Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- ‘Healthy’ or ‘good’ governance

- Great Barrier Reef (GBR) context

- Complexities and challenges of GBR governance

2. Methodological Approach

2.1. Developing the Framework

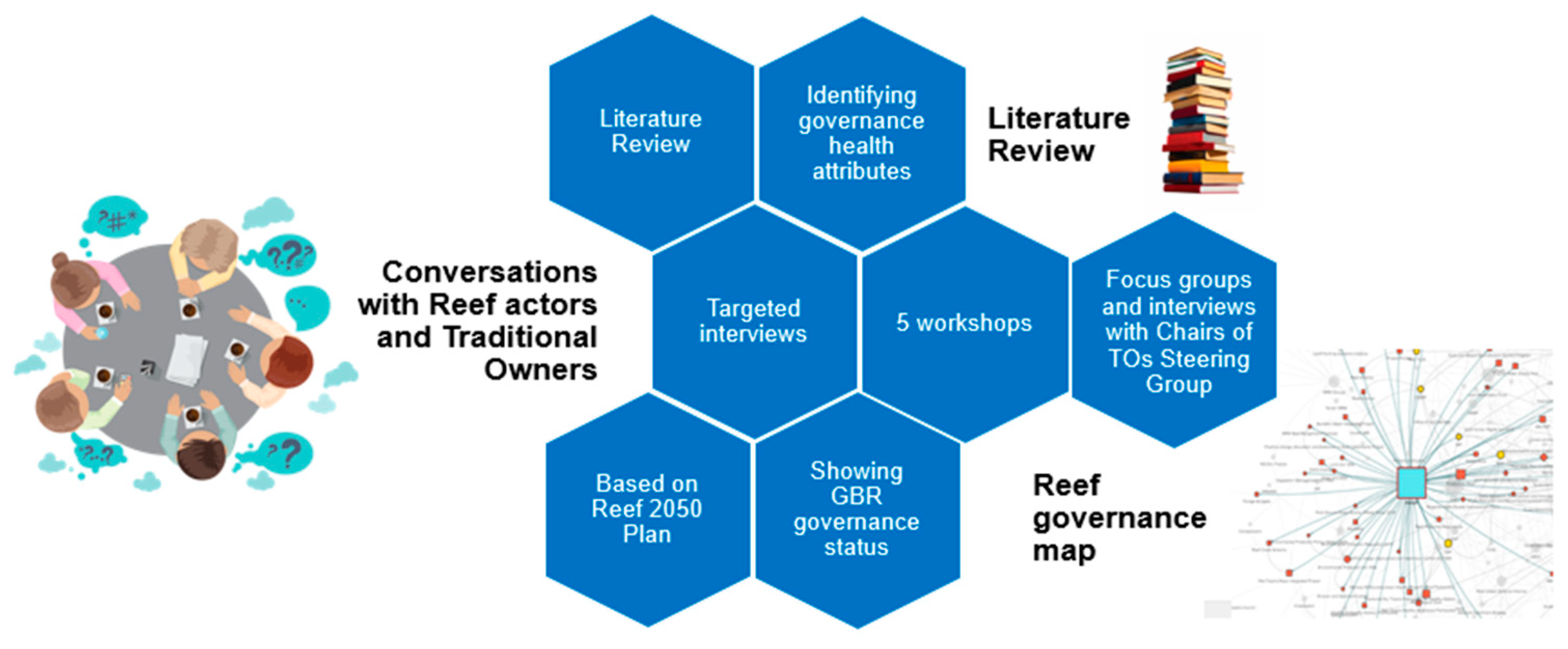

2.1.1. Literature Review

- globally, there is interest and attention at a range of scales (international to local) in measuring the extent to which complex governance systems are ‘good’ or ‘healthy’; and

- a strong governance monitoring system is needed to support the review, implementation, and delivery of the Reef 2050 Plan to improve outcomes in the GBR.

2.1.2. Key Actor Interviews to Inform Framework Design

- need to develop a monitoring framework that works within a governance context characterised by complexity and inter-connectedness;

- value in supporting all actors and agencies to come together to jointly build an agreed understanding of the Reef 2050 Plan governance system and develop a platform for taking shared approaches to continuous improvement of the system; and

- need to include particular attributes and/ or indicators in the monitoring framework, for example, connectivity, transparency, and coherence.

