1. Introduction

There is emerging interest and research investigating the relationship between daily stressors, mood, anxiety, and sleep quality. Poor mood and anxiety are often considered independently, however, a systematic review determined robust and consistent evidence of comorbidity between broadly defined mood and anxiety disorders [

1]. Epidemiological studies show that sleep disturbances, particularly insomnia, affect roughly half of those coping with anxiety, and that poor sleep can function to initiate or further exacerbate it [

2]. While interest extends throughout adulthood, younger adults are experiencing anxiety and mood issues more significantly than previous generations. A recent study looked at the prevalence of anxiety and/or depression symptoms in 2,809 young adults aged 18-25 years. Nearly 50% of young adults experienced mental health symptoms during a global pandemic. Of those experiencing symptoms, 39% had reported using prescription medications and/or had received mental health support, while 36% reported they were unable to access mental health counseling [

3]. Reduced availability to mental health support services and/or medications, the search for more natural, plant-based solutions continues to gain consumer interest.

Improved sleep and mood may enhance emotional regulation and stress resilience, potentially facilitating the development of intimacy and the successful navigation of this psychosocial stage [

4]. Young adults who participated in nine years of longitudinal sleep research showed significantly reduced sleep quantity and quality [

5]. The relationship between young adults' usage of social media and sleep disruptions was also examined in a study involving 1788 US young adults between the ages of 19 and 32. According to research data extrapolated, there was a significantly larger likelihood of suffering sleep problems, such as trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or experiencing restful sleep, while using social media more frequently and in greater volume [

5]. There is a recognized need for healthier sleep solutions in this age group, along with growing interest in plant-based remedies to help improve both sleep quantity and quality.

Cortisol plays a central role in the body's stress response and has been widely studied as a biomarker linking psychological and physiological health. Cortisol is a stress marker for the body and levels typically increase in response to physical or psychological stress. Poor mood and anxiety are often associated with dysregulation of cortisol. More specifically, hypercortisolemia may be attributed to a dysfunction of glucocorticoid-receptor-mediated negative feedback mechanisms within the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, which in turn can play a pivotal role in mood disorders, characterized by depressive symptoms and cognitive deficits [

6]. Higher salivary cortisol levels can indicate elevated stress and irregular cortisol patterns reflecting possible disruptions in circadian rhythms and/or sleep issues.

Individual or blended mushroom components, extracts, and concentrates have been used in traditional medicines and applied to address conditions related to cognition, mood, and sleep [

7,

10]. Different mushroom species vary in the presence and concentrations of bioactive compounds that can directly or indirectly affect cognition, mood, and sleep, including vitamins, beta glucans (β-glucans), terpenoids, diterpenoids, polyphenols, and sterols [

7,

10]. Mushroom polysaccharides are of differing chemical composition, the majority being beta-glucans; these have beta linkages (1 to >3) in the primary chain of glucan and subsequent beta branch points (1 to >6) which are required for their biological action [

11].

Some mushrooms, typically phenolics or tetracyclic triterpenoids/steroids, are considered adaptogens, purported to support managing typical life stressors [

8,

9]. Adaptogens are naturally occurring bioactive compounds found in whole mushrooms and mushroom extracts consisting usually of either complex plant phenolics or tetracyclic triterpenoids/steroids classified by their relation to a physiological process, notably adaptation to environmental challenges that support resistance to life stressors by modulating or regulating the cortisol response [

7,

8,

9].

For instance,

Ganoderma lucidum is a fungus commonly known as Lingzhi or Reishi and is reported to have analgesic, and sedative potential as well as reduce fatigue and states of sadness, which in turn can affect mood [

12,

13] In Traditional Chinese Medicine, Reishi mushroom is esteemed for its ability to soothe the mind and promote relaxation, effects attributed to its adaptogenic properties and the presence of triterpenes [

14]. Reishi is also traditionally recognized for its ability to calm the mind and restore balance to the body [

15]. Its adaptogenic activity is attributed to a diverse array of bioactive compounds, notably triterpenes, specifically ganoderic acids, which exhibit a molecular structure similar to steroid hormones [

14]. Reishi also contains biologically active polysaccharides and over 200 other constituents, many of which are among the most pharmacologically active identified in natural sources [

14,

16]. Meanwhile, components of

Cordyceps militaris have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, and its application is associated with mood [

17]. Moreover, the

Cordyceps genus, inclusive of species

militaris and

sinesis, are characterized by numerous bioactive compounds including unique cyclodepsipeptides, nucleosides, and polysaccharides which may play a role in supporting cognition and more desirable mood states [

18,

19,

20]. These effects have also been attributed to the presence of cordycepin, adenosine, ergosterol, and multiple amino acids [

21]. At the same time, there is growing interest in

Hericium erinaceus (Lion’s Mane) for its potential neuroprotective and neuro-regenerative properties [

22,

23]. Lion’s Mane shows promise for more immediate application related to mood, stress, and states of worry improvement [

24]. It has been increasingly studied for the potential to support cognitive function, neurological health, and mood regulation [

25]. Supplementation of Lion’s Mane was reported to improve some measures of cognitive function, perceived stress and mood in young adults (ages 18-45) [

26].

Delivery form is another important aspect of dietary supplementation when considering regulatory approval, ingredient interactions, bioactive stability, bioavailability, etc. Traditionally, botanical-based dietary supplements have mostly been marketed in pill form (e.g. capsules, tablets, soft gels, etc.) and secondarily ready-to-mix powders. Variety and lifestyle application is a key consideration, and many people look for alternative delivery forms of dietary supplementation. For instance, mushroom ingredients have been explored as an option for coffee [

27]. Meanwhile, functional bar formats can offer advantages related to delivering additional nutrients as well as sensory properties that may overcome flavor masking challenges associated with many botanical ingredients including mushrooms [

28,

29].

There is widespread anxiety, disturbed mood, and sleep disruption in young adults. There is an ongoing quest for more natural remedies for these conditions. Considering these aspects, the primary purposes of this investigation were to evaluate the efficacy of a commercially available proprietary organic, standardized mushroom blend, either as capsules or part of a functional bar on mood, sleep quality, and duration, and salivary cortisol levels. We hypothesized that 25-day supplementation with MB would improve mood states of depression, anxiety, and stress compared to placebo in young adults as a result of secondary improvements expected in sleep quality and salivary cortisol levels.

