1. Introduction

Two of the leading causes of death in children under the age of 5 years in South Africa remain diarrheal and respiratory infections [

1]. Although there are large bodies of evidence to suggest that hand washing with soap can reduce the infection rates of such illnesses, they are still a frequent occurrence and the burden of these diseases are felt within the child population [

2]. Contaminated hands play a major role in pathogenic transmission and it has been established that hands can carry different types of pathogenic material [

3]. Several observational studies have shown that children place objects or fingers in their mouths regularly, and hand samples have revealed both animal and human feacal matter on children’s hands, increasing their risk for diarrhoeal diseases [

4,

5,

6]. Studies have shown that there may be an increased bacterial load on the dominant hand as it is though that this hand is more likely to be used to pick up objects [

7]. According to reports higher standards of hygiene are normally found in girls especially in the under-5 age group [

8].

Hand washing interventions can reduce diarrheal diseases by as much as 30% [

9]. Studies indicate that hand washing with soap compliance (before the Covid 19 pandemic) was as low as 19% worldwide [

10] and that children’s hand hygiene (HH) compliance was around 42% [

11]. It can be expected that this figure will have improved during 2020-22 as there is research to suggest that fear during pandemics increases compliance of HH practices [

12], although recent studies have shown that compliance wanes over time regardless of external factors, such as pandemics [

13,

14].Hand hygiene interventions are well documented and range from providing water, sanitation and hygiene [

15] to providing education on hand hygiene with practical demonstrations on how to wash hand [

16,

17,

18]. Proper hand hygiene could prevent hygiene-related diseases in preschool children and therefore, ensuring proper and effective hand washing amongst preschoolers could assist in preventing or reducing the occurrence of these diseases.

This paper will investigate whether a simple hand hygiene intervention administered to preschool children aged 4-5 years could reduce microbiological counts on their hands. The objectives were to compare the microbial counts of left and right hands; differences between the microbial counts on boys’ and girls’ hands and the difference in microbial counts between the intervention group (IG), who were administered the hand hygiene intervention and the control group (CG), who were not.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was a pre- and post-test conducted at preschools located in the Kempton Park suburbs of the city of Ekurhuleni, South Africa [

19]. Considering the resources available, a random sampling approach was used and targeted children attending preschool between the age group of 4 and 5 years. The legal parent, guardian and relevant authority were provided with information pertaining to the study and provided their written informed consent to allow their children participate in this study. Children gave informed assent making use of a pictoral representation of the sample process and affixing a sticker to the assent form if they agreed to participate. The study design was approved by the University of Johannesburg’s Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (REC -01-165-2017) and the Ministerial Consent for Non-Therapeutic Research on Minors for Department of Health National Ethics Research Council (GP-201804-002) and was conducted in compliance with procedures approved under a published study protocol [

20].

2.2. Sample Collection

A controlled intervention study was conducted at randomly selected preschools in Ekurhuleni, Gauteng (N=17) from February to December 2019. The schools were randomly placed into intervention (n=9) and control (n=10) groups with 160 children (N=160) participating pre-intervention (IG n=81 and CG n=79) and 148 children (N=148) participating post-intervention (IG n=77 and CG n=71). In the pre-intervention study, right- and left- hand bag-wash samples were collected from the participating children separately in sterile polyethylene Ziploc bags containing 70ml sterile phosphate buffered saline solution (Sigma Life Sciences; pH 7.02). The children’s hands were sampled immediately from their current activity and each child was required to rinse each hand in the bag for approximately 20 sec. A note was made on the gender of each child according to their sex assigned at birth, as the sample was collected. The post-intervention sampling occurred two months after the pre-intervention samples were collected. Bag-wash samples were collected from the participating children immediately on arrival at the preschool, with the children being required to wash both their hands, by interlocking digits for approximately 20 sec, in a single sterile polyethylene Ziploc bag containing 100ml sterile phosphate buffered saline solution (Sigma Life Sciences; pH 7.02). These samples were labelled as “before” samples. The children were then instructed to “wash” their hands as they normally would and return for an “after” sample. The “after” bag-wash sample was collected in the same way as the “before” sample in a separate bag. Notes were made as to whether children used soap or not when washing their hands prior to the after bag-wash sample being collected.

2.3. Sample Analysis

Quantitative analysis was applied to pre-intervention (right and left) bag-wash samples testing for viable (intact) and total bacterial cell populations using flow cytometry (FCM). The samples were analysed separately (70ml quantity) and were then combined (100ml quantity adjusted) so that the combined (100ml) results could be compared to the post-intervention samples in a like-for-like quantity (100ml).

