Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Societal challenges are inherently complex and multi-tiered, arising from the interplay of diverse stakeholders with a spectrum of purposes and different perceptions and expectations, interdependent systems, and dynamic contextual factors that transcend single domains or disciplines. This paper presents a novel approach to developing a Reference Model of Governance tailored to a specific complex, multi-organisational enterprise facing socially complex challenges. Drawing on Angyal’s systems framework, the model introduces a three-dimensional structure with vertical, progression, and transverse dimensions, integrated within a holistic contextual whole. By mapping selected systems methodologies, including Soft Systems Methodology (SSM), Viable System Model (VSM), System Dynamics (SD), and Dependency Modelling, to these dimensions, the model offers a pragmatic, structured way to explore and regulate complex organisational behaviour. It enables collaborative inquiry, supports adaptive governance, and enhances the enterprise’s ability to address dynamic societal problems such as health, education, and public service delivery. The result is a governance reference model that captures both the operational and contextual realities of the enterprise, providing actionable insight for strategic design or diagnostic intervention. The novel approach is grounded in systemic and critical systems thinking and emphasises the use of methods for understanding to develop a common and shared understanding of the enterprise context and to surface multiple stakeholder perspectives.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Trajectory of Methodological Pluralism Developments

- The social context within which problematical situations exist is multidimensional [33]. Different paradigms focus on different aspects, each highlighting some and omitting others, indicating the benefit of using a variety of methodologies.

- Interventions are generally phased with stages on discovery, approach design, execution and review. Each stage will incorporate different tasks and perspectives, each benefitting from a different methodology or method [33].

- The lack of success of traditional methods and methodologies to resolve issues in practice leading to the consideration of new ways of thinking and entertaining the thought of multiple methodologies [110].

- Multiple methodologies enable a form of ‘triangulation’ that provided more confidence in findings if the same results were obtained from different methodologies [111].

2.2. Contemporary Theories of Social Systems

2.3. Conceptual Critique of Governance Models

2.4. Systemic Dimensions

- The vertical dimension: The vertical dimension represents the association between the goals of the organisation as defined by its controlling board or owner and its operations. It incorporates its culture and ways of working. Some of these are explicit, while others are implicit

- The dimension of progression: The dimension of progression represents the means-end processes of achievement. It is the series of observable actions that an organisation might undertake to achieve, or not, its goals. It may be taking place as observable behaviour but can equally be unobservable and represent strategic plans and intent. It is this dimension that really focuses on boundary critique and Midgley’s [122] process philosophy.

- The transverse dimension: The transverse dimension represents the breadth of multiple concurrent actions and the necessary coordination between them. Within the organisation, it could be the individuals in a team, the various departments that need to work together to achieve successful service delivery, or the coordination of service deliveries and business units for optimal resource utilisation, or work packages within a research programme.

- The Biosphere: The biosphere is the integration of the 3 perspectives placed within its environment and considered as a single reality. It is considered that there is no distinction between them, and they can only be separated by abstraction. This is the boundary critique proposed by Midgley. This abstraction incorporates both autonomous determination and environmental government “like two currents of opposing direction, inseparably united” [37, p. 101].

The Maladaptive Perspective

2.5. Mapping Methods to System’s Three Perspectives

3. Result

3.1. Candidate Methods

3.2. Philosophical Commitments

- Ontological commitment: Social reality is understood as dynamic and emergent, constituted by processes of interaction, interpretation, and systemic adaptation.

- Epistemological commitment: Knowledge arises through hermeneutic engagement, where understanding develops in a circular movement between the part and the whole, between pre-understanding and new interpretation.

- Axiological commitment: Inquiry is not value-neutral. Pragmatism, as emphasised in the extract, requires acknowledgment that values shape both the questions asked and the solutions sought. Governance research, therefore, must bring its value-laden character into the open.

| Orientation | Match to Requirements | Suitable Systems Method | Use of Method | Secondary contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Biosphere |

R1. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must enable boundary analysis. | Extended MPA 6 Questions / SSM (Checkland) |

Capture perspectives Develop consensus on purpose and key high-level activities (‘what’ should be done to achieve purpose) |

Use of Appreciative Inquiry in a World Café construct. |

| R3. Changes within the system (organisation) can be identified with regard to necessary activities as the organisation adapts to environmental changes. | SSM (Wilson) Dependency Modelling |

Re-model CPTM with revised Root Definitions. Enables identification of activities no longer relevant and additional activities to be include. Map the internal and external dependencies contributing to the organisation working well |

May result from periodic re-visit of Purpose (6 Questions, SSM (Checkland) PQR. Specific events captured by CLD Scenario Thinking/Planning exercise |

|

| R10. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent the non-linearity of relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | Logical dependencies between activities | ||

| VSM | Exploration of the environmental interactions and internal connections | Consideration of Angyal’s autonomy and heteronomy. | ||

| R11. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation can capture the feedbacks within the system, between the system and environment and within the environment. | System Dynamics |

Causal Loop Diagrams | Informed by E&T Causal Textures | |

| R12. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must enable one to capture / integrate the environmental inter-relationships as well as internal peer-peer inter-relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | Modelling ‘System Served’ and detailed analysis of logical dependencies. | ||

| VSM | Exploration of the environmental interactions and internal connections | Consideration of Angyal’s autonomy and heteronomy. Informed by E&T Causal Textures |

||

| R13. The organisation can be modelled in its wider context. | SSM (Wilson) | Modelling ‘System Served’ | ||