2. Materials and Methods

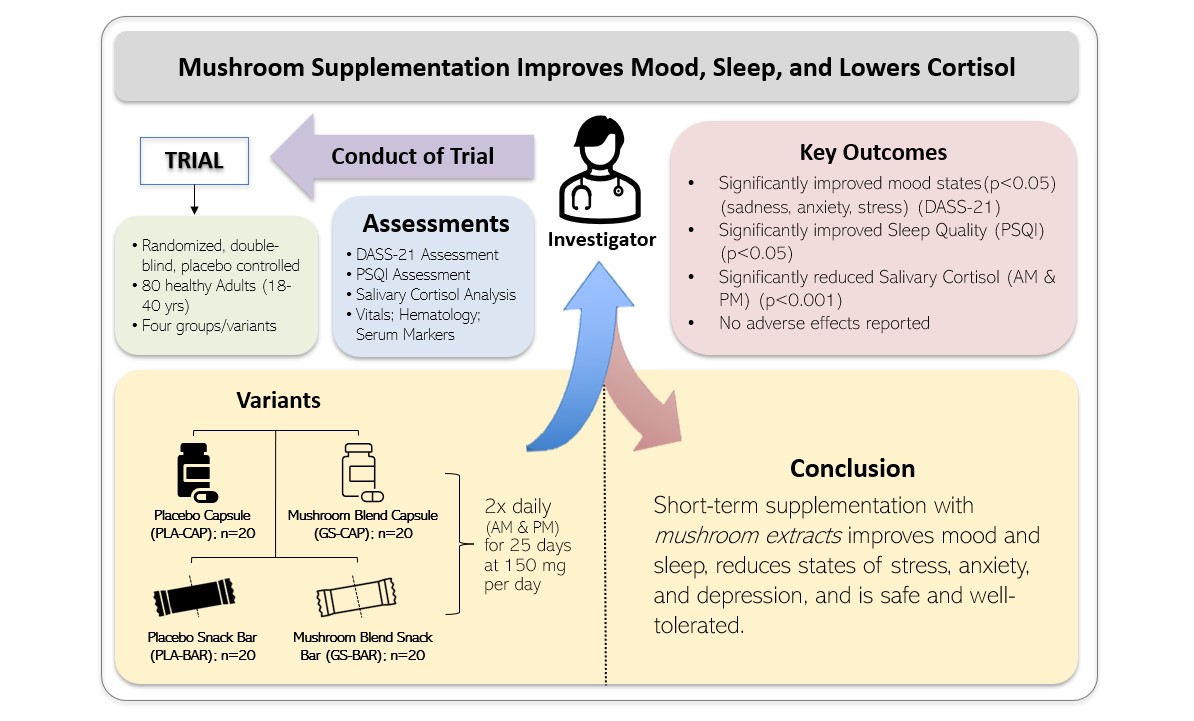

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted by BioAgile Therapeutics Pvt. Ltd. at Sri B.M. Patil Medical College Hospital in Vijayapura, Karnataka, India. The study was designed to evaluate the effects of an organic mushroom extract blend (MB) of Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi mushroom), Cordyceps militaris, Hericium erinaceus (Lion’s Mane), and fermented Cordyceps Sinesis on mood, sleep quality, and salivary cortisol levels in healthy young adults. The protocol received approval from the hospital’s Institutional Ethics Committee, and the trial was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry – India (CTRI/2024/02/063100). Participants and the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination of this research.

2.1. Participants

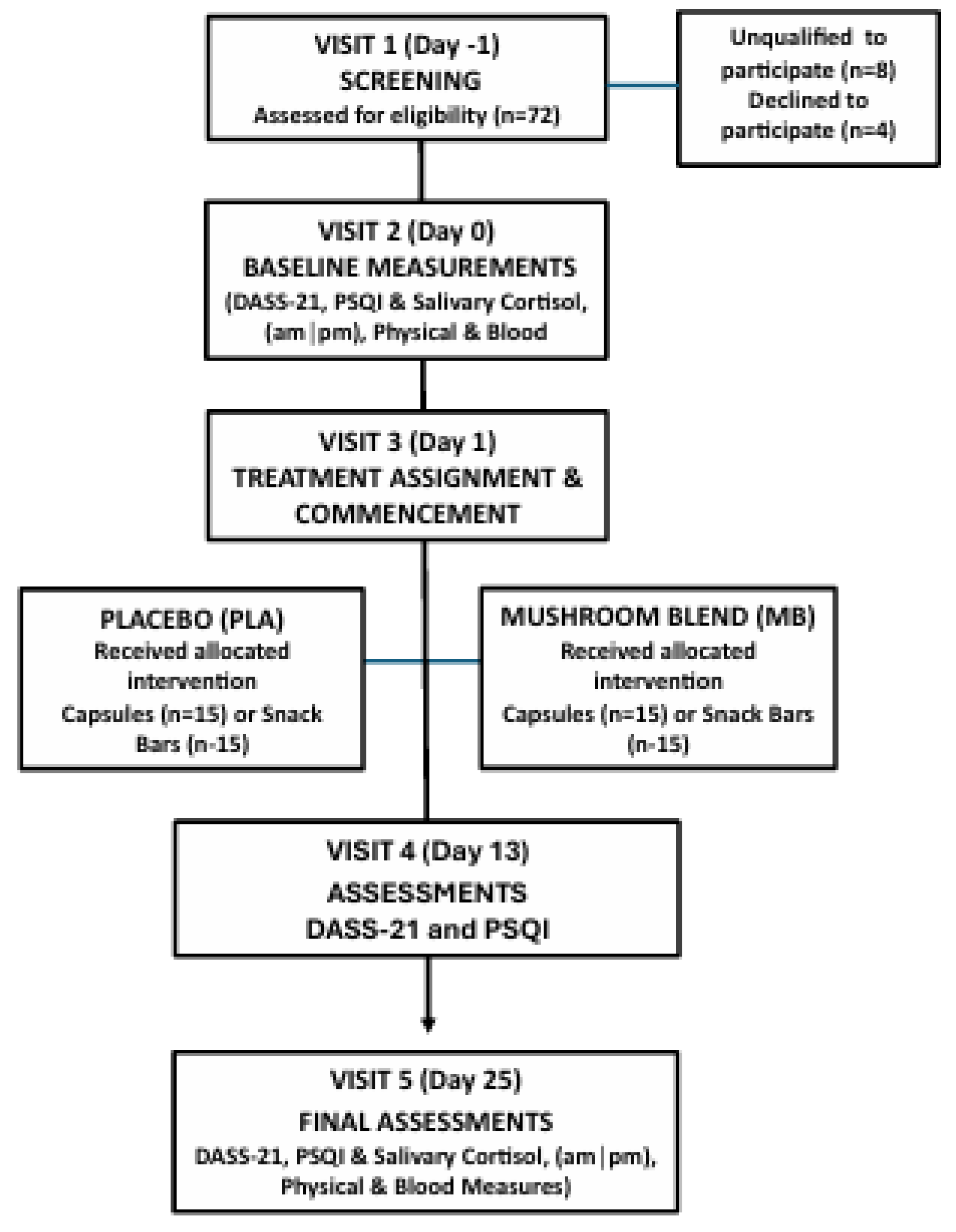

A total of 80 men and women between the ages of 18 and 40 were enrolled and randomly assigned to one of four groups (n = 20 per group): placebo capsule (PLA-CAP), placebo functional snack bar (PLA-BAR), organic mushroom extract blend capsule (MB-CAP), or organic mushroom extract blend functional bar (MB-BAR). Each group received their assigned intervention twice daily, once in the morning (with or without food) and once in the evening (with or without food), for a period of 25 days. The experimental design and treatment allocation are shown in

