Submitted:

23 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Research Instrument

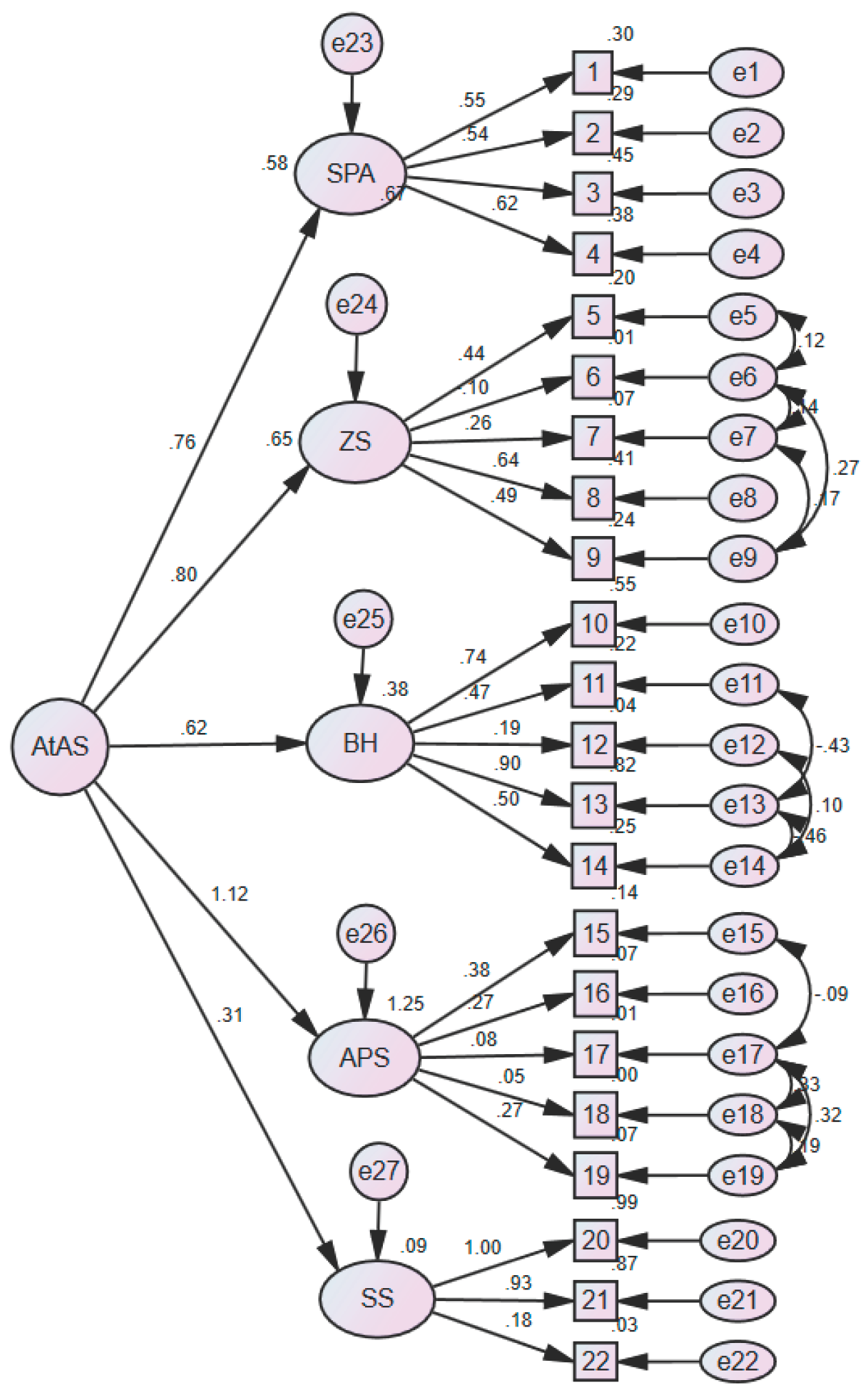

- Adjustment to Aging Scale (AtAS): This Scale (AtAS) was originally developed and psychometrically validated by Sofia von Humboldt et al. in 2014 [23]. AtAS was administered to 1,291 community-dwelling older adults aged 75 to 102 years from both urban and rural areas across four nationalities (Angolan, Brazilian, English, and Portuguese). The AtAS is designed to measure the degree of adjustment to aging and consists of 22 items across five dimensions: Sense of Purpose and Ambition (SPA, 4 items), Zest and Spirituality (ZS, 5 items), Body and Health (BH, 5 items), Aging in Place and Stability (APS, 5 items), and Social Support (SS, 3 items). Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 7 (very important), with higher scores indicating greater adjustment to aging. The internal consistency of the original scale was reported to be 0.89.

- WHO 5 well-being index: This Index is a short, general measure developed by the World Health Organization to assess subjective well-being, focusing exclusively on positive statements [28]. The scale was first validated in Iran by Mortezavi et al. (2013), reporting a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 [29]. The scale consists of five items, each rated on a 6-point Likert scale based on how the respondent felt over the past two weeks. Response options range from “All of the time” (5) to “At no time” (0), with higher scores indicating greater well-being. The total raw score (ranging from 0 to 25) is multiplied by 4 to produce a final score between 0 and 100. A score above 52 is considered to indicate good well-being, whereas a score below 52 may reflect reduced well-being. Additionally, a raw score below 13 (before multiplication) may suggest poor emotional well-being and may warrant further assessment [28].