Vertical Dimension

|

R2. It must be possible to see the effects of history, corporate memory and drives to act. | Cognitive Maps | With respect to personal constructs (Kelly) seek to capture the organisational constructs | Kinston’s Hierarchy of purpose Explore stories |

| R4. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent ‘frames’, the perspective taken by the relevant management team according to differing levels of abstraction. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation is likely to be recursive (nested) with increasing granularity both horizontally and vertically. | Extended MPA 6 Questions / SSM (Checkland) |

Capture perspectives Develop consensus on purpose and key high-level activities (‘what’ should be done to achieve purpose) |

Small group conversations | |

| Cognitive Maps | With respect to personal constructs (Kelly) seek to capture the organisational constructs | Kinston’s Hierarchy of purpose | ||

| R11. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation can capture the feedbacks within the system, between the system and environment and within the environment. | SD |

Causal Loop Diagrams | informed by E&T Causal Textures | |

Progression Dimension

|

R3. Changes within the system (organisation) can be identified with regard to necessary activities as the organisation adapts to environmental changes. | SSM (Wilson) Dependency Modelling |

Re-model CPTM with revised Root Definitions. Enables identification of activities no longer relevant and additional activities to be include. Map the internal and external dependencies contributing to the organisation working well |

May result from periodic re-visit of Purpose (6 Questions, SSM (Checkland) PQR. Specific events captured by CLD Scenario Thinking/Planning exercise |

| R5. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to determine holistically activities relevant to the agreed frames but maintain logical dependencies and capture the richness of interaction. | SSM (Wilson) | Consensus Primary Task Model, either Enterprise Model or ‘W’ Decomposition | MPA, 6 Questions, Cognitive Maps Dependency models? |

|

| R7. It should be possible to determine clusters of elements collaborating at short range as well as indicate the longer-range inter-relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | RACI analysis | Mapping to VSM | |

| VSM | Initial construction of relevant VSMs | Informed by SSM analysis | ||

| R8. Dependencies between elements must be captured. | SSM (Wilson) | RACI analysis | Mapping to VSM | |

| VSM Dependency Models? |

Initial construction of relevant VSMs | Informed by SSM analysis | ||

| R9. Measures of performance can be identified. | SSM (Wilson) | Activity Analysis | Also consideration of metrics SD modelling might inform up-stream and down-stream points of measurement and optimisation |

|

| R10. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent the non-linearity of relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | Logical dependencies between activities | ||

| VSM | Exploration of the environmental interactions and internal connections | Consideration of Angyal’s autonomy and heteronomy. | ||

| R11. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation can capture the feedbacks within the system, between the system and environment and within the environment. | SD |

Causal Loop Diagrams | informed by E&T Causal Textures | |

Transverse Dimension

|

R3. Changes within the system (organisation) can be identified with regard to necessary activities as the organisation adapts to environmental changes. | SSM (Wilson) Dependency Modelling |

Re-model CPTM with revised Root Definitions. Enables identification of activities no longer relevant and additional activities to be include. Map the internal and external dependencies contributing to the organisation working well |

May result from periodic re-visit of Purpose (6 Questions, SSM (Checkland) PQR. Specific events captured by CLD Scenario Thinking/Planning exercise |

| R4. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent ‘frames’, the perspective taken by the relevant management team according to differing levels of abstraction. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation is likely to be recursive (nested) with increasing granularity both horizontally and vertically. | Extended MPA 6 Questions / SSM (Checkland) |

Capture perspectives Develop consensus on purpose and key high-level activities (‘what’ should be done to achieve purpose) |

Small group conversations | |

| Cognitive Maps | With respect to personal constructs (Kelly) seek to capture the organisational constructs | Kinston’s Hierarchy of purpose | ||

| R6. Sub-organisations within the organisation or enterprise can be identified that have their own discrete properties (purpose). | SSM (Wilson) | Consensus Primary Task Model, either Enterprise Model or ‘W’ Decomposition | MPA, 6 Questions, Cognitive Maps Mapping to VSM |

|

| VSM | Discrete VSMs within the VSM ‘set’ | Informing and informed by SSM | ||

| R7. It should be possible to determine clusters of elements collaborating at short range as well as indicate the longer-range inter-relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | RACI analysis | Mapping to VSM | |

| VSM | Initial construction of relevant VSMs | Informed by SSM analysis | ||

| R8. Dependencies between elements must be captured. | SSM (Wilson) | RACI analysis | Mapping to VSM | |

| VSM Dependency Model? |

Initial construction of relevant VSMs | Informed by SSM analysis | ||

| R10. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent the non-linearity of relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | Logical dependencies between activities | ||

| VSM | Exploration of the environmental interactions and internal connections | Consideration of Angyal’s autonomy and heteronomy. | ||

| R11. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation can capture the feedbacks within the system, between the system and environment and within the environment. | SD |

Causal Loop Diagrams | Informed by E&T Causal Textures | |

| R12. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must enable one to capture / integrate the environmental inter-relationships as well as internal peer-peer inter-relationships. | SSM (Wilson) | Modelling ‘System Served’ and detailed analysis of logical dependencies. | ||

| VSM | Exploration of the environmental interactions and internal connections | Consideration of Angyal’s autonomy and heteronomy. Informed by E&T Causal Textures |