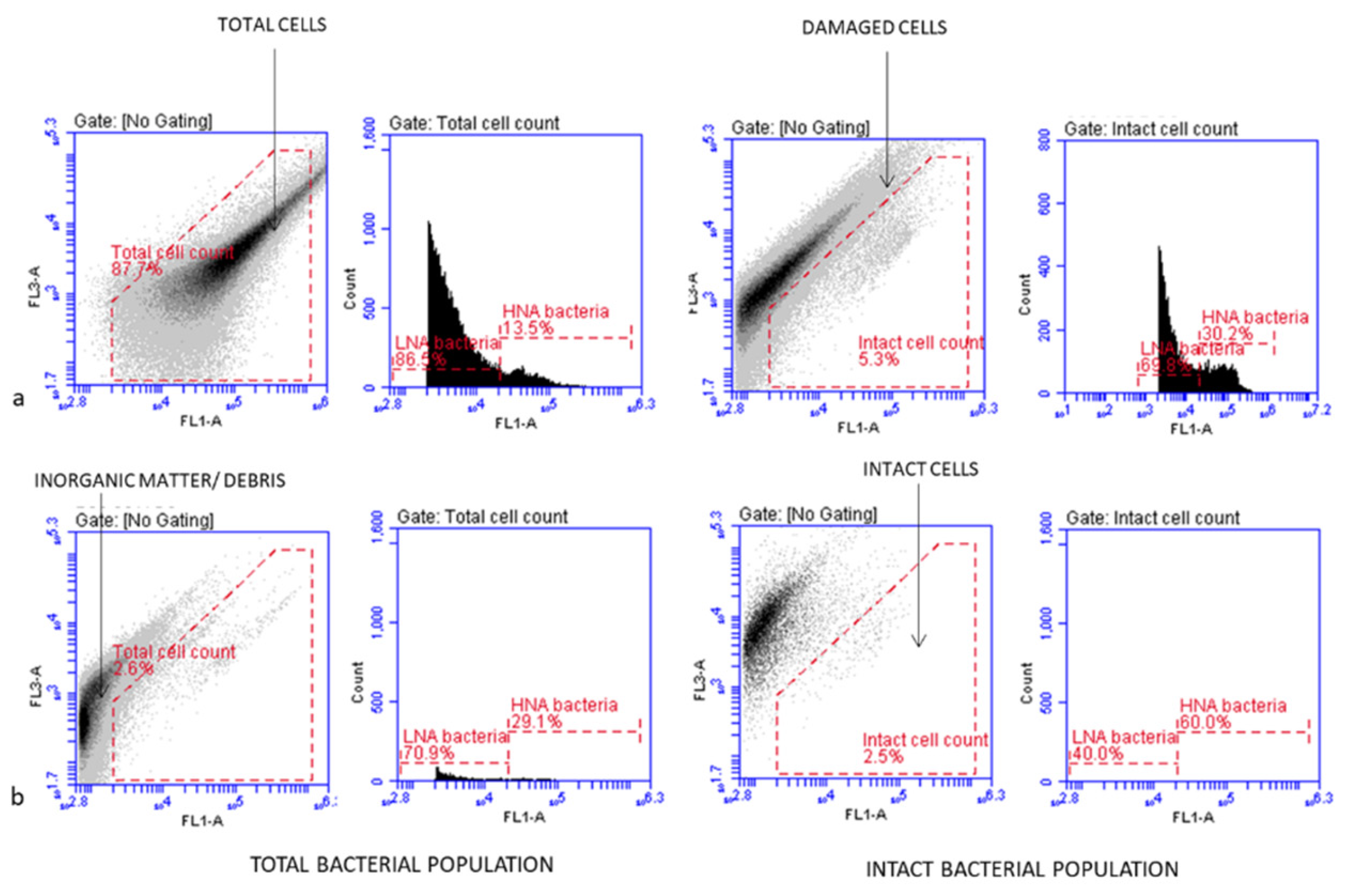

Flow cytometric (FCM) analysis was performed on the BD Accuri C6 with CSampler according to Singh et al. 2019. Briefly, 500ul bag wash samples were stained at 37°C for 10 minutes with SYBR Green I (Invitrogen) at a concentration of 1X for total bacterial cell counts and SYBR Green I (Invitrogen) at a concentration of 1 X was co-stained with 6 μM Propidium Iodide (PI) (BD Biosciences) for intact bacterial cell counts. The stained samples were then measured separately at medium speed using an FL1-H acquisition threshold of 800. The Eawag bacterial cell analysis template was used to detect and the bacterial cell populations by electronic gating, and manual compensation was used where necessary to separate positive signals from debris as indicated in

Figure 1 [

21]. Flow cytometry targeted all bacteria present on the children’s hands and was able to indicate more than one group of bacteria. It compensates for the viable but non-culturable bacteria that would have skewed any culture-based data.

Post-intervention data per set of 100ml bag-wash samples was analyzed for turbidity, and viable (intact) and total bacterial cell populations.

