Introduction

Analysis of spent blastocyst culture medium (SBM), by powerful biochemical analytical techniques such as Mass Spectrometry, Raman Spectroscopy and NMR, provide huge opportunities to develop non-invasive tests for blastocyst and embryomic competency [

1,

2]. One promising group of molecules being measured are collectively termed metabolites. These can be organic substrates, being taken up from the culture media and, or more specifically, organic products [

3], byproducts and intermediaries from cellular metabolic synthesis pathways of blastocyst cells [

4]. These may be deliberately secreted or simply leaked into the culture media [

5]. As such metabolomic analysis of SBM presents as an orthogonal, and therefore complimentary, approach to morphological (visual) and even PGT-A scoring.

The omics’ generation of techniques described can rapidly and sensitivity simultaneously resolve thousands of the potential metabolites found, including many not previously known or characterised. Furthermore, if output data from these omics technologies is coupled with artificial intelligence - machine learning (Ai/ML), biomarker and biomarker relationships to clinical situation can easily be established without first characterising the specific metabolites involved: Simply their detection and relative quantification as peaks on a spectra is all that is required [

6,

7].

In assisted reproductive medicine the frontier is the identification of IVF blastocysts that have the greatest potential to implant. Based on omics’ output spectra, multiple published reports, including our own, have described and claimed, Ai/ML algorithms of that can predicts which is the optimum IVF blastocyst to transfer [

8,

9,

10].

However, the actual aim is to improve IVF success rates, which is live birth rates [

11]. Whilst implantation is an important step towards that goal, there are many intermediate failures and losses: Implantation itself is often defined as a positive pregnancy test, but this can be transient and superficial attachment, such as seen in biochemical pregnancy [

12]; clear and prolonged, as in blighted ovum/anembryonic pregnancy or first trimester miscarriage [

13], and indeed highly elevated and progressive, as in later trimester spontaneous abortions [

14].

Although cutting edge, the move from a research concept to a robust operational system that can be utilised by Clinical IVF centres, multiple technical and operational parameters need to be overcome and standardised. Thus, previously we described the influence of hatching on the mass spectral markers detected in SBM and how that altered predictive algorithms [

15].

Here we describe how choosing the definition of outcomes and the actual biological reality of implantation, viability and data accuracy effects the development of practical real world applicability of these metabolite tests and Ai/ML algorithms.

Material and Methods

Prospective collection of Mass spectral data analysed between 2013 and 2021, over 12,000 SBM from pre-implantation data were analysed by MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry as previously described [

8]. The mass spectral data files were stored on a secure server and subsequently matched to clinical meta data when transferred and outcomes known.

The metadata included criteria such IVF Centre, chief embryologist, developmental day of blastocyst culture SBM sampling occurred (i.e., Day3 or Day5/6 days), hatched or non-hatched, fresh transfer, discarded of lyophilised for subsequent FET, Gardener score, ploidy (if tested) and outcomes if transferred. The outcomes were: not implanted, implanted, Biochemical Pregnancy, Blighted Ovum/Anembryonic pregnancy, spontaneous abortion and Ongoing pregnancy with fetal heart beat detected at 16plus weeks of gestation.

Test and Validation Set

The prediction algorithm generated were applied to a data set of Four hundred and forty individual blastocyst SBM MALDI-ToF Mass spectra, pre transfer spectra, meeting the following selection criteria: All came from a single IVF centre (VCRM) and the same Embryologist, were day 5, FET, hatched, but NOT PGT-A tested, and had outcome data recorded, and training set nieve.

