1. Introduction

As shown in WHO reports, over a billion people around the world, that is 15% of the population, are currently affected by some type of disability. This number is growing rapidly due to the ageing population, the spread of chronic diseases, and complications caused by the Covid-19 pandemic [

1].

The convention on the rights of people with disabilities [

2], adopted in 2006 by the United Nations and ratified by all the member states of the European Union, ensures full integration of this group of people. Full inclusion of people with disabilities involves increasing their activity in the public sphere, including improvements in accessibility to various forms of spending leisure time. Accessible tourism is increasing in popularity, with an ever-growing number of attractions, hotels and restaurants declaring that they are open for people with disabilities. According to the definition of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), “accessible tourism is a form of tourism that involves collaborative processes between stakeholders that enables people with access requirements, including mobility, vision, hearing and cognitive dimensions of access, to function independently and with equity and dignity through the delivery of universally designed tourism products, services and environments. This definition adopts a whole of life approach where people through their lifespan benefit from accessible tourism provision. These include people with permanent and temporary disabilities, seniors, obese, families with young children and those working in safer and more socially sustainably designed environments” [

3].

One of the key concepts in the approach to accessible tourism is the accessibility chain, defined as a series of transactions based on the supply of products, services and tourist experiences required by the accessible tourism market [

4,

5,

6].

According to the proposal of the UNWTO, this chain encompasses the urban environment, recreational activities and excursions [

7]. In this context, elements of natural and cultural heritage are key attractions in the tourist industry, in which accessibility must be a basic attribute [

2].

The aim of the paper is to assess the accessibility for people with disabilities of flagship cultural attractions, that is museums located in Krakow, a city with a rich historical heritage entered in 1978 onto the first UNESCO World Cultural and Natural Heritage List. Currently, Krakow is the most recognised tourist brand in Poland, with visitor numbers exceeding 14 million in 2019 [

8]. In 2010, Krakow was distinguished in the first competition organised by the European Union for cities accessible for people with disabilities and older people – the

Access City Award. The city earned this title thanks to efforts which aimed to increase the accessibility of the public space in very difficult surroundings characterised by inaccessible infrastructure. This was achieved thanks to particular attention being paid to providing access to historical sites and museums [

9].

2. Literature review

There is a link between inclusive tourism and social and economic development [

10], and many authors consider that this type of tourism can bring additional social and economic benefits [

11]. Some are of the opinion that accessible tourism should be analysed across a broad spectrum, as it may also relate to other groups of people with special needs (e.g. older people, pregnant women and people travelling with small children) [

12].

A review of the literature related to tourism for people with disabilities points to the growing popularity of this issue [

4], but despite the multitude of publications and the variety of topics, there are few papers that address accessible tourism and people with disabilities comprehensively. A great deal of attention is dedicated in the literature to understanding the specific requirements of people with disabilities. Private and societal attitudes towards disability are described by Darcy and Daruwall [

13]. In their research, they addressed the issue of how the needs of people with disabilities are understood by abled people. On the basis of a literature review, they pointed to key differences between the stereotypical understanding of the needs of people with disabilities and their actual needs [

13].

Research into accessible tourism also involves various interrelated aspects connected to travelling, part of which is related to transport [

14], and the availability of accommodation [

15,

16] and tourist attractions [

17,

18]. Descriptions are provided of the accessibility of tourist attractions on popular tourist routes around Poland [

19] and in historical cities [

20].

The accessibility of tourist sites and attractions in Spain are presented in works by Rucci and Porto [

21] and Santana et al. [

22], while Espinosa and Bonmatí developed a guide to the accessibility of museums and other sites on the UNESCO world heritage list [

5]. In Poland, analysis was conducted of the accessibility of tourist infrastructure for people with disabilities [

23], as well as of sites and tourist offers in Krakow [

24].

Tourism for people with disabilities is a developing segment of the market and brings with it at least two benefits. On the one hand it leads to social inclusion, while on the other in increases the competitiveness of tourist destinations and brings good financial results for the tourist sector [

25,

26,

27,

28].

A very important feature of people with disabilities is also the fact that they travel during the low season, with at least one companion, and are willing to incur significant travel-related expenses [

29]. One example of analysis of local tourist offer accessibility for people with disabilities is a paper on the accessibility of tourist offers on the Istria peninsula in Croatia [

30].

The Covid-19 pandemic showed that new technologies could be used to effectively increase the accessibility of tourist attractions, especially in museums for people with cognitive or sensory disabilities. Smartphones with audio guides, the possibility to directly translate texts into sign language and online communication tools are just a few examples of the use of technology to increase accessibility [

31]. These solutions were above all used in museums, which due to the restrictions in place during the pandemic were mostly closed [

32,

33]. However, as shown in research conducted into Polish museums by Gaweł during the pandemic, despite the wealth of digital offers provided by Polish museums, visitors prefer a return to the ‘real museum’. Although numerous technological solutions that were not in use earlier became a permanent part of museums’ activities, the reaction of visitors after the lockdown was clear – they want to enjoy traditional forms of participating in culture, and most of all value the possibility to have personal contact with original artworks in museum galleries [

34].

3. Museums and cultural attractions in Krakow and their use (visitor numbers)

Krakow is perceived as the most recognised Polish tourist destination, a city of culture and art like Florence or Venice. However, in the Fainstein and Judd classification, it is considered a tourist-historic city whose principal resource is historical and cultural heritage [

35,

36]. This perception of Krakow is also reflected in its entry onto the UNESCO List of World Cultural and Natural Heritage, as well as the selection of Krakow as the European Capital of Culture in the year 2000. It is worth adding that Krakow has also been distinguished as the UNESCO City of Literature and the European Capital of Gastronomy (in 2019).

