1. Introduction

Energy access to clean, affordable, and dependable energy continues to be a global challenge, especially for remote and off-grid areas of Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and small island developing nations. In spite of the latest innovations in decentralized renewable energy technologies, for instance, solar photovoltaic (PV), small-scale winds, and hybrid mini-grids, numerous communities rely on biomass and diesel generators as major energy sources [

1,

2,

3]. The traditional systems not only happen to be carbon-intensive but also carry major health, environmental, and economic risks because of the high costs of fuel, unhealthy air, and energy insecurity exposure [

3,

4].

Green hydrogen offers a potential solution to these challenges and to revamping the energy mix of unserved regions. Green hydrogen, produced by water electrolysis with renewable electricity, is a storable, versatile zero-emission energy carrier. Separation of energy generation from consumption with the enabling of long-duration storage, it offers a complementary solution to variable renewable energy sources such as solar and wind [

1,

3,

5]. Hydrogen, compared to classical batteries, can offer multi-day or seasonal storage, for which it is particularly suited for locations with weak or non-existent grid connectivity.

Emerging energy transition strategies of nations and regions, such as the European Green Deal, the Hydrogen Society Roadmap of South Africa, and the Chinese 30.60 decarbonization strategy, recognize green hydrogen as the key net-zero technology [

2,

6,

7]. These strategies appreciate the capacity of hydrogen to decarbonize sectors, build energy system flexibility, and create value chains for a green industrial future. For emerging regions, green hydrogen presents the promise of energy sovereignty, green jobs, and climate shock resilience as well.

However, several challenges still hamper the deployment of green hydrogen technologies, especially in remote, resource poor locations. High costs for electrolyzer systems, scarce access to clean water, low availability of technical knowledge, and the lack of sound regulatory and financial structures are major impediments to scale [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In dry regions, the lack of water again hinders electrolysis-based hydrogen production, for which direct seawater electrolysis or co-location with desalination systems are necessary solutions [

9,

13]. The lack of developed infrastructure and supply chains for hydrogen in the Global South further inhibits the viability of localized hydrogen economies.

There are other non-traditional production paths, i.e., grey, blue, and aqua hydrogen, which differ from each other in terms of carbon intensity, economics, and technology maturity level. Grey hydrogen, produced by steam methane reforming (SMR) of fossil feedstocks, currently accounts for world dominance but is high on CO₂ emissions embedded with it [

14,

15]. Blue hydrogen, by applying carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, lowers the SMR emissions but long-term sustainability remains in doubt as it is based on infrastructure build up [

6,

16]. Green hydrogen, on the other hand, is generated from entirely renewable energy and water, with resulting zero-lifecycle emissions. Although it is still more expensive, its sustainability advantages and compatibility with future global climate targets render it the most appropriate option for future energy system [

3,

7,

8]. Aqua hydrogen, the latest experimental technology involving the generation of hydrogen under non oxidizing conditions, offers a low emission option being studied [

16].

With the rising interest in the clean energy option of hydrogen, a comprehensive review of green hydrogen technologies and the potential for providing sustainable energy access to remote regions is timely and essential. The paper systematically examines the existing technology to produce green hydrogen, integration strategies for hybrid renewables, and the socio-economic, environmental consequences of deployment for energy-insecure regions. Employing the PRISMA 2020 approach [

17], 175 studies were identified with the initial scope, of which 58 peer-reviewed articles, technical reports were shortlisted for detailed analysis after applying stringent inclusion criteria.

The objectives of this review are fivefold. First, it covers the technological status of the production of green hydrogen, with PEM, AEL, and SOEC electrolyzers, along with up-and-coming technologies for direct seawater electrolysis, PEC, and bio-hydrogen systems [

9,

11,

18,

19,

20]. Second, it discusses the integration of hydrogen with hybrid energy systems with solar, wind, and hydro systems [

5,

21,

22]. Third, it examines the techno-economic performance and the environmental characteristics of these systems, highlighting the cost-drivers, emissions profiles, and reasons for water usage [

8,

12,

23]. Fourth, it outlines regional case studies, with particular emphasis on Sub-Saharan Africa, to examine the local feasibility, the policy landscape, and the potential for scaling up [

2,

4,

24]. Finally, it identifies innovations in materials science and systems engineering, with nanomaterials, high-entropy membranes, and modular systems for the deployment of hydrogen that will define future deployment options [

25,

26,

27].

With the integration of insights from the technical, economic, and policy domains, this review attempts to inform decision making for anyone interested in leveraging green hydrogen as an accelerant of inclusive, resilient, and climate compatible energy transitions for off grid and remote locations.

2. Materials and Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 protocol [

28] was applied. Studies were retrieved from Scopus, Web of Science, and IEEE Xplore databases using search terms: “green hydrogen,” “electrolysis,” “hybrid renewable,” “remote energy,” “Africa,” and “techno-economic assessment.” Inclusion was limited to peer-reviewed publications and reputable industry reports from 2010–2025.

A total of 175 studies were identified; after removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 57 remained. Following full-text assessment, 57 studies met the inclusion criteria.

3. Hydrogen Production Technologies

Production technologies for hydrogen are usually defined by the source of energy, and carbon intensity, with often related color coding. The classification reflects the environmental integrity and maturity of the technology, key features for the sustainable energy vision, especially for remote and off-grid applications where decarbonisation andresource efficiency are necessary.

Most commonly produced today is grey hydrogen, generated predominantly by steam methane reforming (SMR) of natural gas. The technology for this is established, with good infrastructure, low production costs, and high capacity scalability, but it is the most carbon-intensive method to produce it, with approximately 9–12 kg of CO₂ being generated per kilogram of produced hydrogen, therefore being the largest contributor to worldwide greenhouse (GHG) emissions [

10,

27].

Blue hydrogen aims to decouple the emissions of grey hydrogen by applying carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies to the SMR process. Blue hydrogen presents moderate net CO₂ emission reductions while maintaining the maturity, scalability, and low cost of grey hydrogen [

24]. Its environmental success, however, relies heavily on the success and longevity of CO₂ capture, and it remains vulnerable to upstream methane leakage during natural gas extraction and transportation [

29].

Green hydrogen is produced by renewable energy driven water electrolysis, usually solar or wind, or other renewable energy sources. It emits no direct GHG emissions where it is produced and is considered the most sustainable solution. Green hydrogen has specific opportunities for off-grid situations, where renewable energy or water is within easy reach, enhancing energy self-sufficiency [

12,

23]. Though it has many virtues, its technology is not yet as mature as the grey or blue version, with a higher levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) of €3.5–6.0/kg [

10]. That being said, subsequent technological advancements, together with falling renewable energy costs, will probably make green hydrogen more equivalent to other alternatives by 2050. That it depends on rare, expensive materials, such as iridium and platinum, for the proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers, presents issues for long-term circularity and sustainability of resources [

13,

15].

Aqua hydrogen is a new generation of non oxidizing technologies for the production of hydrogen, including plasma pyrolysis and photonic water splitting technology. The technologies hold the promise of being able to abolish the emission of CO₂ altogether without the exploitation of strategic raw materials. Aqua hydrogen has significant potential for low-footprint, decentralized hydrogen generation, suitable for future off-grid applications. The technologies, however, are still in the nascent stage of R&D, with low commercial maturity and small-scale production capacity [

12,

26].

