1. Introduction

Hand hygiene represents a long-standing issue that is subject to constant debates and improvements, but it is higly relevant nowadays as well. Although it has been studied and proven to be a useful and effective strategy that contributes to personal and social health, it has not yet been implemented in life aspects.

The aim of this study is identifying the potential hand hygiene problems among children and adolescents from disadvantaged families in Timis County and formulate proper solutions for their benefit, focusing on hygiene practices.

According to the World Health Organization, hygiene represents the conditions and practices that promote health and prevent pathigens spread. Hygiene therefore includes specific practices that are useful for health protection. These practises are: environment cleaning, equipment sterlisiation, hand disinfection, water purification and safe waste disposal [

1].

The first defense line against pathogens and toxins is represented by skin, the largest human organ, in a dynamic state that is constantly influenced by internal factors and external factors exposure. These internal and external factors can alter the skin microbiome. Non-pathogenic bacteria colonise the human skin. Skin microbiome is still underrepresented or reported as culture-based studies have their limitations [

2].

The epidermis is populated by bacterial, fungal and parasitic species and viruses, most of these being harmless. Structurally, the epidermis is resistant to toxins and the micro-organisms penetration and retains water and nutrients.

Contaminated hands are susceptible to microbial invasion. The factors that influrnce contaminants concentration are: source of conatmination, soil type or dust, pathogen type, skin hydration, and inoculation [

3]. Hand diseases can be transmitted through contact with the environment or with other people. Transmission usually occurs when food or drinks are prepared with unwashed hands, if there has been contact with contaminated surfaces by touching the eyes, nose, or mouth [

4,

5].

Several studies found that drying hands with paper towels has been shown to increase the number of resistant bacteria, including potentially pathogenic bacteria, compared to air drying [

6,

7].

It is estimated that only 19% of people worldwide handwash with soap and water after exposure to feces, these representign worrying figures [

8]. Knowledge on handwashing benefits are though widespread. For instance, in Kenya, 92% of respondents knew that hand germs can cause diarheea. However, in studies conducted in several countries such as India, Ghana, China, Bangladesh and Kenya, only between 2 and 29% of participants declared washing their hands with soap after defecation or after using the toilet, even in the United Kingdom where water, soap and sanitary conditons are avaialble at a larger scale [

8,

9].

Hand hygiene has a direct impact on health and has a direct link with the availability of soap and water. UNICEF estimates that only 51% of primary schools in 60 low-income countries have access to proper sanitary conditions. An alternative to overcome the challenges of limited water supply availability and boost the efforts to ensure hand hygiene is using hand sanitizer when water is not available [

9].

Educating on good hygiene habits among adults and children represents an important public health goal. As pathogens can survive in both human body and the environment, more effective campaigns should promote personal hygieneas well as environment health (e.g., surface cleaning) [

9,

10].

Hand washing prevents 1 in 3 intestinal infections and 1 in 5 respiratory diseases. Parents and guardians play a key role in educating children to wash their hands from a young age to develop a healthy habit for a lifetime [

9,

10].

Good hygiene practices and a clean, safe environment are essential pillars of the health, development and children well-being [

10]. These factors are particularly relevant in institutional care facilities of orphaned & abandoned children, in vulnerable populations whose basic needs are often not met [

10].

Several studies have proved that children from daycare centers are more prone to have a poorer personal hygiene, due to inadequate water supply, unproper sanitation and and overcrowding of hygiene facilities. Parasites, bacteria and diarrheal diseases in hospitalized children are highly associated with poor hygiene [

11,

12].

Children play an important role in disease due to closer physical contact compared to other agea cathegories, so decreasing infection rates among children is associated with increased health benefits for a society [

13].

Pneumonia and diarhhea are 2 most common causes of infantile death worldiwide, representing more than 3.5 milion deaths per years in children younger than 5 years old, deaths that could have been preveted with a better hygienes [

11].

The main goal of this study is observing the hygiene behaviour of children from defavourised areas such as: families with unproper living conditions or foster care centres, aiming to analyse the education level in regard to methods to avoid infections and social exclusion due to poor hygiene.

We also analysed the correlation between poor hygiene practices and the prevalence of respiratory & digestive infections among children as well as the impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on hand hygiene & disinfection.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper constitues a descriptive and retrospective study involving 86 people who completed a proposed questionnaire. The statistical analysis examined data on hand hygiene among young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. The study participants were children and young people from daycare centers as well as people from families with poor living conditions.

Our questionnaire included 20 single or multiple choices questions, formulated in a way that young people could easily understand and answer the items. The first questions reffered about demographic information, including age, gender and location. The living environment was highly important as it represents the place where youngsters learn and analyze hygiene practices. The adolescents were asked hand hygiense rules and whether they had noticed their parents or health care workers washing their hands.

The frequency and lenght of hand washing represented another important item as well as the use soap or plain water for washing or the drying. In addition, information about hand hygiene before eating or after using the toilet and the access to running water and toiletts in the living environment.

In addition, the presence of respiratory symptoms and diarrhea, the variety of episodes, and the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on handwashing and disinfection practices were examined.

Statistical Data Analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and compared using Student’s T test. Distribution variables were presented as percentages and/or ratios and compared using the Pearson chi-square test. All statistical analyses, including odds ratios (OR), were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 20. All statistical tests were 2-tailed and the P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Statistical Analysis of Demographic Data

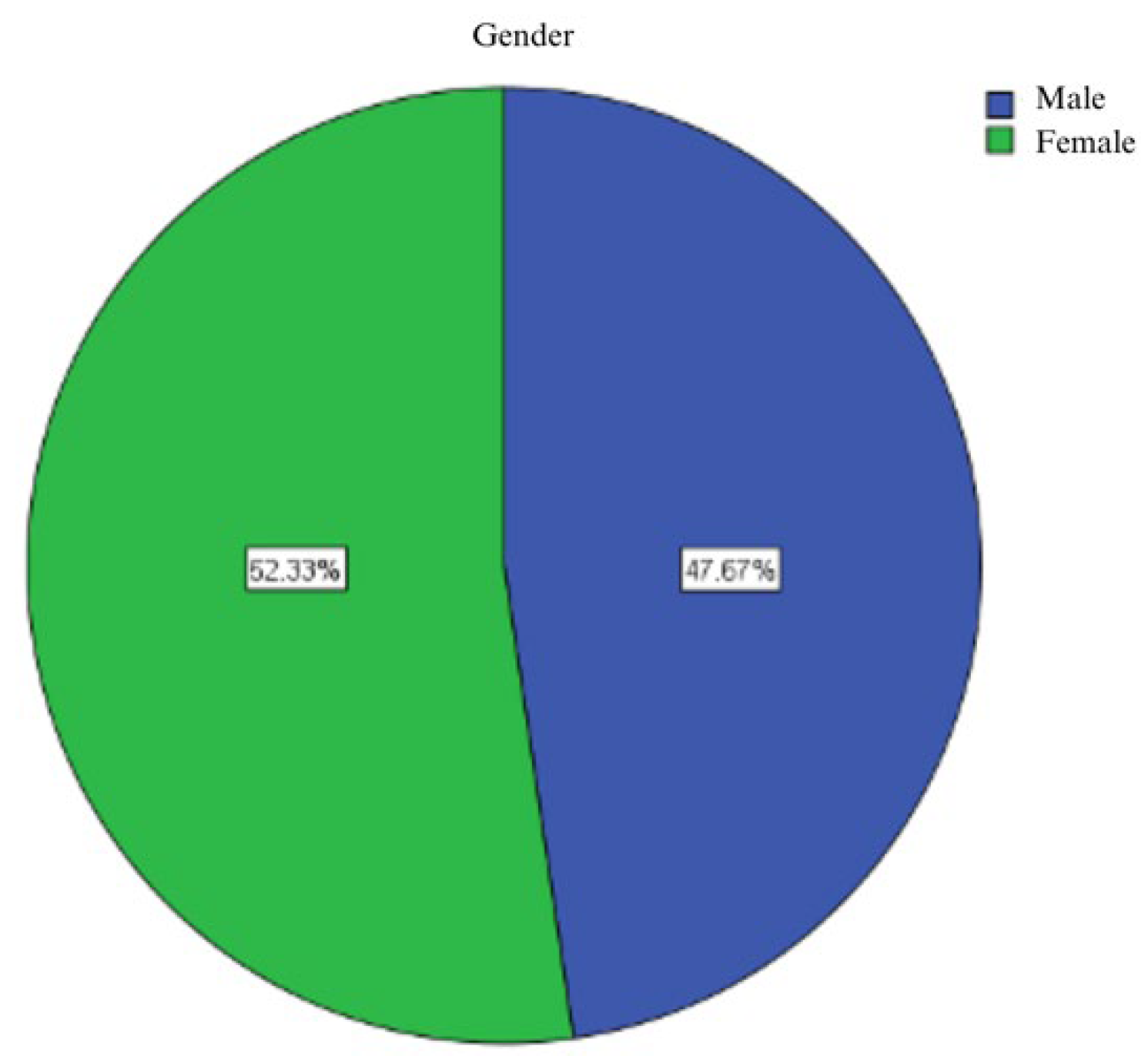

The age and gender of 86 participants were 2 of the demographic parameters we analyzed. As

Figure 1 indicates, regarding the gender, 52.3% of cases were female (45 cases) and only 47.7% (41 cases) were male (p-value 0.051)