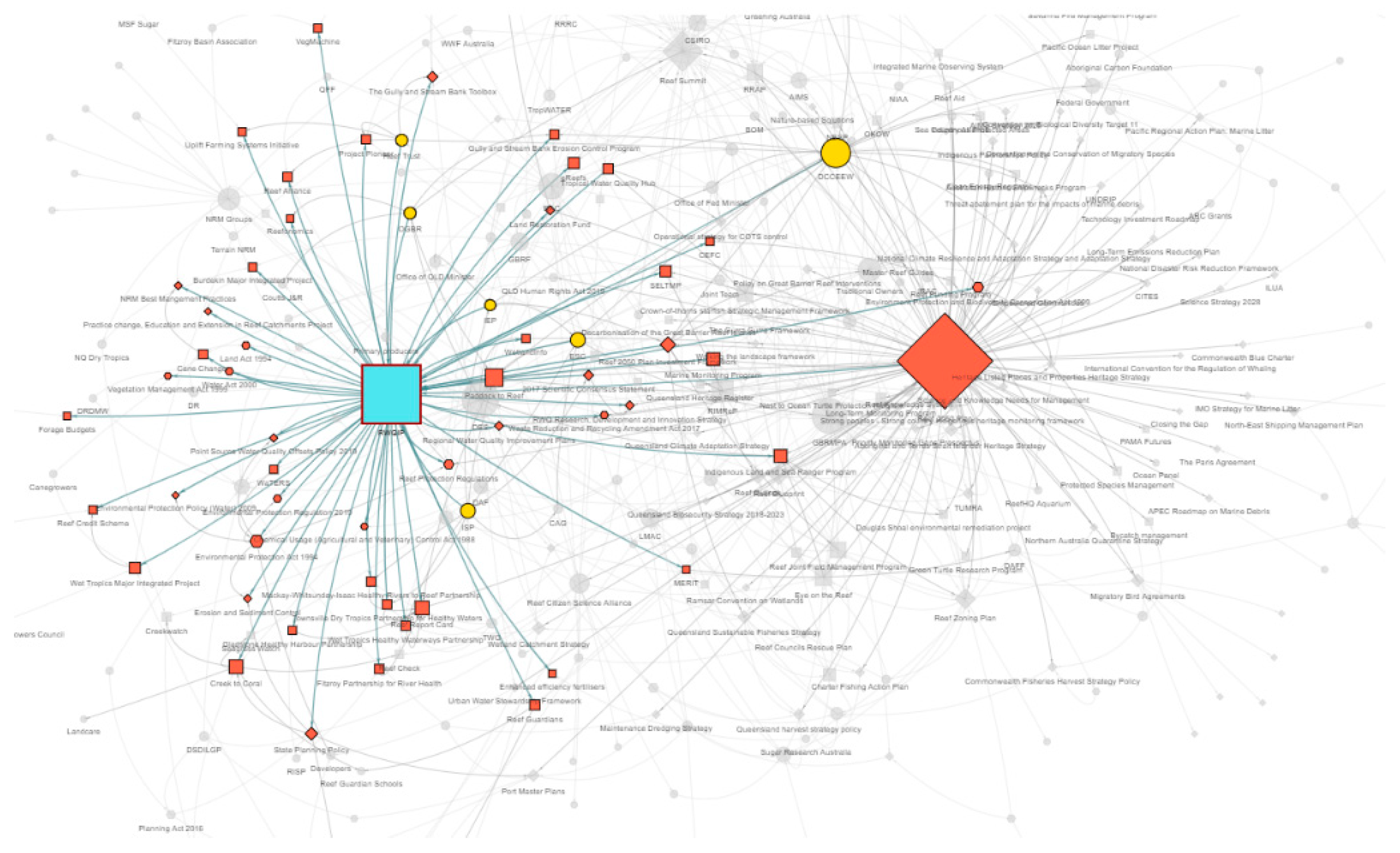

2.1.3. Reef Governance Network Mapping

2.1.4. Interviews, Focus Groups, Steering Committee and Technical Working Group Inputs

2.1.5. Theory of Change

2.1.5. Finalising the Framework

- We developed a preliminary monitoring framework and its attributes by combining the results from the literature review, the mapping exercise, and analysis of the first round participant interviews and focus group discussions.

- We then held two in-person workshops in two Queensland locations with sixteen diverse GBR actors and Traditional Owners to gain deeper perspectives on governance health and provide feedback on an emerging evaluation framework. A third online workshop was held to accommodate participants who could not attend in person. A further six conversations were held with members of the Reef 2050 Traditional Owner Steering Committee, and with the Project Steering Committee and the Technical Working Group for input and feedback.

