1. Introduction

Traditional energy sources are losing their effectiveness globally due to their environmental damage, time-consuming depletion, and production challenges. In this context, countries and societies are turning their attention to renewable energy. Renewable resources, which can be considered new, are rapidly advancing and developing.

Renewable energy systems are relatively new to the world. Therefore, they need to be incentivized to increase their deployment and include communities in their installations. These incentives should be high enough to attract widespread attention at the initial stage and to adapt to market conditions over time. Therefore, countries need to approach global standards in renewable energy installations and provide the right and sufficient incentives to keep pace with this global renewable energy trend.

Research conducted in this context examines incentive systems. These studies: In a study that analyzes the policies implemented in EU countries and the compatibility of these policies, the compatibility of incentives has been examined [

1], in another study, renewable incentive policies have been evaluated by comparing EU countries and US states [

2], in another study, the effectiveness of FIT, quota system and green certificates in EU countries has been examined [

3], in a study conducted on the example of Malaysia, a study has been conducted that matches Malaysia’s renewable energy progress and renewable energy status in the last 10 years [

4], FIT, tax incentives and green certificates that can be applied to reduce carbon emissions have been examined in detail and their effectiveness has been examined [

5], in a study that offers an analysis for successful penetration of policy makers and renewable energy investors, incentives are analyzed depending on the country and for different sectors [

6], in another study, renewable energy incentives; FIT, green certificates, auctions and net metering systems have been analyzed in detail and their effectiveness has been examined. Latin American countries were analyzed in comparison with Brazil [

7]. A study conducted in five selected EU countries analyzed the effectiveness of incentives and examined how much of an increase in incentives increased production [

8]. A study conducted in EU countries analyzed the biogas policy area in depth and offered suggestions that could provide solutions to the complex structure of this area. These suggestions are presented in comparison with other countries [

9]. Another review study presents an examination of sustainable energy policy for the promotion of renewable energy by introducing the development history of energy policy in five countries, namely the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, Denmark, and China [

10]. A study conducted in Iran aims to examine trends in energy demand, policies, and the development of renewable energies, and the causal relationship between renewable and non-renewable energies and economic growth using two methodologies [

11]. A study conducted in Turkey examines the general status of renewable energy sources in different countries, and Turkey, and the incentive methods given for the production of electrical energy from these sources [

12]. This study provides a comparative analysis of the current state of renewable energy in selected EU countries and Turkey, their future provisions and targets, the incentives and policies implemented to achieve these targets, and the impact of renewable policy implementation rates on national renewable energy success. The incentive methods employed are analyzed and explained, along with the ways they are implemented in these countries. This study examines the renewable energy status, incentives, and future provisions of selected countries and Turkey, and presents the findings for policymakers, academic researchers, and industry representatives. Unlike other studies, this study examines the main incentive models implemented in the EU region, using a broader selection of countries, presenting Turkey’s incentive and policy developments over time, and conducting a comparative analysis. Previous academic studies have focused on a narrower sample size of countries and incentive methods. While a single incentive method or a few are analyzed, this study broadens the scope of both countries and incentive methods. While other studies analyze different countries and regions, this study conducts a comparative analysis of Turkey and EU countries. Turkey’s low renewable energy level, despite its high renewable capacity and installed electricity capacity, was analyzed. Data obtained from an extensive literature review were analyzed comparatively for Turkey and EU countries.

2. EU Countries and Turkey Renewable Energy Status and Future Provision

The European Union is home to approximately 6% of the world’s population. It meets approximately 10% of global energy demand. The European Union’s population is expected to reach 425 million in 2050, with a GDP of $35.1 trillion, and the goal of achieving net zero by 2050. The goal is to eliminate fossil fuel dependency by 2050.

-

A.

Germany

Current Status: Germany’s installed capacity is approximately 235 GW by 2025. Wind energy accounts for approximately 34% of this capacity, solar energy 14%, and biomass and other renewable resources 8.4% [

13].

By 2024, Germany will meet approximately 56% of its energy production from renewable sources.

Future Provision: Germany aims to generate 80% of its energy production from renewable sources. The deadline for this target is 2030. Furthermore, the goal of climate neutrality is aimed at achieving the 2045 vision. Germany’s ultimate renewable energy vision is 2035. This vision aims to meet all of its energy demand from renewable sources.

-

B.

France

Current Status: FranCE has an installed capacity of 136 GW by 2024. 72% of this will be nuclear energy, 10% hydroelectricity, 8% wind energy, 4% solar energy, and 6% fossil fuels (IEA).

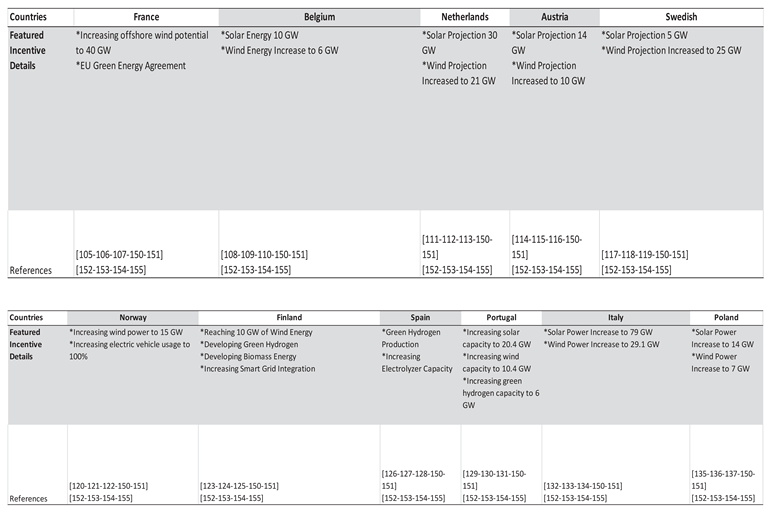

Future Provision: France has adopted the goal of becoming carbon-neutral by 2050. It aims for renewable energy to account for 40% of its total installed capacity by 2030. It plans to increase its offshore wind energy potential to 40 GW. France is making all these plans to meet the EU Green Deal standards.