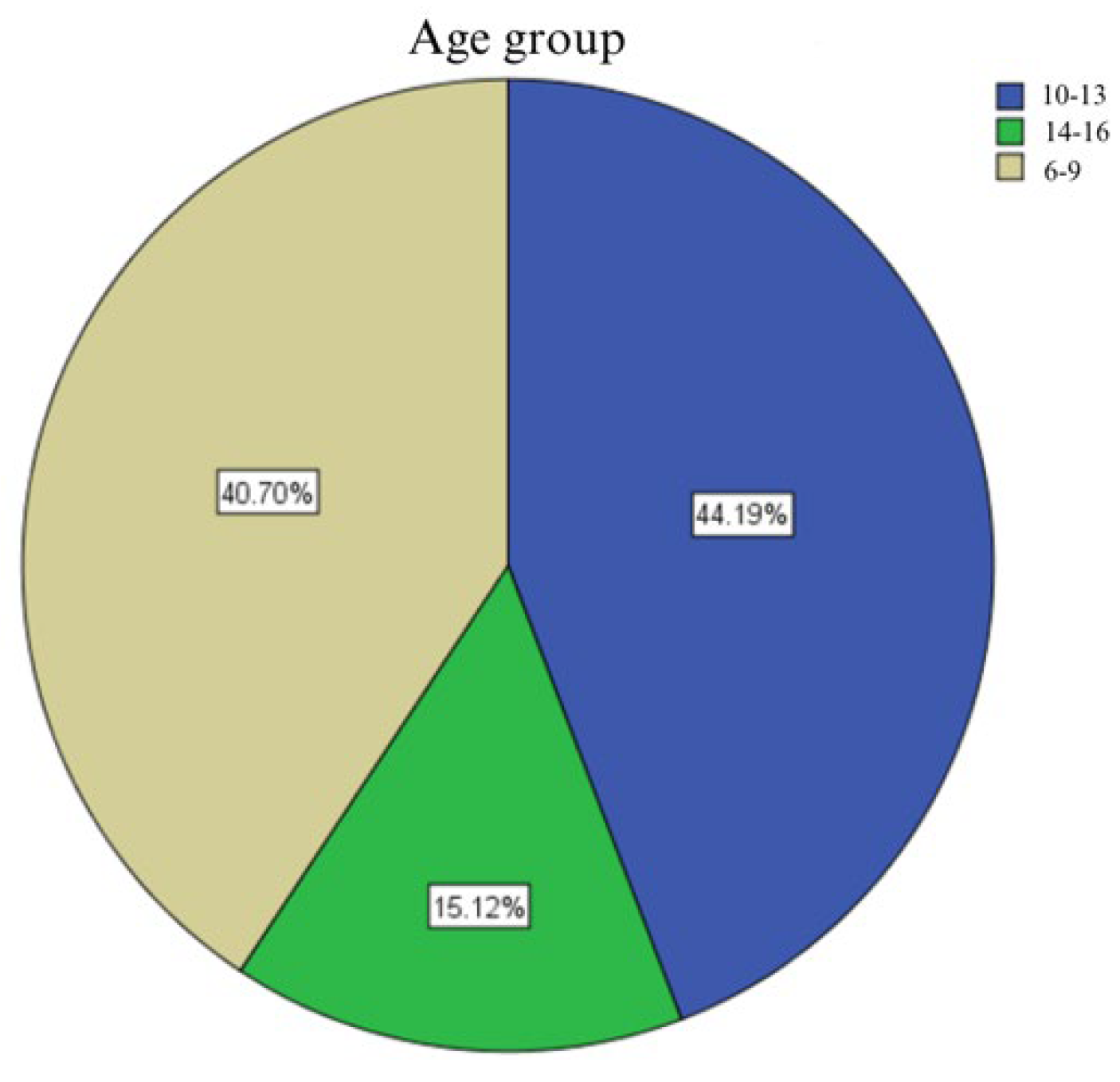

As for the distribution of the population by age, in

Figure 2, the statistical analysis of our subjects were aged between 10 and 13 years (38 cases, 44.2%) Most participants were aged between 6 and 9 years old (35 cases, 40.7%) (p-value 0.022). This information was summerised in

Figure 2.

3.2. Statistic Analysis of Living Conditions

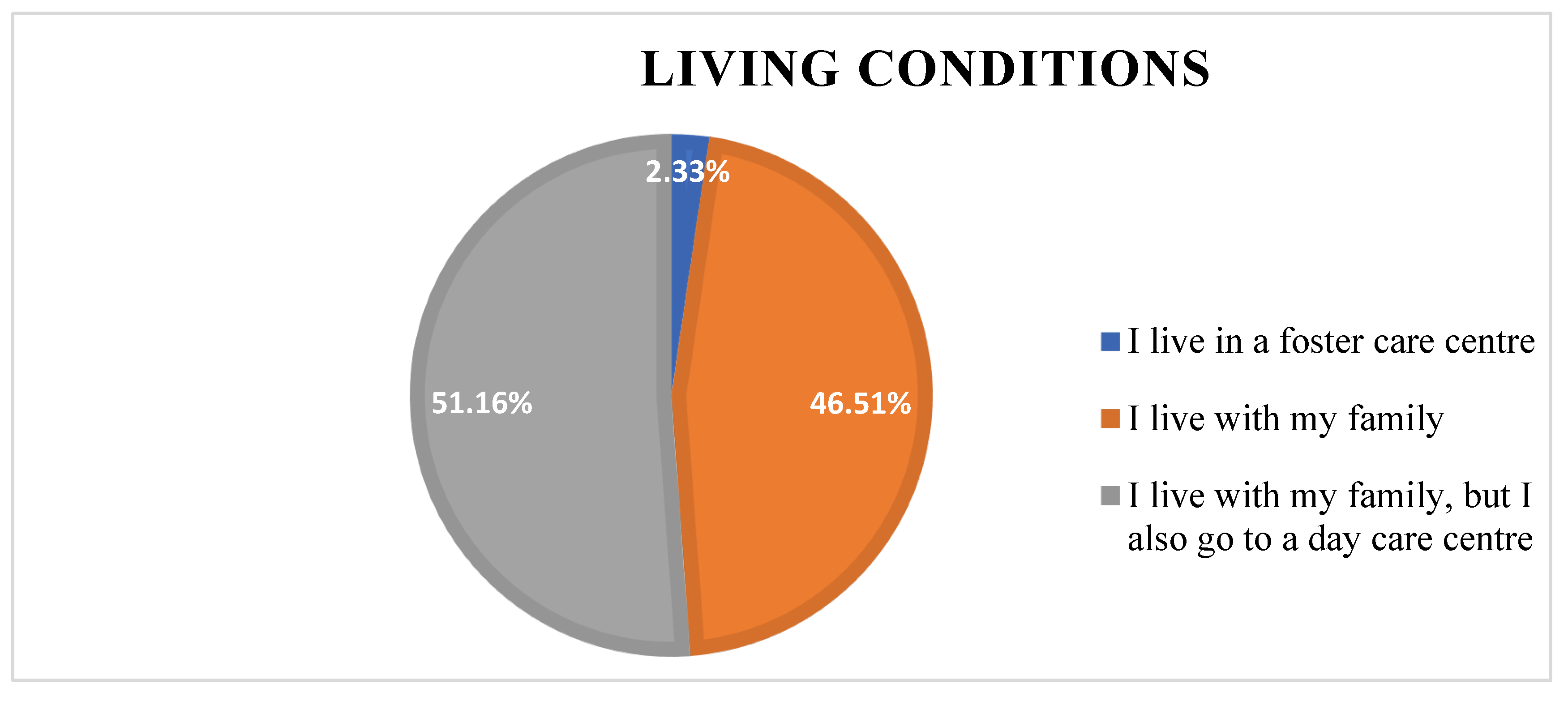

As

Figure 3 indicates, about 50% of the survey participants declared living with their family (44 cases, 51.2%), while 46.5% of participants lived with family but also interacted with day-centres in the same day (40 cases) (p-value 0.097);

3.3. Education Received from Parents/Care-Takers

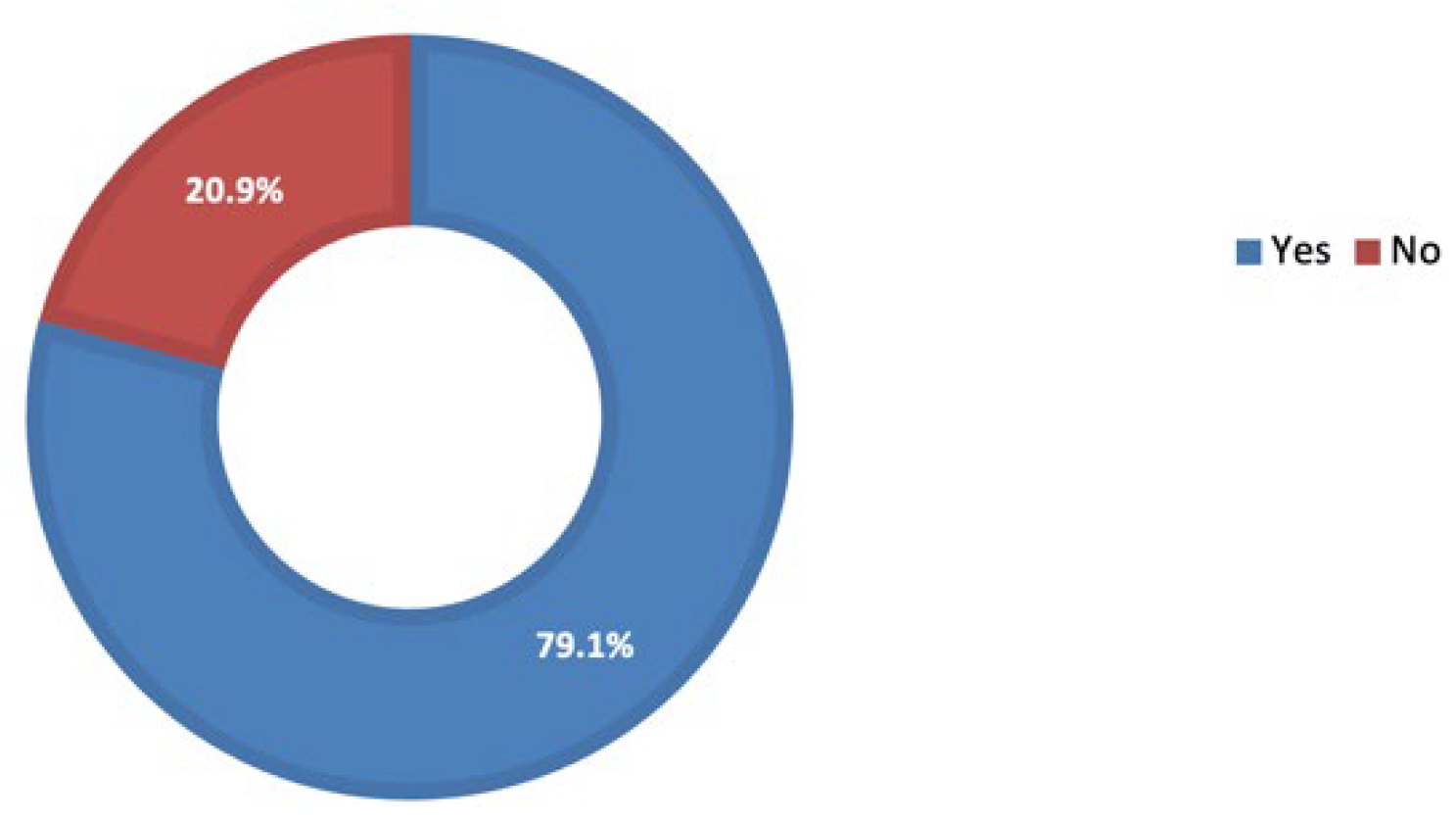

As

Figure 4 shows, approximately 80% of subjects were trained on adequate hand hygiene (68 cases, 79.1%) (p-value 0.008).