Results

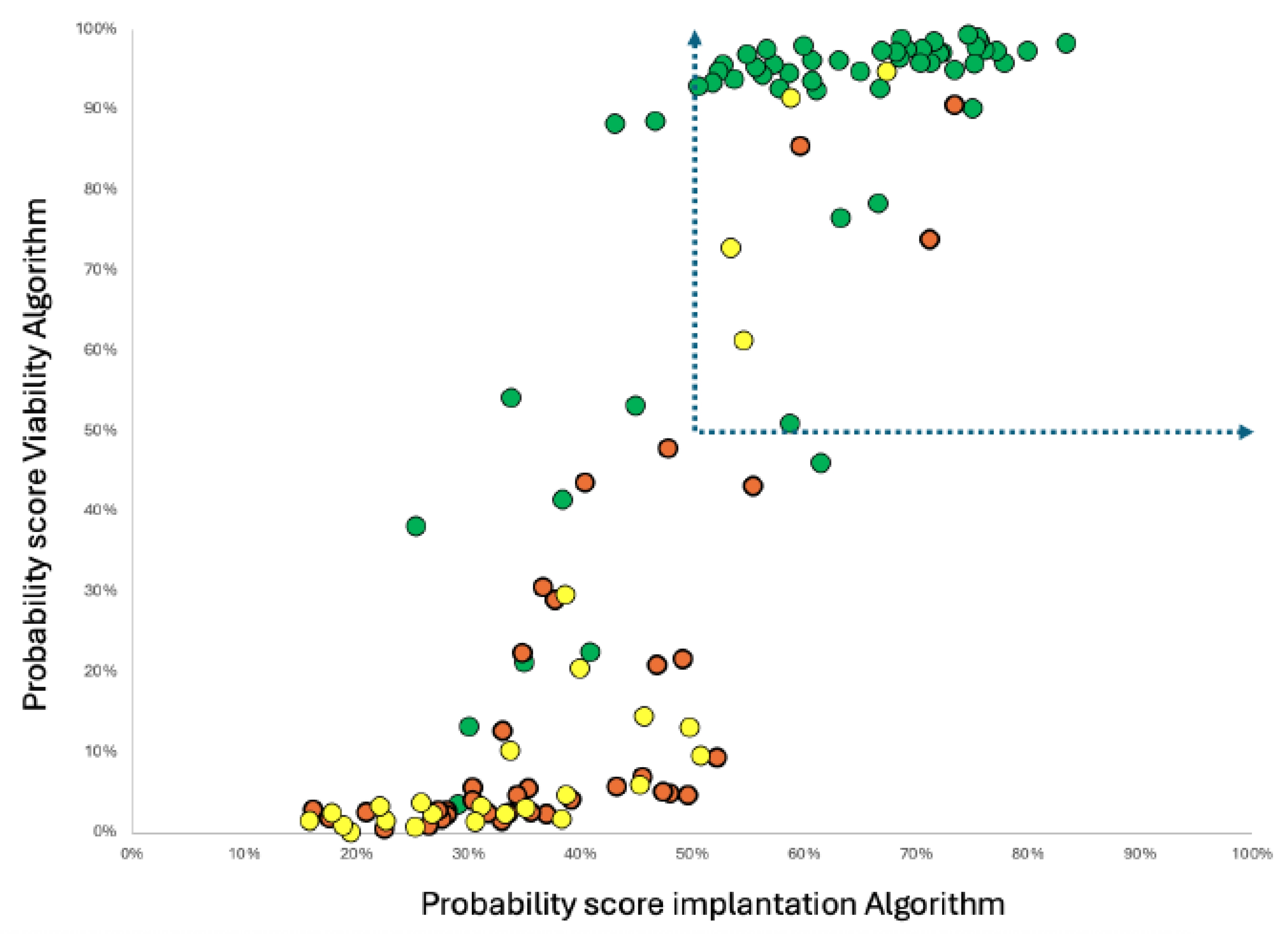

The two prediction algorithms gave probability based scores on either implantation or “Viable pregnancy” as the desired outcome. Although correlating they did not agree in the probability predictive scoring in a simple linear manner (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Plot of score values for implantation and viability when applied to the Ai/ML build data, illustrating non-linear regression correlation and group segregation of clinical outcomes : Green Dots - Blastocyst that implant AND ongoing embryo at 16 weeks plus, Yellow Dots - Blastocyst implanted but spontaneously aborted; Red Dots - Blastocysts that failed to implant. Dotted line arrows show cut off zone delineating positive fraction in a metabolic SBM testing to select blastocyst Embryo’s to transfer.

Figure 1.

Plot of score values for implantation and viability when applied to the Ai/ML build data, illustrating non-linear regression correlation and group segregation of clinical outcomes : Green Dots - Blastocyst that implant AND ongoing embryo at 16 weeks plus, Yellow Dots - Blastocyst implanted but spontaneously aborted; Red Dots - Blastocysts that failed to implant. Dotted line arrows show cut off zone delineating positive fraction in a metabolic SBM testing to select blastocyst Embryo’s to transfer.

