Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Through what specific psychological mechanisms do algorithmic systems influence ethical reasoning and responsibility perception?

- How do these mechanisms manifest across different organizational contexts?

- What evidence-based strategies can organizations implement to maintain ethical engagement when using algorithmic decision systems?

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Moral Agency and Algorithmic Mediation

2.2. Moral Disengagement in Sociotechnical Systems

- Displacement of responsibility: Attributing responsibility to authority figures or systems

- Diffusion of responsibility: Distributing responsibility across multiple actors

- Moral justification: Recasting harmful actions as serving moral purposes

- Advantageous comparison: Contrasting actions with worse alternatives

- Distortion of consequences: Minimizing or ignoring harmful effects

- Dehumanization: Stripping targets of human qualities

- Attribution of blame: Viewing victims as deserving harm

2.3. Distributed Agency and Responsibility Gaps

2.4. Organizational and Contextual Influences on Algorithmic Ethics

2.5. Designing for Ethical Engagement

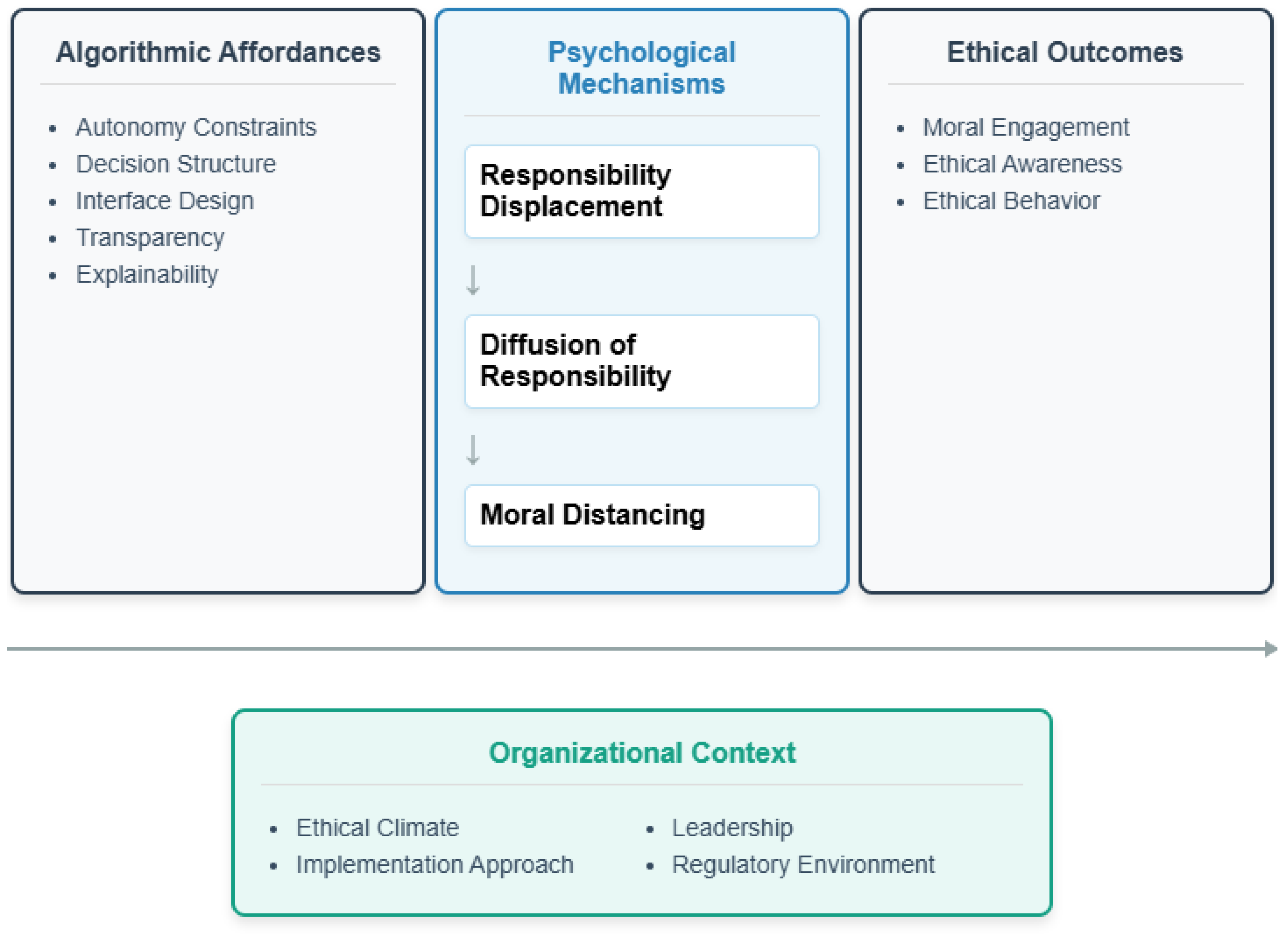

2.6. Conceptual Framework and Research Gaps

- Algorithmic Affordances: The features of algorithmic systems that enable or constrain particular actions and perceptions

- Psychological Mechanisms: The cognitive processes through which individuals engage or disengage from ethical dimensions of decisions

- Organizational Contexts: The social, cultural, and institutional environments in which algorithmic systems are implemented and used

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

- Quantitative Survey (N=187): Measuring perceived autonomy, moral engagement, and responsibility attribution in algorithm-mediated decisions

- Semi-structured Interviews (N=42): Exploring psychological mechanisms and contextual factors influencing responsibility perception

- Experimental Vignettes (N=134): Testing causal relationships between algorithmic constraints and ethical reasoning

3.2. Participants and Sampling

3.2.1. Sampling Strategy

- Financial services (loan officers and credit analysts, n=67)