2.5. Description of the Procedure

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Data Management and Floor/Ceiling Effects

3.2. Descriptive Results

| Variables | Mean (SD) | T/F Statistic | p-value | post hoc Tukey tests | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | R= 0.16- | 0.002* | - | ||

| Gender | Male Female |

110.29 (15.54) 106.57 (15.73) |

t (326)= 2.13 | 0.03* | - |

| Marital Status | Never Married Married Widowed divorced |

102.09 (14.69) 110.74 (15.14) 100.72 (14.93) 108.45 (17.59) |

F (3, 324) = 8.24 |

P<0.001* | 2>3, p<0.05 |

| Education Status | Illiterate Literate (no formal education) Primary Lower Secondary Upper Secondary Diploma University Education |

92.04 (15.75) 109.28 (17.31) 110.97 (17.28) 110.38 (13.84) 106.05 (14.13) 106.47 (15.21) 112.38 (13.95) |

F(6, 321)= 6.66 | P<0.001* | 3>1, p<0.05 4>1, p<0.05 6>1, p<0.05 7>1, p<0.05 |

| Employment Status | Employment Full-Time Employment Part-Time Homemaker Retired Disable/Unable to Work |

114.16 (14.13) 105.47 (13.07) 106.18 (15.97) 110.01 (15.20) 92.80 (26.95) |

F(4, 323)= 3.12 | 0.01* | - |

| Reason for Employment | Financial necessity Habit and leisure Both reasons |

107.41 (14.49) 111.57 (17.36) 109.82 (13.61) |

F(2, 49)= 0.25 | 0.77 | - |

| Economic Status | Very good Good Average Poor Very poor |

124.20 (5.89) 113.74 (14.79) 108.39 (15.36) 99.60 (13.66) 101.88 (18.05) |

F(4, 323)= 8.25 | P<0.001* | 1>4, p<0.05 1>5, p<0.05 2>4, p<0.05 2>5, p<0.05 3>4, p<0.05 |

| Home Ownership | Owned Rented/Mortgaged Child’s Home Relative’s or friend’s Home |

108.82 (15.42) 105.78 (16.53) 116 (12.56) 90 (26.87) |

F(3, 324)= 1.96 | 0.11 | - |

| Living Arrangements | Living alone With spouse only With spouse and unmarried children With spouse and married children Without spouse, with unmarried children Without spouse, with married children With relatives other |

