Submitted:

24 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

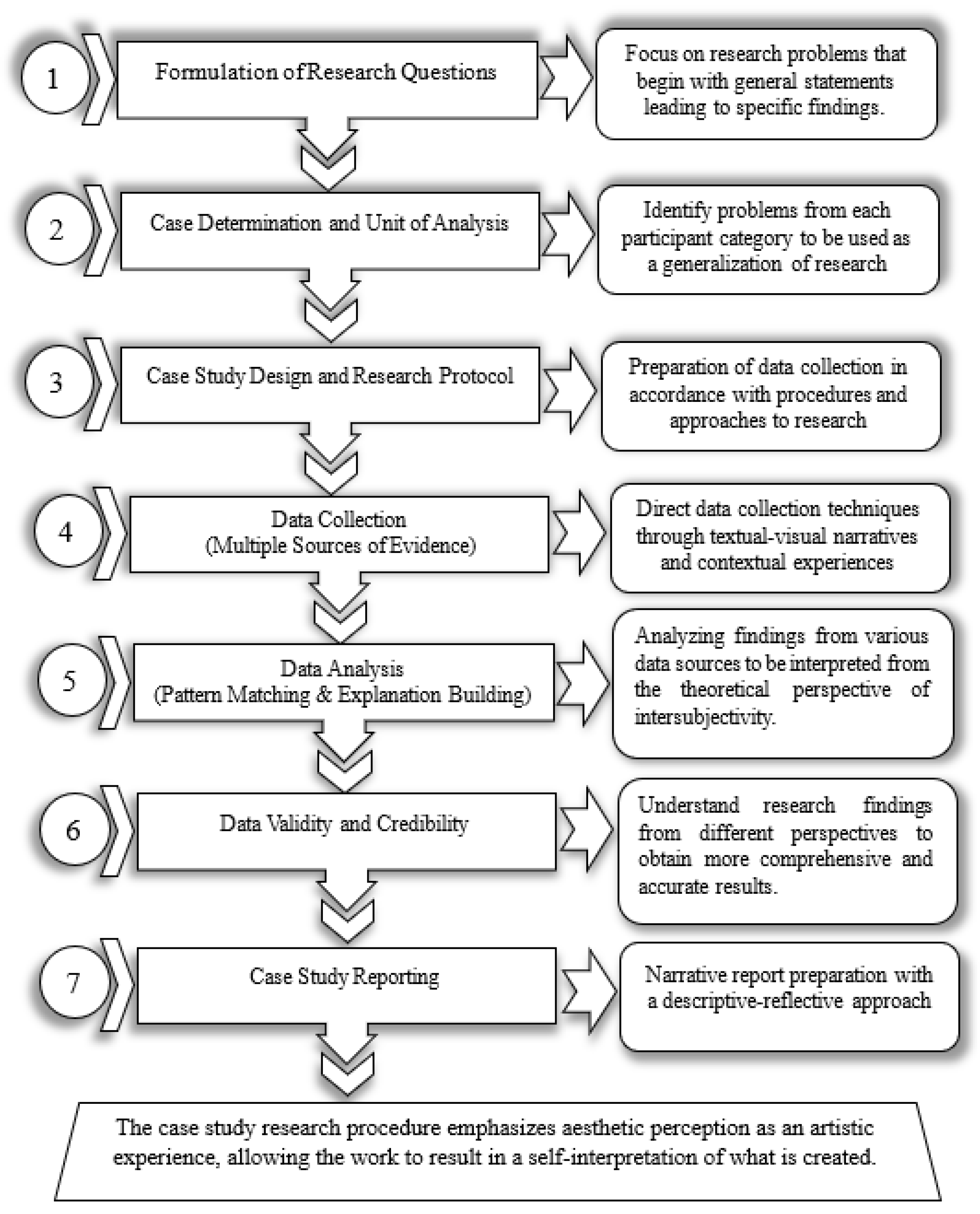

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Perception of Low Vision Beneficiaries Towards Clay Materials

“I got to know clay materials during school learning, and together with friends were introduced through hand touch to identify the clay. I also played with friends at home when making a well at home, and I wanted to try making bowls, plates, and other eating utensils, which I hope can become objects that can be used for everyday needs”.

