Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming democratic policymaking, with examples like Estonia’s automated regulation drafting and the European Union’s AI-driven impact analyses. While these advancements enhance efficiency and provide evidence-based insights, they raise critical concerns about democratic legitimacy—specifically, whether citizens can trust laws influenced by algorithmic systems. As Schneier and Sanders (2025) highlight, AI can produce inaccurate results and may ignore fundamental democratic values like fairness and equality, particularly in sensitive legislative situations.

Traditionally, democratic legitimacy has depended on human-centered practices such as transparent deliberation, accountable representation, and broad public participation (Sigfrids et al., 2023). However, recent research suggests that AI’s rigid logic may stifle diverse perspectives and critical reasoning, worsening existing democratic deficits (Frimpong, 2025b).

The incorporation of AI in lawmaking can undermine these essential practices by introducing opacity and unclear accountability (Yahia & Miran, 2022; Buhmann & Fieseler, 2022). Scholars argue that conventional AI ethics, emphasizing transparency and fairness, often mischaracterize AI as a neutral tool, overlooking its ties to power and inequality (Frimpong, 2025a). Buhmann and Fieseler (2022) advocate for deep democratic deliberation, urging stakeholders from various sectors to engage in meaningful discussions about AI’s roles and governance. Without such engagement, there’s a risk that technology, rather than elected officials, will dictate the legislative agenda.

This paper explores not just the role of AI in policymaking, but also how it can be integrated without compromising democratic principles. Using the Triadic Legitimacy Model (TLM), we examine the interplay of transparency, human oversight, and public involvement in maintaining or undermining democratic trust. By considering AI as a co-governing actor instead of a mere tool, the paper calls for a reassessment of democratic structures and norms in the context of algorithmic governance.

Democracy, Legitimacy, and Technology

The integration of AI into legislative processes cannot be understood without revisiting the theories of legitimacy that underpin democratic governance. Legitimacy determines not only whether laws are obeyed but also whether institutions retain public trust during periods of transformation.

Input, Throughput, and Output Legitimacy

Scharpf (1999) and Schmidt (2013) conceptualize legitimacy along three interdependent dimensions:

Input legitimacy emphasizes representation and participation — the extent to which citizens influence policymaking through elections, consultations, and advocacy.

Throughput legitimacy reflects the quality, transparency, and accountability of the decision-making process itself, including procedural fairness and deliberative integrity.

Output legitimacy refers to the effectiveness and performance of policies — whether laws deliver outcomes that align with public needs and societal goals.

AI influences all three dimensions simultaneously. For instance, AI-driven policy simulations can enhance output legitimacy by improving the accuracy and responsiveness of laws. However, if these systems operate opaquely, they risk undermining the legitimacy of their throughput, while limited opportunities for public input threaten the legitimacy of their input.

Technological Legitimacy and Perceived Fairness

Emerging literature on technological legitimacy (Brynjolfsson & Mitchell, 2018; Danaher, 2016) suggests that public trust in AI depends on perceived fairness, explainability, and human control. Systems that are transparent and auditable tend to foster acceptance, while opaque or biased models erode confidence. In the legislative context, legitimacy hinges on whether citizens believe AI supports human decision-makers rather than replacing them.

This perception is dynamic. A transparent AI platform that explains, in plain language, how it informed a tax reform proposal may be seen as augmenting deliberation. Conversely, an inscrutable system shaping criminal justice policies risks being perceived as illegitimate, even if technically accurate.

Historical Parallels: From Expert Bureaucracies to Technocratic Governance

History offers useful parallels. The rise of expert bodies in the 20th century, like economic planning boards and regulatory agencies, improved policy precision but also highlighted a disconnect between expertise and public involvement. This challenge has intensified with the emergence of AI, which complicates the need for democratic legitimacy.

