1. Introduction

Healthcare-associated infections are a major public health problem worldwide and are associated with increased hospital stay, long-term disability, increased resistance to antimicrobial drugs, poor clinical outcomes and unnecessary deaths [

1]. Healthcare-associated infections occur more frequently in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) due to a number of reasons that include insufficient resources, lack of training and inadequate support from microbiology laboratories [

2]. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, patients admitted to departmental wards have a 5% to 15% probability of acquiring a healthcare-associated infection during their stay [

2].

Healthcare workers’ hands are crucially important with respect to transmitting microorganisms responsible for healthcare-associated infections [

3]. In the last 20 years, evidence has accumulated to suggest that improved hand hygiene can reduce healthcare-associated infections [

3,

4]. Efforts worldwide to reduce the frequency and burden of these infections have therefore focused on hand hygiene, including the implementation of the World Health Organization (WHO)’s multimodal hand hygiene strategy [

5,

6].

Hand hygiene practices can be assessed using a WHO standard observation tool [

7], which outlines five opportunities of “moments” for observing hand hygiene within the health care setting. These include observing hand hygiene procedures (i) before a patient is touched, (ii) before clean or aseptic procedures are undertaken, (iii) after health care workers are exposed to bodily fluids, (iv) after a patient is touched, and (v) after health care workers touch a patient’s surroundings. This tool has been widely used in various African countries, finding on average poor levels of hand hygiene practices in various health care facilities [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

Sierra Leone has developed and launched a national strategic plan to combat antimicrobial resistance (2018–2022) as well as National IPC Guidelines (2022-2026) which clearly outline Infection Prevention Control (IPC) activities including hand hygiene practices that should be implemented in health care facilities throughout the country [

13]. Between June and August 2021, through an operational research project, hand hygiene practices were assessed using the WHO standard observational tool in two tertiary-level hospitals (34 Military Hospital -34MH- and Connaught Hospital) in Freetown, the capital city. [

14]. The findings from this study revealed less than 50% of hand hygiene opportunities were associated with compliance to accepted hand hygiene practices, with 34MH having a worse performance than Connaught Hospital. In both hospitals, compliance was also significantly worse before patient contact than after patient contact, in medical wards compared with paediatric wards and amongst doctors compared with nurses or nursing students [

14].

Various recommendations were made at the time in the published paper [

14], and in the plain language hand-out used to disseminate findings to various stakeholders [

15] to improve hand hygiene compliance. These recommendations included increasing awareness of the importance of hand hygiene in health facilities, training adapted to the local situation, posted reminders in wards and outpatient departments about good hand hygiene practices, a regular provision of alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) and other hand washing resources (such as soap items, water and veronica buckets) and strengthened monitoring and evaluation particularly if the facility fell below approved standards. These recommendations were supported by previous evidence from Rwanda, Ghana, Nigeria and neighbouring Guinea showing improved hand hygiene compliance after training and education, the placement of hand hygiene reminders in the health facility workplace and the provision of ABHR at points of care [

8,

9,

10,

11].

The current study was conducted to assess how the findings of the 2021 operational research were disseminated [

14], whether recommendations had been acted on and whether these translated into improvement in hand hygiene compliance. Glove use for healthcare workers was not measured in 2021. However, in the last two years the distribution of gloves improved throughout the country, mainly as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, and we decided to record glove use in 2023 as well as hand hygiene practices.

The aim of this study was to document and assess the dissemination and impact of hand hygiene compliance interventions recommended at two tertiary hospitals (34MH and Connaught Hospital) in Freetown, comparing the period June - August, 2021 with the period February - April, 2023. Specific objectives were to: i) describe dissemination activities resulting from the 2021 operational research findings, recommendations made and actions taken to promote hand hygiene compliance; ii) compare overall hand hygiene compliance between 2021 and 2023 in the two hospitals and in relation to the five opportunities for hand hygiene action, the different hospital wards and four different cadres of health care worker; and iii) assess and compare the use of gloves in the two hospitals between February - April, 2023.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

For objective 1, this was a descriptive study of dissemination, recommendations and action taken as a result of the first operational research study in 2021. For objective 2 and 3, this was a cross-sectional study using the standardised WHO observation tool to measure hand hygiene compliance [

7].

2.2. Setting

2.2.1. General Setting

Sierra Leone is a country on the west coast of West Africa, with a tropical climate and an environment that ranges from savanna to rainforests. The country has a total population of 7.5 million [

16]. There are five administrative regions, within which there are sixteen districts. Sierra Leone has a health care system consisting of primary, secondary and tertiary care facilities under the control of the Ministry of Health and Sanitation. Health services are mainly provided by the public sector, with some of the services offered by private sector providers, non-governmental and faith-based organisations and the military establishment.

2.2.2. Site-Specific Setting

The sites included in the study were 34MH and Connaught Hospital, both tertiary care hospitals situated in Freetown. 34MH has about 120 beds and serves military personnel and their dependents, as well as the civilian population. Every year 34MH admits about 2000 patients [

17]. Connaught Hospital has about 300 beds and caters largely for the civilian population. Every year, Connaught Hospital admits about 4900 patients [

18]. These two hospitals have been challenged in recent years with poor infrastructure and inadequate access to clean running water. Veronica buckets have been introduced to improve the water problem, although keeping these buckets filled up on a regular basis has not been easy. 34MH has also been undergoing extensive reconstruction in the last one year which has compromised hand washing facilities and infrastructure. The two hospitals and handwash infrastructure are shown in

Figure 1.

Each hospital has IPC focal persons trained by the National Infection Prevention and Control Unit (NIPCU). These focal persons identify IPC link personnel (who are mostly nurses) in each ward to support IPC practices. One of the important responsibilities of the IPC focal persons is to carry out quarterly audits of hand hygiene compliance among the different cadres of health care worker.

2.3. Study Population

The study population included healthcare workers at the two tertiary hospitals (34MH and Connaught), Freetown, Sierra Leone, where routine hand hygiene practices were observed by IPC link personnel between February and April 2023. Their hand hygiene practices were compared with those observed and reported in the same two hospitals between June and August 2021 [

14].

2.4. Study Procedures

2.4.1. Dissemination Activities

Dissemination tools that included a plain language handout [

15], a short (3-minute) and long (10-minute) power point presentation and an elevator pitch were developed during a Structured Operational Research Training Initiative (SORT IT) course module in May 2022: this module was held two months after publication of the paper [

19]. A stakeholder list was also developed that prioritised key policy and decision makers to whom dissemination should be done. Between May 2022 and January 2023 information was collected on the dissemination meetings held and the dates, the frequency of use of the dissemination tools and the number and cadre of key personnel who attended these meetings.