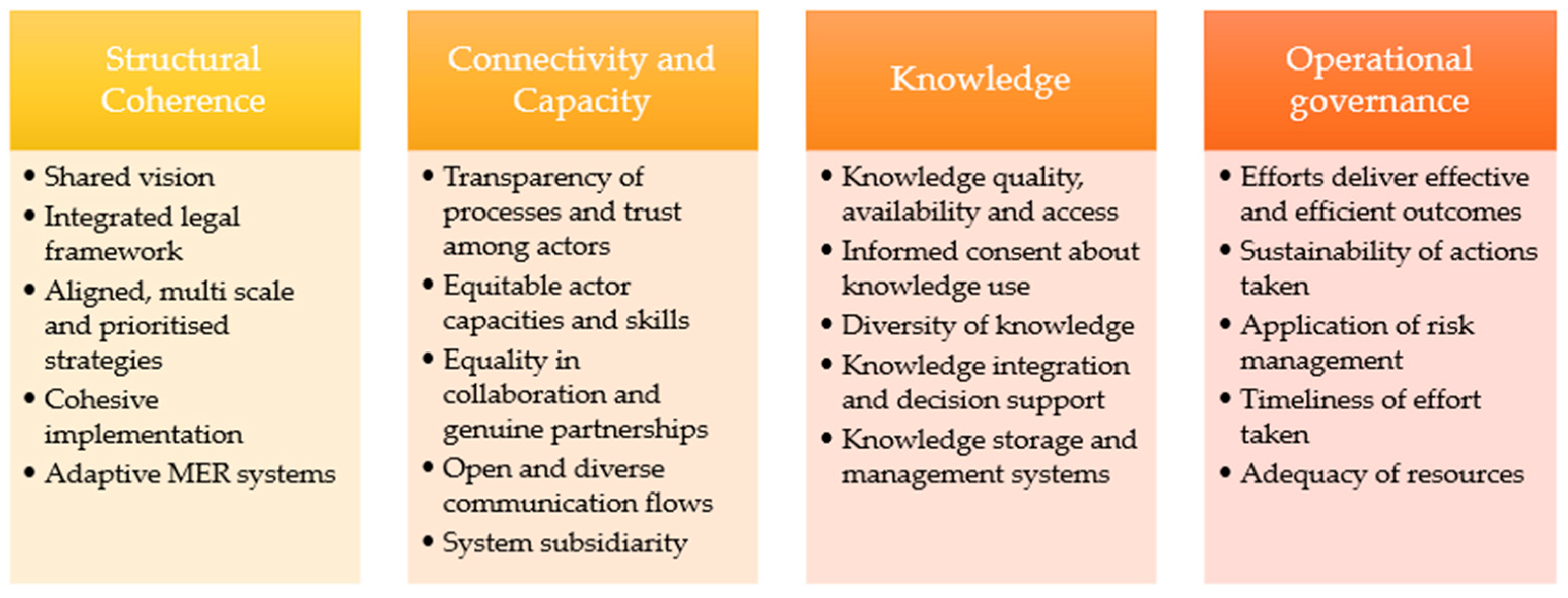

- We integrated the results of those conversations into emerging versions of the framework until we developed the final version. The latter consists of 20 attributes for a healthy governance system, grouped in four clusters: coherence, connectivity and capacity, knowledge, and operational governance. (See Consistent with GSA thinking, our proposed final version of the framework, presented in Figure 3.)