Turtz (2025) discusses how expert systems struggle to align with democratic processes, creating accountability issues despite their technical advancements. While bureaucracies can enhance policy accuracy, they often sacrifice transparency and public trust, emphasizing the need for effective democratic oversight. Jalušič and Heuer (2024) advocate for a governance model that embraces pluralism and deliberation. This aligns with the challenges of AI, as algorithms prioritize optimization over the ethical pluralism necessary for democracy. They argue that governance must adapt to include diverse perspectives for legitimacy in decision-making. The study by Pan et al. (2022) highlights the legitimacy issues faced by algorithmic systems compared to human oversight in content moderation. Automated systems, while efficient, often lack the perceived legitimacy of human decisions, raising questions about reconciling algorithmic decision-making with democratic norms that value accountability and public discourse. Krick (2021) emphasizes citizen involvement in governance to enhance democratic legitimacy. By incorporating local knowledge and participatory practices, policymakers can create a more inclusive environment, which is essential in an AI-driven era. Finally, White and Neblo (2021) argue for integrating deliberative practices into the administrative state, essential for balancing technical expertise with public input. This balance is vital for achieving legitimacy as governance mechanisms evolve to include advanced AI systems.

These studies highlight the urgent need to reevaluate governance frameworks due to AI’s growing involvement in policymaking. As AI systems take on a more active role in drafting and analyzing policies, they become more than just tools; they influence the legislative process. This change raises important questions about authority, accountability, and trust between human lawmakers and AI systems. The following section will explore AI as a co-governing entity, emphasizing its structural impact on legislative decisions. Understanding this perspective is crucial for ensuring that AI integration strengthens rather than undermines democracy.

Conceptualizing AI as a Co-Governing Actor

The integration of AI into legislative processes requires a new perspective: AI is not just a tool but an active participant in the creation and implementation of laws. This shift is crucial for recognizing the opportunities and risks associated with algorithmic governance in democracies.

From Tool to Actor

Traditionally, technology in governance was seen as a neutral tool for implementing human intent (Winner, 1980). However, recent research in science and technology studies (Latour, 2005; Crawford, 2021) highlights that complex systems like AI influence decision-making, shape priorities, and frame policy discussions. In legislative contexts, AI systems can analyze extensive legal and socio-economic data. They highlight specific trends or risks, shape bill language by embedding technical assumptions, and prioritize policy options by providing data-driven recommendations that influence lawmakers’ decisions. Although not human, this technology exercises significant structural power that deserves careful analysis.

The Rise of Human–Machine Co-Governance

AI-assisted lawmaking is a collaborative process between human legislators and computer systems, where authority is shared and distributed adaptively:

Humans maintain ultimate authority by offering normative judgments and ensuring democratic accountability.

AI systems function as collaborative aids, providing predictive modeling, drafting assistance, and impact analysis that considerably surpass human cognitive capabilities.

The role of AI varies depending on the stakes of the legislation. In low-stakes situations, like administrative updates, AI can take a more significant role. However, in high-stakes areas, such as criminal justice or constitutional reform, human oversight becomes more critical. This variation creates new challenges in building trust and negotiating authority (Lee & See, 2004).

Democratic Tensions

Viewing AI as a co-governing actor reveals three key tensions in democratic theory:

Authority vs. Accountability: As AI plays a larger role in drafting legislation, it leads to blurred accountability. Legislators may depend on AI outputs but often lack the technical skills to assess them critically, resulting in gaps in responsibility.

Efficiency vs. Deliberation: AI speeds up legislative processes, but this rapid pace can compromise the thorough debate necessary for democratic legitimacy. Quickly produced laws may miss the in-depth discussions required for broad acceptance and social consensus.

Expertise vs. Inclusion: AI-driven governance favors technical experts, which may exclude non-technical perspectives from legislative discussions. This is similar to past criticisms of technocracy, but the risks are greater due to the complexity and lack of transparency in AI.

Toward a Normative Reframing

Recognizing AI as a co-governing actor does not mean giving it autonomy or legal status. It highlights the necessity of creating institutional guardrails that balance algorithmic efficiency with democratic accountability. By incorporating AI into frameworks that emphasize transparency, oversight, and public participation, legislatures can utilize their computational power while preserving public trust. This perspective leads to the Triadic Legitimacy Model (TLM), which defines how AI involvement in lawmaking can enhance democratic legitimacy.

The Triadic Legitimacy Model (TLM)

The Triadic Legitimacy Model (TLM) outlines how to incorporate AI into legislative processes while maintaining trust in democracy. It focuses on three key pillars that support legitimacy: Transparency and Explainability, Human Oversight and Accountability, and Public Engagement.

Pillar 1: Transparency and Explainability

Legitimacy in democratic systems relies on clear decision-making (Schmidt, 2013). AI complicates this by creating a “black box” effect, even for experts. To maintain trust, AI in legislation must be auditable, its reasoning explained clearly, and its impact on drafts traceable. Without these steps, citizens may view AI-assisted laws as unclear and untrustworthy.