-

C.

Belgium

CurrentStatüs: The total installed capacity in Belgium is 22 GW. 35% of this is natural gas and fossil fuels, 22% wind energy, 30% solar energy, 10% nuclear energy, and 3% other energy sources [

17]. Future Provision: Belgium’s future provision includes visions for 2030 and 2050. The 2030 targets include reducing gas emissions by 55%, increasing renewable energy to 42%, increasing wind capacity to 6 GW, and increasing solar power to 10 GW. The 2050 targets include achieving carbon neutrality and generating all energy from renewable sources, increasing offshore wind power to 11 GW, increasing the use of green hydrogen, and transforming North Sea islands into energy islands.

-

D.

Netherlands

Current Status: The Netherlands has a total installed capacity of approximately 45 GW. 40% of this comes from natural gas and fossil fuels, 21% from wind energy, 33% from solar energy, and 5% from biomass energy.

Future Provision: The Netherlands has two visions for renewable energy: 2030 and 2050. The 2030 goals include reducing carbon emissions by 55%, increasing the share of renewable energy to 70%, increasing wind energy to 21 GW, and increasing solar energy to 30 GW by activating rooftop projects [

18]. The 2050 goals include becoming a carbon-neutral country, establishing large-scale energy storage systems, and increasing energy efficiency by increasing smart grids.

-

E.

Austria

Current Situation: Austria’s installed capacity is approximately 28 GW. This consists of 53% hydroelectric power, 14% wind power, 11% solar power, 7% biomass energy, and 15% natural gas and fossil fuels.

Future Provision: Austria has adopted the 2030 and 2050 future provision targets. The 2030 targets include utilizing 100% renewable energy sources, increasing wind power to 10 GW, solar power to 14 GW, and installing energy storage systems. The 2050 targets include neutralizing carbon emissions, increasing green hydrogen production, and aligning with the EU Green Deal [

19].

-

F.

Swedish

Current Situation: Sweden’s installed capacity is approximately 47 GW. This includes 36% hydroelectric power, 18% nuclear power, 32% wind power, 3% solar power, and 11% biomass and other energy sources.

Future Provision: Sweden has visions for renewable energy for 2030 and 2045. The 2030 vision includes increasing the renewable share to 90%, reaching 25 GW in wind power, increasing solar power to 5 GW, converting all vehicles to electric vehicles, developing energy storage systems, and increasing green hydrogen production. 2045 targets include transitioning to a 100% renewable, carbon-neutral energy system, increasing wind power capacity to over 50 GW, providing all industrial and residential heating with renewable energy, and increasing energy trade with Northern European countries.

-

G.

Norway

Current status: Norway’s total installed capacity is approximately 43 GW. This comprises 83% hydroelectric power, 11% wind power, 0.5% solar power, 2% biomass and other energy sources, and 4% natural gas and fossil fuels [

21].

Future Provision: Norway has renewable energy visions for 2030 and 2050. The 2030 vision targets include transitioning to fully renewable energy, reaching 15 GW of wind energy, increasing the use of renewables in transportation, developing energy trade with Nordic countries, and increasing the use of electric vehicles to 100%. The 2050 vision aims to transition to a carbon-neutral energy system, increasing the North Sea energy potential to 50 GW, increasing green hydrogen production, increasing the capacity of energy storage systems, and increasing renewable energy efficiency in the industry, transportation, and residential sectors [

21].

-

H.

Finland

Current status: Finland’s total installed capacity is 18 GW. Of this, 26% is nuclear energy, 29% is wind energy, 19% is hydroelectric energy, 19% is biomass and other energy sources, and 7% is natural gas and fossil fuels.

Future Provision: Finland has visions for 2035 and 2050. The 2035 vision includes becoming a carbon-neutral country, reaching 10 GW of wind energy, developing sustainable forest management for biomass energy, increasing solar energy efficiency in cities and industry, and developing green hydrogen production [

22,

23]. The 2050 vision includes the development of green hydrogen, increasing smart grid integration, increasing energy exchanges with Northern Europe, and zeroing out carbon emissions by switching to a circular energy model.

-

I.

Spain

Current Status: Spain’s installed capacity stands at approximately 118 GW. Approximately 25% of this comes from solar energy, 25% from wind energy, 17.23% from hydroelectricity, 6.12% from nuclear energy, and 25.84% from other sources. Future Provision: Spain has a 2030 vision as its future goals. Within this scope, Spain aims to increase the share of renewable resources in its total energy resources to 81%. Green hydrogen production is also among Spain’s main agenda items. The aim is to increase its electrolyzer capacity to 11 GW by 2030.

-

J.

Portugal

Current Status: Portugal has a total installed capacity of 20.7 GW. Approximately 35% of this comes from hydroelectric power, 27.1% from wind power, 13.1% from solar power, and 24.5% from other sources.

Future Provision: Portugal has a 2030 vision as its future goal. This vision aims to meet 85% of its electricity consumption from renewable sources. It also aims to increase its installed solar power capacity to 20.4 GW, increase its green hydrogen capacity to 6 GW, and increase its installed wind power capacity to 10.4 GW.

-

K.

Italy

Current status: Italy’s installed capacity is known to be approximately 120 GW. This consists of 42% natural gas, 18% hydroelectricity, 7% wind energy, 9% solar energy, 2% biomass energy, 9% coal energy, and 13% other sources.

