997), can transform those emotional elements that the patient projects onto the therapist. At that point, the patient can re-introject something that has been modified in the intersubjective field, just like the child who assimilates the alpha function exercised by the mother. This process occurs in the therapist and in the field at a predominantly unconscious level, and is a substantial part of therapeutic work.

This transformation process can be seen as a form of “space-time metabolism”, where beta elements are processed through a series of “psychic digestions” that occur in different temporal layers of the analytic field (Ferro, Civitarese, 2015).

The therapists continuously open spaces within themselves to welcome the parts of the patient that gradually emerge. In my experience as a psychotherapist, the more severe the patient is, the more necessary it becomes to open deep spaces within myself, continuously detoxifying the powerful projective identifications that arrive. The flows of projective identification in fact substantiate the field, traverse us and in general the therapeutic relationship. Therefore, it is fundamental to understand, welcome, detoxify and elaborate them, without acting them out, as much as possible.

These internal spaces could be conceptualized as “psychic decompression chambers”, where projective identifications can be welcomed, gradually elaborated, and transformed in a safe way.

Then there is the persons’ internal space, or better the spaces that their self allows itself to take and express. The spaces of awareness, of dynamic and adaptable emotional convictions, of their change. In the intersubjective approach, the therapist has faith in the patient’s resources and in the capacity to signal different communicative positions. We can also think of the patient’s mind as a container with which we work. That is, one of the aims will be to improve the container’s capacity to think, feel, symbolize (Ferro, Civitarese, 2015). The container, clearly dynamic and doubly interfaced with the body, will modify itself throughout the therapy.

With BFT, the therapist’s main role changes, shifting from being interpretive, hermeneutic, capable of decoding latent meaning, toward a disposition to let oneself be traversed by the emotions that develop in the field starting from the patient’s utterances. This attitude generates an interpretation endowed with meaning, which will then need to be adequately dosed so that it can be received by the patient. We move from a therapist who crystallizes and photographs a projective identification to one who is able to receive the emotional wave, absorb it, digest it, and then communicate it interpretatively, if they deem it appropriate, without saturating the field too much or too often.

This theoretical evolution can be metaphorically seen as a transition from a “Newtonian” conception of therapeutic space, characterized by fixed points and defined trajectories, to a “quantum field” conception, where probabilities, state superpositions, and constructive interferences within the therapeutic field prevail.

There is also the analysis space, constituted by the actual room, the environment where everything happens. This is one of the main elements of the formal setting, consisting of the rules that the therapist establishes within what becomes the therapeutic agreement. We will activate the formal setting, making it operative.

Here too we see the interweaving between space and time because the setting creates a rhythm, a rituality. A predictability occurs that allows internalizing the time of work, relationship, and exchange. The setting is a container that—according to Bion (1962)—must have elasticity and robustness. It is thus thought, lived, acted upon, and implicit and explicit elements interweave within it. We must always maintain an observational focus on this. Ferro speaks of setting as a “precipitate of experiences” starting from Freud’s work (Freud, 1913; Ferro, 2007). If we think about it, it is also a precipitate of experiences within the analytic journey. According to Ferro, the objective is to arrive at a rigorous setting.

The physical space of the analysis room can be conceptualized as a “psychic gravitational field”, where, as happens in the gravitational field in the presence of a mass (Geroch, 1981), the presence of therapist and patient, together with their relationship, creates “curvatures” in the relational space-time, influencing how emotional contents move and transform.

The last important point concerns observation. The spaces within the field are also observational spaces. As I mentioned before, the therapist can observe both with a “concrete” and a dreaming register, stepping back and setting themselves to concretize the dream. This dual observational modality creates what we might define as a “principle of therapeutic complementarity”: the two modes of observation are complementary and necessary for a complete understanding of the field.