Pillar 2: Human Oversight and Accountability

Democracy mandates that elected officials maintain authority over decisions (Novelli et al., 2023). AI should serve as an advisory tool rather than acting independently. This requires implementing human-in-the-loop protocols, clear accountability, and ethical overrides when human judgment differs from algorithmic suggestions. Oversight is essential to ensure AI enhances, not replaces, democratic decision-making.

Pillar 3: Public Engagement

Legitimacy involves both process and participation (Habermas, 1996). AI should be used to boost citizen involvement, not reduce it. This means creating AI platforms for gathering public feedback, offering clear educational tools for legislative proposals, and ensuring access for marginalized voices. When citizens notice their views in policymaking, their trust in AI-assisted processes increases.

Interaction of the Three Pillars

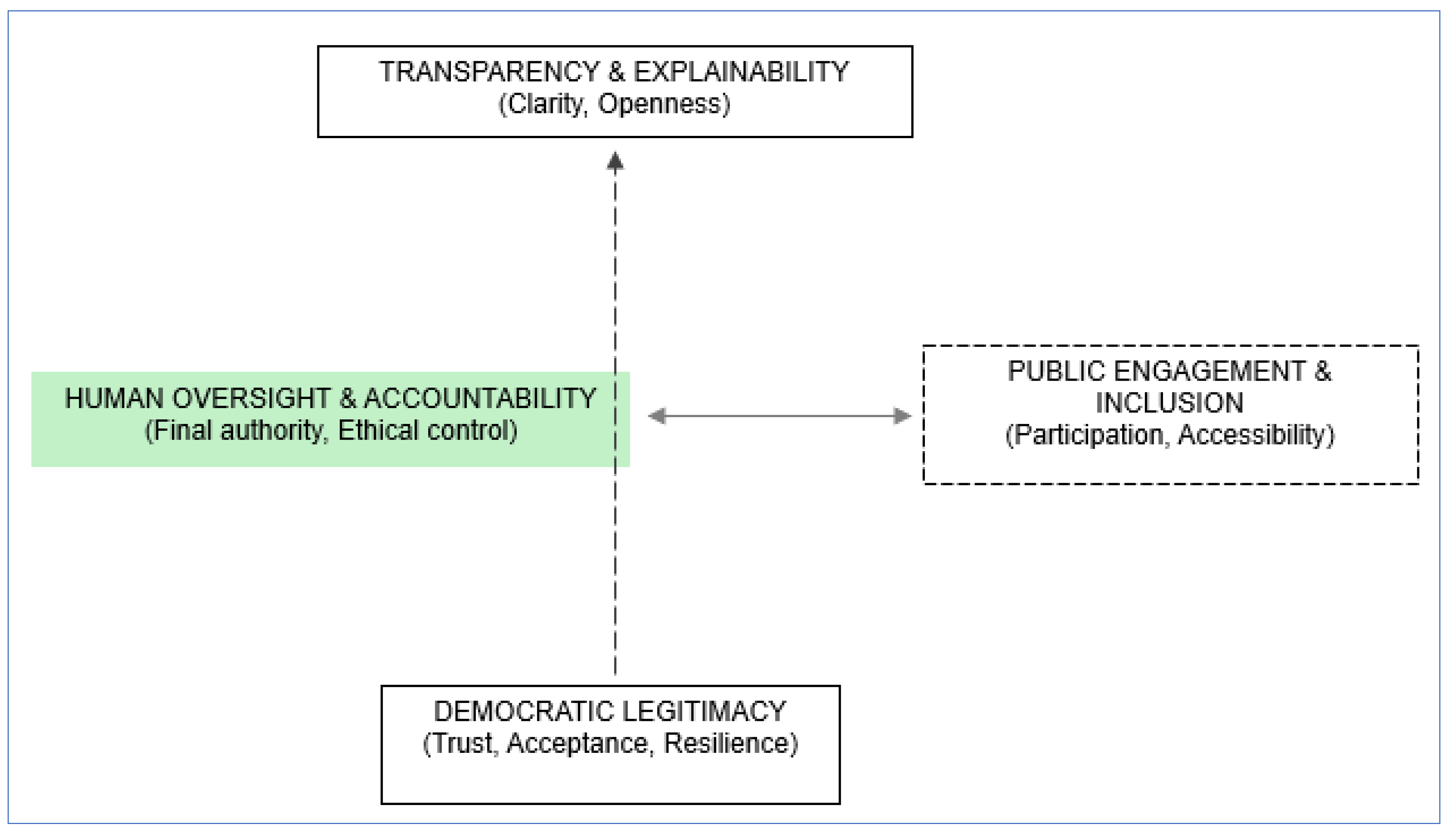

The TLM highlights that legitimacy emerges from the interaction of three pillars: transparency, oversight, and engagement (

