Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment of Studies

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Data Visualization and Tabulation

2.7. Software and Statistical Packages

3. Results

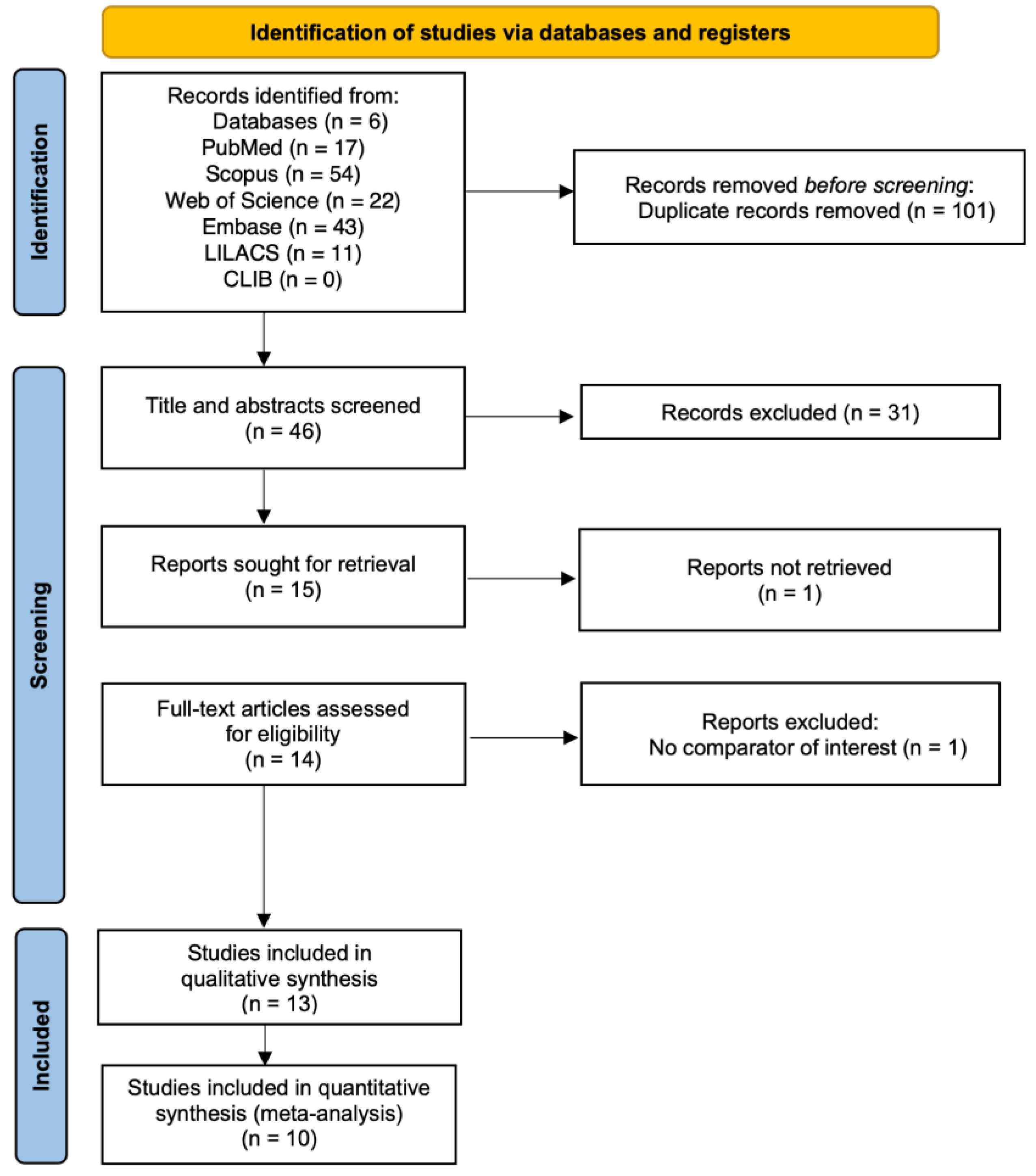

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

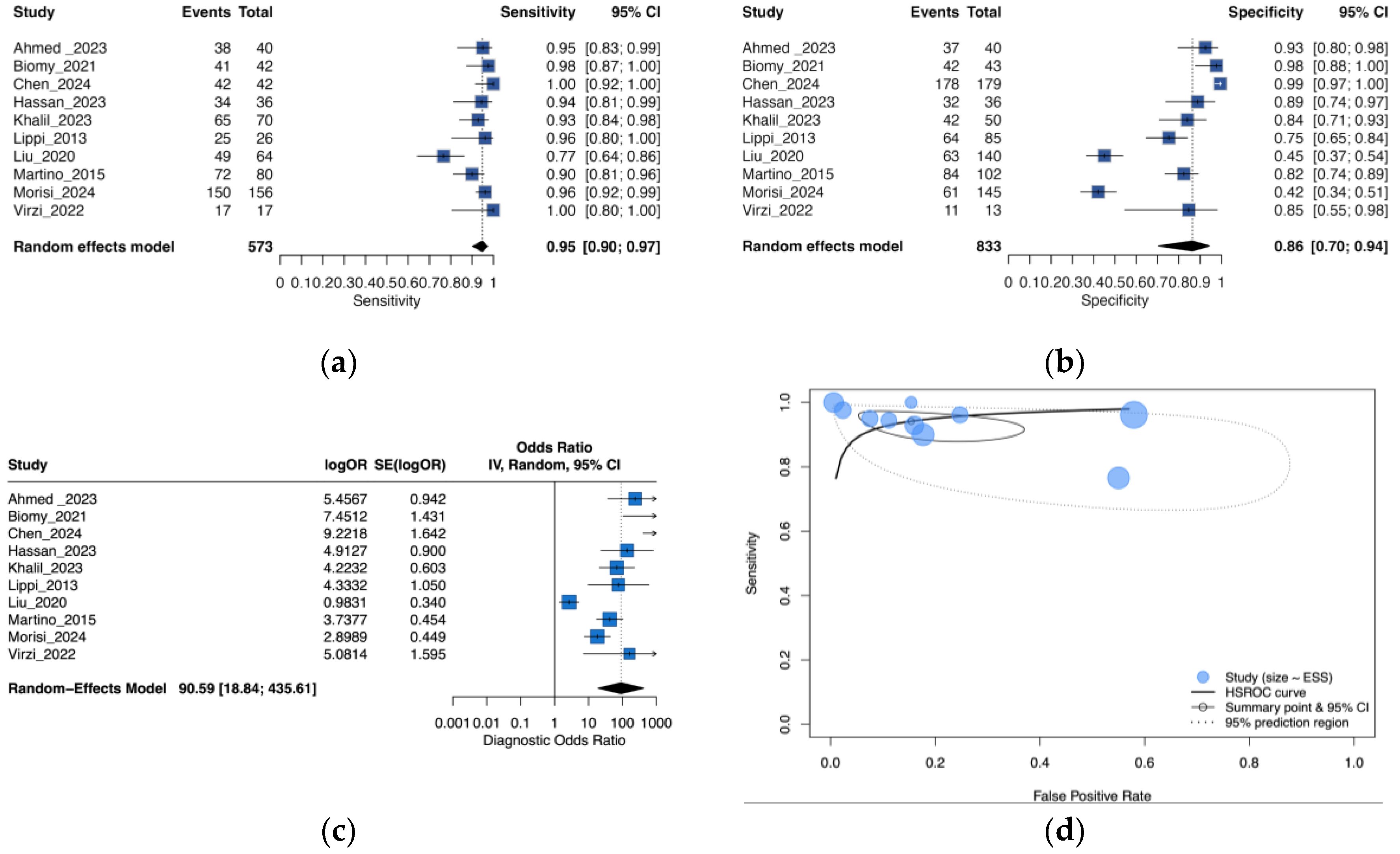

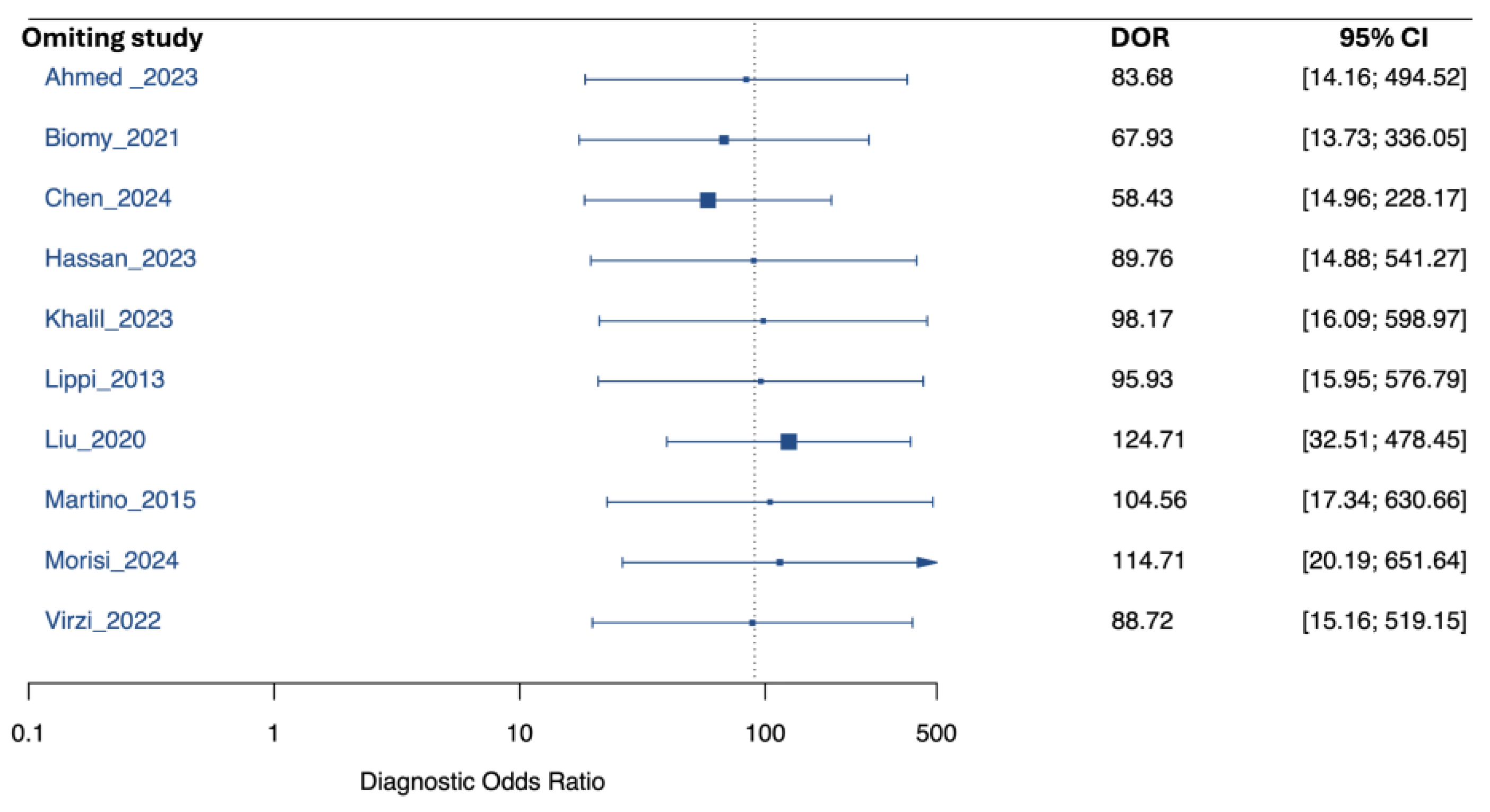

3.3. Performance of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin for Detection of SBP and PDAP

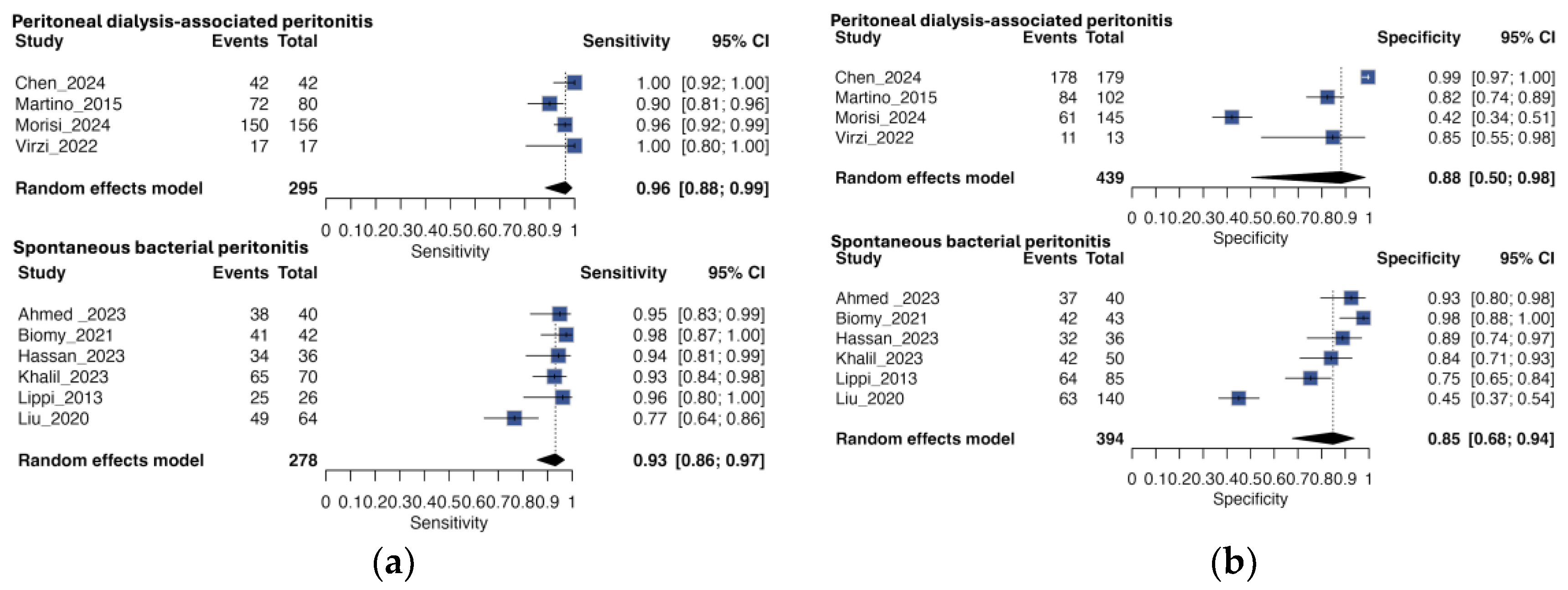

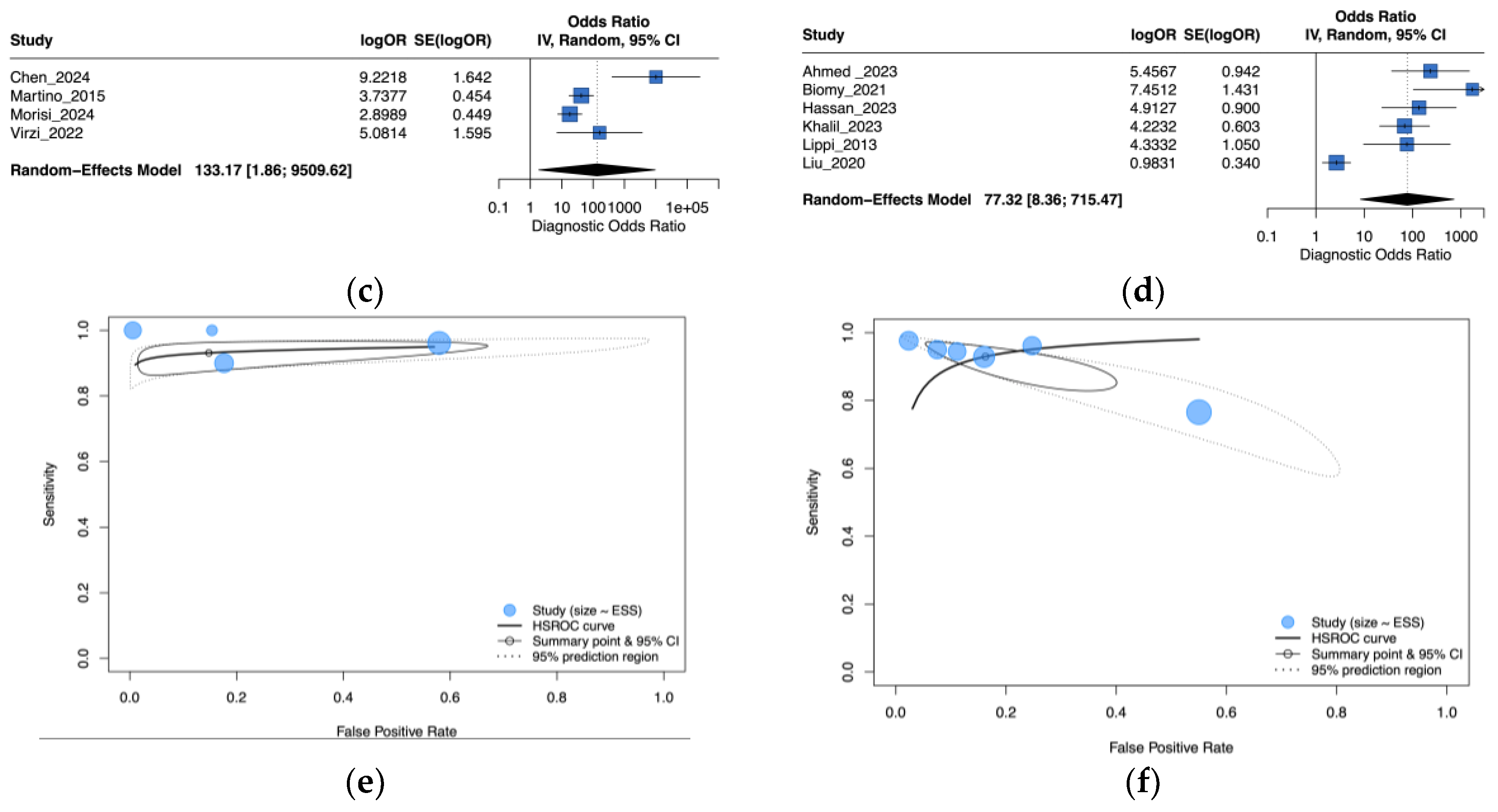

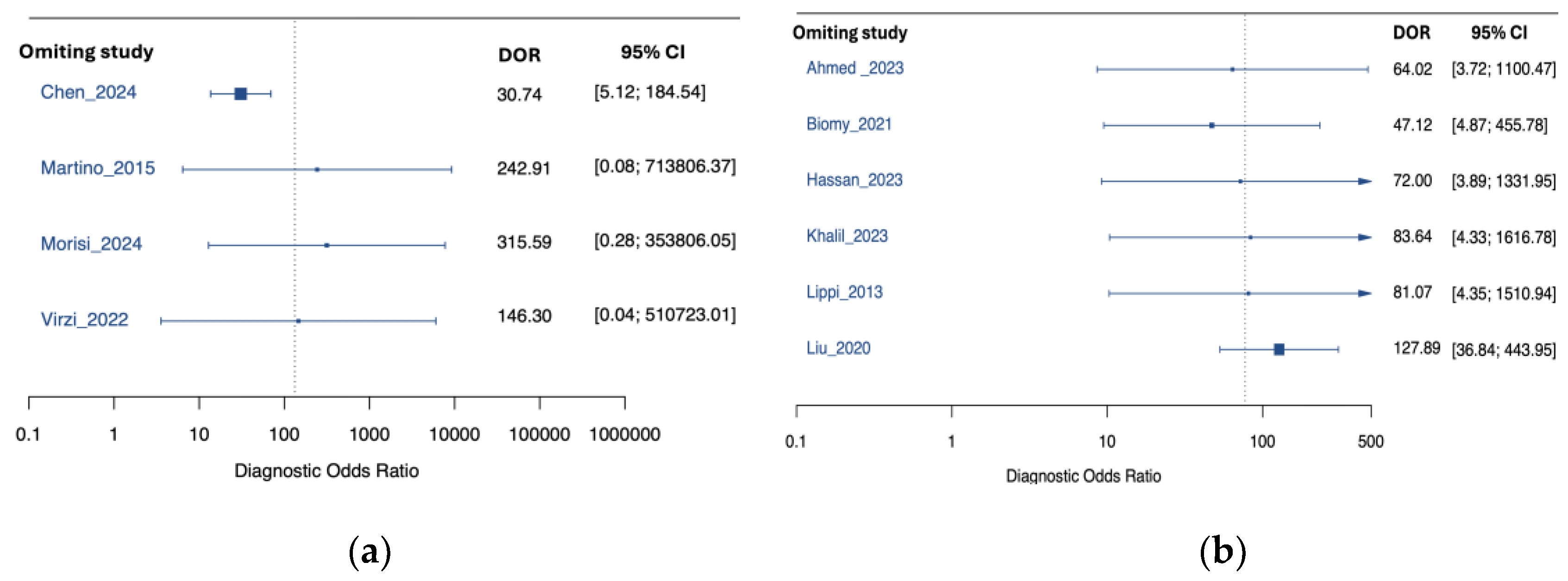

3.4. Subgroup Analysis by Peritonitis Type

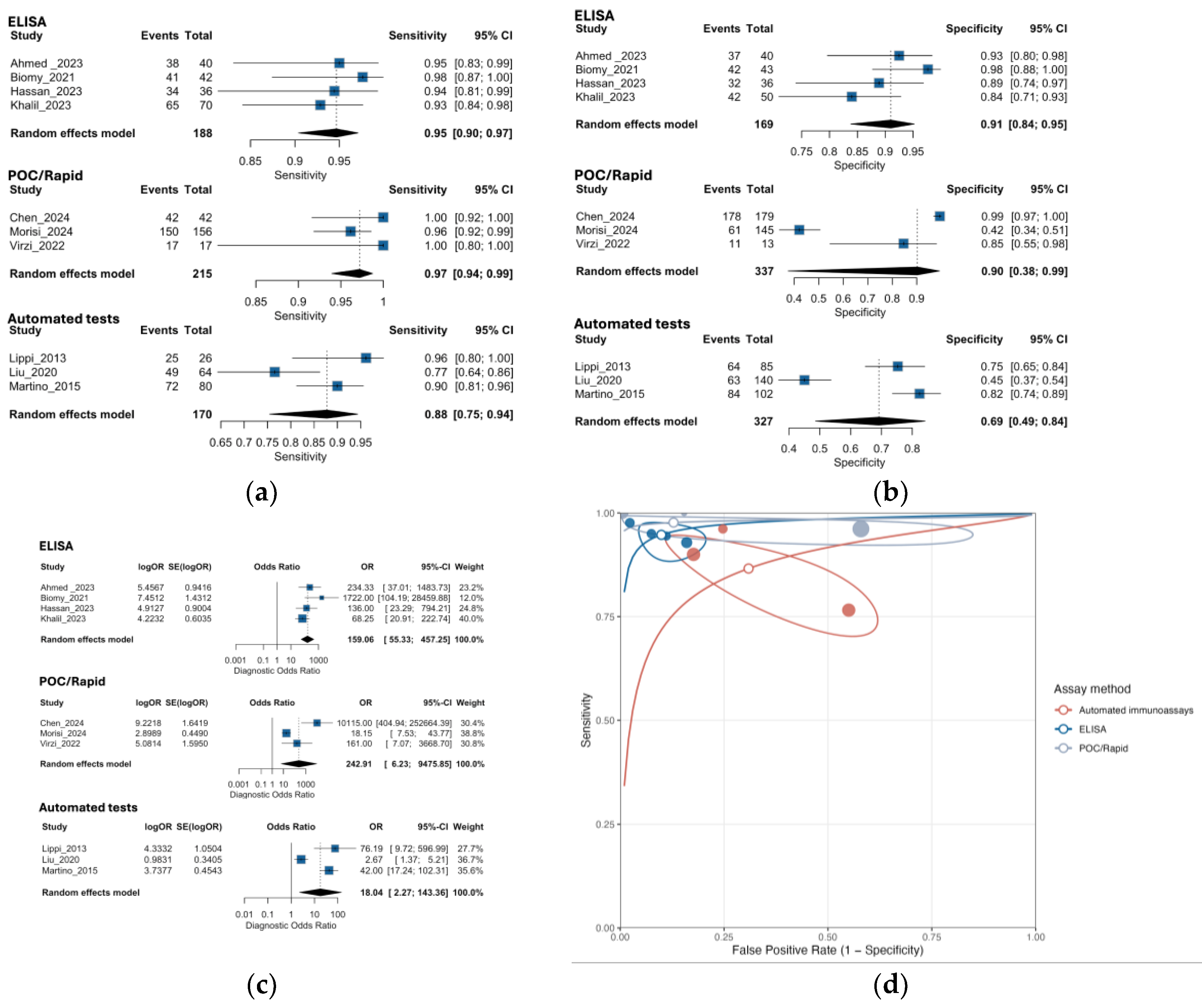

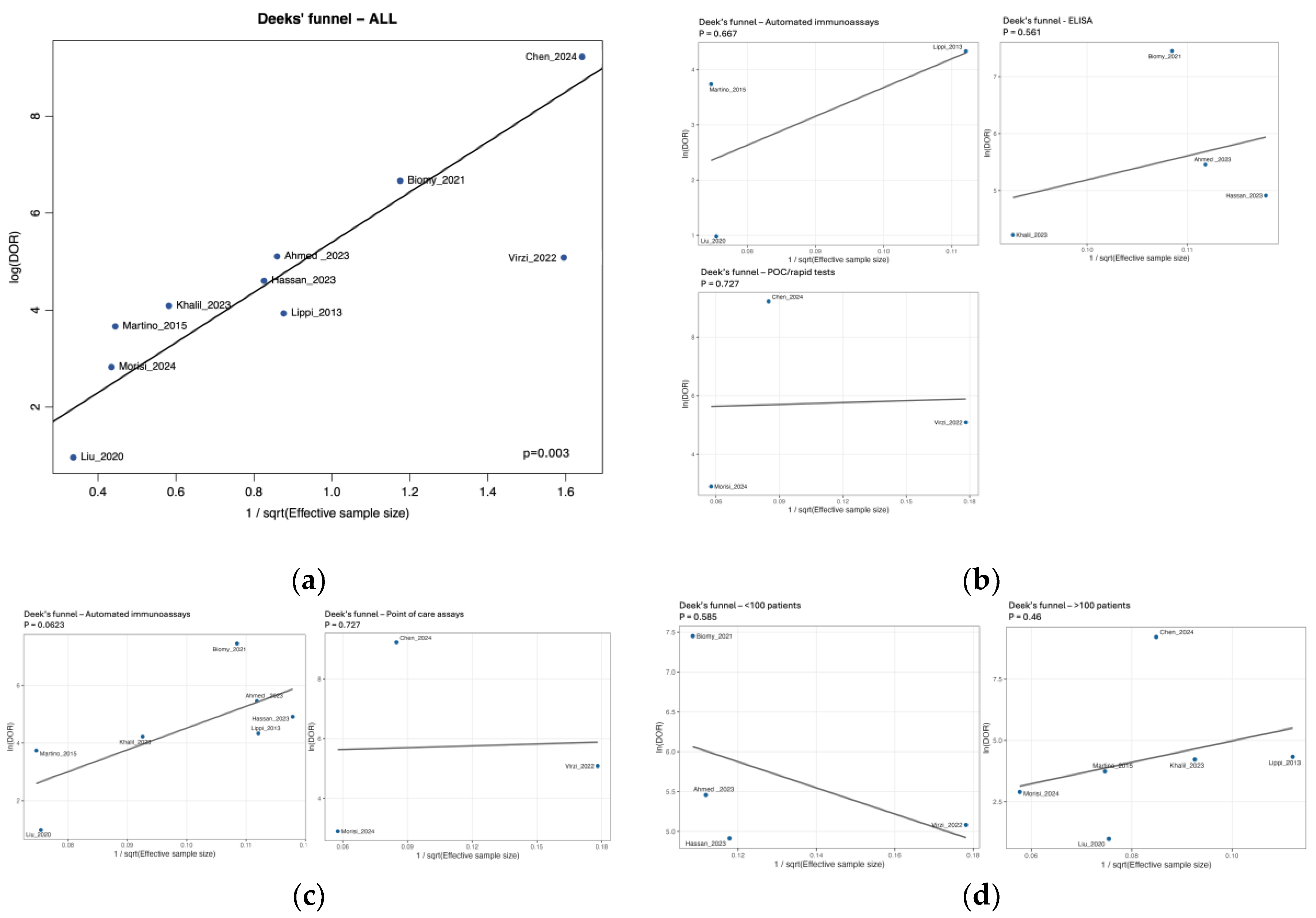

3.5. Subgroup Analysis by NGAL Assay Method

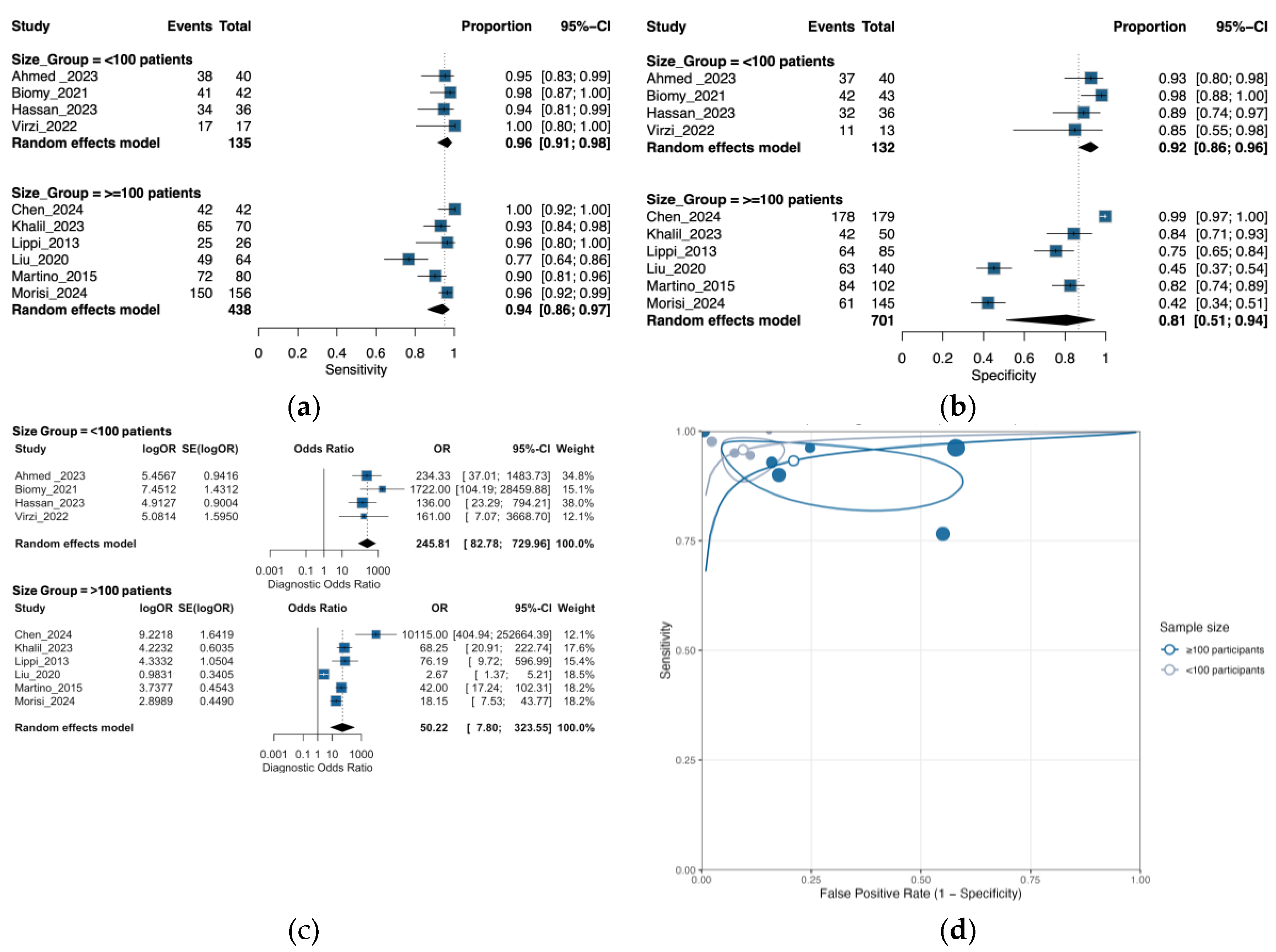

3.6. Subgroup Analysis by Sample Size

3.7. Risk of Bias

3.8. Certainty of the Evidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AASLD ANC |