- Healthcare (physicians and clinical decision-makers, n=73)

- Criminal justice (judges, attorneys, and probation officers, n=47)

- Size (small, medium, large institutions)

- Ownership structure (public, private, non-profit)

- Geographic location (urban, suburban, rural)

- Duration of algorithmic system implementation (1-2 years, 3-5 years, 5+ years)

3.2.2. Participant Characteristics

3.3. Data Collection

3.3.1. Quantitative Survey

- Perceived decision-making autonomy (α = .87): 8-item scale assessing the degree to which participants felt they had freedom and control in decision-making when using algorithmic systems (e.g., "I have significant freedom in how I use the algorithmic system's recommendations")

- Moral engagement (α = .82): 8-item scale measuring participants' level of ethical engagement when making algorithm-influenced decisions (e.g., "I feel personally responsible for the outcomes of decisions influenced by the algorithmic system")

- Responsibility attribution (α = .79): 8-item scale assessing how participants attributed responsibility for algorithm-influenced decisions (e.g., "If a decision based on the algorithmic system's recommendation has negative consequences, the system bears significant responsibility")

- Ethical awareness (α = .85): 8-item scale measuring awareness of ethical implications of algorithmic decisions (e.g., "I am aware of potential biases in the algorithmic system")

- Algorithm trust (α = .81): 8-item scale assessing participants' trust in algorithmic recommendations (e.g., "I trust the algorithmic system more than my own judgment for certain types of decisions")

3.3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

- Experiences with algorithmic decision systems

- Perceived responsibility for algorithm-influenced decisions

- Ethical reasoning processes when using algorithmic tools

- Organizational factors influencing responsibility perception

- Specific instances of ethical challenges with algorithmic systems

3.3.3. Experimental Vignettes

- Degree of algorithmic constraint (high vs. low)

- Transparency of algorithmic reasoning (transparent vs. opaque)

- Outcome valence (positive vs. negative)