Figure 1, and demographic characteristics of the study population are presented in

Table 1. Assessments were performed at baseline (Day 0), Day 13, and at study completion (Day 25), focusing primarily on the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales-21 psychological questionnaire (DASS-21), and validated with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire and salivary cortisol analysis. Other outcomes included vital signs, and hematological and liver integrity analysis for safety parameter assessment.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria included experiencing feelings of fatigue, weakness and/or tiredness, moodiness, irritability and/or restlessness. Additional inclusion criteria comprise chronic lack of concentration, fear and/or worry, difficulty completing tasks and/or lack of motivation, loneliness and/or withdrawal from or lack of interest in social groups. Inclusion criteria for sleep disturbances included changes in sleeping patterns or habits and chronic difficulty falling or staying asleep, daily grogginess.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Individuals were excluded from participation if they had been using antidepressant medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), or any central nervous system depressants, including benzodiazepines, barbiturates, beta blockers, opioids, or recreational substances like cannabis. Use of tobacco products, including vaping devices, also disqualified participants. Individuals with diagnosed diabetes or pre-diabetic conditions were excluded due to potential metabolic variability and risk of glycemic instability. Additional exclusions applied to those who were pregnant or breastfeeding, or who had known allergies to mushrooms or mushroom-derived ingredients. No concomitant treatments or supplements affecting mood, sleep, or cortisol were permitted during the trial, and participants were instructed to maintain their usual diet and activity levels. Primary emphasis was placed on ruling out participants whose current medications, metabolic status, psychiatric history, or physiological state could interfere with the study outcomes or pose safety concerns. Final eligibility was confirmed by the Principal Investigator.

2.4. Dietary Ingredient Supplementation

This was a parallel-group, four-arm clinical trial in which participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1:1 ratio using block randomization. The allocation sequence was implemented using sealed opaque envelopes prepared by the Contract Research Organization (CRO) in consultation with a statistician, and envelopes were opened at Visit 3 (Day 1) to assign participants. To maintain double-blind conditions, active and placebo capsules were matched in size, shape, color, and texture, and were dispensed in sealed bottles that were identical in appearance and labeling. Similarly, active and placebo chewable snack bars were made using the same base formulation and individually wrapped in visually identical packaging.

Participants received either a capsule or a functional snack bar, which was to be consumed twice daily (morning and early evening). Capsules were vegetarian compatible (hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC)) utilizing maltodextrin as an excipient. Participants in CAP groups consumed 1 capsule twice daily. Snack bars (BAR) were prepared with/without MB and were 25 grams per bar consumed twice daily. See

Table 2 for composition details for both capsules and bars. Participants were instructed to avoid initiating any new medications, supplements, or treatments during the trial period. No concomitant care was reported during the study. Compliance was tracked through a combination of returned product counts and participant-reported use via a designated field worker. According to study records, all products were taken as directed, and no deviations from the protocol were noted.

2.5. Organic Mushroom Blend:

Organic mushroom extract blend (distributed by NURA USA, ADAPTGUARD®) consists of organic Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi) fruiting body extract, organic Cordyceps militaris fruiting body extract, organic Hericium erinaceus (Lion’s Mane) fruiting body extract, and fermented Cordyceps sinesis mycelium extract. This is a full-spectrum blend with a minimum of 28% beta glucans. The total daily intake of the mushroom extract blend was 250 milligrams, split between morning and evening supplementation of 125 milligrams each time and provided as a snack bar or in capsule form. Additional documentation regarding the mushroom extract blend, including the manufacturer’s specification sheet and certificate of analysis, is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

2.6. Allocation Concealment

Participants and scientists were blinded to treatments until completion of the study. Allocation concealment was ensured through secure storage of randomization codes in tamper-evident envelopes, and a master randomization chart was sealed and stored in both physical and secure electronic formats. Unblinding was permitted only under specific conditions, such as medical emergencies or serious adverse events, and could only be performed by authorized personnel not involved in the day-to-day management of the trial.

2.7. Assessments

DASS-21 - The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales-21 items (DASS-21) report is a psychological questionnaire that was used to measure the dimensions of depression, anxiety, and stress [

30]. The DASS-21 psychological questionnaire was administered at the testing site at baseline (Day 0), Day 13, and final assessment (Day 25).

PSQI - The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire is commonly used in both clinical and research settings to assess several aspects of sleep quantity and quality, including sleep duration, sleep disturbances, and overall sleep satisfaction [

31]. The PSQI was surveyed at the test site at baseline (Day 0), Day 13, and final assessment (Day 25).

Salivary Cortisol - Salivary cortisol was tested in the morning and evening at baseline (Day 0) and final assessment (Day 25). Saliva samples were collected in test tubes at the testing site by the authorized field worker, stored accordingly, and analyzed on site. Cortisol is often measured as an indicator of mood states of sadness, anxiousness, and other stress-related conditions during clinical research.

2.8. Physical Assessments

Individual height and weight were measured by standing stadiometer and balance scale. Oral temperature was assessed as average of three measures per participant via calibrated thermometer and average measure was used. The heart rate, as beats per minute (bpm), was measured three times by radial artery, each separated by one minute of comfortable rest in a cushion-bottom, back supported chair with feet flat and legs uncrossed on an adjustable height platform and without pressure under knee joint. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were assessed in triplicate with 1-minute rested intervals immediately after heart rate assessment set utilizing an automated upper-arm pressure cuff.

2.9. Hematology Assessment

Following physical assessments, blood was captured via antecubital fossa vein or median cephalic and median basilic veins per professional assessment. Samples were assessed for red and white blood cell measures including Basophils (%), Eosinophils (%), Hemoglobin (gram/deciliter), Lymphocytes (%), Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (Pg), Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (Pg), Mean Corpuscular Volume (fL), Monocytes (%), Neutrophils (%), PCV (%), Platelet Count (Lakhs/cubic mm), Red Blood Cell Count (millions/cubic mm) and White Blood Cell Count (millions/cubic mm) at baseline (Day 0) and final assessment (Day 25).

