Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

24 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

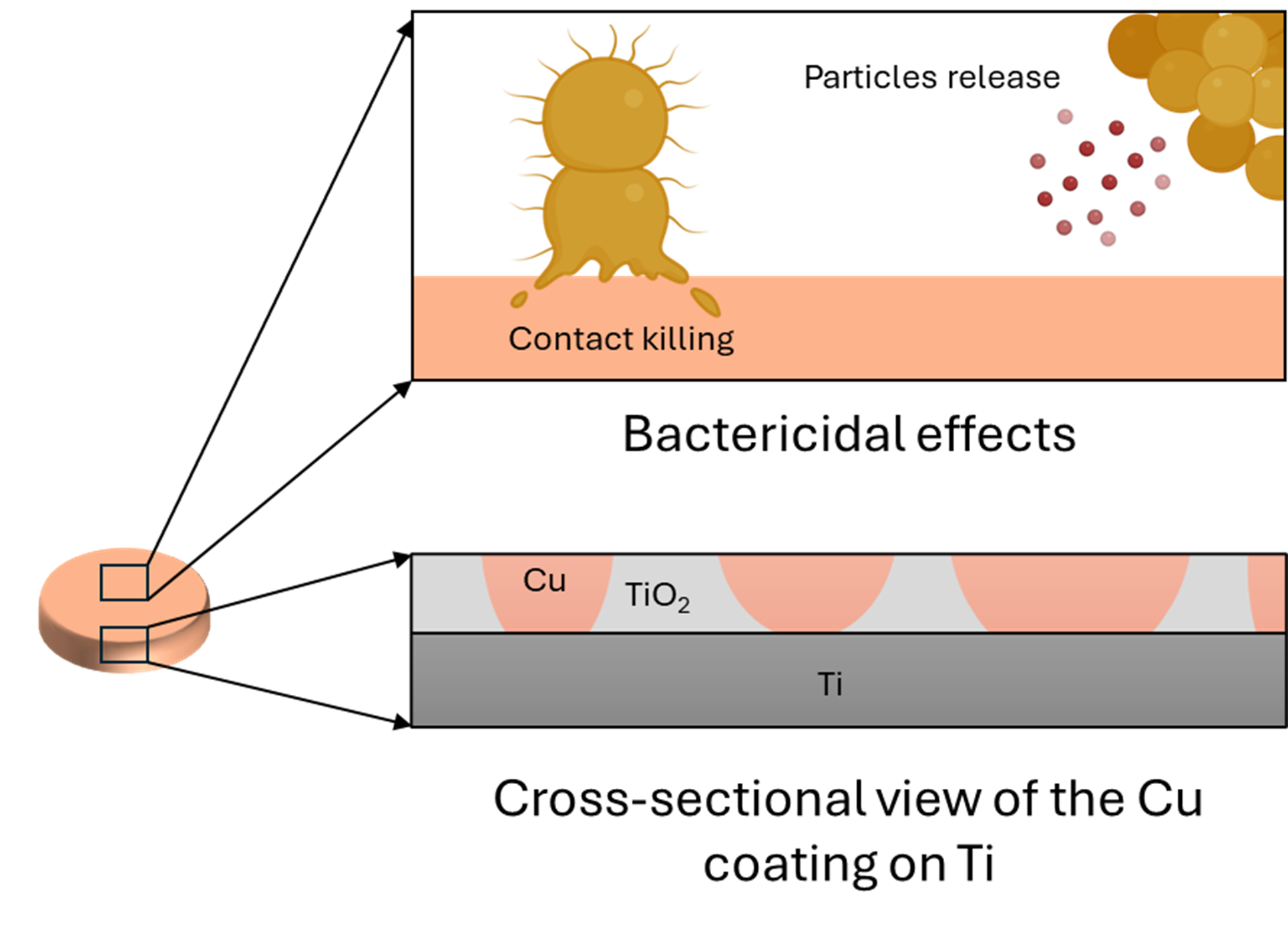

Despite advancements in surgical care, the management of surgical site infections (SSIs) associated with fracture-fixation devices is still a challenge after implant fixation, especially in open fractures. Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a common pathogen of SSIs and contaminates by penetrating the trauma itself (preoperatively) or during insertion of the fixation device (intraoperatively). A unique technology was developed to address this issue, consisting of an antibacterial surface obtained after depositing copper on a porous titanium oxide surface. This study aims to characterize and evaluate the in vitro bactericidal effect of this surface against S. aureus. Furthermore, the topography, elemental composition and other physicochemical properties of the copper coating were determined. In vitro assays have demonstrated a reduction of up to 5 log10 in the bacteria colonization and additional quantitative and qualitative methods further supported these observations. This study illustrates the antibacterial efficacy and killing mechanisms of the surface, therefore proving its potential for minimising infection progression post-implantation in clinical scenarios and bringing important insights for the design of future in vivo evaluations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

