Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

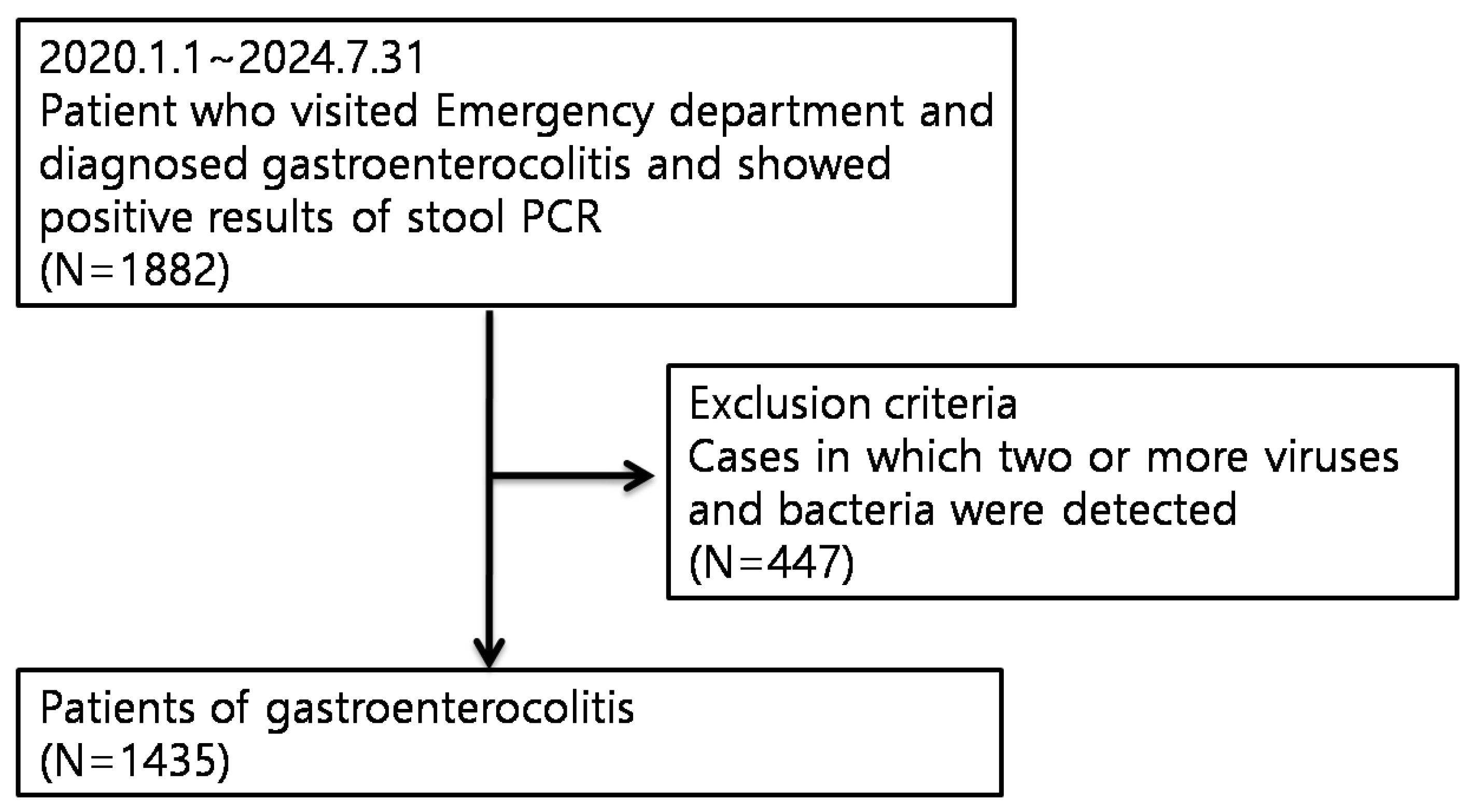

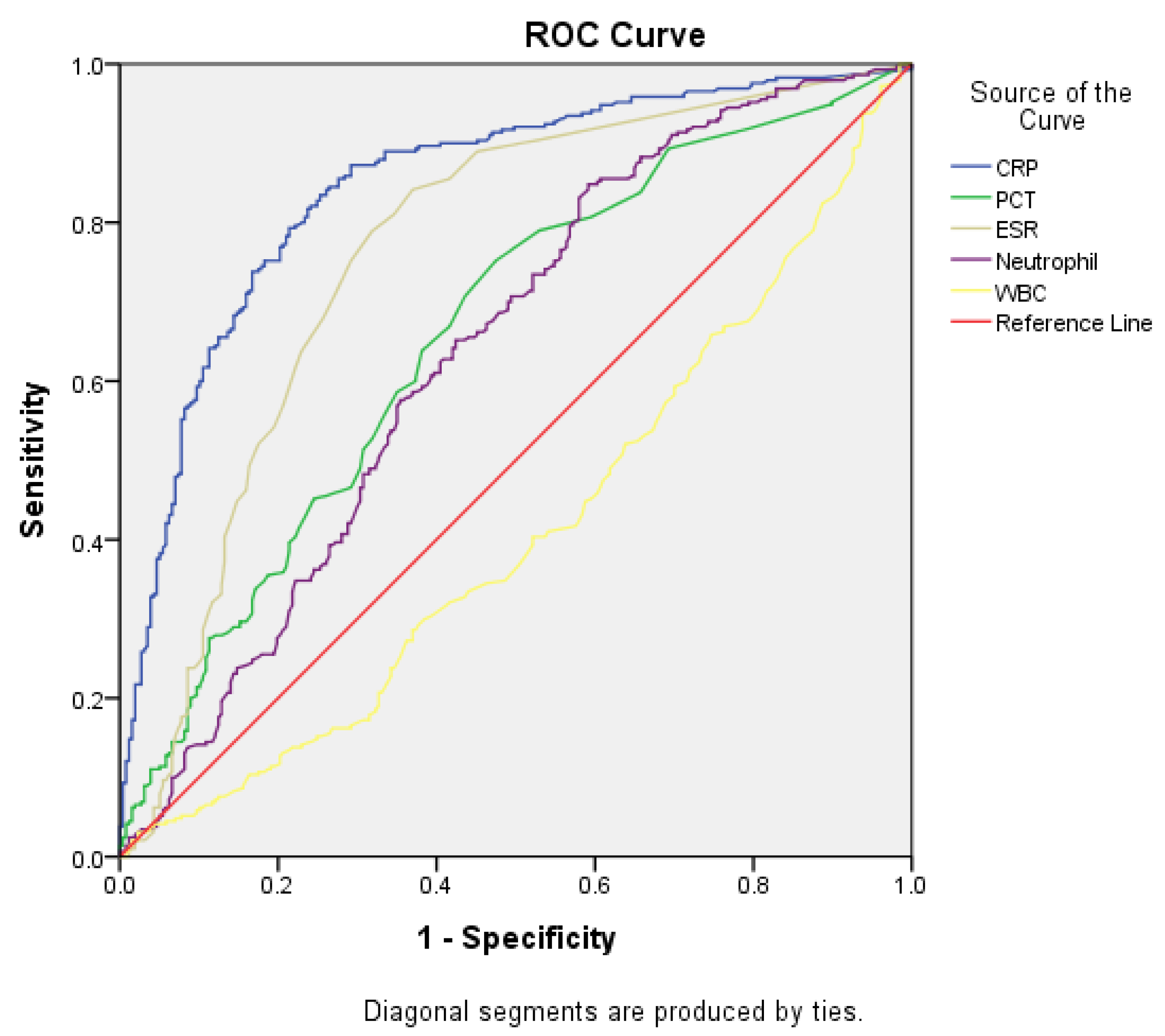

Background/Aim: Bacterial and viral gastroenteritis present with overlapping symptoms, including vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Stool tests have been used to differentiate between them; however, stool cultures are time-consuming and stool polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests are expensive. The role of the clinical value of procalcitonin (PCT) as a diagnostic marker of bacterial gastroenteritis remains to be investigated. This study evaluated the diagnostic value of PCT for the early diagnosis of bacterial gastroenteritis. Methods: The medical records of patients diagnosed with gastroenteritis by the emergency department with positive stool PCR results confirming the diagnosis between January 1, 2020, and July 31, 2024, were retrospectively reviewed. Demographic characteristics and laboratory findings, including the PCT and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, were analyzed. The area under the curve (AUC) for the diagnosis of bacterial gastroenteritis was assessed to determine the diagnostic potential of PCT. Results: Among the 1,882 cases identified, 1,435 met the inclusion criteria. CRP exhibited superior diagnostic performance for diagnosing bacterial gastroenteritis in general, with an AUC of 0.848 (95% CI, 0.815–0.881; p<0.001). However, in patients aged >17 years with fever (≥38°C), PCT was the only significant inflammatory marker, and the AUC of PCT was 0.767 (95% CI: 0.603–0.932; p=0.019). Conclusions: CRP is effective in predicting bacterial gastroenteritis; however, PCT may serve as a valuable biomarker for the early diagnosis of febrile adult patients. Further large-scale studies must be conducted to validate these results and improve diagnostic strategies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Laboratory Tests