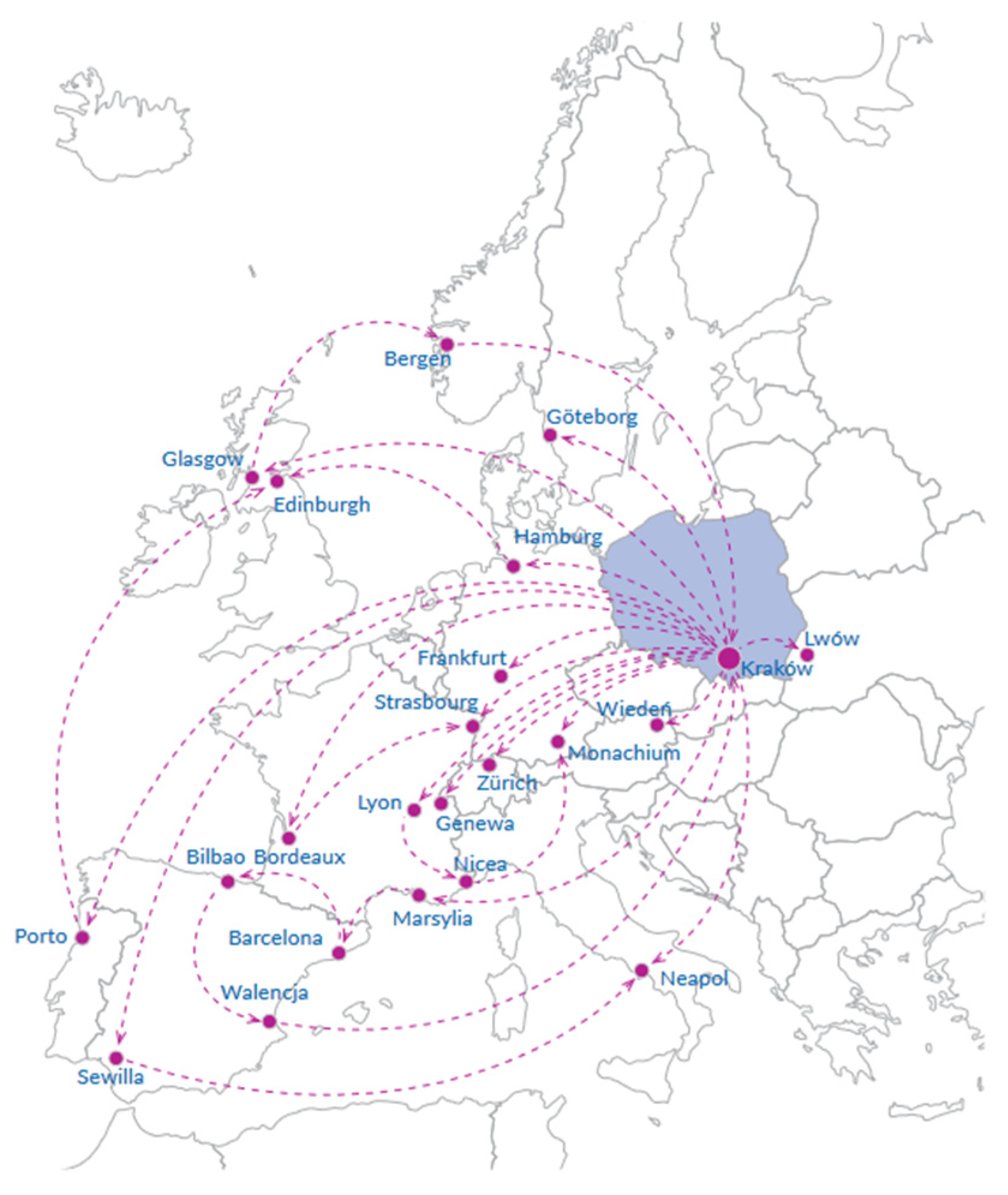

Krakow cooperates with other European cities of similar cultural heritage potential, such as Barcelona, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Nice, Strasbourg and Zurich (

Figure 1) [

37]. It occupies a very high position globally and has a wealth of activity that provides a high quality of life. To the above list, we can also add other cities in Central Europe with a character similar to that of Krakow and with excellent tourist functions, such as Prague, Bratislava and Budapest [

38].

At the beginning of the 21st century, Krakow became an important centre for tourism of international standing. Its wealth and variety of cultural attractions, its potential as a centre for academia, its broad offer of cultural events and well-developed tourist infrastructure are all factors that shape its competitive advantage on the international tourist market [

39].

Krakow has one of the most impressive examples of urban architecture in Central Europe, with more than five thousand historical sites. The most attractive tourist district in Krakow is the Old Town, with the main Market Square at its centre – the largest square of its type in Europe – which together with the characteristic buildings that surround it creates one of the most recognisable urban cityscapes in Poland.

Krakow is one of the largest centres of culture in Poland and Central Europe. It is also an important museum centre [

40]. Various types of museums and collections can be found here: archaeological, historical, artistic, biographical, natural, technical, literary and specialist. In 2021, there were 51 museums and museum branches in Krakow which were among the most highly frequented museums in Poland. In 2022, the Royal castle with its State Art Collection was visited by 1,785,000 people, while 1.4 million people visited the National Museum in Krakow, and 888,000 visited the Museum of Krakow. These are the flagship tourist attractions of the city [

41]. It is worth noting that Krakow is continually expanding and developing its museum offer. This is important, as one of the greatest magnets drawing tourists to Krakow is its cultural heritage, and museums are the principal component of this heritage [

42].

4. Materials and Methods

Research aim

The objective of the research is to assess the accessibility of museums in Krakow for people with disabilities. The research aims to show to what degree museums are adapted to receiving visitors with limited mobility, with sight and hearing impairments, people with cognitive disabilities, as well as seniors, families with small children, pregnant women and people with dietary restrictions. The research should also provide an answer to the question of what percentage of the total number of museum visitors are people with particular needs, and how well museum staff are prepared to receive such people. Another aim is to assess the level of access to both digital and analogue information regarding amenities for visitors, as well as the possibility to make use of virtual tours of the museums’ collections.

Research questions

For which groups of people with special needs are Krakow museums prepared?

Are museum premises adapted for wheelchair users?

What equipment improving accessibility for people with particular needs is available in the museums?

Which groups of people with particular needs visit Krakow museums?

Do the museums employ people trained in how to provide assistance to people with particular needs?

Do the museums provide sufficient information on the accessibility of their premises for people with particular needs?

Do the museums’ websites fulfil the requirements of digital accessibility for people with disabilities?

Do the museums offer virtual tours?

5. Results

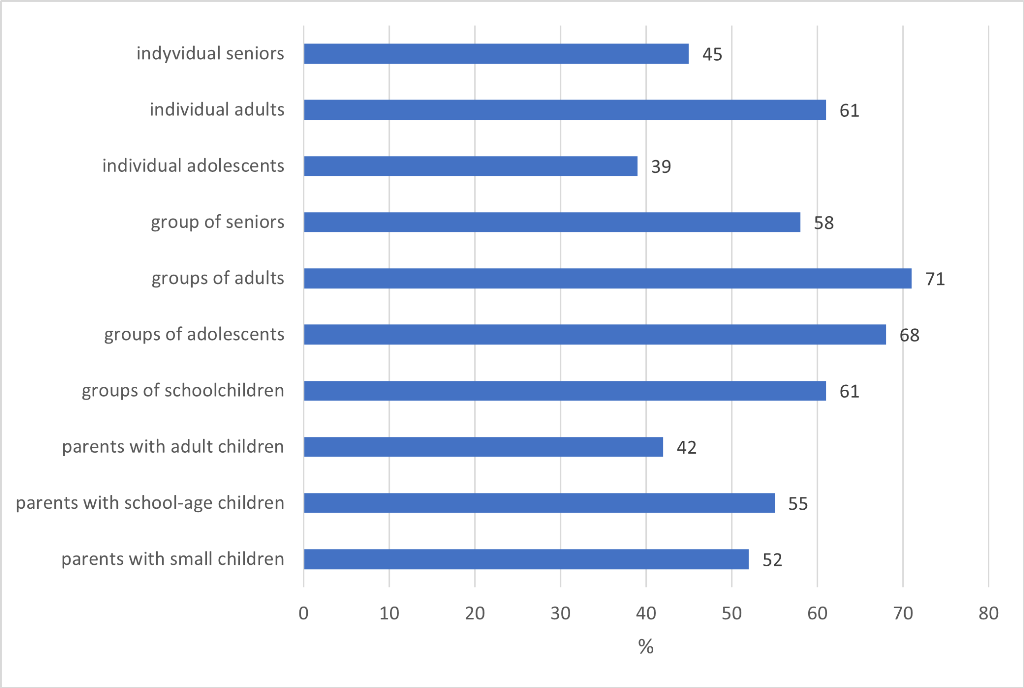

Analysis of the questionnaires provided answers to the previously formulated research questions. The first related to identifying the groups of people with disabilities for whom Krakow museums are accessible. As shown in

