1. Introduction

Induction and formation of gums (gummosis) are found through the plant kingdom. Generally gums are induced by biotic and abiotic environmental factors such as bacterial and fungal infection, insect attack, mechanical and chemical injury, water stress, and other environmental stressors [

1]. All these factors have been shown to promote also ethylene synthesis in plant tissues. It was reported that ethylene or ethylene-releasing compounds (i.e. ethephon; 2-chloroethylphosphonic acid) stimulate gum formation in stone-fruit trees and their fruits of the Rosaceae, apricot, cherry, peach, plum, almond [

1,

2], but also in tulip (

Tulipa sp.) bulbs and other bulbous ornamental plants [

3].

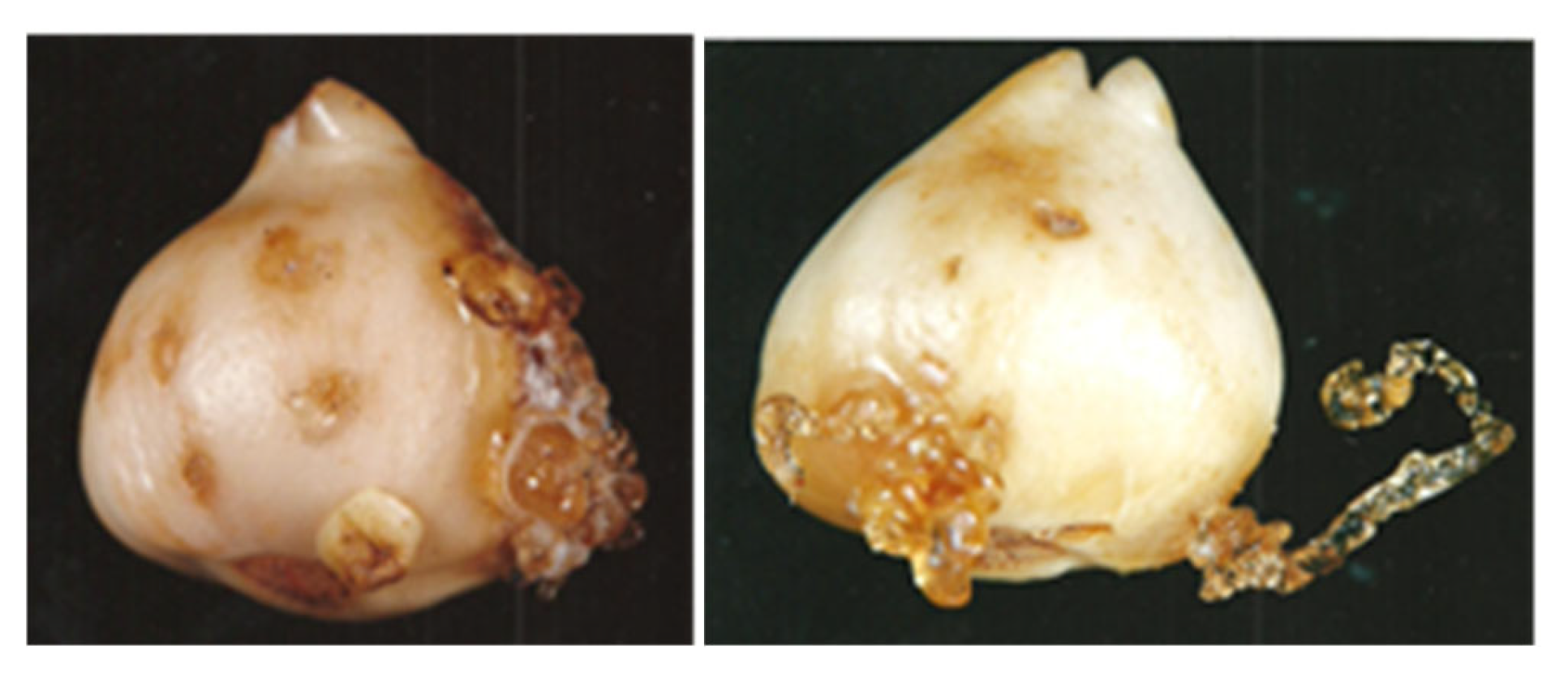

Tulip bulbs infected by

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.

tulipae have been shown to produce considerable quantities of ethylene, causing gummosis in diseased and healthy bulbs stored in the same conditions (

Figure 1) [

3,

4,

5]. These results suggest that ethylene is a common factor involved in the induction of gummosis [

1].