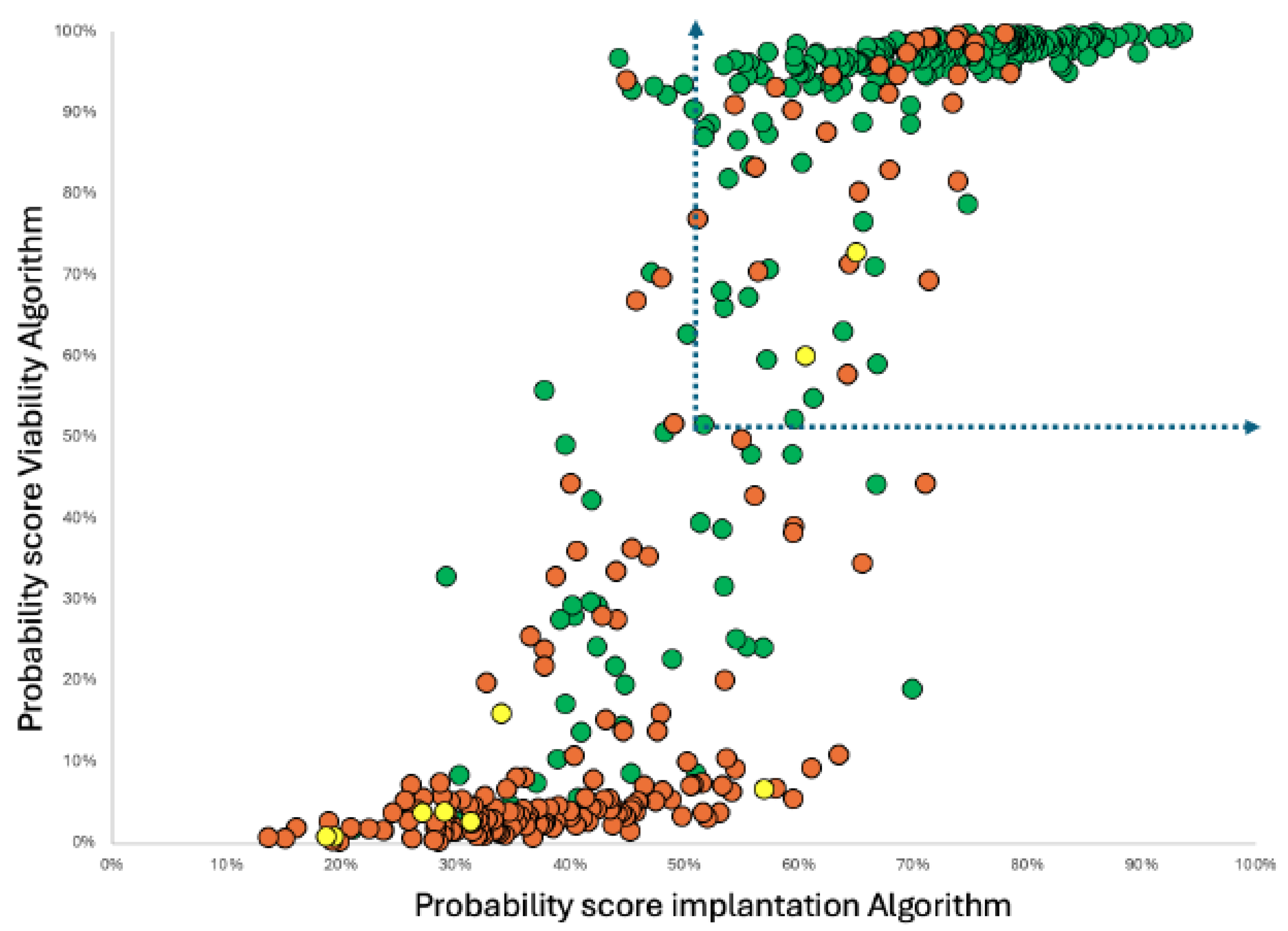

Figure 2.

Distribution Plot of score values for implantation and viability when applied to the nieve -test/validation data. Group segregation of clinical outcomes : Green Dots - Blastocyst that implant AND ongoing embryo at 16 weeks plus, Yellow Dots - Blastocyst implanted but spontaneously aborted; Red Dots - Blastocysts that failed to implant. Dotted line arrows show cut off Zone delineating positive fraction in a metabolic SBM testing to select blastocyst-embryo’s to transfer.

Figure 2.

Distribution Plot of score values for implantation and viability when applied to the nieve -test/validation data. Group segregation of clinical outcomes : Green Dots - Blastocyst that implant AND ongoing embryo at 16 weeks plus, Yellow Dots - Blastocyst implanted but spontaneously aborted; Red Dots - Blastocysts that failed to implant. Dotted line arrows show cut off Zone delineating positive fraction in a metabolic SBM testing to select blastocyst-embryo’s to transfer.