Figure 2, Krakow museums are relatively the best prepared for receiving people with physical disabilities, as 87% of the museums declared they were accessible to this group of people. A high percentage of museums were accessible for seniors (80%). The museums are less well adapted to the needs of people with sight impairments and blind people (74%), and those of people with hearing impairments and deaf people (73%). A similar percentage (71%) were accessible to families with prams and children. The lowest number of museums declared that they were accessible to pregnant women (58%).

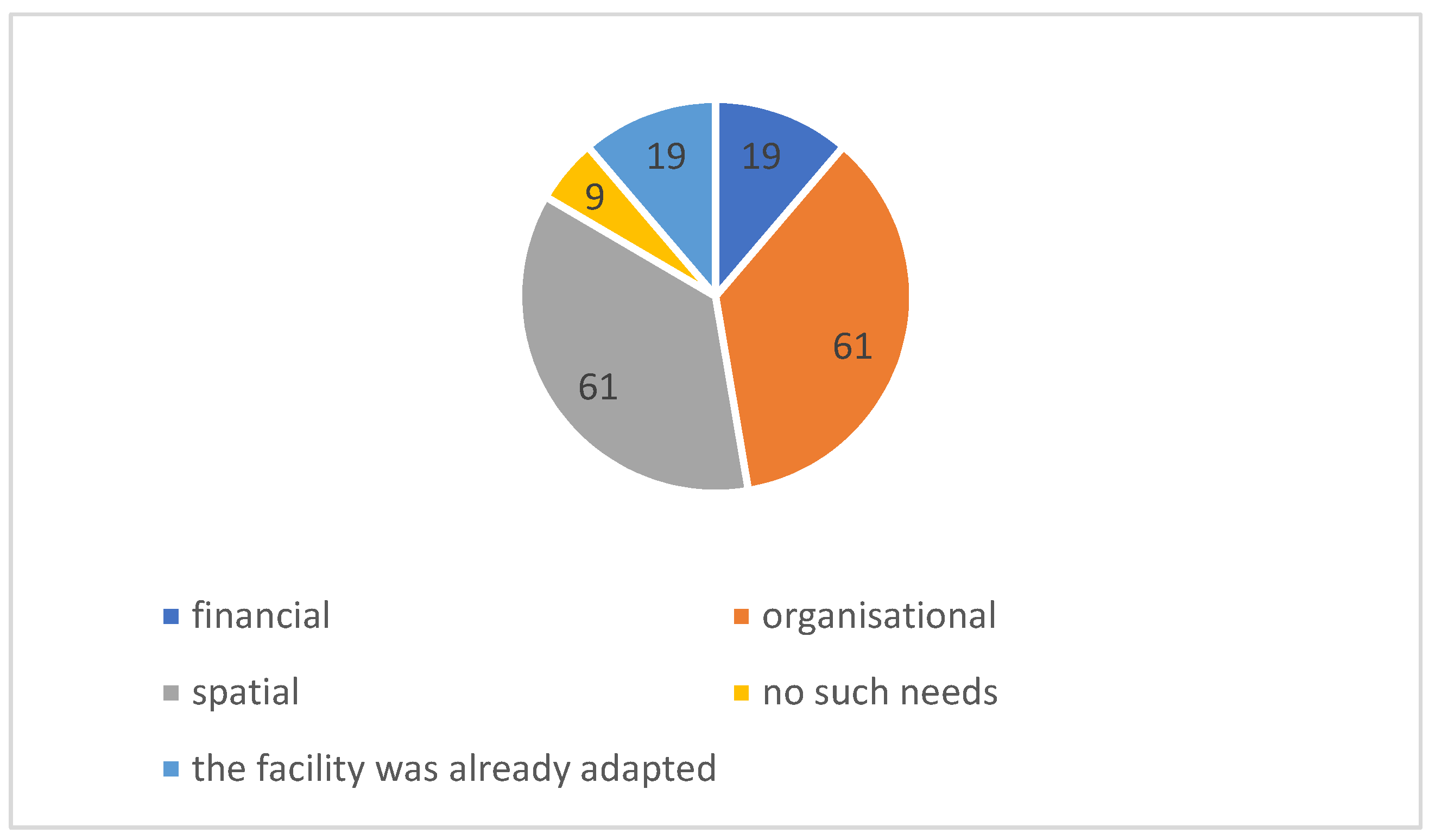

In terms of the answers to question 2, as to whether museum premises were adapted for wheelchair users, the responses indicated that this was a considerable spatial challenge (sometimes due to the historical nature of the museum’s architecture), as well as an organisational and financial challenge, with only 9% of the museums reporting such needs (

Figure 3).

A separate problem is access for people with disabilities to dedicated parking spaces, with only 52% of museums providing such access combined with entry to the museum via kerb-free pavements and ramps or inclines. Adapting premises for wheelchair users required special modifications to buildings at a later date (50% of answers). The majority of museum managers consider that not adapting premises to the needs of wheelchair users is a form of discrimination (81%), with only 19% of the opposite opinion. In general, it was not confirmed by the managers of museums located in historical buildings, the adaptation of which to the needs of people with physical disabilities was limited or impossible.