Figure 1.

Gummosis in tulip bulbs cv. Apeldoorn induced by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipe (on left) and by ethephon (2-chloroethylphosphonic acid) – ethylene releasing compounds (on right).

Figure 1.

Gummosis in tulip bulbs cv. Apeldoorn induced by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipe (on left) and by ethephon (2-chloroethylphosphonic acid) – ethylene releasing compounds (on right).

On the other hand it has been shown that jasmonates have a promoting effect on the induction and/or production of gums in tulip bulbs and in stone-fruit trees and their fruits of Rosaceae family, such as cherries, plums, peaches, apricots [

6].

This was reported that a rapid increase in endogenous levels of jasmonates, mainly Jasmonic acid (JA), occurs in plants or their organs under stress conditions, e.g. after mechanical wounding, under osmotic stress conditions and after pathogens infection or insect attack [

7]. These facts strongly suggest that jasmonates are important key compounds involved in induction and/or production of gums in plants together with or without endogenous ethylene. Jasmonates have also been well known to control ethylene production in plant tissues [

7].

Gums are complexes of different substances, but most important constituents are polysaccharides of highly individual structure [

1]. The composition of tulip gum polysaccharides has been determined and shown to be consisted of glucuronoarabinoxylan with an average molecular weight of ca 700 kDa [

8]. It is well known that different kinds of polysaccharides function in plants as molecular signals (elicitors) that regulate growth, development and survival in the environment, through elicitation of various physiological and biochemical processes [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. It is possible that a polysaccharides of tulip gums act as an elicitor, which regulates some processes connected with or responsible for mycelial growth and other physiological processes of

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.

tulipae. Saniewska [

18] studied the effect of gums induced by

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.

tulipae in tulip bulbs on the mycelium growth and development of the pathogen

in vitro.

It was previously demonstrated that incubation of

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.

tulipae spores in the water suspension of tulip gums stimulated spore germination and greatly induced the appearance of red-colored hyphae and medium. It seems that the polysaccharide of tulip gums is the main agent responsible for the elicitation of the secondary metabolite(s) by the hyphae of the pathogen [

19]. In the present study the red colored pigment occurring in

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.

tulipae elicited by tulip gums was identified.

2. Materials and Methods

The spores of isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipae were produced from 10 day old cultures grown on PDA medium. After that period the mycelium was washed with 20 cm3 of sterilized water. Then the mycelium was smoothed by glass stirrer for liberation of spores and after 30 minutes spores were separated from mycelium using filter paper. The spore density in 1 cm3 of filtered suspension estimated under a microscope using a Büker camera was 1.5 x 106. Tulip gums, were dissolved in distilled and sterilized water. To a water solution of gum with a volume of 19 cm3, 1 cm3 of F. oxysporum f. sp. tulipae spores was added. The density of the pathogen was then checked again and determined to be 1.2 x 106. The total concentration of tulip gums was 1.0% (w/w). As a control distilled water with F. oxysporum f. sp. tulipae spores was used. The solution was kept at room temperature for 15 days with occasional shaking, The mycelium was sampled after 7 and 15 days.

The lyophilized colored mycelium was extracted with 70% MeOH,. The extract was evaporated in vacuo, dissolved in MeOH and used for analysis. Thermo Finningan ICQ Advantage MAX mass spectrometer was used for quantitation and identification of compounds. An LC system consisting of Finnigan Surveyor pump equipped with a gradient controller, an automatic sample injector and Photodiode Array Detector (PDA) was used. The separation was performed on a 250 x 4 mm i.d., 5 μm Eurospher 100 C18 column (Knauer, Germany). A mobile phase consisted of 0.05% acetic acid in water (B) and 0.05% acetic acid in acetonitrile (A) was used for the separation. The flow-rate was kept constant at 0,5 mL/min for a total run time of 60 min. The system was run with a gradient program: 18% A to 36% A in 55 min, 36% A to 100% A in 20 min. The sample injection volume was 25 μL. Quantitation was based on external standardization by employing calibration curves for commercial standard in the range 0.0362 – 6.94 μg/mL. Standard was prepared in methanol prior to analysis. Structural analyses were performed with Thermo Finnigan LCQ Adventage Max ion-trap mass spectrometer with an electrospray ion source coupled to the HPLC system described above. The spray voltage was set to 4.2 kV and a capillary offset voltage –60 V. All spectra were acquired at a capillary temperature of 220 °C. The calibration of the mass range (400–2000 Da) was performed in negative ion mode. Nitrogen was used as sheath gas and the flow rate was 0.9 L/min. The structure of compounds was confirmed on the basis of pseudomolecular ion formation.