2.3. Definition of Bacterial Gastroenteritis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Pathogen Detection

3.2. ROC Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Asy, H.M.; Gamal, R.M.; Albaset, A.M.A.; Elsanosy, M.G.; Mabrouk, M.M. New diagnostic biomarker in acute diarrhea due to bacterial infection in children. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med 2017, 4, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çetin, S.; Telli, E.; Şahin, A.M.; Uğur, M.; Aydın, E.; Şenel, İ.; Yetkin, M.A. Gastrointestinal PCR panel results and antibiotic use in acute gastroenteritis cases: how appropriate are we in our usage? Indian J Med Microbiol 2024, 47, 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, J. Procalcitonin. J Clin Pathol 2015, 68, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Jang, B.K.; Chung, W.J.; Cho, K.B.; Hwang, J.S. Diagnostic value of serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein in discriminating between bacterial and nonbacterial colitis: a retrospective study. J Yeungnam Med Sci 2023, 40, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.J.; Kang, S.H.; Moon, H.S.; Sung, J.K.; Jeong, H.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Joo, J.S.; Lee, E.S.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, B.S. Serum procalcitonin levels can be used to differentiate between inflammatory and non-inflammatory diarrhea in acute infectious diarrhea. Med (Baltim) 2018, 97, e11795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enguix-Armada, A.; Escobar-Conesa, R.; García-De La Torre, A.; De La Torre-Prados, M.V. Usefulness of several biomarkers in the management of septic patients: C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, presepsin and mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin. Clin Chem Lab Med 2016, 54, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klouche, K.; Cristol, J.P.; Devin, J.; Gilles, V.; Kuster, N.; Larcher, R.; et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of soluble CD14 subtype (Presepsin) for sepsis and community-acquired pneumonia in ICU patients. Ann Intensive Care 2016, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leli, C.; Ferranti, M.; Marrano, U.; Al Dhahab, Z.S.; Bozza, S.; Cenci, E.; Mencacci, A. Diagnostic accuracy of presepsin (sCD14-ST) and procalcitonin for prediction of bacteraemia and bacterial DNAaemia in patients with suspected sepsis. J Med Microbiol 2016, 65, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlovic, D.; Brkic, S.; Uvelin, A.; Draskovic, B.; Vrsajkov, V. Use of presepsin and procalcitonin for prediction of SeptiFast results in critically ill patients. J Crit Care 2017, 40, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diseases KSoI. Clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal infections. Infect Chemother 2010, 42, 323–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, S. Procalcitonin and the role of biomarkers in the diagnosis and management of sepsis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2012, 73, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, P.; Yu, F. Value of CRP, PCT, and NLR in prediction of severity and prognosis of patients with bloodstream infections and sepsis. Front Surg 2022, 9, 857218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iturriza-Gómara, M.; Cunliffe, N.A. Viral gastroenteritis. In Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Luaces, C.; Pou, J. Procalcitonina en la valoración del niño con fiebre sin foco. An Pediatr Continuada 2004, 2, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soreng, K.; Levy, H.R. Procalcitonin: an emerging biomarker of bacterial sepsis. Clin Microbiol Newsl 2011, 33, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covington, E.W.; Roberts, M.Z.; Dong, J. Procalcitonin monitoring as a guide for antimicrobial therapy: a review of current literature. Pharmacotherapy 2018, 38, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, I.; Fasih, A.; Wang, Y. The use of procalcitonin in the determination of severity of sepsis, patient outcomes and infection characteristics. PLOS One 2018, 13, e0206527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thia, K.T.