2.4.2. Recommendations, Decisions and Interventions

Recommendations and actions that were proposed in the published paper and hand-out were documented [

14,

15]. These included: i) trainings conducted for hospital staff and IPC personnel and the number of staff trained; ii) numbers of hand hygiene reminders and job aids on the tables and walls in the six departments of Medicine, Surgery, Paediatric, Intensive care, Accident & Emergency and Obstetrics/Gynaecology observed on a monthly basis between February and April 2023; iii) numbers of hand wash stations, running taps, Veronica buckets, receiving bowls, soap items, paper towels, and ABHR containers in the six general departmental wards observed on a monthly basis between February and April 2023; iv) information about ABHR monthly supplies and interruptions; and v) the supervisions, monitoring visits and hospital assessments conducted by NIPCU and hospital IPC from May 2022 onwards.

2.4.3. Hand Hygiene Compliance

In each hospital, the IPC link personnel observed hand hygiene compliance in the six designated hospital wards. The healthcare workers observed included doctors, nurses, nursing students and laboratory technicians as they went about performing routine patient care.

The same methodology as was used in the previous study for observing and recording hand hygiene compliance [

14] was used in this current study. In brief, before the data collection started in February 2023, a refresher training on how to use the WHO Hand Hygiene Observation Tool was conducted for the IPC link personnel who were to collect data during the observation sessions. Following the training, they used the WHO paper-based standard observation tool to measure hand hygiene compliance [

7].

During each observation session, which took on average 10–15 min, the IPC link person quietly recorded hand hygiene practices that included use of ABHR and hand washing without the health care worker being aware of this observation. This silent observation was to prevent or reduce bias such as the Hawthorne effect, where people change their behaviour because they know and are aware that they are being observed [

20]. The link nurses recorded their name and the ward on the back of the recording form so that they could be contacted if the data entries could not be read. In 2023, the IPC link personnel also recorded use of gloves, although comparisons with 2021 were not possible because use of gloves was not recorded at that time. The aim was to conduct between 300 and 400 observation sessions, approximately the same number as were conducted in 2021 [

14].

For each session, a record was made of i) the start and end time of the observation session; and ii) the department in which the observations took place. Each session had multiple opportunities, for which a record was made of i) the indication that motivated the hand hygiene action (before a patient was touched [bef-pat]; before performing a clean or aseptic procedure [bef-asept]; after exposure to body fluids [aft-b.f.]; after touching a patient [aft-pat]; and after touching the surroundings of a patient [aft.p.surr.]); and ii) the hand hygiene action – ABHR, handwashing with soap items and clean water or no hand hygiene action.

2.5. Data Variables and Sources of Data

Data variables were aligned to study objectives.

For Objective 1, these included: number and type of dissemination meetings; trainings conducted for hospital staff and numbers of IPC personnel and staff trained; in the six hospital departments observed on a monthly basis between February and April 2023, numbers of hand hygiene reminders and job aids on the tables and walls, hand wash stations, running taps, Veronica buckets, receiving bowls, soap items, paper towels, and ABHR containers and any interruptions to the ABHR supply; supervisions, monitoring visits and hospital assessments conducted from May 2022 These data were obtained from records, personal observations and routine monitoring visits.

For Objective 2 and 3, these included: hospital (34MH, Connaught); date of hand hygiene session; duration of session in minutes; use of handwash or ABHR; the five opportunities for hand hygiene action and hand hygiene actions, opportunities and hand hygiene actions in the six different hospital wards and amongst doctors, nurses, student nurses and laboratory technicians. We also recorded separately the number of times gloves were used during the observation period in 2023. The sources of data were the completed observation forms which were filled over a three-month period from February to April 2023.

2.6. Analysis and Statistics

We single-entered data in Excel and exported this to STATA (version 18, StataCorp. 2023. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.3.1) for analysis. Dissemination activities, recommendations and actions taken were described using frequencies and proportions. For hand hygiene variables, each moment or observation was the unit of analysis. Hand hygiene compliance was calculated as a percentage by dividing the number of handwash actions by the number of opportunities for hand washing. The compliance rate was compared between 2021 and 2023 for both hospitals and for the five opportunities for hand hygiene actions, for the six different hospital wards and the four different cadres of healthcare worker. Frequencies and proportions were also presented for the use of gloves in 2023. Comparisons were made between 2023 and 2021 using the chi-square test. Results were considered significant at the 5% level (p < 0.05, two-tail).

3. Results

3.1. Dissemination, Trainings, Recommendations and Actions Following the 2021 Study

Dissemination activities are shown in

Table 1. These largely consisted of a National SORT IT meeting and face-to-face/remote meetings with the hospital staff.

There were no funds for residential training of healthcare workers on hand hygiene compliance. However, there were “on the job” trainings: one full-day-training on hand hygiene compliance at Connaught Hospital on all the wards with 30 staff (general staff and IPC staff) and three half-day trainings on hand hygiene compliance at 34MH with a total of 100-150 staff trained.

Recommendations and actions taken to improve hand hygiene compliance are shown in

Table 2. Observations were made each month between February and April 2023, with the recommended actions being the same at each of these times. Connaught Hospital performed better than 34MH with more hand hygiene reminders/job aids and more infrastructure available for ABHR and hand washing. Within each hospital, the department of medicine performed best with the surgical department a close second.

Supervisions and IPC assessments of the two hospital using the adapted WHO Infection Prevention and Control Assessment tool (IPCAF) between April 2022 and May 2023 are shown in

Table 3. There were 11 such assessments conducted at Connaught Hospital and six at 34MH, with assessment grades being consistently ≥85%.

3.2. Comparison of Hand Hygiene Actions: Overall and Stratified by the Two Hospitals

There were 7206 opportunities for hand hygiene actions observed over 327 sessions in 2023 compared with 10,461 opportunities observed over 423 sessions in 2021. Of these 327 sessions in 2023, 202 (62%) took place in 34MH and 125 (38%) in Connaught Hospital compared with 84 (20%) in 34MH and 339 (80%) in Connaught Hospital in 2021.