The turbidity was measured in nephelometric turbidity units (NTU). Turbidity of hand wash samples was determined using the TN-100 Turbidimeter (Eutech, Singapore). Before sample readings the turbidimeter instrument was calibrated as recommended by the manufacturer and the South African Water Quality guideline standards. The primary standards included: 0.02, 20.0, 100, 800 Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU) provided along with the meter. The sample vessel was rinsed three times with at least 10ml of the sample after which the sample was added to the vessel up to the mark indicated on the vessel. The reading was read with the turbidimeter and used as read. Any differences in the turbidity pre- and post- hand washing was recorded along with log10 reductions on both live (intact) cells and total bacterial count.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data was captured on an Excel spreadsheet and uploaded to IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 for statistical analysis. All FCM data was processed with the BD Accuri C6 software, and boxplots were computed with GraphPad Prism 8 software. Pre-intervention, a non-parametric test was conducted (Mann-Whitney U test) to determine differences between the results of right and left hands and Spearman’s rho non-parametric correlation coefficient was used to assess the relationship between total bacterial count and the intact live cells count on both the right and left hands. The same tests were conducted on results for gender differences. Post-intervention a Spearman correlation was run to determine the relationship between the total cell count and intact live cells before and after children had washed their hands with or without using soap. A data set was created for the results of all children whose hands were sampled prior to the intervention and post-intervention (N=148) in both IG and CG so that pre-intervention results could accurately be compared to post-intervention results. A Friedman test was conducted in order to measure the three points in time to obtain a mean rank and a Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to indicate significant differences between these.