There are three axes of observation: the historical and “real” axis of the events (external reality), the phantasmatic axis of the patient’s functioning (internal reality), and especially the axis of relational reality that takes form and becomes vivified within the emotional field that the couple generates (Ferro, 2006; Levine, 2022). These three observation axes construct the reality of the field and continuously oscillate among themselves, giving rise to infinite openings of meaning.

These three axes could be visualized as the coordinates of a complex three-dimensional system, where each point represents a particular configuration of the analytic field at a given moment.

There is then a “meta” gaze—the meta-cognitive capacity to observe, understand, and name what happens within oneself at multiple levels, what one is doing, and how what Ogden (1994) calls the “intersubjective third” moves. We see that observation traverses the entire field, both horizontally-transversally and vertically. Clearly, according to constructivist epistemology and also intuitively, the modes of observation will modify the entire field (Maturana, Varela, 1980; von Glasersfeld, 1995). The more the therapist is aware of all these observational vertices and their contents with that specific patient, the better.

Meta-cognitive capacity can be seen as a form of “consciousness” of the therapeutic field, which allows simultaneously observing multiple dimensions of the therapeutic process without compromising its complexity.

5. Effects of Space-Times on the Analytic Field

Space-time dimensions act on the analytic field through an articulated dynamic of emergent phenomena and transformations manifesting on multiple levels. At a structural level, we observe two fundamental types of movement: vertical ones, characterized by the emergence of new psychic contents, and horizontal ones, concerning the dynamics of approach and distancing in the therapeutic relationship. These multidirectional movements give life to specific configurations—characters and emotional holograms—that inhabit and enrich the analytic space.

The transformation of the field articulates itself according to two complementary temporal modalities: the synchronic one, manifesting in the here-and-now of the session, and the diachronic one, developing through the entire therapeutic process. As in the quantum field, where particles emerge modifying the field and being simultaneously modified by it, so in the analytic field each emergent element—be it an emotion, a memory, or a new awareness—transforms the field itself while being transformed by it, in a process of continuous co-evolution (Civitarese, 2016).

This recursive dynamic presents fractal-like properties, where each moment of the process potentially contains the totality of therapeutic experience, manifesting both in the temporal dimension (between present, past, and future) and in the spatial dimension (between internal and external, between patient and therapist). As Riolo (2019, p. 23) effectively synthesized: “It is the space of analysis that transforms”, highlighting how the field itself becomes the main agent of change.

The interweaving is thus given not only by the interfacing of internal setting, setting, and technique, not only by the relationships between patient and therapist and between space and time, but also by the fact that in the field, and thanks to the field, space-time modifies its content and vice versa, in an infinity of possible trajectories. This ensemble of processes occurs both synchronically and diachronically.

Therefore, there are two modes of time “undulating”: the synchronic mode, during the session regarding contingent dialogue, and the diachronic mode, which can occur in different and complementary ways through the après-coup on the therapist’s part and reflection on the patient’s part.

In this perspective, the analytic field can be seen as a therapeutic multiverse, where multiple possibilities of development and transformation coexist, actualized through the dynamic interaction between therapist and patient.

6. Meta-Technical Implications of the Therapeutic Chronotope

The therapeutic chronotope configures itself as a meta-technical rather than technical tool: it does not prescribe specific interventions, but provides a conceptual framework through which the therapists can understand and modulate their work, organizing the therapeutic experience in an even more structured and conscious way (Ferro, 2005). This meta-technical nature manifests in the capacity to organize clinical thinking around the space-time dimensions of the field, allowing a more refined awareness of processual and transformative dynamics.

While technique deals with “how to do and why”, meta-technique, thanks to the conceptualization of the therapeutic chronotope, provides the frame of reference for understanding “when and where” to use certain techniques, allowing a finer and more conscious modulation of therapeutic intervention.

In this sense, it does not replace existing techniques, but it enriches them with a new dimension of understanding and application, providing a broader framework for orienting technical choices within the field.