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Absolute Neutrophil Count |

| APD | Automated Peritoneal Dialysis |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CAPD | Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis |

| CBC | Complete Blood Count |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CNNA | Culture-Negative Neutrocytic Ascites |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| EASL ELISA |

European Association for the Study of the Liver Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| DOR GI |

Diagnostic odds ratio Gastrointestinal |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| HSROC INR |

Hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic International Normalized Ratio |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| ISPD | International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| NGALds | NGAL Dipstick Test |

| NGALlab | Laboratory-based NGAL Test |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| PCT | Procalcitonin |

| PD | Peritoneal Dialysis |

| PDAP | Peritoneal Dialysis-Associated Peritonitis |

| PMN | Polymorphonuclear Neutrophils |

| PMNL | Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes |

| POC PPV |

Point-of-care Positive Predictive Value |

| QUADAS-2 | Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SBP | Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis |

| SROC UTI |

Summary receiver operating characteristic Urinary Tract Infection |

References

- Teitelbaum, I. Peritoneal Dialysis. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 385, 1786–1795. [CrossRef]

- Tay, P.W.L.; Xiao, J.; Tan, D.J.H.; Ng, C.; Lye, Y.N.; Lim, W.H.; Teo, V.X.Y.; Heng, R.R.Y.; Yeow, M.W.X.; Lum, L.H.W.; et al. An Epidemiological Meta-Analysis on the Worldwide Prevalence, Resistance, and Outcomes of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis in Cirrhosis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 693652. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Freha, N.; Michael, T.; Poupko, L.; Estis-Deaton, A.; Aasla, M.; Abu-Freha, O.; Etzion, O.; Nesher, L. Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis among Cirrhotic Patients: Prevalence, Clinical Characteristics, and Outcomes. J Clin Med 2021, 11, 227. [CrossRef]

- Young, E.W.; Zhao, J.; Pisoni, R.L.; Piraino, B.M.; Shen, J.I.; Boudville, N.; Schreiber, M.J.; Teitelbaum, I.; Perl, J.; McCullough, K. Peritoneal Dialysis-Associated Peritonitis Trends Using Medicare Claims Data, 2013-2017. Am J Kidney Dis 2023, 81, 179–189. [CrossRef]

- Flythe, J.E.; Watnick, S. Dialysis for Chronic Kidney Failure: A Review. JAMA 2024, 332, 1559–1573. [CrossRef]

- Nardelli, L.; Scalamogna, A.; Ponzano, F.; Sikharulidze, A.; Tripodi, F.; Vettoretti, S.; Alfieri, C.; Castellano, G. Peritoneal Dialysis Related Peritonitis: Insights from a Long-Term Analysis of an Italian Center. BMC Nephrol 2024, 25, 163. [CrossRef]

- Davenport, A. Peritonitis Remains the Major Clinical Complication of Peritoneal Dialysis: The London, UK, Peritonitis Audit 2002-2003. Perit Dial Int 2009, 29, 297–302.