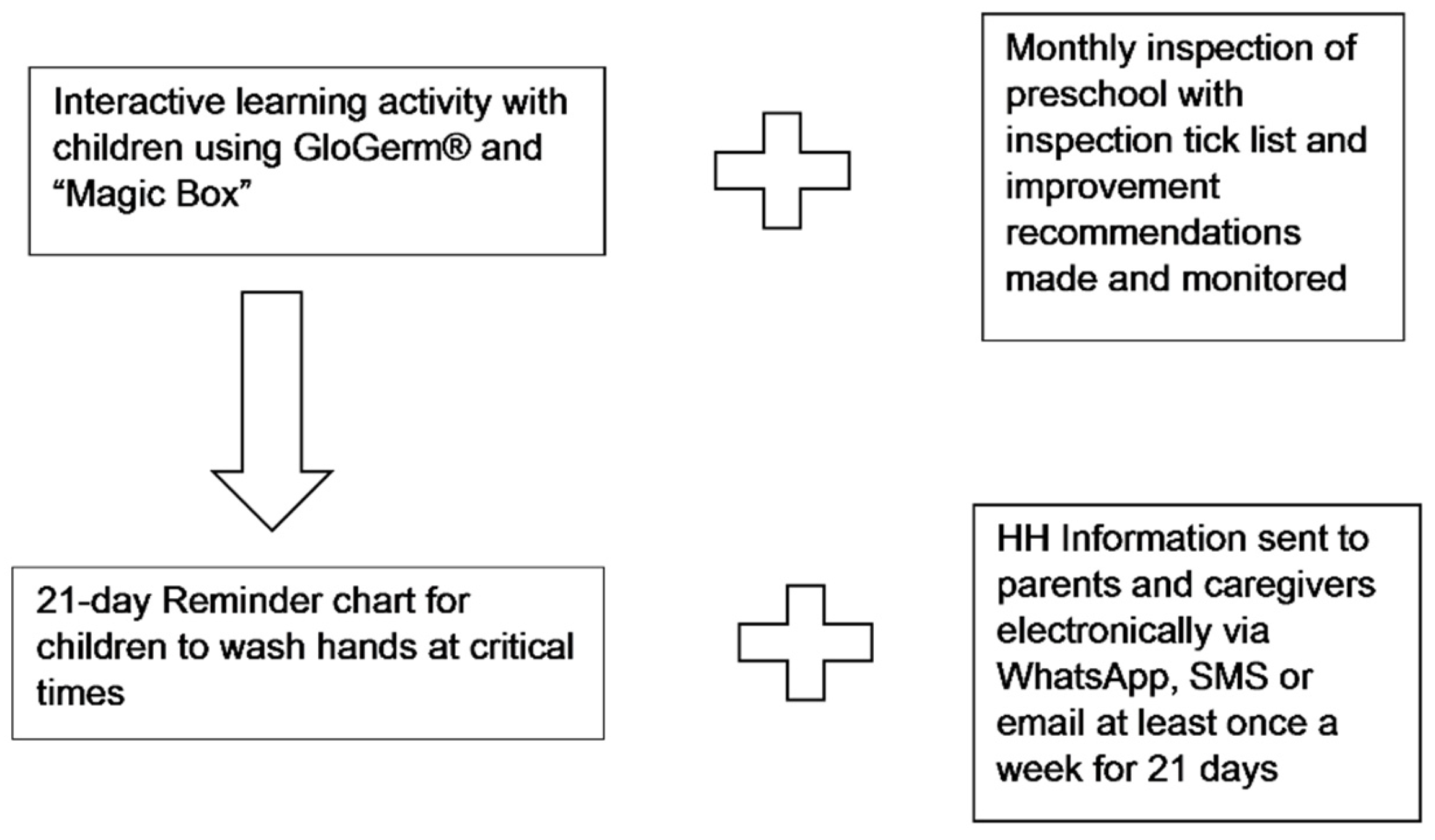

2.5. Intervention

Figure 2 provides a schematic representation of the intervention which was conducted on the IG. The intervention was administered to the children in the IG; their parents and the preschool. An interactive learning exercise was used for the children. This was conducted by the researcher using ‘simulation education’ with the application of GloGerm

®to childrens hands to simulate germ distribution. Children rubbed GloGerm

® onto their hands and then placed them into a “Magic Box” which was a black box fitted with ultraviolet black light and a viewing hole to allow children to see the “germs” glowing on their hands. They were then taught to wash their hands using the WHO method and once again, placed their hands inside the box. Correct hand washing would remove all the “germs” and they would not be visible under the ultraviolet black light. The class was also given a three week hand wash reminder chart where children placed stickers on the chart for every day they washed their hands correctly, and hand wash poster reminders to wash hands at critical times.