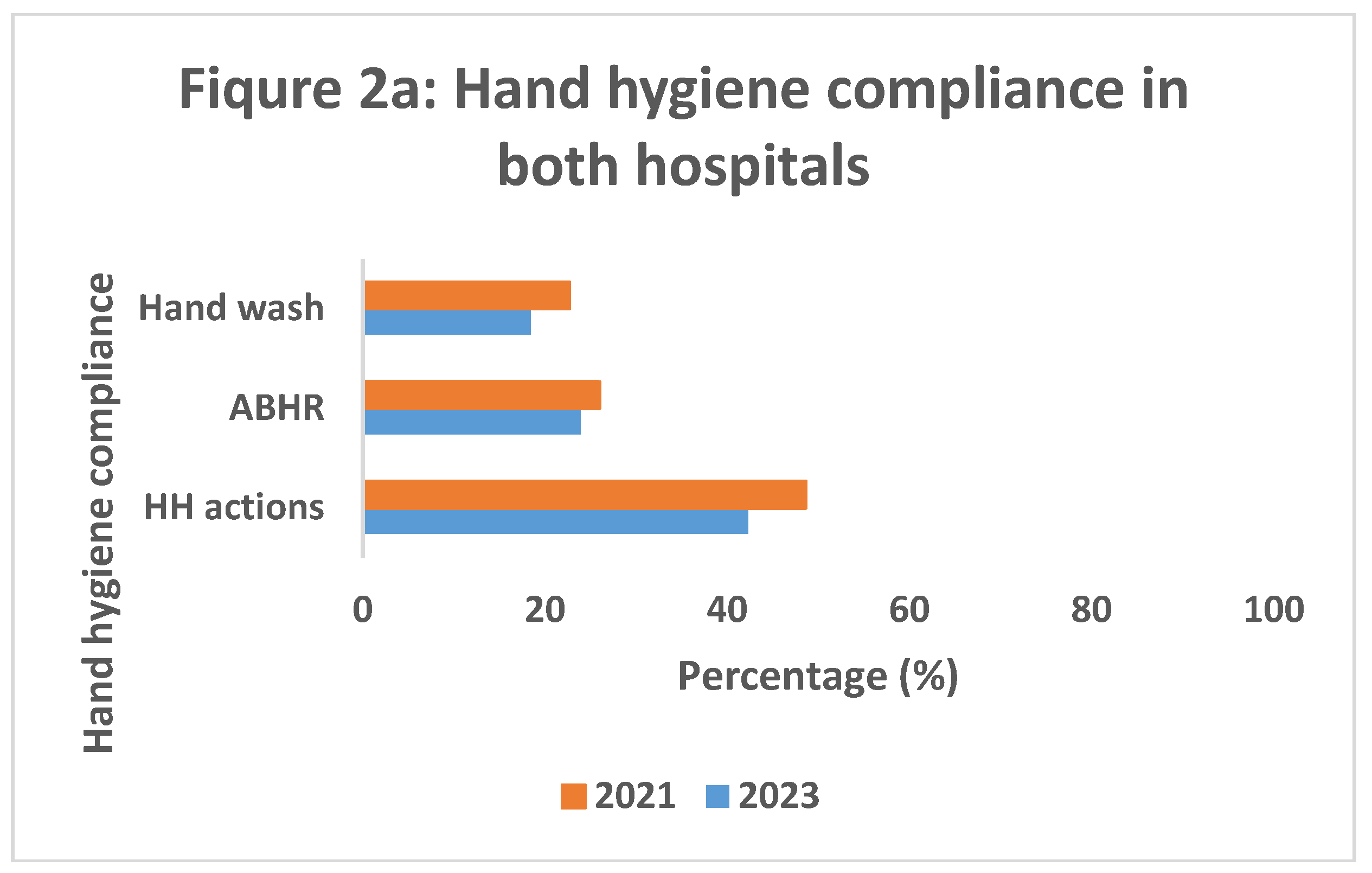

Hand hygiene compliance in the two hospitals overall, in 34MH and in Connaught hospital, is shown in

Figure 2. Overall (

Figure 2a), hand hygiene actions were performed in 3051 (42.3%, 95% confidence interval 41.2-43.5) of the 7206 opportunities in 2023, significantly lower than what was observed in 2021 when hand hygiene compliance was 48.6% (95% confidence intervals 47.7-49.6) –

P<0.001. This applied both to the use of ABHR (26% to 24%,

P<0.01) and hand wash (23% to 18%,

P<0.001).

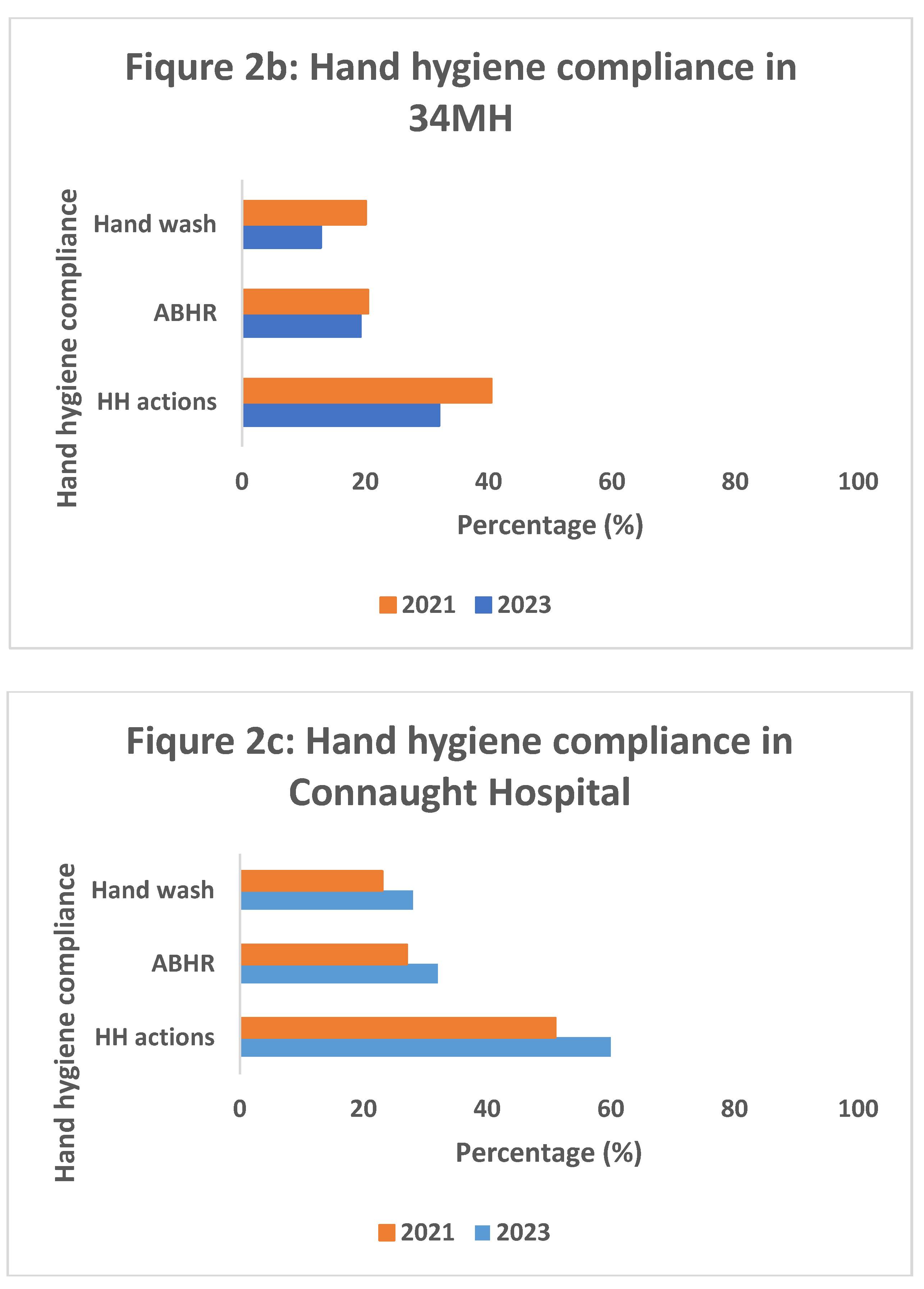

The two hospitals, however, differed in their performance. 34MH (

Figure 2b) showed a significant decline in hand hygiene compliance overall (40% to 32%, P<0.001), although this only applied to handwash (20% to 13%, P<0.001) and did not apply to ABHR (20% to 19%, P=0.24). Connaught Hospital (