3.4. Data Analysis

3.4.1. Quantitative Analysis

3.4.2. Qualitative Analysis

3.4.3. Experimental Analysis

3.4.4. Integration of Findings

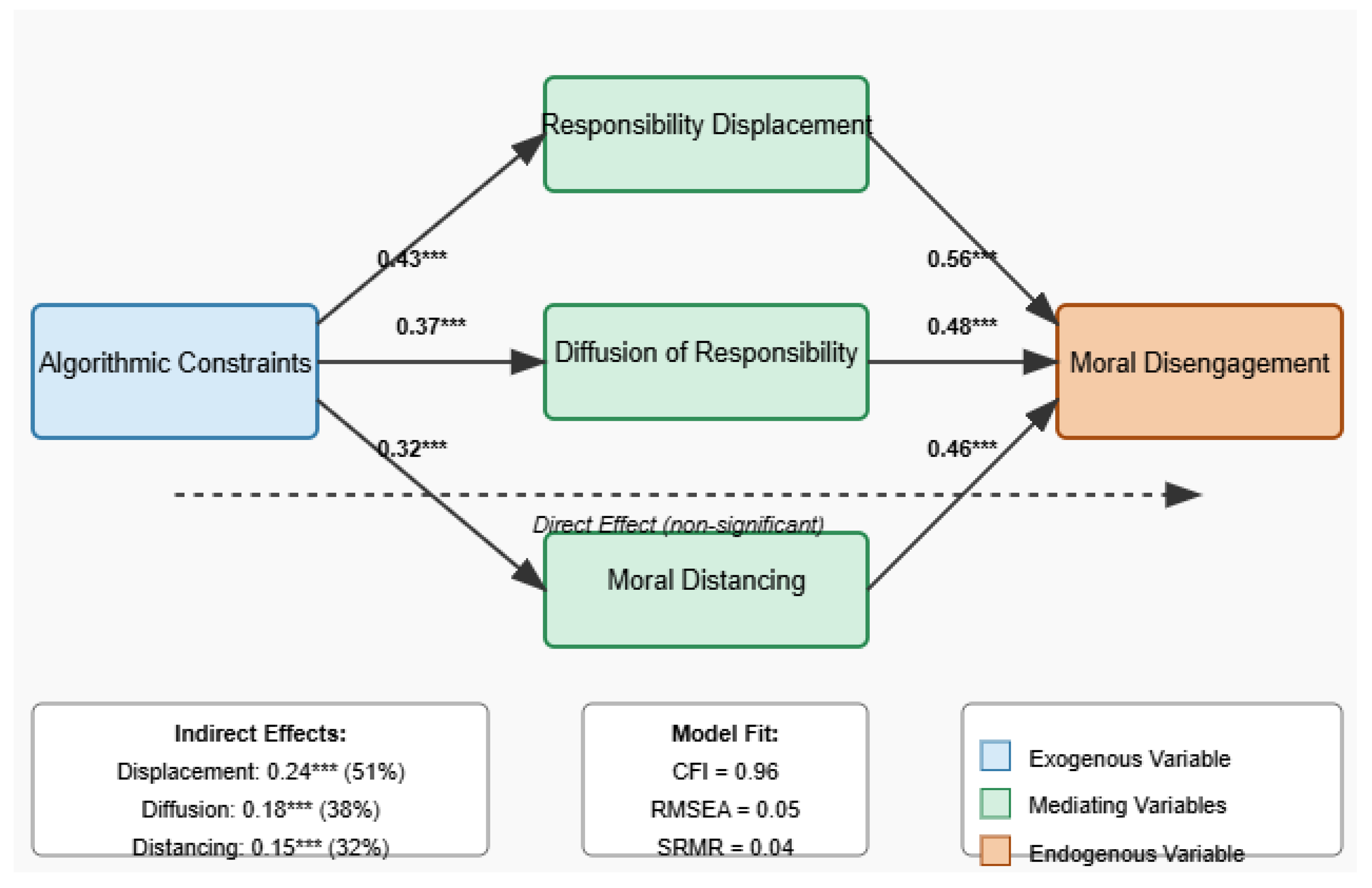

4. Results: Mechanisms of Algorithmic Moral Disengagement

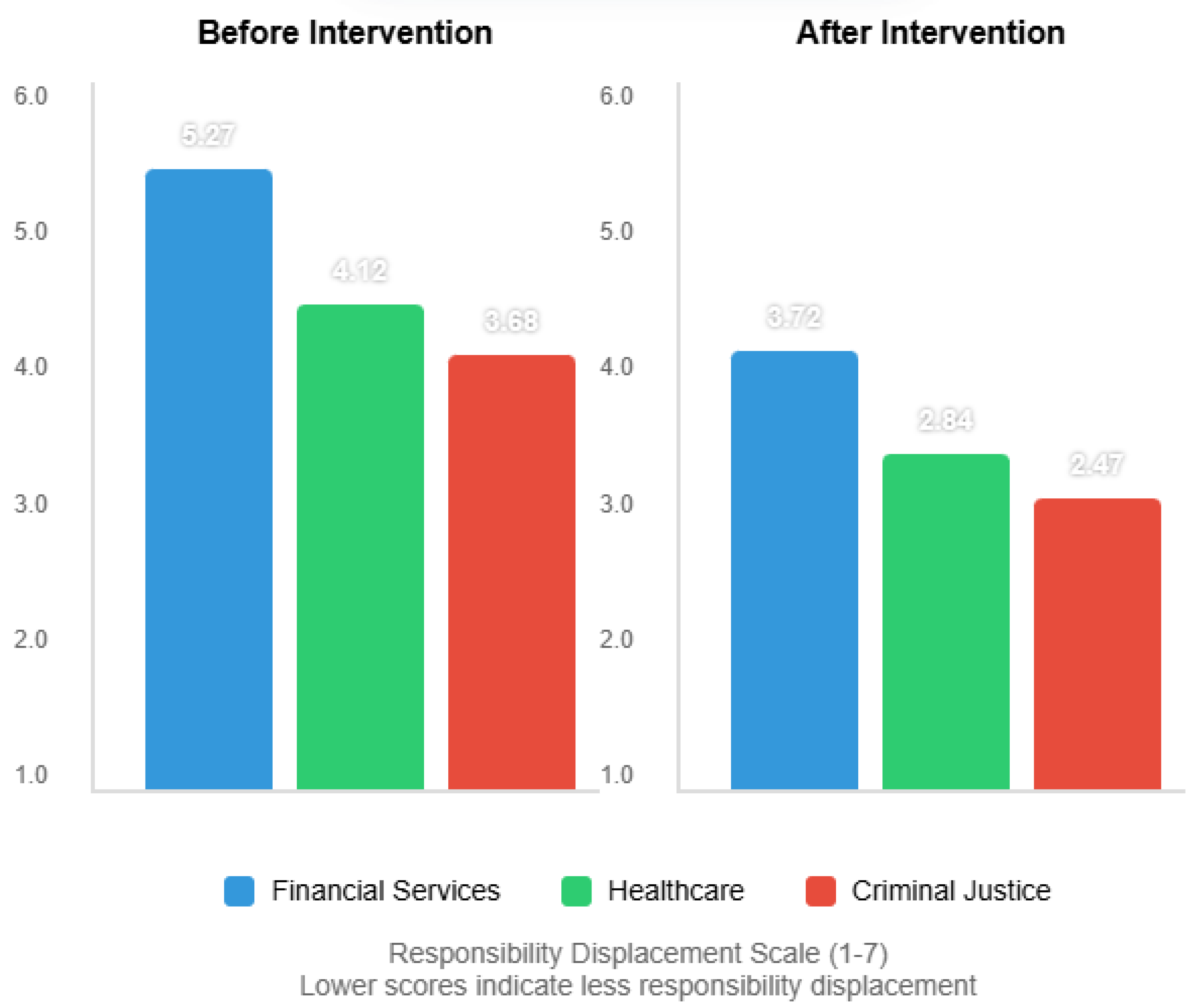

4.1. Responsibility Displacement

4.1.1. Quantitative Evidence

4.1.2. Qualitative Evidence

4.1.3. Experimental Evidence

4.2. Diffusion of Responsibility

4.2.1. Quantitative Evidence

4.2.2. Qualitative Evidence

4.2.3. Experimental Evidence

4.3. Moral Distancing

4.3.1. Quantitative Evidence