Future Provision: Italy has a 2030 vision for renewable energy. Within the scope of this vision, it aims to provide 65% of its electricity consumption from renewable sources by 2030. It aims to increase solar capacity to 79 GW and wind energy to 28.1 GW by 2030 [

26,

28].

-

L.

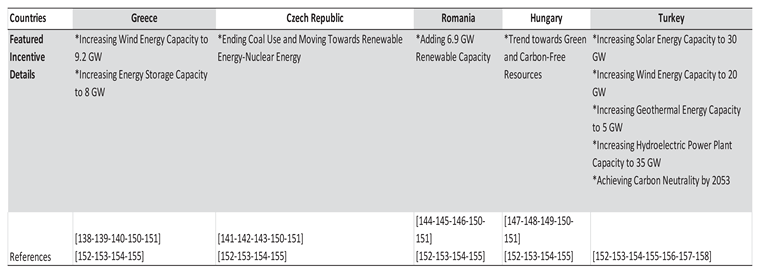

Greece

Current status: Greece has approximately 34.7 GW of installed electricity capacity. Approximately 23.5% of this comes from lignite, 28% from natural gas, 19.1% from hydroelectricity, and 29.3% from renewable energy sources.

Future Provision: Greece has a 2030 renewable energy vision. This vision aims to increase total renewable energy capacity to 28 GW by 2030, energy storage capacity to 8 GW, and wind energy capacity to 9.2 GW [

30].

-

M.

Poland

Current Status: Poland has approximately 65 GW of installed electrical capacity. Of this, 70% is coal energy, 16.9% is renewable energy, and 13.1% is natural gas.

Future Provision: Poland has a 2030 renewable energy vision. Within the scope of this vision, it is planned to increase its renewable energy capacity to 22 GW by 2030. Solar energy is planned to reach approximately 14 GW, and wind energy to 7 GW [

31].

-

N.

Czech Republic

Current Status: The Czech Republic has an installed capacity of approximately 22 GW. This consists of 50% coal, 35% nuclear energy, and 15% renewable energy sources.

Future Provision: The Czech Republic has a 2033 energy vision. Within the scope of this vision, it plans to phase out coal use by 2033. It is planned to replace coal with nuclear and renewable energy sources [

32].

-

O.

Romania and Hungary

Current Status and Future Provisions: Romania has an installed capacity of approximately 24 GW. This capacity consists of 30% coal power plants, 25% natural gas, 20% hydroelectric power plants, 15% wind energy, and 5% solar energy. Romania has a 2030 vision, which plans to add 6.9 MW of renewable capacity by 2030. Hungary has an installed electricity capacity of approximately 8.5 GW. This capacity consists of 50% nuclear power sources, 20% natural gas sources, 15% coal sources, and 15% renewable energy sources. Hungary has a 2030 renewable energy vision. Within the scope of this vision, the company aims to generate electricity from green and carbon-neutral sources by 2030.

-

P.