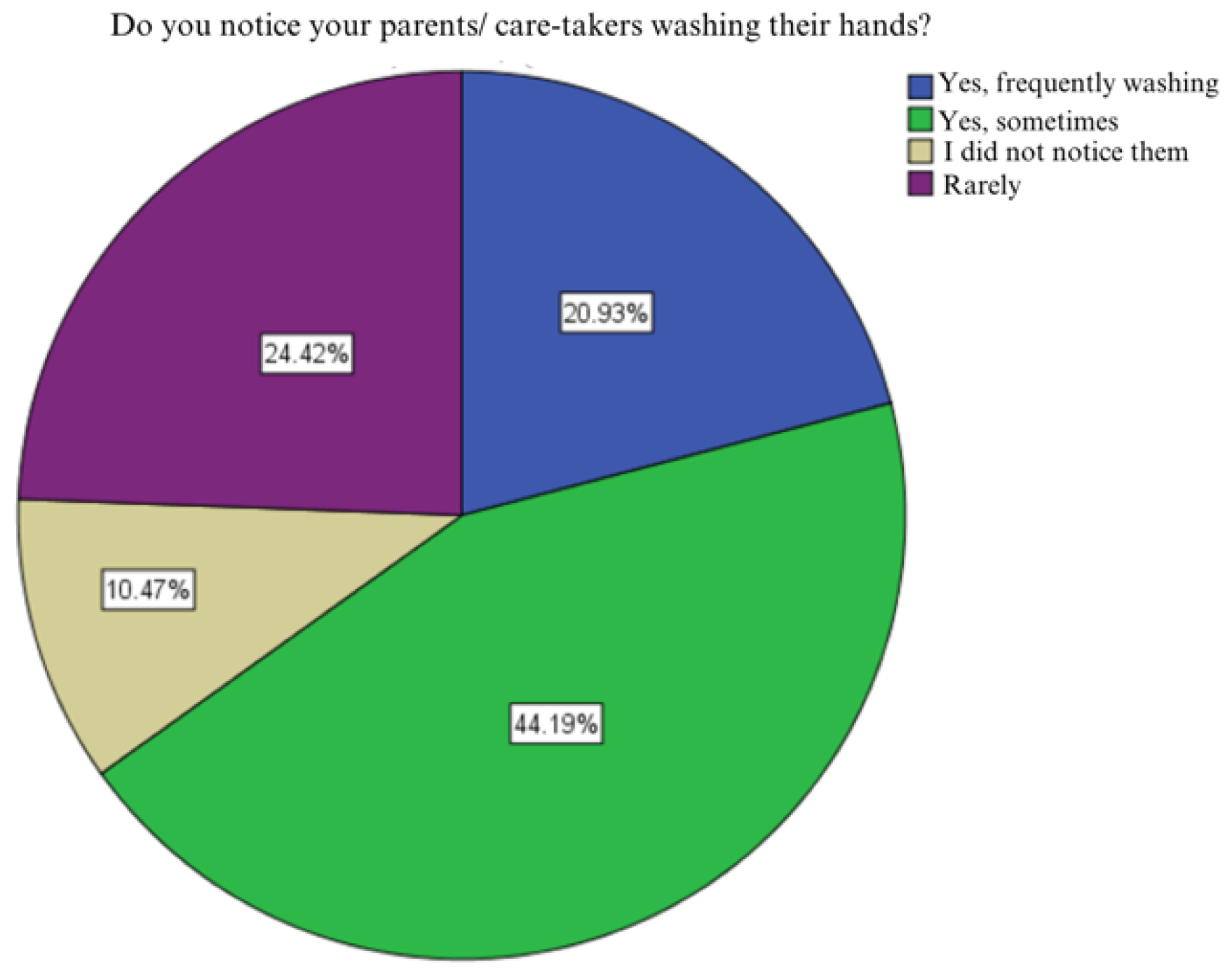

3.4. Hand Washing Habits of Parents/Care-Takers

As

Figure 5 indicates, 44.2% of participants reported that they sometimes noticed their parents or care-takers wahisng their hands (38 cases), followed by those who rarely see it (21 cases, 24.4%) (p statistic 0.007).

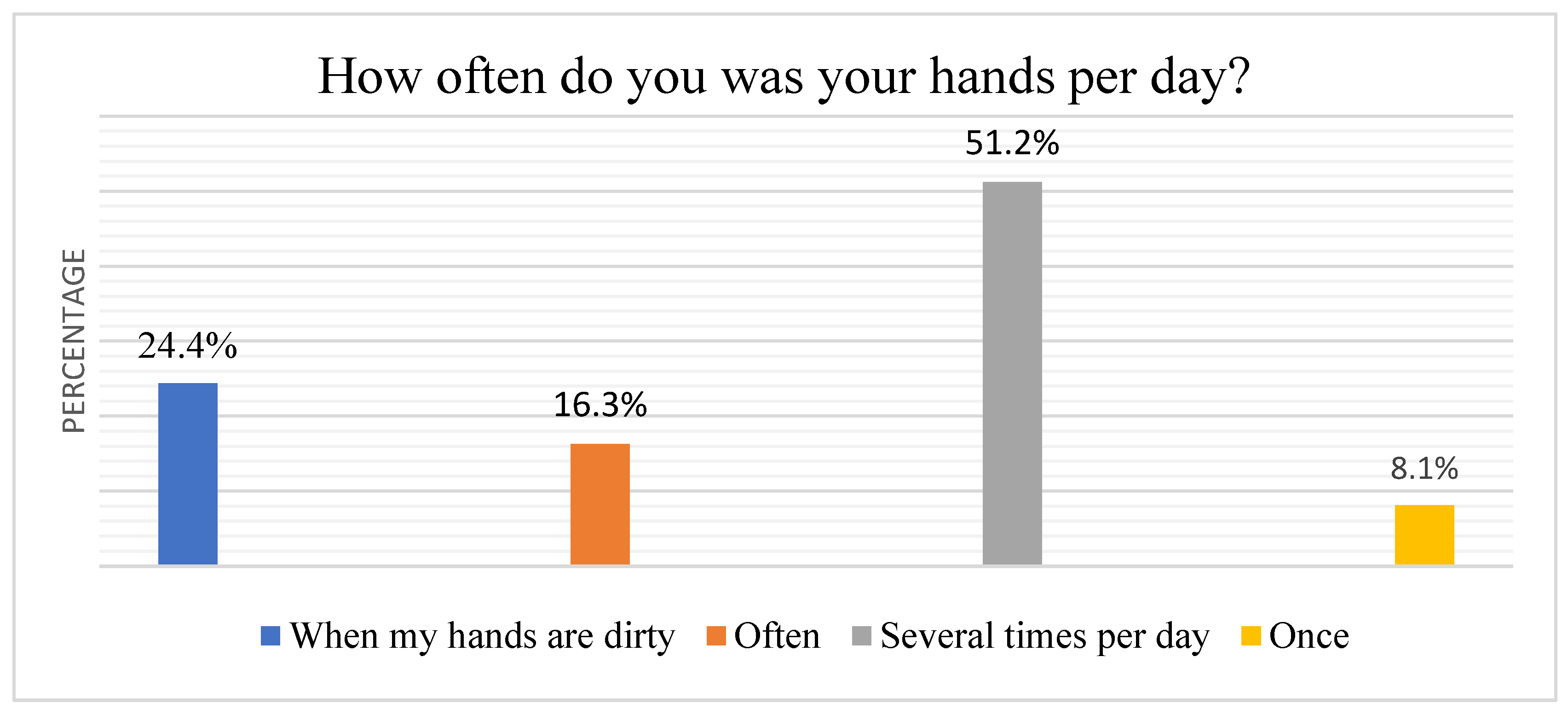

3.5. Hand Washing Habits of Subjects

51.2% of subjects wash their hands several times a day (44 cases, 51.2%), percentage followed by those who only do it so when their hands are dirty (21 cases, 24.4%), 16.3% wash their hands often and 8.1% once a day (p-value 0 .018) as seen in

Figure 6.

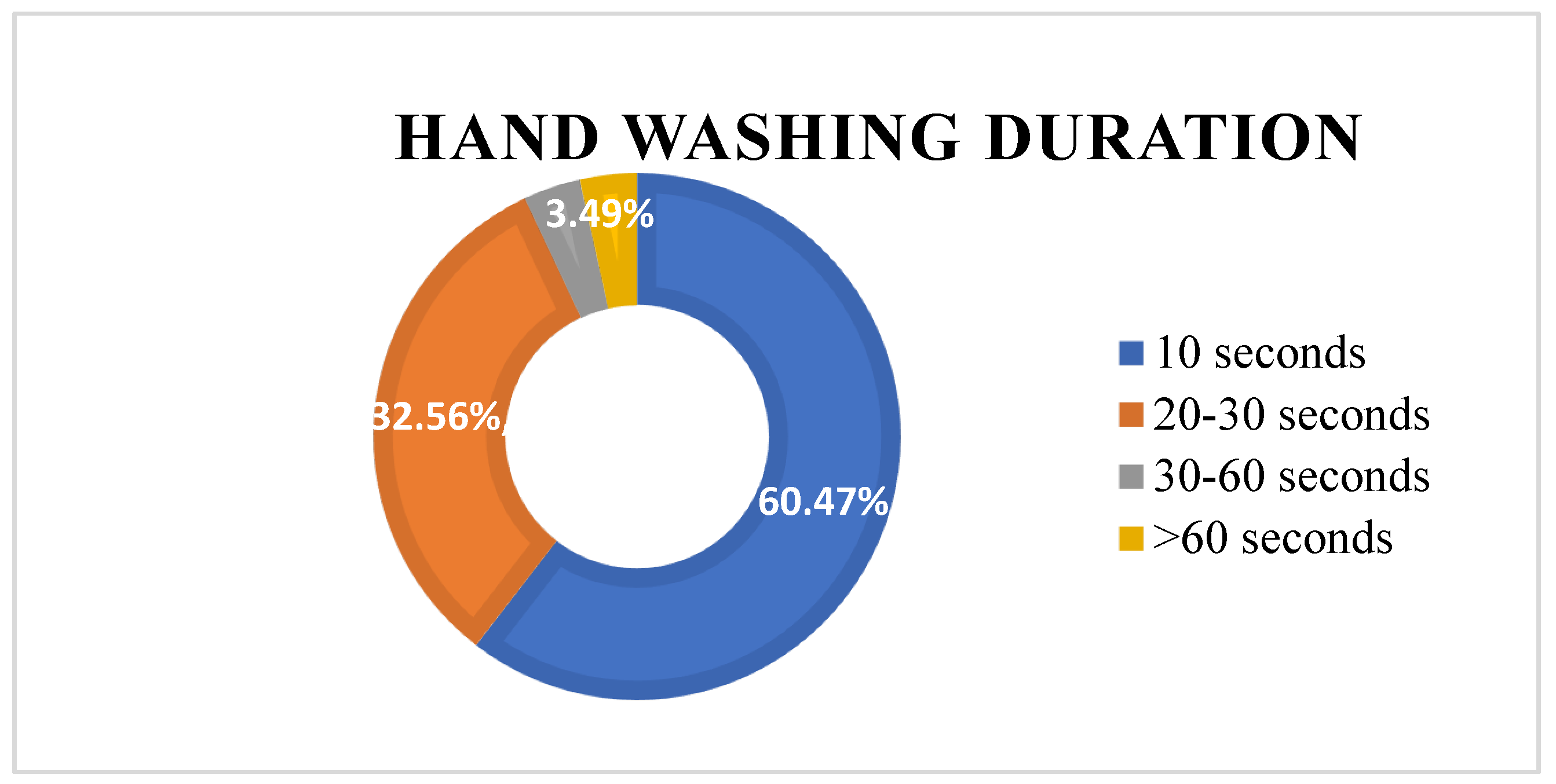

3.6. Duration of Hand Washing

Figure 7 shows that 60.5% of respondents needed up to 10 seconds (52 cases), followed by 20 to 30 seconds (28 cases, 32.6%) (p-value 0).036) (p-value 0.036) (

Figure 7).