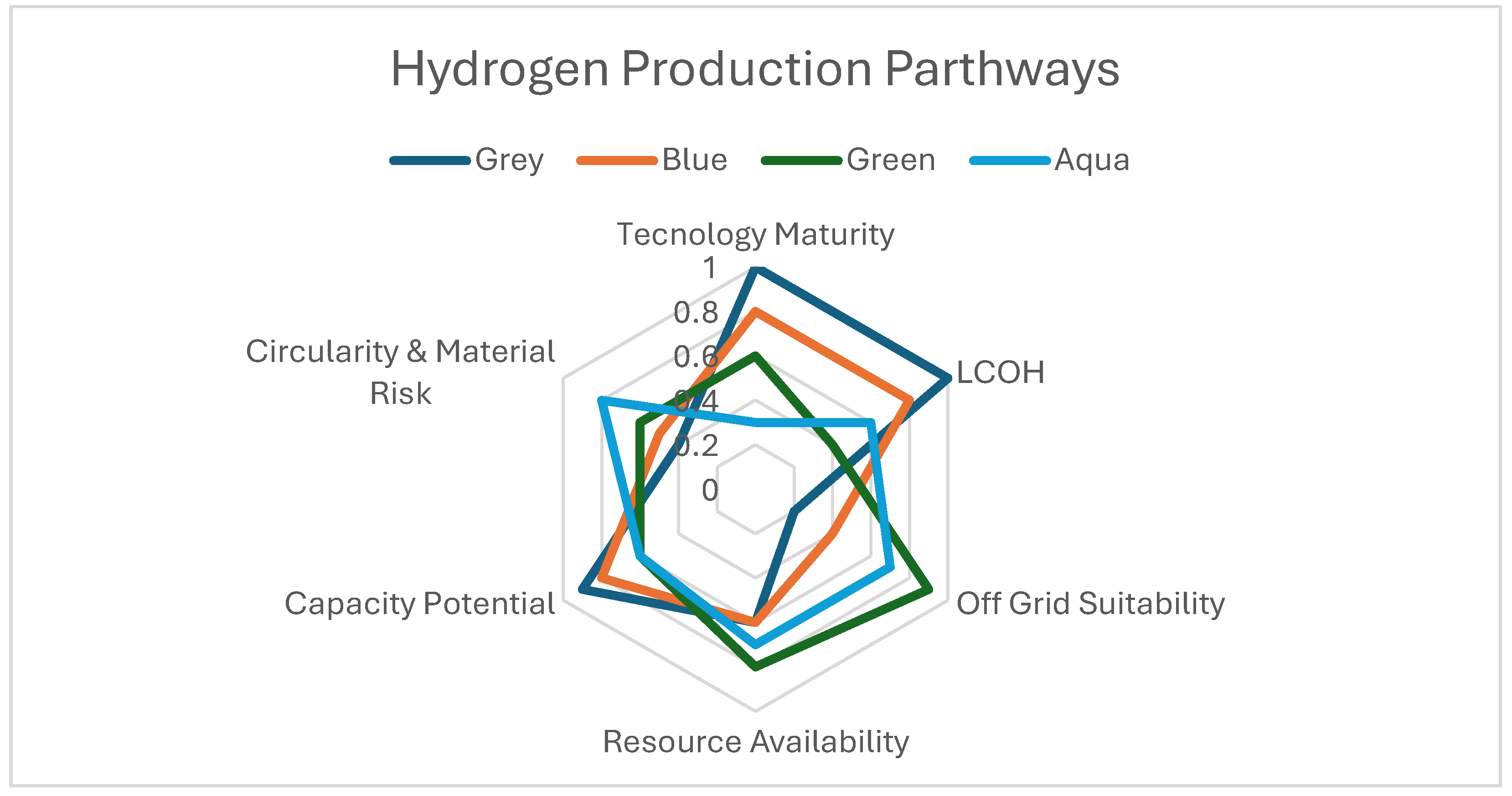

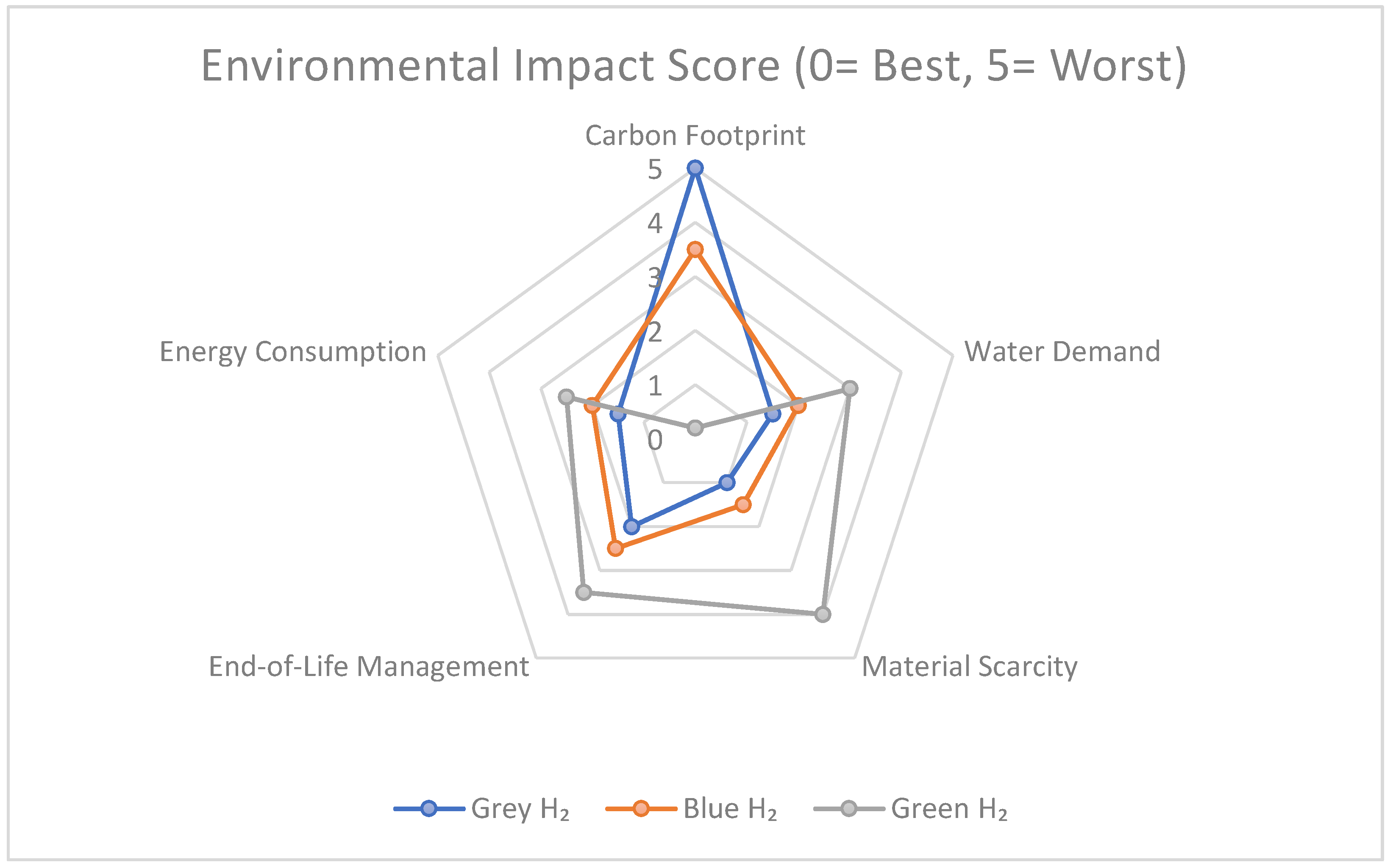

Comparing the grey, blue, green, and aqua hydrogen technologies on a radar chart (

Figure 1), the chart illustrates how the technologies perform in the following six indicators: technology maturity, levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH), off-grid suitability, availability of resources, potential capacity, and circularity and material risk. Grey and blue hydrogen do best on maturity and capacity but worst on sustainability indicators. Green hydrogen has a fairly balanced profile with strengths on off-grid flexibility and environmental alignment but weaknesses on costs and material utilization. Aqua hydrogen excels on sustainability indicators but lags on maturity and scale because the technology remains immature with the level of development.

4. Electrolysis Technologies for Green Hydrogen Production.

Electrolysis allows the generation of green hydrogen by breaking down the water to produce hydrogen and oxygen with the help of electricity. It is carbon-free if it is run by renewable energy sources. It has a big impact on the performance, cost, and applicability for off-grid applications of the system technology employed.