- Pérez Fontan, M.; Rodríguez-Carmona, A.; García-Naveiro, R.; Rosales, M.; Villaverde, P.; Valdés, F. Peritonitis-Related Mortality in Patients Undergoing Chronic Peritoneal Dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2005, 25, 274–284.

- Bajaj, J.S.; Kamath, P.S.; Reddy, K.R. The Evolving Challenge of Infections in Cirrhosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 384, 2317–2330. [CrossRef]

- Hung, T.-H.; Wang, C.-Y.; Tsai, C.-C.; Lee, H.-F. Short and Long-Term Mortality of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis in Cirrhotic Patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024, 103, e40851. [CrossRef]

- Santoiemma, P.P.; Dakwar, O.; Angarone, M.P. A Retrospective Analysis of Cases of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis in Cirrhosis Patients. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0239470. [CrossRef]

- Mekraksakit, P.; Suppadungsuk, S.; Thongprayoon, C.; Miao, J.; Leelaviwat, N.; Thongpiya, J.; Qureshi, F.; Craici, I.M.; Cheungpasitporn, W. Outcomes of Peritoneal Dialysis in Cirrhosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Perit Dial Int 2025, 45, 93–105. [CrossRef]

- Cullaro, G.; Kim, G.; Pereira, M.R.; Brown, R.S.; Verna, E.C. Ascites Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin Identifies Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis and Predicts Mortality in Hospitalized Patients with Cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 2017, 62, 3487–3494. [CrossRef]

- Virzì, G.M.; Mattiotti, M.; Milan Manani, S.; Gnappi, M.; Tantillo, I.; Corradi, V.; de Cal, M.; Giuliani, A.; Carta, M.; Giavarina, D.; et al. Peritoneal NGAL: A Reliable Biomarker for PD-Peritonitis Monitoring. J Nephrol 2023, 36, 2139–2141. [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.C.K.; Lam, M.F.; Tang, S.C.W.; Chan, L.Y.Y.; Tam, K.Y.; Yip, T.P.S.; Lai, K.N. Roles of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin in Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis-Related Peritonitis. J Clin Immunol 2009, 29, 365–378. [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, J.R.; Borregaard, N.; Cowland, J.B. Induction of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin Expression by Co-Stimulation with Interleukin-17 and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Is Controlled by IkappaB-Zeta but Neither by C/EBP-Beta nor C/EBP-Delta. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 14088–14100. [CrossRef]

- Jaberi, S.A.; Cohen, A.; D’Souza, C.; Abdulrazzaq, Y.M.; Ojha, S.; Bastaki, S.; Adeghate, E.A. Lipocalin-2: Structure, Function, Distribution and Role in Metabolic Disorders. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 142, 112002. [CrossRef]

- Nasioudis, D.; Witkin, S.S. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin and Innate Immune Responses to Bacterial Infections. Med Microbiol Immunol 2015, 204, 471–479. [CrossRef]

- Moschen, A.R.; Adolph, T.E.; Gerner, R.R.; Wieser, V.; Tilg, H. Lipocalin-2: A Master Mediator of Intestinal and Metabolic Inflammation. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2017, 28, 388–397. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Hassan, R.; Abd Elghafar Salem, G.; Mohamed ALsayed Refaat Mohamed, B.; Ahmed Zidan, A.; El-Gebaly, A.M. Prognostic Value of Ascitic Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin in Decompensated Liver Cirrhosis with Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis Patients; The Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine; 2023; Vol. 91, pp. 4511–4511;

- Lippi, G.; Caleffi, A.; Pipitone, S.; Elia, G.; Ngah, A.; Aloe, R.; Avanzini, P.; Ferrari, C. Assessment of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin and Lactate Dehydrogenase in Peritoneal Fluids for the Screening of Bacterial Peritonitis. Clin Chim Acta 2013, 418, 59–62. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, P.; Nie, C.; Ye, Q.; Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; Pang, G.; Han, T. The Value of Ascitic Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin in Decompensated Liver Cirrhosis with Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis 2020, 34. [CrossRef]

- Martino, F.; Scalzotto, E.; Giavarina, D.; Rodighiero, M.P.; Crepaldi, C.; Day, S.; Ronco, C. The Role of NGAL in Peritoneal Dialysis Effluent in Early Diagnosis of Peritonitis: Case-Control Study in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. Perit Dial Int 2015, 35, 559–565. [CrossRef]

- Lacquaniti, A.; Chirico, V.; Mondello, S.; Buemi, A.; Lupica, R.; Fazio, M.R.; Buemi, M.; Aloisi, C. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin in Peritoneal Dialysis Reflects Status of Peritoneum. J Nephrol 2013, 26, 1151–1159. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; M., Joanne E.;. Bossuyt, Patrick M.M.;. Boutron, Isabelle; Hoffmann, Tammy; Mulrow, Cynthia D.;. Shamseer, Larissa; Tetzlaff, Jennifer; Akl, Elie A.;. Brennan, Sue E.;. Chou, Roger; Glanville, Julie; Grimshaw, Jeremy M.;. Hróbjartsson, Asbjørn; Lalu, Manoj M.;. Li, Tianjing; Loder, Elizabeth; Mayo-Wilson, Evan; McDonald, Steve; McGuinness, Luke A; Stewart, Lesley A.;. Thomas, James; Tricco, Andrea C.;. Welch, Vivian; Whiting, Penny; Moher, David The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. International journal of surgery (London, England) 2021, 88, 105906–105906. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.K.-T.; Chow, K.M.; Cho, Y.; Fan, S.; Figueiredo, A.E.; Harris, T.; Kanjanabuch, T.; Kim, Y.-L.; Madero, M.; Malyszko, J.; et al. ISPD Peritonitis Guideline Recommendations: 2022 Update on Prevention and Treatment. Perit Dial Int 2022, 42, 110–153. [CrossRef]

- Biggins, S.W.; Angeli, P.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Ginès, P.; Ling, S.C.; Nadim, M.K.; Wong, F.; Kim, W.R. Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management of Ascites, Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis and Hepatorenal Syndrome: 2021 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2021, 74, 1014. [CrossRef]

- EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Ascites, Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis, and Hepatorenal Syndrome in Cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology 2010, 53, 397–417. [CrossRef]

- QUADAS-2: A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies | Annals of Internal Medicine Available online: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Alshymaa A. Ahmed, Maha Roushdy Abd El Wahed, Marwan Elgohary, Fatma Atef Ibrahim,Rehab Mohamed Ateya Ahmed_ 2023_Value of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin in Serum and Peritoneal Fluids in the Diagnosis of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis and the Prediction of in Hospital Mortality. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol 2023, 30, e934–e955.

- Biomy, H.A.; Ramadan, N.E.; Ameen, S.G.; Kandil, A.E.D.I.; Galal, Z.W. Evaluation of Ascitic Fluid Neutrophil Gelatinase Associated Lipocalin in Patients with Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis. Benha Medical Journal 2021, 38, 951–961. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, T.; Kong, G.; Lyu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Chen, Q. Utility of Homodimer Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin Rapid Test Kit for the Diagnosis of Peritoneal Dialysis-Associated Peritonitis. Chinese Journal of Nephrology 2024, 40, 868–874. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, F.O.; Mandour, S.S.M.S.; Bedira, I.S.; Elkhadry, S.; Ibrahim, A.R.; Abdelmageed, N.; El -shemy, E.; El-refai, H.A. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin-2 and Macrophage Antigen -1 in Cirrhotic Patients Infected with Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Egyptian Journal of Medical Microbiology 2023, 32, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Martino, F.K.; Filippi, I.; Giavarina, D.; Kaushik, M.; Rodighiero, M.P.; Crepaldi, C.; Teixeira, C.; Nadal, A.F.; Rosner, M.H.; Ronco, C. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin in the Early Diagnosis of Peritonitis: The Case of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin. Contrib Nephrol 2012, 178, 258–263. [CrossRef]

- Morisi, N.; Virzì, G.M.; Barajas, J.D.G.; Diaz-Villavicencio, B.; Manani, S.M.; Zanella, M. Validation of Peritoneal Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin as a Biomarker for Peritonitis: A Comparison between Laboratory-Base Method and Rapid Stick Test. Journal of Translational Critical Care Medicine 2023, 5. [CrossRef]