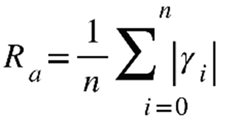

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

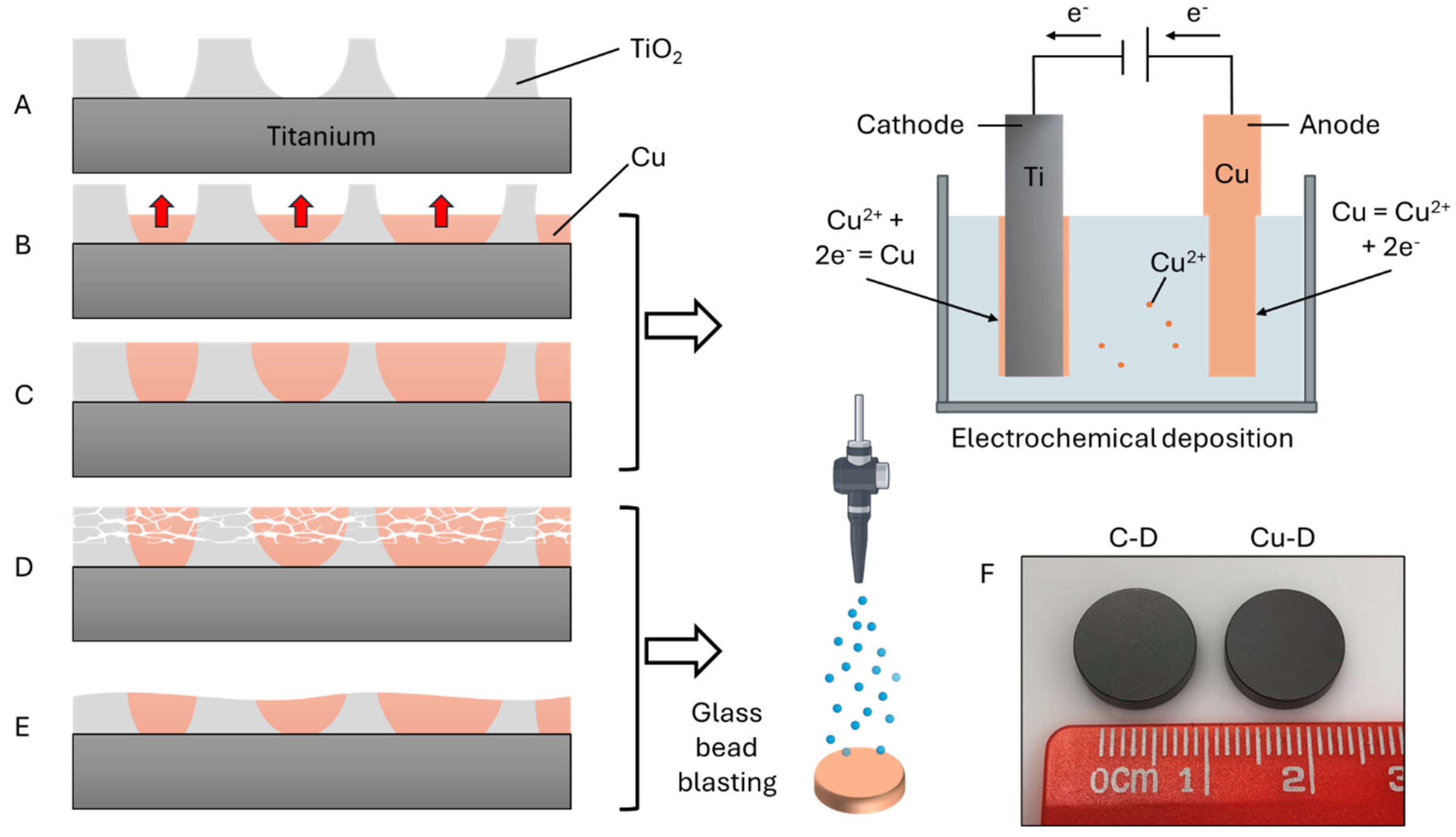

2.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

2.2. Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES)