Turkey

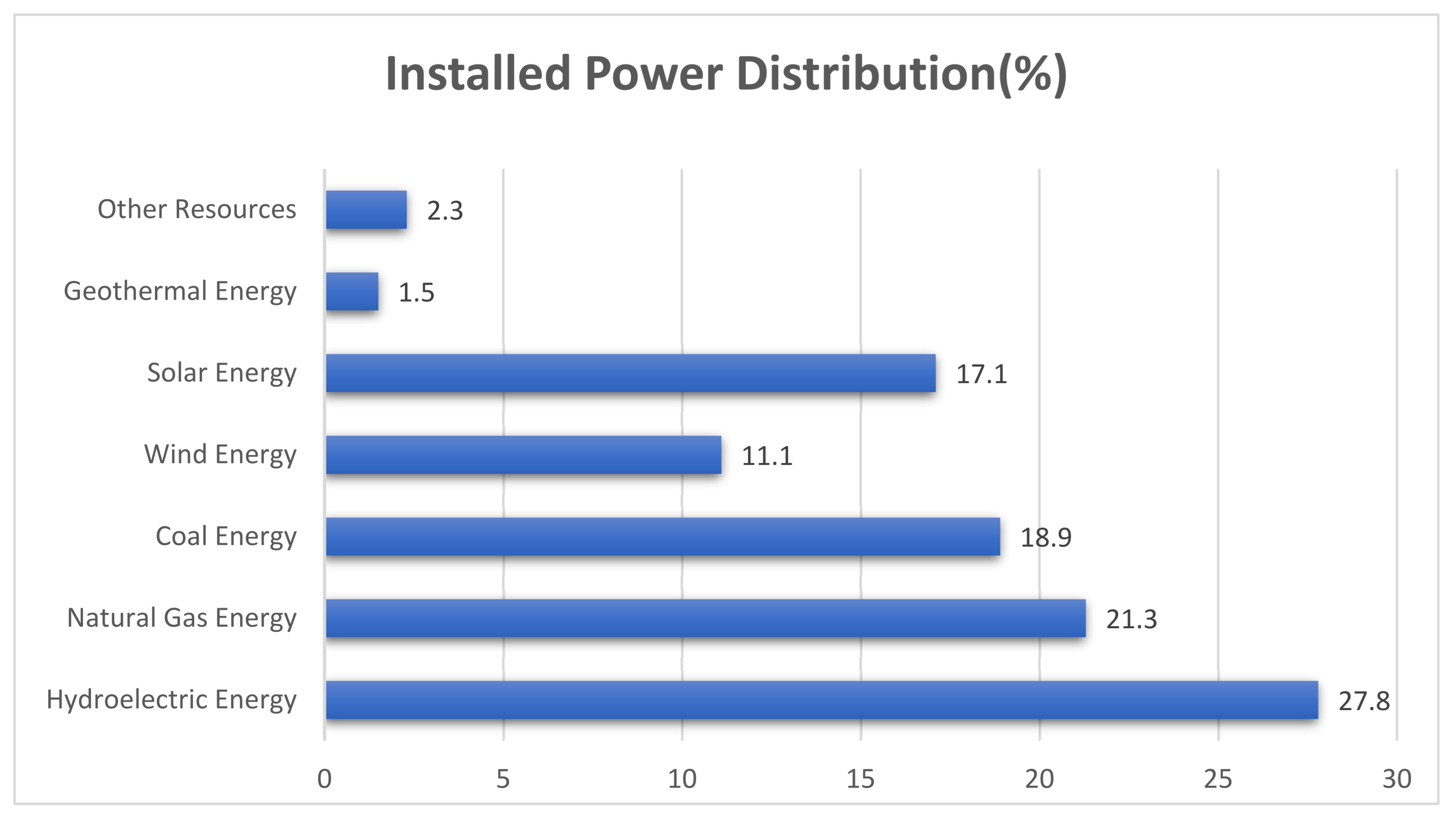

Turkey’s installed capacity is approximately 116 GW, according to December 2024 data. This represents 27.8% hydroelectric power, 21.3% natural gas, 18.9% coal, 11.1% wind, 17.1% solar, 1.5% geothermal, and 2.3% other sources. In 2024, an installed capacity increase of 6.5 GW was achieved, 99% of which came from renewable energy sources.

Future Provision: Turkey has visions for 2023, 2030, and 2053. The 2030 vision aims to increase solar energy capacity to 30 GW, wind energy capacity to 20 GW, geothermal energy capacity to 5 GW, and hydroelectric energy to 35 GW. The goal is to increase the proportion of renewable energy in national energy to 60% by 2030. The 2053 vision aims to have a carbon-neutral energy system [

36].

Figure 1.

Installed Power of Turkey.

Figure 1.

Installed Power of Turkey.

3. Analysis of Renewable Energy Incentives and Policies Implemented in EU Countries and Turkey

Incentives that facilitate the expansion of renewable energy systems in EU countries are divided into eight main groups. These are: Feed-in Tariff, Feed-in Premium (FiP), Green Certificates, Tax Incentives, Investment Grants, Net Metering, Tender and Competitive Incentive Systems, and Special applications.

3.1. Feed-in Tariff (FIT)

This system provides investors with a guaranteed purchase price for the energy produced by renewable energy systems. This incentive system limits the purchase guarantee to a fixed number of years, and the purchase price is fixed regardless of market conditions. This rationalizes the economic feasibility of the investment and increases predictability. The EU countries where FIT incentives are used and their prominent features are shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Feed-in Premium (FIP)

These are systems that provide premiums in addition to the market price of electricity. These premiums, in addition to the market price, shorten the investment amortization period and make investment feasibility more attractive [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. The EU countries where FIP incentives are used and their prominent features are shown in

Table 2.

3.3. Tax Incentives

These are systems that provide tax exemptions for investments. VAT exemptions and equipment investment incentives are implemented [

53,

54,

55,

56].

Advantage: Shortens investment amortization period, reduces lifecycle costs, and provides investors with an economically predictable investment environment.

Disadvantage: Creates a long-term economic burden on public finances.

Example European Countries: Denmark, the Netherlands, Italy.

3.4. Certificate Supports

This system grants certificates to industry representatives. These certificates are also made legally obligatory, thus supporting renewable energy [

57,

58,

59,

60].

Advantage: With the certificate requirement, investments are market-driven. The investment budget is not provided by the public sector. It does not create an economic burden on the public sector.

Disadvantage: If implemented as a standalone incentive policy, a competitive incentive system cannot be achieved.

Example European Countries: Belgium, Sweden, Norway, Poland.

3.5. Investment Supports

These are financial supports provided directly to investors. Low-interest loans reduce initial investment and depreciation costs for investors and lower financing costs [

62,

63,

64].

Advantage: Reduces initial investment and financing costs.

Disadvantage: Creates a financial burden on the public budget and public banks.

Applied Example European Countries: Finland, Austria, Czech Republic.

3.6. Net Metering

These systems establish a balance between production and consumption. Produced energy is primarily used for domestic consumption, while excess energy is fed into the national grid. Here, the energy supplied to the national grid is paid to investors via a fixed payment method. This incentive system is generally implemented in conjunction with the FIT system. It is implemented with a 10- to 20-year purchase guarantee [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69].

Advantage: The purchase guarantee offers investors a predictable income model. Because it is demand-oriented, it reduces national grid line congestion, as this system is generally connected to the grid through distribution lines.

Disadvantage: It creates a financial burden on the public budget. Because it requires connections from different points of the grid, it can negatively impact grid dynamics and cause electrical harmonics.

Example European Countries: Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, etc.

3.7. Tender Incentives

Renewable systems are made available to investors en masse through publicly held tenders. This allows for large-scale, collectively-constructed projects and competitive incentive systems [

70,

71,

72,

73].

Advantage: Large installations are organized at minimal costs.

Disadvantage: Small investors are excluded from the system, and projects proceed solely under the monopoly of large investors.

Example European Countries: Spain, Portugal, Greece, etc.

3.8. Special Projects

These are specially designed incentive systems that support rooftop systems, microgrids, small projects under a certain power level, and SMEs.

Advantage: By supporting small projects, projects become more attractive to end users. Because incentives are broken down into smaller units, the pace of renewable energy system installation is faster.

Disadvantage: As the rate of connection to the system increases for smaller users, monitoring of incorrect installations becomes more difficult, and grid disruptions may increase, leading to increased grid harmonics.

Example European Countries: United Kingdom, Switzerland, Hungary.