- Virzì, G.M.; Milan Manani, S.; Marcello, M.; Costa, E.; Marturano, D.; Tantillo, I.; Lerco, S.; Corradi, V.; De Cal, M.; Martino, F.K.; et al. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (NGAL) in Peritoneal Dialytic Effluent: Preliminary Results on the Comparison between Two Different Methods in Patients with and without Peritonitis. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Virzi, G.M.; Morisi, N.; Manani, S.M.; de Cal, M.; Tantillo, I.; Donati, G.; Ronco, C.; Zanella, M. #996 Validation of Peritoneal NGAL as a Biomarker for Peritonitis: A Comparison between Laboratory-Base Method and Rapid Stick Test. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2024, 39, gfae069-0927–0996. [CrossRef]

| Database | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed / MEDLINE | ("neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin"[Title/Abstract] OR "NGAL"[Title/Abstract] OR "lipocalin-2"[Title/Abstract]) AND ("peritoneal dialysis"[Title/Abstract] OR "dialysis effluent"[Title/Abstract] OR "peritoneal fluid"[Title/Abstract] OR "ascites"[Title/Abstract]) AND ("peritonitis"[Title/Abstract] OR "spontaneous bacterial peritonitis"[Title/Abstract] OR "secondary bacterial peritonitis"[Title/Abstract] OR "infection"[Title/Abstract]) |

| Embase | ('neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin':ab,ti OR 'NGAL':ab,ti OR 'lipocalin 2':ab,ti) AND ('peritoneal dialysis':ab,ti OR 'dialysis effluent':ab,ti OR 'peritoneal fluid':ab,ti OR 'ascites':ab,ti) AND ('peritonitis':ab,ti OR 'spontaneous bacterial peritonitis':ab,ti OR 'secondary bacterial peritonitis':ab,ti OR 'infection':ab,ti) |

| Cochrane Library | ("neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin" OR NGAL OR "lipocalin-2") AND ("peritoneal dialysis" OR "dialysis effluent" OR "peritoneal fluid" OR "ascites") AND (peritonitis OR "spontaneous bacterial peritonitis" OR "secondary bacterial peritonitis" OR infection) |

| LILACS | ("neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin" OR NGAL OR "lipocalin-2") AND ("diálisis peritoneal" OR "efluente peritoneal" OR "líquido peritoneal" OR ascitis) AND (peritonitis OR "peritonitis bacteriana espontánea" OR "peritonitis bacteriana secundaria" OR infección) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY("neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin" OR NGAL OR "lipocalin-2") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY("peritoneal dialysis" OR "dialysis effluent" OR "peritoneal fluid" OR ascites) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(peritonitis OR "spontaneous bacterial peritonitis" OR "secondary bacterial peritonitis" OR infection) |

| WoS | TS=("neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin" OR NGAL OR "lipocalin-2") AND TS=("peritoneal dialysis" OR "dialysis effluent" OR "peritoneal fluid" OR ascites) AND TS=(peritonitis OR "spontaneous bacterial peritonitis" OR "secondary bacterial peritonitis" OR infection) |

| Study (Author, Year, Location) |

Study design | Peritonitis type | Participant characteristics | NGAL measurement method | Diagnostic criteria for peritonitis |

Diagnostic performance metrics |

QUADAS-2 risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al., 2023 [30], Egypt | Case-cohort study with prospective follow-up | Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | - Total number of participants: 80 Chronic liver disease patients with ascites - Mean/median age: SBP group: 60.6 ± 12.5 years; Non-SBP group: 57.8 ± 10.2 years - Gender distribution: SBP group: 55% male, 45% female; Non-SBP group: 60% male, 40% female - Specific inclusion criteria: Patients with chronic liver disease and ascites admitted to Internal Medicine Department - Specific exclusion criteria: Acute renal impairment, renal replacement therapy, secondary peritonitis, intra-abdominal surgery or malignancy |

- Type of assay: ELISA (SunRed Biotech) - Platform/format: ELISA (laboratory) - Manufacturer/kit: SunRed Biotech - Analyte/target: Total NGAL - Diagnostic cut-off (standardized): 297.8 ng/mL - Original reporting units: ng/mL (standardized to ng/mL) - Cut-off selection rule: reported |

- Neutrophil count threshold: PMN ≥ 250 cells/mm³- Microbiological confirmation method: Positive ascitic fluid culture for single organism- - Clinical criteria: Presence of clinical symptoms and signs - Additional diagnostic parameters: Exclusion of acute renal impairment, renal replacement therapy and secondary peritonitis |

- Sensitivity: 95.6% - Specificity: 92.5% - Positive Predictive Value: 95% - Negative Predictive Value: 95% - AUC: 0.845 - Accuracy: 95% |

Domain 1: Patient Selection: Patients were appropriately selected with defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Domain 2: Index Test: Serum and ascitic Lipocalin-2 were measured by standardized ELISA, with diagnostic performance evaluated by ROC analysis. Domain 3: Reference Standard: SBP was diagnosed by PMN count and/or positive culture. Domain 4: Flow and Timing: Samples were collected at paracentesis, ensuring consistent timing. Overall risk: Moderate |

| Biomy et al., 2021 [31], Egypt | Cross-sectional study | Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | - Total number of participants: 85 - Patient population: Cirrhosis patients with ascites - Mean age: SBP group: 61±7.81 years; Non-SBP group: 56.44±6.73 years - Gender distribution: SBP group: Male: 28 (66.67%), Female: 14 (22.2%); Non-SBP group: Male: 28 (65.12%), Female: 15 (34.88%) - Specific inclusion/exclusion criteria: Not reported |

- Type of assay: ELISA (Bioassay Science Laboratory E1719Hu) - Platform/format: ELISA (laboratory) - Manufacturer/kit: Bioassay Science Laboratory E1719Hu - Analyte/target: Total NGAL - Diagnostic cut-off (standardized): 100.8 ng/mL - Original reporting units: ng/dL (standardized to ng/mL) |

- Neutrophil count threshold: PMN >250 cells/mm³ - Microbiological confirmation method: Not specified - Clinical criteria: Abdominal pain, fever, GI bleeding - Additional diagnostic parameters: Ascitic fluid protein, glucose, albumin, SAAG |

- Sensitivity: 97.62% - Specificity: 97.67% - Positive predictive value: 97.62% - Negative predictive value: 97.67% - AUC: 0.974 |

Domain 1: Patient Selection: Cirrhotic ascites patients were included with comprehensive exclusion criteria to reduce bias. Domain 2: Index Test: Ascitic NGAL was determined using standardized ELISA, and ROC analysis was used to assess diagnostic efficiency. Domain 3: Reference Standard: SBP was diagnosed by ascitic fluid PMN count ≥250/mm3. Domain 4: Flow and Timing: Ascitic fluid samples were collected consistently for NGAL measurement in relation to SBP diagnosis. Overall risk: High |

| Chen et al., 2024 [32], China |

Multicenter prospective observational study | Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis | - Total number of participants: 221- PD patients from 4 hospitals - Mean/median age: PDAP group: 57.8±13.9 years; Non-PDAP group: 51.2±12.9 years - Gender distribution: PDAP group: 59.5% male, 40.5% female; Non-PDAP group: 59.8% male, 40.2% female - Specific inclusion criteria: Age >18 years, continuous PD treatment ≥3 months - Specific exclusion criteria: Prior antibiotic use before sampling, unclear sample labeling, contaminated samples, repeat cases, red-colored PD effluent |

- Type of assay: Rapid immunochromatographic test - Specific kit or technology used: H-NGAL rapid test kit (Qingdao Hantang Biotechnology Co.)- NGAL measurement units: Qualitative (positive/negative) - Test formats: Cassette, strip, and pen types - Reading time: 10-15 minutes |

- ISPD criteria (at least 2 of):1) Clinical features: abdominal pain and/or cloudy PD effluent2) PD effluent WBC count >100/μl or >0.1×10⁹/L (dwell time ≥2h) or PMN >50%3) Positive PD effluent culture | - Sensitivity: 100% (95% CI 91.62%-100%) - Specificity: 99.44% (95% CI 96.90%-99.90%) - Accuracy: 99.55% (95% CI 97.48%-99.92%) - Positive Predictive Value: 97.67% (95% CI 87.94%-99.59%) - Negative Predictive Value: 100% (95% CI 97.89%-100%) - Kappa value: 0.985 (95% CI 0.956-1.000) |