“When I was taking lessons at SDLB-A, the teacher asked me to hold clay by feeling and squeezing it. The teacher asked me to form various shapes from my fists to produce shapes like small balls, plates, and asked me to combine the shapes. What I remember at that time was making fruit shapes and people shapes. Back then, my friends at SDLB-A were very happy and enthusiastic about the lesson. It is possible that if there are more activities like that, I will feel challenged to create works of art using clay that suit my wishes, namely wanting to make animal statues”.

“I used to do various art activities when I had normal vision. When I was a child, until I was an adult, I could understand how to create art, especially using clay, from kindergarten to high school. I have various experiences in creating art with clay media, such as making statues, pottery, and playing with clay. I often got that knowledge from junior high and high school in the Arts and Crafts (SBK) subject. In the past, during SBK learning, my teacher assigned me to make a face sculpture artwork and also told me to make pottery with the motif.

3.2. The Process of Low Vision Beneficiary Artistic Experience in Creating Art with Clay Media

3.3. The Results of Creating Art with Clay Media as an Artistic Experience for Low Vision Beneficiaries

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Papa, M.; Papa, A. The transformative capacity of communication for social change and peacebuilding. In The Routledge Handbook of Conflict and Peace Communication, 1st Ed; Routledge: New York, 2024; pp. 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M. A. Art as a Mirror of Cultural Values: A Philosophical Exploration of Aesthetic Expressions. Cultura: Int. J. of Phil. of Culture and Axiology 2025, 22, 245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Fajrie, N.; Purbasari, I.; Bamiro, N. B.; Evans, D. G. Does art education matter in inclusiveness for learners with disabilities? A systematic review. Int. J. of Learning, Teaching and Edu. Research 2024, 23, 96–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B. M.; Smart, E.; King, G.; Curran, C. J.; Kingsnorth, S. Performance and visual arts-based programs for children with disabilities: A scoping review focusing on psychosocial outcomes. Disability and rehabilitation 2020, 42, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d'Evie, F.; Kleege, G. The gravity, the levity: Let us speak of tactile encounters. Disability Studies Quarterly 2018, 38, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, P. Towards a holistic paradigm of art education art education: Mind, body, spirit. Visual arts research 2006, pp. 8–15.

- Phutane, M.; Wright, J.; Castro, B. V.; Shi, L.; Stern, S. R.; Lawson, H. M.; Azenkot, S. Tactile materials in practice: Understanding the experiences of teachers of the visually impaired. ACM Trans. on Access. Comp. (TACCESS) 2022, 15, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, A. What My Students Taught Me about Disability. Thresholds in Edu. 2023, 46, 209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, J. K.; Hinz, L. D.; Lusebrink, V. B. Clay art therapy on emotion regulation: research, theoretical underpinnings, and treatment mechanisms. In The neuroscience of depression 2021, pp. 431–442. Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wei, P. The Beauty of Clay: Exploring contemporary Ceramic Art as an Aesthetic Medium in Education. Comunicar: Revista Científica de Comunicación y Edu. 2024, (78), 67-81.

- Yusuf, M.; Yeager, J. L. The implementation of inclusive education for students with special needs in Indonesia. Excellence in Higher Edu. 2011, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rante, N, S. V.; Wijaya, H.; Tulak, H. Far from expectation: A systematic literature review of inclusive education in Indonesia. Uni. J. of Edu. Research 2020, 8, 6340–6350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höger, B.; Meier, S. Exploring Marginalized Perspectives: Participatory Research in Physical Education with Students with Blindness and Visual Impairment. J. of Teaching in Physical Edu. 2025, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočnik, R.; Zavšek, K.; Vidrih, A. Visual Art Activities as a Means of Realizing Aspects of Empowerment for Blind and Visually Impaired Young People. European J. of Edu. Research 2025, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bux, D. B.; van Schalkwyk, I. Creative arts interventions to enhance adolescent well-being in low-income communities: An integrative literature review. J. of Child & Adolescent Mental Health 2022, 34(1-3), 1-29. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E. E.; Bergelson, E. Making sense of sensory language: Acquisition of sensory knowledge by individuals with congenital sensory impairments. Neuropsychologia 2022, 174, 108320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage publications: London, 2017.