Figure 2c) showed a significant improvement in hand hygiene compliance overall (51% to 60%, P<0.001), and for both ABHR (27% to 32%, P<0.001) and hand wash (23% to 28%, P<0.001).

Figure 2.

Comparison of hand hygiene compliance (and in relation to use of ABHR or hand wash) between June-August 2021 and February-April 2023 in two tertiary hospitals, Freetown, Sierra Leone: 2a = both hospitals together; 2b = 34 Military Hospital (34MH); and 2c = Connaught Hospital. ABHR = alcohol-based hand rub; HH = hand hygiene.

Figure 2.

Comparison of hand hygiene compliance (and in relation to use of ABHR or hand wash) between June-August 2021 and February-April 2023 in two tertiary hospitals, Freetown, Sierra Leone: 2a = both hospitals together; 2b = 34 Military Hospital (34MH); and 2c = Connaught Hospital. ABHR = alcohol-based hand rub; HH = hand hygiene.

3.3. Hand Hygiene Actions in Relation to Five Opportunities

Hand hygiene actions in relation to the five opportunities in each hospital are shown in

Table 4.

In both hospitals, and as observed in 2021, the lowest hand hygiene compliance overall was before touching a patient or before conducting a clean/aseptic procedure, while the best hand hygiene compliance overall was after the risk of body fluid exposure. The two hospitals, however, differed significantly in performance. Hand hygiene compliance was significantly worse for all five opportunities in 34MH. In Connaught Hospital hand hygiene compliance was significantly better before an aseptic procedure, after bodily fluid exposure and after touching a patient. There was no significant difference before touching a patient, but a significant decrease after touching a patient’s surroundings compared with 2021.

3.4. Hand Hygiene Actions in Relation to Hospital Departments/Wards

Hand hygiene actions in relation to hospital departments/wards in each hospital are shown in

Table 5.

In 34MH, hand hygiene compliance significantly decreased in all departments/wards between 2021 and 2023. In contrast, in Connaught Hospital hand hygiene compliance significantly increased in all departments/wards except for the Paediatric ward and Accident & Emergency in 2023 compared with 2021.

3.5. Hand Hygiene Actions in Relation to Type of Healthcare Worker

Hand hygiene actions in relation to type of health worker in each hospital are shown in

Table 6. In 34MH, there was a mixed picture when comparing 2023 with 2021, with hand hygiene compliance significantly improving in doctors but significantly decreasing in nurses and nursing assistants. In contrast, in Connaught Hospital there was a significant improvement in hand hygiene compliance in all health workers between 2021 and 2023.

Doctors particularly showed a significant improvement in hand hygiene compliance between 2021 and 2023 in both hospitals.

3.6. Use of Gloves in the Two Hospitals in 2023

Use of gloves in 34MH and Connaught hospitals during the observation period February to April 2023 are shown in

Table 7. During this time, gloves were observed to be used on 3156 occasions, 1842 in 34MH and 1314 in Connaught hospital. In both hospitals, gloves were predominately used before patient contact (95% of occasions in 34MH and 98% of occasions in Connaught hospital). In 34MH, gloves were used mainly in the Medical and Surgical departments as well as in Accident and Emergency while in Connaught Hospital they were mainly used in the Medical and Surgical departments. In both hospitals, nurses were the main users of gloves (nurses used gloves on 53% of occasions in 34MH and 45% of occasions in Connaught hospital). There was no data obtained on gloves during the observation sessions in 2021.

4. Discussion

This assessment of the impact of the 2021 operational research study on hand hygiene compliance in two tertiary hospitals in Freetown, Sierra Leone, yielded some interesting findings. Overall, hand hygiene compliance when added together in the two hospitals decreased in 2023, both with the use of ABHR and hand wash actions. There were, however, striking differences between the two hospitals. 34MH showed an overall decrease in hand hygiene compliance, mainly due to poor hand washing actions rather than poor use of ABHR, while Connaught Hospital showed an overall increase in compliance with both ABHR and hand washing. Why the differences between the two hospitals?

Dissemination activities, improved awareness and “on the job” trainings took place in each hospital, with more participation at 34MH compared with Connaught hospital. However, at the time of the study, 34MH was undergoing extensive reconstruction and this might have been responsible for the generally poor placement of hand hygiene reminders and job aids on the different hospital wards, the deficiencies in hand wash stations, the complete absence of running water or paper towels and interruptions of ABHR in the paediatric wards. In contrast, in Connaught Hospital there was much better placement of hand hygiene reminders and job aids, a four to eight times better distribution of hand wash stations and there was running tap water available on all wards. Supervision and IPC assessments were carried out twice as frequently at Connaught Hospital than at 34MH. Furthermore, IPC link personnel changed in 34MH during the two years, while in Connaught Hospital they mostly remained the same, there were at least two IPC focal points at Connaught Hospital compared with one at 34MH and there was a stronger hospital AMR committee established at Connaught hospital.

There is good evidence that WHO’s five-point multimodal strategy of system and improved infrastructure, education and training of healthcare workers, evaluation and feedback, health facility hand hygiene reminders and a climate of safety in health institutions can lead to a large, quick and sustained improvement in hand hygiene compliance in hospital settings [

21]. Solely addressing determinants such as improved knowledge, awareness and better supervision is not enough on its own to change hand hygiene behavior [

22]. Hand hygiene reminders and job aids, sufficient handwash stations and the uninterrupted presence of running water and soap are all significantly associated with improved hand hygiene in African hospital settings [

8,

23,

24,

25,

26]. These findings support our assumptions that workplace reminders and supportive hand hygiene infrastructure contributed to better practices at Connaught hospital. Paper towels are another well-established important contributor to hand hygiene [

27], and if these had been available in both the Freetown hospitals, this might have led to better hand hygiene compliance in both.