4.3.2. Qualitative Evidence

4.3.3. Experimental Evidence

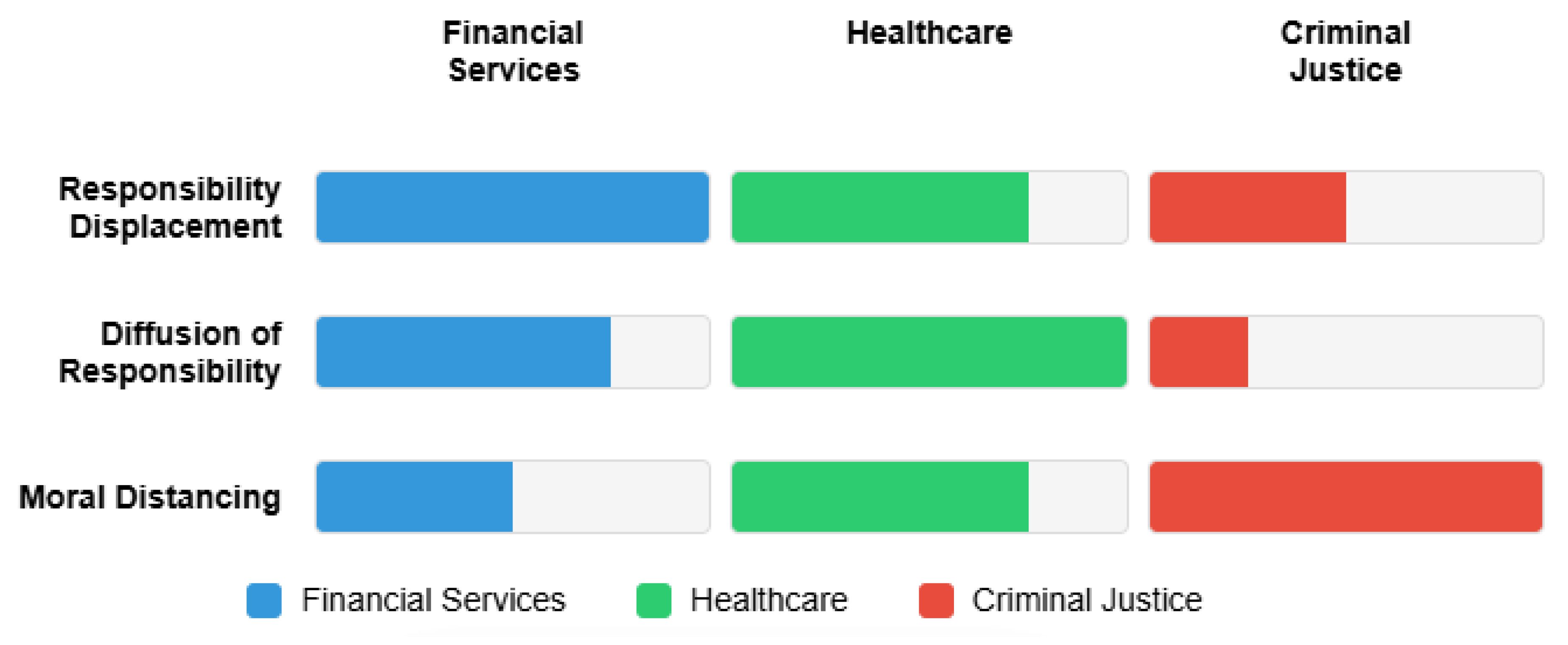

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Mechanisms

5. Sectoral Analysis: Context Matters

5.1. Financial Services: Algorithmic Credit Decisions

5.2. Healthcare: Clinical Decision Support and Physician Autonomy

5.3. Criminal Justice: Risk Assessment and Judicial Decision-Making

5.4. Cross-Sectoral Patterns and Regulatory Contexts

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.1.1. Extending Moral Disengagement Theory to Sociotechnical Systems