3. Results

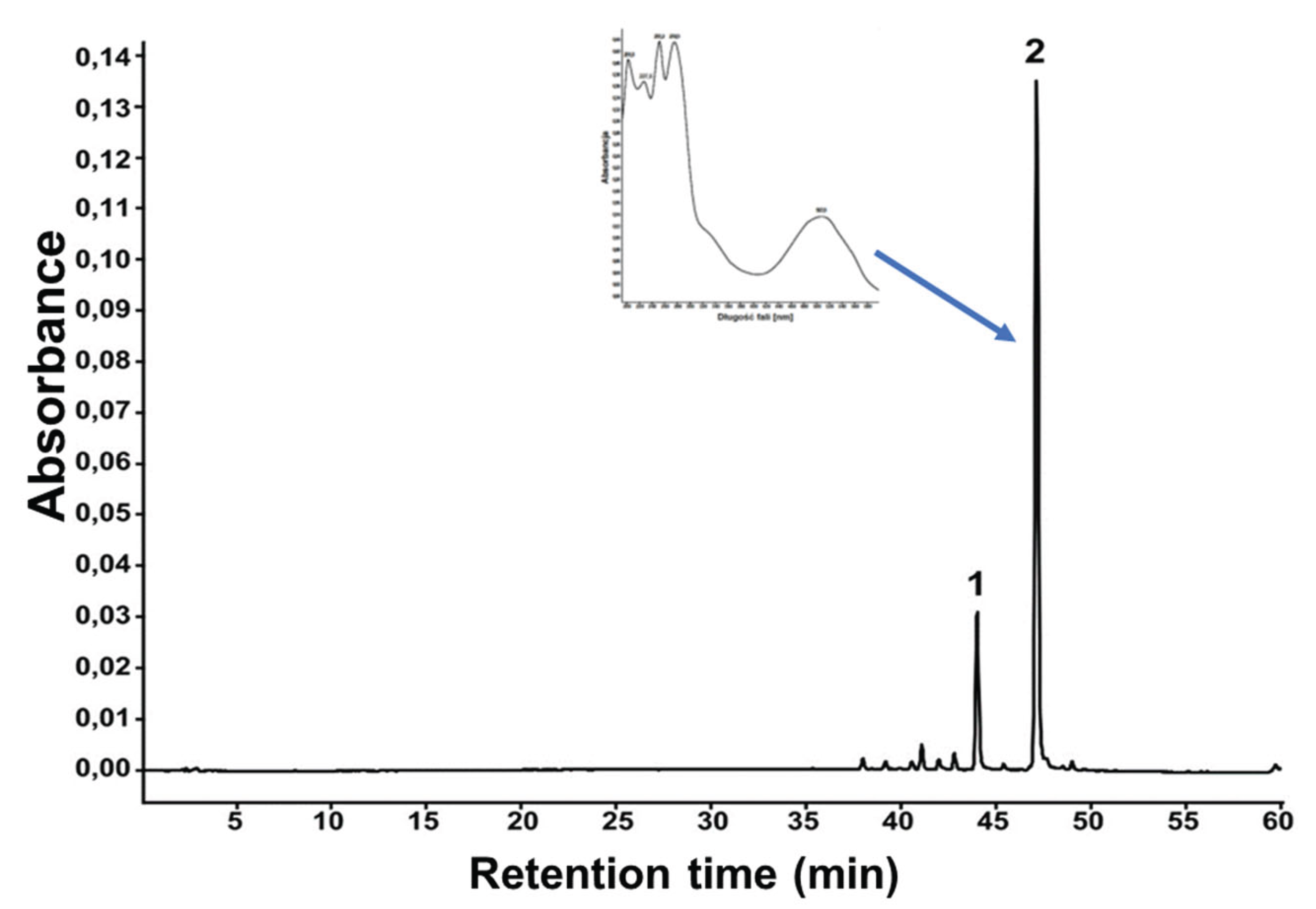

Incubation of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipae in water solution of tulip gums resulted in the appearance or red color product in mycelium. Lyophilized mycelium extract was analyzed with liquid chromatography, which revealed two dominant peaks (1: R