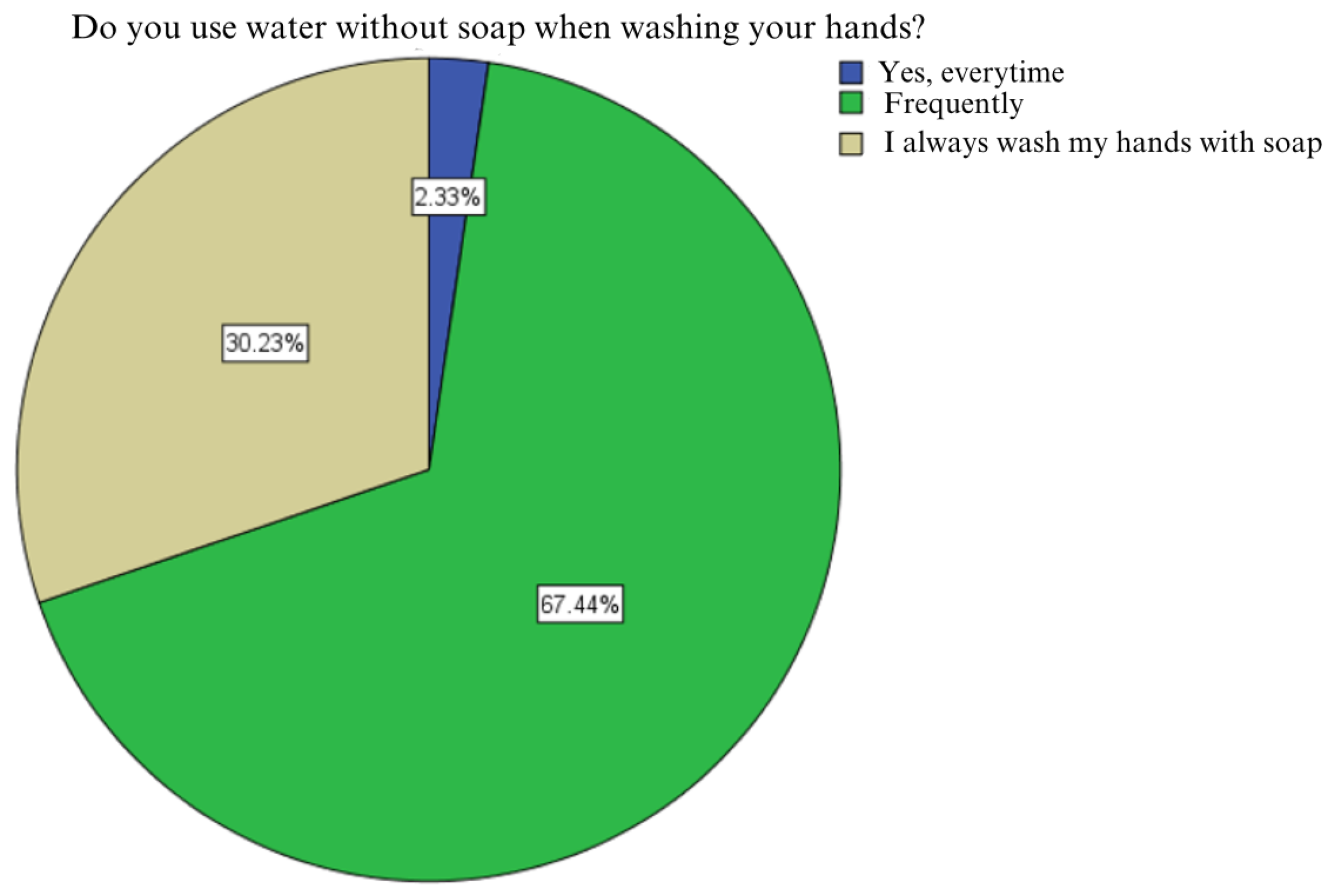

3.7. Using Water Without Soap

As

Figure 8 shows, 67.4% of respondents only use soap-free water (58 cases) (p-value 0.0).067) (

Figure 7) 67,4% dintre subiecţi folosesc frecvent doar apă, fără săpun (58 cazuri). (p statistic 0,067).

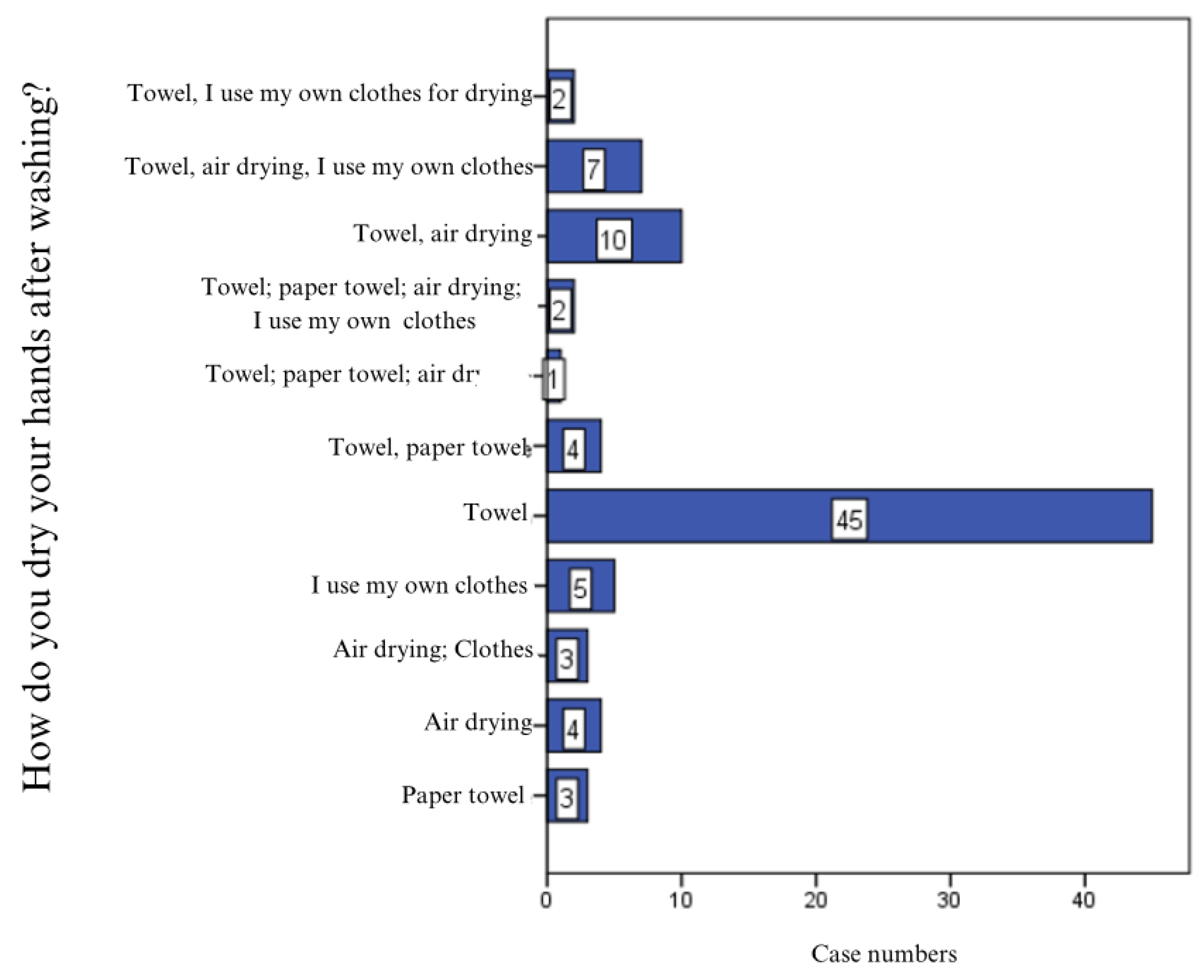

3.8. Hand Drying Method

Almost 50% of the respondents used paper towels for hand drying (45 cases) (p-value 0.581) as suggested in

Figure 9.

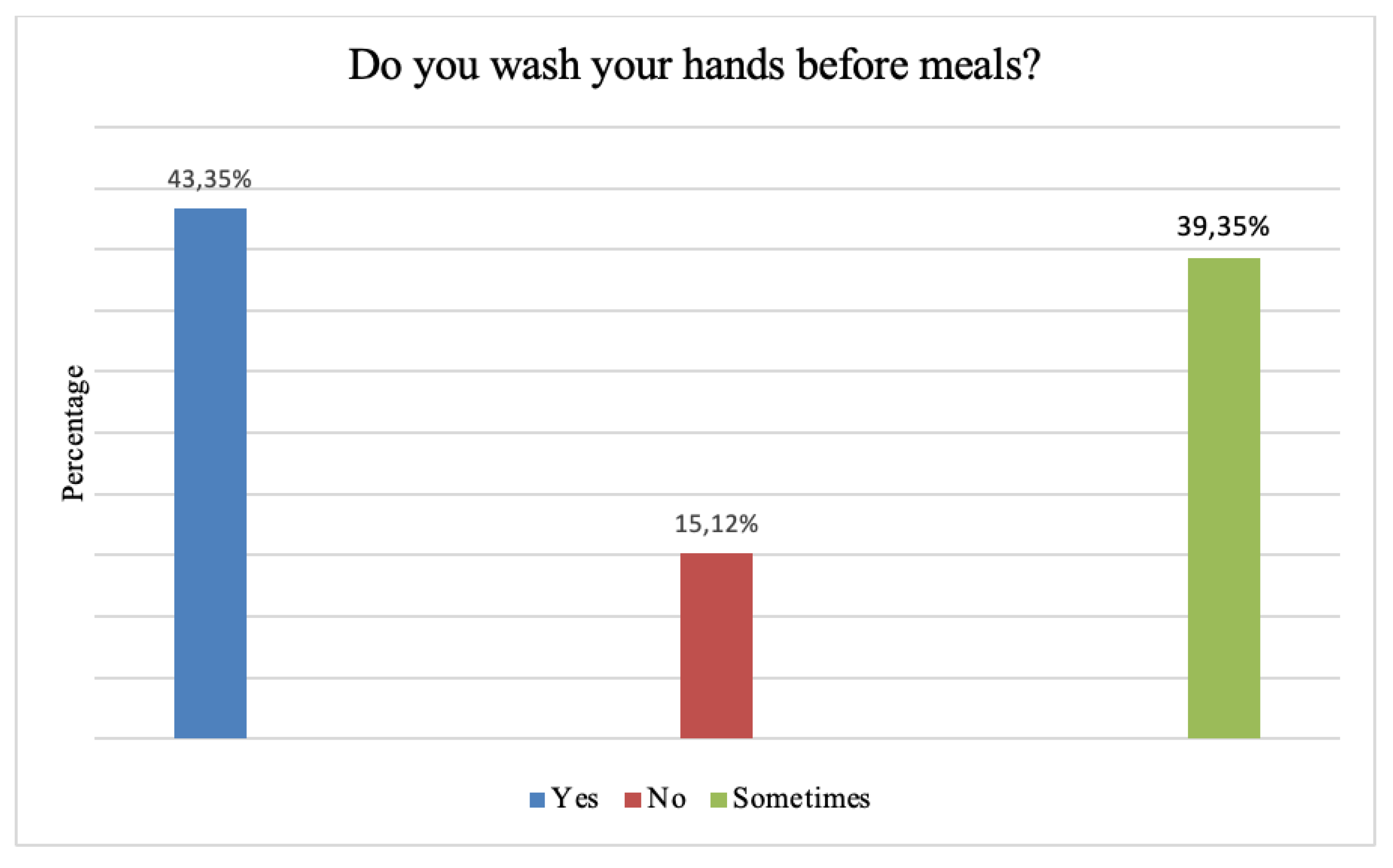

3.9. Hand Washing Before Meals

50% of participants answered wahing their hands before meals (43 answers) (p-value 0.009) as showed in

Figure 10.