3.9. Carbon Trading Credit Incentive

Under the carbon trading system, renewable energy investors earn carbon credits for reducing carbon emissions. These carbon credits can be used for commercial purposes. This system is implemented in Romania and Hungary.

4. Regional and Country-Specific Evaluation of Incentives and Policies Implemented by the EU Region and Turkey

Living conditions vary across regions within the European Union. This section examines regional differences and their key characteristics.

4.1. Western Europe

It is the region that includes Germany, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Austria. Its main characteristics are shown in

Table 3.

-

A.

Germany

German renewable energy incentives and policies date back to 2000. The renewable energy law was adopted, and legal incentives were established.

In this context, the fixed feed-in tariff (FIT), grid priority, auction system, investment supports, tax incentives, financing supports, and R&D incentives were implemented [

74].

Incentives were provided by prioritizing renewable resources for grid connection, and the fixed feed-in tariff determined the number of years for purchases. The purchase guarantee was provided for 20 years. Purchase prices are provided at 8 euro cents per kWh. Specific applications for scaled systems are also being implemented in Germany. For installations up to 10 kW, incentives of 10-11 euro cents per kWh are applied, and for installations up to 40 kW, incentives of 9-10 euro cents per kWh are applied. For large systems (up to 1 MW), incentives of 7-8 euro cents per kWh are applied. For biogas plants, this value increases to 13-15 euro cents.

Germany implements an auction incentive system for large projects. Thus, the purchase guarantee value is determined by the auction method. A local and regional incentive system is also in place in Germany. Municipalities are also provided with special support for small projects. Emission incentives encourage renewable energy investments in institutions.

-

B.

France

Primarily, public support programs include tax exemptions, tender support mechanisms, and R&D support.

France provides €11 billion in financing for offshore wind energy projects. Furthermore, tender support encourages mass installations. Tender initiatives were held in 2021 and 2022, resulting in the allocation of 4.2 GW of capacity. 931 MW of wind power plant capacity has also been allocated to onshore wind energy installations [

75].

-

C.

Belgium

Renewable energy incentives in Belgium are categorized as certificate incentives, tax incentives, grant incentives, R&D support, and cooperative incentives.

Under the certificate system, energy supply companies are required to source a certain portion of their energy from renewable sources. This incentive system has been implemented in Flanders and Wallonia. Tax incentives include VAT exemptions, income tax reductions, and property tax exemptions.

Belgium supports offshore wind power plants through grant incentives. In this context, a 700 MW wind farm project in the North Sea was approved, and a government grant of €682 million was provided. Belgium is the first European country to support and implement offshore floating energy projects.

Belgium provides separate support to energy cooperatives. Cooperatives are gaining prominence as systems whose use will increase globally in the coming years [

76].

-

D.

Netherlands

The Netherlands implements financial, tax, and financing support as renewable energy incentives. The SDEE+ program provides support for solar, wind, geothermal, and biomass energy systems. In this context, 4,400 MW power plants have been financially supported. VAT exemption incentives have exempted renewable energy plants from the 21% VAT. Low-interest loans are provided for projects as investment and financing support. The Dutch Development Bank supports projects in this context [

77].

-

E.

Austria

Renewable energy incentives in Austria: VAT exemptions, financial subsidies, incentives for hydrogen distribution and storage systems, and sector-specific incentives are being implemented.

Incentives related to renewable energy use are being provided in the agricultural sector. In this context, €100 million in incentives have been provided until 2025.

The VAT exemption is implemented in the form of a zero rate. Initially, VAT was zeroed for solar energy systems.

4.2. Northern Europe

Northern Europe encompasses Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Denmark. Different incentive policies are implemented within the region, depending on regional and national conditions. The main characteristics of Northern Europe in terms of incentives and policy are shown in

Table 4.

-

A.

Sweden

Sweden uses green certificate programs, financial supports, tax exemptions, R&D supports, and public-private projects as renewable energy incentives [

79].

With FIP incentives, producers receive a green certificate for every MW they produce. They generate income by selling these certificates. VAT exemptions and income tax incentives are used as tax incentives. Wind, solar, and biogas facilities are prioritized in these incentives. Large projects are incentivized through a public-private tender system. The FIP system provides additional payments to the market price.

-

B.

Norway

Norway effectively uses renewable energy certificate incentives. Investors are offered the opportunity to sell these certificates in the free market, generating additional income [

80]. Investors are provided with financial support through low-interest loans. Tax exemptions are also used as a renewable energy incentive system.

-

C.

Finland

Finland primarily uses two incentive systems: FIT and tax incentives. FIT agreements are made based on a predetermined market price. However, this value is updated based on market prices. This provides predictability for investors [

81]. An incentive system has been additionally detailed for projects undertaken in small-scale and rural areas.

4.3. Southern Europe

The main characteristics of Northern Europe in terms of incentives and policy are shown in

Table 5.

-

A.

Spain

Tax incentives, financial credit incentives, small-scale project incentives, and R&D incentives are implemented in Spain.

VAT support is applied to solar energy equipment and energy storage elements. Income tax exemptions are also among the implemented systems [

82].

Rooftop PV system support and individual production facilities are also included in Spain’s incentive systems. VAT exemptions are applied to rooftop systems and individual systems. A 30% tax reduction is offered to individuals who establish their production systems in residences.

Municipalities provide exemptions from construction permit taxes and property taxes for renewable energy facilities.

A microfinancing model is implemented for small-scale projects. Low-interest financing is provided for these projects through a joint EU-Spain partnership.

-

B.

Italy

Three main incentive policies are implemented in Italy: FIT (Fit), tax incentives, and green certificate systems.