t = 44.02 min. and 2: R

t = 47.15 min.) in the chromatogram (

Figure 2). Based on the peak area these two peaks made over 90% of total. Their chemical structures were confirmed by comparing UV and MS data with those previously reported.

Figure 2.

The UV chromatogram of the extract from mycelium of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipae grown in tulip gum solution.

Figure 2.

The UV chromatogram of the extract from mycelium of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipae grown in tulip gum solution.

The UV spectrum taken from PDA detector of dominant compound

2 exhibited λ

max at 201.8, 227.6, 251.2, 274.9, 336sh and 507,8 nm (

Figure 2), and

m/z value of 381 in negative mode [M-H]

-. These values were similar to those obtained previously for bikaverin (6,11-dihydroxy-3-methoxy-1-methylbenzo[b]xantene-7,10,12-trione) the naphthoquinone pigment found in the wild

Fusarium oxysporum LCP531 strain [

20].

Compound

1 exhibited λ

max at 201.5, 227.5, 251.4, 275.2, 336sh and 508.2 nm and

m/z value of 367 in negative mode [M-H]

-. These values were quite similar to compound

2 and were identical to those obtained previously for norbikaverin (6,10,11-trihydroxy-3-methoxy-1-methylbenzo[b]xantene-7,8,12-trione] [

20].

The other minor peaks, the peak area of which made up less than 10% of total peak area were based on absorption spectra estimated as bikaverin related compounds, but their structures were not confirmed in this study. Presumably these were yellow naphthoquinone pigments (absorption maxima at 441 nm) reported previously [

20].

Both bikaverin and norbikaverin content in the mycelium of

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.

tulipe were determined after 7 and 15 days of incubation (

Table 1). After 7 days of incubation intracellular concentration of bikaverin 2.94 mg/100 mg mycelial dry matter and was nearly 4.5 higher than that of norbicaverin. Incubation of the solution for the next 8 days resulted in nearly doubled concentration of both naphthoquinones.

Table 1.

Bikaverin and norbikaverin content (mg/100 mg dry matter) in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipe mycelium grown with tulip gum solution.

Table 1.

Bikaverin and norbikaverin content (mg/100 mg dry matter) in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipe mycelium grown with tulip gum solution.

| Sample |

Norbikaverin

(Rt=44.02) |

Bikaverin (Rt=47.15) |

Total |

| Mycelium after 7 days |

|

|

|

| 0.64 ± 0.06 |

2.94 ± 0.26 |

3.58 ± 0.32 |

| |

|

|

| Mycelium after 15 days |

1.02 ± 0.11 |

4.62 ± 0.55 |

5.64 ± 0.62 |

| |

|

|

4. Discussion

Fungal secondary metabolites display diverse biological activities. They may act as phytotoxins causing damages to plants, have important roles in other interactions with other plants or may exhibit antimicrobial activities and be involved in competition for survival with other microbes. Bikaverin, the reddish pigment, is produced by different fungal species, especially those belonging to the genus Fusarium. This compound shows antibiotic activity against certain fungi and protozoa [

21,

22], nematicidal activity [

23] and anticancer activity [

24,

25,

26], but its biological function in Fusarium remains unknown [

26,

27].

It was reported that the synthesis of bikaverin is regulated by the culture conditions, such as carbon and nitrogen sources, calcium content, pH and many other factors [

28,

29,

30]. For example, in

Fusarium fujikuroi fungus the synthesis of bikaverin was induced by nitrogen starvation and acidic pH, and it was favored by aeration, and sulfate and phosphate starvation [

26].

Species of genus Fusarium produced also other red coloured naphthoquinone metabolites [

20,

31,

32].