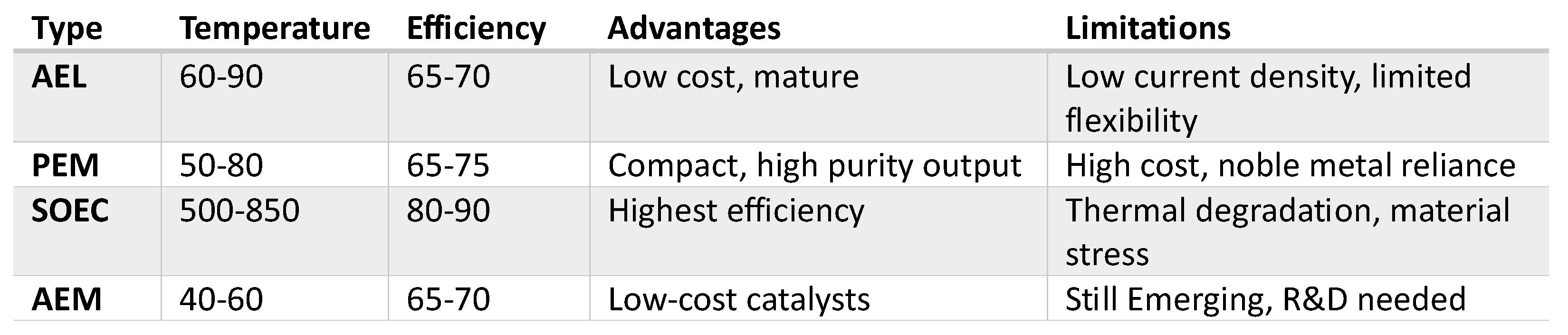

Four major electrolysis technologies being researched and commercially implemented are:

Alkaline Electrolyzers (AEL): Most mature and developed among these categories are the AELs, with the characteristic of the usage of a liquid alkaline electrolyte (commonly KOH or NaOH) and the provision of low cost and operating strength. However, low operating current density, together with slow dynamics for these electrolyzers’ response, hinder integration with intermittent renewable energy sources [

10,

30].

PEM Electrolyzers: PEM electrolyzers possess high efficiency, high current density, quick start up, and high purity gaseous hydrogen output. PEM electrolyzers are applicable for variable renewable energy inputs. The disadvantage of PEM electrolisers is dependence on expensive rare meterials such as platinum and iridium, which leads to shortage issues and supply constraints [

13,

31,

32].

Solid Oxide Electrolysis Cells: SOECs rely heavyly on heat and electricity to generate hydrogen with high efficiency at high temperatures, the temperature ranges from 500 to 850 °C. Performance of SOECs is high when combined with concentrated solar power or industrial waste heat sources, as this decreases the electrical energy needed for electrolysis. Common use has been limited by challenges including material degradation from extended high temperature operation and the complexities associated with thermal management systems [

33,

34].

Anion Exchange Membrane (AEM) Electrolyzers: The AEM electrolyzers incorporate aspects of the AEL alongside the PEM technologies. The AEM has non-noble metal catalysts, presenting a potential pathway for reducing costs. Though not yet fully developed, the systems of AEM possess potential for future deployment on a large scale [

13,

33,

35,

36].

Table 1, presents the key characteristics of each electrolyzer types as compare to others.

5. Renewable Integration and Hybrid Systems

Integration of green hydrogen generation with renewable energy technologies, such as solar photovoltaic (PV) panels and wind systems, is an important strategy for obtaining decarbonized, dispatchable energy for both grid-scale and off-grid applications. By synchronizing variable renewable energy (VRE) with electrolyzers, hydrogen can be used for long-duration energy storage, enabling the buffering of the supply-demand gaps, as well as mitigating the intermittency of the renewables.

Many case studies confirm the efficiency and reliability of hybrid systems with solar-powered proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers, mainly for high-solar irradiation regions, e.g., regions of the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa [

4,

37,

38,

39,

40]. The case studies stress the importance of adapting the operation of the electrolyzers to peak solar irradiation for the purpose of increasing the output of hydrogen as well as the efficiency of the system.

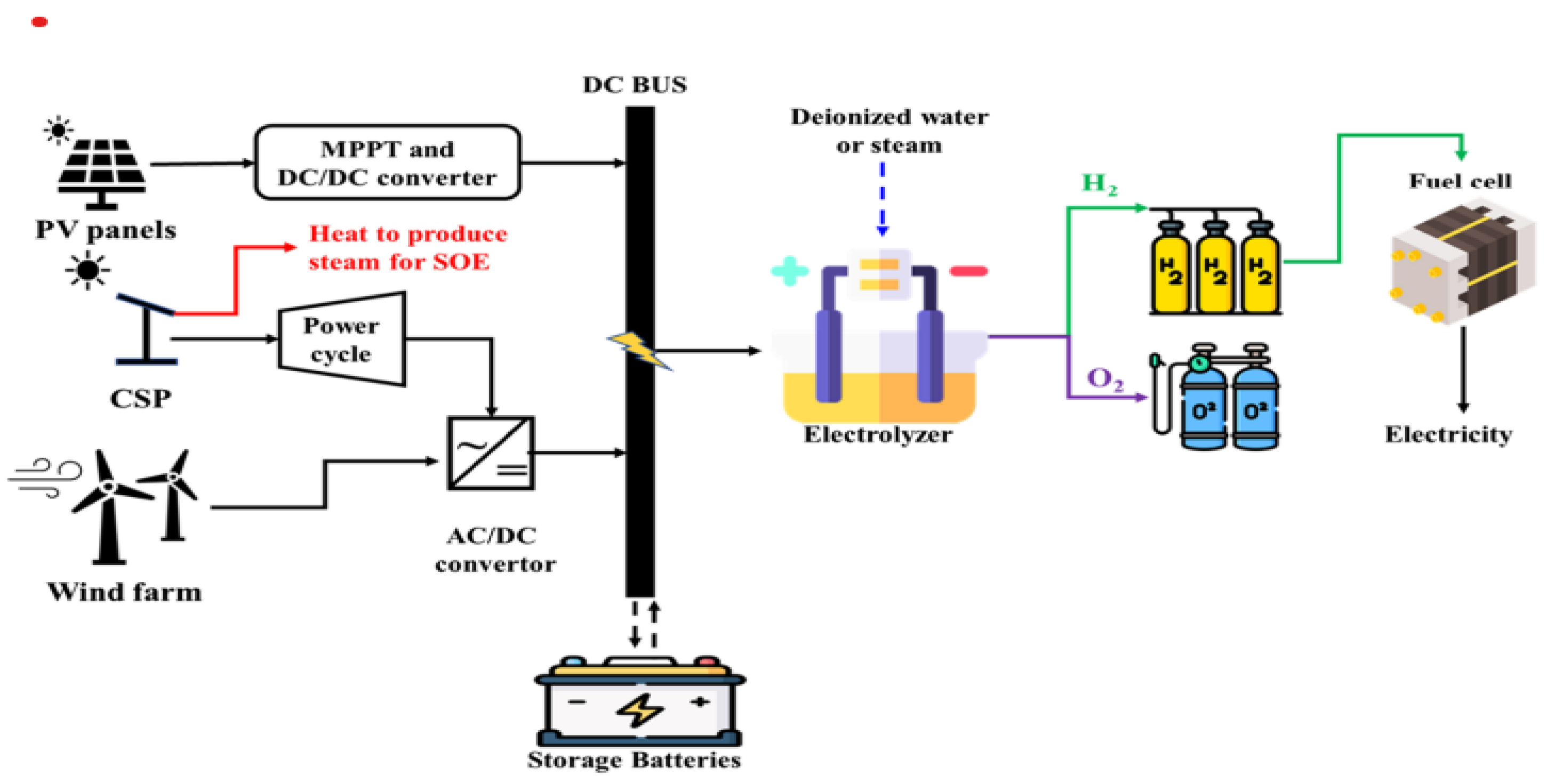

A representative configuration of such a hybrid system is illustrated in

Figure 2, comprising PV arrays, CSP, Wind generator, PEM electrolyzers, hydrogen storage tanks, fuel cell and optional battery storage. The figure demonstrates the flow of energy and hydrogen throughout the system components.

An exemplary setup of the hybrid system is shown in

Figure 2, consisting of PV panels, CSP, Wind turbine, PEM electrolysers, storage tanks for storing hydrogen, fuel cell, and optional storage batteries. The diagram in

Figure 2, demonstrate the energy and hydrogen flows within the parts of the system.