4. Discussion

4.1. Methods for Understanding

4.2. The Main Systems Methods

Soft Systems Methodology

Viable System Model

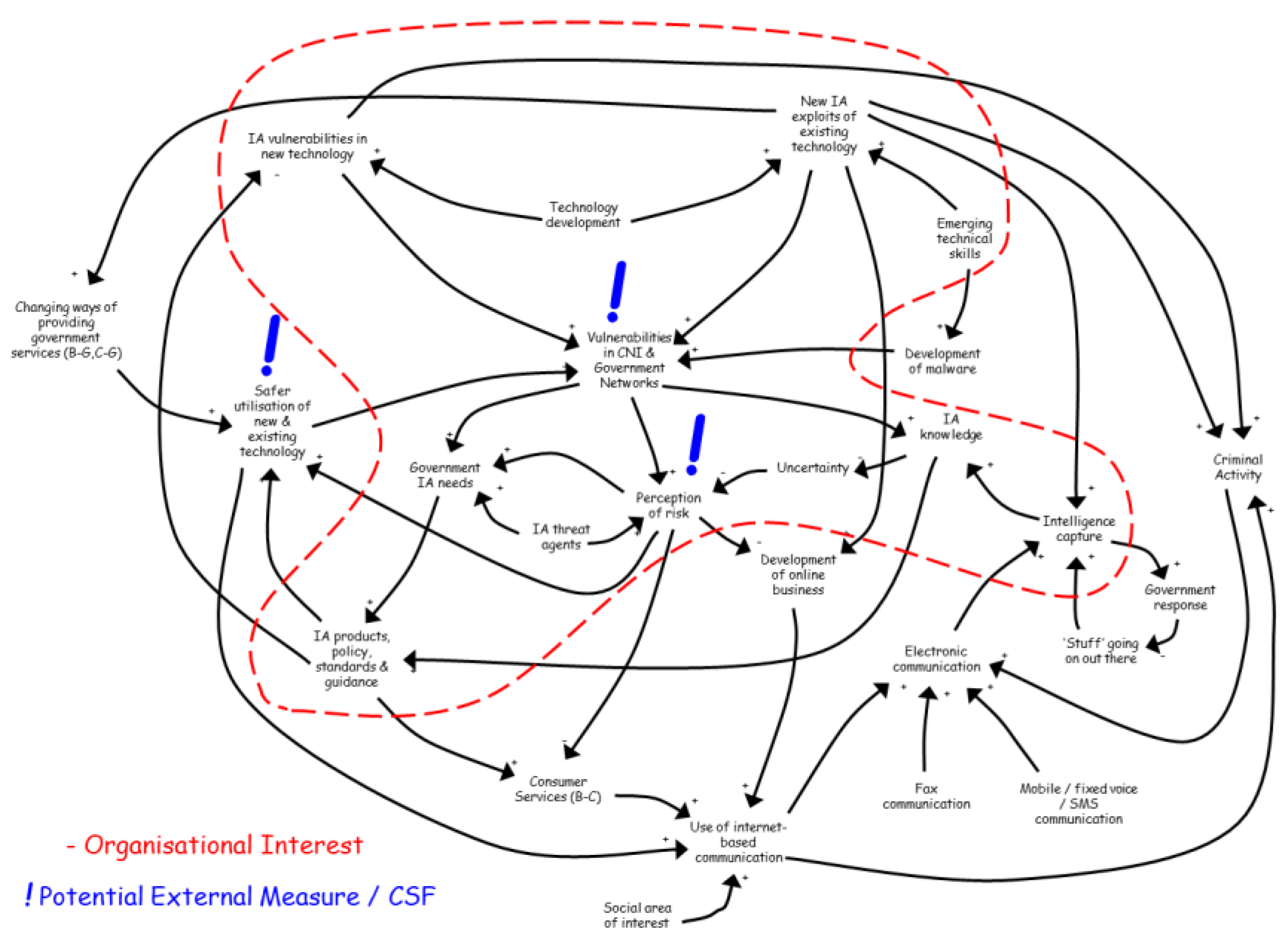

System Dynamics, Including Causal Loop Modelling

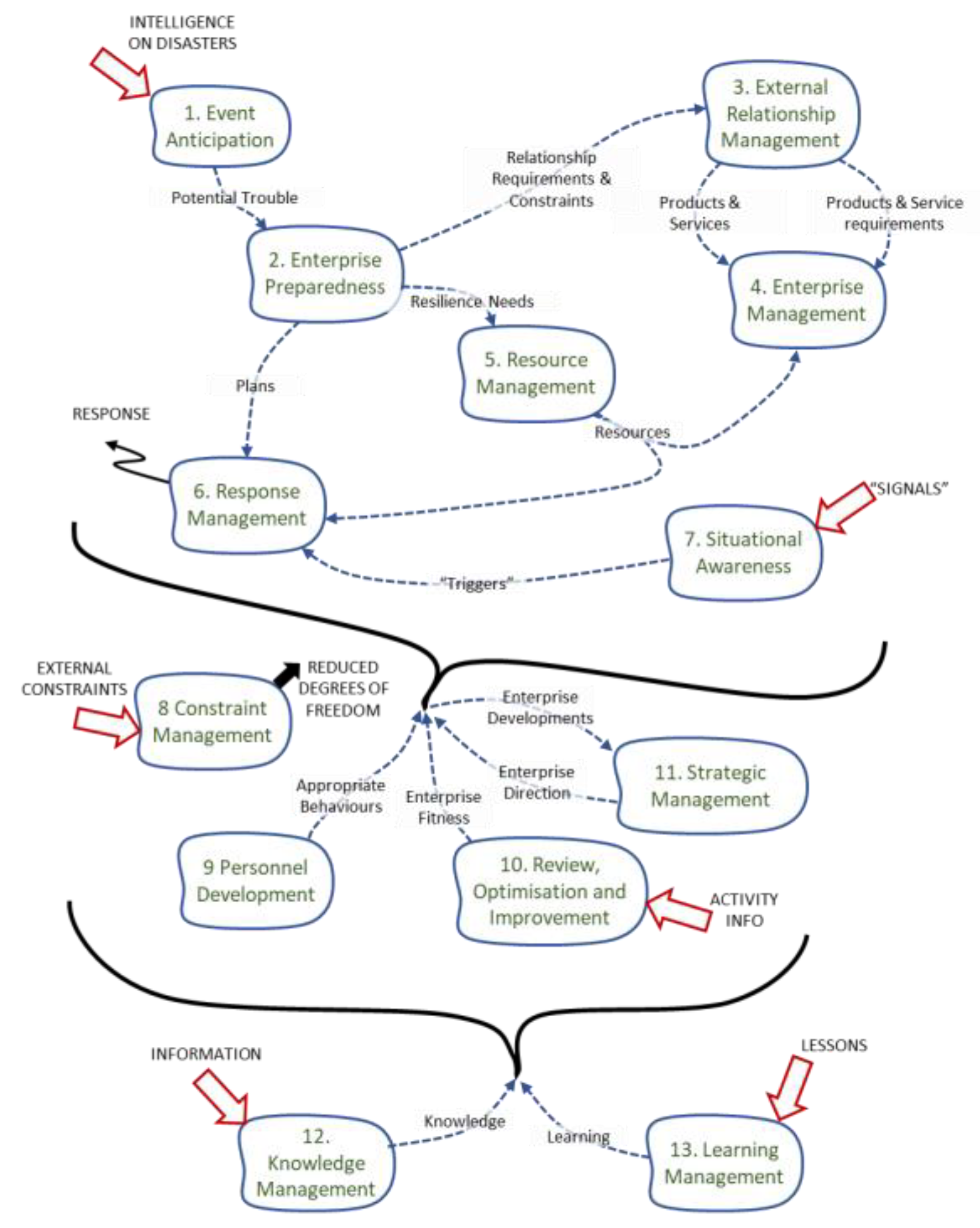

Dependency Modelling

4.3. Shaping with Respect to the Causal Texture of Organisational Environments

4.4. Augmenting Thinking with Generic SSM Models

4.5. Utility of Methods

5. Assumptions and Limitations of the Reference Model

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

- Appendix A – Core Terms

- Appendix B - Comparison of Systems Methods

- Appendix C - Example of an SSM Activity table and Description of SSM activity analysis table headings

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLD | Causal Loop Diagram |

| CPTM | Consensus Primary Task Model |

| MPA | Multi-Perspective Approach |

| SD | System Dynamics |

| SSM | Soft Systems Methodology |

| VSM | Viable System Modelling |

References

- G. George, J. Howard-Grenville, A. Joshi, and L. Tihanyi, “Understanding and tackling societal grand challenges through management research,” Academy of management journal, vol. 59, no. 6, pp. 1880–1895, 2016.

- J. Mingers, Self-producing systems: implications and applications of autopoiesis. London & New York: Plenum Press, 1995.

- M. C. Jackson, Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2019.

- W. James, Pragmatism: a new name for some old ways of thinking. New York: Longmans, 1907.

- P. Vivo, D. M. Katz, and J. B. Ruhl, “A complexity science approach to law and governance,” 2024, The Royal Society.

- C. B. Keating, P. F. Katina, and J. M. Bradley, “Complex system governance: Concept, challenges, and emerging research,” International Journal of System of Systems Engineering, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 263–288, 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Rabelo, S. N. Costa, and D. Romero, “A Governance Reference Model for Virtual Enterprises,” in 15th Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises (PROVE), Nether-lands, 2014, pp. 60–70. [CrossRef]