6.1.2. Ethical Buffer Zones in Sociotechnical Systems

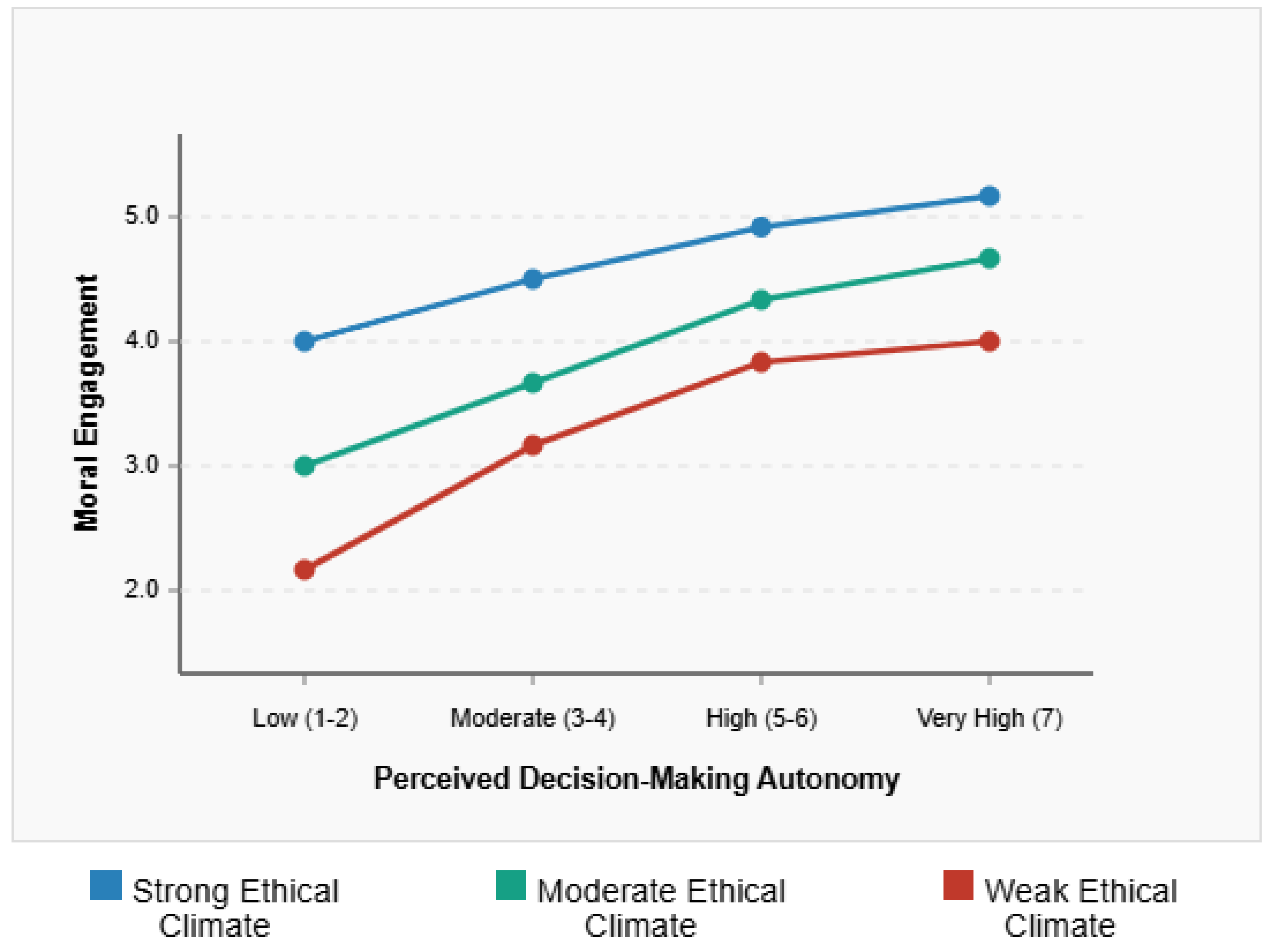

6.1.3. Contextual Moderation of Algorithmic Ethics

6.2. Practical Implications

6.2.1. Designing for Ethical Engagement

6.2.2. Implementing Meaningful Human Oversight

6.2.3. Creating Accountability Frameworks

- Explicit "responsibility mapping" that clarifies human and algorithmic roles

- Formal review processes for algorithmic decisions with adverse impacts

- Feedback mechanisms connecting decision-makers with outcome consequences

6.2.4. Cultivating Ethical Awareness

6.2.5. Implementation Challenges and Strategies

- Framing ethical engagement interventions in terms of risk management and quality improvement rather than solely as ethical imperatives

- Implementing interventions incrementally, starting with highest-risk decision contexts

- Developing domain-specific approaches to explainability that focus on contextually relevant factors

- Creating clear organizational incentives that reward ethical deliberation and thoughtful algorithm use

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

6.3.1. Methodological Limitations

6.3.2. Theoretical Limitations

6.3.3. Future Research Directions

- Longitudinal dynamics: How do patterns of moral engagement with algorithmic systems evolve over time? Do users develop resistance strategies or become more susceptible to moral disengagement with prolonged exposure?

- Design interventions: What specific design features most effectively promote ethical engagement? How can explainable AI approaches be tailored to support moral reasoning rather than simply providing technical explanations?

- Regulatory approaches: How do different regulatory frameworks influence patterns of moral engagement with algorithmic systems? Can regulation be designed to promote substantive ethical engagement rather than merely procedural compliance?

- Cultural variation: How do cultural differences in concepts of responsibility, authority, and technology influence algorithmic moral disengagement? Do the mechanisms identified in this study operate similarly across diverse cultural contexts?

- Affected perspectives: How do individuals subject to algorithmic decisions perceive responsibility and accountability? How do their perspectives align or conflict with those of professional users?

7. Conclusion

Appendix A. Survey Instrument and Interview Protocols

- In which sector do you primarily work?

- 2.

- What is your current job title? _____________

- 3.

- Gender:

- 4.

- Age range:

- 5.

- Years of professional experience in your current field:

- 6.

- How long have you been working with algorithmic decision systems in your professional role?

- 7.

- What type of algorithmic system do you most frequently use in your work? (Select all that apply)

- 8.

- How would you characterize the role of this algorithmic system in your decision-making?

- 9.

- How transparent is the algorithmic system you use?

- 10.

- I have significant freedom in how I use the algorithmic system's recommendations.

- 11.

- I feel constrained by the algorithmic system in my decision-making.

- 12.

- I can easily override the algorithmic system when I disagree with its recommendations.

- 13.

- My professional judgment takes precedence over the algorithmic system's recommendations.

- 14.

- I feel pressure to follow the algorithmic system's recommendations even when I disagree.

- 15.

- The algorithmic system limits my ability to use my professional expertise.

- 16.

- I have the final say in decisions that involve the algorithmic system.

- 17.

- The algorithmic system is designed to support rather than replace my judgment.

- 18.

- I carefully consider the ethical implications of decisions involving the algorithmic system.

- 19.

- I feel personally responsible for the outcomes of decisions influenced by the algorithmic system.

- 20.

- I regularly reflect on whether decisions involving the algorithmic system align with my professional values.

- 21.

- I am aware of how the algorithmic system might affect different stakeholders.

- 22.

- I actively consider alternative approaches when I have concerns about the algorithmic system's recommendations.

- 23.

- I feel engaged with the human impact of decisions influenced by the algorithmic system.

- 24.

- I consider myself morally accountable for decisions made with the algorithmic system's input.

- 25.

- I think critically about the values embedded in the algorithmic system.

- 26.

- When decisions involve the algorithmic system, responsibility is shared between me and the system.

- 27.

- If a decision based on the algorithmic system's recommendation has negative consequences, the system bears significant responsibility.

- 28.

- The developers of the algorithmic system are responsible for any unintended consequences of its recommendations.

- 29.

- My organization, rather than individual professionals, is responsible for outcomes of algorithmic decisions.

- 30.

- I am fully responsible for decisions I make, regardless of the algorithmic system's influence.

- 31.

- Following the algorithmic system's recommendations provides protection from criticism if things go wrong.

- 32.

- It would be unfair to hold me personally responsible for problematic outcomes resulting from the algorithmic system's recommendations.

- 33.