2.10. Liver Integrity and Function Assessment

Addition to hematology measures above, liver enzyme levels tests, namely Alanine Transaminase (ALT/SGPT) (IU/I) and Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST/SGOT) (IU/I), as well as Serum Creatinine (mg/dl) were determined at baseline (Day 0) and final assessment (Day 25).

2.11. Statistical Assessment

Data entry and statistics were completed using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism 10. Normality was tested using D’Agiston and Pearson (K2) and Shapiro Wilk (W) tests. Based on that outcome, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied to compare baseline values with follow-up (Day 13 and Day 25) within each group for DASS-21 scores, PSQI scores, and salivary cortisol. The alpha priori was set at 0.05 (p<0.05). The efficacy evaluation included all participants who were randomized and completed at least one assessment following baseline. Participants were evaluated within the groups they were originally randomized to, preserving the structure of the trial design. The dataset used for final analysis included only the data collected. No values were estimated or imputed. The statistical approach was defined in advance in the study protocol and centered on assessing changes in mood, sleep quality, and salivary cortisol. A total sample size of 80 participants (n = 20 per group) was selected based on feasibility for a pilot randomized controlled trial and consistency with sample sizes used in similar investigative studies assessing mood, sleep, and stress outcomes. This size was considered adequate to detect a moderate effect, and to estimate variability for future confirmatory trials. For this study, no additional subgroup or sensitivity analyses were conducted, as they were not pre-specified in the registered protocol, the sample size was not powered for such analyses and performing them could have increased the risk of Type I error and generated potentially misleading results. No interim analyses or stopping guidelines were planned or implemented for this study, as it was a short-term pilot trial without predefined criteria for early stopping. Two participants (one from GS-BAR and one from PLA-BAR) withdrew before study completion due to personal reasons and were excluded from the final Day 25 analysis. No adverse events were reported.

3. Results

3.1. DASS-21 Score (Mood)

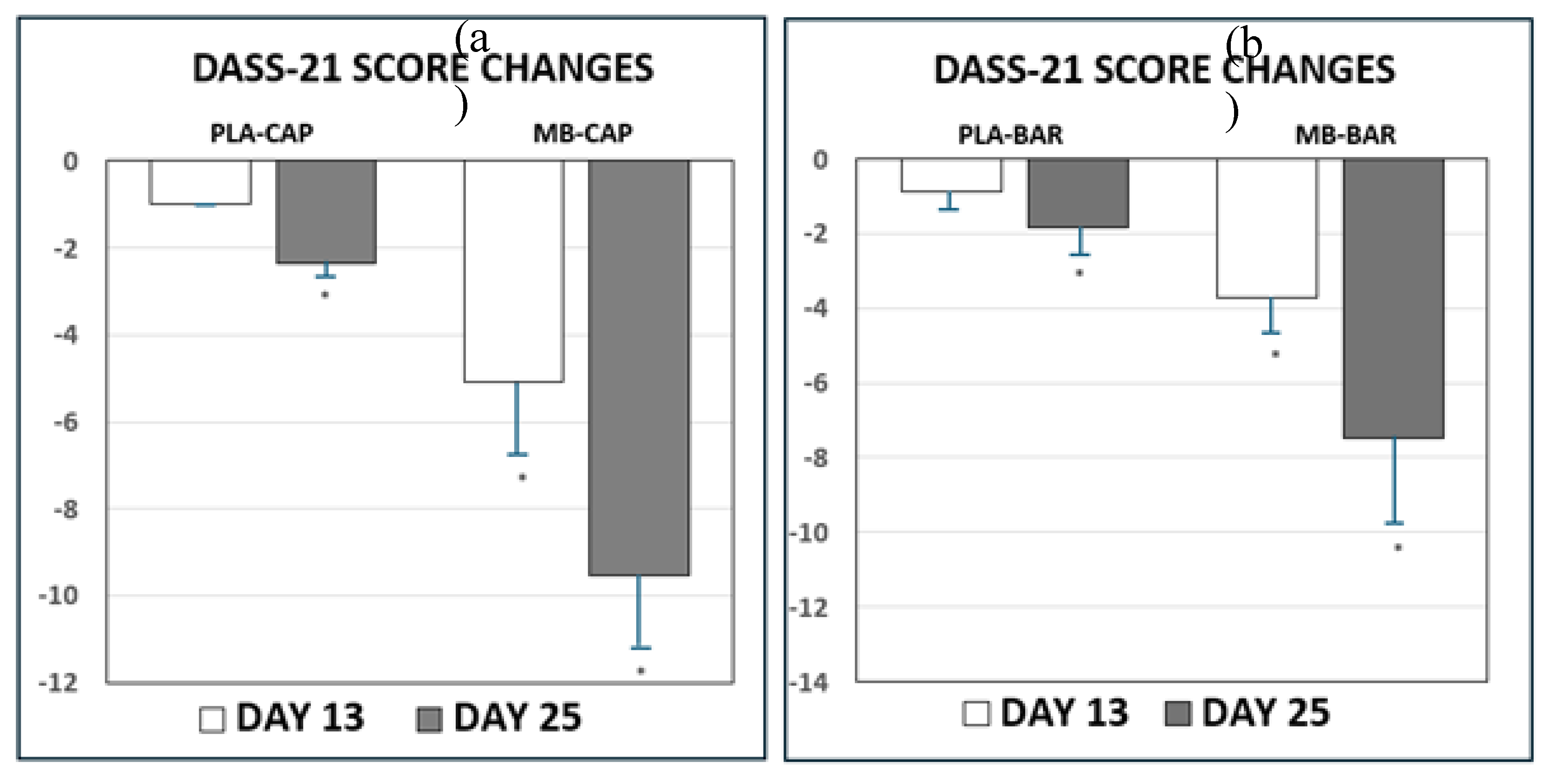

Table 3 and

Figure 2 presents scores and changes in DASS-21 scores from baseline (Day 0), Day 13, and final assessment (Day 25) of treatment. Participants were randomized to treatment arms to minimize bias and distribute potential confounding variables. Despite randomization, some baseline differences in DASS-21 scores were observed between groups, which can occur by chance, particularly in modestly sized samples. Significant improvements (p<0.05) in mood states of sadness, anxiousness, and stress were determined between baseline survey (Day 0), Day 13, and final assessment (Day 25) for both MB treatment groups. The scores and changes in DASS-21 scores with the organic mushroom extract treatment in both delivery forms were different from both PLA treatments. All treatments were observed to change from baseline (Day 0) to final assessment (Day 25) with the changes of the MB treatment groups being significantly greater than the changes for the PLA treatments in both applications.