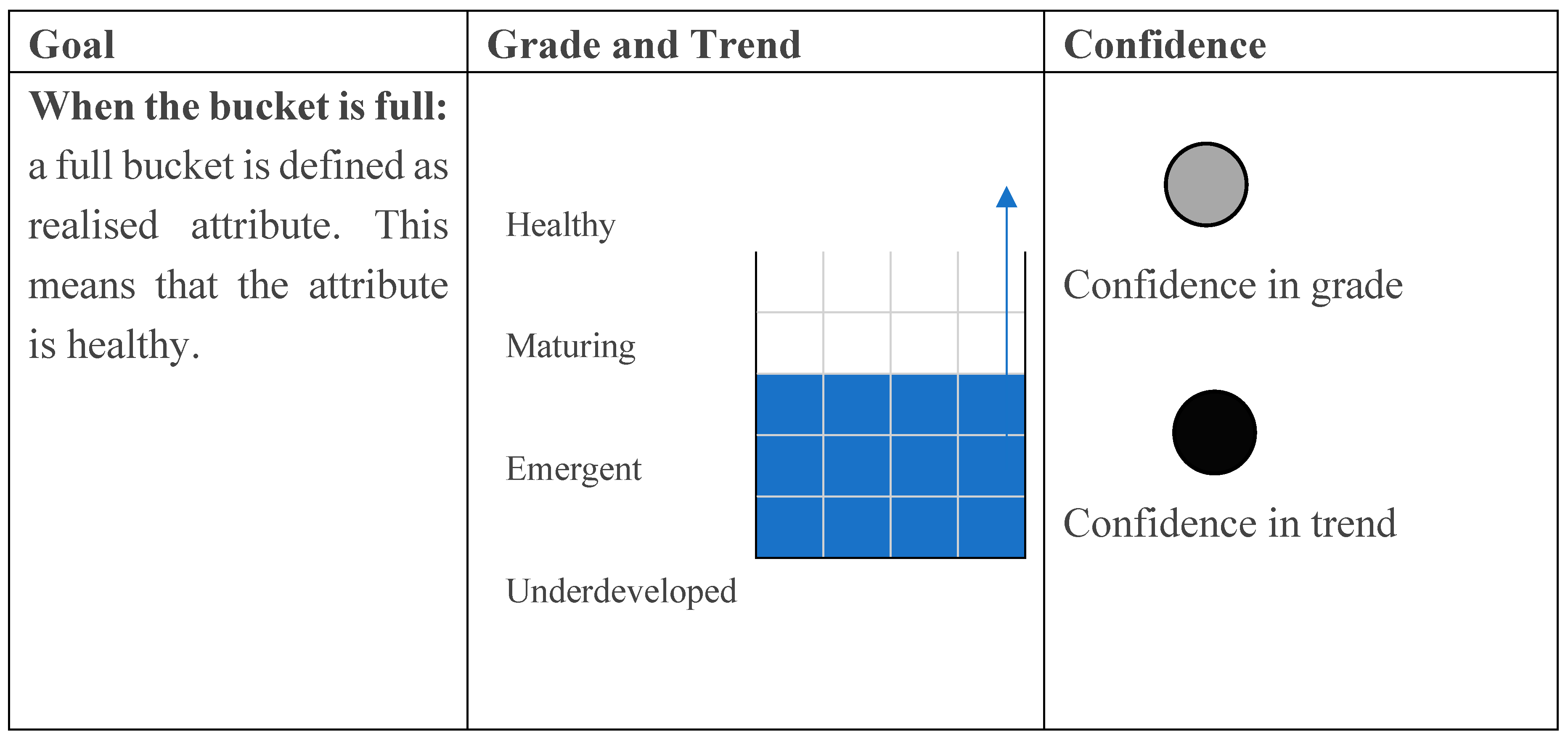

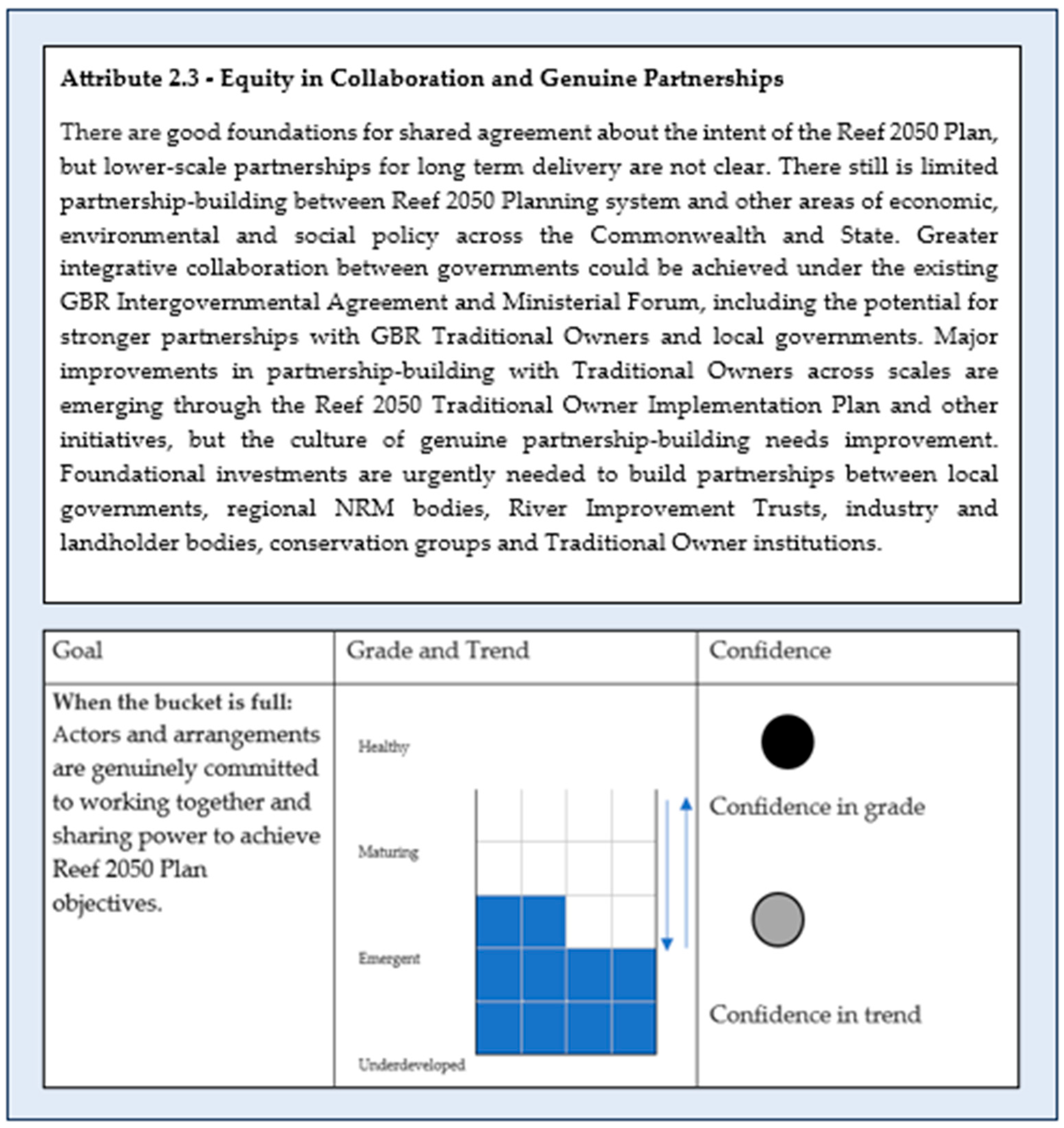

- To accompany the framework, and to be used in the assessment process, we developed a Likert scale to rate each attribute and provide narratives to support each score.

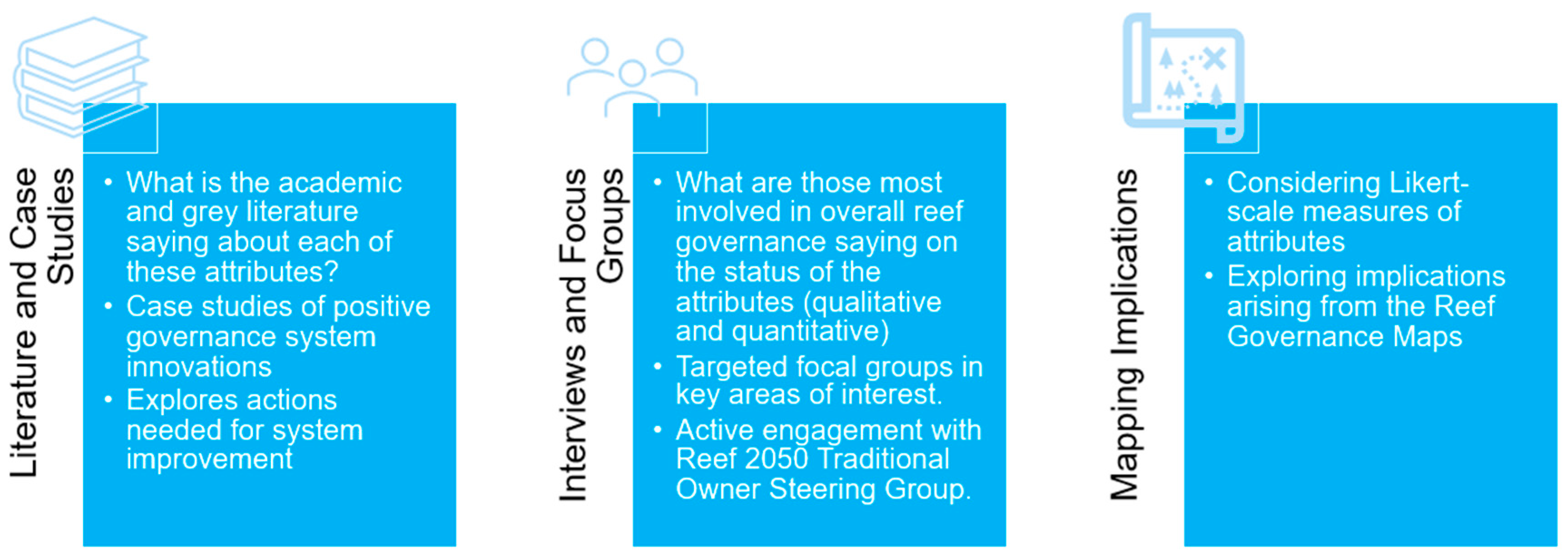

2.2. Applying Multiple Lines of Evidence for Benchmarking Against the Framework

- First, for each attribute, we conducted a literature scan that included international and Australian academic literature, government reports, policies, and consultancy documents. Although a scan of the international literature was important to develop attribute definitions and analysis on a larger scale, the main focus of this exercise has been on literature and documents related to the GBR, when possible;

- Second, we investigated case studies of governance practice in the context of the GBR related to each attribute. For example, in the case of ‘Shared Vision’, the first attribute in the ‘Coherence’ cluster of the framework, we explored the case of the 2022 Traditional Owner Implementation Plan. The latter is an example of how a shared vision for GBR governance was developed over time through collaboration and conversations on how to achieve the goal of a healthier and more resilient GBR; and

- We again invited deliberation with GBR experts through twenty in-depth interviews; three focus group discussions; and through the Steering Group and Technical Working group. Separate conversations were held with members of the Reef Traditional Owners Steering Committee. During the interviews participants used a Likert scale to rate each attribute (from healthy to unhealthy) and provided narratives to support their scores. Focus group participants were invited to review a draft consolidated evaluation derived from interviews, case studies and reviewed literature, and to discuss findings of the benchmark.