Table 1). Transparency needs oversight to avoid technocratic issues; oversight must involve citizen engagement to bridge the gap between policymakers and citizens; and engagement requires transparency to ensure meaningful participation. A balanced integration of these pillars strengthens legitimacy in AI-assisted lawmaking.

This table outlines how the three pillars—transparency and explainability, human oversight and accountability, and public engagement and inclusion—affect perceptions of legitimacy in AI-assisted lawmaking. Varying combinations of these pillars can lead to outcomes ranging from strong public trust to diminished democratic legitimacy.

Figure 1 illustrates how transparency, human oversight, and public engagement interact to enhance or weaken legitimacy in AI-assisted lawmaking.

This figure shows the three key pillars of the TLM that support democratic legitimacy in the use of AI in legislative processes:

1. Transparency and Explainability (top): AI systems in lawmaking must be clear and understandable, providing reasoning for their recommendations. This builds public trust and avoids the “black box” issue.

2. Human Oversight and Accountability (bottom left): Elected officials must retain ultimate decision-making power. Oversight mechanisms like ethical review boards and audit protocols are essential to prevent over-reliance on automation and ensure accountability.

3. Public Engagement and Inclusion (bottom right): It’s important to involve citizens and stakeholders in the policymaking process through participatory platforms and educational initiatives. This ensures AI supports, rather than undermines, democratic participation.

Maintaining a balance among these pillars is crucial. If any area is weak—such as a lack of transparency, oversight, or engagement—democratic legitimacy and public trust can be compromised.

Balancing transparency, accountability, and inclusiveness leads to high legitimacy and citizen trust in laws. Weakness in any of these pillars undermines the system:

Low transparency → opacity and mistrust.

Weak oversight → technocratic drift and accountability gaps.

Poor engagement → public alienation and legitimacy erosion.

Theoretical Contribution

The Triadic Legitimacy Model (TLM) contributes significantly to the research on democratic theory, algorithmic governance, and technology studies in three key ways.

Extending Procedural Justice Theory to Algorithmic Governance

The TLM builds on procedural justice theories (Tyler, 2006; Scharpf, 1999) by incorporating AI into lawmaking. While traditional frameworks focus on fairness, transparency, and participation in human-centered systems, the TLM views AI as an active participant in legislative processes. It shows that in the algorithmic era, legitimacy depends not only on institutional design but also on how citizens understand, govern, and trust algorithmic processes.

Operationalizing Trust and Legitimacy Conditions in Legislative AI

Previous research has explored trust in automation (Lee & See, 2004), but few frameworks address this in democratic contexts. The Trust Legitimacy Model (TLM) offers a framework to analyze trust through three key pillars:

- Transparency and Explainability: Clarity of processes and outcomes.

- Human Oversight and Accountability: Ensuring human agency is maintained.

- Public Engagement and Inclusion: Involving the public in discussions.

This model can assess legitimacy in legislative systems with different levels of AI integration, from advisory roles to full co-drafting processes.

Establishing a Normative Baseline for Future Research

The TLM provides a framework for assessing the democratic impact of AI in lawmaking. It sets benchmarks for evaluating public trust, institutional accountability, and procedural fairness. It also encourages comparative research in various democratic contexts, from advanced digital democracies like Estonia to complex systems like the European Union, examining how different factors influence the interplay between AI and legitimacy.

The TLM redefines AI as an active participant in governance, capable of both strengthening and challenging democratic processes. By connecting theory with practical implications, it fosters a deeper understanding of legitimacy in democracies enhanced by algorithms.

Practical Application

The Triadic Legitimacy Model (TLM) offers a clear framework for designing AI-assisted legislative processes. By focusing on its three main pillars — Transparency and Explainability, Human Oversight and Accountability, and Public Engagement — stakeholders can build systems that boost efficiency while maintaining democratic integrity.