104.22 (16.60) 110.70 (15.40) 110.23 (15.21) 100.16 (10.26) 101.62 (14.41) 92.57 (13.62) 114.25 (13.18) 121.66 (14.97) |

F(7, 320)= 3.88 | P<0.001* | - |

| Area of residence | Region 2 Region 4 Region 5 Region 14 Region 15 |

111.65 (14.49) 107.28 (17.19) 104.52 (15.95) 107.88 (13.57) 111.10 (15.13) |

F(4, 323)= 2.67 | 0.03* | 1>3, p<0.05 |

| general Health Status | Excellent Very good Good Fair poor |

121.18 (8.48) 121 (8.73) 113.69 (12.79) 103.35 (14.96) 90.33 (14.46) |

F(4, 323)= 29.52 | P<0.001* | 1>4, p<0.05 1>5, p<0.05 2>4, p<0.05 2>5, p<0.05 3>4, p<0.05 3>5, p<0.05 4>5, p<0.05 |

| Type of Insurance Coverage | Basic insurance Supplementary insurance Both none |

104 (15.29) 108.90 (16.32) 110.45 (15.05) 106.80 (17.20) |

F(3, 324)= 3.14 | 0.02* | 3>1, p<0.05 |

3.3. Face Validity

3.4. Content Validity

3.5. Construct Validity (Confirmatory Factor Analysis)

| Model | X2/DF | GFI | RMSEA | PCLOSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended value | <3 | ≥0.9 | <0.1 | >0.05 |

| AtAS | 2.499 | 0.86 | 0.06 | 0.000 |

| AtAS (corrected) | 2.06 | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

3.5.1. Convergent Validity and Composite Reliability

| Dimensions of AtAS | SPA | ZS | BH | APS | SS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVE | 0.36 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 0.06 | 0.62 |

| CR | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.71 | 0.19 | 0.79 |

3.5.2. Discriminant Validity

| √AVE | SPA | ZS | BH | APS | SS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPA | 0.60 | - | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.21 |

| ZS | 0.42 | 0.36 | - | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.12 |

| BH | 0.61 | 0.38 | 0.19 | - | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| APS | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.29 | - | 0.19 |

| SS | 0.79 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.19 | - |

3.6. Criterion Validity

3.7. Reliability

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AtAS | Adjustment to Aging Scale |

| CVI | Content Validity Index |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| GFI | Goodness-of-Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| PCLOSE | P-value for Close fit |

Appendix A

Appendix A. Persian Version of the Adjustment to Aging Scale (AtAS)

| خیلی موافقم | موافقم | تاحدودی موافقم | نظری ندارم | تاحدودی مخالفم | مخالفم | خیلی مخالفم | بر اساس موقعیت خود در یک سال گذشته پاسخ دهید | ردیف |