Poly- or oligosaccharides are the most well studied signal molecules in elicitors signal transduction. Many elicitors, such as chitin, chitosan, xyloglucans, β-glucans and their fragments, oligogalacturonides, laminarin, exhibit elicitor activity across different plant species and highly induce phytoalexins in plants, suggesting that different plants possess some common receptors to sense these signals [

33]. One oligosaccharide elicitor can be recognized by several plants through their receptors with similar binding properties [

34]. Dass and Ramawat [

35] showed that gum arabic obtained from

Acacia senegal (arabinogalactan-proteins) and mesquite gum obtained from

Prosopis cineraria (arabinogalactan-proteins) evidently increased guggulsterone production in cell cultures of

Commiphora weightii. Water-extracted mycelial polysaccharide prepared from the endophytic fungus

Fusarium oxysporum Dzf17 isolated from the rhizomes of

Discorea zingiberensis evidently increased diosgenin accumulation in cell suspension culture of

D. zingiberensis [

36]. Chitosan, pectin and alginate enhanced production of anthocyanin in

Vitis vinifera cell suspension cultures [

37]. In

Cocos nucifera cell culture treatment with chitosan enhanced production of different secondary metabolites, e.g., p-hydroxbenzoic acid, p-coumaric acid and ferulic acid [

38]. Chitosan/chitin and pectin were effective in inducing of anthraquinone synthesis in cultured cells of

Morinda citrifolia [

39]. Gum arabic significantly promoted accumulation of phenolic acids, particularly 3-0-glucosyl-resveratrol, in

Vitis vinifera cultures, as well in the culture medium [

37]. Letarte et al. [

40] showed that arabinogalactan-protein from gum arabic increased microspore viability and induced embryogenesis in the microspore culture of wheat (

Triticum aestivum), and finally obtained regenerated green plants. Arabinogalactan-protein from cashew-nut (

Anacardium occidentale) gum greatly stimulated somatic embryogenesis in carrot culture and enhanced of the conversation rate of somatic embryos into plantlets [

41].

The induction of red colour pigment in mycelium of

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.

tulipae by tulip gums was previously reported, but its chemical structure was not confirmed [

42]. In present study the red color pigment was identified to be a mixture of bikaverin and norbicaverin. Their concentration in mycelium was quite high, which may suggest that this process can be applied in pigment production for industrial purposes. However, it is interesting to mention that tulip gums induced pigment production exclusively by

Fusarium oxysporum pathogenic for tulip bulbs. These gums did not elicit the red pigment formation through mycelium of

F. oxysporum f. sp.

callistephi,

F. oxysporum f. sp

. dianthi and

F. oxysporum f. sp.

narcissi [

42]. These pathogens are not pathogenic for tulip bulbs and tulip gums did not stimulate linear mycelium growth of these pathogens on CzDA medium [

43].

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, M.S.; methodology, M.S.; investigation, A.J.B., E.W,L., J.G.K., A.S; writing—original draft preparation, M.S, W.O.; writing—review and editing, M.S.,W.O.; supervision, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Data Availability Statement

Strains of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipae are available at Research Institute of Horticulture, Konstytucji 3 Maja 1/3, 96-100 Skierniewice, Poland

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LC |

Liquid Chromatography |

| MeOH |

Methanol |

| MS |

Mass Spectrometry |

| PDA |

Photodiode Array Detector |

| Rt

|

Retention Time |

| UV |

Ultra Violet |

References

- Boothby, D. Gummosis of stone-fruit trees and their fruits. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1983, 34, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniewski, M.; Ueda, J.; Miyamoto, K.; Horbowicz, M.; Puchalski, J. Hormonal control of gummosis in Rosaceae. J. Fruit Orn. Plant Res. 2006, 14 (Suppl. 1), 1137–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Kamerbeek, G.A.; de Munk, W.J. A review of ethylene effects in bulbous plants. Sci. Hort. 1976, 4, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniewska, A.; Dyki, B.; Jarecka, A. Morphological and histological changes in tulip bulbs during infection by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipae. Phyt. Polon. 2004, 34, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Saniewski, M.; Miyamoto, K.; Okubo, H.; Saniewska, A.; Puchalski, J.; Ueda, J. Gummosis in tulip (Tulipa gesneriana L.): Focus on hormonal and carbohydrate metabolism. Floricul. Ornam. Biotech. 2007, 1, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Saniewski, M.; Puchalski, J. The induction of gum formation in the leaf, stem and bulbs by methyl jasmonate in tulips. Bull. Polish Acad. Sci., Biol. Sci. 1988, 36, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Saniewski, M. The role of jasmonates in ethylene biosynthesis. In: Biology and Biotechnology of the Plant Hormone, Ethylene, Kanellis, A.K., Chang, C., Grierson, D (Eds) Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1997, pp 39-45.