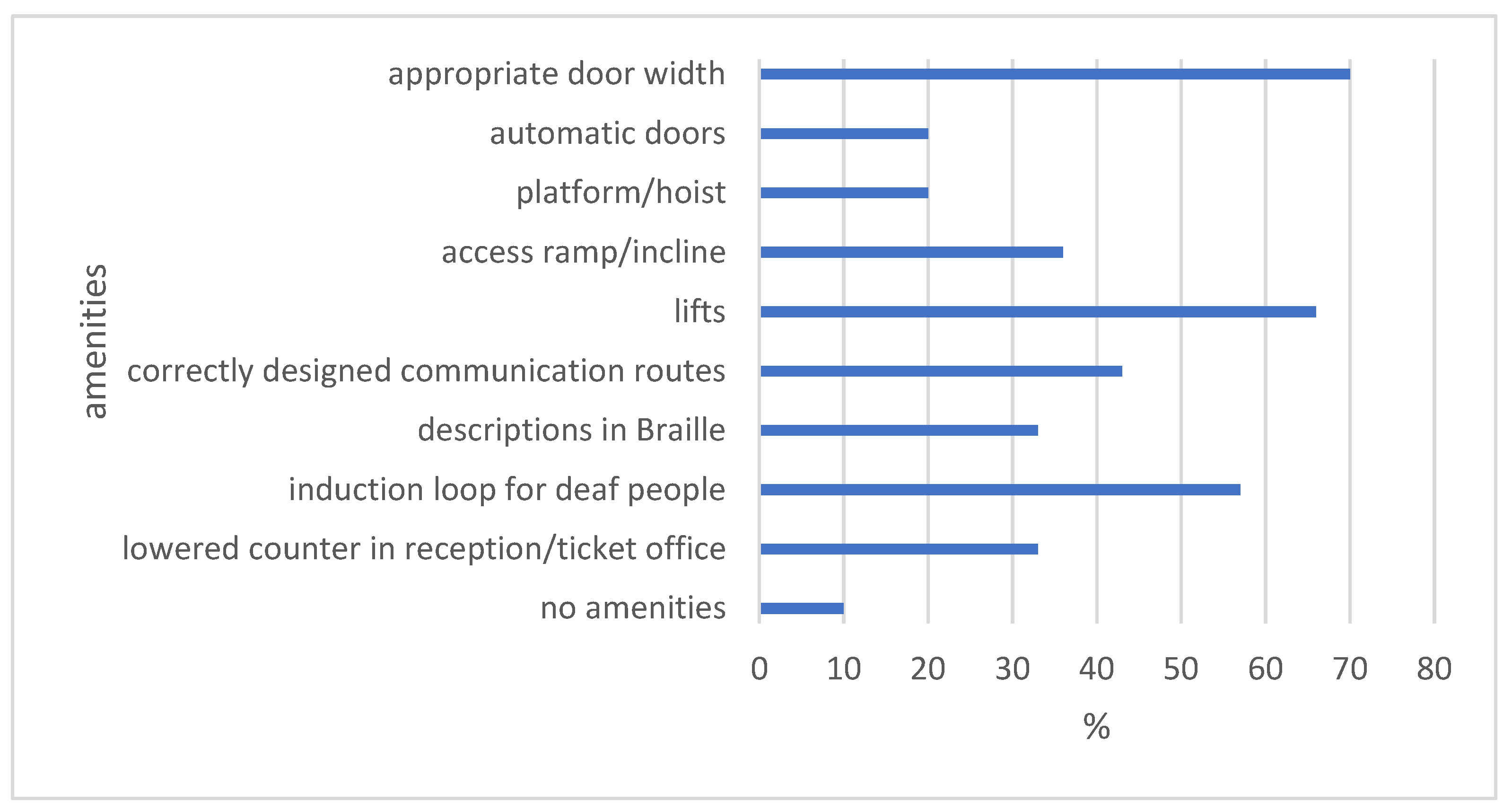

In answer to question 3: ‘What equipment improving accessibility for people with particular needs is available in the museums?’, the responses indicated the appropriate width of museum doors (70%), and the provision of lifts (66%), as well as correctly designed communication routes within the premises (43%). In the majority of the museums, an induction loop has been installed for deaf people (57%). One in three museums had amenities for blind people in the form of descriptions in Braille, as well as inclines and access ramps for people with limited physical ability (36%), lowered counters in reception/ticket offices (33%), platforms/hoists (20%), and automatic doors (20%). Only 10% of the museums did not have any of these amenities (

Figure 4).

It is worth drawing attention to the high degree of adaptation of toilet facilities for the needs of people with disabilities, with as many as 87% of museums declaring that their bathrooms met such standards.

Improving accessibility for people with particular needs is possible thanks to the presence of technical solutions in the museums, as illustrated in

Table 1. The communication routes, lifts and toilets, the flat surfaces and the lack of doorsteps make the majority of Krakow museums accessible for wheelchair users and those with children’s prams. Half of the museums had the appropriate pictograms and warning signs, while one in four had descriptions in Braille. Audio signals for blind people were only found in four museums. The majority of the museums (97%) have public spaces that are adapted for joint use by both people with particular needs and those without.

In answer to the question about which groups of people with particular needs or disabilities visit Krakow museums, it was indicated that all of the groups analysed are represented to differing degrees (

Table 2). 81% of museums confirmed the presence of physically disabled tourists, while 78% reported visits by seniors. The majority of museums (71%) reported the presence of people with sight and hearing impairments, with a lower percentage confirming that of small children (42%) and people with dietary restrictions.