Similar to the 2021 study, we found that hand hygiene compliance was much better after contact or exposure to patients, their body fluids or their surroundings (self-protected opportunities) compared with before contact with a patient and before the performance of clean or aseptic procedures (patient protective opportunities). These findings are in line with previous reports from other African hospitals [

10,

11,

28,

29,

30,

31] and from two secondary hospitals in Sierra Leone [

32], where healthcare workers more readily performed hand hygiene actions to self-protect rather than for patient protection. In busy wards with high patient workloads, hand hygiene compliance decreases significantly [

33]. It may be that in these situations once healthcare workers have washed hands after touching a patient, they may feel it is unnecessary to repeat the procedure before seeing or touching the next patient. Another factor may be the use of gloves. We did not measure glove use in 2021. However, in 2023, gloves were used predominately before patient contact and especially in medical and surgical wards and by nurses more than any other type of healthcare worker. This may have led to a decrease in hand hygiene actions, especially before patient procedures. In Kenya, for example, the wearing of gloves often replaced hand hygiene actions, especially on surgical wards [

34].

Hand hygiene compliance deteriorated in all hospital departments and wards at 34MH, with compliance being uniformly between 30-33%, while at Connaught Hospital there was an overall improvement in all departments with compliance in medicine, surgery, paediatrics and intensive care being above 60%. The difference between the two hospitals very likely reflects the far better distribution of hand wash stations and hand wash infrastructure in the Connaught Hospital wards. While previous studies in African settings have shown little difference between departments and wards [

28,

30], a recent study in Eastern Ethiopia showed improvement in hand hygiene actions in medical and surgical wards over time [

35], findings that are in line with what we found at Connaught Hospital over the two-year period.

In both hospitals in Freetown, it was encouraging to see an improvement in hand hygiene compliance in doctors. Medical doctors are less likely to practice good hand hygiene compared with other cadres of staff [

36,

37], and previous studies in African settings have consistently shown hand hygiene compliance in doctors to be low and generally inferior to nurses and other health care worker cadres [

10,

28,

30,

38,

39]. The reasons for this improvement in doctors are unclear. They might have been related to the Covid-19 pandemic behavioral change or the involvement of medical doctors in the implementation of IPC programs in the hospitals might have been a contributing factor, all of these points deserving further investigation.

The strengths of this study were the documentation of dissemination activities and actions taken following the 2021 research study, the large number of hand hygiene opportunities that were observed in both studies, the use of the same WHO hand hygiene observation tool in the two studies and the conduct and reporting of the study according to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [

40].

However, there were a few limitations. Due to time constraints in 2023 we were not able to match the 10,000 hand hygiene opportunities that we observed in 2021, although we came close at just over 7000. In 2023, we also carried out more observations in 34MH and fewer in Connaught Hospital compared with 2021. This was because hand hygiene observations started first in 34MH, due to poor results in 2021, and funding provisions meant that the study had to stop in both hospitals at the same time. We recorded the use of gloves in 2023 which we did not do in 2021, so quantitative comparisons on the use of gloves in the two periods were not possible. As stated previously, hand hygiene compliance decreases with increasing patient workload [

33], and it would have been helpful to have measured this in the two hospitals and between the different hospital wards. Despite taking precautions in silent observation on hand hygiene practice, we cannot completely exclude the Hawthorne effect [

41]. Finally, we focused these two studies in 2021 and 2023 on two tertiary hospitals and our findings may not be generalizable to other facilities in Sierra Leone. A previous study in secondary hospitals in the country showed lower levels of hand hygiene compliance [

32].

In spite of these limitations, there are three important implications and recommendations that come out of this study. First, it seems clear from our findings in Connaught Hospital that multimodal interventions (especially hand hygiene reminders, good handwash infrastructure, education, training and supervision) are crucial for improving hand hygiene compliance on the ground. Sierra Leone is a local producer of ABHR, placing the country in a very good position to take this important intervention forward. In 2019, bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR) was estimated to have been directly responsible for 1.3 million deaths, with the highest concentration in West Africa [

42], and poor hand hygiene compliance is an important contributor to this. There is recent evidence to show that handwashing with soap significantly reduces the frequency of upper and lower respiratory tract infections [

43], another good reason to promote this simple behavior.

Second, despite Connaught Hospital having apparently sufficient handwash infrastructure, healthcare workers failed to practice hand hygiene actions in 40% of opportunities, so improvements are needed. We previously suggested new ways to improve hand hygiene actions such as use of “emojis” or “positive nudges”, interdepartmental competition, positive reinforcements and so on [

14]. In Nigeria, the installation of voice reminders in hospital wards significantly improved hand hygiene compliance [

44], and in Finland regular observations and feedback over a seven-year period in medical and surgical wards resulted in improved compliance amongst doctors and nurses [

45]. These innovations could be added to the list.

Third, while trying to improve hand hygiene practices in the two tertiary hospitals in the study, more needs to be done to expand the evidence base in Sierra Leone. Hand hygiene studies need to be conducted in other healthcare facilities throughout the country, and more qualitative research needs to be done to understand the enablers and barriers to better hand hygiene practice.

5. Conclusions

Following an operational research study in 2021 on hand hygiene compliance in two tertiary hospitals, Freetown, Sierra Leone, which led to recommendations and actions for improvement, a follow-up study on hand hygiene practices using the same methodology was conducted in 2023. Between the two years, hand hygiene compliance significantly improved in Connaught Hospital possibly as a result of better performance on hand hygiene reminders and hand wash infrastructure and more frequent supervisions. Hand hygiene performance on reminders, infrastructure and supervisions was inferior at 34MH and, combined with extensive reconstruction of the hospital at the time of the study, might have led to a general decrease in hand hygiene compliance in that hospital. Recommendations for further improvement of hand hygiene compliance in Sierra Leone include the addition of innovative ways to encourage health care workers to wash their hands and continued research to build the evidence base in healthcare facilities throughout the country and at different levels of the healthcare system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.M., D.K.,G.N.K., H.M.T., H.D.S., A.D.H.; methodology, M.M.M., D.K., G.N.K., S.S., Z.K., I.F.K., M.N.K., R.Z.K., S.S.T.K.K., S.A.K., S.M.; B.D.F., F.T., J.S.K., H.M.T., H.D.S., A.D.H.; validation, M.M.M., D.K., H.M.T., H.D.S., A.D.H.; formal analysis, M.M.M., D.K., H.M.T., H.D.S., A.D.H.; investigation, M.M.M.; resources, I.F.K.; data curation, M.M.M., H.M.T., H.D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.M., D.K., H.D.S., A.D.H.; writing—review and editing, M.M.M., D.K., G.N.K., S.S., Z.K., I.F.K., M.N.K., R.Z.K., S.S.T.K.K., S.A.K., S.M.; B.D.F., F.T., J.S.K., H.M.T., H.D.S., A.D.H.; visualization, M.M.M., D.K., H.M.T, H.D.S., A.D.H.; supervision, M.M.M.; project administration, M.M.M.; funding acquisition, I.F.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. We thank the IPC focal points and IPC link personnel for their dedication on observing hand hygiene opportunities and collecting data on hand hygiene actions.