- When many people are involved in an algorithmic decision process, no one person bears full responsibility.

- 34.

- I am aware of potential biases in the algorithmic system.

- 35.

- I consider the ethical implications of my decisions when using the algorithmic system.

- 36.

- I think about how the algorithmic system might affect vulnerable populations.

- 37.

- I reflect on whether the algorithmic system aligns with principles of fairness and justice.

- 38.

- I consider how the algorithmic system might influence power dynamics in decision processes.

- 39.

- I am mindful of situations where algorithmic recommendations might lead to discriminatory outcomes.

- 40.

- I actively consider the long-term societal implications of algorithmic decision-making in my field.

- 41.

- I try to identify ethical dilemmas created by the use of algorithmic systems.

- 42.

- The algorithmic system generally makes good recommendations.

- 43.

- I trust the algorithmic system more than my own judgment for certain types of decisions.

- 44.

- The algorithmic system is based on sound principles and data.

- 45.

- The algorithmic system has proven reliable over time.

- 46.

- I am skeptical about the algorithmic system's recommendations.

- 47.

- The algorithmic system sometimes makes recommendations that seem arbitrary or wrong.

- 48.

- The algorithmic system has knowledge or capabilities that complement my own expertise.

- 49.

- I would feel comfortable defending the algorithmic system's recommendations to others.

- 50.

- My organization emphasizes ethical considerations in decision-making.

- 51.

- My supervisors expect me to follow the algorithmic system's recommendations.

- 52.

- My organization provides clear guidance on when to override algorithmic recommendations.

- 53.

- My colleagues regularly discuss ethical issues related to algorithmic systems.

- 54.

- My organization rewards efficiency over careful deliberation.

- 55.

- I received adequate training on the ethical use of algorithmic systems.

- 56.

- My organization has clear accountability processes for algorithmic decisions.

- 57.

- My organization values professional judgment over algorithmic recommendations.

- 58.

- How would you characterize the implementation of the algorithmic system in your organization?

- 59.

- Were you consulted during the design or implementation of the algorithmic system?

- 60.

- How would you rate your input into how the algorithmic system is used in your workflow?

- 61.

- Can you describe a specific situation where you felt conflicted about following the algorithmic system's recommendation? What did you do?

- 62.

- How has the algorithmic system changed how you think about your professional responsibilities?

- 63.

- What would make you more likely to take personal responsibility for decisions involving the algorithmic system?

- 64.

- Are there any other comments you would like to share about your experience with algorithmic systems in your professional role?

Appendix B. Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

- 1.

- Could you briefly describe your current professional role and responsibilities?

- 2.

- What types of algorithmic decision systems do you use in your work? How frequently do you interact with these systems?

- 3.

- How long have you been working with these algorithmic systems?

- 4.

- What training did you receive on using these systems?

- 5.

- Could you walk me through a typical scenario where you use the algorithmic system in your decision-making process?

- 6.

- How has the algorithmic system changed your decision-making process compared to before it was implemented?

- 7.

- Can you describe a situation where you disagreed with the algorithmic system's recommendation?

- 8.

- How do you feel when you override the system's recommendations?

- 9.

- When you make decisions using the algorithmic system, who do you see as responsible for the outcomes?

- 10.

- Has the algorithmic system changed how you think about your professional responsibilities?

- 11.

- Can you describe a situation where using the algorithmic system created an ethical dilemma for you?

- 12.

- How do you think about the ethical implications of decisions involving the algorithmic system?

- 13.

- How does your organization frame the purpose and role of the algorithmic system?

- 14.

- How does your organization handle situations where the algorithmic system makes errors or problematic recommendations?

- 15.

- How do discussions about the algorithmic system occur among your colleagues?

- 16.

- What organizational policies or practices influence how you use the algorithmic system?

- 17.

- What changes to the algorithmic system would make it more aligned with your professional values and responsibilities?

- 18.

- What advice would you give to someone in your field who is just starting to work with similar algorithmic systems?

- 19.

- Is there anything else about your experience with algorithmic systems that you think is important for me to understand that we haven't discussed?

- The degree of constraint imposed by the algorithmic system

- The transparency of the algorithmic system

- The outcome of the decision

- 1.

- To what extent do you feel personally responsible for the decision to decline the loan? (1-7 scale)

- 2.

- To what extent is each of the following responsible for the decision outcome:

- 3.

- How ethically problematic do you find this situation? (1-7 scale)

- 4.

- How satisfied are you with the decision process in this scenario? (1-7 scale)

- 5.

- What would you have done differently in this situation, if anything?

- 1.

- To what extent do you feel personally responsible for the decision to approve the mortgage? (1-7 scale)

- 2.

- To what extent is each of the following responsible for the decision outcome:

- 3.

- How ethically appropriate do you find this situation? (1-7 scale)

- 4.

- How satisfied are you with the decision process in this scenario? (1-7 scale)

- 5.

- What factors most influenced your sense of responsibility in this scenario?

- 1.

- To what extent do you feel personally responsible for the positive patient outcome? (1-7 scale)

- 2.

- To what extent is each of the following responsible for the decision outcome:

- 3.

- How ethically appropriate do you find this situation? (1-7 scale)

- 4.

- How satisfied are you with the decision process in this scenario? (1-7 scale)

- 5.

- How would you feel about using this system for future patients?

- 1.

- To what extent do you feel personally responsible for the negative patient outcome? (1-7 scale)

- 2.

- To what extent is each of the following responsible for the decision outcome:

- 3.

- How ethically problematic do you find this situation? (1-7 scale)

- 4.

- How satisfied are you with the decision process in this scenario? (1-7 scale)

- 5.

- What would you have done differently in this situation, if anything?

- 1.