The improvement of the system design is very important for reducing energy loss and maximixing electrolyzers efficiency. The improvement should focus on the sizing of the PV capacity, storage, and electrolyzer configurations. Benghanem et al. [

18] and Sarker et al. [

41] studies indicate that inefficient sizing results in underutilized assets or loss of excess hydrogen, both of which negate economic viability [

42]. In addition, adding battery storage can enhance the dynamic response to variable solar or wind inputs and allow for short-term power stability, while solid oxide electrolysis cells (SOECs) possess high efficiency and lend themselves to thermal integration with industrial or solar thermal waste heat sources [

22,

34].

Such renewable hydrogen hybrid systems will be the most viable for off-grid or weak-grid regions, where decentralized energy delivery or fuel flexibility is the overriding need. Modular, scalable, and weather-resistant system configurations will be critical to enhancing energy access within energy-scarce regions while supporting global decarbonization goals [

43,

44].

6. Techno-Economic and Environmental Assessments.

Although it has the potential to be a clean energy carrier, the large-scale application of green hydrogen is currently hampered by techno-economic as well as environmental constraints. The Levelized Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH) is one of the important indicators in the economic viability assessment of hydrogen, defined as the lifetime system cost of producing a kilogram of hydrogen, including the capital, operating, and energy input costs.

Currently, green hydrogen is less competitive compared to grey hydrogen, which is produced from natural gas via steam methane reforming (SMR) without carbon capture, and blue hydrogen, which incorporates carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies. projections from PwC [

45], Terlouw et al. [

12] and [

46] indicate a notable decrease in LCOH for green hydrogen over the coming decades due to several interrelated factors such as decreasing costs of renewable electricity, especially from solar photovoltaic and onshore wind sources, the amount of scale and experiential learning in the manufacturing and installation of electrolyzers, and reduced operational and delivery costs because of improved storage and distribution systems.

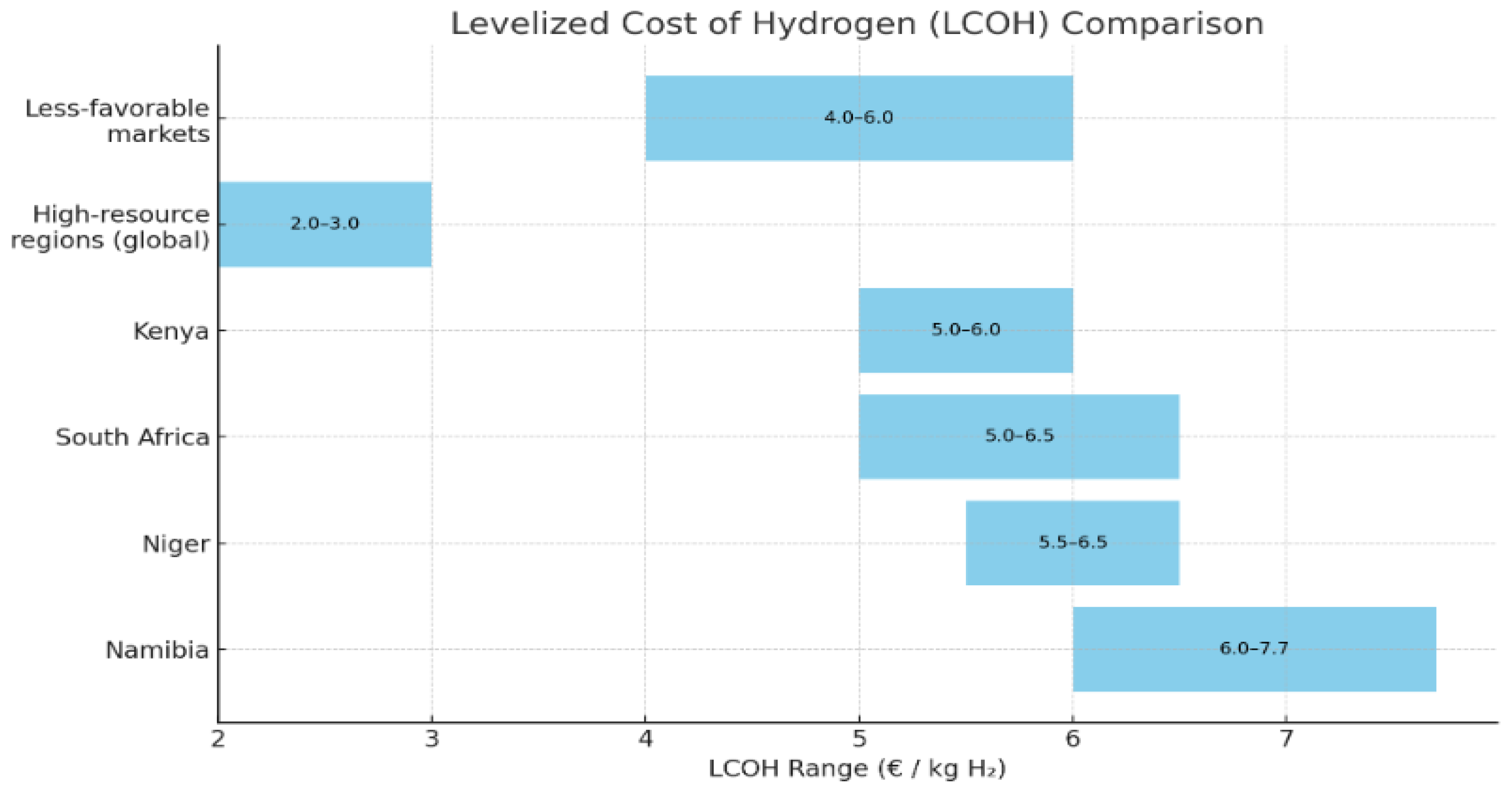

In optimal locations characterized by high renewable capacity considerations and robust policies, the levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) for green hydrogen is projected to decrease to €1.0–1.5/kg by 2050, potentially matching the cost of hydrogen generated from fossil sources. In the current environment, the LCOH, however, remains highly variable, between €4.0–6.0/kg for the worst market scenarios to the level of €2.0–3.0/kg for the best-resource regions. The Levelized Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH) Comparison is shown by the

Figure 3.

Namibia has the highest current LCOH range (€6.0–7.7/kg), reflecting its early-stage infrastructure but high potential due to abundant solar resources.

Niger, South Africa, and Kenya all fall in a mid-range of €5.0–6.5/kg, making them relatively more competitive in the African context.

High-resource areas of the world such as Chile or Morocco exhibit significantly lower LCOH (€2.0–3.0/kg) values because the conditions and infrastructure are optimized.

Less favorable global markets remain with high costs (€4.0–6.0/kg), revealing the challenge for the application of green hydrogen without favorable renewable infrastructure or economic stimulus.