2.2.1. Data Visualisation and Reporting

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DESTI | Department of Environment, Science, Tourism and Innovation (Queensland) |

| DCCEEW | Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (Commonwealth) |

| GBR | Great Barrier Reef |

| GBRF | Great Barrier Reef Foundation |

| GBRMP | Great Barrier Reef Marine Park |

| GBRMPA | Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority |

| GSA | Governance Systems Analysis |

| IUCN | International Union for the Conservation of Nature |

| IUCN-WCPA | International Union for the Conservation of Nature - World Commission on Protected Areas |

| JCU | James Cook University |

| M&E | Monitoring and Evaluation |

| NGOs | non-governmental organisations |

| OUV | Outstanding Universal Value |

| Reef Authority | Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority |

| Reef 2050 Plan | Reef 2050 Long-Term Sustainability Plan |

| RIMReP | Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting |

| TO | Traditional Owner |

| QUT | Queensland University of Technology |

References

- Baldwin, E.; Thiel, A.; McGinnis, M.; Kellner, E. Empirical research on polycentric governance: Critical gaps and a framework for studying long-term change. Policy Studies Journal 2024, 52, 319–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Governance: What Do We Know, and How Do We Know It? Annual Review of Political Science 2016, 19, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bommel, S. Embracing collaborative research in political science in Australia and beyond. Australian Journal of Political Science 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M.; Julie, D.; Allan, C.; Elaine, S.; Griffith, R. Governance Principles for Natural Resource Management. Society & Natural Resources 2010, 23, 986–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldrup, S. How to measure governance: a new assessment tool. Oxford Policy Management 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkki, S.; Jokinen, M.; Nijnik, M.; Zahvoyska, L.; Abraham, E.M.; Alados, C.L.; Bellamy, C.; Bratanova-Dontcheva, S.; Grunewald, K.; Kollar, J.; et al. Social equity in governance of ecosystem services: Synthesis from European treeline areas. Climate Research 2017, 73, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouki, A.; Mellouli, S.; Daniel, S. Understanding issues with stakeholders participation processes: A conceptual model of SPPs’ dimensions of issues. Government Information Quarterly 2022, 39, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzer, K. Picking up speed: public participation and local sustainability plan implementation. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2018, 61, 1594–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, N.; Rydin, Y. What Can Social Capital Tell Us About Planning Under Localism? Local Government Studies 2013, 39, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondizio, E.S.; Ostrom, E.; Young, O.R. Connectivity and the Governance of Multilevel Social-Ecological Systems: The Role of Social Capital. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2009, 34, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; van Riper, C.J.; Leitschuh, B.; Bentley Brymer, A.; Rawluk, A.; Raymond, C.M.; Kenter, J.O. Social learning as a link between the individual and the collective: evaluating deliberation on social values. Sustainability Science 2019, 14, 1323–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.; Storr, V. Social capital facilitates emergent social learning. The Review of Austrian Economics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, C.M. Deliberative governance in the context of power. Policy and Society 2009, 28, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S. Foundations and Frontiers of Deliberative Governance; Oxford University Press: 2010.

- Dryzek, J.S.; Pickering, J. Deliberation as a catalyst for reflexive environmental governance. Ecological Economics 2017, 131, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Poudel, S.; York, A. Governance of protected areas: an institutional analysis of conservation, community livelihood, and tourism outcomes. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2022, 30, 2686–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.; Dudley, N.; Hockings, M.; Holmes, G.; Laffoley, D.; Stolton, S.; Wells, S.; Wenzel, L. Guidelines for applying the IUCN protected area management categories to marine protected areas. Second edition; IUCN: Gland. Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leverington, A.; Hockings, M.; Leverington, F.; Trinder, C.; Polglaze, J. Independent assessment of management effectiveness for the GBR Outlook Report 2019; Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority: 2019.

- Hockings, M.; Leverington, F.; Cook, C. Protected area management effectiveness. Protected area governance and management 2015, 889–928. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C.; Malekpour, S.; Mintrom, M. Cross-scale, cross-level and multi-actor governance of transformations toward the Sustainable Development Goals: A review of common challenges and solutions. Sustainable Development 2023, 31, 1250–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Global Environmental Change 2009, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, B. Collaborative governance assessment; Worldfish: Penang, Malaysia, 2012; Volume Guidance Note: AAS-2012-27.