- To what extent do you feel personally responsible for the sentencing decision? (1-7 scale)

- 2.

- To what extent is each of the following responsible for the decision outcome:

- 3.

- How ethically appropriate do you find this situation? (1-7 scale)

- 4.

- How satisfied are you with the decision process in this scenario? (1-7 scale)

- 5.

- What factors most influenced your sense of responsibility in this scenario?

- 1.

- To what extent do you feel personally responsible for the defendant's failure to appear? (1-7 scale)

- 2.

- To what extent is each of the following responsible for the decision outcome:

- 3.

- How ethically problematic do you find this situation? (1-7 scale)

- 4.

- How satisfied are you with the decision process in this scenario? (1-7 scale)

- 5.

- What would you have done differently in this situation, if anything?

- How the level of constraint imposed by algorithmic systems affects professionals' sense of responsibility

- How algorithmic transparency influences ethical evaluation and decision satisfaction

- How outcome valence (positive vs. negative) impacts responsibility attribution

References

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314-324.

- Ananny, M. , & Crawford, K. (2018). Seeing without knowing: Limitations of the transparency ideal and its application to algorithmic accountability. New Media & Society, 20(3), 973-989.

- Awad, E., Dsouza, S., Kim, R., Schulz, J., Henrich, J., Shariff, A., Bonnefon, J. F., & Rahwan, I. (2018). The moral machine experiment. Nature, 563(7729), 59-64.

- Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 164-180.

- Bandura, A. (2016). Moral disengagement: How people do harm and live with themselves. Worth Publishers.

- Barocas, S. , & Selbst, A. D. (2016). Big data's disparate impact. California Law Review, 104, 671-732.

- Benjamin, R. (2019). Race after technology: Abolitionist tools for the New Jim Code. Polity Press.

- Bijker, W. E. , Hughes, T. P., & Pinch, T. (2012). The social construction of technological systems: New directions in the sociology and history of technology. MIT Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Christin, A. (2017). Algorithms in practice: Comparing web journalism and criminal justice. Big Data & Society, 4(2), 1-14.

- Coeckelbergh, M. (2020). Artificial intelligence, responsibility attribution, and a relational justification of explainability. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(4), 2051-2068.

- Creswell, J. W. , & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Cummings, M. L. (2006). Automation and accountability in decision support system interface design. Journal of Technology Studies, 32(1), 23-31.

- Darley, J. M. , & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(4), 377-383.

- DiMaggio, P. J. , & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147-160.

- Dignum, V. (2019). Responsible artificial intelligence: How to develop and use AI in a responsible way. Springer Nature.

- Dodig-Crnkovic, G., & Persson, D. (2008). Sharing moral responsibility with robots: A pragmatic approach. In Proceedings of the 2008 Conference on Tenth Scandinavian Conference on Artificial Intelligence: SCAI 2008 (pp. 165-168). IOS Press.

- Elish, M. C. (2019). Moral crumple zones: Cautionary tales in human-robot interaction. Engaging Science, Technology, and Society, 5, 40-60.

- Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor. St. Martin's Press.

- Fjeld, J. , Achten, N., Hilligoss, H., Nagy, A., & Srikumar, M. (2020). Principled artificial intelligence: Mapping consensus in ethical and rights-based approaches to principles for AI. Berkman Klein Center Research Publication, 2020-1.

- Floridi, L. (2016). Faultless responsibility: On the nature and allocation of moral responsibility for distributed moral actions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 374(2083), 20160112.

- Friedman, B. , & Hendry, D. G. (2019). Value sensitive design: Shaping technology with moral imagination. MIT Press.

- Frith, C. D. (2014). Action, agency and responsibility. Neuropsychologia, 55, 137-142.

- Gogoll, J. , & Uhl, M. (2018). Rage against the machine: Automation in the moral domain. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 74, 97-103.

- Green, B., & Chen, Y. (2019). Disparate interactions: An algorithm-in-the-loop analysis of fairness in risk assessments. In Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 90-99). Association for Computing Machinery.

- Ihde, D. (1990). Technology and the lifeworld: From garden to earth. Indiana University Press.

- Johnson, D. G. (2006). Computer systems: Moral entities but not moral agents. Ethics and Information Technology, 8(4), 195-204.

- Kaminski, M. E. (2019). The right to explanation, explained. Berkeley Technology Law Journal, 34, 189-218.

- Klincewicz, M. (2019). Robotic nudges for moral improvement through Stoic practice. Techné: Research in Philosophy and Technology, 23(3), 425-455.

- Korsgaard, C. M. (2009). Self-constitution: Agency, identity, and integrity. Oxford University Press.

- Kroll, J. A. (2018). The fallacy of inscrutability. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 376(2133), 20180084.

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network theory. Oxford University Press.

- Leidner, B., Castano, E., Zaiser, E., & Giner-Sorolla, R. (2010). Ingroup glorification, moral disengagement, and justice in the context of collective violence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(8), 1115-1129.

- Logg, J. M. , Minson, J. A., & Moore, D. A. (2019). Algorithm appreciation: People prefer algorithmic to human judgment. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 151, 90-103.

- Martin, K. (2019). Ethical implications and accountability of algorithms. Journal of Business Ethics, 160(4), 835-850.

- Matthias, A. (2004). The responsibility gap: Ascribing responsibility for the actions of learning automata. Ethics and Information Technology, 6(3), 175-183.

- Miller, T. (2019). Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences. Artificial Intelligence, 267, 1-38.

- Mittelstadt, B. D. , Allo, P., Taddeo, M., Wachter, S., & Floridi, L. (2016). The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate. Big Data & Society, 3(2), 1-21.