Indeed, as highlighted by Ogden (2004 b), this perspective allows the therapist to develop a more refined awareness of the space-time dimensions of the analytic field, facilitating a more precise modulation of interventions and a greater capacity for holding and containing.

This awareness expresses itself primarily in managing the temporality of interventions, where the therapist must orchestrate different temporal levels: the technical timing of intervention, the patient’s subjective time, and the elaborative time necessary for psychic metabolization. This temporal orchestration is intrinsically linked to the relational dimension and to the freedom that emerges in the interpersonal field (Stern, 2015).

The modulation of psychic space represents another crucial aspect of this meta-technique. The calibration of relational distance, management of silence spaces, and creation of transitional areas for elaboration are fundamental elements for developing intersubjectivity in the therapeutic process (Mitchell, 2000). This spatial modulation constantly interweaves with the attunement of the therapist’s internal setting, which must adapt to different phases of the process while maintaining that negative capability essential for analytic work.

This meta-technical perspective allows observing the therapeutic process from a meta-level (Bromberg, 2011), facilitating the understanding of interconnections between different field dimensions and promoting transformations through conscious management of therapeutic space-time. The therapeutic chronotope thus becomes a meta-technical tool that enriches understanding and application of specific techniques, allowing a more conscious and integrated clinical practice, where the space-time dimension is no longer just the background of intervention, but becomes an integral part of the transformative process itself.

In this perspective, the therapist can use awareness of the therapeutic chronotope to more finely modulate their interventions, calibrating not only the content, but also the space-time form of therapeutic experience. This conscious modulation contributes to creating that potential space of transformation where patient and therapist can co-construct new meanings and new possibilities of being in the relationship.

This set of actions expresses itself through modulation of the internal setting, which must adapt to specific phases of the process, calibrating containment and accurately modulating intervention timing.

This, together with the ability to create and maintain differentiated psychic spaces for elaborating projective identifications, constitutes an essential prerequisite for transforming β elements into α elements.

Field management requires fine space-time coordination, conscious management of silence, and careful modulation of interpretive timing.

In particular, the therapist’s attunement with different rhythms and spaces of the process—from the kairos of interpretation to the management of interstitial time, from calibration of containment spaces to the opening of transitional areas—determines the quality of the patient’s transformative experience.

This complex architecture of technical interventions allows the therapist to support and facilitate transformations occurring in the analytic field, maintaining that flexibility and depth necessary to welcome and promote therapeutic change.

Meta-processual awareness of these dimensions further allows the therapist to modulate technical interventions more precisely and sensitively to the specificities of the analytic field that develops with each individual patient, thus increasing the probability of positive therapeutic outcomes.

7. Future Perspectives

This conceptualization of the therapeutic chronotope as a tool for meaning construction and meta-technique opens new perspectives for both theoretical and clinical research. The construct’s applicability in different treatment modalities represents a promising area of investigation, together with the development of methodologies for evaluating and refining the therapist’s space-time awareness in the analytic field. A further area of exploration concerns the integration of this approach with other conceptualizations of the analytic field, particularly with post-Bionian and intersubjective models. Future research can also focus on systematic study of the relationship between conscious management of space-time dimensions and therapeutic effectiveness, contributing to empirical validation of this meta-technical approach.

The therapeutic chronotope thus configures itself not only as a conceptual tool for understanding the analytic process, but also as a starting point for new explorations in the field of psychoanalytic psychotherapy, promoting constructive dialogue between theory, technique, research, and clinical practice.

8. Conclusions

Through systematic illustration I have shown the different times and spaces of therapy, their interweaving, and their interactions with the analytic field, setting and technique. All this is connected to recursivity, multimodality, and multidimensionality of psychotherapeutic treatment. It is fundamental to represent these aspects to understand the depth of the psychotherapist’s work, which affects not only the patient’s mind, but also our own, their body and our body, their system and our system. In some cases, psychoanalysis itself. The theory of the analytic field, the paradigm of complexity, the metaphors borrowed by the physical language, and constructivist epistemology, through their transversality, allow identification of all these elements and promote our awareness as therapists.