2.3. Xray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

2.4. Profilometry

2.5. Sessile Dynamic Contact Angle

2.6. Cu Release Profile

2.7. Optical Densitometry

2.8. Antibacterial Activity Assay Measured by CFU Count

2.9. Presto Blue

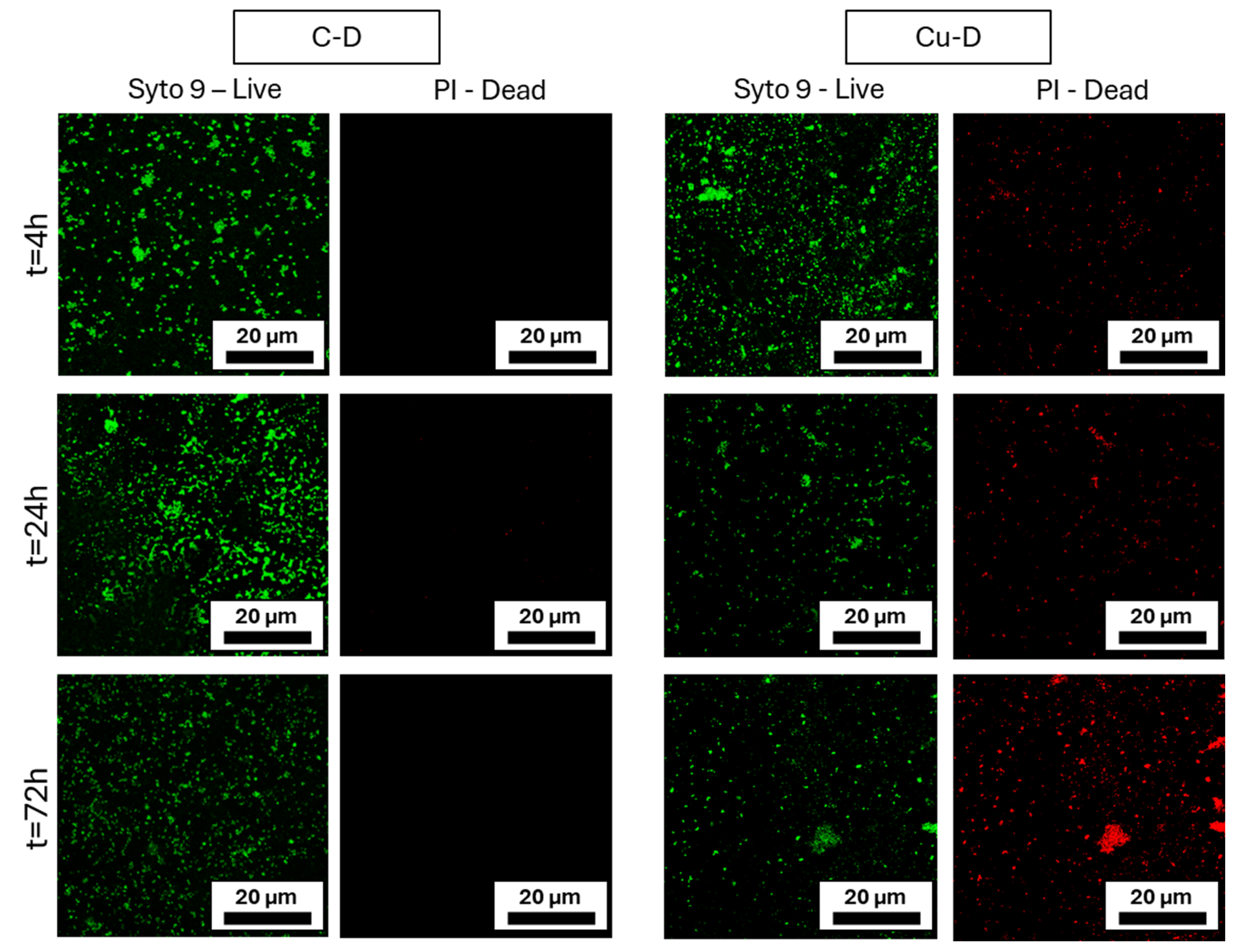

2.10. Live - Dead Staining for Confocal Imaging

2.11. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. SEM Observation and EDS Elemental Analysis