- C. B. Keating, P. F. Katina, C. W. Chesterman, and J. C. Pyne, Eds., Complex System Governance: Theory and Practice, 1st ed. Springer, Cham, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. van der Heijden, “The Value of Systems Thinking for and in Regulatory Governance: An Evidence Synthesis,” Sage Open, vol. 12, no. 2, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Espejo, “Cybernetics of Governance: The Cybersyn Project 1971–1973,” no. September, pp. 71–90, 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. Lewis and G. Millar, “The viable governance model - A theoretical model for the governance of IT,” Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, HICSS, pp. 1–10, 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. Baijens, T. Huygh, and R. Helms, “Establishing and theorising data analytics governance: a descriptive framework and a VSM-based view,” Journal of Business Analytics, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 101–122, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Espejo, “Cybersyn, big data, variety engineering and governance,” AI Soc, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 1163–1177, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, “Governance for sustainability: learning from VSM practice,” Kybernetes, vol. 44, no. 6–7, pp. 955–969, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Schwaninger, “Governance for intelligent organizations: a cybernetic contribution,” Kybernetes, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 35–57, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Davies, “Models of Governance - A Viable Systems Perspective,” Australasian Journal of Information Systems, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 57–66, 2002. [CrossRef]

- T. Huygh and S. De Haes, “Investigating IT Governance through the Viable System Model,” Information Systems Management, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 168–192, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Conant and W. Ross Ashby, “Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system,” Int J Syst Sci, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 89–97, 1970. [CrossRef]

- N. Ulibarri, K. Emerson, M. T. Imperial, N. W. Jager, J. Newig, and E. Weber, “How does collaborative governance evolve? Insights from a medium-n case comparison,” Policy Soc, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 617–637, 2020.