For Policymakers and Legislatures

-

Mandate Algorithmic Transparency

The European Union is implementing transparency obligations through the AI Act, requiring public documentation of datasets, models, and decision-making processes. Similar global mandates can help citizens and lawmakers comprehend how AI influences policy.

- ○

Challenge: Technical complexity often hinders the consistent delivery of “plain-language” outputs, necessitating investment in explainable AI research.

-

Embed Human-in-the-Loop Protocols

In Estonia, early pilots of AI-assisted regulatory drafting show that human oversight is essential in all stages of lawmaking. Legislators maintain ultimate authority, keeping AI in an advisory role only.

- ○

Challenge: Over-reliance on AI-generated insights can still lead to subtle automation bias, where humans defer to algorithmic authority without critical scrutiny.

-

Create Oversight and Ethics Boards

Create independent, multidisciplinary boards to assess AI systems for fairness, accountability, and adherence to democratic principles. The UK’s Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (CDEI) offers a governance model that could be adapted for legislative use.

- ○

Challenge: Oversight bodies must remain politically independent to avoid regulatory capture or partisan influence.

For Technology Developers

-

Build for Auditability

AI developers must create systems with traceability logs and explainable outputs for external audits. Open-source platforms, such as OpenAI’s policy transparency tools, serve as valuable models.

- ○

Challenge: Commercial AI vendors may oppose complete transparency due to concerns over intellectual property, leading to a conflict between transparency and proprietary interests.

-

Integrate Ethical Guardrails

Incorporating bias detection and fairness metrics during model training, as demonstrated by Google’s Model Cards, ensures that outputs meet democratic and ethical standards.

- ○

Challenge: The effectiveness of ethical guardrails depends on the quality of the underlying data; biased datasets can perpetuate systemic inequities.

-

Co-Design with Users

Collaborative design workshops with lawmakers, legal experts, and civil society help create systems that meet real governance needs. In Canada, co-creation in digital policy tools has led to greater adoption and trust.

- ○

Challenge: Co-design requires significant resources and ongoing involvement from stakeholders to ensure meaningful participation rather than just superficial engagement.

For Civil Society and the Public

-

Demand Participatory Platforms

Taiwan’s vTaiwan platform shows how AI can gather public opinion and influence legislative discussions.

- ○

Challenge: Participation tends to favor digitally literate groups, leading to concerns about representational bias.

-

Promote Digital Literacy

Civil society organizations should launch public education campaigns to clarify AI’s role in policymaking. The success of Finland’s Elements of AI program highlights the importance of improving public understanding of AI concepts.

- ○

Challenge: Scaling these programs needs substantial funding and government backing.

-

Act as Watchdogs

Independent NGOs like the Algorithmic Justice League demonstrate how civil society can track AI biases and push for responsible use of AI.

- ○

Challenge: Watchdog groups frequently lack the resources and expertise needed to effectively influence policy debates.

Implementation Priorities

Table 2.

Implementation Priorities for Operationalizing the Triadic Legitimacy Model (TLM).

Table 2.

Implementation Priorities for Operationalizing the Triadic Legitimacy Model (TLM).

| Priority |

Action |

Example |

Challenge |

| Short-term |

Launch pilot programs with transparent, low-stakes legislative applications. |

Estonia’s early experiments with automated regulatory drafting. |

Managing public expectations while scaling. |

| Medium-term |

Establish oversight boards and enforce open-source or auditable standards. |

EU AI Act mandates and independent audits. |

Risk of political interference or weak enforcement. |

| Long-term |

Scale participatory platforms and integrate continuous feedback loops. |

Taiwan’s vTaiwan model of digital deliberation. |

Ensuring inclusivity and avoiding digital exclusion. |

This table details actions—short-term, medium-term, and long-term—for integrating the TLM framework into legislative processes. It includes practical examples and highlights the challenges of maintaining efficiency, oversight, and inclusion.

Adaptive Governance

Legitimacy is dynamic. Policymakers and developers should implement feedback mechanisms like surveys, audits, and public consultations to monitor trust perceptions and adjust practices as needed. This approach helps ensure AI is a supportive partner in legislative processes rather than an unaccountable authority.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Integrating artificial intelligence (AI) into legislative processes can greatly improve democratic governance. AI enhances lawmaking through quick analysis, predictive modeling, and efficient drafting, making it more responsive and evidence-based. However, this integration also brings risks like algorithmic opacity, accountability issues, and a possible shift towards technocracy, which could undermine democratic legitimacy if not carefully managed.