-J.; Chan, E.S.-Y.; Ling, K.-L.; Ng, W.-Y.; Jacob, E.; Ooi, C.-J. Role of procalcitonin in infectious gastroenteritis and inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 2008, 53, 2960–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.-L.; Tseng, C.-P.; Tsay, P.-K.; Chang, S.-S.; Chiu, T.-F.; Chen, J.-C. Procalcitonin as a marker of bacterial infection in the emergency department: an observational study. Crit Care 2003, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, B.; Krüger, C.M.; Schilling, M.K. Procalcitonin: improved biochemical severity stratification and postoperative monitoring in severe abdominal inflammation and sepsis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2004, 389, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, R.; Kutz, A.; Mueller, B.; Schuetz, P. Procalcitonin-guided diagnosis and antibiotic stewardship revisited. BMC Med 2017, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, B.M.; Kemppainen, E.A.; Gumbs, A.A.; Büchler, M.W.; Wegscheider, K.; Bassi, C.; Puolakkainen, P.A.; Beger, H.G. Early assessment of pancreatic infections and overall prognosis in severe acute pancreatitis by procalcitonin (PCT): a prospective international multicenter study. Ann Surg 2007, 245, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofidi, R.; Suttie, S.A.; Patil, P.V.; Ogston, S.; Parks, R.W. The value of procalcitonin at predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis and development of infected pancreatic necrosis: systematic review. Surgery 2009, 146, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisner, M.; Rauschmayer, C.; Schmidt, J.; Feyrer, R.; Cesnjevar, R.; Bredle, D.; Tschaikowsky, K. Early increase of procalcitonin after cardiovascular surgery in patients with postoperative complications. Intensive Care Med 2002, 28, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paruk, F.; Chausse, J.M. Monitoring the post surgery inflammatory host response. J Emerg Crit Care Med 2019, 3, 47–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bele, N.; Darmon, M.; Coquet, I.; Feugeas, J.-P.; Legriel, S.; Adaoui, N.; Schlemmer, B.; Azoulay, E. Diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin in critically ill immunocompromised patients. BMC Infect Dis 2011, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Ma, X.; Ai, Y. Diagnostic value of serum procalcitonin for infection in the immunocompromised critically ill patients with suspected infection. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2015, 27, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancella de Abreu, M.; Cassard, C.; Cherubini, I.; Houas, E.; Dechartres, A.; Hausfater, P. Usefulness of serum procalcitonin and point-of-care multiplex PCR gastro-intestinal panel in acute diarrhoea or colitis in the emergency department. Biomarkers 2023, 28, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, R.R.; Lemonovich, T.L. Serum procalcitonin in the diagnosis and management of intra-abdominal infections. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther 2012, 10, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, P.; Chiappa, V.; Briel, M.; Greenwald, J.L. Procalcitonin algorithms for antibiotic therapy decisions: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and recommendations for clinical algorithms. Arch Intern Med 2011, 171, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, T.G.; Olortegui, M.P.; Kosek, M.N. Viral gastroenteritis. Lancet 2024, 403, 862–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.L.; Snider, R.; Nylen, E.S. Procalcitonin assay in systemic inflammation, infection, and sepsis: clinical utility and limitations. Crit Care Med 2008, 36, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, D.S.; Friedmann, R.; Husseini, A.; Ivgi, H.; Yinnon, A.M.; Assous, M.V. Can procalcitonin contribute to the diagnosis of Clostridium difficile colitis? Isr Med Assoc J 2017, 19, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Bacterial gastroenteritis | Viral gastroenteritis | p-value |