- P. Cilliers, Complexity and Postmodernism. Understanding complex systems. London & New York: Routledge, 1998.

- G. Sommerhoff, Analytical Biology. London: Oxford University Press, 1950.

- W. R. Ashby, An Introduction to Cybernetics, Internet. London: Chapman and Hall, 1956.

- R. C. Conant and W. Ross Ashby, “Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system,” Int J Syst Sci, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 89–97, 1970. [CrossRef]

- F. Emery and E. Trist, “The Causal Texture of Organizational environments,” Human Relations, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 21–31, 1965.

- E. Trist, “The environment and system-response capability,” Futures, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 113–127, 1980. [CrossRef]

- Angyal, Foundations for a science of personality, 4th printi. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1941.

- E. Trist, “Andras Angyal and Systems Thinking,” in Planning for Human Systems, J.-M. Choukroun and R. Snow, Eds., Philadelphia: Busch Centre, The Wharton School of the Uniersity of Pannsylvania, 1992, ch. 9, pp. 111–132.

- F. E. Emery, “Adaptation to Turbulent Environments,” in Towards a Social Ecology, F. E. Emery and E. L. Trist, Eds., London: Plenum Publishing Company Ltd, 1973, ch. 5, pp. 57–67.

- M. C. Jackson, “Critical systems practice 2: Produce—Constructing a multimethodological intervention strategy,” Syst Res Behav Sci, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 594–609, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Midgley, J. D. Nicholson, and R. Brennan, “Dealing with challenges to methodological pluralism: The paradigm problem, psychological resistance and cultural barriers,” Industrial Marketing Management, vol. 62, pp. 150–159, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Mingers, “Variety is the spice of life: Combining soft and hard OR/MS methods,” International Transactions in Operational Research, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 673–691, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Munro and J. Mingers, “The use of multimethodology in practice—results of a survey of practitioners,” Journal of the Operational Research Society, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 369–378, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Mingers and J. Brocklesby, “Multimethodology: Towards a framework for mixing methodologies,” Omega (Westport), vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 489–509, 1997. [CrossRef]

- Hilton, “A methodology for modelling organisational governance: building the ‘Good Regulator’ model for organisations through the application of multiple systems methods.,” Cranfield University, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://dspace.lib.cranfield.ac.uk/handle/1826/23723.

- N. Babüroǵlu, “Tracking the development of the Emery-Trist systems paradigm (ETSP),” Systems Practice, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 263–290, 1992. [CrossRef]

- E. Trist, “Andras Angyal and Systems Thinking,” in Planning for Human Systems, J.-M. Choukroun and R. Snow, Eds., Philadelphia: Busch Centre, The Wharton School of the University of Pannsylvania, 1992, ch. 9, pp. 111–132.

- Angyal, Foundations for a science of personality, 4th printi. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1941.

- G. A. Kelly, The Psychology of Personal Constructs: Volume One A Theory of Personality. New York, NY, US: W W Norton & Co, 1955.

- P. Checkland, Systems Thinking, Systems Practice: Includes a 30-year Retrospective. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1999.

- C. W. Churchman, The Systems Approach and its Enemies. New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1979.

- G. Morgan, Imaginization: The Art of Creative Management. Sage Publications, 1993.

- W. Ulrich and M. Reynolds, “Critical Systems Heuristics,” in Systems Approaches to Managing Change: A Practical Guide, M. Reynolds and S. S. Holwell, Eds., 2010, pp. 243–292. [CrossRef]

- C. Eden, “Analyzing cognitive maps to help structure issues or problems,” Eur J Oper Res, vol. 159, no. 3, pp. 673–686, 2004. [CrossRef]

- N. Luhmann, Social Systems. Stanford, CA: Stanfory University Press, 1995.

- J. Mingers, “Can social systems be autopoietic? Assessing Luhmann’s social theory,” Sociological Review, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 278–299, 2002. [CrossRef]

- E. Jaques, “The Development of Intellectual Capability: A Discussion of Stratified Systems Theory,” J Appl Behav Sci, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 361–383, 1986. [CrossRef]

- W. Kinston, “Purpose & Translation Of Values into Action,” Systems Research, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 147–160, 1986.

- E. Jaques, Requisite Organization: A Total System for Effective Managerial Organization and Managerial Leadership for the 21st Century, Revised 2n. Oxford: Routledge, 2006.

- G. Stamp, “Levels and Types of Managerial Capability,” Journal of Management Studies, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 277–298, 1981. [CrossRef]

- G. Stamp, “The individual, the organisation and the path to mutual appreciation,” First published in Personnel Management, amended BIOSS 2004.

- G. Midgley, Systemic Intervention: Philosophy, methodology, and practice. in Contemporary Systems Thinking. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2000. [CrossRef]

- C. Jackson, “Critical systems practice 1 : Explore - starting a multi- methodological intervention,” Syst Res Behav Sci, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 839–858, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Jackson, “Critical systems practice 2: Produce—Constructing a multimethodological intervention strategy,” Syst Res Behav Sci, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 594–609, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Angyal, “A Logic of Systems,” in Systems Thinking, Vol One (Ch1), Revised Ed., F. E. Emery, Ed., Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd, 1981, ch. 1.