Funding

The Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, represented by its department of health and social care (DHSC) has contributed designated funding for this SORT IT-AMR initiative, which is branded as the NIHR-TDR partnership, grant number AMR HQTDR 2220608. The APC was funded by DHSC. TDR is able to conduct its work thanks to the commitment and support from a variety of funders. A full list of TDR donors is available at:

https://tdr.who.int/about-us/our-donors .

Institutional Review Board Statement

For the previous hand hygiene operational research [

14], ethics approval was obtained from the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee (SLESRC) on 5 July 2021 and also from the Ethics Advisory Group, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France (21 June 2021, EAG number 09/21). For the current operational research, permission and ethics approval was obtained on 23 March 2023 for collecting data using an observational method from SLESCR. The study also received approval from the Union Ethics Advisory Group (EAG), The International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France (28 March 2023, EAG number 05/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

This study was a recognized component of infection prevention and control activities and as such, health care workers were observed silently for hand hygiene practices while they performed their routine duties. There was no recording of individual identifiable information. As such, written informed consent was deemed not to be necessary and the study was approved by the international and national ethics committees.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this paper (with gloves and without gloves) have been deposited at M9.figshare.23300417 (accessed 6 June 2023) and they are available under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership coordinated by TDR, the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organization. The specific SORT IT program that led to these study protocol included a partnership of TDR with the WHO country offices and ministries of health of Ghana, Nepal and Sierra Leone. It was implemented along with The Tuberculosis Research and Prevention Center Non-Governmental Organization, Armenia; The International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases, Paris, France and South East Asia offices, Delhi, India; Medecins Sans Frontières – Luxembourg, Luxembourg; ICMR–National Institute of Epidemiology, Chennai, India; Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium; Damien Foundation, Kathmandu, Nepal and Brussels, Belgium; CSIR water institute, Accra, Ghana; Kitampo Health Research Center, Accra, Ghana; Environmental Protection Agency, Accra, Ghana; The University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana, National Training and Research Centre in Rural Health, Maferinyah, Guinea.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Open access statement

In accordance with WHO’s open-access publication policy for all work funded by WHO or authored/co-authored by WHO staff members, WHO retains the copyright of this publication through a Creative Commons Attribution IGO license (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/legalcode) which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original work is properly cited.

Disclaimer

There should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of their affiliated institutions. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted.

References

- World Health Organizaton (WHO) Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-Associated Infection Worldwide; Geneva, Switzerland, 2011;

- Allegranzi, B.; Nejad, S.B.; Combescure, C.; Graafmans, W.; Attar, H.; Donaldson, L.; Pittet, D. Burden of Endemic Health-Care-Associated Infection in Developing Countries: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet 2011, 377, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegranzi, B.; Pittet, D. Role of Hand Hygiene in Healthcare-Associated Infection Prevention. J. Hosp. Infect. 2009, 73, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, L.; O’Connell, N.H.; Dunne, C.P. Hand Hygiene-Related Clinical Trials Reported since 2010: A Systematic Review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016, 92, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO) WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care; Geneva, Switzerland, 2009;

- Allegranzi, B.; Gayet-Ageron, A.; Damani, N.; Bengaly, L.; McLaws, M.L.; Moro, M.L.; Memish, Z.; Urroz, O.; Richet, H.; Storr, J.; et al. Global Implementation of WHO’s Multimodal Strategy for Improvement of Hand Hygiene: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organizaton (WHO) Hand Hygiene Technical Reference Manual; Geneva, Switzerland, 2009;

- Holmen, I.C.; Seneza, C.; Nyiranzayisaba, B.; Nyiringabo, V.; Bienfait, M.; Safdar, N. Improving Hand Hygiene Practices in a Rural Hospital in Sub-Saharan Africa. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016, 37, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labi, A.K.; Obeng-Nkrumah, N.; Nuertey, B.D.; Issahaku, S.; Ndiaye, N.F.; Baffoe, P.; Dancun, D.; Wobil, P.; Enweronu-Laryea, C. Hand Hygiene Practices and Perceptions among Healthcare Workers in Ghana: A WASH Intervention Study. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 13, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uneke, C.J.; Ndukwe, C.D.; Oyibo, P.G.; Nwakpu, K.O.; Nnabu, R.C.; Prasopa-Plaizier, N. Promotion of Hand Hygiene Strengthening Initiative in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital: Implication for Improved Patient Safety in Low-Income Health Facilities. Brazilian J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 18, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.A.; Diallo, A.O.K.; Wood, R.; Bayo, M.; Eckmanns, T.; Tounkara, O.; Arvand, M.; Diallo, M.; Borchert, M. Implementation of the WHO Hand Hygiene Strategy in Faranah Regional Hospital, Guinea. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenmayer, K.; Msamba, V.S.; Chilunda, F.; Kiologwe, J.C.; Seni, J. Impact of Hand Hygiene Intervention: A Comparative Study in Health Care Facilities in Dodoma Region, Tanzania Using WHO Methodology. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Sierra Leone National Strategic Plan for Combating Antimicrobial Resistance 2018–2022; Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2018;

- Kamara, G.N.; Sevalie, S.; Molleh, B.; Koroma, Z.; Kallon, C.; Maruta, A.; Kamara, I.F.; Kanu, J.S.; Campbell, J.S.O.; Shewade, H.D.; et al. Hand Hygiene Compliance at Two Tertiary Hospitals in Freetown, Sierra Leone, in 2021: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TDR AMR-SORT IT Evidence Summaries: Communicating Research Findings Available online: https://tdr.who.int/activities/sort-it-operational-research-and-training/communicating-research-findings (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Statistics Sierra Leone 2021 Mid Term Population and Housing Census. Provisional Results; Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2021;

- 34 Military Hospital Statistics. Annual Patient Admissions; Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2019;

- Lakoh, S.; Jiba, D.F.; Kanu, J.E.; Poveda, E.; Salgado-Barreira, A.; Sahr, F.; Sesay, M.; Deen, G.F.; Sesay, T.; Gashau, W.; et al. Causes of Hospitalization and Predictors of HIV-Associated Mortality at the Main Referral Hospital in Sierra Leone: A Prospective Study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TDR SORT IT - Operational Research and Training Available online: https://tdr.who.int/activities/sort-it-operational-research-and-training# (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Chen, L.F.; Vander Weg, M.W.; Hofmann, D.A.; Reisinger, H.S. The Hawthorne Effect in Infection Prevention and Epidemiology. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2015, 36, 1444–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luangasanatip, N.; Hongsuwan, M.; Limmathurotsakul, D.; Lubell, Y.; Lee, A.S.; Harbarth, S.; Day, N.P.J.; Graves, N.; Cooper, B.S. Comparative Efficacy of Interventions to Promote Hand Hygiene in Hospital: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2015, 351. [Google Scholar]