| فعال هستم و در کار مورد علاقه ام فعالیت میکنم | 1 | |||||||

| کنجکاو هستم و به یادگیری علاقه دارم | 2 | |||||||

| خلاق هستم و چیزهای جدیدی درست میکنم | 3 | |||||||

| اثر گذار هستم و برای آینده تلاش میکنم | 4 | |||||||

| خنده رو و شوخ طبع و اهل تفریح هستم | 5 | |||||||

| به دین و معنویت اعتقاد دارم و آدم معنوی هستم | 6 | |||||||

| تغییرات زندگی را میپذیرم | 7 | |||||||

| از سن خود بهترین استفاده را میکنم | 8 | |||||||

| نسبت به آینده احساس آرامش دارم | 9 | |||||||

| سالم هستم و درد یا بیماری ندارم | 10 | |||||||

| بیرون از منزل ورزش میکنم و فعالیت بدنی دارم (پیاده روی و …) | 11 | |||||||

| با اصول خودم زندگی میکنم و مستقل هستم | 12 | |||||||

| به دارو یا درمان خاصی وابستگی ندارم | 13 | |||||||

| از بدن و ظاهر خود راضی هستم | 14 | |||||||

| بیرون از خانه تحرک و فعالیت دارم (خرید و....) | 15 | |||||||

| همسایه های حامی دارم | 16 | |||||||

| آب و هوای محل زندگی ام خوب و سالم است | 17 | |||||||

| بیرون از منزل امنیت دارم | 18 | |||||||

| ثبات و آسایش اقتصادی دارم | 19 | |||||||

| با همسرم/ شریک زندگی ام صمیمی هستم | 20 | |||||||

| همسر/ همراه خوبی دارم | 21 | |||||||

| برای خانواده ام عزیز هستم | 22 |

References

- WHO (WHO). overview of aging paopulation 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/ageing#tab=tab_1.

- Xu, J. A tripartite function of mindfulness in adjustment to aging: Acceptance, integration, and transcendence. The Gerontologist. 2018, 58(6), 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palgi, Y.; Shrira, A.; Neupert, S.D. Views on aging and health: A multidimensional and multitemporal perspective; Oxford University Press US, 2021; pp. 821–824. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Bai, X.; Knapp, M. Multidimensional retirement planning behaviors, retirement confidence, and post-retirement health and well-being among Chinese older adults in Hong Kong. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2022, 17(2), 833–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BaltesPB. Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental psychology. 1987, 23(5), 611. [CrossRef]

- Van Solinge, H. The Oxford Handbook of Retirement (chapter 20: Adjustment to retirement); OUP: USA, 2013; 638p. [Google Scholar]

- Purrington, J. Psychological adjustment to spousal bereavement in older adults: A systematic review. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying. 2023, 88(1), 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroya, K.; Tabuchi, Y.; Kumagai, Y.; Sakamoto, M.; Tajima, T. Factors Contributing to Well-Being in Japanese Community-Dwelling Older Adults Who Experienced Spousal Bereavement. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2024, 17(3), 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Ji, Q.; Ji, P.; Chen, Y.; Song, M.; Ma, J.; et al. The relationship between sleep quality and quality of life in middle-aged and older inpatients with chronic diseases: Mediating role of frailty and moderating role of self-esteem. Geriatric Nursing. 2025, 61, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jangi Jahantigh, L.; Latifi, Z.; Soltanizadeh, M. Effect of self-healing training on death anxiety and sleep quality of older women living in nursing homes. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2022, 17(3), 380–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, R.; Khodaparast, FS. Living arrangements of Iranian older adults and its socio-demographic correlates. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2023, 18(1), 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Mariscal, A.; Corral-Perez, J.; Vazquez-Sanchez, M.A.; Avila-Cabeza-de-Vaca, L.; Costilla, M.; Casals, C. Benefits of an educational intervention on functional capacity in community-dwelling older adults with frailty phenotype: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2025, 162, 104955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirmohammadian, E.; Naeimi, E.; Kazemian, S. Qualitative study of the role of family experiences in the elderly adjustment. journal of Cultural Psychology. 2020, 4(1), 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Von Humboldt, S. Conceptual and methodological issues on the adjustment to aging. International Perspective on Aging (series 15); Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- von Humboldt, S.; Leal, I. Adjustment to aging in late adulthood: A systematic review. International Journal of Gerontology. 2014, 8(3), 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, S.T. Strength and vulnerability integration: A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychological bulletin. 2010, 136(6), 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, H.R. Can a good life be unsatisfying? Within-person dynamics of life satisfaction and psychological well-being in late midlife. Psychological Science. 2019, 30(5), 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklasson, J.; Conradsson, M.; Hörnsten, C.; Nyqvist, F.; Padyab, M.; Nygren, B.; et al. Psychometric properties and feasibility of the Swedish version of the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale. Quality of Life Research. 2015, 24(11), 27952–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.-S.; Hsieh, C.-J.; Tallutondok, E.B.; Shih, Y.-L.; Liu, C.-Y. Development and assessment of the validity and reliability of the short-form life satisfaction index (LSI-SF) among the elderly population. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022, 12(5), 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyas, Z.; Muazzam, A. Development and validation of a general adjustment to aging scale in Pakistan. J Art Soc Sci. 2015, 2(2), 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Taghinezhad, Z.; Eghlima, M.; Arshi, M.; Pourhossein Hendabad, P. Effectiveness of Social Skills Training on Social Adjustment of Elderly People. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2017, 18(3), 230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hajishhvirdi, M.; Khodabakhshi Kolaei, A.; Falsafinejad, MR. The Effectiveness of Mind Games in Improving the Psychological Adjustment in Older Men. Journal of Assessment and Research in Applied Counseling. 2020, 2(3), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Humboldt, S.; Leal, I.; Pimenta, F.; Maroco, J. Assessing adjustment to aging: A validation study for the Adjustment to Aging Scale (AtAS). Social Indicators Research. 2014, 119, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, R.H. Ageing in Nepal. Asia Pacific Population Journal. 2004, 19, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lariscy, J.T.; Tasmim, S.; Collins, S. Racial and ethnic disparities in health. Encyclopedia of gerontology and population aging; Springer, 2022; pp. 4128–4136. [Google Scholar]