Italy stands out in the FIT system with its contracts for difference. Contracts for difference and an auction incentive model are implemented. Thus, a system that provides bilateral offsetting and covers consumers’ electricity costs is being established [

83].

The Conto Energia program is among the incentives implemented. These incentives are also broken down specifically for rooftop systems.

-

C.

Portugal

Portuguese renewable energy incentives primarily consist of tax reductions, financing supports, tendering, and net metering systems.

Renewable energy investors are provided with low-interest funding, VAT exemptions on renewable energy equipment, and income and corporate tax reductions [

84]. Direct grants are provided for wind, solar, and biomass energy. Small investors are supported through microfinance programs. A net metering system is in place. This system provides incentives to achieve the goal of self-sufficiency.

-

D.

Greece

Greece utilizes incentives such as FIT, contracts for difference, tax exemptions, financing and grant programs, and R&D support in its renewable energy systems.

The FIT program is applied to small-scale projects and provides a fixed purchase guarantee. These incentives are heavily focused on micro solar and wind power generation facilities [

85].

Market forecasting has increased through the contract for difference method. Predetermined purchase prices are indexed to market prices, increasing market flexibility.

Tax incentives include VAT exemptions, property tax reductions, and corporate tax reductions.

Financing and grant support include low-interest loans and EU-area support, which are provided as direct subsidies to investors.

4.4. Eastern Europe

The main characteristics of Eastern Europe in terms of incentives and policy are shown in

Table 6.

-

A.

Poland

Poland benefits from EU area support for renewable energy incentives. The EU has provided Poland with €22.5 billion in support for wind energy investments. These funds are needed for the construction of wind power plants in the North Sea.

Poland has the National Renewable Energy Support System (RES), which offers a fixed price and purchase guarantee for renewable energy. This program has created predictable market conditions for investors. The purchase guarantee and fixed price support in the RES system are valid for 15 years. Surplus energy produced can be sold to the national grid at a fixed purchase price for 15 years [

86]. Poland provides investment incentives and tax exemptions for renewable energy facilities. Furthermore, through the green certificate system, investors are granted certificates that they can sell on the free market.

Poland refunds the full VAT levied on renewable energy equipment, thus providing VAT exemption.

-

B.

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic provides fixed price support to renewable energy investors. The fixed purchase support was reduced from approximately USD 0.55-0.60 per kWh of renewable energy to USD 0.12-0.20 as of 2014 [

87].

The Czech Republic provides renewable energy investors with priority connection to the national grid. This priority granted during grid connection supports renewable energy installations.

In addition to the fixed purchase guarantee, the Czech Republic organizes renewable energy tenders for large-scale projects. This reduces the public burden by offering the most favorable purchase prices and increases the number of large-scale projects.

-

C.

Hungary

The FIT system is a leading renewable energy incentive system in Hungary. The purchase guarantee period is set at 15 years. Another incentive system implemented is the tender system. This tender system reduces the public burden and rapidly increases the level of renewable energy installations with large-scale projects [

88].

Hungary also implements a VAT exemption system for renewable energy investments. VAT refunds on renewable energy investments are granted subject to certain conditions.

Hungary also effectively utilizes the Green Certificates system. The green certificates issued are converted into cash at market conditions. Hungary externally supports hybrid systems. Hungary also provides low-interest loans and funding for renewable energy investments.

-

D.

Romania

Romania’s renewable energy incentives include FIT (FIT), Green certificates, investment incentives, tax incentives, and a carbon trading system [

88].

Under the green certificate system, renewable energy producers receive certificates and can use these certificates in the free trade market.

The FIT system and fixed purchase guarantee are among the incentives provided to investors. The purchase guarantee is valid for 15 years. Low-interest credit support is provided as an investment incentive. Incentives are being increased, especially for projects in rural areas. Under the carbon trading system, renewable energy producers earn carbon credits for reducing carbon emissions and can generate income through trading with these credits.

4.5. Turkey

Turkey is among the countries with high external dependence on energy. Therefore, supply diversification policies are vital. In this context, Turkey is among the countries that should focus heavily on renewable energy. Turkey established the first legal regulation to provide incentives for renewable energy with the “Law on the Use of Renewable Energy Resources for the Purpose of Generating Electricity” enacted in 2005. Incentive mechanisms, which were not fully implemented until 2013, began to be incentivized with legal amendments and capacity allocations implemented this year. This law incentivized solar systems, followed by wind energy systems, hydroelectric production systems, geothermal energy systems, and biomass energy systems. These incentive values are shown in

Table 7. These incentive models are categorized according to whether domestically produced equipment is used or not [

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95].

Incentives initially implemented in Turkey include VAT exemptions for purchasing investment equipment from domestic or international sources, customs duty exemptions, an 85% discount on power transmission line usage fees during the investment and operation phases, a 10-year purchase guarantee of 13.3 cents/USD, and incentives for using domestic products. These incentives and practices are valid for power plants commissioned until December 31, 2019. The unit energy (KWh) incentive value can reach higher values for the use of domestically produced equipment. These incentives accelerate installations. This is illustrated in

Table 7 and

Table 8.

Domestic cell production in Turkey is expected to begin in 2023. Domestic panel production accelerated after 2012. Many domestic production companies were established and began production. Therefore, the full implementation of this incentive model was delayed, and new legislative revisions were implemented before full implementation was achieved [

96,

97,

98,

99,

100]. In 2016, the YEKDEM mechanism was implemented, establishing a centralized management organization. In 2017, large-scale projects were supported through tenders through Renewable Resource Areas (YEKA) tenders. This reduced the public burden, and large projects began to be tendered with lower purchase prices. In 2020, YEKDEM purchase guarantee prices were updated in Turkish Lira and in line with market conditions. After 2023, self-consumption incentives for rooftop systems were introduced, enabling offsetting and imposing a self-consumption obligation. This aimed to reduce the transfer of excess electricity to the grid [

101,

102].