- Glass, L.-M.; Newig, J. Governance for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: How important are participation, policy coherence, reflexivity, adaptation and democratic institutions? Earth System Governance 2019, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, M. Technocratic and deliberative governance for sustainability: rethinking the roles of experts, consumers, and producers. Agriculture and Human Values 2020, 37, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckstrand, K. Civic Science for Sustainability: Reframing the Role of Experts, Policy-Makers and Citizens in Environmental Governance. Global Environmental Politics 2003, 3, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F. Citizens, Experts, and the Environment: The Politics of Local Knowledge; Duke University Press: 2000.

- Rohracher, H.; Coenen, L.; Kordas, O. Mission incomplete: Layered practices of monitoring and evaluation in Swedish transformative innovation policy. Science and Public Policy 2023, 50, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Reef Authority. Great Barrier Reef Blueprint for Climate Resilience and Adaptation; The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority: Townsville, 2024.

- Taylor, J.; Litchfield, C.; Le Busque, B. Australians’ perceptions of species diversity of, and threats to, the Great Barrier Reef. Marine and Freshwater Research 2025, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockie, S.; Bartelet, H.A.; Ritchie, B.W.; Demeter, C.; Taylor, B.; Sie, L. Australians support multi-pronged action to build ecosystem resilience in the Great Barrier Reef. Biological Conservation 2024, 299, 110789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, E.; Huggins, A. Chapter 20: Climate change litigation before the World Heritage Committee: subject to negotiation? Research Handbook on Climate Change Litigation. Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 384–402.

- Hamman, E. Governing the great barrier reef: Australia’s obligations under the world heritage convention. Precedent (Sydney, N.S.W.) 2021, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley, K.M.; Baird, A.H. Future climate warming threatens coral reef function on World Heritage reefs. Global Change Biology 2024, 30, e17407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, A.; Vella, K.; Pressey, R.; Brodie, J.; Yorkston, H.; Potts, R. A method for risk analysis across governance systems: a Great Barrier Reef case study. Environmental Research Letters 2013, 8, 015037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douvere, F.; Badman, T. Reactive monitoring mission to the Great Barrier Reef (Australia): mission report. 2012.

- Australian Government; Queensland Government. Reef 2050 plan - implementation strategy; 2015.

- Commonwealth of Australia. Reef 2050 Long-Term Sustainability Plan 2021–2025. 2023.

- Dale, A.; Wren, L.; Fraser, D.; Talbot, L.; Hill, R.; Evans-Illidge Libby; Forester Traceylee; Winer Michael; George Melissa; Gooch, M.; et al. Traditional Owners of the Great Barrier Reef: the next generation of Reef 2050 actions; Australian Government Canberra, 2018.

- Reef 2050 Traditional Owner Steering Group. Traditional Owner Implementation Plan.; 2022.

- REEFTO. Traditional Owner Implementation Plan. Available online: https://reefto.au/ (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Dale, A.; Vella, K.; Pressey, R.L.; Brodie, J.; Yorkston, H.; Potts, R. A method for risk analysis across governance systems: a Great Barrier Reef case study. Environmental Research Letters 2013, 8, 015037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, L.H.; Lemos, M.C.; Margules, C.; Barnes, M.L.; Song, A.; Morrison, T.H. Divergence over solutions to adapt or transform Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. npj Climate Action 2024, 3, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooch, M.; Dale, A.; Marshall, N.; Vella, K. Assessment and monitoring of the human dimensions within the Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program: final report of the Human Dimensions Expert Group. 2019.

- The Reef Authority. Reef 2050 integrated monitoring and reporting program strategy. 2015.

- Dale; Vella, K.; Pressey, R.; Brodie, J.; Gooch, M.; Potts, R.; Eberhard, R. Risk analysis of the governance system affecting outcomes in the Great Barrier Reef. Journal of Environmental Management 2016, 183, 712–721. [CrossRef]