It is clear that the field is a multidimensional and recursive system of systems, space-time of space-times that makes the therapeutic journey possible in all its phases and depths.

Funding

The author did not receive any funding for this research.

Data Availability Statement

This is a theoretical paper based on literature review and conceptual analysis. No primary clinical data, patient interviews, or new empirical research were conducted.

Conflicts of Interest

The author report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Bakhtin, Mikhail M. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Baranger, W. , and M. Baranger. (1961) La situación analítica como campo dinámico. Revista Uruguaya de Psicoanálisis 4: 3-54. [The Analytical Situation as a dynamical Field].

- Bion, W. R. 1970. Attention and Interpretation. London: Tavistock.

- Bion, W. R. 1962. Learning from Experience. London: Heinemann.

- Bolognini, S. 2002. L’empatia psicoanalitica [Psychoanalytic Empathy]. Bollati Boringhieri.

- Bleger, J. 1967. “Psycho-Analysis of the Psycho-Analytic Frame.” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 48: 511–519.

- Bromberg, Philip M. 2011. “The Shadow of the Tsunami: and the Growth of the Relational Mind.” New York: Routledge.

- Cavicchioli, G. (Ed.) 2013. Io-tu-noi: L’intersoggettività duale e gruppale in psicoanalisi [I-You-Us: Dual and Group Intersubjectivity in Psychoanalysis]. Franco Angeli.

- Civitarese, G. 2013. Il campo analitico e le sue trasformazioni [The Analytic Field and Its Transformations]. Bollati Boringhieri.

- Civitarese, G. 2016. Truth and the Unconscious in Psychoanalysis. London: Routledge.

- Civitarese, G. 2023. Introduzione alla teoria del campo analitico [Introduction to the Theory of the Analytic Field]. Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

- Civitarese, G. 2022. “A Conversation with Giuseppe Civitarese.” Revista Portuguese de Psicanalise 41 (2): 92–23.

- Corrao, F. 1986. “La risposta dell’analista e le trasformazioni del campo” [The Analyst’s Response and the Transformations of the Field].” Psicoanalisi e metodo 1: 35–46.

- Einstein, Albert. 1915. “Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation.” Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin: 844-847.

- Ferro, A. 2002. Fattori di malattia, fattori di guarigione: Genesi della sofferenza e cura psicoanalitica [Factors of Illness, Factors of Healing: Genesis of Suffering and Psychoanalytic Care]. Bollati Boringhieri.

- Ferro, Antonino. 2005. “Seeds of Illness, Seeds of Recovery: The Genesis of Suffering and the Role of Psychoanalysis.” London: Routledge.

- Ferro, A. 2006. Tecnica e creatività: Il lavoro analitico [Technique and Creativity: The Analytic Work]. Raffaello Cortina.

- Ferro, A. , and R. Basile, eds. 2009. The Analytic Field. A Clinical Concept. London: Karnac.

- Ferro, A. , and G. Civitarese. 2015. The Analytic Field and Its Transformations. London: Karnac.

- Feynman, R. 1970. The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol II. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley Longman. [CrossRef]

- Freud, S. 1913. “On Beginning the Treatment.” In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works, Vol. 12. London: Hogarth Press.

- Geroch, R. 1981. General Relativity from A to B. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [CrossRef]

- Gill, M. M. 1994. Psychoanalysis in Transition: A Personal View. New York: Analytic Press.

- Green, André. 1975. “The Analyst, Symbolization and Absence in the Analytic Setting.” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 56, no. 1: 1-22.

- Grotstein, J. S. 2007. A Beam of Intense Darkness: Wilfred Bion’s Legacy to Psychoanalysis. London: Karnac.