- Skrzypek, E.; Miyamoto, K.; Saniewski, M.; Ueda, J. Jasmonates are essential factors inducing gummosis in tulips: mode of action of jasmonates focusing on sugar metabolism. J. Plant Phys. 2005, 162, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldington, S.; McDougall, J.; Fry, S.C. Structure-activity relationship of biologically active oligosaccharides. Plant Cell Environ. 1991, 14, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvill, A.; Augur, C.; Bergmann, C.; Carlson, R.W.; Cheong, J.-J.; Eberhard, S.; Hahn, M.G.; Lo, V-M.; Marfe, V.; Meyer, B.; Mohhnen, D.; O´Neill, M.A.; Spiro, M.D.; Van Halbeek, H.; York, W.S.; Albersheim, P. Oligosaccharides that regulate, development and defense responses in plants. Glycobiol. 1992, 2, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côte, F.; Hahn, M.G. Oligosaccharins: structures and signal transduction. Plant Mol. Biol. 1994, 26, 1379–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creelman, R.A.; Mullet, J.E. . Oligosaccharins, brassinolides, and jasmonates: Notraditional regulators of plant growth, development, and gene expression. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebel, J.; Mithöfer, A. 1998. Early events in the elicitation of plant defence. Planta 1998, 206, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, N.; Minami, E. Oligosaccharides signaling for defence responses in plant. Physiol. Mol. Plant Path. 2001, 59, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radman, R.; Saez, T.; Bucke, C.; Keshavarz, T. Elicitation of plants and microbial systems. Biotech. Appl. Bioch. 2003, 37, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delattre, C.; Michaud, P.; Courtois, B.; Courtois, J. 2005. Oligosaccharides engineering from plants and algae applications in biotechnology and therapeutics. Minerva Biotech. 2009, 17, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Courtois, J. Oligosaccharides from land plants and algae: production and applications in therapeutics and biotechnology. Curr. Op. Microb. 2009, 12, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniewska, A. The effect of gums induced by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipae in tulip bulbs on the mycelium growth and development of the pathogen in vitro. Zesz. Probl. Post. Nauk Roln. 2002, 481, 577–583. [Google Scholar]

- Saniewski, M.; Saniewska, A.; Jarecka-Boncela, A.; Węgrzynowicz-Lesiak, E.; Góraj, J.; Urbanek, H. Elicitation of secondary metabolites by tulip gums in mycelium of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipae. Acta Hort. 2011, 917, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeau, J.; Petit, P.; Dufosse, L.; Caro, Y. Putative metabolic pathway for the bioproduction of bikaverin and intermediates thereof in the wild Fusarium oxysporum LCP531 strain. ABM Expr. 2019, 9, 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, J.; Fuska, J.; Kuhr, I.; Kuhrová, V. Bikaverin, an antibiotic from Gibberella fujikuroi effective against Leishmania brasiliensis. Folia Microbiol. 1970, 15, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.W.; Kim, H.Y.; Choi, G.J.; Lim, H.K.; Jang, S.O.; Lee, S.; Sung, N.D.; Kim, J.C. Bikaverin and fusaric acid from Fusarium oxysporum show antioomycete activity against Phytophthora infestans. J. Appl. Microb. 2008, 104, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.R.; Son, S.W.; Han, H.R.; Choi, G.J.; Jang, K.S. ; Choi, Y,H. Nematicidal activity of bikaverin and fusaric acid isolated from Fusarium oxysporum against pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Plant Path. J. 2007, 23, 318–321. [Google Scholar]