These revisions accelerated in 2019 and 2022, and the most recent legislative revision was implemented on August 11, 2022.

These incentives underwent some revisions with the regulation issued on May 12, 2019.

These are summarized below.

Regulations made within the scope of the Unlicensed Electricity Generation Regulation in the Electricity Market emphasized the possibility of rooftop and facade solar power installations. This has shifted the focus to rooftop systems.

The new regulation allows businesses and citizens to install projects without the need to establish a company or obtain a license.

The sale of self-consumption surpluses from energy installed up to 10 kW for residential subscribers and up to 5 MW for all businesses and public institutions has been made possible.

The new regulation introduced monthly production and consumption offsetting.

The scope of unlicensed power plants has been increased to 5 MW.

The legislative update on August 11, 2022, introduced the following regulations:

The possibility of differentiating consumption zones and production zones has been made possible. This paves the way for consumption points without an established installation area to establish production facilities and offset them anywhere in Turkey, provided technical conditions are met.

Production facilities will be permitted based on their consumption value, but organized industrial zones have been designated as exceptions, allowing production values higher than consumption. This encourages the development of organized industrial facilities.

6. Conclusions

This study comparatively analyzed the renewable energy policies, current installed capacity structures, incentive mechanisms, structural and regional differences, short- and long-term targets, and implementation levels of European Union countries and Turkey. The findings reveal that countries implement significantly different incentive systems based on their levels of economic development, climate conditions, market structures, and regional characteristics.