Indeed, although the correlation was evident and statistically significant, the non-linear sigmoidal regression fit indicates a complex relationship, explainable by two overlapping but distinct biological metabolisms.

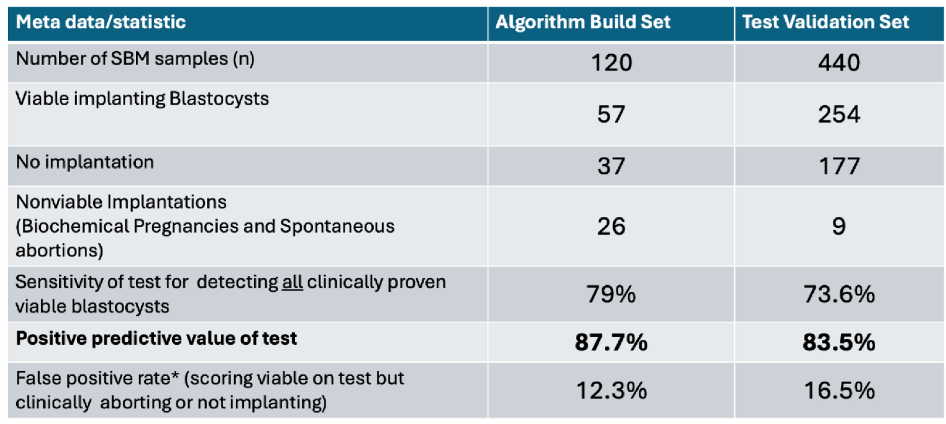

Interpreting clinical utility of such a metabolic profiled test for an IVF blastocyst embryo selection tool, the performance of the combined algorithm was evaluated as scores in both “implantation” and “viability” having to be greater than 50% on both algorithms. The performance in the validation set closely matched that of the training set data and indicated that this single delineation of high probability and low probability had excellent positive predictive test utility: If the blastocyst SBM spectra scored greater than 50% in both algorithms there is an 83% positive predictive value, i.e., if such a scored blastocyst were transferred it had an 83% probability of implantation

and a viable pregnancy (see

Table 1).

Table 1.

Meta data and performance characteristic in identifying viable implanting blastocysts.

Table 1.

Meta data and performance characteristic in identifying viable implanting blastocysts.

Discussion and Clinical Interpretation

Inherent Error and Bias in IVF Outcome Data Sets

At first glance sample data upon which metabolic omics’ prediction algorithms are built are straightforward, blastocyst SBM collected and (preferably tested pre-transfer) when transferred it either implanted and resulted in a pregnancy or did not implant.

However, the failure to implant is not solely down to the competence of the Blastocysts. Endometrial receptivity has been estimated to be responsible for IVF failures in anything from 20% to 2/3

rds of IVF transfers. Thus, there is a significant number of False Negatives (FN) in the data classification being fed into Ai/ML programmes and overfitting is common consequence [

16]. We have no way of correcting such errors of classification, yet Ai/ML relies on the accuracy of such classifications. This error has to be allowed for and an estimate of confidence in the data has to be allowed for when supervising the Ai/ML generation of algorithms. We are undercounting what is classified as True Oositives (TP), over counting True Negatives (TN). Thus the False positive (FP) and False Negatives (FN) are always going to be estimates. As such the calculation of accuracy (TP + TN/TP+TN+FP+FN) in any blastocyst selection test is going to be an unreliable statistic.

Given these errors, to achieve an algorithm accuracy score of 70 to 80% is the best logically expected, based on input misclassification; and therefore any system claiming 90% and over accuracy in prediction of blastocyst competence is highly likely to have over fitted the data [

17,

18].

Here, supervising the Ai/ML programme and limiting the branching levels of decision tree algorithms we mitigated the worst extremes of overfitting. Moving toward a “margin of error” compensation for the input data. Hence prediction probability output’s values of the SBM being from an implanting competent blastocyst never fell below 15% or exceeded 80%.

However, this is not the only reproductive physiological consideration concerning biological outcomes to take into account during the design and creation of a clinically useful IVF Blastocyst evaluation test.

Ethical Approval

All couples gave consent for the culture media to be used. The study was approved by VCRM’s Institutional Review Board (fshararaVCRMED20230126).