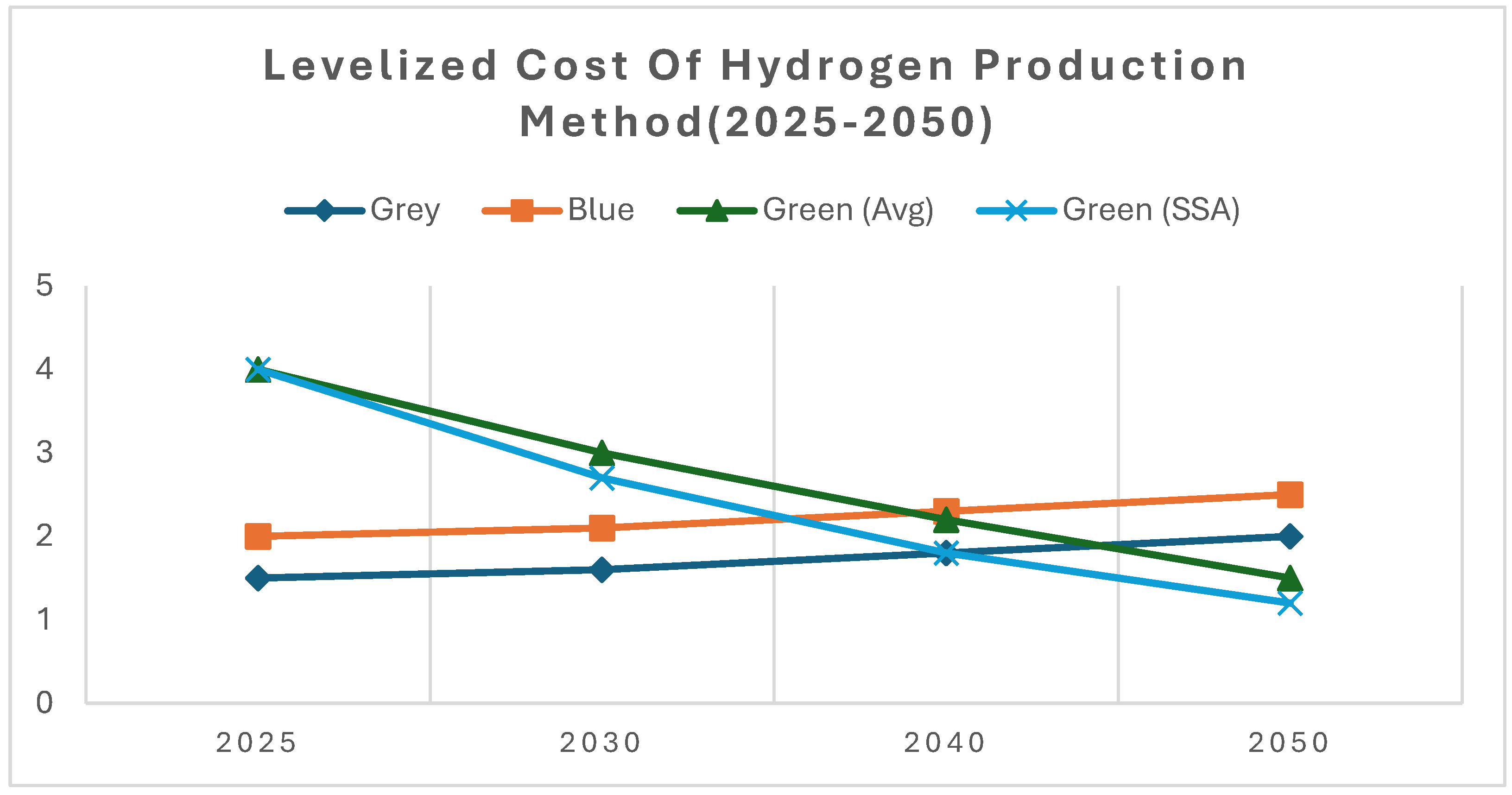

Figure 4, shows the projected LCOH evolution for grey, blue, and green hydrogen scenarios through 2050. These results were obtained from varies LCA studies [

12,

23,

27,

47].

From an environmental standpoint, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as a vital tool to quantify the environmental performance of various hydrogen production routes. Main findings of the latest LCA studies [

12,

23,

27], are as follows:

Green hydrogen has the lowest carbon intensity, typically near zero when produced with fully renewable electricity;

Water demand is a critical consideration, particularly in dry regions where desalination is needed, increasing energy consumption and system complexity;

Scarce materials: The need for platinum group metals (PGMs) such as iridium and platinum in PEM electrolyzers, and rare earths for related power electronics, is increasing;

End-of-life management of system components, such as membrane recycling and safe disposal of catalysts, remains under-addressed in many studies.

Figure 5, radar shows the comparison of environmental aspects of grey, blue, and green hydrogen production technologies based on recent Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies. This radar uses normalized impact scores (0 = best, 5 = worst).

7. Regional Feasibility in Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has tremendous potential for green hydrogen development because it has vast renewable energy resources, increasing energy demand, and rising interest in low-carbon industrialization. Most SSA countries possess high solar irradiation, stable winds, and availability of under used lands, making them prime targets for scalable renewable energy-based electrolysis projects. Green hydrogen deployment feasibility, though, differs from country to country, with factors relating to infrastructure readiness, access to water, policies, and investment regimes playing a role.

There are some African nations starting to market themselves as future exports of green hydrogen as well as future industrial users. The early frontrunners were Namibia and South Africa, starting national plans and pilot projects. Namibia’s Green Hydrogen Council and collaborative ventures with Germany target the generation and export of the fuel based on desert solar energy and desalinated sea water [

24]. South Africa, with renewable potential and in industrial base, has unveiled the Hydrogen Society Roadmap, as well as Northeren Cape and Western Cape projects [

4].

Other countries, such as Mauritania, Morocco, and Egypt, are also developing green hydrogen clusters, driven by European demand and strategic port access. Within Sub-Saharan Africa specifically, nations like Kenya, Ethiopia, and Angola are exploring feasibility studies and cross border green energy trade [

2]. Despite this momentum, challenges remain particularly in financing, skilled workforce development, water re-source management, and policy coordination.

The regional potential for green hydrogen in SSA is significant, particularly when renewable resources, political commitment, and international collaboration are in harmony. Strategic investments and the enhancement of capabilities could empower the region to sustainably fulfill its domestic energy requirements while also engaging competitively in the developing global hydrogen market.

Figure 6, present the comparative bar chart showing the regional feasibility of green hydrogen development in selected African countries. The indicators include renewable energy potential, water access or strategy, policy presence, and international partnerships each normalized scale between 0 and 1.