3.2. Sleep Quality – PSQI

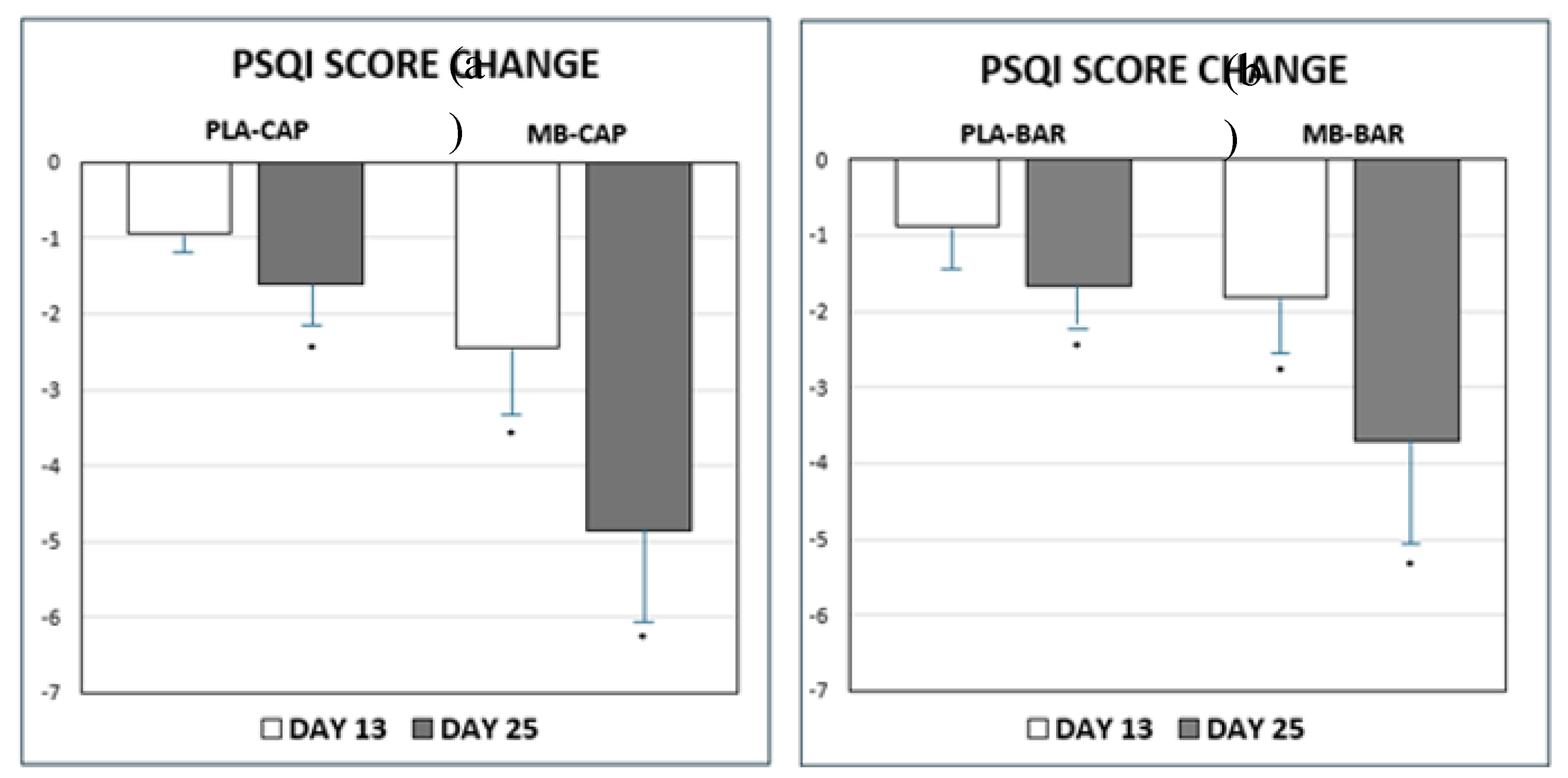

Despite random assignment baseline PSQI scores differed across treatment groups, with notably higher scores in the MB-CAP and MB-BAR groups. These differences are likely attributable to random variation, which can occur in modestly sized samples. To account for this, change-from-baseline analyses were performed and presented. There was a significant change in PSQI Score from baseline to post-baseline visits as presented in

Table 4 and

Figure 3. Higher PSQI scores indicate more severe sleep problems. Lower PSQI scores indicate improvements in sleep quality. Participants experienced a statistically significant improvement in overall sleep quality as results showed by reducing PSQI scores recorded with either MB-CAP and MB-BAR treatments consumed versus PLA of the same forms at Day 13 and final assessment (Day 25). All treatments showed changes from baseline (Day 0) to the final assessment (Day 25); however, the changes observed in the MB treatment groups were significantly greater than those in the PLA groups across both applications.