- Fuska, J.; Proksa, B.; Fusková, A. New potential cytotoxic and antitumor substances I. In vitro effects of bikaverin and its derivatives on cells of certain tumors. Neoplasma 1975, 22, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Henderson, J.F.; Battell, M.L.; Zombor, G.; Fuska, J.; Nemec, P. Effects of bikaverin on purine nucleotide synthesis and catabolism in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells in vitro. Biochem. Pharm. 1977, 26, 1973–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limon, M.; Rodriguez-Ortiz, R.; Avalos, J. Bikaverin production and applications. Appl. Microb. Biotech. 2010, 87, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chełkowski, J.; Zajkowski, P.; Visconti, A. Bikaverin production of Fusarium species. Mycot. Res. 1992, 8, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, W.; Avalos, J.; Creda-Olmedo, E.; Domenech, C.E. Nitrogen availability and production of bikaverin and gibberellins in Gibberella fujikuroi. FEMS Microb. Lett. 1999, 173, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiemann, P.; Willmann, A.; Straeten, M.; Kleigreve, K.; Beyer, M.; Humpf, H.-U.; Tudzynski, B. Biosynthesis of the red pigment bikaverin in Fusarium fujikuroi: genes, their function and regulation. Mol. Microb. 2009, 72, 931–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ortiz, R.; Metha, B.J.; Avalos, J.; Limon, M.C. Stimulation of bikaverin production by sucrose and salt starvation in Fusarium fujikuroi. Appl. Microb. Biotech. 2010, 85, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medentsev, A.G.; Arinbasarova, A.; Akimenko, B.V.K. Biosynthesis of naphthoquinone pigments by fungi of genus Fusarium. Appl. Bioch. Microb. 2006, 41, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimble, M.A; Duncalf, L.J.; Nairn, M.R. Pyranonaphthoquinone antibiotics isolation, structure and biological activity. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1999, 16, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Davis, L.; Verpoorte, R. Elicitor signal transduction leading to production of plant secondary metabolites. Biotech. Adv. 2005, 23, 283–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, M.; Matsumura, M.; Ito, Y.; Shibuya, N. High-affinity binding proteins for N-acetylchitooligosaccharide elicitor in the plasma membranes from wheat, barley and carrot cells: conserved presence and correlation with the responsiveness to the elicitor. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Ramawat, K.G. Elicitation of guggulsterone production in cell cultures of Commiphora wightii by plant gums. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2009, 96, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Mou, Y.; Shan, T.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhou, L. Effects of polysaccharide elicitors from endophytic Fusarium zingiberensis. Molecules 2011, 16, 9003–9016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Kastell, A.; Mewis, I.; Knorr, D. ; Smetanska, I. Polysaccharide elicitors enhance anthocyanin and phenolic acid accumulation in cell suspension cultures of Vitis vinifera. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2012, 108, 401–409. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, M.; Karun, A.; Mitra, A. Accumulation of phenylpropanoid derivatives in chitosan-induced cell suspension culture of Cocos nucifera. J. Plant Physiol. 2009, 166, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doernenburg, H.; Knorr, D. Effectiveness of plant-derived and microbial polysaccharides as elicitors for anthraquinone synthesis in Morinda citrifolia cultures. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1994, 42, 1048–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letarte, J.; Simion, E.; Miner, M.; Kasha, K.J. Arabinogalactans and arabinogalactan-proteins induce embryogenesis in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) microspore culture. Cell Biol. Morph. 2006, 24, 691–698. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Netto, A.B.; Pettolino, F.; Cruz-Silva, C.T.A.; Simas, F.F.; Bacic, A.; Carneiro-Leao, M.M.; Iacomini, M.; Maurer, J.B.B. Cashew-nut tree exudate gum: Identification of an arabinogalactan-protein as a constituent of the gum and use on the stimulation of somatic embryogenesis. Plant Sci. 2007, 173, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniewski, M.; Saniewska, A.; Jarecka-Boncela, A.; Węgrzynowicz-Lesiak, E.; Góraj, J.; Urbanek, H. Elicitation of secondary metabolites by tulip gums in mycelium of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. tulipae. Acta Hort. 2011, 917, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniewska, A. Wpływ gum indukowanych w cebulach tulipana przez Fusarium oxysporum Szlecht. f. sp. tulipae na wzrost i rozwój form specjalnych Fusarium oxysporum niepatogenicznych dla tulipanów. Zesz. Probl. Post. Nauk Roln. 2002, 488, 773–778. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).