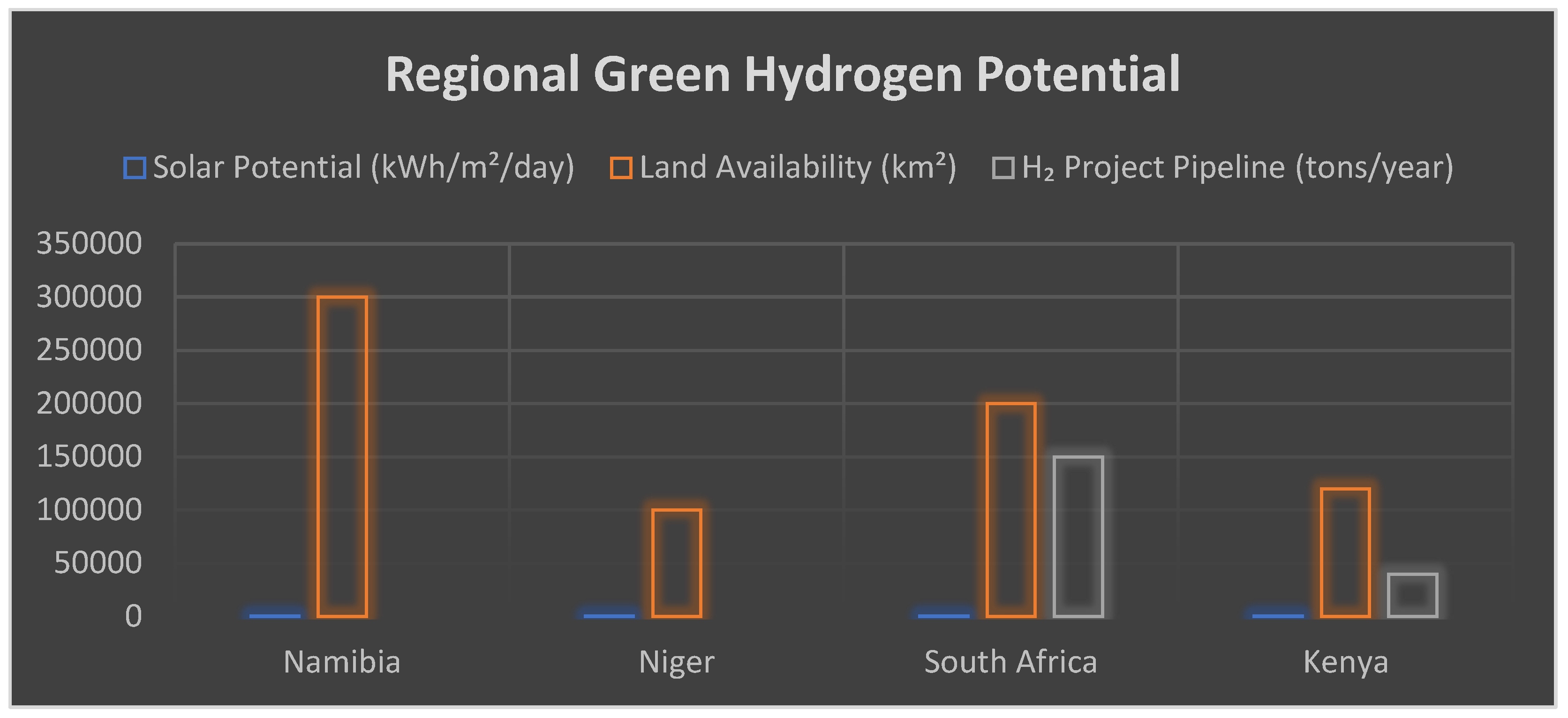

Figure 7, illustrates the green hydrogen development potential in leading African Countries and progress of green hydrogen initiatives in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Namibia is identified as the most ambitious participant, with an expected electrolysis capacity of 300,000 MW, positioning it as the biggest in the region. This is driven by strong solar irradiance, vast arid land availability, and firm international partnerships, particularly with Germany, through the Hyphen Hydrogen Energy initiative [

4]. The nation has a high Levelized Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH) of between €6.0–7.7/kg, but enjoys long-term scalability and export opportunities underpinned by sound policy alignment and foreign funding [

2,

4].

South Africa follows closely, with a planned 200,000 MW capacity and an estimated LCOH of €5.0–6.5/kg. This range is good because there are local platinum sources for PEM electrolysis, there is already an industrial base, and there are strategic plans like the Hydrogen Society plan. Its project maturity is relatively advanced, with 150,000 MW already under active development [

4,

24].

Although the Levelized Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH) is relatively extreme ranging from €6.0 to €7.7 per kilogram, the nation enjoys significant long-term scalability and export potential, bolstered by strong policy alignment and foreign investment [

2,

4].

South Africa is positioned next, with a proposed capacity of 200,000 MW and a projected levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) ranging from €5.0 to €6.5 per kilogram. This range, although not as low as in certain developed hydrogen markets, is promising due to local platinum resources for PEM electrolysis, an existing industrial base, and strategic initiatives such as the Hydrogen Society Roadmap. Its project maturity is relatively advanced, with 150,000 MW already under active development [

4,

24].

Niger, though less advanced in terms of infrastructure, demonstrates growing interest in green hydrogen, especially for energy access in rural areas. Its LCOH range (€5.5–6.5/kg) is competitive, though limited by water scarcity and transmission limitations. The feasibility-phase capacity of 80,000 MW suggests moderate potential, particularly if international support and hybrid PV-electrolysis integration improve [

9,

24].

Kenya is exploring geothermal powered hydrogen, a unique approach in the region. Although its planned capacity is more modest (120,000 MW, with only 40,000 MW in development), the LCOH range of €5.0–6.0/kg reflects strong renewable resource availability and potential cost efficiency. Its pilot projects around the Olkaria geothermal site could position the country as a niche player in low-carbon hydrogen production [

2,

12,

24].

8. Emerging Technologies and Materials

New technologies for emerging hydrogen production along with new materials will greatly enhance the possibility of green hydrogen, particularly for off-grid decarbonization applications. Solar energy is converted to hydrogen via direct water splitting, called the photoelectrochemical (PEC) process, and is attracting attention for small-scale, decentralized operation. The need for fresh feedstock is eliminated with direct seawater electrolysis, essential for desert states and island nations [

9,

20,

48].

Nanotechnology has been very important in making electrodes work better. TiO2, graphene, and metal organic frameworks (MOFs) improve the performance of catalysts by making them more effective in absorbing light. Carbon nanostructures and doped semiconductors with values higher than 10% have made it possible to convert solar energy into hydrogen energy [

27,

49,

50].

Aqua hydrogen, as a brand-new idea, exploits the fossil fuels but gets rid of the CO2 emissions by applying high-tech chemical looping or new cracking processes. Though not entirely renewable, it can be implemented as a low-emission transition approach [

16,

51].

Designs of electrolyzers are also being transformed by material innovations. Solid-state membranes and high-entropy alloys (HEAs) are being researched to decrease the dependency on platinum group metals, enhance durability, as well as efficiency. Innovations in membranes, such as anion exchange polymers with enhanced conductivity and chemical stability, hold the key to scale up of AEM electrolyzers [

26,

36,

52].

These innovations not only add to lowering the levelized cost of hydrogen but also increase the flexibility of the systems for hydrogen usage in decentralized, off-grid, or water scarce areas [

53,

54].

9. Policy, Financing, and Social Considerations

Green technologies scalability and diffusion depend not just on technological maturity and financial sustainability but also on favorable policy settings, funding instruments, and socio-political structures. For the release of large scale deployment, government administrations need to introduce straightforward, long-term hydrogen policies with national roadmaps, regulative settings, as well as subsidies for both demand and supply side operations. Mainstays are incentives for electrolyzer manufacturing, infrastructure development funding as well as the setup of special hydrogen corridors to connect the production centers with the consumption points [

6,

29,

55].

Working together across borders is essential when it comes to harmonizing certification systems. Such collaboration streamlines trade and makes it easier to exchange successful approaches. International organizations such as the African Development Bank and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) make a vital contribution by brokering global cooperation which is needed in order to translate good ideas into agreed standards. They also help secure funding for green hydrogen projects in emerging economies [

35].

Funding green hydrogen projects has some big challenges, They come with big upfront costs, long payback periods and technology risks which can scare off private investors. Combining financial tools like risk guarantees, green bonds and public coinvestment can help reduce the risks of early stage projects and bring in big investors [

56]. As markets mature we will see more private sector involvement especially as demand for decarbonised fuels grows in tough industries like steel, cement and aviation.

Hydrogen projects must adopt community planning that engages residents proactively in order to be successful. This entails engagement with the indigenous people, allowing them land access for all uses and tackling the issue of emissions, water and safety. Programs of capacity building must be set up by training host country workforces on operating electrolyzers, installing systems and maintenance. This will create green jobs and increase the overall capacity of the region [

57].

Social acceptance may further be enhanced by transparent communication among stakeholders and citizen information campaigns about the benefits and risks of the hydrogen technologies. Equity and justice values must inform every deployment strategy to avoid the rerunning of energy exclusion history and environmental injustice.

10. Discussion

This review examines the potential of green hydrogen in addressing shortages of energy and decarbonization challenges, particularly in remote and off-grid regions. Green hydrogen technologies are being developed. Their integration with various renewable energy sources could create strong and flexible energy networks. A study comparing production methods shows a significant shift toward sustainability. Grey hydrogen relies on fossil fuels and has high emissions, while green hydrogen is fully renewable and produces almost no emissions. While grey and blue hydrogen have the advantage of existing infrastructure and lower production costs, their future is somewhat limited due to carbon emissions and dependence on fossil fuel supply chains. On the other hand, green hydrogen aligns more closely with net zero objectives. The catch? Currently it is not economical due to high initial costs, a supply chain that is still in its infancy, and a need for scarce materials.

Electrolysis technologies come with a variety of tradeoffs that can impact how feasible they are to deploy across different geographies and applications. Alkaline and PEM electrolyzers are the most commercially developed to date, but PEM, by being based on critical metals such as iridium and platinum, is a source of concerns related to scalability and circularity. Solid oxide electrolyzers provide high efficiency but need thermal integration and do not lend themselves as much to intermittent renewable energy inputs. The anion exchange membrane electrolyzers is a promising frontier, with the low-cost potential of the alkaline systems and the dynamic performance of the PEM, but it is still in the initial development phases.

Hybrid renewable hydrogen systems constitute an attractive solution to the intermittency issues of solar and wind energy. The literature surveyed testifies to the value of optimal design of the overall system, especially for the capacity of PV, the design of the electrolyzer stack, and storage of hydrogen to prevent curtailment and achieve high utilization factors. The integration of the generation of hydrogen with batteries or thermal integration (e.g., CSP or industrial waste heat) increases the operational stability and dispatchability, thus making the green hydrogen more appealing for remote or weak-grid areas. The integration with fuel cells and modular storage further increases the flexibility of the system as well as long-term energy autonomy.