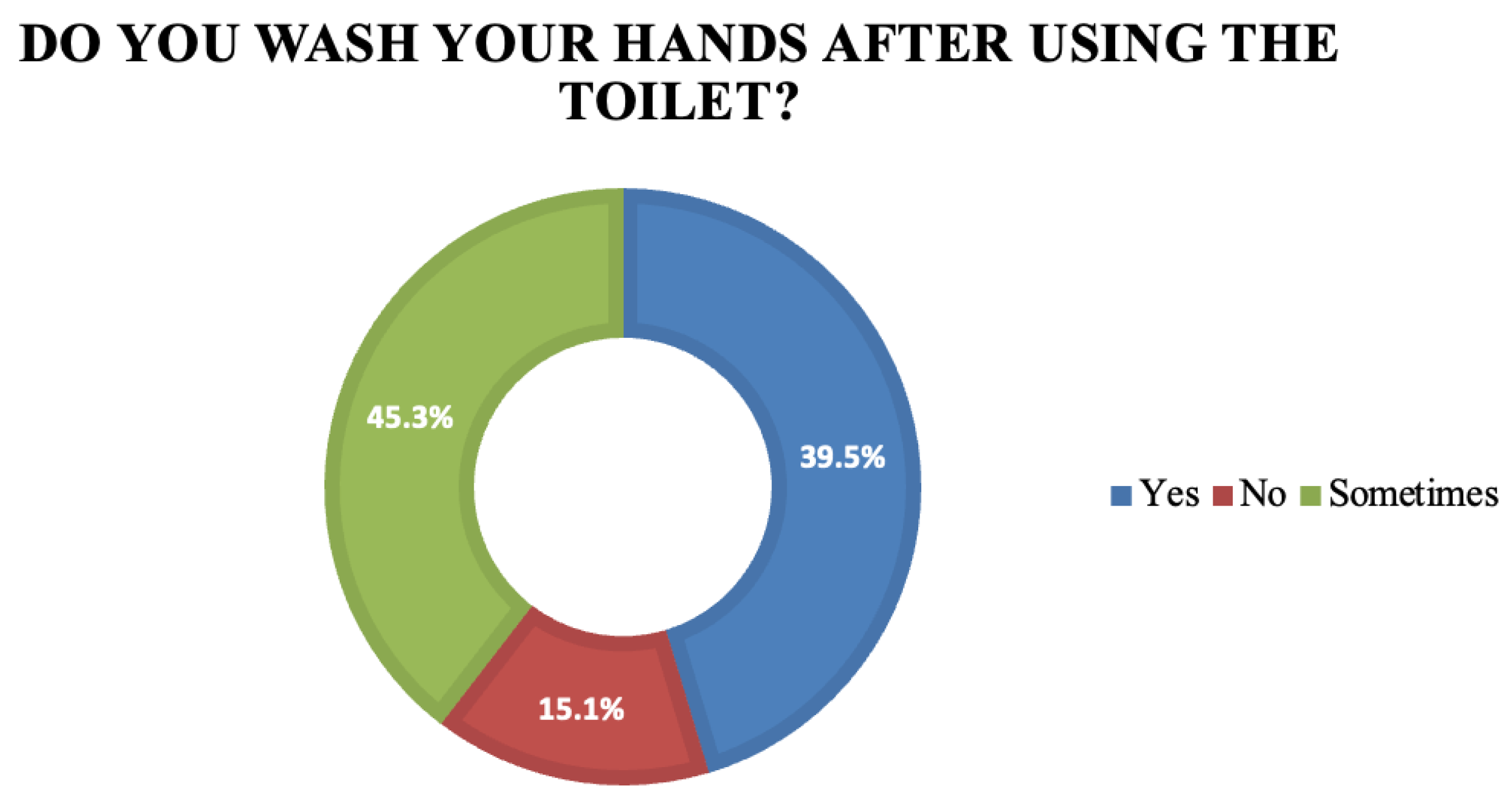

3.10. Hand Washing After Toilet Use

As

Figure 11 indicates, similar to the previous the previous point, the majority of participants expressed a positive answer (39 cases, 45.3%) (p-value 0.044) (

Figure 11).

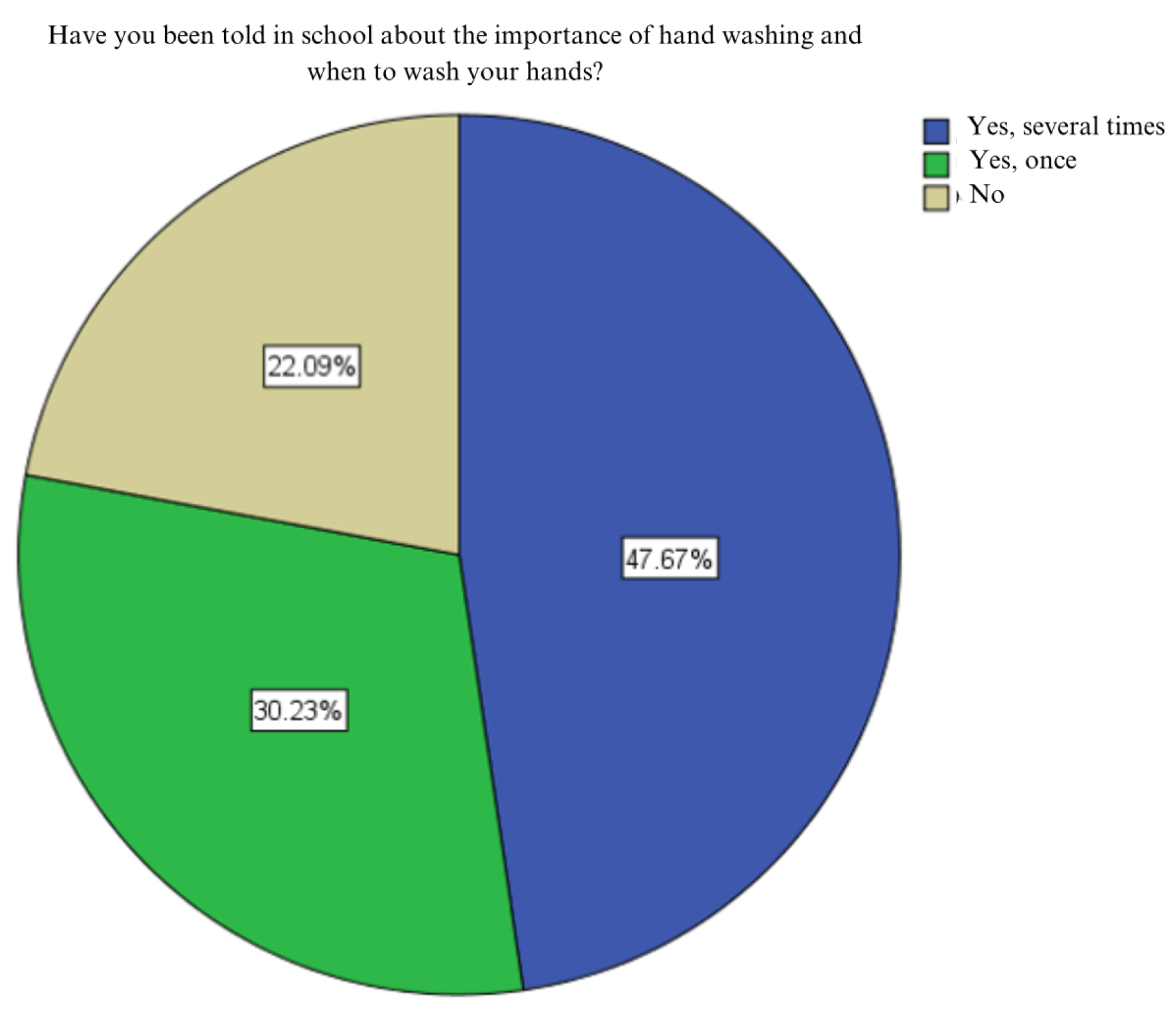

3.11. School Education on Hand Hygiene

Health education in school was assessed indirectly through this question, with the statistical analysis showing that 47.7% of participants (41 cases) frequently received information on this topic (p-value 0.068), as shown in

Figure 12.

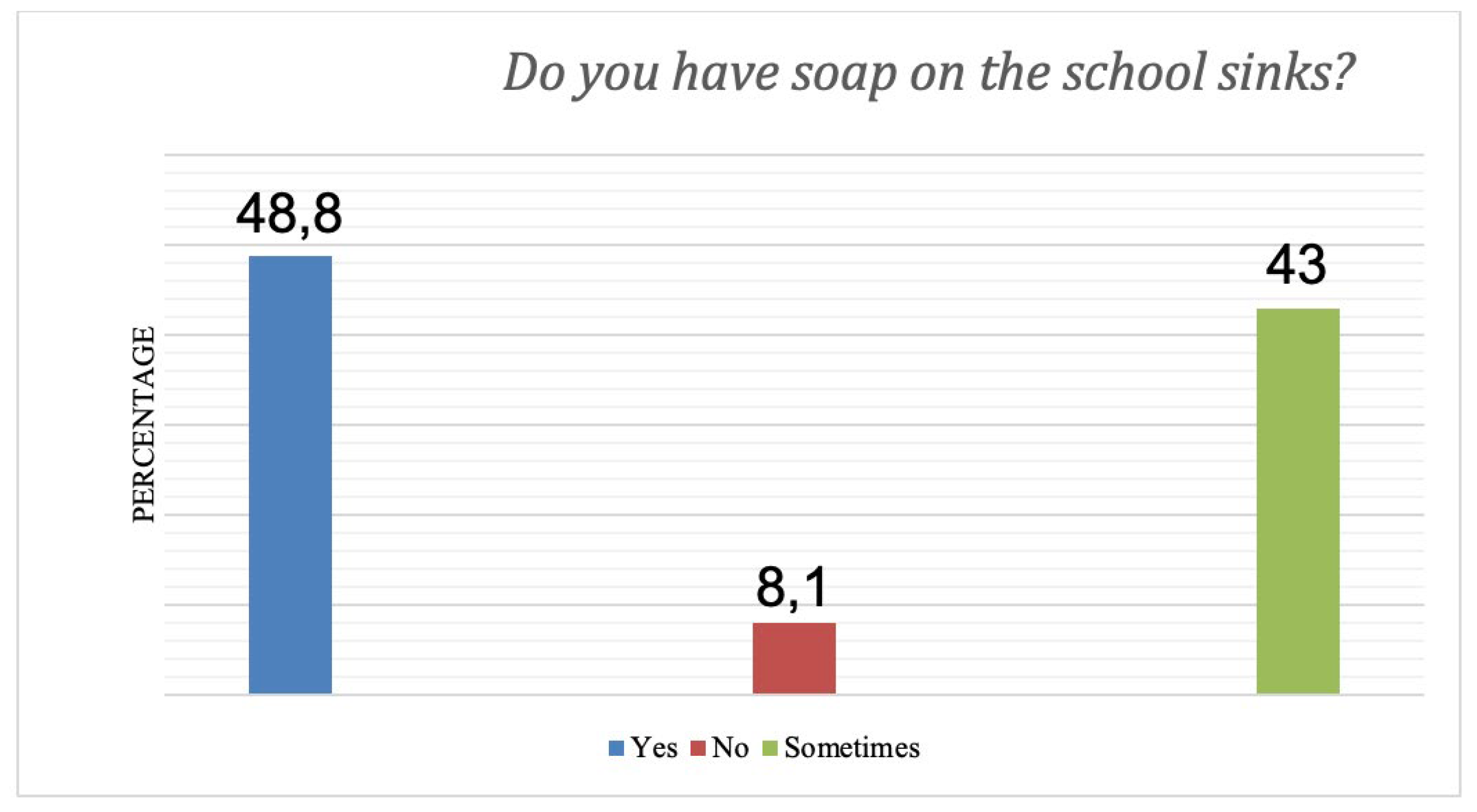

3.12. Soap Presence on the School Sink

Almost 50% of students reported the presence of soap in the school sink (42 cases, 48.8%) (p-value 0.031) as shown in

Figure 13.