The Triadic Legitimacy Model (TLM) presents AI as a key co-governing actor rather than a neutral tool, emphasizing the need for its management through a three-pillar framework:

Transparency and Explainability to ensure clarity and procedural trust.

Human Oversight and Accountability to safeguard normative and ethical authority.

Public Engagement and Inclusion to preserve the participatory foundation of democracy.

This model establishes a baseline for assessing algorithmic governance in legislative settings and acts as a framework for policy and institutional design. By incorporating these key pillars, democracies can leverage AI’s strengths while preserving core values.

Future research should empirically test this model in various democratic contexts, focusing on how cultural, institutional, and technological factors influence public perceptions of legitimacy. Longitudinal studies are essential to understand how trust changes as AI systems transition from advisory roles to integral parts of legislative processes. Comparative studies, such as between tech-savvy democracies like Estonia and complex systems like the European Union, would enhance both theoretical understanding and practical applications. Ultimately, the key question is how democracies can create the necessary institutional safeguards to ensure AI participation in lawmaking enhances legitimacy rather than undermines it. By focusing on transparency, accountability, and inclusion, democratic systems can adapt to technological advancements while retaining public trust.

References

- Brynjolfsson, E. , Mitchell, T., & Rock, D. (2018). What Can Machines Learn, and What Does It Mean for Occupations and the Economy? AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108(108), 43–47. [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, A. & Fieseler, C. (2022). Deep learning meets deep democracy: deliberative governance and responsible innovation in artificial intelligence. Business Ethics Quarterly, 33(1), 146-179. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, Politics and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300264630/atlas-of-ai/. [CrossRef]

- Danaher, J. (2016). Why Internal Moral Enhancement Might Be Politically Better than External Moral Enhancement. Neuroethics 12 (1):39–54.

- Frimpong, V. (2025a). Rules for Radical AI: A Counter-Framework for Algorithmic Contestation. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, V. (2025b, February 27). Conceptualizing AI as an Intellectual Bully: A Critical Examination. [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. (1996). Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy (Trans. William Rehg). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Jalušič, V. and Heuer, W. (2024). Thinking contemporary forms of government after the break of tradition. Contributions to Political Science, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Krick, E. (2021). Citizen experts in participatory governance: democratic and epistemic assets of service user involvement, local knowledge and citizen science. Current Sociology, 70(7), 994-1012. [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the Social: an Introduction to Actor-network-theory. Oxford University Press.

- Lee, J. D. , & See, K. A. (2004). Trust in automation: Designing for appropriate reliance. Human Factors, 46(1), 50–80. [CrossRef]

- Novelli, C. , Taddeo, M., & Floridi, L. (2023). Accountability in artificial intelligence: what it is and how it works. AI & SOCIETY, 39(1). [CrossRef]

- Pan, C. A. , Yakhmi, S., Iyer, T., Strasnick, E., Zhang, A. X., & Bernstein, M. S. (2022). Comparing the perceived legitimacy of content moderation processes: contractors, algorithms, expert panels, and digital juries. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 6(CSCW1), 1–31. [CrossRef]

- Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V. A. (2013). Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: Input, output and ‘throughput’. Political Studies, 61(1), 2–22. [CrossRef]

- Schneier, B., & Sanders, N. E. (2025, May 14). AI-Generated Law Isn’t Necessarily a Terrible Idea. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/05/14/ai-generated-law-uae-legislation/.

- Sigfrids, A. , Leikas, J., Salo-Pöntinen, H., & Koskimies, E. (2023). Human-centricity in ai governance: a systemic approach. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 6. [CrossRef]

- Turtz, M. (2025). The necessity of bureaucracy and the fixation of legitimacy. International Journal of Ethics and Systems. [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T. R. (2006). Why people obey the law. Princeton University Press.

- White, A. & Neblo, M. A. (2021). Capturing the public: beyond technocracy & populism in the u.s. administrative state. Daedalus, 150(3), 172-187. [CrossRef]

- Winner, L. (1980). Do artifacts have politics? Daedalus, Vol. 109, No. 1, Modern Technology: Problem or Opportunity? pp. 121-136.

- Yahia, H. S. & Miran, A. (2022). Evaluating the electronic government implementation in the kurdistan region of iraq from citizens’ perspective. Humanities Journal of University of Zakho, 10(2). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).