| (n=849) | (n=586) | ||

| Age (year, mean ± SD) | 35.71±29.10 | 13.13±23.87 | <0.001 |

| Male sex (n, %) | 473 (55.7%) | 302 (51.5%) | <0.001 |

| Symptom | |||

| Fever (BT ≥38°C) | 492 (62.4%) | 174 (31.6%) | <0.001 |

| Abdominal pain (n, %) | 582 (90.5%) | 179 (73.4%) | <0.001 |

| Nausea (n, %) | 352 (55.7%) | 409 (80.7%) | <0.001 |

| Vomiting (n, %) | 221 (35.2%) | 403 (78.9%) | <0.001 |

| Diarrhea (n, %) | 712 (88.1%) | 319 (61.1%) | <0.001 |

| Blood in stool (n, %) | 62 (7.6%) | 15 (2.9%) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory finding | |||

| WBC count (×103/μL) | 10421.77±4977.77 | 11900.05±5679.06 | <0.001 |

| Neutrophil count (%) | 74.52±14.27 | 63.32±21.99 | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 8.28±7.24 | 1.68±3.57 | <0.001 |

| ESR (mg/dL) | 22.34±16.80 | 11.43±16.36 | <0.001 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 1.72±10.61 | 0.34±0.96 | <0.001 |

| Underlying disease | |||

| DM | 79 (9.3%) | 21 (3.6%) | <0.001 |

| Thyroid disease | 11 (1.3%) | 4 (0.7%) | 0.262 |

| HTN | 142 (16.7%) | 32 (5.5%) | <0.001 |

| CVD | 25 (2.9%) | 7 (1.2%) | 0.027 |

| Respiratory disease | 7 (0.8%) | 3 (0.5%) | 0.484 |

| Liver disease | 4 (0.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0.342 |

| Renal disease | 17 (2.0%) | 3 (0.5%) | 0.018 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 80 (9.4%) | 14 (2.4%) | <0.001 |

| Surgical history | 24 (2.8%) | 9 (1.5%) | 0.273 |

| BT, body temperature; WBC, white blood cell; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; | |||

| DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; CVD, cerebrovascular disease. | |||

| Type | Data |

|---|---|

| Campylobacter spp. | 490 (57.7%) |

| Clostridioides difficile toxin A/B | 80 (9.4%) |

| EAEC (Enteroaggregative E. coli) | 5 (0.6%) |

| EPEC (Enteropathogenic E. coli) | 16 (1.9%) |

| ETEC (Enterotoxigenic E. coli) | 11 (1.3%) |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides | 10 (1.2%) |

| Salmonella spp. | 165 (19.4%) |

| Shigella spp. | 3 (0.4%) |

| STEC (Shiga-like toxin-producing E. coli) stx1/stx2 |

35 (4.1%) |

| Vibrio spp. | 11 (1.3%) |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | 23 (2.7%) |

| Total | 849 (100.0%) |

| Type | Data |

|---|---|

| Adenovirus 40/41 | 61 (10.4%) |

| Astrovirus | 53 (9.0%) |

| Norovirus GI/GII | 325 (55.5%) |

| Rotavirus | 86 (14.7%) |

| Sapovirus | 61 (10.4%) |

| Total | 586 (100.0%) |

| Index | AUC (95% CI) | Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP | 0.848 (0.815–0.881) | 1.8 | 79.0% | 78.6% | <.0001 |

| PCT | 0.660 (0.614–0.706) | 0.1 | 60.3% | 62.6% | <.0001 |

| ESR | 0.763 (0.721–0.805) | 10.5 | 71.0% | 72.8% | <.0001 |

| Neutrophil count | 0.638 (0.591–0.684) | 74.4 | 60.7% | 67.0% | <.0001 |

| WBC | 0.412 (0.364–0.460) | 10750 | 41.7% | 42.4% | <.0001 |

| CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; WBC, white blood cell; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval. | |||||

| Index | AUC (95% CI) | Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP | 0.715 (0.479–0.951) | 8.98 | 63.4% | 71.4% | 0.059 |

| PCT | 0.767 (0.603–0.932) | 0.1 | 68.8% | 71.4% | 0.019 |

| ESR | 0.683 (0.396–0.970) | 13.5 | 71.0% | 71.4% | 0.108 |

| Neutrophil count | 0.445 (0.178–0.713) | 84.4 | 41.9% | 42.9% | 0.632 |

| WBC | 0.510 (0.269–0.751) | 10500 | 41.9% | 42.9% | 0.930 |

| CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; WBC, white blood cell; BT, body temperature; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval. | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).