3. Results

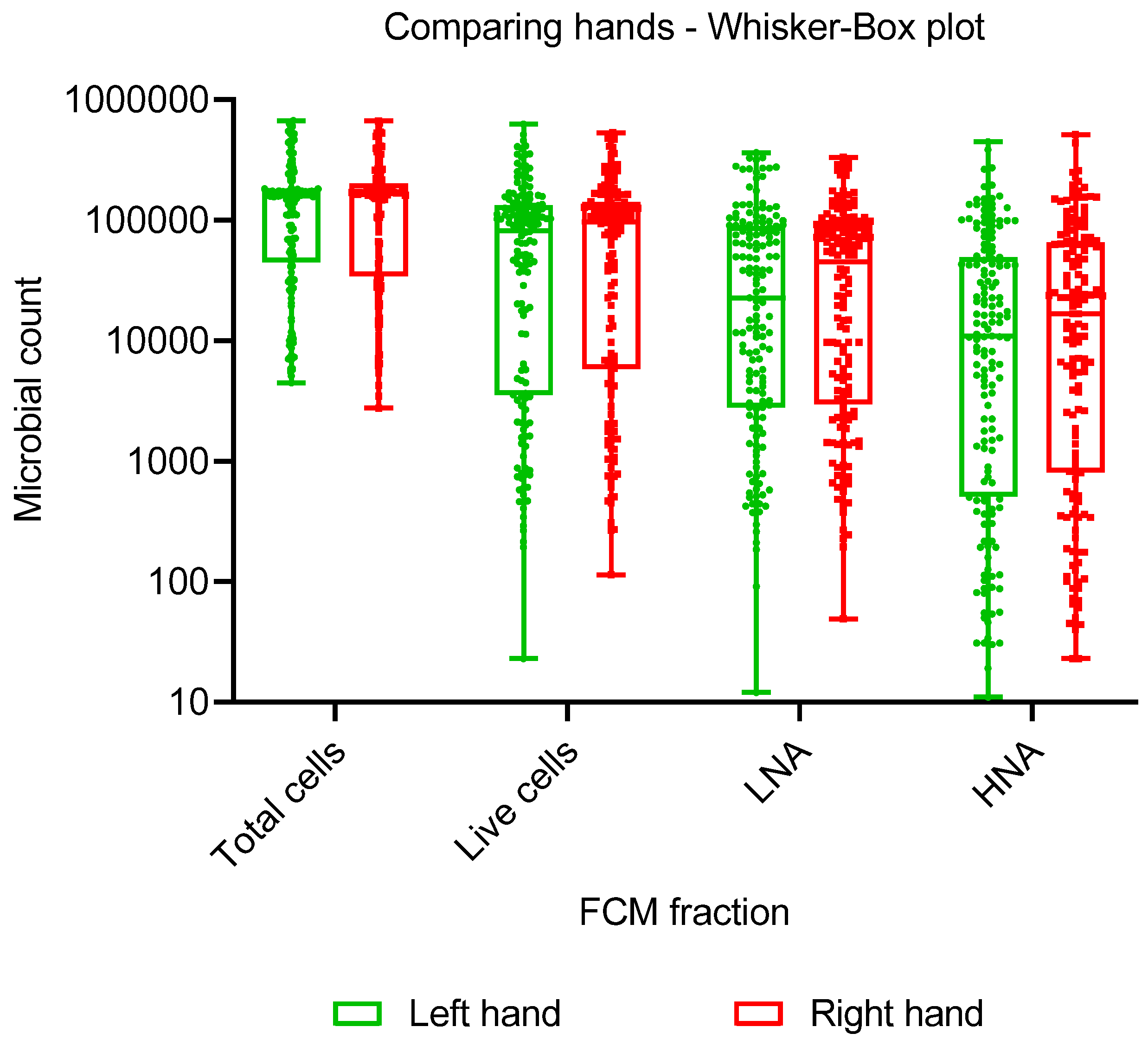

The total and intact (live) bacterial population for left and right hands as well as the distribution of Low Nucleic Acid (LNA) and High Nucleic Acid (HNA) content bacteria is illustrated in

Figure 3. The total bacterial population includes both live and damaged cells, while the intact population only represents live bacterial cells.

In

Table 1, the pre-intervention bag-wash results with combined totals and gender, showed that there was no significant difference between right and left hands (right hand

p=0.167 and left hand

p=0.325) and no difference between right and left hands in relation to gender (right hand

p=0.434 and left hand

p=0.296). Spearman’s rho non-parametric correlation coefficient indicated a moderately strong correlation between intact live cells and total bacterial count in both right (r₂=0.832;

p=0.000; N=160); left (r₂=0.815;

p=0.000; N=160) and combined hands (r₂=0.838;

p=0.000; N=160).

Post-intervention samples were drawn from 148 children (IG n=77 and CG n=71). A Spearman correlation was run to determine the relationship between the total cell count and intact live cells before and after children had washed their hands with or without using soap. There is a moderate positive correlation between the total cell count and the intact live cells (r₂=0.332) before the children went to wash their hands with a similar moderate correlation (r₂=0.557) in samples taken after hand washing. All children used soap to wash their hands if it was available. Twelve of the children from two preschools in IG did not have soap available and so were not able to use soap to wash their hands, whereas the remaining 65 children from seven preschools used the soap available to them. In CG 42 children from five preschools did not have soap and 29 children from the remaining five preschools did have access to soap.

There was a significant correlation in IG between intact live cells and total cell count before hand washing (r₂=0.306, n=77, p=0.007) while after hand washing the correlation was slightly stronger (r₂=0.566, n=77, p=0.000). The CG had a similar result with a moderate correlation (r₂=371, n=71, p= 0.001) before hand washing and a slightly stronger correlation afterwards (r₂=521, n=71, p=0.000). The mean intact live cells in all samples before hand washing was 12 x10⁷ and after hand washing reduced to a mean of 7x10⁶. The test was repeated on the children who used soap (n=99) and those who did not use soap (n=49) regardless of which group they were in. There was a significant correlation between live intact cells and total cell count (r2=0.327, n=49, p=0.022) in the hand samples of the “no soap” group before hand washing with a similar correlation (r2=0.563, n=49, p=0.000) after hand washing. The “soap” group had a moderate correlation before hand washing (r2=0.366, n=99, p=0.000) with little significant correlation afterwards (r2=0.559, n=99, p=0.000).

Turbidity before hand washing was measured in both IG and CG with mean turbidity in IG measuring 78.2179 NTU (Nephelometric Turbidity Unit) and CG 141.0746 NTU. After hand washing the turbidity mean was 27.4001 NTU for IG and 44.3429 CG. A decreased mean of 50.8178 NTU for IG and 96,7317 NTU for CG was recorded. The difference in turbidity before and after hand washing was measured in both the “soap” and the “no soap”. The mean turbidity of the “no soap” group before hand washing was 80.83734694 NTU and the “soap” group was 69.33575758 NTU. Turbidity before and turbidity after hand washing in both the “soap” and “no soap” group was analysed. There is a mean reduction of 67.0841 NTU in the “soap” group and 80.8373 NTU in the “no soap” group. There was a significant positive correlation between turbidity pre- and post- hand washing in the “No soap” group (r=0.489; N=49; sig.=0.000) and the soap group (r=0.580; N=98; sig.=0.000).