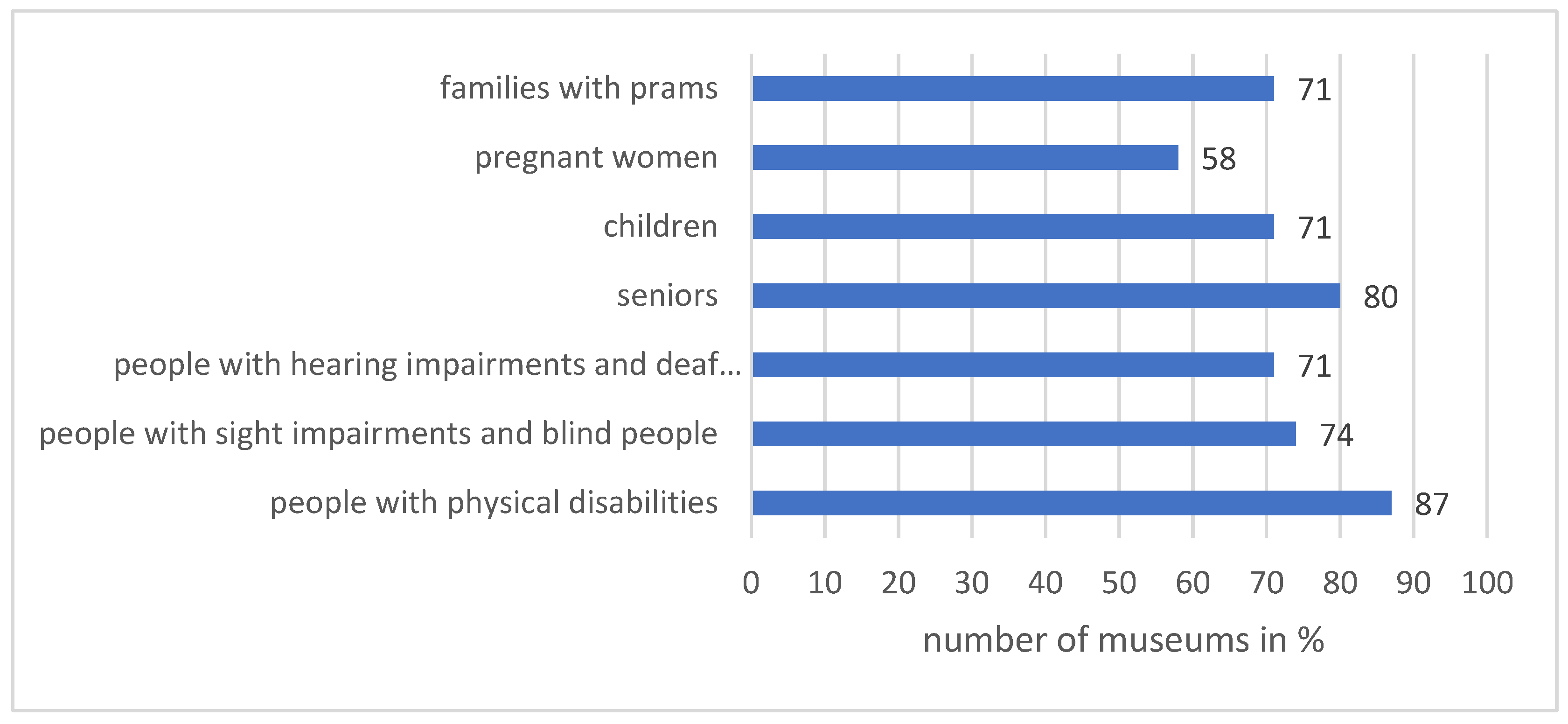

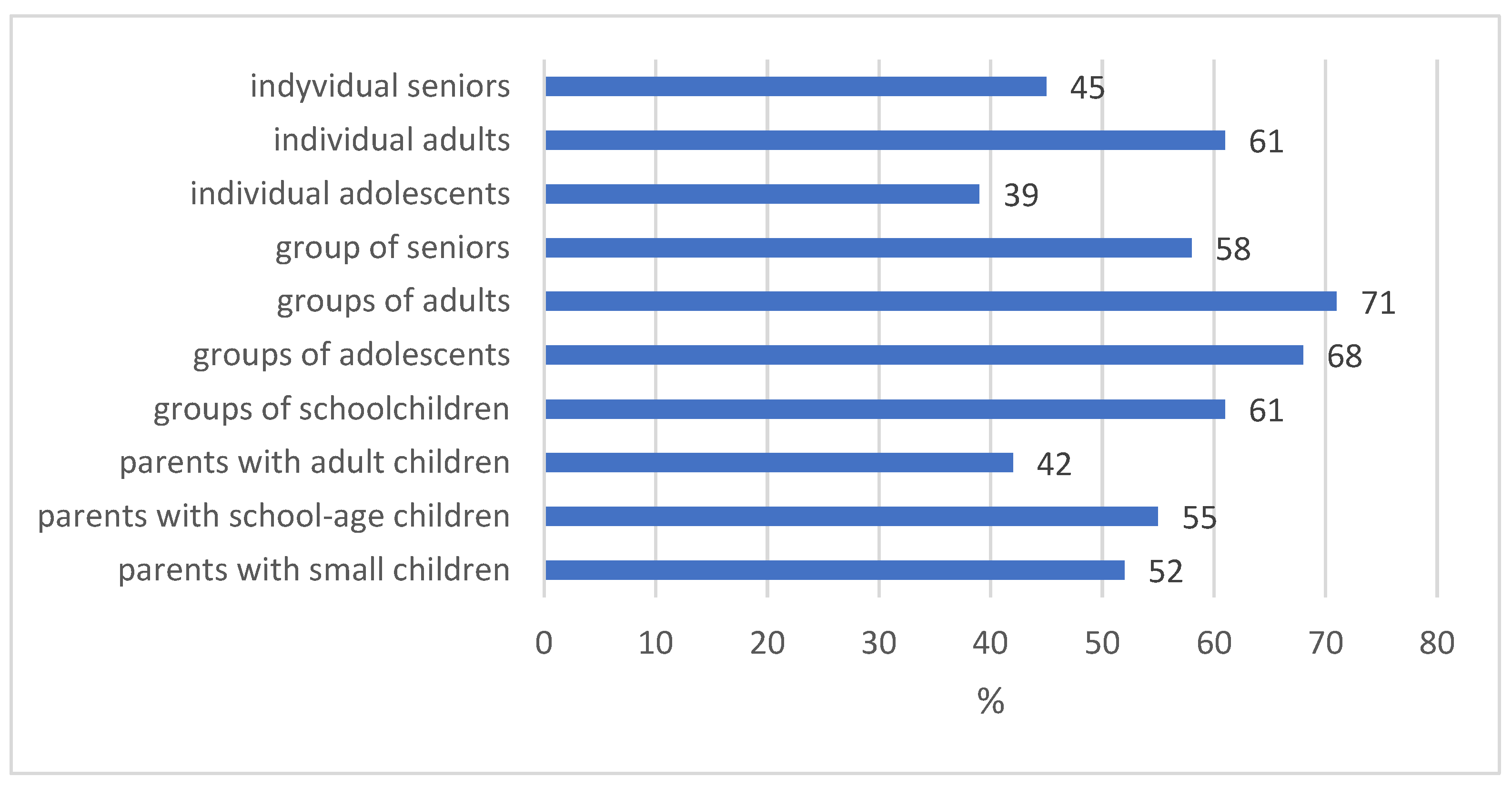

Figure 5 illustrates the principal visitor segments reported by museum managers. Groups of adults were in the majority in 71% of museums, with a slightly lower number of individual adults (61%). Groups of adolescents were reported by 68% of the museums, but individual adolescent visitors by only 38%. Also worthy of attention are groups of seniors (58%) and individual senior visitors (45%). A considerable percentage of museums indicated groups of schoolchildren (61%), as well as parents with school-age children (55%). Parents with small children were indicated as an important group in 52% of Krakow museums.

In response to the question on the total number of museum visitors with limited mobility and those with particular needs, including people with sight, hearing and cognitive impairments, seniors, families, pregnant women and small children, the majority of managers estimated this to be around 10%. The highest estimates were for people with physical disabilities, while in general, no participation was found of people with dietary restrictions.

Question 6 referred to museums employing people trained in providing assistance to people with particular needs. Almost all of the museums employ such people (97%), with only 3 museums not having such members of staff. In addition, museum staff were trained in providing assistance to people with particular needs, with 30% of museums having half of their staff trained in this regard.

The interviews revealed that the museums provide sufficient information on their websites regarding the accessibility of their premises for people with particular needs, as confirmed by 97% of museum managers, while guide dogs and other support animals are permitted in 87% of the museums.

Analysis was also conducted of the museum websites in terms of their functionality for disabled users, as well as the option to take virtual tours. In response to the needs of people with disabilities, Polish law has introduced the concept of so-called digital accessibility. This is one of the most important features of websites, mobile applications and other digital solutions, and is intended to help people with varying degrees of hearing, movement, sight and cognitive abilities in the use of such solutions. According to the requirements, all public entities, including museums, must ensure digital accessibility on their websites and mobile applications so that they fulfil the principles of perceivability, functionality, comprehensibility and compatibility [

46].