From a techno-economic perspective, green hydrogen is not yet competitive with grey or blue hydrogen for most market applications, with current levelized costs of €3.5 to €6.0 per kilogram. Scenarios, however, indicate the potential for green hydrogen to become competitive by 2050 for high-resource regions with further reduction in the renewable electricity generation costs, scale advantage for the deployment of electrolysers for manufacturing, and market maturity by policies. Most importantly, these scenarios depend on favorable policies, mature infrastructure, and concurrent investments across both demand and supply side development. Life cycle environmental assessment for green hydrogen comes out in support of the low emissions outcome but raises an issue with the freshwater usage within electrolysis, particularly within dry regions. In these regions, emerging technologies, for instance, direct seawater electrolysis, as well as systems with integration with seawater desalination, could prove essential.

Sub-Saharan Africa is strategically placed to perform a significant role in the emerging hydrogen economy, with countries like South Africa, Namibia, and Kenya leading through national roadmaps, pilot initiatives, and global alliances. These initiatives are made possible thanks to great solar and wind resources, strong political support, and a growing emphasis on low carbon industrialization. Still, perennial challenges remaining include scant hydrogen infrastructure, source constraints on water, gaps in funding, as well as lack of technical capacity. Merging these will require collaborative action across governments, development banks, academia, as well as private sector players. Inclusive settings for policies, as well as capacity-development initiatives, will be required to ensure the development of hydrogen not only contributes to climate targets but also to equitable socio-economic benefits.

New technologies for the generation of hydrogen, for example, the photoelectrochemical dissociation of water, or the aqua hydrogen, will tend to enhance the efficiency, the size, and the environmental applicability of the systems for the generation of green hydrogen. Though most of these technologies remain within first phases of development, there is promise for them to be applied for decentralized, water-scarce, or infrastructure-restricted applications. As the world for hydrogen keeps evolving, the ability to innovate and to introduce innovations will be necessary to make major impacts on off grid applications. This journal emphasizes that green hydrogen is no panacea, but it is fundamental in driving sustainable transitions of energy, especially in rural and disadvantaged communities. Though perhaps not solving all energy problems, its value in driving substantive transitions of such a society is important and effective. Meeting this objective would necessitate long term innovation, integrated infrastructure planning, equitable financing systems, and coordinated policy alignment at the local, national, and global levels.

11. Conclusion

Green hydrogen is increasingly seen as a vital player in achieving sustainable energy access, especially in remote, off-grid areas where traditional energy systems fall short or depend on carbon-based sources. This review indicates that despite significant techno-economic and infrastructure challenges associated with green hydrogen technologies, they offer distinct benefits in terms of energy independence, long-term storage, and the achievement of environmental goals. Renewable electricity-based green hydrogen represents the most environmentally sustainable method for hydrogen production, exhibiting minimal emissions throughout its entire life cycle. The comparison of the technology of electrolysis highlights the possibility of technological diversification, with presently dominant deployment by AEL, followed by PEM electrolyzers, with long-term efficiency and cost-reduction potential by SOEC systems, as well as by AEM systems.

Green hydrogen integration with hybrid renewable systems addresses the problem of solar and wind energy intermittency efficiently, enhances the system resilience, and allows for decarbonized energy supply for remote areas. Techno-economic projections indicate the potential for cost competitiveness for green hydrogen by 2050, particularly for areas with high renewable energy potential and good regulation policies for the sector. Environmental assessments show that carbon footprints are low but water usage, material circularity and end of life systems need to be addressed. In Sub-Saharan Africa there is an opportunity to benefit from and contribute to the global hydrogen economy if investments, infrastructure development and build institutional capacity is prioritized.

Green hydrogen is not just a clean fuel but a strategic pathway for energy justice, industrialization, and climate resilience. The successful application in remote, off-grid locations will require an integrated approach involving technological innovation, inclusive policy making, global cooperation, and long-term financial dedication.

Author Contributions

Nkanyiso Msweli.; writing-review, Nnachi Gideon Ude and Coneth Graham Richards.; supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review is funded by Tshwane University of Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they possess no identifiable competing financial interests or personal ties that may have seemingly influenced the work presented in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AEL |

Alkaline Electrolyzer |

| AEM |

Anion Exchange Membrane |

| CCS |

Carbon Capture and Storage |

| CSP |

Concentrated Solar Power |

| GHG |

Greenhouse Gas |

| HEA |

High Entropy Alloy |

| IRR |

Internal Rate of Return |

| LCA |

Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCOH |

Levelized Cost of Hydrogen |

| MOF |

Metal Organic Framework |

| PEM |

Proton Exchange Membrane |

| PEC |

Photoelectrochemical |

| PGMs |

Platinum Group Metals |

| PV |

Photovoltaic |

| R&D |

Research and Development |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goal |

| SMR |

Steam Methane Reforming |

| SOEC |

Solid Oxide Electrolysis Cell |

| SSA |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

| VRE |

Variable Renewable Energy |

References

- Kourougianni, F.; Arsalis, A.; Olympios, A.V.; Yiasoumas, G.; Konstantinou, C.; Papanastasiou, P.; Georghiou, G.E. A comprehensive review of green hydrogen energy systems. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 182, 114664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ude, N.G.; Graham, R.C.; Yskandar, H. A review of current status of green hydrogen economy in Sub-Saharan Africa. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 123456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, R.; Adhikari, N. A comprehensive review on the role of hydrogen in renewable energy systems. Re-newable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 157, 112033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, R. Green hydrogen production potential in West Africa Case of Niger. Renewable Energy 2022, 196, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.; Ramu, S.K.; Devarajan, G.; Vairavasundaram, I.; Vairavasundaram, S. A review on hydrogen-based hybrid microgrid system: Topologies for hydrogen energy storage, integration, and energy management with solar and wind energy. Energies 2023, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noussan, M.; Raimondi, P.P.; Scita, R.; Hafner, M. The Role of Green and Blue Hydrogen in the Energy Transition A Technological and Geopolitical Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 13, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, R.; Lv, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhou, H.; Xu, C. Green hydrogen: A promising way to the carbon-free society. Chinese J. Chem. Eng 2022, 43, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, R.A.; Mohamed, M.; Farag, H.E.Z.; El-Saadany, E.F. Green hydrogen production plants: A tech-no-economic review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 186, 113382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meharban, F. Harnessing direct seawater electrolysis for a sustainable offshore hydrogen future: A critical review and perspective. Applied Energy 2025, 384, 125468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.S.; Jalil, A.A.; Rajendran, S.; Khusnun, N.F.; Bahari, M.B.; Johari, A.; Kamaruddin, M.J.; Ismail, M. Recent review and evaluation of green hydrogen production via water electrolysis for a sustainable and clean energy society. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 420–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, D. The future of hydrogen energy: Bio-hydrogen production technology. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 33677–33698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlouw, T.; Bauer, C.; McKenna, R.; Mazzotti, M. Large-scale hydrogen production via water electrolysis: a techno-economic and environmental assessment. Energy Environ. Sci 2022, 15, 2990–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, M.; Megahed, T.F.; Ookawara, S.; Hassan, H. A review of water electrolysis–based systems for hydrogen production using hybrid/solar/wind energy systems. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2022, 25, 1663–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megía, P.J.; Vizcaíno, A.J.; Calles, J.A.; Carrero, A. Hydrogen Production Technologies: From Fossil Fuels toward Renewable Sources. A Mini Review. Energy & Fuels 2021, 35, 16403–16415. [Google Scholar]

- El-Emam, R.S.; Özcan, H. Comprehensive review on the techno-economics of sustainable large-scale clean hydrogen production. J. Clean. Prod 2019, 220, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Wang, K.; Vredenburg, H. Insights into low-carbon hydrogen production methods: Green, blue and aqua hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 21261–21273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Y.G.C.; Santaella, J.R.B.; Susa, D.A.H. Green hydrogen: a state-of-the-art review of generation technologies for the decarbonisation of the energy sector. Ingeniería y Competitividad 26, 0, 2024.