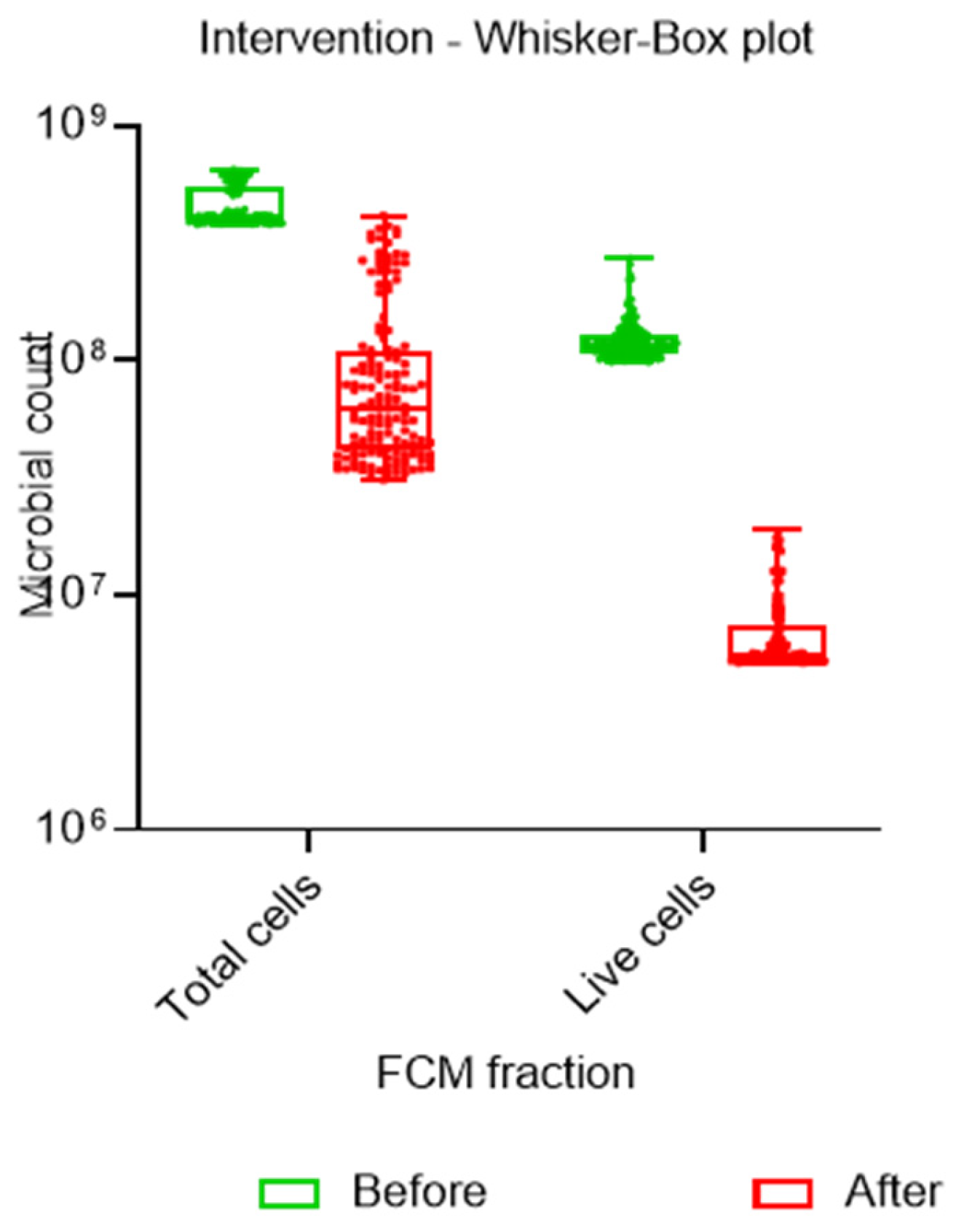

A data set was created for the results of all children whose hands were sampled prior to the intervention and post-intervention (N=148) in both IG and CG so that pre-intervention results could accurately be compared to post-intervention results. The data for total cells and total intact live cells pre-intervention was compared with total cells and total intact live cells post-intervention prior to hand washing as well as comparing to total cells and total live cells after hand washing.

Table 2 indicates the results for male and female children in IG and CG pre-intervention; post-intervention before washing hands and post-intervention after washing hands with or without soap.

A Friedman test was conducted in order to measure the three points in time to obtain a mean rank. The results of the Wilcoxon signed rank test indicated significant differences (

p=0.000) between these three results in IG and CG for the total cell count, where the post-intervention pre-hand washing total cell count was significantly different to the pre- and final post-intervention samples for both groups (

Figure 4). The same analysis was conducted on the total intact cells for the same three points in time. The result indicates a significant difference (

p=0.000) in IG between the pre-intervention, post-intervention, pre-hand washing and post-intervention post-hand washing intact live cell counts. In CG there was no significance placed on the difference in counts pre- and post-intervention (

p=0.231) but a significant difference (

p=0.000) between post-intervention pre-hand washing and post-intervention post-hand washing intact live cell counts.

The equation below was used to calculate the percentage reduction:

Where A is the number of viable microorganisms before the treatment and B is the number of viable microorganisms after treatment.

The effect size between pre- and post-intervention intact live cell count through the application of Cohen’s d indicated a medium effect (d=0.42) with a small effect (d=0.25) between post-intervention pre-hand washing and post-intervention post-hand washing intact live cell count.