- D. C. Phillips, “The Methodological Basis of Systems Theory,” Academy of Management Journal, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 469–477, 1972. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Conant, “The Information Transfer Required in Regulatory Processes,” IEEE Transactions on Systems Science and Cybernetics, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 334–338, 1969. [CrossRef]

- L. von Bertalanffy, “General Systems Theory,” General Systems, vol. 1, pp. 1–10, 1956.

- K. E. Boulding, “General Systems Theory—the Skeleton of Science,” Manage Sci, vol. 2, pp. 197–208, 1956.

- W. R. Ashby, An Introduction to Cybernetics, Internet. London: Chapman and Hall, 1956.

- W. R. Ashby, Design for a Brain. London: Chapman and Hall, 1960.

- Rosenblueth, N. Wiener, and J. Bigelow, “Behavior, Purpose and Teleology,” Philos Sci, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 18, 1943. [CrossRef]

- Wiener, Cybernetics, 2nd Edn. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1961.

- H. A. Simon, “The architecture of complexity,” Proc Am Philos Soc, vol. 106, no. 6, pp. 467–482, 1962.

- R. G. Coyle, System Dynamics Modelling: A practical approach. Springer-Science + Business Media, B.V., 1996. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Forrester, Industrial Dynamics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1961.

- J. W. Forrester, “The beginning of System Dynamics [paper],” in Banquet Talk at the International Meeting of the System Dynamics Society., Stuttgart, Germany, 1989, pp. 1–16.

- G. Al Jenkins, “The systems approach,” in Systems behaviour, J. Beishon and G. Peters, Eds., New York: Harper and Row, 1969, ch. 4, p. 56.

- S. Beer, Brain of the firm. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1981.

- S. Beer, The heart of enterprise. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1994.

- Checkland, “Information systems and systems thinking: Time to unite?,” Int J Inf Manage, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 239–248, 1988. [CrossRef]

- Checkland, Systems Thinking, Systems Practice: Includes a 30-year Retrospective. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1999.

- M. C. Jackson, “Nature of ‘Soft’ Systems Thinking: the Work of Churchman, Ackoff and Checkland.,” Journal of applied systems analysis, vol. 9, no. April 1982, pp. 17–39, 1982.

- C. W. Churchman, The Systems Approach. New York: Delta/Dell Publishing, 1968.

- C. W. Churchman, “Perspectives of the Systems Approach,” Interfaces (Providence), vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 6–11, 1974. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Churchman and F. Emery, “On Various Approaches to the Study of Organizations,” in First International Conference of Operational Research and the Social Sciences, Cambridge, 1964, pp. 1–16.

- Checkland and J. Scholes, Soft Systems Methodology in Action. John Wiley & Sons, 1990.

- D. Cooperrider, D. Whitney, and J. M. Stavros, Appreciative Inquiry Handbook for Leaders of Change, 2nd Edn. Brunswick: Crown Custom Publishing, Inc, 2008.

- J. Varey, “Appreciative systems ∗,” pp. 1–6, 1998.

- G. Vickers, Freedom in a Rocking Boat: Changing Values in an Unstable Society. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd, 1972.

- William. Isaacs, Dialogue and the art of thinking together : a pioneering approach to communicating in business and in life. New York: Currency, 1999.

- L. Ackoff, “Resurrecting the Future of Operational Research,” J Oper Res Soc, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 189–199, 1979.

- P. M. Senge and J. D. Sterman, “Systems thinking and organizational learning: Acting locally and thinking globally in the organization of the future,” Eur J Oper Res, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 137–150, 1992. [CrossRef]

- W. Ulrich, “Beyond methodology choice: Critical systems thinking as critically systemic discourse,” Journal of the Operational Research Society, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 325–342, 2003. [CrossRef]

- J. Brocklesby, “Let the jury decide: Assessing the cultural feasibility of total systems intervention,” Systems Practice, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 75–86, 1994. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Flood and M. C. Jackson, Creative Problem Solving: Total Systems Intervention. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1991.

- Frandberg, “Systems Thinking - A Studie of Alternatives of R. Flood, M. Jackson, W. Ulrich, G. Midgley,” International Journal of Computers, Systems and Signals, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 33–41, 2003.

- W. J. Gregory, “Critical systems thinking and pluralism : a new constellation,” 1992.

- W. J. Gregory, “Discordant pluralism: A new strategy for critical systems thinking,” Systems Practice, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 605–625, 1996. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Jackson, Systems approaches to management. New York: Kluwer Academic - Plenum, 2000.

- M. C. Jackson, “The power of multi-methodology: Some thoughts for John Mingers,” Journal of the Operational Research Society, vol. 54, no. 12, pp. 1300–1301, 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Jackson and P. Keys, “Towards a system of systems methodologies,” Journal of the Operational Research Society, vol. 35, no. 6, pp. 473–486, 1984. [CrossRef]

- G. Midgley, “The sacred and profane in critical systems thinking,” Systems Practice, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 5–16, 1992. [CrossRef]

- G. Midgley, “Pluralism and the legitimation of system science,” Systems practice, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 147–172, 1992.

- G. Midgley, “Science as Systemic Intervention: Some Implications of Systems Thinking and Complexity for the Philosophy of Science,” Syst Pract Action Res, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 77–97, 2003. [CrossRef]

- J. Mingers, “Paradigm wars: Ceasefire announced who will set up the new administration?,” Journal of Information Technology, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 165–171, 2004. [CrossRef]

- J. Mingers, “Classifying philosophical assumptions: A reply to ormerod,” Journal of the Operational Research Society, vol. 56, no. 4, pp. 465–467, 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. Mingers and A. Gill, Eds., Multimethodology: The theory and practice of combining management science methodologies. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1997.