3.3. Salivary Cortisol

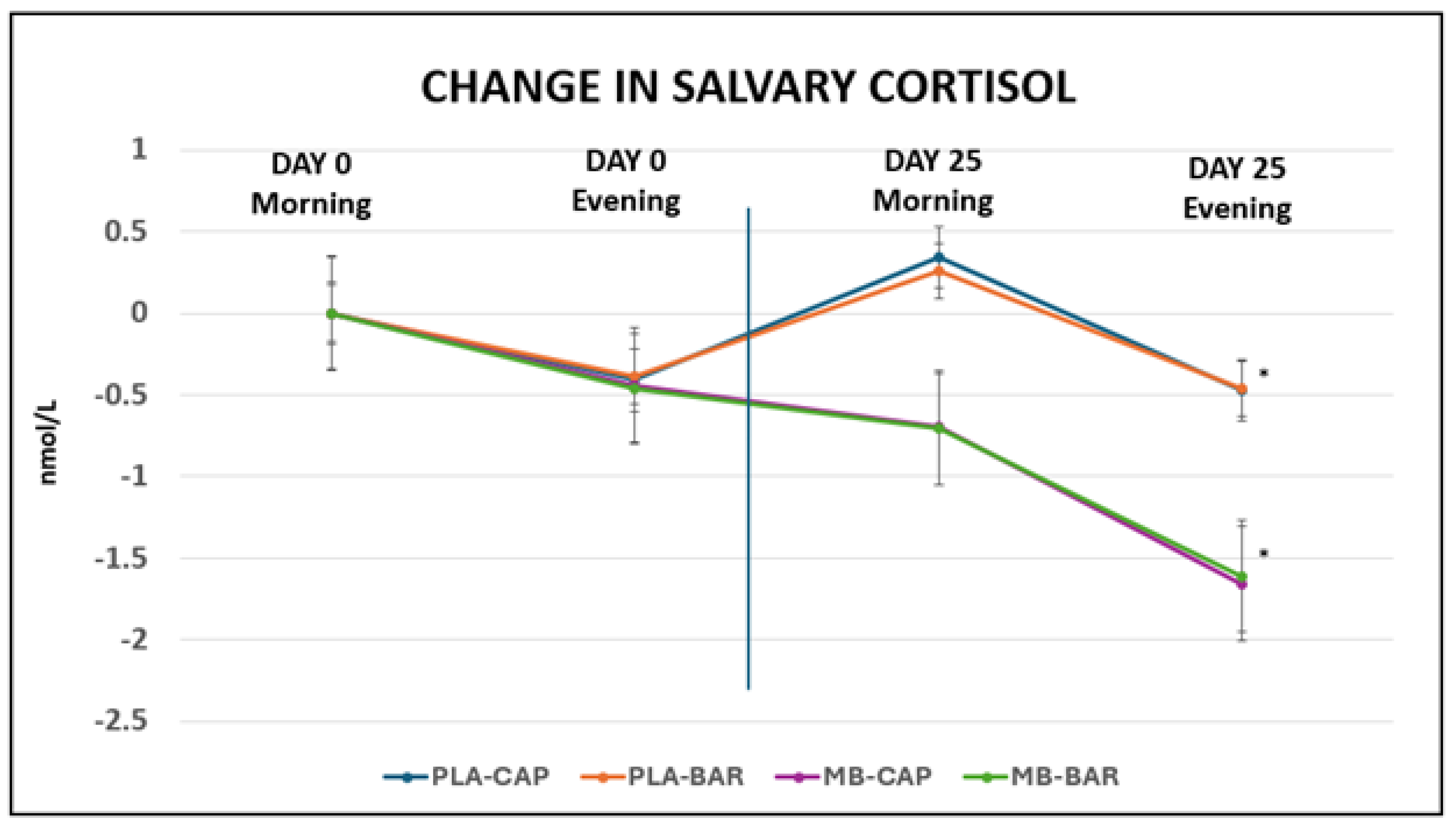

As presented in

Table 5 and

Figure 4, no significant differences were determined between morning and evening measures on Day 0 for any of the groups. Meanwhile, significant reductions (p<0.001) in salivary cortisol were determined between baseline (Day 0) and final assessment (Day 25) for both PLA and MB treatments of both forms at the time of day. MB treatment groups were significantly greater in change in salivary cortisol than the changes for the PLA treatments in both applications. These changes aligned with improvements in mood as assessed by DASS-21 on final assessment (Day 25). Although participants were randomized to treatment groups, baseline salivary cortisol levels varied across conditions. The MB-CAP group exhibited higher baseline cortisol levels than other arms, which may reflect random variation due to sample size and individual variability in physiological stress responses. Such differences are not uncommon in randomized trials, especially when sample sizes are modest.

3.4. Oral Temperature, Heart Rate and Blood Pressure Measures.

The results of baseline (Day 0) and final assessments (Day 25) for oral temperature, heart rate, blood pressures are presented in

Table 6. There were no significant differences that were determined in the change in oral temperature, heart rate and blood pressure measures from baseline (Day 0) to final assessments (Day 25) and are considered supportive of short-term tolerance and general safety.

3.5. Hematology & Serum Enzymes and Creatinine

The results of baseline (Day 0) and final assessments (Day 25) for hematology measures of red and white blood integrity and status are presented in

Table 7 and

Table 8. In addition, no significant differences were determined in the change in hematology and serum liver enzymes and creatinine from baseline (Day 0) to final assessments (Day 25) and are considered supportive of short-term tolerance and general safety.

4. Discussion

The present clinical trial evaluated the effects of a 25-day intervention with a proprietary organic mushroom blend (MB) delivered in either capsule or nutrition bar form on mood, sleep, and stress-related biomarkers in healthy adults. In addition to assessing efficacy, the study included a broad evaluation of clinical safety markers to establish short-term tolerability. The experimental design of this investigation is unique in that it provided time-course comparison within the treatment groups compared to placebo, and allowed for insight into different delivery forms, either capsules or snack bar. The results of the present investigation suggest that the specific organic mushroom blend utilized can have a general positive impact on sleep quality influencing mood states of sadness, stress, and anxiety.

4.1. Mood Improvements

Despite some baseline differences in DASS-21 scores due to the modestly sized trial, the organic mushroom blend was associated with statistically significant improvements in mood states, including reductions in sadness, anxiousness, and stress. Both delivery formats (capsule and bar) produced meaningful improvements by Day 13, which were sustained or enhanced by Day 25. Importantly, while all groups demonstrated some degree of mood improvement over time the degree of change in both MB groups was significantly greater than in the placebo controls. This suggests a treatment-specific benefit that may reflect the bioactive compounds in the mushroom blend, such as adaptogenic polysaccharides, triterpenes, or other neuroactive constituents previously linked to modulation of the HPA axis [

32].

4.2. Sleep Quality Enhancements

Sleep quality also improved significantly in the MB treatment arms compared to placebo as measured by the PSQI questionnaire. Notably, the MB-CAP and MB-BAR groups began the trial with higher baseline PSQI scores, indicating poorer initial sleep quality. However, both groups experienced marked reductions in PSQI scores by Day 13, with further improvements by Day 25, suggesting rapid and sustained benefits. These results are consistent with emerging evidence that certain medicinal mushrooms may influence sleep experiences and subjective sleep quality via modulation of neurotransmitters such as GABA and serotonin, or through indirect effects on stress reactivity and inflammation [

9,

33,

34,

35].

4.3. Salivary Cortisol Reductions

Reductions in salivary cortisol levels observed in this study further support the stress-relieving potential of the mushroom blend. While all treatment groups demonstrated significant decreases in both morning and evening cortisol by Day 25, the magnitude of change was notably greater in the MB treatment groups. These physiological changes parallel the improvements observed in DASS-21 scores, suggesting a coherent relationship between reduced cortisol output and improvements in mood and perceived stress. Although some baseline differences in cortisol levels were observed, variability is not uncommon in stress biomarker studies and likely reflects individual differences in HPA axis activity rather than a flaw in study design. Importantly, previous research validates the use of cortisol as a meaningful biomarker by establishing its predictable diurnal rhythm, with levels typically peaking in the early morning and declining throughout the day [

36]. This rhythm plays a regulatory role in many physiological systems, including the sleep-wake cycle, stress reactivity, and immune function, thereby reinforcing the biological relevance of monitoring salivary cortisol in the current study. While the relationship between cortisol and sleep remains complex, several studies have shown that poor sleep quality and insomnia can be associated with altered cortisol patterns, either elevated evening levels or reduced morning responses [

37,

38]. These findings help interpret our own data, which showed improved PSQI scores alongside normalized cortisol levels, particularly in MB treatment groups. Additionally, evidence suggesting that higher morning cortisol levels may be associated with shorter sleep durations (less than five hours) supports the value of targeting cortisol modulation in interventions aimed at improving sleep and stress outcomes [

39]. Collectively, these prior findings enhance the interpretive strength of our results, suggesting that the MB’s beneficial effects on psychological well-being may be mediated, at least in part, through its regulatory influence on the HPA axis [

40].