4. Discussion

The results of the hand swab samples were compared to determine whether microbiological counts on hands had decreased post-intervention. Pre-intervention hand samples for both IG and CG showed no significant difference in the cleanliness of boys’ and girls’ hands which is contradictory to previous studies. These studies reported that a higher standard of hand hygiene was found in girls, especially in the under-5 age group [

22] and, that according to a meta-analysis of health behaviours in adolescents, girls washed their hands consistently more than boys [

23]. Pre-intervention hand swab samples were taken from both right and left hands to determine whether the dominant hand carried an higher microbiological load as a result of the dominant hand being used more frequently to pick up objects [

7]. According to the analysis there was no significant differene between the dominant and other hand.

Due to the results of the pre-intervention samples, post-intervention samples were collected by washing both hands together in a single bag. The purpose of these samples was to determine if the intervention had helped the IG to wash hands more effectively thereby reducing the microbiological counts on the hands of this group. In both IG and CG some preschools did not have soap available but all had running water and wash basins for hand washing. Total cell count, active live cells and turbidity was measured in samples from both groups, prior to hand washing and post-handwashing, keeping note of the “soap” and no soap” groups. There was a reduction in turbidity in both IG and CG with a positive correlation between the “soap” and “no soap” group both re- and post-handwashing. Higher fecal bacterial counts have been associated with higher levels of turbidity in hand bag wash samples of previous studies [

24] indicating that the reduced turbidity found in both groups regardless of whether they used soap or not showed that the simple mechanism of rubbing hands together with clean water as per the WHO recommended method could potentially improve hand hygiene. As there was a correlation between total cell counts and live active cells, in both groups the motion of washing and rinsing of hands in clean water could possible remove some micro-organisms from the hands, providing a similar result to a study in Indonesia which reported that children who washed hands using more motions displayed a reduction in

E.coli on the hands [

25].

Comparative analysis of results from the bag-wash samples of those children who were present for both pre- and post-intervention sampling provided an opportunity to compare a robust, valid sample as only those children who were present at both opportunities were included in the sample for this analysis. There was a significant difference in the results of the IG live intact cell counts pre- and post-intervention which was not observed in CG. As only the IG was exposed to the intervention this could indicate that the intervention assisted with improved hand washing techniques thereby dislodging live intact cells, as not seen in CG. The method of reporting differences in total cell counts and intact cell counts is a novel one, as previous literature does not report on such cell counts, but rather based results on microbial growth pre- and post- intervention as reported in a systematic review of hand contamination studies [

26].

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this paper was to discover whether a simple intervention would reduce microbial counts on the hands of pre-schoolers. Total cell count and live intact cell count has been established for these pre-school children based on gender both prior to and after washing their hands. The intervention intended to teach children the correct way to wash hands (WHO method) making use of an entertaining and cost-effective intervention. Although there was improvement in both intervention and control groups pre- and post-intervention there was a significant reduction in live cell counts in IG indicating that this group used the WHO method to better effect than CG. Washing hands either with or without soap, while using the mechanics of rubbing hands under running water can reduce microbiological counts on hands of pre-schoolers. Therefore, re-enforcing the washing of hands at critical times and ensuring correct hand washing procedures can assist in reducing hand hygiene related diseases in preschool children.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, S.L., T.G.B and N.N; methodology, S.L.; T.G.B; validation, S.L., T.G.B, N.N. and T.S.; formal analysis, S.L. T.G.B. and T.S.; investigation, S.L.; resources, T.G.B. and T.S.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, T.G.B., N.N., and T.S.; visualization, S.L and T.G.B.; supervision, T.G.B and N.N.; project administration, S.L,; funding acquisition, None. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF) Thuthuka Grant (UID:121962). .

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approved by the University of Johannesburg’s Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (REC -01-165-2017) and the Ministerial Consent for Non-Therapeutic Research on Minors for Department of Health National Ethics Research Council (GP-201804-002).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical support accorded to this study by the research staff of Water and Health Research Centre (WHRC), Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Johannesburg.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Abbreviations.

References

- StatsSA “STATISTICAL RELEASE Mortality and causes of death in South Africa: Findings from death notification 2020.”. Available online: www.statssa.gov.za, info@statssa.gov.za,Tel+27123108911.