- Madarasmi, S.; Trinh, N.-H.; Ahmed, I. Culture and aging: The role of culture, race, and ethnicity. Mental Health in Older People Across Cultures 2024, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, R.; Zanjari, N. The inequality of development in the 22 districts of Tehran metropolis. Social Welfare Quarterly. 2017, 17(66), 149–184. [Google Scholar]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 2015, 84(3), 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, F.; Mousavi, S.-A.; Chaman, R.; Khosravi, A. Validation of the World Health Organization-5 Well-Being Index; Assessment of Maternal Well-Being and its Associated Factors. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2015, 26(1). [Google Scholar]

- Severinsson, E. Evaluation of the Manchester clinical supervision scale: Norwegian and Swedish versions. Journal of Nursing Management. 2012, 20(1), 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waltz, C.F.; Bausell, BR. Nursing research: Design statistics and computer analysis; Davis Fa, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Zadworna, M. Pathways to healthy aging–exploring the determinants of self-rated health in older adults. Acta Psychologica. 2022, 228, 103651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Cao, J.; Tang, K.; Cheng, S.; Ren, Z.; Li, S.; et al. Self-rated health, interviewer-rated health, and objective health, their changes and trajectories over time, and the risk of mortality in Chinese adults. Frontiers in public health. 2023, 11, 1137527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achdut, N.; Sarid, O. Socio-economic status, self-rated health and mental health: The mediation effect of social participation on early-late midlife and older adults. Israel journal of health policy research. 2020, 9(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhou, A.; Tang, P.; Ma, X. Socioeconomic status moderate the relationship between mental health literacy, social participation, and active aging among Chinese older adults: Evidence from a moderated network analysis. BMC Public Health. 2025, 25(1), 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belachew, A.; Cherbuin, N.; Bagheri, N.; Burns, R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the socioeconomic, lifestyle, and environmental factors associated with healthy ageing in low and lower-middle-income countries. Journal of Population Ageing. 2024, 17(2), 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsson, B.; Molarius, A. Self-rated health and associated factors among the oldest-old: Results from a cross-sectional study in Sweden. Archives of Public Health. 2020, 78(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montross, L.P.; Depp, C.; Daly, J.; Reichstadt, J.; Golshan, S.; Moore, D.; et al. Correlates of self-rated successful aging among community-dwelling older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006, 14(1), 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velaithan, V.; Tan, M.-M.; Yu, T.-F.; Liem, A.; Teh, P.-L.; Su, TT. The association of self-perception of aging and quality of life in older adults: A systematic review. The Gerontologist. 2024, 64(4), gnad041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, S. Gender differences in the subjective well-being of older adult learners in China. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 1043420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafetz, JS. The varieties of gender theory in sociology. Handbook of the sociology of gender; Springer, 2006; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Vega, M.; Esparza-Del Villar, O.A.; Carrillo-Saucedo, I.C.; Montañez-Alvarado, P. The possible protective effect of marital status in quality of life among elders in a US-Mexico border city. Community mental health journal. 2018, 54(4), 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, Z.K.; Yuen, J.J.X.; Ashari, A.; Ibrahim Bahemia, F.; Low, Y.X.; Nik Mustapha, N.M.; et al. Forward-backward translation, content validity, face validity, construct validity, criterion validity, test-retest reliability, and internal consistency of a questionnaire on patient acceptance of orthodontic retainer. PLoS ONE. 2025, 20(1), e0314853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.; Beck, C.; Owen, S. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in Nursing ana Health. 2007, 30(4), 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, CT. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Research in nursing & health 2006, 29(5), 489–497. [Google Scholar]