According to the

Bill of 4th April 2019 on the digital accessibility of the websites and mobile applications of public entities, museums are obliged to possess a so-called declaration of accessibility, which describes the accessibility of the museum’s premises for people with disabilities. This declaration informs such people of the solutions, but also the problems, that they may encounter on the website, on the mobile application and in the buildings themselves [

45]. The declaration of accessibility must fulfil specific content and technical requirements, and should be available for every language version in which content is provided on the website. In situations when the website is not available, the museum must still have a fully available declaration. The declaration of accessibility should be updated every year (by the end of March) and after every redesign or update of the website or application.

Analysis of the museums’ websites in terms of their accessibility for people with disabilities (

Table 3) reveals that they are best prepared from the point of view of compatibility and comprehensibility. These elements displayed the lowest number of errors (475 and 745 respectively). The greatest problem in the declaration of accessibility was found to be the perceivability of websites (3683), followed by their functionality (1695).

Assessment of individual museums also shows a certain key disproportion. In general summary, the best prepared museums in terms of the website declaration of accessibility, that is with the lowest number of problems, are: Wawel Royal Castle (99), Galicja Jewish Museum (110), and the Photography History Museum (112). Meanwhile, the largest number of problems, both those clearly identified by the software, as well as those indicated as warnings and those for manual verification, were found at the Home Army Museum (3141), which stood out considerably from the remaining museums.

In analysis of the accessibility of museums for people with disabilities, given the current ubiquitous access to various types of technical and multimedia solutions, the possibility of participating in virtual tours cannot be ignored. Virtual Tourism involves the computer presentation of actual places, in which the geometrical properties of the places are presented to the user in such a way as to give them the impression of actually being present in the place in question. Virtual tourism cannot exist without virtual reality and space, which uses computer technology to create the effect of a three-dimensional world in which objects give the impression of being spatially and physically present [

46]. A virtual tour is a simulation of an actual place in which the user can move about freely; it is a digital solution that mimics any place or space in three dimensions.

Virtual tours of museums bring great cognitive and educational benefits in faithfully providing users with experiences of visiting museums using one or several of their five senses [

47]. However, in the museums in question, this is not a popular form of presenting collections, and among the 15 museums analysed, only 7 offer such an option (

Table 3).

6. Discussion

Cultural tourism is key to the development of tourism in general around the world, especially in Europe. An ever-greater number of people are travelling for cultural reasons, and they are particularly interested in cultural heritage. Cultural tourism brings huge opportunities and is a growing trend. Around 40% of all tourists in the world can be considered as cultural tourists, and culture is also one of the most important motivations for European tourists [

48]. Museums can be defined as one of the most important cultural attractions that serve to satisfy the cognitive and emotional needs of cultural tourists. As such, they serve a key social function. In this context, they should be accessible to all groups of people [

49].

Currently, there is observable interest in social inclusion, defined as the process of creating the opportunities and resources necessary for people at risk of poverty and social exclusion to participate to some extent in economic, social and cultural life, wherever possible including people with disabilities [

50]. Social inclusion also involves social integration, which manifests itself on many level - educational, professional, recreational and regarding tourism - and assist in the individual development of people with disabilities. In line with this process are the activities of Krakow museums aimed at making it possible for people with disabilities to use museum resources on a par with other visitors. Our research results confirm that the majority of visitors to museums are adults (individuals and groups), with seniors in second place (in groups and individually), ahead of adolescents and other museum visitor segments. People with disabilities constitute around 10% of museum visitors, and queries about the possibility for such people to view museum exhibitions are sporadic (once a month). This is confirmed by the results of research conducted among students with disabilities from various Krakow educational institutions, who make use of ‘museums, theatres, exhibitions and cinemas’ relatively seldom (only 3% declared this to be once per month) [

24].

The analysed Krakow museums are best prepared to receive people with physical disabilities and seniors, while they are less well prepared for people with sight impairments and blind people, or people with hearing impairments and deaf people. A similar level of accessibility is seen for families with prams and with children.

The studied museums have taken action to improve their accessibility for people with particular needs. For people with physical disabilities, it is vital that museums ensure there are suitably wide doors and functioning lifts, as well as correctly designed communication routes. Other important features for people with limited mobility are inclines and ramps, lowered counters in reception/ticket offices, platforms and hoists, and automatic doors. The majority of the museums have induction loops installed for people with hearing impairments. One in three museums has amenities for blind people in the form of descriptions in Braille. Only 10% of the museums did not have any of these amenities.

It should be noted that there have been considerable improvements in the accessibility of Krakow museums for people with disabilities. The results of research from 1994 [

51] found that access to museums for people with disabilities (in the case of people with musculoskeletal dysfunction) was limited in the majority of cases to the ground floor, sometimes even only to certain rooms. In comparison, it can be observed that particular care is now taken to ensure that museums are fully accessible to various groups of people with particular needs.

The digitalisation of Krakow museums is not at an advanced stage. The websites of the museums studied are assessed positively in terms of their compatibility and comprehensibility with regard to their accessibility for people with disabilities. The greatest problem in the declaration of accessibility that the museums were required to present was with the perceivability and functionality of the websites. In research conducted into the websites of 30 museums in Bulgaria, it was found that the majority of the websites were below average and did not provide a satisfactory level of digital accessibility [

52]. Research on museums in Portugal indicated similar problems with the assessment of website perceivability and functionality, although the 576 Portuguese museum websites studied had a higher level than other tourist entities [

53].

The problem of the use of internet applications by Polish museums (including 2 in Krakow) during the Covid-19 pandemic was analysed by Gaweł [

34], indicating common use of applications such as Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Tik-Tok for communicating with potential visitors, and above all for promoting the museum as a tourist product. For example, the National Museum in Krakow has 103,000 followers on Facebook, 30,000 members on Instagram, and 1890 subscribers on YouTube. Similarly, Wawel Royal Castle has 140,000 followers on Facebook, 10,000 on Instagram, and over 3,000 subscribers on YouTube. Neither of these two flagship Krakow museums use the Tik-Tok application, which is highly popular among young people [

34].

The decided majority of the museums employ people for assisting clients with special needs, which suggests the need to suitably train staff. Unfortunately, the majority of tourism study programmes do not include subjects related to the accessibility of tourist attractions [

54].

7. Conclusions

The research indicates that Krakow museums are well prepared for receiving people with physical disabilities and seniors, but are less well prepared for receiving people with sight impairments and blind people, or people with hearing impairments and deaf people. Visitors to the museums included in the study are predominantly adults, adolescents and seniors. People with disabilities constitute around 10% of all visitors.