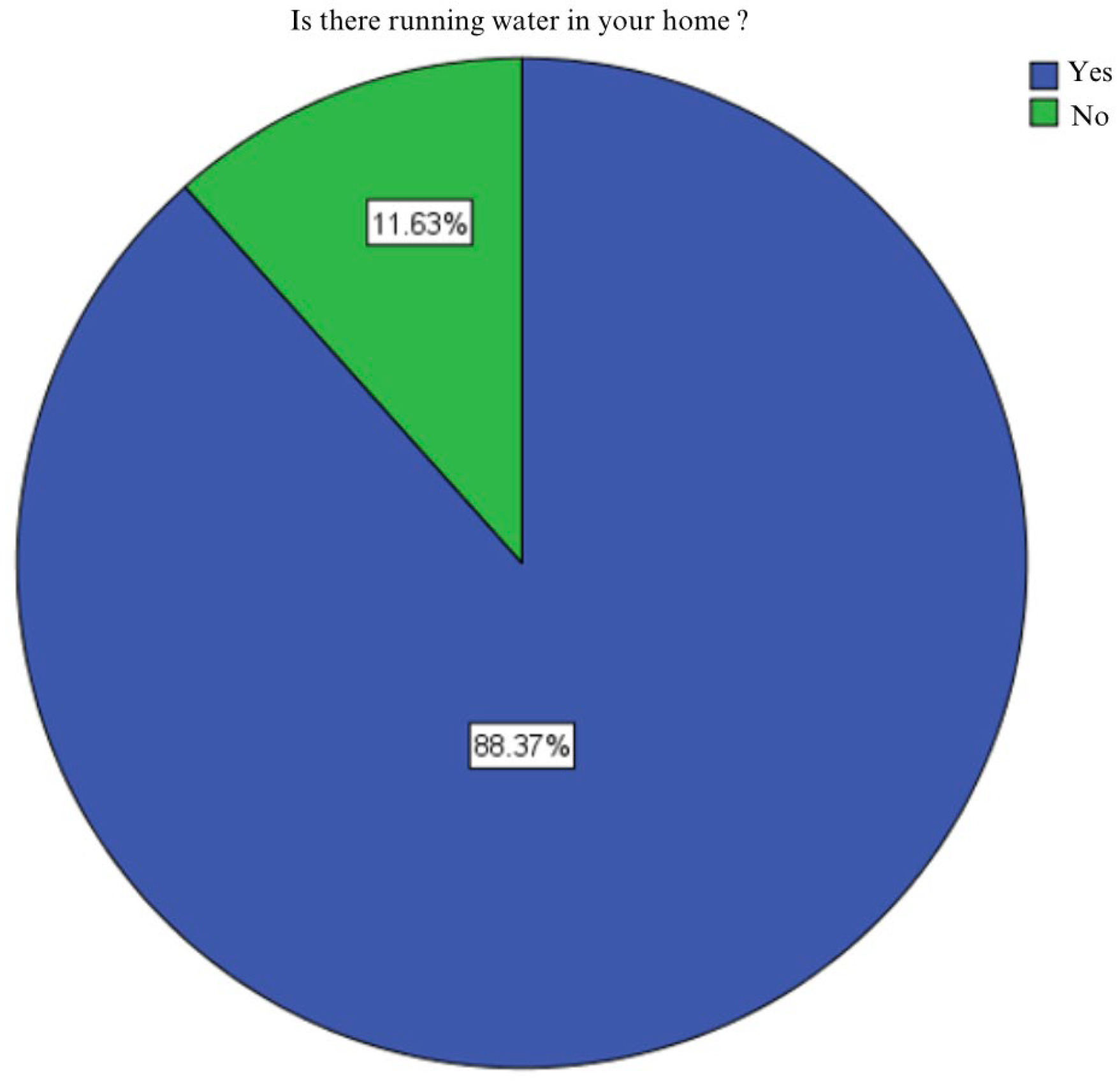

3.13. Presence of Running Water at Home

88.4% of respondents reported running water inside their home (76 cases) (p-value 0.018) as

Figure 14 shows.

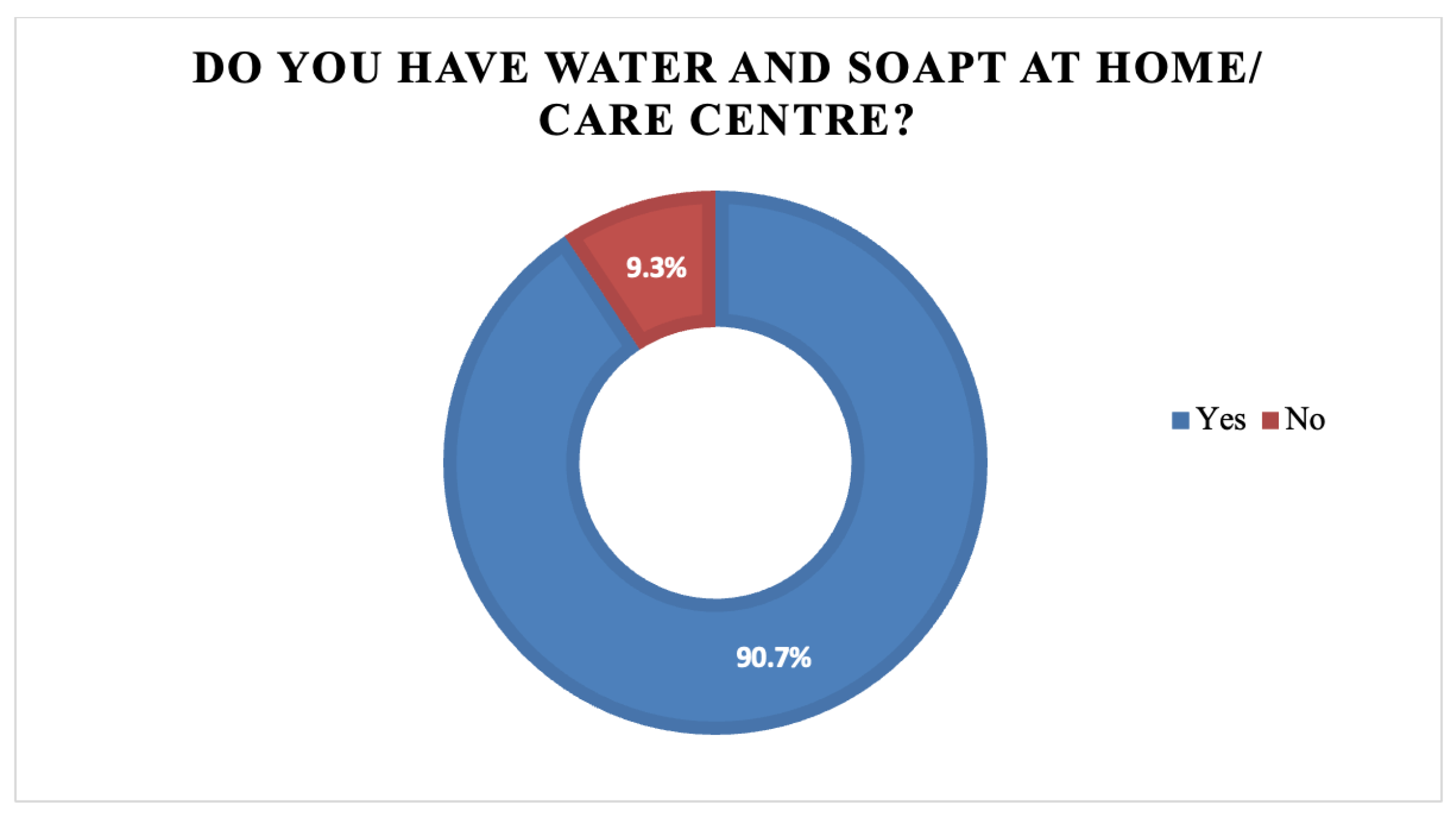

3.14. Water and Soap Presence at Home/Care-Centre

In 90.7% of cases, soap and water were available at home or care-centres (78 cases) (p-value 0.023) as

Figure 15 indicates.

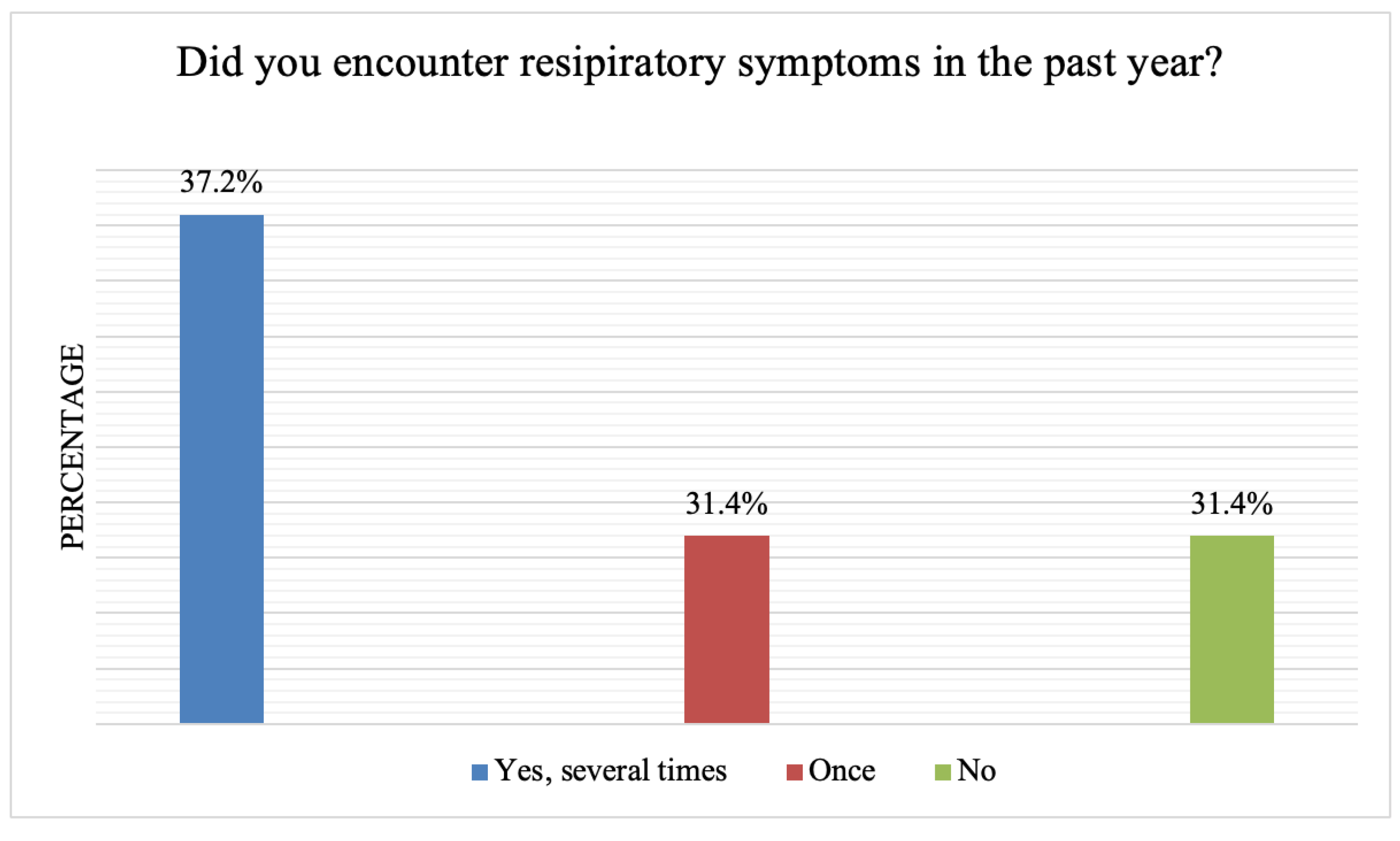

3.15. Presence of Resspiratory Symptoms in the Past Year

37.2% of patients had several episodes of fever over the course of a year (32 cases), followed by the same percentage who had symptims once or no symptoms (27 cases) (p-value 0.058) as shown in

Figure 16.