- J. C. Oliga, “Methodological foundations of systems methodologies,” Systems Practice, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 87–112, 1988. [CrossRef]

- J. Mingers, “Real-izing information systems: Critical realism as an underpinning philosophy for information systems,” Information and Organization, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 87–103, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Egan et al., “Guidance on Systems Approaches to Local Public Health Evaluation Part 1 : Introducing systems thinking,” no. March, pp. 1–19, 2019, [Online]. Available: https://sphr.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/NIHR-SPHR-SYSTEM-GUIDANCE-PART-1-FINAL_SBnavy.pdf.

- M. Egan et al., “Guidance on Systems Approaches to Local Public Health Evaluation Part 2 : What to consider when planning a systems evaluation,” no. March, pp. 1–20, 2019.

- D. Wight, E. Wimbush, R. Jepson, and L. Doi, “Six steps in quality intervention development (6SQuID),” J Epidemiol Community Health (1978), vol. 70, no. 5, pp. 520–525, 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. Edwards, J. O’Mahoney, and S. Vincent, Studying Organizations using Critical Realism: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- J. Longhofer and J. Floersch, “The Coming Crisis in Social Work: Some Thoughts on Social Work and Science,” Res Soc Work Pract, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 499–519, 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Pawson, “Evidence-based Policy: The Promise of ‘Realist Synthesis,’” Evaluation, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 340–358, 2002.

- S. Porter, “Realist evaluation: An immanent critique,” Nursing Philosophy, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 239–251, 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. Shannon-Baker, “Making Paradigms Meaningful in Mixed Methods Research,” J Mix Methods Res, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 319–334, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Jackson, “Present positions and future prospects in management science,” Omega (Westport), vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 455–466, 1987. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Ormerod, “The design of organisational intervention: Choosing the approach,” Omega-International Journal of Management Science, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 415–435, 1997. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Jackson, “Pluralism in systems thinking and practice,” in Multimethodology, J. Mingers and A. Gill, Eds., Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1997, ch. 13, pp. 347–378.

- J. Mingers, Systems thinking, critical realism and philosophy: A confluence of ideas. Taylor and Francis, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, The social system. New York: Free Press, 1951.

- Giddens, The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Polity Press, 1984.

- J. Habermas, The theory of communicative action volume 2: The critique of functional reason, McCarthy, T. (transl.). London: Heinemann, 1987.

- C. Wright, “Multiple Systems Thinking Methods for Resilience Research,” Cardiff University, 2012.

- E. Trist, “Andras Angyal and Systems Thinking,” in Planning for Human Systems, J.-M. Choukroun and R. Snow, Eds., Philadelphia: Busch Centre, The Wharton School of the Uniersity of Pannsylvania, 1992, ch. 9, pp. 111–132.

- G. Hughes, “A systems approach to student’s motivation and academic achievement,” University of Aston in Birmingham, 1975.

- D. C. Phillips, “The Methodological Basis of Systems Theory,” Academy of Management Journal, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 469–477, 1972. [CrossRef]

- N. Baburoglu, “The Vortical Environment: The Fifth in the Emery-Trist Levels of Organizational Environments,” Human Relations, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 181–210, 1988. [CrossRef]

- F. E. Emery, “Adaptation to Turbulent Environments,” in Towards a Social Ecology, F. E. Emery and E. L. Trist, Eds., London: Plenum Publishing Company Ltd, 1973, ch. 5, pp. 57–67.

- E. Trist, “The environment and system-response capability: A futures perspective,” Futures, vol. 12, pp. 113–127, 1979. [CrossRef]

- G. Midgley, Systemic Intervention: Philosophy, methodology, and practice. in Contemporary Systems Thinking. Boston, MA: Springer US, 2000. [CrossRef]

- F. E. Emery, “Active Adaptation,” in Futures we are in, Martinus Nijhoff, Ed., Leiden, 1977, pp. 67-131`.

- Angyal, Neurosis and treatment: a holistic theory. New York: The Viking Press, 1965.

- G. Sommerhoff, Analytical Biology. London: Oxford University Press, 1950.

- B. Wilson, Systems: Concepts, Methodologies, and Applications. John Wiley & Sons, 1990.

- D. F. Andersen, J. A. M. Vennix, G. P. Richardson, and E. A. J. A. Rouwette, “Group model building: Problem structuring, policy simulation and decision support,” Journal of the Operational Research Society, vol. 58, no. 5, pp. 691–694, 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. Meadows, Thinking in Systems: A primer. London: Earthscan, 2008.

- S. Beer, Diagnosing the system for organizations. John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 1985.

- D. Slater, “A Dependency Modelling Manual,” 2016.

- The Open Group, “Dependency Modeling (O-DM): Constructing a Data Model to Manage Risk and Build Trust between Inter-Dependent Enterprises,” pp. 1–50, 2012, [Online]. Available: https://publications.opengroup.org/downloadable/download/link/id/MC45MTQ2MTgwMCAxNTE1NjgxOTMwNjgyMTI3NDc1NDU3Ng,,/.

- B. Wilson and K. Van Haperen, Soft systems thinking, methodology and the management of change. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- G. Morgan, Imaginization: The Art of Creative Management. Sage Publications, 1993.