The majority of museum managers consider that the existence of premises unadapted for wheelchair users is a form of discrimination, but for many museums, especially those located in historical buildings, adapting the premises to the needs of such people is a significant technical and financial challenge. For example, only half of the museums have access to dedicated parking spaces. As far as is possible, museums install technical amenities providing access to their premises, especially their exhibitions. These amenities include above all doors of suitable width, lifts, correctly designed communication routes, induction loops for those with hearing impairments, and descriptions in Braille. The public spaces in the majority of the museums are adapted for shared use by both people with particular needs and those without. The museums also declare that they employ people trained in providing assistance to people with particular needs.

Analysis of the museums’ digital accessibility showed that their websites were best prepared from the point of view of compatibility and comprehensibility. The greatest problem in meeting the conditions of the declaration of accessibility was found to be the perceivability and functionality of the websites. Unfortunately, only one of the museums studied uses virtual tours as a convenient form of making collections available to people with disabilities. During the Covid-19 pandemic, this means of visiting was often the only possibility for viewing museum collections.

Another issue that could be the subject of future research is assessment of the possibility for value co-creation, that is providing experiences through the participation and interaction of people with disabilities. Experience consumption depends on the involvement of both providers (museum managers) and consumers (tourists) [

55].

The research demonstrated the significant importance of new technologies for accessible tourism. These can be used to remove physical barriers, as well as for improving the sharing of information and as tools for providing tourist experiences e.g. augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) [

56].

The activities undertaken by Krakow museums are part of the pillars of sustainable tourism [

57]. They aim to create equal access to cultural heritage resources, such as visiting a museum, for all people, regardless of their physical and mental capabilities. Thus, the offer of museums addressed to people with disabilities strengthens the position of the city distinguished by the Access City Award. Krakow is one of the few cities in Europe that has developed and implements a sustainable tourism policy. Access to cultural heritage resources for all stakeholders is included in the strategic objective of this document [

58].

Theoretical and practical significance of the research

The assessment presented in the article of the accessibility of museums for people with disabilities contributes to knowledge of the issues surrounding access to heritage for people with special needs. The research results are therefore in line with the phenomenon of social inclusion and inclusive tourism.

The activities described above, which aim to make museums accessible to various groups of people with disabilities, as well as the technical, organisational and informational amenities provided, can be used by museum managers as a case study of good practice.

The results of our research point to the need to conduct further analyses in order to identify barriers to the development of accessibility at tourist attractions, and to seek solutions for learning and disseminating good practices.

Limitations

The research is limited to one type of attraction, that is museums, and only one city. Also, the research included Krakow museums with more than 5,000 visitors per year. To obtain a fuller picture of museum accessibility, it would be worthwhile continuing the research in museums of various sizes and in various locations. This should include the context of the social surroundings, especially the attitudes of museum managers and tourism providers towards the problems of accessibility to cultural heritage for people with disabilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zygmunt Kruczek, methodology Zygmunt Kruczek, Katarzyna Gmyrek; software, Karolina Korbiel, validation, Danuta Ziżka Karolina Nowak; formal analysis Katarzyna Gmyrek; investigation, Danuta Ziżka; resources, Karolina Nowak; writing—original draft preparation Zygmunt Kruczek. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project financed from the Visegrad fund ‘Application of Principles of Inclusion in Tourism in V4 Countries’ 2023-2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicabl” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Disability and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ disability-and-health (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- UNESCAP 2009, Available online: https://www.accessibletourism.org/resources/takayama_declaration_top-e-fin_171209.pdf, accessed on 26 June 2023.

- Darcy, S., Ambrose, I., Schweinsberg, S., Buhalis, D. Universal Approaches to Accessible Tourism. W: D. Buhalis, S. Darcy (red.). Accessible Tourism. Concepts and Issues. 2011. Bristol: Channel View Publications, 300–316.

- Espinosa Ruiz A., Bonmatí Lledó C. (eds.). Manual de accesibilidad e inclusión en museos y lugares del patrimonio cultural y natural. 2013, Gijón.

- Michopoulou, E., Darcy, S., Ambrose, I., Buhalis D. Accessible tourism futures: the world we dream to live in and the opportunities we hope to have. 2015, Journal of Tourism Futures, 1 (3), pp.179 – 188. [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization; Fundación ACS. Manual on Accessible Tourism for All—Public-Private Partnerships and Good Practices; 2015, UNWTO: Madrid.

- Kruczek, Z.; Mazanek, L. Krakow as a Tourist Metropolitan Area. Impact of Tourism on the Economy of the City. Studia Peregietica 2019, 26. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Access – City Award 2010: Rewarding and inspiring accessible cities across the EU. 2011, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Scheyvens, R.; Biddulph, R. Inclusive tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 589–609. [CrossRef]

- Biddulph, R.; Scheyvens, R. Introducing inclusive tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 583–588. [CrossRef]

- Liasidou, S.; Umbelino, J.; Amorim, É. Revisiting tourism studies curriculum to highlight accessible and inclusive tourism. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2019, 19, 112–125. [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S., Daruwalla, P. S. Personal and Societal Attitudes to disability. Annals of Tourism Research, 2005, 32(3), 549–570. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chowdlhury, S. Investigating the barriers in a typical journey by public transport users with disabilities. J. Transp. Health 2018, 10, 361–368. [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S., Inherent complexity: Disability, accessible tourism and accommodation information preferences. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 816–826. [CrossRef]

- Tutuncu, O. Investigating the accessibility factors affecting hotel satisfaction of people with physical disabilities. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 65, 29–36. [CrossRef]

- Al Kahtani, S.J.H.; Xia, J.; Veenendaal, B. Measuring accessibility to tourist attractions. In: Proceedings of the Geospatial Science Research Symposium, 2011, Melbourne, Australia, 12–14.

- Jamaludin, M.; Kadir, S.A. Accessibility in Buildings of Tourist Attraction: A case studies comparison. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 35, 97–104.

- Francuz S., Calińska-Rogala D. Ocena przystosowania atrakcji turystycznych dla osób z niepełnosprawnościami w Polsce. Przedsiębiorczość i Zarządzanie. 2019, Tom XX | Zeszyt 2 | Część II | p. 315–328.

- Duda-Seifert M., Zajączkowski J. Accessibility of Wrocław tourist attractions for people with physical disabilities, „Tourism Role in the Regional Economy”, 2011, Vol. 3, Social, Health-Related, Economic and Spatial Conditions of Disabled People’s Tourism Development, Wyższa Szkoła Handlowa, Wrocław.

- Rucci, A.C.and Porto, N. Accessibility in tourist sites in Spain: does it really matter when choosing a destination? European Journal of Tourism Research, 2022, 31, 3108. [CrossRef]

- Santana, S.B.; Peña-Alonso, C.; Espino, E.P.C. Assessing physical accessibility conditions to tourist attractions. The case of Maspalomas Costa Canaria urban area (Gran Canaria, Spain). Appl. Geogr. 2020, 125. [CrossRef]

- Śledzińska J., Turystyka dla wszystkich. Dostępność infrastruktury turystycznej w Polsce dla osób z różnymi niepełnosprawnościami [w:] Wyrzykowski J., Marak J. (red.), Tourism role in the regional economy, Wrocław, Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny 2011.