- Huis, A.; van Achterberg, T.; de Bruin, M.; Grol, R.; Schoonhoven, L.; Hulscher, M. A Systematic Review of Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategies: A Behavioural Approach. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuemu, V.; Ogboghodo, E.; Opene, R.; Oriarewo, P.; Onibere, O. Hand Hygiene Practices among Doctors in a Tertiary Health Facility in Southern Nigeria. J. Med. Trop. 2013, 15, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engdaw, G.T.; Gebrehiwot, M.; Andualem, Z. Hand Hygiene Compliance and Associated Factors among Health Care Providers in Central Gondar Zone Public Primary Hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alene, M.; Tamiru, D.; Bazie, G.W.; Mebratu, W.; Kebede, N. Hand Hygiene Compliance and Its Associated Factors among Health Care Providers in Primary Hospitals of Waghimira Zone, Northeast Ethiopia: A Mixed Study Design. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2022, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daba, C.; Atamo, A.; Debela, S.A.; Gebrehiwot, M. Observational Assessment of Hand Hygiene Compliance among Healthcare Workers in Public Hospitals of Northeastern Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soboksa, N.E.; Negassa, B.; Kanno, G.; Ashuro, Z.; Gudeta, D. Hand Hygiene Compliance and Associated Factors among Healthcare Workers in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Prev. Med. 2021, 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonnaya, G.U.; Ogbonnaya, U.L.; Nwamoh, U.N.; Nwokeukwu, H.I.; Odeyemi, K.A. Five Moments for Hand Hygiene: A Study of Compliance among Healthcare Workers in a Tertiary Hospital in South East Nigeria. Community Med. Public Heal. Care 2015, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyedibe, K.I.; Shehu, N.Y.; Pires, D.; Isa, S.E.; Okolo, M.O.; Gomerep, S.S.; Ibrahim, C.; Igbanugo, S.J.; Odesanya, R.U.; Olayinka, A.; et al. Assessment of Hand Hygiene Facilities and Staff Compliance in a Large Tertiary Health Care Facility in Northern Nigeria: A Cross Sectional Study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, G.; Gebrehiwot, M.; Girma, H.; Malede, A.; Bayu, K.; Adane, M. Application of the Gold Standard Direct Observation Tool to Estimate Hand Hygiene Compliance among Healthcare Providers in Dessie Referral Hospital, Northeast Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 32, 2533–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuosi, A.A.; Akoriyea, S.K.; Ntow-Kummi, G.; Akanuwe, J.; Abor, P.A.; Daniels, A.A.; Alhassan, R.K. Hand Hygiene Compliance among Healthcare Workers in Ghana’s Health Care Institutions: An Observational Study. J. Patient Saf. Risk Manag. 2020, 25, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoh, S.; Firima, E.; Williams, C.E.E.; Conteh, S.K.; Jalloh, M.B.; Sheku, M.G.; Adekanmbi, O.; Sevalie, S.; Kamara, S.A.; Kamara, M.A.S.; et al. An Intra-COVID-19 Assessment of Hand Hygiene Facility, Policy and Staff Compliance in Two Hospitals in Sierra Leone: Is There a Difference between Regional and Capital City Hospitals? Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, N.C.N.; Schweizer, M.L.; Reisinger, H.S.; Jones, M.; Chrischilles, E.; Chorazy, M.; Huskins, W.C.; Herwaldt, L. The Impact of Workload on Hand Hygiene Compliance: Is 100% Compliance Achievable? Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 1259–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibira, J.; Kihungi, L.; Ndinda, M.; Wesangula, E.; Mwangi, C.; Muthoni, F.; Augusto, O.; Owiso, G.; Ndegwa, L.; Luvsansharav, U.O.; et al. Improving Hand Hygiene Practices in Two Regional Hospitals in Kenya Using a Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) Approach. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, H.; Geremew, A.; Worku Kassie, T.; Dirirsa, G.; Bayu, K.; Mengistu, D.A.; Berhanu, A.; Mulat, S. Hand Hygiene Compliance and Associated Factor among Nurses Working in Public Hospitals of Hararghe Zones, Oromia Region, Eastern Ethiopia. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambe, K.A.; Lydon, S.; Madden, C.; Vellinga, A.; Hehir, A.; Walsh, M.; O’Connor, P. Hand Hygiene Compliance in the ICU: A Systematic Review. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 47, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Sendlhofer, G.; Gombotz, V.; Pregartner, G.; Zierler, R.; Schwarz, C.; Tax, C.; Brunner, G. Hand Hygiene Compliance in Intensive Care Units: An Observational Study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangura, I.A. The Impact of Multimodal Strategy Intervention Program on Hand Hygiene Compliance at a University Teaching Hospital in Sierra Leone (Ola During Children’s Hospital). Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, s498–s499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irek, E.O.; Aliyu, A.A.; Dahiru, T.; Obadare, T.O.; Aboderin, A.O. Healthcare-Associated Infections and Compliance of Hand Hygiene among Healthcare Workers in a Tertiary Health Facility, Southwest Nigeria. J. Infect. Prev. 2019, 20, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purssell, E.; Drey, N.; Chudleigh, J.; Creedon, S.; Gould, D.J. The Hawthorne Effect on Adherence to Hand Hygiene in Patient Care. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 106, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, I.; Bick, S.; Ayieko, P.; Dreibelbis, R.; Wolf, J.; Freeman, M.C.; Allen, E.; Brauer, M.; Cumming, O. Effectiveness of Handwashing with Soap for Preventing Acute Respiratory Infections in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet (London, England) 2023, 401, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, U.M.; Gajida, A.U.; Garba, R.M.; Gadanya, M.A.; Umar, A.A.; Jalo, R.I.; Adamu, A.L.; Ismai, F. ; Tsiga-Ahmed; Gwarzo, D.H.; et al. Effect of Voice Reminder on Compliance with Recommended Hand Hygiene Practise among Health-Care Workers in Kano Metropolis. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2021, 28, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojanperä, H.; Ohtonen, P.; Kanste, O.; Syrjälä, H. Impact of Direct Hand Hygiene Observations and Feedback on Hand Hygiene Compliance among Nurses and Doctors in Medical and Surgical Wards: An Eight-Year Observational Study. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 127, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Two tertiary hospitals and hand wash infrastructure, Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Figure 1.

Two tertiary hospitals and hand wash infrastructure, Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Table 1.

Dissemination activities following the operational research study on hand hygiene compliance which was conducted in two tertiary hospitals, Freetown, Sierra Leone, June and August 2021

Table 1.