4.4. Safety and Tolerability

MB supplementation for 25 days did not result in changes in oral temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, hematological measures or serum liver-based enzymes or creatinine. Adverse events were monitored systematically throughout the study using open-ended questioning and safety assessments, including vital signs and hematological measures. Two participants (one from GS-BAR and one from PLA-BAR) withdrew before study completion due to personal reasons and were excluded from the final Day 25 analysis. No serious adverse events attributable to the study product were observed. These observational measures, combined with no major reported adverse effects, are suggestive that short-term supplementation of the applied mushroom blend is well tolerated and generally safe.

4.5. Study Strengths

Strengths of the study include the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design, as this minimizes bias and increases internal validity. The inclusion of capsule and functional snack bar delivery formats provides practical insight into consumer-relevant supplementation strategies. Objective biomarkers (salivary cortisol) alongside validated psychological and sleep assessment tools (DASS-21 and PSQI) enhance the robustness of outcome measures. Furthermore, the safety assessments (vital signs and hematological analyses) support the short-term tolerability of the intervention.

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations to consider include the modest sample size (n=20 per group) and this was not a cross-over design, which limits statistical power. Although participants were randomized to treatment groups, baseline differences were observed across key outcome measures. Such variability is expected in modestly sized randomized trials and likely reflects natural sample variation rather than systematic imbalance. While within-group analyses were appropriately used to assess treatment-related changes, future research could benefit from incorporating baseline-adjusted statistical models such as ANCOVA or reporting percent change from baseline to enhance between-group comparisons and further strengthen the interpretability of treatment effects. There were improvements in the placebo groups over time, which seems to also indicate a placebo effect. This might have occurred due to placebo related factors (response bias, co-intervention bias, desire to change, emotional support, observation bias) and intervention effects (diet or lifestyle changes unrelated to study) [

41]. However, the magnitude of pre-post change in the treatment groups was significantly (p<0.05) greater than the changes observed in the PLA groups. The subjective nature of inclusion criteria and lack of dietary or lifestyle controls may introduce confounding factors. Additionally, the lack of objective, quantifiable sleep and mood measures, as well as the absence of long-term follow-up and limited geographic and demographic diversity may limit interpretation. Despite these limitations, the results provide preliminary evidence for the efficacy and safety of a mushroom-based supplement in supporting sleep quality and mood in young adults between 19-40 years of age.

5. Conclusions

Supplementation in either capsule or snack bar form of a commercially available, organic, mushroom blend consisting of organic Ganoderma lucidum, organic Cordyceps militaris fruiting body extract, organic Hericium erinaceus fruiting body extract, and organic fermented Cordyceps sinensis mycelium extract may positively influence mood state, sleep quality, and salivary cortisol levels. These mushrooms are rich in adaptogenic compounds such as β-glucans, triterpenes, and cordycepin, which support stress resilience, emotional well-being, and immune function. The observed benefits are consistent with existing research on Lion’s Mane for cognitive and mood support, Cordyceps for energy and metabolic regulation, and Reishi for calming and neuroendocrine balance. Moreover, the onset of potential benefits can occur within two weeks and continue to show improvements. The availability of both capsule and nutritional snack bar formats also provides greater flexibility for daily use. Lastly, general physical assessments combined with blood indices support the safety and tolerability of supplementation with this adaptogenic mushroom blend.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.R. and R.N.V.; methodology, R.N.V, M.K.R. and D.C.; software, R.W. and M.H.; validation, R.W., M.H., and R.N.V.; formal analysis, R.W., M.H., and D.C..; investigation; D.C.; resources, M.K.R and D.C.; data curation, D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.W.; writing—review and editing, M.K.R. and R.N.V.; supervision, R.N.V.; project administration, D.C.; funding, M.K.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored by NURA USA LLC, Irvine, CA. The sponsor provided the investigational ingredient and was involved in study design, manuscript development, and interpretation of results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of Shri B. M. Patil Medical College, Hospital & Research Centre, Vijayapura, Karnataka, India. The IEC functions as an independent body representing the institution, research participants, and the wider community, and is recognized by the Department of Health Research, Government of India. All research involving human participants at this institution is governed by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) National Ethical Guidelines, which align with international standards. The trial was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry – India (CTRI/2024/02/063100).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Clinical conduct and data collection were carried out independently by BioAgile Therapeutics, and statistical analysis was reviewed collaboratively with academic partners.

Disclosures: RNV, RW, and MH report consulting and/or advisory roles with NURA USA LLC. MKR is an employee of NURA USA LLC. All other authors declare no competing interests. Data and analyses are novel and unpublished. Participant data, data dictionary, and statistical code are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had a role in the design of the study; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to publish the results. The funders had no role in the collection, analyses, and interpretation of data.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MB |

Mushroom Blend |

| PLA |

Placebo |

| CAP |

Capsule |

| BAR |

Nutritional Snack Bar |

| HPA |

hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| DASS-21 |

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales |

| PSQI |

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| ANCOVA |

Analysis of Covariance |

| CRO |

Contract Research Organization |

References

- Saha, S.; Lim, C.C.W.; Cannon, D.L.; Burton, L.; Bremner, M.; Cosgrove, P.; Huo, Y.; McGrath, J. Co-morbidity between mood and anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety 2021, 38, 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellappa, S.L.; Aeschbach, D. Sleep and anxiety: From mechanisms to interventions. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2022, 61, 101583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.H.; Schaub, J.P.; Nagata, J.M.; Park, M.J.; Brindis, C.D.; Irwin, C.E. Jr. Young adult anxiety or depressive symptoms and mental health service utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health 2022, 70, 985–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, M.; Shimizu, K.; Kondo, R.; Hayashi, C.; Sato, D.; Kitagawa, K.; Ohnuki, K. Reduction of depression and anxiety by 4 weeks Hericium erinaceus intake. Biomedical Research 2010, 31, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levenson, J.; Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Colditz, J.B.; Primack, B.A. The association between social media use and sleep disturbance among young adults. Preventive Medicine 2016, 85, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.H. Cortisol in mood disorders. Stress 2004, 7, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, S.; Bell, L.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; Williams, C.M. A review of the effects of mushrooms on mood and neurocognitive health across the lifespan. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2024, 158, 105548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, D.; Maimes, S. (2007). Adaptogens: Herbs for strength, stamina, and stress relief. Inner Traditions/Bear & Co.