- Day, J.C.; Dobbs, K. Effective governance of a large and complex cross-jurisdictional marine protected area: Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Marine Policy 2013, 41, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Vella, K.; Gooch, M.; Potts, R.; Pressey, R.; Brodie, J.; Eberhard, R. Avoiding Implementation Failure in Catchment Landscapes: A Case Study in Governance of the Great Barrier Reef. Environmental Management 2018, 62, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.L.; Datta, A.; Morris, S.; Zethoven, I. Navigating climate crises in the Great Barrier Reef. Global Environmental Change 2022, 74, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera-Garcia, J.; Neil, S. Examining how collaborative governance facilitates the implementation of natural resource planning policies: A water planning policy case from the Great Barrier Reef. Environmental Policy and Governance 2020, 30, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, K.; Dale, A.; Calibeo, D.; Limb, M.; Gooch, M.; Eberhard, R.; Babacan, H.; McHugh, J.; Baresi, U. Monitoring the governance system underpinning the implementation and review of the Reef 2050 Plan: A preliminary benchmark; Great Barrier Reef Foundation (GBRF): Brisbane, 2024; p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin, A.K.; Kotaman, H. The epistemological perspectives on action research. Journal of Educational and Social Research 2013, 3, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, L.; Phinney, A.; Chaudhury, H.; Rodney, P.; Tabamo, J.; Bohl, D. Appreciative Inquiry:Bridging Research and Practice in a Hospital Setting. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2018, 17, 1609406918769444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Vella, K.; Potts, R. Governance Systems Analysis (GSA): A Framework for Reforming Governance Systems. Journal of Public Administration and Governance; Vol 3, No 3 (2013) 2013. [CrossRef]

- Morita, K.; Okitasari, M.; Masuda, H. Analysis of national and local governance systems to achieve the sustainable development goals: case studies of Japan and Indonesia. Sustainability Science 2020, 15, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, D.; Cooney, R.; Roe, D.; Dublin, H.T.; Allan, J.R.; Challender, D.W.; Skinner, D. Developing a theory of change for a community-based response to illegal wildlife trade. Conservation Biology 2017, 31, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinholz, D.L.; Andrews, T.C. Change theory and theory of change: what’s the difference anyway? International Journal of STEM Education 2020, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.K.; Schuetz, T.; Förch, W.; Cramer, L.; Abreu, D.; Vermeulen, S.; Campbell, B.M. Responding to global change: A theory of change approach to making agricultural research for development outcome-based. Agricultural Systems 2017, 152, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funnell, S.C.; Rogers, P.J. Purposeful program theory: Effective use of theories of change and logic models; John Wiley & Sons: 2011.

- Alvarez-Robinson, S.M.; Arms, C.; Daniels, A.E. The social, emotional and professional impact of using appreciative inquiry for strategic planning. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, V. Collaborative Governance for Sustainable Development. In Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions; Leal Filho, W., Marisa Azul, A., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Özuyar, P.G., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Day, J.C. Key principles for effective marine governance, including lessons learned after decades of adaptive management in the Great Barrier Reef. Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollagher, M.; Hartz-Karp, J. The Role of Deliberative Collaborative Governance in Achieving Sustainable Cities. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2343–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewatsch, S.; Kennedy, S.; Bansal, P. Tackling wicked problems in strategic management with systems thinking. Strategic Organization 2023, 21, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| If … | Then… | Has the Impact of | Contributes to Transformation and Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| If we understand how governance attributes operate including strengths and risks | We see the strategic importance of different attributes We understand the way different knowledges are applied Have insight into decision making capacity and processes of different actors |

Better decision-making capacity in each attribute Addressing the gaps, contradictions, and alignments within and between attributes |

Healthy integrated governance systems to manage the Reef 2050 Plan governance system Jointly determined strategic multi-scale outcomes are achieved and sustained over time Impact and outcomes are measured across the governance system and iterative learning supports governance health |

| If there is integration/connectivity across different governance attributes | Overall governance integrity is achieved with alignment of attributes within the complex system Adaptive use and management of diverse knowledge sets is more likely to occur |

Common strategic vision and aligned multi-scale strategies are achieved Joint science/knowledge priorities are determined, knowledge integration is achieved System wide coordinated planning and cohesive action and implementation are achieved Improved accountability and transparency are achieved |

|

| If there is wide genuine GBR actor participation in improving the health of the Reef 2050 Plan governance system | There is improved understanding of the role and contribution of different actors Strengths/weaknesses of connectivity among actors are identified in governance systems |

Improved connectivity within and between key decision making institutions and sectors Genuine partnerships for system improvement emerge Improved trust across actors is achieved Capacity of actors for GBR governance is improved |

|

| If we situate the Reef 2050 governance system into the wider governance systems | Line of sight across the whole governance system impacting GBR outcomes improves Better risk assessment is enabled |

Mitigates risk of system failures across the whole governance system or specific attributes Enables adequate resources and efficiency outcomes for planning and implementation Provides line of sight for improving effectiveness in outcomes across the system |

|

| If the Reef 2050 governance system can effectively undertake monitoring, learning and governance systems reform | The evidence base for iterative governance is improved Continuous observations of the governance systems spanning strategy and implementation are enabled |

Improved adaptive governance capacity of key decision making institutions & sectors Learning informs adaptive governance system reform |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).