Dissemination activities following the operational research study on hand hygiene compliance which was conducted in two tertiary hospitals, Freetown, Sierra Leone, June and August 2021

| Type of Dissemination |

Who Received

Dissemination |

Where Conducted |

Dissemination Tools Used |

When Conducted |

| Published Paper [14] |

1891 views

June 25, 2023 |

IJERPH |

Open Access |

Published March 2022 |

Hospital Meeting:

Face-to-Face |

50 people:

Department heads;

IPC focal point |

34MH

|

Power-point

Plain language hand-out |

May 2022 |

Hospital Meeting:

Face-to-Face

|

4 people:

IPC focal point

*IPC link personnel |

34MH

|

Plain language hand-out |

August 2022 |

| National SORT IT Dissemination Meeting: Face-to-Face |

50-100 people:

Medical superintendents; IPC focal points;

Senior management;

WHO;

UNICEF;

CDC;

Mission Hospitals |

Sierra Palms

Hotel, Freetown |

Published paper Power-point

Plain language hand-out |

November 2022 |

Hospital Meeting:

Face-to-face |

6 people:

IPC focal points

IPC link personnel |

Connaught

|

Plain language hand-out |

May 2022 |

Hospital Meeting:

Remote

|

3 people:

Hospital administrators |

Connaught

|

Published paper

Plain language handout

|

August 2022 |

Table 2.

Recommendations and actions taken to improve hand hygiene compliance between February and April 2023 in the departments and wards of the two tertiary hospitals, Freetown, Sierra Leone

Table 2.

Recommendations and actions taken to improve hand hygiene compliance between February and April 2023 in the departments and wards of the two tertiary hospitals, Freetown, Sierra Leone

| Recommendation |

Action |

Medicine |

Surgery |

Paediatrics |

Accident &

Emergency |

Intensive Care |

Obstetrics/

Gynaecology |

| |

| 34MH |

| |

| Place HH reminders/job aids in hospital departments |

No. HH reminders and job aids placed on walls or

Tables |

3 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

- |

2 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Improve hand wash infrastructure at hand wash stations |

No. Hand wash stations |

3 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

- |

2 |

| No. Running taps |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

2 |

| No. Veronica buckets |

3 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

- |

2 |

| No. Receiving bowls |

3 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

- |

2 |

| No. Soap items |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

- |

2 |

| No. Paper towels |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

0 |

| No. ABHR |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

- |

1 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Improve ABHR

Supplies |

ABHR supplied monthly |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

- |

Yes |

| ABHR missing monthly |

No |

No |

No |

No |

- |

No |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Connaught Hospital |

| |

| Place HH reminders/job aids in hospital departments |

No. HH reminders and job aids placed on walls or

Tables |

18 |

16 |

6 |

8 |

8 |

- |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Improve hand wash infrastructure at hand wash stations |

No. Hand wash stations |

16 |

16 |

6 |

8 |

6 |

- |

| No. Running taps |

8 |

8 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

- |

| No. Veronica buckets |

8 |

8 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

- |

| No. Receiving bowls |

8 |

8 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

- |

| No. Soap items |

16 |

16 |

4 |

6 |

6 |

- |

| No. Paper towels |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

| No. ABHR |

8 |

8 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

- |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Improve ABHR

Supplies |

ABHR supplied monthly |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

- |

| ABHR missing monthly |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

- |

Table 3.

Supervisions and Infection Prevention Control Assessments carried out at the two tertiary hospitals, Freetown, Sierra Leone between April 2022 and May 2023.

Table 3.

Supervisions and Infection Prevention Control Assessments carried out at the two tertiary hospitals, Freetown, Sierra Leone between April 2022 and May 2023.

| Hospital |

Type of Supervision |

Date of Supervision |

Grade Assessment of IPC at Each Supervision |

| 34MH |

NIPCU- IPC Assessment |

14-04-2022 |

87% |

| |

NIPCU-IPC Assessment |

14-04-2022 |

87% |

| |

NIPCU-IPC Assessment |

29-06-2022 |

90% |

| |

34MH- IPC |

29-08-2022 |

88% |

| |

NIPCU- IPC Assessment |

17-09-2022 |

87% |

| |

34MH- IPC |

28-02-2023 |

93% |

| |

|

|

|

| Connaught Hospital |

Connaught - IPC |

12-02-2022 |

93% |

| |

NIPCU- IPC Assessment |

24-03-2022 |

89% |

| |

Connaught - IPC |

3-04-2022 |

85% |

| |

NIPCU IPC Assessment |

5-05-2022 |

88% |

| |

Connaught - IPC |

2-08-2022 |

85% |

| |

NIPCU - IPC Assessment |

17-09-2022 |

89% |

| |

Connaught - IPC |

25-10-2022 |

83% |

| |

NIPCU - IPC Assessment |

30-11-2022 |

94% |

| |

Connaught - IPC |

25-02-2023 |

87% |

| |

NIPCU - IPC Assessment |

3-03-2023 |

85% |

| |

Connaught -IPC |

17-05-2023 |

89% |

Table 4.

Comparison of hand hygiene compliance, in relation to the five opportunities for a hand hygiene action, between June-August 2021 and February-April 2023 in two tertiary hospitals, Freetown, Sierra Leone

Table 5.

Comparison of hand hygiene compliance, in relation to hospital departments, between June-August 2021 and February-April 2023 in two tertiary hospitals in Freetown, Sierra Leone

Table 6.

Comparison of hand hygiene compliance, in relation to different health care worker cadres, between June-August 2021 and February-April 2023 in two tertiary hospitals in Freetown, Sierra Leone

Table 7.

Use of gloves in the two tertiary hospitals in Freetown, Sierra Leone, between February-April 2023.

Table 7.

Use of gloves in the two tertiary hospitals in Freetown, Sierra Leone, between February-April 2023.

| Procedures, Hospital Departments and Health Workers |

34MH

Use of Gloves |

Connaught Hospital

Use of Gloves |

| |

n |

(%) |

n |

(%) |

| Total use of gloves during the observation period |

1842 |

|

1314 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Medical ward |

382 |

(21) |

490 |

(37) |

| Surgical ward |

430 |

(23) |

526 |

(40) |

| Paediatric ward |

274 |

(15) |

50 |

(4) |

| Intensive care |

- |

- |

63 |

(5) |

| Accident & Emergency |

426 |

(23) |

185 |

(14) |

| Obstetrics/Gynaecology |

330 |

(18) |

- |

- |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Doctor |

375 |

(20) |

245 |

(19) |

| Nurse |

962 |

(53) |

590 |

(45) |

| Nursing student |

211 |

(11) |

226 |

(17) |

| Laboratory technician |

294 |

(16) |

253 |

(19) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).