Domain 1: Patient Selection: Patients were enrolled from multiple centers with clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, ensuring a relevant sample. Domain 2: Index Test: The H-NGAL rapid test was performed by both professionals (blinded) and patients, using various formats to ensure robust evaluation. Domain 3: Reference Standard: PDAP diagnosis strictly adhered to international guidelines, utilizing a combination of clinical, cellular, and microbiological criteria. Domain 4: Flow and Timing: Samples were collected at the time of enrollment, and the rapid test results (10-15 minutes) allowed for timely diagnostic assessment. Overall risk: Moderate |

| Cullaro et al., 2017 [13], USA | Prospective cohort study | Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | - Total number of participants: 146 - Hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and ascites - Mean/median age: SBP group: 56.6±9.62 years; Non-SBP group: 59.9±10.9 years - Gender distribution: SBP group: 55% male, 45% female; Non-SBP group: 56% male, 44% female- Specific inclusion criteria: Adult patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites undergoing clinically indicated paracentesis - Specific exclusion criteria: Ascites due to non-cirrhotic causes, recent abdominal surgery, solid organ transplant recipients, documented colitis or enteritis |

- Type of assay: ELISA - Specific kit or technology used: AntibodyShop, Gentofte, Denmark - NGAL measurement units: ng/mL - Limit of detection: 0.5-4.0 ng/mL Diagnostic cut-off (standardized): 230.05 ng/mL - Original reporting units: ng/mL - Intra-assay variation: 2.1% (range 1.3-4.0) |

Neutrophil count threshold: ANC ≥250 cells/mm³ - Microbiological confirmation method: Blood, urine, or ascites cultures - Clinical criteria: Not specified- Additional diagnostic parameters: None |

- For SBP diagnosis: - c-statistic (AUC): 0.68 - For mortality prediction: Sensitivity: 73.3% (cutoff >221.3 ng/mL), Specificity: 71.2% (cutoff >221.3 ng/mL), AUC: 0.79 |

Domain 1: Patient Selection: Low risk - consecutive patients with clear inclusion/exclusion criteria Domain 2: Index Test: Low risk - ELISA performed with standardized protocol, blinded to reference standard Domain 3: Reference Standard: Low risk - ANC ≥250 cells/mm³ is standard criterion Domain 4: Flow and Timing: Low risk - samples collected on day of paracentesis Overall risk: Low |

| Hassan et al., 2023 [20], Egypt | Case-control study | Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis |

-Total number of participants: 72 - Patients with cirrhotic liver and ascites- Mean/median age: Not reported - Gender distribution: Not reported- Specific inclusion criteria: All patients diagnosed as cirrhotic based on clinical and laboratory tests with ascites caused by chronic liver illness - Specific exclusion criteria: Cirrhotic patients with HCC, peritonitis due to any cause other than SBP, portal hypertension and ascites from non-cirrhotic causes, liver or organ transplantation, renal diseases |

- Type of assay: ELISA - Specific kit or technology used: Human Lipocalin linked with Neutrophil Gelatinase Kit, Sun Red bio company, China - NGAL measurement units: ng/mL - Threshold values used for diagnosis: ≥230.05 ng/mL |

- Neutrophil count threshold: PMNL count ≥250/mm³ - Microbiological confirmation method: Positive fluid cultures with single organism culture isolation - Clinical criteria: Clinical presence of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice or hematemesis and melena - Additional diagnostic parameters: Laboratory tests (CBC platelet <150000, liver function test albumin<3.5, INR >1.1) |

- Sensitivity: 94.4% - Specificity: 88.9% - Positive Predictive Value: 89.5% - Negative Predictive Value: 94.1% - AUC: 0.989- Accuracy: 91.7% |

Domain 1: Patient Selection: Moderate risk - case-control design with clear inclusion/exclusion criteria Domain 2: Index Test: Low risk - ELISA performed with standardized protocol Domain 3: Reference Standard: Low risk - PMNL count ≥250/mm³ and/or positive culture Domain 4: Flow and Timing: Low risk - samples collected at paracentesis Overall risk: Moderate |

| Khalil et al., 2023 [33], Egypt | Case-control study | Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and Culture-negative neutrocytic ascites |

-Total number of participants: 150 - Cirrhotic patients divided into infected (n=100) and non-infected (n=50) - SBP subgroup: 55 patients- CNNA subgroup: 15 patients- UTI subgroup: 30 patients- Mean/median age: Not reported- Gender distribution: Not reported - Specific inclusion criteria: Patients aged ≥18 years with liver cirrhosis and ascites - Specific exclusion criteria: Antibiotic treated patients, renal failure, HCC, malignant ascites, septicemia, secondary bacterial peritonitis |

- Type of assay: ELISA (DRG GmbH) - Platform/format: ELISA (laboratory) - Manufacturer/kit: DRG GmbH - Analyte/target: Total NGAL - Diagnostic cut-off (standardized): 110.72 ng/mL - Original reporting units: ng/mL (standardized to ng/mL) - Cut-off selection rule: reported |

- Neutrophil count threshold: AF neutrophils count ≥250×10³ cells/μL - Microbiological confirmation method: Positive ascitic fluid culture for SBP; negative culture for CNNA - Clinical criteria: Clinical symptoms and signs - Additional diagnostic parameters: Mac-1 expression by flow cytometry |

- Sensitivity: 92.7% (CI: [0.82, 0.98]) - Specificity: 84% (CI: [0.75, 0.91]) - Positive Predictive Value: 0.77 (CI: [0.65, 0.86]) - Negative Predictive Value: 0.95 (CI: [0.88, 0.98]) - Area under the ROC curve (AUC): 0.899 (CI: [0.848, 0.951]) |

Domain 1: Patient Selection: Moderate risk - case-control design with clear inclusion/exclusion criteria Domain 2: Index Test: Low risk - ELISA and flow cytometry performed with standardized protocols Domain 3: Reference Standard: Low risk - standard criteria for SBP and CNNA Domain 4: Flow and Timing: Low risk - samples collected within 6h after paracentesis Overall risk: Moderate |

| Lippi et al., 2013 [21], Italy | Cross-sectional study | Bacterial peritonitis (various causes) | - Total number of participants: 111 - Patient population: Patients with new onset nonmalignant ascites - Mean/median age: Not reported - Gender distribution: Not reported - Specific inclusion criteria: Consecutive peritoneal fluids from patients with new onset nonmalignant ascites - Specific exclusion criteria: Visible clots in samples (7 samples excluded) |

- Type of assay: Automated NGAL Test™ (BioPorto Diagnostics A/S) on Beckman Coulter AU5822 - Platform/format: Immunoturbidimetric (laboratory) - Manufacturer/kit: BioPorto Diagnostics A/S - Analyte/target: Total NGAL - Diagnostic cut-off (standardized): 120.0 ng/mL |

- Neutrophil count threshold: PMN ≥250/μL - Microbiological confirmation method: Not used (68% on antibiotics) - Clinical criteria: New onset nonmalignant ascites - Additional diagnostic parameters: LDH, proteins, glucose |

- Sensitivity: 96% (95% CI: 80-100%) - Specificity: 75% (95% CI: 65-84%) - Positive Predictive Value: Not reported - Negative Predictive Value: Not reported - AUC: 0.89 (95% CI: 0.82-0.95) - Accuracy: Not reported |

Domain 1: Patient Selection: Low risk - consecutive patients with defined criteria Domain 2: Index Test: Low risk - predefined threshold, automated assay Domain 3: Reference Standard: Moderate risk - PMN count used instead of culture due to antibiotic use Domain 4: Flow and Timing: Low risk - all samples analyzed similarly Overall risk: Moderate |

| Liu et al., 2020 [22], China | Prospective cohort | Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis |

-Total number of participants: 204 decompensated liver cirrhosis patients with ascites - Mean/median age: Non-SBP group: 57.31 ± 12.91 years; SBP group: 59.64 ± 11.95 years - Gender distribution: Non-SBP group: 65.7% male, 34.3% female; SBP group: 76.6% male, 23.4% female - Specific inclusion criteria: Consecutive hospitalized patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis and ascites - Specific exclusion criteria: Pre-existing renal disease, presence of AKI at hospitalization, renal replacement therapy, secondary peritonitis, malignant diseases |

- Type of assay: Latex-enhanced immunoturbidimetric (BSBE) - Platform/format: Immunoturbidimetric (laboratory) - Manufacturer/kit: BSBE - Analyte/target: Total NGAL - Diagnostic cut-off (standardized): 108.95 ng/mL |

- Neutrophil count threshold: PMN ≥ 250 cells/mm³ and/or positive ascitic fluid culture - Microbiological confirmation method: Ascitic fluid culture (positive in 9 patients: 7 E. coli, 2 K. pneumoniae) - Clinical criteria: Clinical and biological diagnosis of decompensated liver cirrhosis |

- Sensitivity: 76.9% (for mortality prediction) - Specificity: 45.1% (for mortality prediction) - Positive Predictive Value: Not reported - Negative Predictive Value: Not reported - AUC: 0.702 (for mortality prediction in SBP patients) - Accuracy: Not reported |