- H. S. Waddington, E. Masset, S. Bick, and S. Cairncross, “Impact on childhood mortality of interventions to improve drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) to households: Systematic review and meta-analysis,” PLoS Med, vol. 20, no. 4, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Ray, R. Amarchand, J. Srikanth, and K. K. Majumdar, “A Study on Prevalence of Bacteria in the Hands of Children and Their Perception on Hand Washing in Two Schools of Bangalore and Kolkata,” vol. 55, no. 4, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Wilson, M. P. Verhougstraete, P. I. Beamer, M. F. King, K. A. Reynolds, and C. P. Gerba, “Frequency of hand-to-head, -mouth, -eyes, and -nose contacts for adults and children during eating and non-eating macro-activities,” J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 34–44, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Sittikul et al., “Stability and infectivity of enteroviruses on dry surfaces: Potential for indirect transmission control,” Biosaf Health, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 339–345, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. George et al., “Child Mouthing of Feces and Fomites and Animal Contact are Associated with Diarrhea and Impaired Growth among Young Children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A prospective cohort study,” 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Edmonds-Wilson, N. I. Nurinova, C. A. Zapka, N. Fierer, and M. Wilson, “Review of human hand microbiome research,” J Dermatol Sci, vol. 80, no. 1, pp. 3–12, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Clough, “Gender and the hygiene hypothesis,” Soc Sci Med, vol. 72, no. 4, pp. 486–493, 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. I. Ejemot-Nwadiaro, J. E. Ehiri, D. Arikpo, M. M. Meremikwu, and J. A. Critchley, “Hand-washing promotion for preventing diarrhoea,” Jan. 07, 2021, John Wiley and Sons Ltd. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Freeman et al., “Systematic review: Hygiene and health: Systematic review of handwashing practices worldwide and update of health effects,” Tropical Medicine and International Health, vol. 19, no. 8, pp. 906–916, 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, L. Ran, Q. Liu, Q. Hu, X. Du, and X. Tan, “Hand hygiene, mask-wearing behaviors and its associated factors during the COVID-19 epidemic: A cross-sectional study among primary school students in Wuhan, China,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 17, no. 8, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Teirilä et al., “Hand washing with soap and water together with behavioural recommendations prevents infections in common work environment: an open cluster-randomized trial,” Trials, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Stangerup et al., “Hand hygiene compliance of healthcare workers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A long-term follow-up study,” Am J Infect Control, vol. 49, no. 9, pp. 1118–1122, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Ragusa, M. Marranzano, A. Lombardo, R. Quattrocchi, M. A. Bellia, and L. Lupo, “Has the covid 19 virus changed adherence to hand washing among healthcare workers?,” Behavioral Sciences, vol. 11, no. 4, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Wolf et al., “Effectiveness of interventions to improve drinking water, sanitation, and handwashing with soap on risk of diarrhoeal disease in children in low-income and middle-income settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” The Lancet, vol. 400, no. 10345, pp. 48–59, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kim and O. Lee, “Effects of Audio-Visual Stimulation on Hand Hygiene Compliance among Family and Non-Family Visitors of Pediatric Wards: A Quasi-Experimental Pre-post Intervention Study,” J Pediatr Nurs, vol. 46, pp. e92–e97, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu et al., “A hand hygiene intervention to decrease hand, foot and mouth disease and absence due to sickness among kindergarteners in China: A cluster-randomized controlled trial,” Journal of Infection, vol. 78, no. 1, pp. 19–26, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Watson et al., “Effect of a novel hygiene intervention on older children’s handwashing in a humanitarian setting in Kahda district, Somalia: A cluster-randomised controlled equivalence trial,” Int J Hyg Environ Health, vol. 250, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Lange, “THE EFFECT OF A SIMPLE INTERVENTION ON HAND HYGIENE RELATED DISEASES IN PRESCHOOLS,” Doctoral thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2021.

- S. L. Lange, T. G. Barnard, and N. Naicker, “Effect of a simple intervention on hand hygiene related diseases in preschools in South Africa: Research protocol for an intervention study,” BMJ Open, vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 1–8, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Singh, C. J. Yelverton, and T. G. Barnard, “Rapid Quantification of the Total Viable Bacterial Population on Human Hands Using Flow Cytometry with SYBR® Green I,” Cytometry B Clin Cytom, vol. 96, no. 5, pp. 397–403, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Clough, “Gender and the hygiene hypothesis,” Soc Sci Med, vol. 72, no. 4, pp. 486–493, 2011. [CrossRef]

- W. R. De Alwis, P. Pakirisamy, L. Wai San, and E. C. Xiaofen, “A Study on Hand Contamination and Hand Washing Practices among Medical Students,” ISRN Public Health, vol. 2012, no. Cdc, pp. 1–5, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Pickering, T. R. Julian, S. Mamuya, A. B. Boehm, and J. Davis, “Bacterial hand contamination among Tanzanian mothers varies temporally and following household activities,” Tropical Medicine and International Health, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 233–239, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Rifqi et al., “Effect of handwashing on the reduction of Escherichia coli on children’s hands in an urban slum Indonesia,” J Water Health, vol. 21, no. 11, pp. 1651–1662, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Cantrell et al., “Hands Are Frequently Contaminated with Fecal Bacteria and Enteric Pathogens Globally: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” May 17, 2023, American Chemical Society. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).