- Popiel, M. Wybrane aspekty turystyki dostępnej w Krakowie w opinii studentów z niepełnosprawnością. Prace Komisji Geografii Przemysłu Polskiego Towarzystwa Geograficznego, 2017, 31(3), 50–63. [CrossRef]

- Porto, N., Clara Rucci A., Darcy s., Garbero N., and Almond B. Critical elements in accessible tourism for destination competitiveness and comparison: Principal component analysis from Oceania and South America. Tourism Management 2019, 75: 169–85. [CrossRef]

- Luiza, S. M. Accessible tourism-the ignored opportunity. Annals of Faculty of Economics, 2010, 1: 1154–57.

- Domínguez, T., J., Alén F., Alén E. Economic profitability of accessible tourism for the tourism sector in Spain. 2013, Tourism Economics 19: 1385–99. [CrossRef]

- Cockburn-Wootten, Cheryl, and Alison McIntosh. Improving the Accessibility of Tourism Industry in New Zealand. Sustainability 2020, 12: 10478. [CrossRef]

- Skalska, T. Identifying quality gaps in tourism for people with disabilities: Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA). Turyzm/Tourism, 2023, 33(1), 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Popovi´c, D., Slivar,I. Gonan Božac M. Accessible Tourism and Formal Planning: Current State of Istria County in Croatia. Administrative Sciences 2022. 12: 181. [CrossRef]

- Załuska, U., Kwiatkowska-Ciotucha, D., Grześkowiak, A., Travelling from Perspective of Persons with Disability: Results of an International Survey. Int. Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(17). [CrossRef]

- Kruczek Z., Nowak K. Wpływ pandemii COVID-19 na funkcjonowanie atrakcji turystycznych w Polsce. Warsztaty z Geografii Turyzmu, 2023, 13, 37-50.

- Xia, Y. How Has Online Digital Technology Influenced the On-Site Visitation Behavior of Tourists during the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Case Study of Online Digital Art Exhibitions in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10889. [CrossRef]

- Gaweł Ł. Museums without visitors? Crisis and revival - managing the "digital world" in Polish museums in times of pandemic. Sustainability, 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Page, S. J. Urban tourism, 1995, Routledge, London-New York.

- Fainstein S. S., Judd D. R. Cities as places to play, [w:] The Tourist City, D. R. Judd, S. S. Fainstein (red.), 1999, Yale University Press, New Haven, Londyn, s. 261–272.

-

This is where I wont to live. Krakow 2030. Krakow Development Strategy. Krakow Citu Council. 2018 Available online. https://www.bip.krakow.pl/?dok_id=94892, accessed 91.11.2023.

- Šauer M., Pařil V., Viturka M. Integrative potential of Central European metropolises with a special Focus on the Vishegrad countries. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 2019, 25(2): 219–238. [CrossRef]

- Kruczek, Z.; Szromek, A.R. The Identification of Values in Business Models of Tourism Enterprises in the Context of the Phenomenon of Overtourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1457. [CrossRef]

- Ziarkowski D. Oferta muzealna Krakowa, [w:] A. Niemczyk, R. Seweryn (red.). Turystyka muzealna. Przypadek Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie, 2015, Proksenia, Kraków.

- Kruczek Z., Nowak K. Frekwencja w polskich atrakcjach turystycznych w 2022 r. Polska Organizacja Turystyczna, 2023, Warszawa – Kraków. Available online (link:).

- Niemczyk A., Seweryn R. Dziedzictwo kulturowe magnesem przyciągającym turystów do wielkich miast (na przykładzie Krakowa), [w:] Marketing w rozwoju turystyki, J. Chotkowski (red.), Wydawnictwo Uczelniane Politechniki Koszalińskiej, 2009, Koszalin.

- Ruslin, R., Mashuri, S., Rasak, M., Alhabsyi, F., Syam, H. Semi-structured Interview: A methodological reflection on the development of a qualitative research instrument in educational studies. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME), 2022. [CrossRef]

-

www.tawdis.ne, Available online accessed 16.10.2023.

-

https://www.gov.pl/web/dostepnosc-cyfrowa, Available online accessed 16.10.2023.

- Stepaniuk, K., Wirtualne zwiedzanie w opinii internautów w Polsce, w: Ekonomia i Zarządzanie vol. 3 nr 3, Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Białostockiej, 2011, 75.

- Pawłowska, A., Matoga Ł., Wirtualne Muzea w Internecie – forma promocji i udostępniania dziedzictwa kulturowego czy nowy walor turystyczny? Turystyka Kulturowa 2014, 9, pp. 46-58.

-

https://www.cbi.eu/market-information/tourism/cultural-tourism/market-potential, accessed 167.10.2023.

- Gassiot Melian, Ariadna & Camprubí, R. The Accessibility of Museum Websites: The Case of Barcelona. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Krupa-Potoczny, M., Inkluzja społeczna osób z niepełnosprawnością na przykładzie działalności Fundacji Handicup Zakopane., Kształcenie Literackie. Dydaktyka polonistyczna, 8 (17) 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kruczek Z., Stanisławczyk K. Ocena dostępności walorów krajoznawczych i bazy hotelowej Krakowa dla turystów niepełnosprawnych. Folia Turistica, nr 5, 1994, s. 29-46.

- Todorov, T., Bogdanova, G., Todorova–Ekmekci, M. Accessibility of Bulgarian Regional Museums Websites, International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2022 28.

- Teixeira, P., Lemos, D., Carneiro, M.J., Eusébio, C., Teixeira, L. Web Accessibility in Portuguese Museums: Potential Constraints on Interaction for People with Disabilities. In: Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Gao, Q., Zhou, J. (eds) HCI International 2020 – Late Breaking Papers: Universal Access and Inclusive Design. HCII 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2020, vol 12426. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Liasidou, S., Umbelino J., Amorim E. Revisiting tourism studies curriculum to highlight accessible and inclusive tourism, Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, Kruczek, Z. Experience marketing at Polish museums and visitor attractions: the co-creation of visitor experiences, emotions and satisfaction, Museum Management and Curatorship: 2021, vol. vol. 36, issue 1, pp. 62-81. [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, O.M. Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) Technologies for Accessibility and Marketing in the Tourism Industry. In: ICT Tools and Applications for Accessible Tourism. IGI Global, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M., van der Duim, R., Peters, K., Klomp, J. Tourism and Inclusive Growth: Evaluating a Diagnostic Framework. Tourism Planning and Development 2020 . [CrossRef]

- Walas, B. (ed.) A sustainable tourism policy for Krakow in the years 2021-2028, Diagnosis and recommendations, Municipality of Krakow, 2021, ISBN 978-83-66039-72-8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).