Domain 1: Patient Selection: Consecutive patients with well-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Domain 2: Index Test: Ascitic NGAL measured by standardized latex-enhanced immunoturbidimetric method, with ROC analysis for diagnostic performance. Domain 3: Reference Standard: SBP diagnosed by PMN ≥ 250 cells/mm³ and/or positive ascitic fluid culture. Domain 4: Flow and Timing: Ascitic samples collected at paracentesis with consistent timing for all patients. Overall risk: Low |

| Martino F. et al., 2012 [34], Italy | Case–control study | Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis | - Total number of participants: 60 (30 cases, 30 controls) - Patient population: PD patients on treatment >3 months- Mean/median age: Cases: 66.5 years (IQR 52.2-73); Controls: 70 years (IQR 59.7-73.2) - Gender distribution: Cases: 73.3% male; Controls: 73.3% male - Specific inclusion criteria: PD patients >3 months with signs/symptoms of peritonitis (cases) or routine visit (controls) - Specific exclusion criteria: Not reported |

Type of assay: Chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay - Specific kit or technology used: Architect platform (Abbott Diagnostics) - NGAL measurement units: ng/mL - Threshold values used for diagnosis: Not specified (ROC analysis performed) |

ISPD guidelines: Cloudy peritoneal effluent with WBC > 100 × 10^6 cells/L (after ≥ 2 h dwell) with > 50% PMNs, abdominal pain and/or positive culture or Gram stain | - Sensitivity: Not reported- Specificity: Not reported- Positive Predictive Value: Not reported- Negative Predictive Value: Not reported -AUC peritoneal NGAL 0.99 (p < 0.001);AUC CRP 0.81 (p = 0.001), PCT 0.70 (p = 0.039), WBC 1.00 (p < 0.001) |

Domain 1: Patient Selection: Low risk - consecutive cases and matched controls Domain 2: Index Test: Unclear risk - no predefined threshold reported Domain 3: Reference Standard: Low risk - standard ISPD criteria used Domain 4: Flow and Timing: Low risk - appropriate sample collection Overall risk: Moderate |

| Martino et al., 2015 [23], Italy | Case-control study | Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis | - Total number of participants: 182 (91 cases, 91 controls) - Patient population: PD patients on treatment ≥90 days - Mean/median age: Peritonitis: 65 years (IQR 53.7-73.7); No peritonitis: 66.5 years (IQR 53.25-78)- Gender distribution: Peritonitis: 77.5% male; No peritonitis: 71.6% male- Specific inclusion criteria: Age >18 years, PD treatment ≥90 days, informed consent - Specific exclusion criteria: Peritonitis episode within 30 days before enrollment |

- Type of assay: Chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay - Specific kit or technology used: Architect platform (Abbott Diagnostics) - NGAL measurement units: ng/mL - Threshold values used for diagnosis: 85 ng/mL |

- Neutrophil count threshold: WBC > 100 cells/mm^3 (with at least 50% polymorphonuclear cells) - Microbiological confirmation method: Positive culture or Gram stain - Clinical criteria: Clinical signs and symptoms of peritoneal inflammation (pain, discomfort, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation) - Additional diagnostic parameters: Cloudy drainage |

- Sensitivity: 90% - Specificity: 82% - Positive predictive value: Not reported - Negative predictive value: Not reported - Area under the ROC curve (AUC): 0.936 - Accuracy: Not reported |

Domain 1: Patient Selection: Low risk - consecutive enrollment with clear criteria Domain 2: Index Test: Low risk - ROC-determined threshold, blinded analysis Domain 3: Reference Standard: Low risk - standard ISPD criteria Domain 4: Flow and Timing: Low risk - appropriate sample collection Overall risk: Low. |

| Morisi et al., 2024 [35], Italy | Retrospective analysis with cross-sectional elements | Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis | - Total number of participants: 301 peritoneal effluent samples - Patient population: PD patients (stable and with suspected/confirmed peritonitis) - Mean/median age: Not reported- Gender distribution: Not reported - Specific inclusion criteria: PD patients undergoing routine analysis or with suspected/confirmed peritonitis - Specific exclusion criteria: Not reported |

- Type of assay: Dipstick (NGALds) vs turbidimetric (NGALlab) - Platform/format: POC rapid (dipstick/lateral flow) - Manufacturer/kit: NGALds - Analyte/target: Total NGAL - Diagnostic cut-off (standardized): 100.0 ng/mL - Original reporting units: µg/L (standardized to ng/mL) |

- Neutrophil count threshold: White cell count and percentage of neutrophils (specific thresholds not reported) - Microbiological confirmation method: Not specified - Clinical criteria: ISPD criteria- Additional diagnostic parameters: NGALlab used as comparator |

- Sensitivity: 96% - Specificity: Not reported - Positive predictive value: 0.64 - Negative predictive value: 0.87 - Area under the ROC curve (AUC): 0.82 |

Domain 1: Patient Selection: Unclear risk - retrospective design, selection criteria not fully described Domain 2: Index Test: Low risk - threshold determined by statistical analysis Domain 3: Reference Standard: Unclear risk - reference standard not fully described Domain 4: Flow and Timing: Low risk - parallel testing performed Overall risk: Moderate |

| Virzì et al., 2022 [36], Vicenza,Italy | Observational, case–control study | Dialysis associated peritonitis | - Total number of participants = 30 PD patients (17 with peritonitis; 13 controls) - Age ≥ 18 years; on PD ≥ 30 days; informed consent - PD modality: 7 CAPD, 23 APD; treatment duration median 32.7 mo (IQR 11–49; range 1–88 mo) - Comorbidities: 9/30 diabetes; 30/30 hypertension; 12/30 CVD; none immunosuppressed; 86.6% on erythropoietin |

Laboratory-based NGAL: particle-enhanced turbidimetric immunoassay (BioPorto Diagnostics; range 50–3000 ng/mL; ≥ 200 ng/mL indicative of peritonitis). Point-of-care NGAL (NGALds): lateral-flow dipstick (BioPorto Diagnostics), semi-quantitative colour categories 25–600 ng/mL; read by two blinded operators |

ISPD guidelines: Cloudy peritoneal effluent with WBC > 100 × 10^6 cells/L (after ≥ 2 h dwell) with > 50% PMNs, abdominal pain and/or positive culture or Gram stain | Spearman’s ρ between NGALds and lab NGAL = 0.88 (p < 0.01), Spearman’s ρ between NGALds and effluent WCC = 0.82 (p < 0.01), Inter-operator reproducibility: ρ = 0.847 (p < 0.001), κ = 0.786 (p < 0.001). All peritonitis cases had NGALds ≥ 300 ng/mL (proposed cutoff) No formal sensitivity/specificity or AUC reported (preliminary study) | Domain 1: Patient selection: clear inclusion/exclusion; consecutive enrolment Domain 2: Index test: blinded operators; pre-specified cutoffs Domain 3: Reference standard: ISPD criteria with culture/WCC -Flow & timing: concurrent sampling for cases/controls Domain 4: Interpretation: objective readouts (dipstick categories; immunoassay thresholds) Overall risk: High |

| Virzì et al., 2024 [37], Italy | Retrospective analysis | Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis | - Total number of participants: 301 peritoneal effluent samples - Patient population: PD patients (healthy during routine analysis and with suspected/confirmed peritonitis) - Mean/median age: Not reported - Gender distribution: Not reported - Specific inclusion criteria: PD patients undergoing routine analysis or with suspected/confirmed peritonitis - Specific exclusion criteria: Not reported |

Type of assay: Two methods compared: NGALlab: BioPorto test (particle-enhanced turbidimetric immunoassay) NGALds: Rapid semi-quantitative colorimetric dipstick test - Specific kit or technology used: Antibody sandwich lateral flow dipstick test- NGAL measurement units: μg/L - Threshold values used for diagnosis: >100 μg/L for peritonitis diagnosis- Dipstick categories: 25, 50, 100, 150, 300, 600 μg/L |

Diagnosed by ISPD criteria for peritonitis | - Spearman’s Rs = 0.876 (p = 10⁻⁹⁶) - Sensitivity: 96 % (150/156) - Specificity, PPV, NPV, AUC: not reported |

- Domain 1: Patient Selection - Low risk (parallel samples from both healthy and peritonitis patients) - Domain 2: Index Test - Low risk (NGALds compared to established NGALlab) - Domain 3: Reference Standard - Low risk (NGALlab as reference) - Domain 4: Flow and Timing - Low risk (retrospective analysis with parallel samples) Overall risk: Moderate |

| Study (year) | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Overall certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al., 2023 | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Biomy et al., 2021 | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Chen et al., 2024 | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | High |

| Cullaro et al., 2017 | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Hassan et al., 2023 | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Khalil et al., 2023 | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Lippi et al., 2013 | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Liu et al., 2020 | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Martino et al., 2012 | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Martino et al., 2015 | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Morisi et al., 2024 | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Virzì et al., 2022 | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

| Virzì et al., 2024 | Moderate | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Undetected | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).