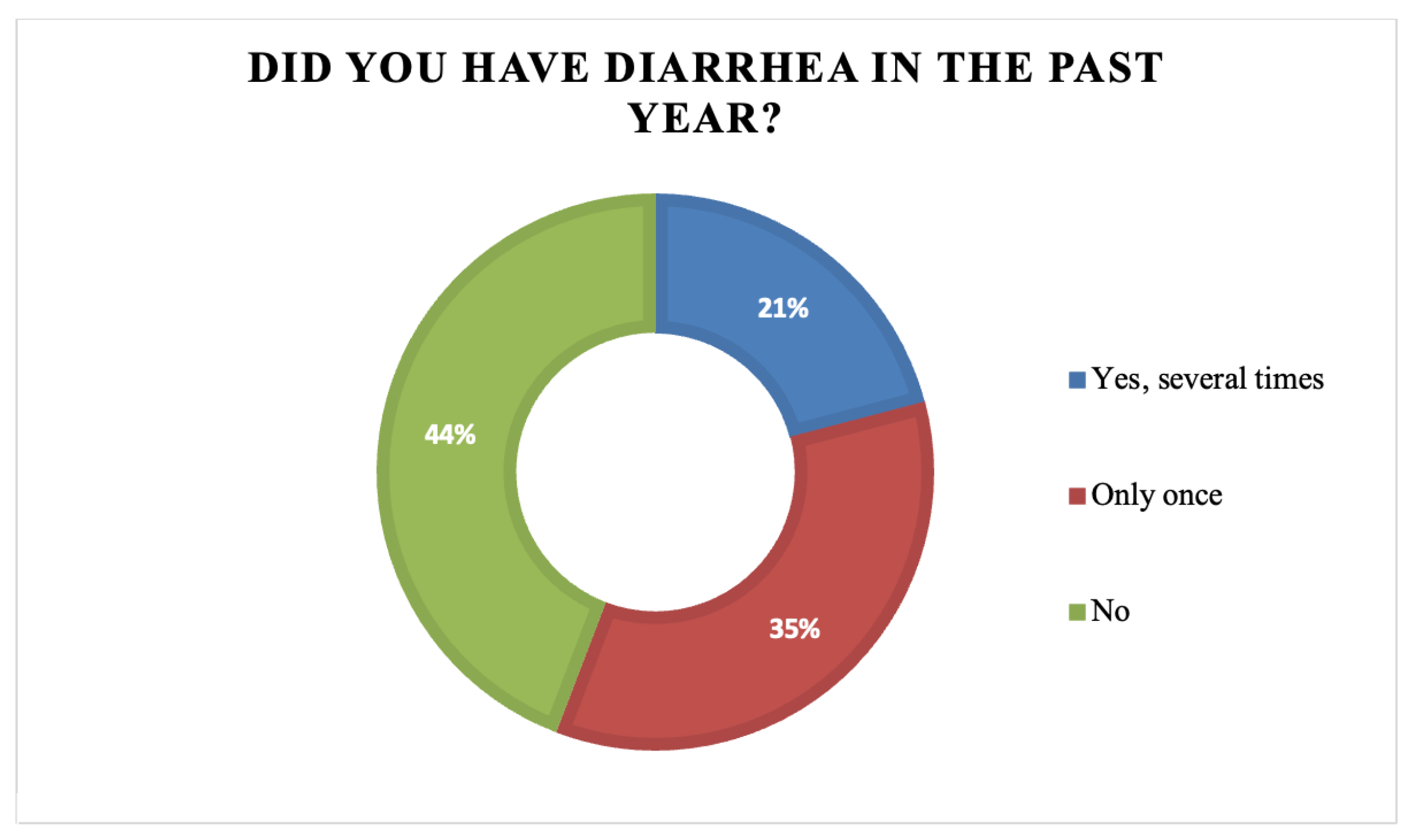

3.16. Presence of Diarrhea in the Past Year

44.2% of patients had no diarrhea in the last year (38 cases) (p-value 0.013) as

Figure 17 shows

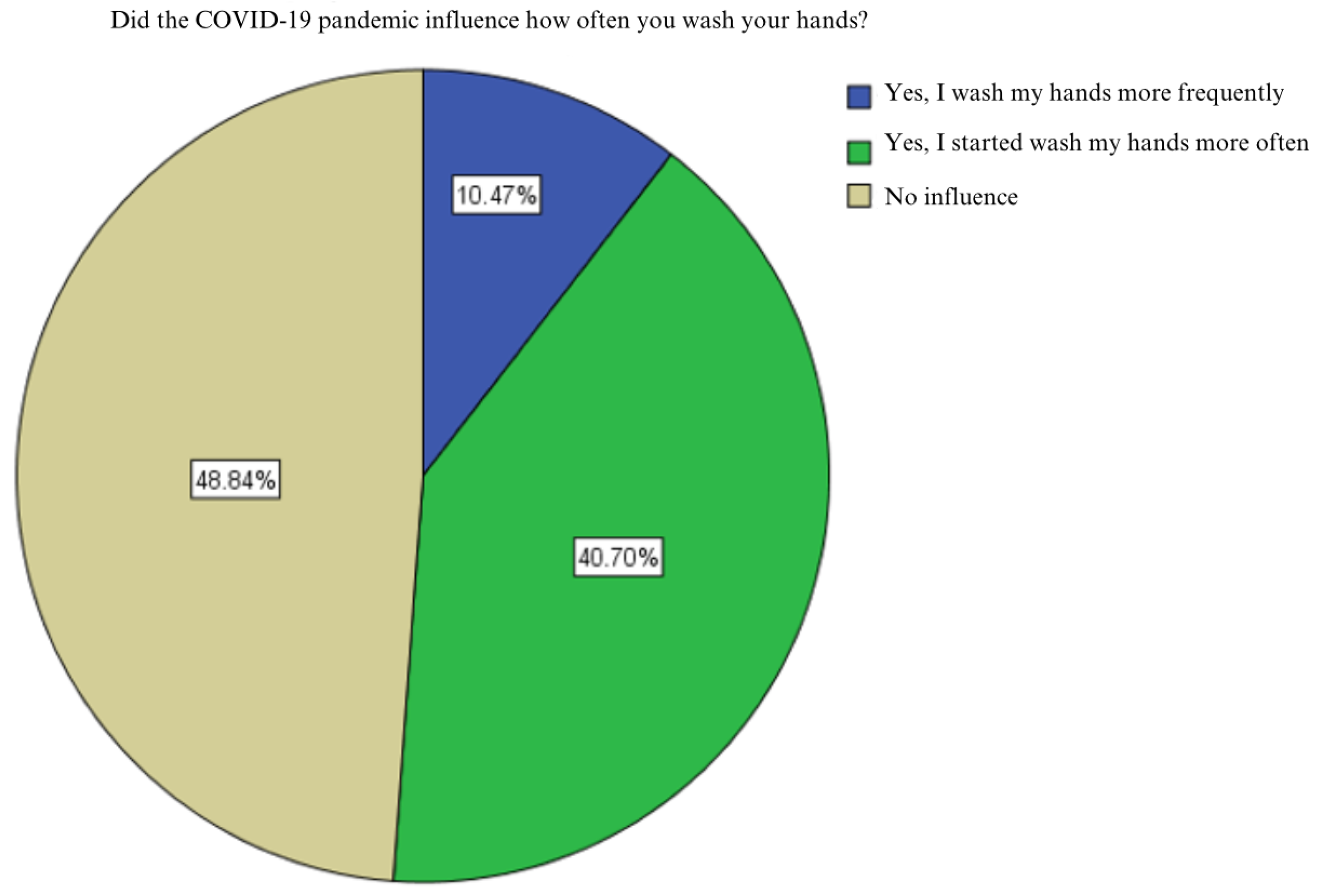

3.17. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Personal Hygiene

Regarding the impact of the pandemic on personal hygiene, 48.8% of subjects did not report a change in their hygiene habits (42 cases), followed by those who reported an improvement (35 cases, 40.7%) (p value 0.054) as shown in

Figure 18.