- Kächele, H. , and H. Thomä. 1985. Lehrbuch der psychoanalytischen Therapie. 1. Grundlagen. [Theory and Practice of Psychoanalysis]. Berlin: Springer.

- Langs, R. 1989. The Technique of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy. Volumes 1 & 2. New York: Jason Aronson.

- Laplanche, J. 2006. Problématiques VI: L’après-coup [Problematics VI: Afterwardsness]. Paris: PUF.

- Lenti, Gabriele. 2014. Psicoanalisi e teoria della complessità nella scienza contemporanea [Psychoanalysis and Complexity Theory in Contemporary Science] Roma: Edizioni Alpes.

- Lenti, Gabriele. 2016. Nuove proposte applicative nella psicoanalisi e nella teoria della complessità. [New Application Proposals in Psychoanalysis and Complexity Theory.] Roma: Edizioni Alpes.

- Levine, H. B., D. Scarfone, S. H. Ornstein, and G. S. Reed, eds. 2013. Unrepresented States and the Construction of Meaning. London: Karnac.

- Levine, H. B. 2021. “Stepping into the Field: Bion and the Post-Bionian Field Theory of Antonino Ferro and the Pavia Group.” European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling 24 (4): 1–16.

- Lorenz, E. N. 1963. “Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow.” Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 20: 130–141.

- Mandelbrot, B. B. 1982. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

- Maturana, H. R. , and F. J. Varela. 1980. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. Netherland: Kluwer.

- McMullin, E. 2002. “The Origins of the Field Concept in Physics.” Physics in Perspective 4 (1): 13–39.

- McWilliams, N. 2004. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: A Practitioner’s Guide. New York: Guilford.

- Mitchell, Stephen A. 2000. “Relationality: From Attachment to Intersubjectivity.” Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press. [CrossRef]

- Nissen, B. 2023. “Kairos and Chronos: Clinical-Psychoanalytic Reflections on Time.” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 104 (3): 452–66. [CrossRef]

- Ogden, T. H. 1989. The Primitive Edge of Experience. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

- Ogden, T. H. 1994. “The Analytic Third: Working with Intersubjective Clinical Facts.” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 75: 3–19.

- Ogden, T. H. 1997. Reverie and Interpretation: Sensing Something Human. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

- Ogden, T. H. 2004 a. “Projective Identification and the Subjective Experience of the Analyst.” In The Primitive Edge of Experience, 139–161. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

- Ogden, T. H. 2004 b. “On Holding and Containing, Being and Dreaming.” International Journal of Psychoanalysis 85(6): 1349-1364.

- Quinodoz, Jean-Michel. 1996 “The sense of solitude in the psychoanalytic encounter.” Int J Psychoanal. Jun;77 ( Pt 3):481-96.

- Reik, Theodor. “Listening with the Third Ear: The Inner Experience of a Psychoanalyst.” New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1948.

- Riolo, F. 2019. “Teorie psicoanalitiche a confronto. Il modello di campo.” [Psychoanalytic Theories in Comparison. The Field Model]. Rivista di Psicoanalisi 65 (4): 1017–1040.

- Schroeder, D. V. 1995. An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory. Reading, MA: Westview Press.

- Stern, D. N., L. W. Sander, J. P. Nahum, A. M. Harrison, K. Lyons-Ruth, A. C. Morgan, N. Bruschweiler-Stern, and E. Z. Tronick. 1998. “Non-Interpretive Mechanisms in Psychoanalytic Therapy: The ‘Something More’ Than Interpretation.” The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 79: 903–921.

- Stern, D. B. 2015. “Relational Freedom: Emergent Properties of the Interpersonal Field.” New York: Routledge.

- Turner, V. W. 1996. The Ritual Process. London: Routledge.

- von Glasersfeld, E. 1995. Radical Constructivism: A Way of Knowing and Learning. London: The Falmer Press.

- Winnicott, Donald W. Playing and Reality. London: Tavistock Publications, 1971.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).