3.2. Cu Surface Elemental Concentration Measured Through Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES)

3.3. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

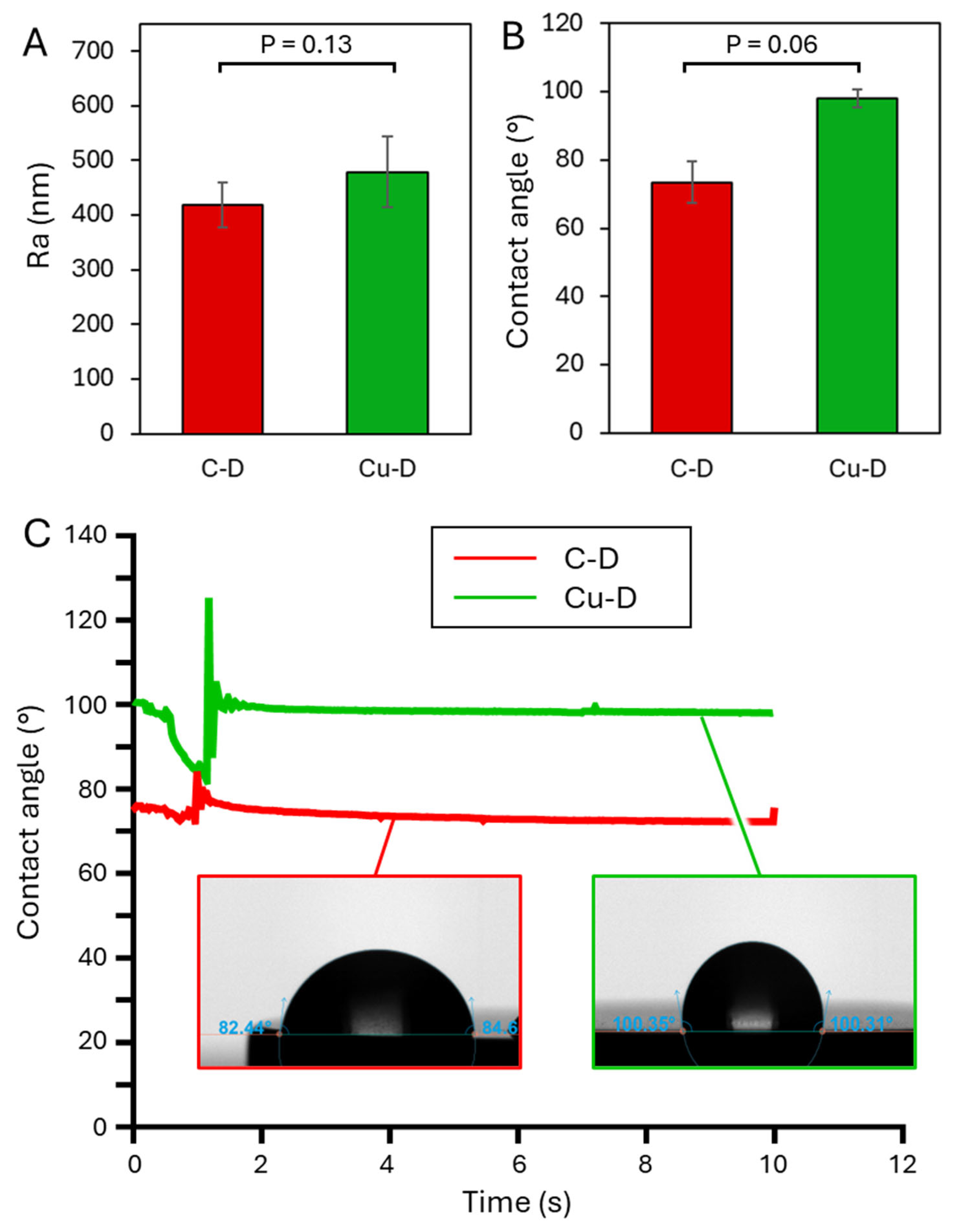

3.4. Surface Profilometer

3.5. Contact Angle – Dynamic mode.

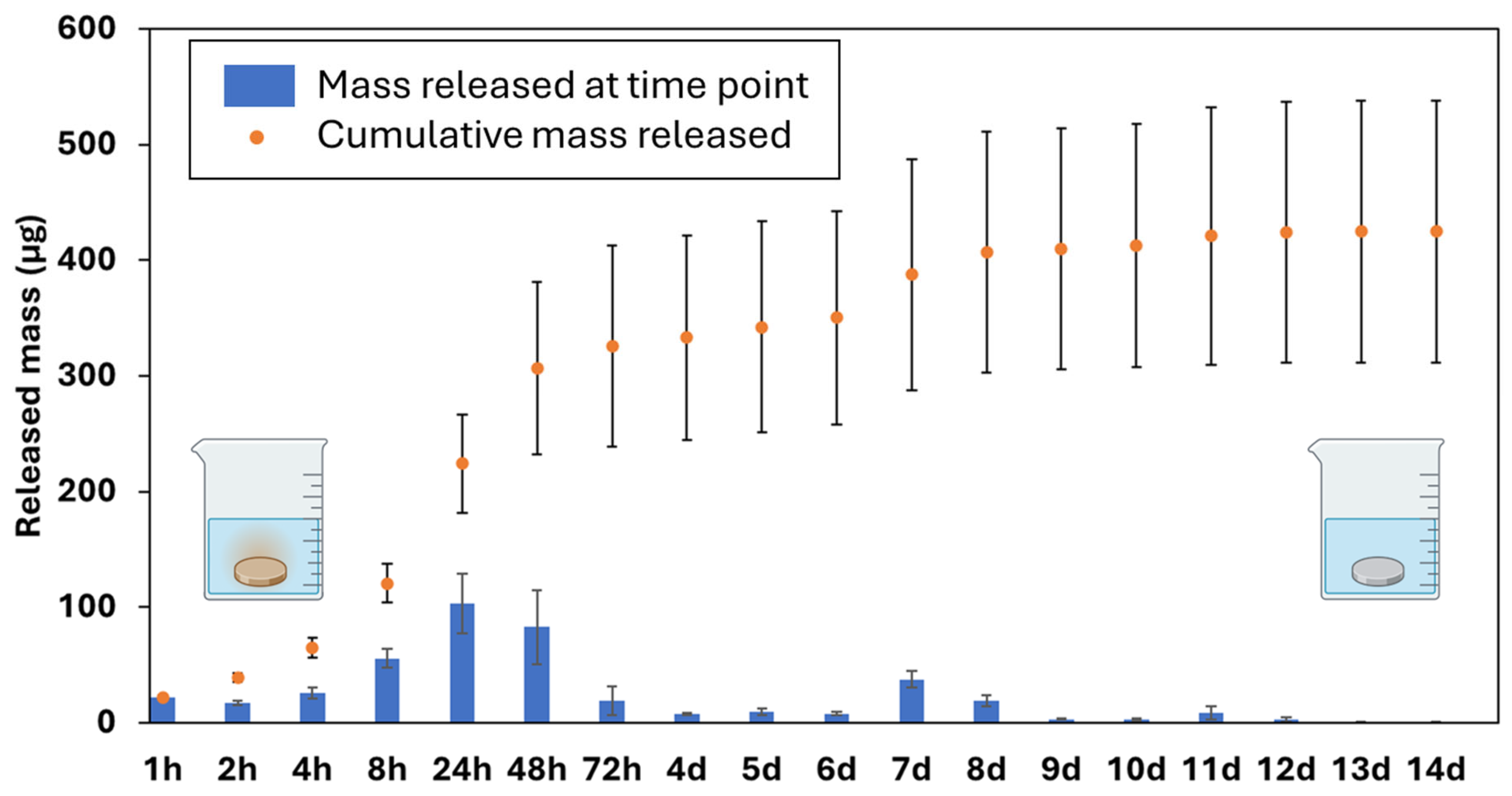

3.6. Cu Release Kinetics via ICP-OES

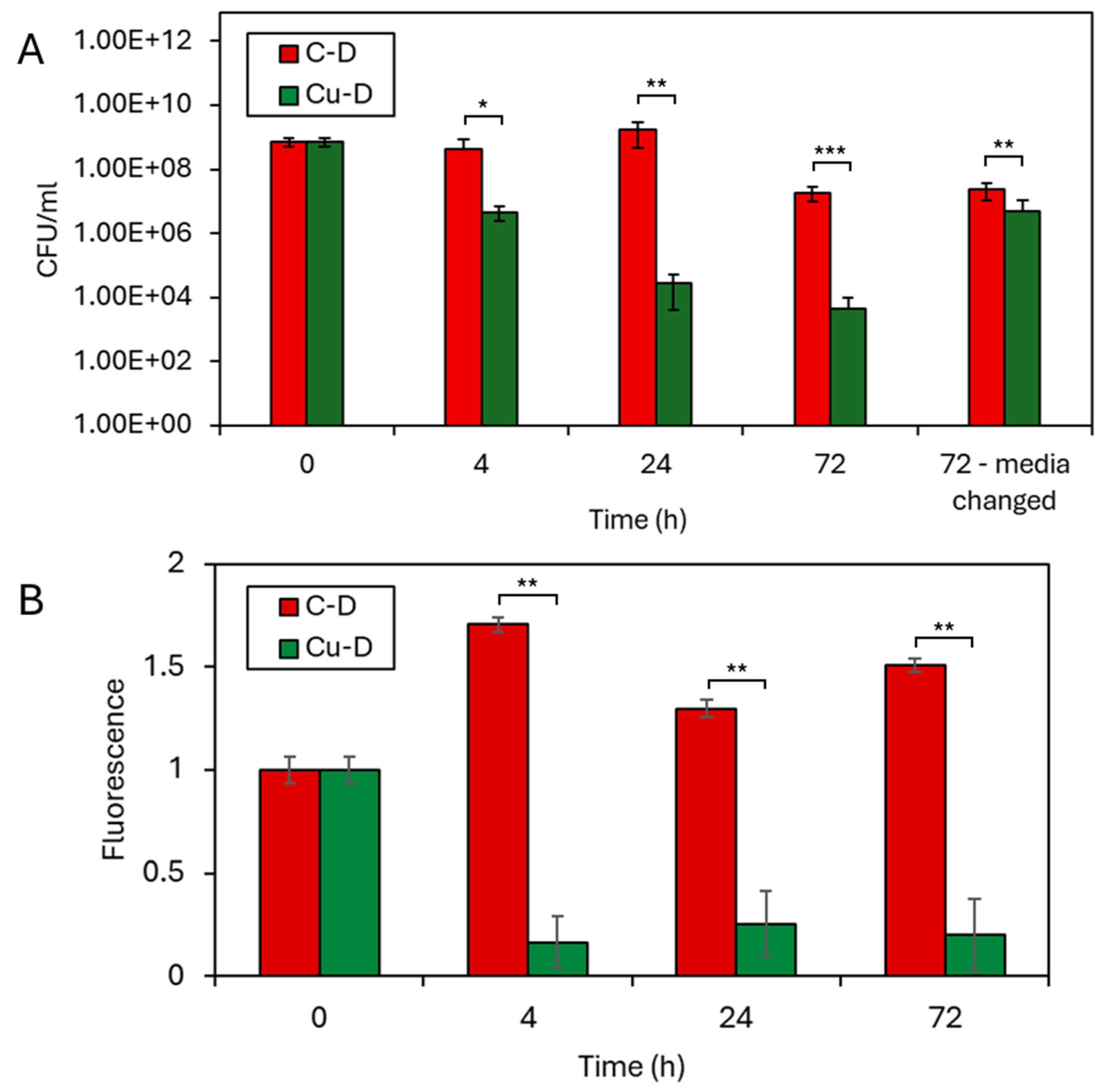

3.7. CFU Counting by Serial Dilution Technique

3.8. Presto Blue Assay

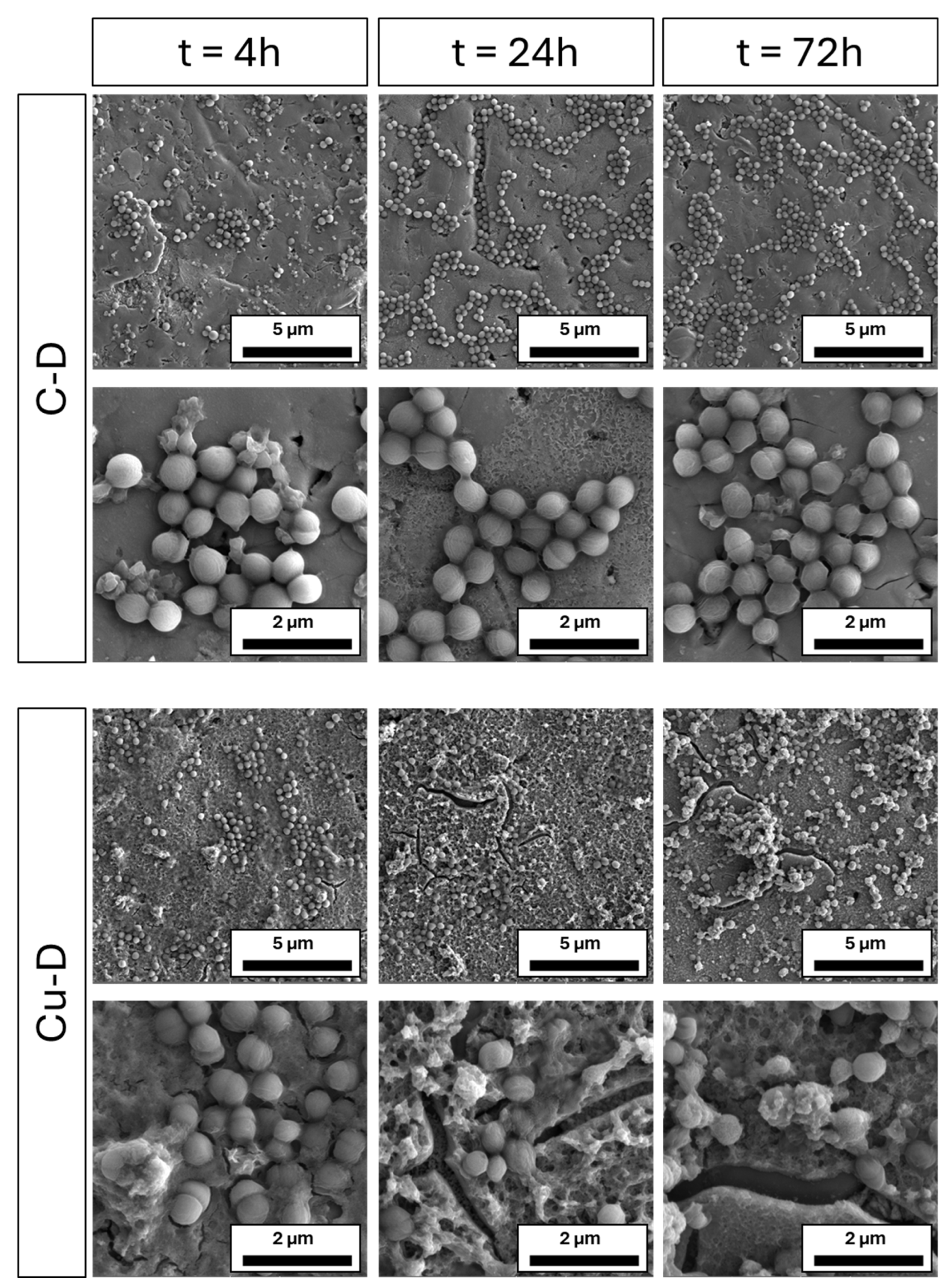

3.9. SEM Imaging

3.10. Live / Dead Imaging

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Conflicts of Interest

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Funding

References

- Meroni, G.; Tsikopoulos, A.; Tsikopoulos, K.; Allemanno, F.; Martino, P.A.; Soares Filipe, J.F. A journey into animal models of human osteomyelitis: a review. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miclau, T. Open fracture management: Critical issues. OTA International 2020, 3, e074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, H.; Smeets, B.; Metsemakers, W.J.; Spitz, A.C.; Nijs, S. Economics of open tibial fractures: the pivotal role of length-of-stay and infection. Health Econ Rev 2017, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, I.A.; Heiner, J.A.; Meremikwu, R.I.; Kellam, J.; Warner, S.J. Where are we in 2022? A summary of 11,000 open tibia fractures over 4 decades. J Orthop Trauma 2023, 37, e326–e334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Feng, Q.; He, X.; Li, M., Zhong; Zhang, K. Relationship between time to surgical debridement and the incidence of infection in patients with open tibial fractures. Orthopaedic Surgery 2020, 12, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, E.M.; Parvizi, J.; Gehrke, T.; Aiyer, A.; Battenberg, A.; Brown, S.A.; Callaghan, J.J.; Citak, M.; Egol, K.; Garrigues, G.E.; et al. 2018 International Consensus Meeting on Musculoskeletal Infection: Research Priorities from the General Assembly Questions. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 2019, 37, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachoura, A.; Guitton, T.G.; Smith, R.M.; Vrahas, M.S.; Zurakowski, D.; Ring, D. Infirmity and injury complexity are risk factors for surgical-site infection after operative fracture care. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011, 469, 2621–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trampuz, A.; Zimmerli, W. Diagnosis and treatment of infections associated with fracture-fixation devices. Injury 2006, 37 (Suppl 2), S59–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, K.V.; Lewis, S.S.; Durkin, M.J.; Baker, A.W.; Moehring, R.W.; Chen, L.F.; Sexton, D.J.; Anderson, D.J. Surveying the surveillance: surgical site infections excluded by the January 2013 updated surveillance definitions. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014, 35, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakore, R.V.; Greenberg, S.E.; Shi, H.; Foxx, A.M.; Francois, E.L.; Prablek, M.A.; Nwosu, S.K.; Archer, K.R.; Ehrenfeld, J.M.; Obremskey, W.T.; et al. Surgical site infection in orthopedic trauma: A case-control study evaluating risk factors and cost. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2015, 6, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, S.M.; Lau, E.; Watson, H.; Schmier, J.K.; Parvizi, J. Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2012, 27, 61–65.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsemakers, W.J.; Handojo, K.; Reynders, P.; Sermon, A.; Vanderschot, P.; Nijs, S. Individual risk factors for deep infection and compromised fracture healing after intramedullary nailing of tibial shaft fractures: a single centre experience of 480 patients. Injury 2015, 46, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvain, T.; Chitnis, A.; Paparouni, K.; Tong, C.; Holy, C.E.; Giannoudis, P.V. The economic burden of infections following intramedullary nailing for a tibial shaft fracture in England. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jernigan, J.A. Is the burden of Staphylococcus aureus among patients with surgical-site infections growing? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2004, 25, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.J.; Sexton, D.J.; Kanafani, Z.A.; Auten, G.; Kaye, K.S. Severe surgical site infection in community hospitals: epidemiology, key procedures, and the changing prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007, 28, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConoughey, S.J.; Howlin, R.; Granger, J.F.; Manring, M.M.; Calhoun, J.H.; Shirtliff, M.; Kathju, S.; Stoodley, P. Biofilms in periprosthetic orthopedic infections. Future Microbiol 2014, 9, 987–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciola, C.R.; Campoccia, D.; Ehrlich, G.D.; Montanaro, L. Biofilm-based implant infections in orthopaedics. Adv Exp Med Biol 2015, 830, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerli, W.; Sendi, P. Orthopaedic biofilm infections. Apmis 2017, 125, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llor, C.; Bjerrum, L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2014, 5, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raschke, M.J.; Rosslenbroich, S.B.; Fuchs, T.F. Antibiotic coated nails. In Intramedullary nailing: a comprehensive guide; Rommens, P.M., Hessmann, M.H., Eds.; Springer London: London, 2015; pp. 555–563. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, S.B.; Yao, Z.; Keeney, M.; Yang, F. The future of biologic coatings for orthopaedic implants. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 3174–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohara, S.; Suthakorn, J. Surface coating of orthopedic implant to enhance the osseointegration and reduction of bacterial colonization: a review. Biomaterials Research 2022, 26, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, W.; Foster, A.L.; Guillaume, O.; Eglin, D.; Schmid, T.; D'Este, M.; Zeiter, S.; Richards, R.G.; Moriarty, T.F. An Antibiotic-Loaded Hydrogel Demonstrates Efficacy as Prophylaxis and Treatment in a Large Animal Model of Orthopaedic Device-Related Infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 826392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, A.L.; Boot, W.; Stenger, V.; D'Este, M.; Jaiprakash, A.; Eglin, D.; Zeiter, S.; Richards, R.G.; Moriarty, T.F. Single-stage revision of MRSA orthopedic device-related infection in sheep with an antibiotic-loaded hydrogel. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society 2021, 39, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.; Barr, S.; Engiles, J.; Hickok, N.J.; Shapiro, I.M.; Richardson, D.W.; Parvizi, J.; Schaer, T.P. Vancomycin-modified implant surface inhibits biofilm formation and supports bone-healing in an infected osteotomy model in sheep: a proof-of-concept study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012, 94, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimeno, M.; Pinczowski, P.; Mendoza, G.; Asín, J.; Vázquez, F.J.; Vispe, E.; García-Álvarez, F.; Pérez, M.; Santamaría, J.; Arruebo, M.; et al. Antibiotic-eluting orthopedic device to prevent early implant associated infections: Efficacy, biocompatibility and biodistribution studies in an ovine model. Journal of biomedical materials research. Part B, Applied biomaterials 2018, 106, 1976–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge-Mora, A.; Amhaz-Escanlar, S.; Fernandez-Pose, S.; García-Iglesias, A.; Mandia-Mancebo, F.; Franco-Trepat, E.; Guillán-Fresco, M.; Pino-Minguez, J. Commercially available antibiotic-laden PMMA-covered locking nails for the treatment of fracture-related infections - A retrospective case analysis of 10 cases. J Bone Jt Infect 2019, 4, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, D.; Kabata, T.; Ohtani, K.; Kajino, Y.; Shirai, T.; Tsuchiya, H. Inhibition of biofilm formation on iodine-supported titanium implants. Int Orthop 2017, 41, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Y.; Choi, H.; Kushida, Y.; Bhayana, B.; Wang, Y.; Hamblin, M.R. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial effects of photocatalysis using titanium dioxide nanoparticles are strongly potentiated by addition of potassium iodide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 5445–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, E.H.; van Doorne, H.; de Vries, S. The lactoperoxidase system: the influence of iodide and the chemical and antimicrobial stability over the period of about 18 months. J Appl Microbiol 2000, 89, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. Nanosurface modification of Ti64 implant by anodic fluorine-doped alumina/titania for orthopedic application. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2022, 281, 125867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Le, P.T.M.; Shintani, S.A.; Takadama, H.; Ito, M.; Ferraris, S.; Spriano, S. Iodine-loaded calcium titanate for bone repair with sustainable antibacterial activity prepared by solution and heat treatment. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, D.; Kabata, T.; Kajino, Y.; Shirai, T.; Tsuchiya, H. Iodine-supported titanium implants have good antimicrobial attachment effects. J Orthop Sci 2019, 24, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daeschlein, G. Antimicrobial and antiseptic strategies in wound management. Int Wound J 2013, 10 Suppl 1, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lollobrigida, M.; Filardo, S.; Sessa, R.; Di Pietro, M.; Bozzuto, G.; Molinari, A.; Lamazza, L.; Vozza, I.; De Biase, A. Antibacterial activity and impact of different antiseptics on biofilm-contaminated implant surfaces. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, A.; Sen, P.; Su, B.; Briscoe, W.H. Natural and bioinspired nanostructured bactericidal surfaces. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2017, 248, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oopath, S.V.; Baji, A.; Abtahi, M.; Luu, T.Q.; Vasilev, K.; Truong, V.K. Nature-inspired biomimetic surfaces for controlling bacterial attachment and biofilm development. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2023, 10, 2201425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddoes, C.M.; Case, C.P.; Briscoe, W.H. Understanding nanoparticle cellular entry: A physicochemical perspective. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2015, 218, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, K.; Liang, H.; Ming, W. Recent advances in superhydrophobic and antibacterial coatings for biomedical materials. Coatings 2022, 12, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linklater, D.P.; Ivanova, E.P. Nanostructured antibacterial surfaces – What can be achieved? Nano Today 2022, 43, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemire, J.A.; Harrison, J.J.; Turner, R.J. Antimicrobial activity of metals: mechanisms, molecular targets and applications. Nat Rev Microbiol 2013, 11, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, R.J. Metal-based antimicrobial strategies. Microb Biotechnol 2017, 10, 1062–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkett, M.; Dover, L.; Cherian Lukose, C.; Wasy Zia, A.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Recent advances in metal-based antimicrobial coatings for high-touch surfaces. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Zhao, X.; Hu, J.; Wang, R.; Fu, S.; Qin, G. Antibacterial metals and alloys for potential biomedical implants. Bioactive Materials 2021, 6, 2569–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fordham, W.R.; Redmond, S.; Westerland, A.; Cortes, E.G.; Walker, C.; Gallagher, C.; Medina, C.J.; Waecther, F.; Lunk, C.; Ostrum, R.F.; et al. Silver as a bactericidal coating for biomedical implants. Surface and Coatings Technology 2014, 253, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, C.E.; Quaranta, D.; Grass, G. Antimicrobial metallic copper surfaces kill Staphylococcus haemolyticus via membrane damage. Microbiologyopen 2012, 1, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudkov, S.V.; Burmistrov, D.E.; Serov, D.A.; Rebezov, M.B.; Semenova, A.A.; Lisitsyn, A.B. A mini review of antibacterial properties of ZnO nanoparticles. Frontiers in Physics 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S.A.; Obeid, S.; Ahlenstiel, C.; Ahlenstiel, G. The role of zinc in antiviral immunity. Adv Nutr 2019, 10, 696–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijnendonckx, K.; Leys, N.; Mahillon, J.; Silver, S.; Van Houdt, R. Antimicrobial silver: uses, toxicity and potential for resistance. Biometals 2013, 26, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, A.; Liu, S.; Fu, Q.; Xu, Y.; Dai, J.; Li, P.; Xu, S. Cytotoxicity of biodegradable zinc and its alloys: a systematic review. Journal of Functional Biomaterials 2023, 14, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.; Hartemann, P.; Engels-Deutsch, M. Antimicrobial applications of copper. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2016, 219, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.; Duval, R.E.; Hartemann, P.; Engels-Deutsch, M. Contact killing and antimicrobial properties of copper. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2018, 124, 1032–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grass, G.; Rensing, C.; Solioz, M. Metallic copper as an antimicrobial surface. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2011, 77, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.P. Effect of copper-impregnated composite bed linens and patient gowns on healthcare-associated infection rates in six hospitals. J Hosp Infect 2018, 100, e130–e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noyce, J.O.; Michels, H.; Keevil, C.W. Potential use of copper surfaces to reduce survival of epidemic meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the healthcare environment. J Hosp Infect 2006, 63, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, E.A.; Velapatino, B.; Akbari Khorami, H.; Donnelly-Pierce, T.; Wong, T.; Dixon, R.; Asselin, E. In vitro evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy and durability of three copper surfaces used in healthcare. Biointerphases 2020, 15, 011005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, M.K.; Williams, T.C.; Nakhaie, D.; Woznow, T.; Velapatino, B.; Lorenzo-Leal, A.C.; Bach, H.; Bryce, E.A.; Asselin, E. In vitro assessment of antibacterial and antiviral activity of three copper products after 200 rounds of simulated use. BioMetals 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, D.A.; Arellano, C.; Pardo, M.; Vera, R.; Gálvez, R.; Cifuentes, M.; Berasain, M.A.; Gómez, M.; Ramírez, C.; Vidal, R.M. Antimicrobial properties of a novel copper-based composite coating with potential for use in healthcare facilities. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control 2019, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo-Osorno, P.M.; Turner, A.B.; Barros, S.M.; Büscher, R.; Guttau, S.; Asa'ad, F.; Trobos, M.; Palmquist, A. Anodized Ti6Al4V-ELI, electroplated with copper is bactericidal against Staphylococcus aureus and enhances macrophage phagocytosis. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2025, 36, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidenau, F.; Mittelmeier, W.; Detsch, R.; Haenle, M.; Stenzel, F.; Ziegler, G.; Gollwitzer, H. A novel antibacterial titania coating: Metal ion toxicity and in vitro surface colonization. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 2005, 16, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haenle, M.; Fritsche, A.; Zietz, C.; Bader, R.; Heidenau, F.; Mittelmeier, W.; Gollwitzer, H. An extended spectrum bactericidal titanium dioxide (TiO2) coating for metallic implants: in vitro effectiveness against MRSA and mechanical properties. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2011, 22, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargioni, C.; Borzenkov, M.; D’Alfonso, L.; Sperandeo, P.; Polissi, A.; Cucca, L.; Dacarro, G.; Grisoli, P.; Pallavicini, P.; D’Agostino, A.; et al. Self-assembled monolayers of copper sulfide nanoparticles on glass as antibacterial coatings. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiedler, J.; Kolitsch, A.; Kleffner, B.; Henke, D.; Stenger, S.; Brenner, R.E. Copper and silver ion implantation of aluminium oxide-blasted titanium surfaces: proliferative response of osteoblasts and antibacterial effects. Int J Artif Organs 2011, 34, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherenda, N.N.; Basalai, A.V.; Shymanski, V.I.; Uglov, V.V.; Astashynski, V.M.; Kuzmitski, A.M.; Laskovnev, A.P.; Remnev, G.E. Modification of Ti-6Al-4V alloy element and phase composition by compression plasma flows impact. Surface and Coatings Technology 2018, 355, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegan, G.; Cimpoesu, N.; Agop, M.; Stirbu, I.; Chicet, D.; Istrate, B.; Alexandru, A.; Prisacariu, B. Improving the HA deposition process on ti-based advanced alloy through sandblasting. OPTOELECTRONICS AND ADVANCED MATERIALS-RAPID COMMUNICATIONS 2016, 10, 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Yuda, A.; Supriadi, S.; Saragih, A. Surface modification of Ti-alloy based bone implant by sandblasting, 2019.