- Massaro, M.; Dumay, J.; Bagnoli, C. Transparency and the rhetorical use of citations to Robert Yin in case study research. Med. Accoun. Research 2019, 27, 44–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, B. P.; Silverstein, S. M.; Papathomas, T. V.; Krekelberg, B. Correcting visual acuity beyond 20/20 improves contour element detection and integration: A cautionary tale for studies of special populations. Plos one 2024, 19, e0310678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. A.; Larkin, M.; Flowers, P. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Sage Publication: London 2021, p. 100.

- Brady, E.; Brook, I.; Prior, J. Between nature and culture: The aesthetics of modified environments. Rowman & Littlefield: Maryland, USA, 2018.

- Bar-On, T. A meeting with clay: Individual narratives, self-reflection, and action. Psy. of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 2017, 1, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, N.; Vermol, V. V.; Anwar, R.; Kaspin, S. Visual Art Accessibility and Art Experience for the Blind and Visually Impaired. The Int. J. of Design in Society 2024, 19, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobnick, J.; Fisher, J. Introduction: sensory aesthetics. The Senses and Society 2012, 7, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagtvedt, H. A brand (new) experience: Art, aesthetics, and sensory effects. J. of the Academy of Marketing Science 2022, 50, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, G. M. Neurocognitive rehabilitation: skills or strategies? The American J. of Occup. Therapy 2018, 72, p1–p7206150010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsen, N. K.; Gjærum, R. The Aesthetic Model of Disability. In: Janse Van Vuuren P, Rasmussen BK, Khala. Theatre and Democracy: Building Democracy in Post-war and Post-democratic Contexts. Cappelen Damm Akademisk 2021, p. 193-215.

- Chilton, G. Art therapy and flow: A review of the literature and applications. Art Therapy 2013, 30, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, E. R. Liberation psychology, creativity, and arts-based activism and artivism: Culturally meaningful methods connecting personal development and social change. In L. Comas-Díaz & E. Torres Rivera (Eds.), Liberation psychology: Theory, method, practice, and social justice, American Psychological Association: Washington DC 2020, pp. 247–264. [CrossRef]

- Fajrie, N.; Purbasari, I.; Bamiro, N. The perceptual ability of visual impaired children in the experience of making clay media artworks. Arts Educa 2024, 40, 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J. D. A study of multi-sensory experience and color recognition in visual arts appreciation of people with visual impairment. Electronics 2021, 10, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Respondent ID | Age | Gender | Level of vision | Onset of impairment | Prior artistic Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R01 | 22 | Female | Can perceive light and shadow only | Congenital | None |

| R02 | 35 | Male | Can distinguish large shapes and colors | Acquired (at age 18) | Some (school crafts) |

| R03 | 31 | Female | Total blindness | Congenital | Some (music) |

| R04 | 19 | Male | Can perceive light and motion | Congenital | None |

| R05 | 32 | Female | Total blindness | Acquired (at age 25) | None |

| R06 | 28 | Female | Can distinguish large shapes | Congenital | Extensive (hobbyist weaver) |

| R07 | 31 | Male | Can perceive strong colors | Acquired (at age 12) | None |

| R08 | 38 | Female | Total blindness | Congenital | Some (school crafts) |

| R09 | 25 | Male | Can perceive light and shadow only | Congenital | None |

| R10 | 39 | Female | Total blindness | Acquired (at age 30) | None |

| R11 | 21 | Male | Can distinguish large shapes and colors | Congenital | Some (drawing) |

| R12 | 25 | Male | Can perceive motion and large shapes | Acquired (at age 5) | Extensive (wood carving) |

| R13 | 33 | Male | Total blindness | Congenital | None |

| R14 | 29 | Female | Can perceive light and shadow only | Acquired (at age 22) | None |

| R15 | 33 | Female | Total blindness | Congenital | Some (music) |

| No. | Documentation of artworks | Identity of artwork | Analysis of the work |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Title of Work “Frog”

|

The shape of the object produced using a pinch massage technique by forming an animal in a symmetrical position. The addition of objects is used to produce components of the shape on each side of the object |

| 2 |  |

Title of Work: “Ashtray of Love”

|

Applying subtractive techniques to form depressions in clay materials in an effort to produce a central indentation in the artwork |

| 3 |  |

Title of Work: “Kura-Kura”

|

The creation of the work was carried out using the addition of clay materials with a plate technique and elements of cross or zig-zag lines as texture accents on the artwork |

| 4 |  |

Title of Work “Small Jug”

|

Forming clay material using a wooden rod construction inside using a twisting technique |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).