- C. Eden, “Cognitive mapping,” Eur J Oper Res, vol. 36, pp. 1–13, 1988.

- C. Eden, “Analyzing cognitive maps to help structure issues or problems,” Eur J Oper Res, vol. 159, no. 3, pp. 673–686, 2004. [CrossRef]

- J. Hilton, “A Summary Report on the Systems Approach to the development of The GroundsWell Consortium,” pp. 1–18, 2020, [Online]. Available: www.cranfield.ac.uk.

- J. Brown, D. Isaacs, and T. W. C. Community, The World Café: Shaping our futures through conversations that matter. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc, 2005.

- D. Cooperrider, D. Whitney, and J. M. Stavros, Appreciative Inquiry Handbook for Leaders of Change, 2nd Edn. Brunswick: Crown Custom Publishing, Inc, 2008.

- G. Cairns and G. Wright, Scenario Thinking: Preparing your organization for the future in an unpredictable world., 2nd Edn. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

- J. Hilton, “Using systems techniques to define information requirements,” The Open Group, Barcelona, 1996.

- F. E. Emery and E. L. Trist, “The causal texture of organizational environments,” Human relations, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 21–32, 1965.

- R. Ashby, Design for a Brain. London: Chapman and Hall, 1960.

- J. Hilton, T. Riley, and C. Wright, “Using multiple perspectives to design resilient systems for agile enterprises,” SysCon 2013 - 7th Annual IEEE International Systems Conference, Proceedings, pp. 437–441, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Hilton, C. Wright, and V. Kiparoglou, “Building resilience into systems,” SysCon 2012 - 2012 IEEE International Systems Conference, Proceedings, pp. 638–645, 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. Wright, V. Kiparoglou, M. Williams, and J. Hilton, “A framework for resilience thinking,” Procedia Comput Sci, vol. 8, pp. 45–52, 2012. [CrossRef]

- N. Luhmann, Introduction to Systems Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013.

- G. Ramírez-Gutiérrez, P. P. Cardoso Castro, and R. Tejeida-Padilla, “A Methodological Proposal for the Complementarity of the SSM and the VSM for the Analysis of Viability in Organizations,” Syst Pract Action Res, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 331–357, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Zolfagharian, A. G. L. Romme, and B. Walrave, “Why, when, and how to combine system dynamics with other methods: Towards an evidence-based framework,” Journal of Simulation, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 98–114, 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Checkland, “Soft Systems Methodology: A Thirty Year Retrospective,” Systems Research and Behavioral ScienceSyst. Res, vol. 17, pp. S11–S58, 2000.

- P. Checkland and J. Poulter, Learning for Action: A Short Definitive Account of Soft Systems Methodology and Its Use for Practitioners, Teachers and Students. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2006.

- B. Wilson, Soft Systems Methodology: Conceptual model building and its contribution. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2001.

- R. Espejo and A. Reyes, Organizational Systems: Managing complexity with the Viable Systems Model. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Perez Rios, Design and Diagnosis for Sustainable Organizations. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2012.

- S. Galea, M. Riddle, and G. A. Kaplan, “Causal thinking and complex system approaches in epidemiology,” Int J Epidemiol, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 97–106, 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. Vandenbroeck, J. Goossens, and M. Clemens, “Tackling Obesities: Future Choices – Building the Obesity System Map,” Foresight, p. 80, 2007, [Online]. Available: www.foresight.gov.uk.

- D. Meadows, “Leverage Points Places to Intervene in a System,” Hartland VT, USA, 1999. Accessed: Jun. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://www.donellameadows.org/wp-content/userfiles/Leverage_Points.pdf.

- D. P. Stroh, Systems Thinking for Social Change. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2015.

- D. Besselink et al., “Uncovering the Dynamic System Driving Older Adults’ Vitality: A Causal Loop Diagram Co-Created With Dutch Older Adults,” Health Expectations, vol. 28, no. 4, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. A. M. Vennix, Group Model Building: Facilitating team learning using system dynamics. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1996.

- J. D. Sterman, Business Dynamics: Systems thinking and modeling for a complex world. McGraw Hill, 2000.

- K. E. Maani and R. Y. Cavana, Systems Thinking and Modelling: Understanding Change and Complexity. Pearson Education, 2000.

| No | Requirement Statement |

|---|---|

| R1 | The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must enable boundary analysis. |

| R2 | It must be possible to see the effects of history, corporate memory and drives to act |

| R3 | Changes within the system (organisation) can be identified regarding necessary activities as the organisation adapts to environmental changes. |

| R4 | The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent ‘frames’, the perspective taken by the relevant management team according to differing levels of abstraction. The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation is likely to be recursive (nested) with increasing granularity both horizontally and vertically. |

| R5 | The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to determine holistically activities relevant to the agreed frames but maintain logical dependencies and capture the richness of interaction. |

| R6 | Sub-organisations within the organisation or enterprise can be identified that have their own discrete properties (purpose). |

| R7 | It should be possible to determine clusters of elements that collaborate at short range, as well as to indicate the longer-range interrelationships. |

| R8 | Dependencies between elements must be captured. |

| R9 | Measures of performance can be identified. |

| R10 | The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must be able to represent the non-linearity of relationships. |

| R11 | The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation can capture the feedback within the system, between the system and the environment and within the environment. |

| R12 | The Reference Model of Governance for a Specific Organisation must enable one to capture / integrate the environmental inter-relationships as well as internal peer-peer inter-relationships. |

| R13 | The organisation can be modelled in its wider context. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).