Conflicts of Interest

Dr Ray K Iles is Chief Scientific officer of Embryomic Ltd. and the Inventor of patents EP2976647B1 and EP3198279B1; Dr Sara Nasser is a Medical Advisor to Embryomic Ltd. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zmuidinaite, R.; Sharara, F.I.; Iles, R.K. “Current advancements in noninvasive profiling of the embryo culture media secretome,” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesaik; J Noninvasive Biomarkers of Human Embryo Developmental Potential PREprints.org 2025 https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202504.1568/v1.

- Gardner, D.K.; Harvey, A.J. Blastocyst metabolism. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 2015, 27, 638–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechniak, D.; Sell-Kubiak, E.; Warzych, E. The metabolic profile of bovine blastocysts is affected by in vitro culture system and the pattern of first zygotic cleavage. Theriogenology 2022, 188, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, E.; Canela, N.; Herrero P, Cereto, A. ; Gimeno, I.; Carrocera, S.; Martin-Gonzalez, D.; Murillo, A.; Muñoz, M. Metabolites Secreted by Bovine Embryos In Vitro Predict Pregnancies That the Recipient Plasma Metabolome Cannot, and Vice Versa. Metabolites 2021, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somorjai, R.L. Pattern recognition approaches for classifying proteomic mass spectra of biofluids. Methods Mol Biol. 2008, 428, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Guo, L.; et al. An end-to-end mass spectrometry data classification model with a unified architecture. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 19065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharara, F.I.; Butler, S.A.; Pais, R.J.; Zmuidinaite, R.; Keshavarez, S.; Iles, R.K. “BESST, a Non-Invasive computational Tool for Embryo selection using mas spectral profiling of embryo culture media. EMJ Repro Health 2019, 5, 59–60. Available online: https://www.emjreviews.com/reproductive-health/abstract/besst-a-non-invasive-computational-tool-for-embryo-selection-using-mass-spectral-profiling-of-embryo-culture-media/.

- Cheredath, A.; Uppangala, S.; CSA; Jijo, A.; RVL; Kumar, P.; Joseph, D.; GANG; Kalthur, G.; Adiga, S.K. Combining Machine Learning with Metabolomic and Embryologic Data Improves Embryo Implantation Prediction. Reprod Sci. 2023, 30, 984–994. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munné; S; Almansa, J.A.H.; Seth-Smith, M.L.; Perugini, M.; Griffin, D.K. Non-invasive selection for euploid

embryos: prospects and pitfalls of the three most promising approaches, Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 2025, 105077. [CrossRef]

- Claman, P.; Armant, D.R.; Seibel, M.M.; et al. The impact of embryo quality and quantity on implantation and the establishment of viable pregnancies. J Assist Reprod Genet 1987, 4, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeadna, A. , Son, W.Y., Moon, J.H., Dahan M.H., A comparison of biochemical pregnancy rates between women who underwent IVF and fertile controls who conceived spontaneously. Human Reproduction. 2015, 30, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Q.W.; Hua, R.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, Y.H. Blighted ovum in subfertile patients undergoing assisted reproductive technology. Nan Fang yi ke da xue xue bao= Journal of Southern Medical University. 2017, 37, 902–906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hawkins Bressler, L.; Correia, K.F.; Srouji, S.S.; Hornstein, M.D.; Missmer, S.A. Factors Associated With Second-Trimester Pregnancy Loss in Women With Normal Uterine Anatomy Undergoing In Vitro Fertilization. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2015, 125, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iles, R.K.; Zmuidinaite, R.; Iles, J.K.; Nasser, S. The Influence of Hatching on Blastocyst Metabolomic Analysis: Mass Spectral Analysis of Spent Blastocyst Media in Ai/ML Prediction of IVF Embryo Implantation Potential– To Hatch or Not to Hatch? Preprints 2025, 2025081450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliferis, C.; Simon, G. Overfitting, Underfitting and General Model Overconfidence and Under-Performance Pitfalls and Best Practices in Machine Learning and AI. In: Simon, G.J., Aliferis, C. (eds) Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Health Care and Medical Sciences. Health Informatics. Springer, Cham. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.L.; Choma, M.A.; Onofrey, J.A. Bias in medical AI: Implications for clinical decision-making. PLOS Digit Health. 2024, 3, e0000651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afnan, M.A.M.; Liu, Y.; Conitzer, V.; Rudin, C.; Mishra, A.; Savulescu, J.; Afnan, M. Interpretable, not black-box, artificial intelligence should be used for embryo selection. Human Reproduction Open 2021, 2021, hoab040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).