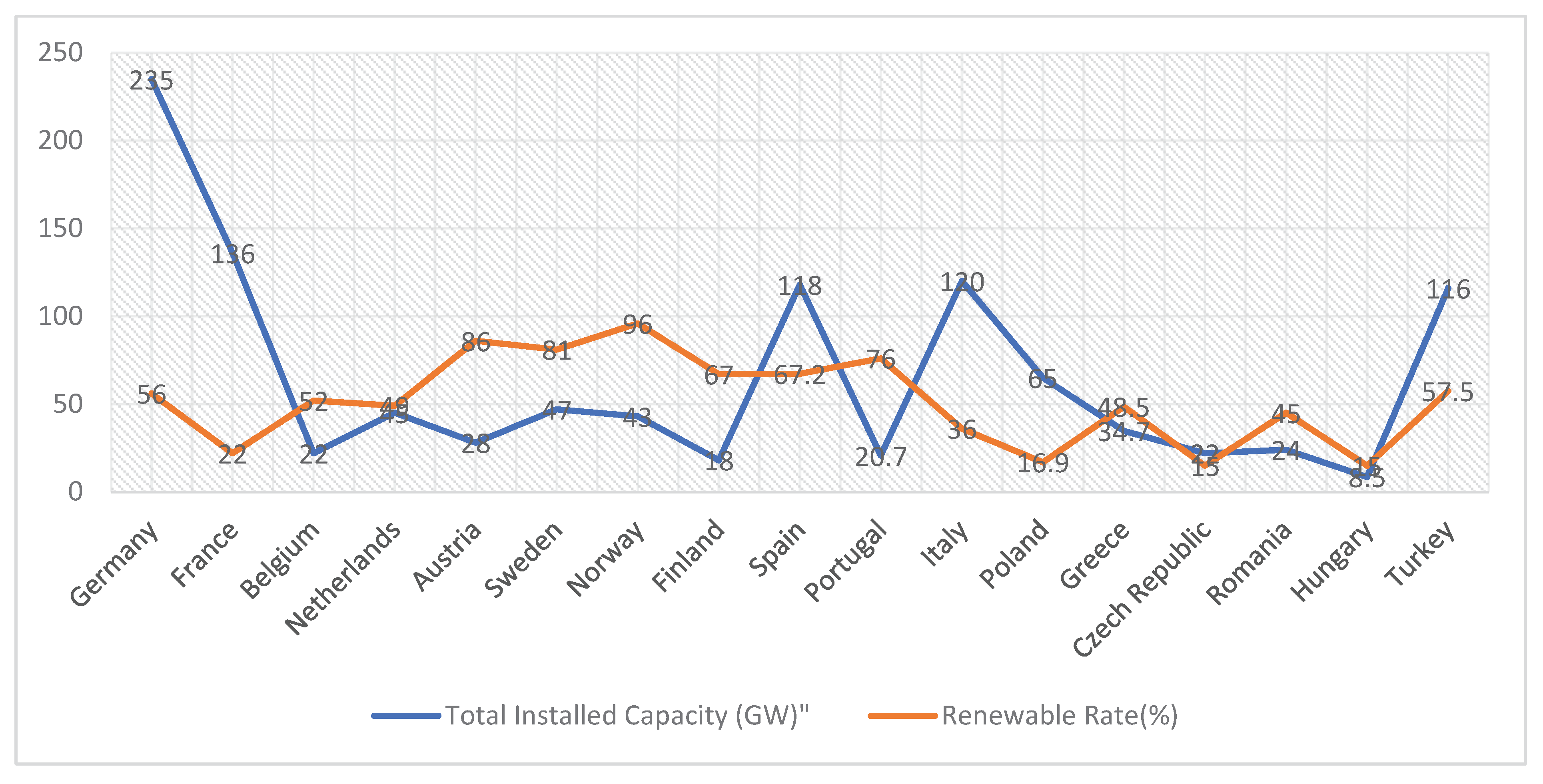

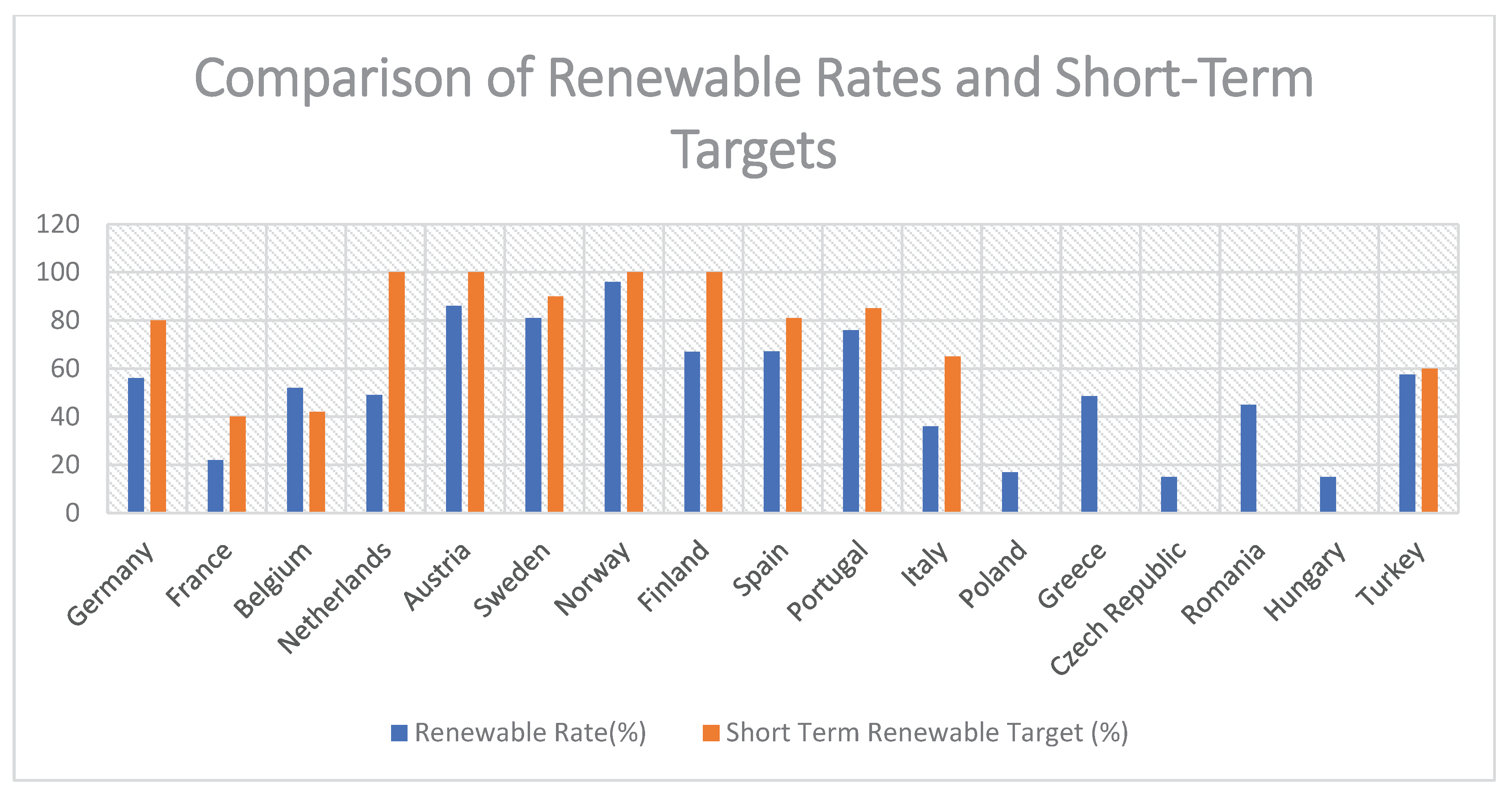

In terms of installed capacity, Germany stands out with 235 GW, while Turkey follows Italy and Spain with 116 GW. Norway has the highest renewable energy usage rate at 96%. Turkey ranks 7th with a target achievement rate of 57.5% and maintains its ranking in terms of incentive effectiveness with a score of 36 out of 50.

While multifaceted incentive mechanisms such as FIT (FIT), green certificates, tax exemptions, and carbon trading systems are widely implemented in EU countries, Turkey primarily implements guaranteed-purchase YEKA (Yeka) projects, tax incentives, and medium-complexity support systems. However, low market predictability and high inflation rates in Turkey negatively impact the effectiveness of incentives. Furthermore, Turkey’s low level of individual net metering implementation emerges as another significant factor limiting renewable energy installation rates. The primary reasons for this include late implementation, low levels of economic development, apartment-type housing density, and limited rooftop availability.

Regionally, Western and Northern European countries have more complex, structured, and effective incentive policies, while Eastern and Southern European countries prefer simpler, more direct, and publicly supported incentive methods. While countries like Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands have achieved high renewable energy penetration through multi-tiered systems, installation rates are quite low in countries like Hungary due to inadequate incentive structures and a lack long-term visions such as the 2030–2050 targets.

While Turkey’s incentive policies are more decisive and comprehensive than those of countries like Poland and Hungary, they exhibit a less integrated and complex structure compared to countries like Germany, France, and the Netherlands. Turkey has focused on large-scale projects in the post-2022 period; This has driven medium-sized investors away from the sector, reducing energy penetration and individual participation.

As part of their long-term goals, most EU countries have adopted a carbon neutrality vision and integrated new incentives, such as green hydrogen production, into their policies. Turkey has similarly incorporated carbon neutrality targets into both its short- and long-term plans.

This comprehensive analysis provides policymakers, energy sector stakeholders, and academia with an important reference for understanding the current situation and making forward-looking strategic decisions. The policy recommendations developed based on the findings provide guidance for making Turkey’s renewable energy policies more sustainable, effective, and inclusive.