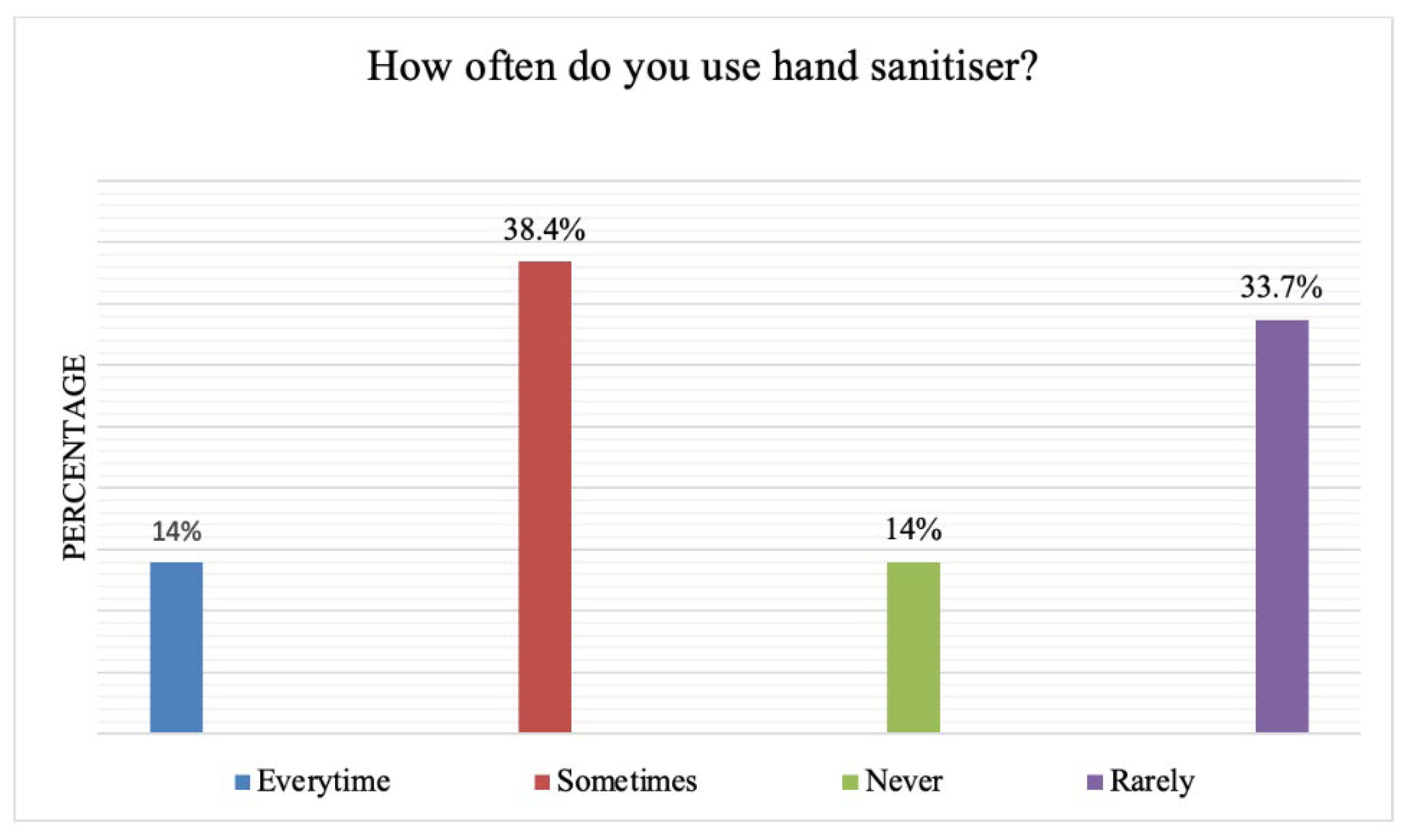

3.18. Hand Sanitiser Use

Hand snaitiser use was reported to be used occasionally by 38.4% of the participants (33 cases), while 33.7% reported infrequent use (29 cases) (p-value 0.038) (p-value 0.075) as

Figure 19 shows.

4. Discussions

Following the demographic data analysis of the 86 subjects, gender distribution was aproximately equal, females representing 52.3% of cases (53 girls) and males 47.7% (41 boys). The highest age incidence was between 10 and 13 years old (38 cases, 44.2% and the age between 6 and 9 years old (35 cases, 40.7%), followed by 13-16 years age group (14 cases, 15.1%).

As for the place of residence of the participants, 51.2% (44 cases) lived with the family, 46.5% (40 cases) lived with the family but also attended day-care centres. Two participants lived regularly at a foster care facility (2.3%).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has emphasized that consistent education and reminders about the importance of hand hygiene should be provided to adult healthcare workers. Children learn faster when observing adults [

14]. That’s why frequent hand washing is highly vital.

Approximately 80% of the children and adolescents (68 cases) included in this study were taught about proper hand hygiene by their parents/care-takers, while 19.9% were not instructed. This is an encouraging result as parent/guardian education plays an important role in ensuring that children develop good hand hygiene habits. Only 20% of subjects (18 cases) noticed their parents/care-takers washing their hands frequently, while 44.2% of participants noticed their parents or guardians washing their hands sometimes, 24.4% (21 cases) rarely noticed hand washing and 9 participants (10.5%) never noticed this habit.

Our subjects were interviewd regarding instructions given by adults working in the educational system. The majority of subjects contacted infiormation on hand hygiene (47.7%), while 22.1% did not receive any information.

A study conducted by Ruby Biezen, Danilla Grando and co., notived that the decision on hand hygiene is usually based on visible hand-dirt and parents are not informed on infection transmision and its consequences nor are the children. Implementing hand hygiene measures in the early stages of life will help the children to better respect these measures which could increase infectious diseases transmission [

15]. In this study, 44 of our participants (51.2%) declared washing their hands several times per day, those washing their hands when noticing visible hand dirt being represented by a percentage of 24.4% (21 cases), followed by 14 cases (16.3%) that was their hands as often as possible and 7 cases (8.1%) that wash their hands just once per day.

The World Health Organization recommends washing hands with soap and water for at least 60 seconds [

16]. However, 52 subjects wash their hands only for 10 seconds, followed by 28 cases 932.6%) that wash their hands between 20 and 30 seconds.

In addition, the study showed that 67.4% of respondents (58 cases) wash their hands only with water without soap. While water alone can kill some bacteria, soap is required to break them down and remove additional microorganisms from the skin. 30.2% of subjects (26 cases) use soap at every hand wash. This indicates a lack of awareness or non-compliance with the recommended duration of hand washing, which may impact the overall effectiveness of hand hygiene practices. Supplying schools with soap, hand sanitisers represent a real adavantage for children and their guardians [

17].

Hand drying technique represents another important aspect of hand hygiene. Bacteria and viruses can easily be transmitted through wet hands. Air drying is safer as using paper towels is linked with the increase of resistant bacteria and the proliferation of more virulent bacterial species [

6,

7].

Our study found that most of the participants use paper towels. To prevent the spread of infections after hand washing, appropriate hand disinfection techniques, such as removing paper towels and installing more air-drying devices could be implemented.

Washing hands before eating and after using the toilet is an essential practice to prevent the transmission of diseases. Encouragingly, 50% of participants reported washing their hands before eating and 45.3% reported washing their hands after using the toilet. However, these data highlight the need for ongoing education and awareness campaigns to promote consistent handwashing practices, particularly in key situations such as: before and during meals or after toilet use, animal interaction or touching the trash cans [

4]. Schools play an important role in teaching hand hygiene to children.

Additionally, the presence of soap in school sinks is important for students to learn to wash their hands properly. Almost 50% of respondents reported the presence of soap in school sinks, suggesting that school facilities need to be improved to ensure the availability of soap. Access to basic amenities such as running water and soap is essential for hand hygiene. Fortunately most participants (88.4%) had running water at home and 90.7% had access to soap and water at home and in public areas. This represent a good aspect since it shows that most details for effective hand hygiene are present.

This study also examined participants’ history of respiratory symptoms and fever. About 37.2% of the subjects had multiple symptoms during the year, highlighting the importance of hand hygiene in preventing the spread of respiratory diseases. Despite this, 44.2% of the study population did not suffer from diarrhea in the past year.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made many people aware of the importance of personal hygiene, including handwashing. In this study, 48.8% of respondents said that their hygiene habits did not change after the pandemic. Although this suggests that a significant percentage of participants maintained their hygiene practices, it is important to still emphasize the importance of regular handwashing, besides the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection to also prevent other infectious diseases.

Finally, using hand sanitizer represents another way to keep hands clean, especially when soap and water are not available. In this study, 38.4% of people reported using hand sanitizer occasionally. Although handwashing is a more convenient method, it is important to ensure that it is practiced correctly and properly in order to be effective.

Study Limitations

Despite the valuable information provided by this study, some limitations must be acknowledged. First, the sample size of the study was relatively small, which may limit the applicability of the results to a larger population of individuals. Secondly, the study relied on participants’ self-reported data, which may be subject to errors and inaccuracies. Additionally, the study focused on specific demographic groups and hand hygiene practices without considering other factors that could influence hand hygiene practices, such as cultural beliefs and socioeconomic factors. Future research to address the limitations provided in the composition of the most varied echantillon sizes, to use objective measures of compliance with the hygiene of the lines and to create a greater possibility of factors that can influence the hygiene practices of the hands.

5. Conclusions

Our study provides valuable information in regard to hand hygiene practices and awareness among children in a specific population. While there are positive aspects such as parental education and access to basic amenities such as running water and soap, there are also areas that require attention and improvement. The results underline the importance of targeted education and awareness campaigns to promote sustainable and appropriate use of hands.

In addition, efforts should be made to ensure the availability of soap in school buildings and to promote handwashing at appropriate times and in an appropriate manner. These improvements can lead to better hand hygiene practices among children, resulting in healthier communities.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was conduced in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance obtained from “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Center for Studies in Preventive Medicine, Timisoara, Romania, Institutional Review Board, research support officers. Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The research’s objectives, benefit and risks were explained to the participants before data collection and obtained written informed consent from the study participants. The research participants were assured of the attainment of confidentiality, and the information they give us will not be used for any purpose other than the research.

References

- Health topics-Hygiene. World health organizatiom. https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/hygiene.

- Journal of Dermatological Science. Sarah L, Wilson E, Nurinova NI. 2015, Vols. 80 (3-12).

- http://www.dspvs.ro/dsp2/images/GHID_OMS_IGIENA_MAINILOR_INSP.pdf.

- When and how to wash your hand. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/handwashing/when-how-handwashing.html.

- Effect of a behaviour-change intervention on handwashing with soap in India (SuperAmma): a cluster-randomised trial. Biran A, Schmidt W-P, Varadharajan KS, et al. 3, s.l. : The Lancet Global Health, 2014, Vol. 2. [CrossRef]

- The method used to dry washed hands affects the number and type of transient and residential bacteria remaining on the skin. Mutters R, Warnes SL. 4, s.l. : J Hosp Infect, 2018, Vol. 101. [CrossRef]

- Microbiological evaluation of different hand drying methods for removing bacteria from washed hands. Suen LKP, Lung VYT, Boost MV, et al. s.l. : Sci Rep, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Hygiene and health: systematic review of handwashing practices worldwide and update of health effects. Freeman MC, Stocks ME, Cumming O, et al. 8, 2014, Vol. 19. [CrossRef]

- A systematic review of hand-hygiene and environmental-disinfection interventions in settings with children. Leanne J. Staniford, Kelly A. Schmidtke. s.l. : BMC Public Health, 2020, Vol. 20. [CrossRef]

- Hygiene and sanitation: medical, social and psychological concerns. Geest, Sjaak van der. s.l. : CMAJ, 2015, Vol. 187. [CrossRef]

- Moffa M, Cronk R, Fejfar D, et al. A systematic scoping review of hygiene behaviors and environmental health conditions in institutional care settings for orphaned and abandoned children, Pag 1161-1174. Science of The Total Environment. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Effectiveness of a Hand Hygiene Program at Child Care Centers: A Cluster Randomized Trial. Martinez EA, Yui-Hifume R, Muñoz-Vico FJ,. s.l. : America Academy of Pediatrics, 2018, Vol. 142. [CrossRef]

- Hand Sanitiser Provision for Reducing Illness Absences in Primary School Children: A Cluster Randomised Trial. Priest P, McKenzie JE, Audas R, et al. s.l. : PLoS Med., 2014, Vol. 11. [CrossRef]

- CDC. Center of Disease Control and Prevention. Handwashing. Center of Disease Control and Prevention, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/handwashing/handwashing-family.html.

- Visibility and transmission: complexities around promoting hand hygiene in young children – a qualitative study. Biezen R, Grando D, Mazza D, et al. s.l. : BMC Public Health, 2019, Vol. 19. [CrossRef]

- Organization, World Health. Guide on Hand Hygiene in Outpatient and Home-based Care and Long-term Care Facilities. 2012.

- Effectiveness of a Behavior Change Intervention with Hand Sanitizer Use and Respiratory Hygiene in Reducing Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza among Schoolchildren in Bangladesh: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Biswas D, Ahmed M, Roguski K, et al. s.l. : Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2019, Vol. 101. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).