- Benghanem, M.; Mellit, A.; Almohamadi, H.; Haddad, S.; Chettibi, N.; Alanazi, A.M.; Dasalla, D.; Alzahrani, A. Hydrogen production methods based on solar and wind energy: A review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.K.; Chakraborty, S.; Elangovan, D. A brief review of hydrogen production methods and their challenges. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabgan, W. A bibliometric examination and state-of-the-art overview of hydrogen generation from photoelec-trochemical water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 358–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnabuife, S.G.; Hamzat, A.K.; Whidborne, J.; Kuang, B.; Jenkins, K.W. Integration of renewable energy sources in tandem with electrolysis: A technology review for green hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 107, 218–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastropasqua, L.; Pecenati, I.; Giostri, A.; Campanari, S. Solar hydrogen production: Techno-economic analysis of a parabolic dish-supported high-temperature electrolysis system. Appl. Energy 2020, 261, 114392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammi, Z.; Labjar, N.; Dalimi, M.; Hamdouni, Y.E.; Lotfi, E.M.; El Hajjaji, S. Green hydrogen: A holistic review covering life cycle assessment, environmental impacts, and color analysis. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 182, 113882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnachi, G.U.; Richards, C.G.; Hamam, Y. , “Appraising the benefits of investing in green hydrogen in Sub-Saharan Africa’s energy mix,” in in Proc. 2025 33rd Southern African Universities Power Engineering Conf. (SAUPEC), 2025.

- Samat, N.A.S.A.; Goh, P.S.; Lau, W.J.; Guo, Q.; Ismail, A.F.; Wong, K.C. Green hydrogen revolution: Sus-tainable hydrogen separation using hydrogen-selective nanocomposite membrane technology. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 22032–22056. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, G.; Li, T.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Niyogi, M.; Cariaga, K.; Oses, C. High entropy powering green energy: hydrogen, batteries, electronics, and catalysis. npj Comput. Mater 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.S.; Shen, S.; Guo, L. Nanomaterials for renewable hydrogen production, storage and utilization. Progress in Natural Science: Materials International 2012, 22, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Y.G.C.; Santaella, J.R.B.; Susa, D.A.H. Green hydrogen: a state-of-the-art review of generation technologies for the decarbonisation of the energy sector. Ingeniería y Competitividad.

- Oliveira, A.M.; Beswick, R.R.; Yan, Y. A Green Hydrogen Economy for a Renewable Energy Society. Joule 2021, 5, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I.; Acar, C. Review and evaluation of hydrogen production methods for better sustainability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 11094–11111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpino, F.; Canale, C.; Cortellessa, G.; Dell’Isola, M.; Ficco, G.; Grossi, G.; Moretti, L. Green hydrogen for energy storage and natural gas system decarbonization: An Italian case study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Scott, K. The effects of ionomer content on PEM water electrolyser membrane electrode assembly performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 12029–12037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.S.K.A.H. An overview of water electrolysis technologies for green hydrogen production. Energy Rep 2022, 13793–13813. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, M.K.; Hassan, Q.; Tabar, V.S.; Tohidi, S.; Jaszczur, M.; Abdulrahman, I.S.; Salman, H.M. Techno-economic analysis for clean hydrogen production using solar energy under varied climate conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 2929–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzmann, D.; Heinrichs, H.; Lippkau, F.; Addanki, T.; Winkler, C.; Buchenberg, P.; Hamacher, T.; Blesl, M.; Linßen, J.; Stolten, D. Green hydrogen cost-potentials for global trade. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 25803–25824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidas, L.; Castro, R. Recent Developments on Hydrogen Production Technologies: State-of-the-Art Review with a Focus on Green-Electrolysis. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, T.; Kelly, N.A. Predicting efficiency of solar powered hydrogen generation using photovolta-ic-electrolysis devices. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 9001–9010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, M.; Han, D.S. Efficient solar-powered PEM electrolysis for sustainable hydrogen production: an integrated approach. Emergent Materials 2024, 7, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidouri, D.; Marouani, R.; Cherif, A. Modeling and Simulation of a Renewable Energy PV/PEM with Green Hydrogen Storage. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 12543–12548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnabuife, S.G.; Quainoo, K.A.; Hamzat, A.K.; Darko, C.K.; Agyemang, C.K. Innovative Strategies for Combining Solar and Wind Energy with Green Hydrogen Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.K.; Azad, A.K.; Rasul, M.G.; Doppalapudi, A.T. Prospect of green hydrogen generation from hybrid renewable energy sources: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 183, 113857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabode, O.E.; Ajewole, T.O.; Okakwu, I.K.; Alayande, A.S.; Akinyele, D.O. Hybrid power systems for off-grid locations: A comprehensive review of design technologies, applications and future trends. Scientific African 2021, 13, 00884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhao, P.; Niu, M.; Maddy, J. The survey of key technologies in hydrogen energy storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 14535–14552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnabuife, S.G.; Hamzat, A.K.; Whidborne, J.; Kuang, B.; Jenkins, K.W. Integration of renewable energy sources in tandem with electrolysis: A technology review for green hydrogen production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 171, 112951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council, W.E.; PwC; E. P. R. I. (EPRI), “Hydrogen on the Horizon: Ready, Almost Set, Go?,” World Energy Council, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/energy-utilities-resources/publications/green-hydrogen-economy.htm.

- Mazumder, G.C.; Hasan, S.; Zishan, M.S.R.; Rahman, M.H. Solar PV- and PEM electrolyzer-based green hydrogen production cost for a selected location in Bangladesh. Academia Green Energy 2023, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chariri, F.; Pawenary, P.; Reza, A.M.; Pariaman, H.; Ramadhon, N.M. , “Techno-Economic Evaluation of Green Hydrogen Production from Off-Grid Solar PV Systems in Remote Areas of Indonesia,” in Proc. 10th Int. Conf. Sci. Technol. (ICST Indonesia, 2024.

- Hassan, Q.; Tabar, V.S.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. A review of green hydrogen production based on solar energy; techniques and methods. Energy Harvesting and Systems 2024, 11, 20220134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahy, B.; Narayan, K.; Rao, B.R. Green hydrogen production by water electrolysis: A renewable energy perspective. Mater. Today: Proc 2022, 67, 1310–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidas, L.; Castro, R. Recent Developments on Hydrogen Production Technologies: State-of-the-Art Review with a Focus on Green-Electrolysis. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, J.O.; Popoola, A.P.I.; Ajenifuja, E.; Popoola, O.M. Hydrogen energy, economy and storage: Review and recommendation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 15072–15086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursúa, A.; Gandía, L.M.; Sanchis, P. Hydrogen production from water electrolysis: Current status and future trends. Proc. IEEE 2012, 100, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Tabar, V.S.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. A review of green hydrogen production based on solar energy; techniques and methods. Energy Harvesting and Systems 2024, 11, 20220134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnabuife, S.G.; Quainoo, K.A.; Hamzat, A.K.; Darko, C.K.; Agyemang, C.K. Innovative Strategies for Combining Solar and Wind Energy with Green Hydrogen Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felseghi, R.A.; Carcadea, E.; Raboaca, M.S.; Trufin, C.N.; Filote, C. Hydrogen fuel cell technology for the sustainable future of stationary applications. Energies 2019, 12, 4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabode, O.E.; Ajewole, T.O.; Okakwu, I.K.; Alayande, A.S.; Akinyele, D.O. Hybrid power systems for off-grid locations: A comprehensive review of design technologies, applications and future trends. Scientific African, vol. 13, p. 00884, O. E. Olabode, T. O. Ajewole, I. K. Okakwu, A. S. Alayande, and D. O. Akinyele, “Hybrid power systems for off-grid locations: A comprehensive review of design technologies, applications and future trends,” Scientific African, vol. 13, p. e00884, 2021.

- Zubairu, N.; Jabri, L.A.; Rejeb, A. A review of hydrogen energy in renewable energy supply chain finance. Dis-cover Sustainability 2025, 6, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).