- Polishetty, A.; Manoharan, V.; Littlefair, G.; Sonavane, C. Machinability assessment of Ti-6Al-4V for aerospace applications. ASME Early Career Technical Journal 2013, 12, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, L.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, R.; Li, G.; Zhang, R.; Xiang, J.; et al. Copper-doped 3D porous coating developed on Ti-6Al-4V alloys and its in vitro long-term antibacterial ability. Applied Surface Science 2020, 509, 144717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Thompson, G.E.; Skeldon, P.; Shimizu, K.; Habazaki, H.; Wood, G.C. The valence state of copper in anodic films formed on Al-1at.% Cu alloy. Corrosion 2005, 47, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, S.S.d.; Adabo, G.L.; Henriques, G.E.P.; Nóbilo, M.A.d.A. Vickers hardness of cast commercially pure titanium and Ti-6Al-4V alloy submitted to heat treatments. Brazilian Dental Journal 2006, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulyadi; Ramlan, R.; Aini, S.; Djuhana. Effect of various sintering temperature of ceramic TiO2 on physical properties and crystall structure. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2019, 1282, 012049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianchao, Y.; Wang, G.; Rong, Y. Experimental study on the surface integrity and chip formation in the micro cutting process. Procedia Manufacturing 2015, 1, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Ding, S.J.; Chen, C.C. Effects of surface conditions of titanium dental implants on bacterial adhesion. Photomed Laser Surg 2016, 34, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruparelia, J.P.; Chatterjee, A.K.; Duttagupta, S.P.; Mukherji, S. Strain specificity in antimicrobial activity of silver and copper nanoparticles. Acta Biomaterialia 2008, 4, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | Time points & media change | |

|---|---|---|

| Negative control | C-D sample No bacteria |

4h, 24h, 72h No media change |

| 72h Media change at 24h and 48h | ||

| Positive control | C-D sample S. aureus, 1-5 × 108 CFU/ml |

4h, 24h, 72h No media change |

| 72h Media change at 24h and 48h | ||

| Experimental | Cu-D sample S. aureus, 1-5 × 108 CFU/ml |

4h, 24h, 72h No media change |

| 72h Media change at 24h and 48h | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).