- Zamanzadeh, V.; Ghahramanian, A.; Rassouli, M.; Abbaszadeh, A.; Alavi-Majd, H.; Nikanfar, A.-R. Design and implementation content validity study: Development of an instrument for measuring patient-centered communication. Journal of caring sciences 2015, 4(2), 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015; 462p. [Google Scholar]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000, 25(24), 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, V.D.; Rojjanasrirat, W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2011, 17(2), 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, S.; Royse, C.F.; Terkawi, AS. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi journal of anaesthesia. 2017, 11 (Suppl 1), S80–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barišić, M.; Mudri, Ž.; Farčić, N.; Čebohin, M.; Degmečić, D.; Barać, I. Subjective well-being and successful ageing of older adults in Eastern Croatia—Slavonia: Exploring individual and contextual predictors. Sustainability. 2024, 16(17), 7808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale development: Theory and applications; Sage publications, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R.; Cairney, J. Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use; Oxford university press, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean (SD) | 69.42 (±6.8) |

| Gender | Male Female |

144 (43.9%) 184 (%56.1) |

| Marital Status | Never Married Married Widowed divorced |

11 (3.4%) 288 (69.5%) 69 (21%) 20 (6.1%) |

| Education Status | Illiterate Literate (no formal education) Primary Lower Secondary Upper Secondary Diploma University Education |

24 (7.3%) 7 (2.1%) 36 (11%) 26 (7.9%) 17 (5.2%) 110 (33.5%) 108 (33%) |

| Employment Status | Employment Full-Time Employment Part-Time Homemaker Retired Disable/Unable to Work |

18 (5.5) 21 (6.4) 127 (38.7) 157 (47.9) 5 (1.5) |

| Reason for Employment | Financial necessity Habit and leisure Both reasons |

17 (32.7) 7 (13.5) 28 (53.8) |

| Economic Status | Very good Good Average Poor Very poor |

5 (1.5) 70 (21.3) 190 (57.9) 46 (14) 17 (5.2) |

| Home Ownership | Owned Rented/Mortgaged Child’s Home Relative’s or friend’s Home |

255 (77.7) 66 (20.1) 5 (1.5) 2 (0.6) |

| Living Arrangements | Living alone With spouse only With spouse and unmarried children With spouse and married children Without spouse, with unmarried children Without spouse, with married children With relatives other |

49 (14.9) 102 (31.1) 118 (36) 6 (1.8) 35 (10.7) 7 (2.1) 8 (2.4) 3 (0.9) |

| general Health Status | Excellent Very good Good Fair poor |

22 (6.7) 14 (4.3) 126 (38.4) 139 (42.4) 27 (8.2) |

| Type of Insurance Coverage | Basic insurance Supplementary insurance Both none |

80 (24.4) 60 (18.3) 153 (46.6) 35 (10.7) |

| Dimension | Score range | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPA | 4-28 | 18.70 | 5.21 |

| ZS | 5-35 | 26.32 | 4.50 |

| BH | 5-35 | 24.42 | 5.71 |

| APS | 5-37 | 22.90 | 5.05 |

| SS | 3-21 | 15.84 | 4.11 |

| Total | 22-154 | 108.27 | 15.77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).