- Panossian, A. (2017). Understanding adaptogenic activity: Specificity of the pharmacological action of adaptogens and other phytochemicals. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Anusiya, G.; Gowthama Prabu, U.; Yamini, N.V.; Sivarajasekar, N.; Rambabu, K.; Bharath, G.; Banat, F. A review of the therapeutic and biological effects of edible and wild mushrooms. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 11239–11268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozarski, M.; Klaus, A.; Niksic, M.; Jakovljevic, D.; Helsper, J.P.F.G.; van Griensven, L.J.L.D. Antioxidative and immunomodulating activities of polysaccharide extracts of the medicinal mushrooms Agaricus bisporus, Agaricus brasiliensis, Ganoderma lucidum and Phellinus linteus. Food Chemistry 2015, 129, 1667–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazzi, F.; Adsuar, J.C.; Domínguez-Muñoz, F.J.; García-Gordillo, M.A.; Gusi, N.; Collado-Mateo, D. Ganoderma lucidum effects on mood and health-related quality of life in women with fibromyalgia. Healthcare (Basel) 2020, 8, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Wang, Y. Anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive and sedative-hypnotic activities of lucidone D extracted from Ganoderma lucidum. Cellular and Molecular Biology 2019, 65, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saljoughian, M. Adaptogenic or medicinal mushrooms. U.S. Pharmacist, /: HS–16–HS–18. https.

- Zhang, W.; Xu, L.; et al. Clinical studies of several well-known and valuable herbal medicines: A narrative review. Longhua Chinese Medicine, /: https, 8106. [Google Scholar]

- Wasser, S.P. Medicinal mushrooms as a source of antitumor and immunomodulating polysaccharides. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2002, 60, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shweta, Abdullah, S. ; Kumar, K.A. A brief review on the medicinal uses of Cordyceps militaris. Pharmacological Research – Modern Chinese Medicine 2023, 7, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, O.J.; Tang, J.; Tola, A.; Auberon, F.; Oluwaniyi, O.; Ouyang, Z. The genus Cordyceps: An extensive review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Fitoterapia 2018, 129, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maľučká, L.U.; Uhrinová, A.; Lysinová, P. Medicinal mushrooms Ophiocordyceps sinensis and Cordyceps militaris. Česká a slovenská farmacie 2022, 71, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuli, H.S.; Sandhu, S.S.; Sharma, A.K. Pharmacological and therapeutic potential of Cordyceps with special reference to Cordycepin. Biotechnology Advances 2014, 31, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.C.; Chen, Y.H.; et al. Functional study of Cordyceps sinensis and cordycepin in male reproduction: A review. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis 2017, 25, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.-H.; Tsai, C.-L.; Lien, Y.-Y.; Lee, M.-S.; Sheu, S.-C. High molecular weight of polysaccharides from Hericium erinaceus against amyloid beta-induced neurotoxicity. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2016, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spelman, K.; Sutherland, E.; Bagade, A. Neurological activity of Lion’s mane (Hericium erinaceus). Journal of Restorative Medicine 2017, 6, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, S.; Doughty, F.L.; Smith, E.F. The acute and chronic effects of Lion's mane mushroom supplementation on cognitive function, stress and mood in young adults: A double-blind, parallel groups, pilot study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. Adaptogens in mental and behavioral disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 2013, 36, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Inatomi, S. Improving effects of the mushroom Yamabushitake (Hericium erinaceus) on mild cognitive impairment: A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytotherapy Research 2009, 23, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kała, K.; Cicha-Jeleń, M.; Hnatyk, K.; Krakowska, A.; Sułkowska-Ziaja, K.; Szewczyk, A.; Lazur, J.; Muszyńska, B. Coffee with Cordyceps militaris and Hericium erinaceus fruiting bodies as a source of essential bioactive substances. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchimapura, S.; Thukham-Mee, W.; Tong-Un, T.; Sangartit, W.; Phuthong, S. Effects of a functional cone mushroom (Termitomyces fuliginosus) protein snack bar on cognitive function in middle age: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimopoulou, M.; Vareltzis, P.; Floros, S.; Androutsos, O.; Bargiota, A.; Gortzi, O. Development of a functional acceptable diabetic and plant-based snack bar using mushroom (Coprinus comatus) powder. Foods 2023, 12, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, J.D.; Crawford, J.R. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 2005, 44, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollayeva, T.; Thurairajah, P.; Burton, K.; Mollayeva, S.; Shapiro, C.M.; Colantonio, A. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index as a screening tool for sleep dysfunction in clinical and non-clinical samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2016, 25, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalač, P. A review of chemical composition and nutritional value of wild-growing and cultivated mushrooms. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2013, 93, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetvicka, V.; Gover, O.; Hayby, H.; Danay, O.; Ezov, N.; Hadar, Y.; Schwartz, B. Immunomodulating effects exerted by glucans extracted from the King Oyster culinary-medicinal mushroom Pleurotus eryngii (Agaricomycetes) grown in substrates containing various concentrations of olive mill waste. International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms 2019, 21, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachtel-Galor, S.; Yuen, J.; et al. (2011). Ganoderma lucidum, /: or Reishi): A medicinal mushroom. In Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects (2nd ed.). CRC Press/Taylor & Francis. https, 9275. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W.; Yang, C.; Fu, L.; He, X.; Wu, Y.; Pan, Y. Ganoderma lucidum improves sleep via increasing serotonergic and GABAergic systems in mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2022, 288, 114989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, E.D.; Fukushima, D.; Nogeire, C.; Roffwarg, H.; Gallagher, T.F.; Hellman, L. Twenty-four hour pattern of the episodic secretion of cortisol in normal subjects. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1971, 33, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, D.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Feige, B. The hyperarousal model of insomnia: A review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2010, 14, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, J.; Junghanns, K.; Hohagen, F. Sleep disturbances are correlated with decreased morning awakening salivary cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004, 29, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Aurea, C.; Poyares, D.; Piovezan, R.D.; Passos, G.; Tufik, S.; Mello, M.T. Objective short sleep duration is associated with the activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in insomnia. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria 2015, 73, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Kang, W.; Liu, H. Bioactive compounds from medicinal mushrooms and their potential effects on the HPA axis: A review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, K.R.; Williams, M.S.; Hoenemeyer, T.W.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; Dutton, G.R. Placebo effects in obesity research. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016, 24, 769–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).