- Moore, C. , & Gino, F. (2015). Approach, ability, aftermath: A psychological process framework of unethical behavior at work. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 235-289.

- Newman, G. E., Bullock, K., & Bloom, P. (2020). The psychology of delegating moral decisions to algorithms. Nature Communications, 11(5156), 1-10.

- Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

- Orlikowski, W. J. (2000). Using technology and constituting structures: A practice lens for studying technology in organizations. Organization Science, 11(4), 404-428.

- Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society: The secret algorithms that control money and information. Harvard University Press.

- Pinch, T. J. , & Bijker, W. E. (1984). The social construction of facts and artefacts: Or how the sociology of science and the sociology of technology might benefit each other. Social Studies of Science, 14(3), 399-441.

- Rest, J. R. , Narvaez, D., Thoma, S. J., & Bebeau, M. J. (1999). DIT2: Devising and testing a revised instrument of moral judgment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(4), 644-659.

- Schlenker, B. R., Britt, T. W., Pennington, J., Murphy, R., & Doherty, K. (1994). The triangle model of responsibility. Psychological Review, 101(4), 632-652.

- Seberger, J. S. , & Bowker, G. C. (2020). Humanistic infrastructure studies: Hyper-functionality and the experience of the absurd. Information, Communication & Society, 24(13), 1-16.

- Sharkey, A. (2017). Can robots be responsible moral agents? And why might that matter? Connection Science, 29(3), 210-216.

- Star, S. L. , & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, 'translations' and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387-420.

- Stevenson, M. T. (2018). Assessing risk assessment in action. Minnesota Law Review, 103, 303-384.

- Treviño, L. K. , den Nieuwenboer, N. A., & Kish-Gephart, J. J. (2014). (Un)ethical behavior in organizations. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 635-660.

- Vallor, S. (2015). Moral deskilling and upskilling in a new machine age: Reflections on the ambiguous future of character. Philosophy & Technology, 28(1), 107-124.

- van de Poel, I. , Royakkers, L., & Zwart, S. D. (2012). Moral responsibility and the problem of many hands. Routledge.

- Veale, M. , Van Kleek, M. , & Binns, R. (2018). Fairness and accountability design needs for algorithmic support in high-stakes public sector decision-making. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-14). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, P. P. (2005). What things do: Philosophical reflections on technology, agency, and design. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Wang, D. , Yang, Q. , Abdul, A., & Lim, B. Y. (2020). Designing theory-driven user-centric explainable AI. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-15). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, R. Y. (2020). Designing for grassroots food justice: A study of three food justice organizations utilizing digital tools. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 4(CSCW2), 1-28.

- Zarsky, T. (2016). The trouble with algorithmic decisions: An analytic road map to examine efficiency and fairness in automated and opaque decision making. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 41(1), 118-132.

| Characteristic | Financial Services (n=67) | Healthcare (n=73) | Criminal Justice (n=47) | Total (N=187) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 31 (46.3%) | 38 (52.1%) | 22 (46.8%) | 91 (48.7%) |

| Male | 35 (52.2%) | 34 (46.6%) | 25 (53.2%) | 94 (50.3%) |

| Non-binary | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.0%) |

| Age | ||||

| 25-34 | 18 (26.9%) | 12 (16.4%) | 7 (14.9%) | 37 (19.8%) |

| 35-44 | 26 (38.8%) | 29 (39.7%) | 16 (34.0%) | 71 (38.0%) |

| 45-54 | 15 (22.4%) | 21 (28.8%) | 14 (29.8%) | 50 (26.7%) |

| 55+ | 8 (11.9%) | 11 (15.1%) | 10 (21.3%) | 29 (15.5%) |

| Professional Experience | ||||

| 0-5 years | 13 (19.4%) | 9 (12.3%) | 5 (10.6%) | 27 (14.4%) |

| 6-10 years | 19 (28.4%) | 18 (24.7%) | 13 (27.7%) | 50 (26.7%) |

| 11-20 years | 24 (35.8%) | 32 (43.8%) | 18 (38.3%) | 74 (39.6%) |

| 21+ years | 11 (16.4%) | 14 (19.2%) | 11 (23.4%) | 36 (19.3%) |

| Algorithmic System Experience | ||||

| 0-1 year | 15 (22.4%) | 21 (28.8%) | 19 (40.4%) | 55 (29.4%) |

| 2-3 years | 31 (46.3%) | 35 (47.9%) | 20 (42.6%) | 86 (46.0%) |

| 4+ years | 21 (31.3%) | 17 (23.3%) | 8 (17.0%) | 46 (24.6%) |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 1. Perceived Autonomy | 3.42 | 1.18 | - | |||||||

| 2. Moral Engagement | 4.08 | 0.97 | .51** | - | ||||||

| 3. Responsibility Attribution | 3.89 | 1.05 | .47** | .62** | - | |||||

| 4. Ethical Awareness | 4.21 | 1.12 | .32** | .54** | .43** | - | ||||

| 5. Algorithm Trust | 3.76 | 0.89 | -.38** | -.21** | -.27** | -.12 | - | |||

| 6. Ethical Climate | 3.95 | 1.24 | .22** | .43** | .31** | .42** | .08 | - | ||

| 7. Implementation Approach† | 0.42 | 0.49 | .31** | .38** | .26** | .19* | -.14 | .22** | - | |

| 8. Algorithm Transparency | 3.12 | 1.32 | .34** | .39** | .35** | .28** | -.05 | .13 | .46** | - |

| 9. Responsibility Displacement | 4.32 | 1.28 | -.48** | -.59** | -.45** | -.48** | .42** | -.37** | -.33** | -.56** |

| 10. Responsibility Diffusion | 3.97 | 1.19 | -.35** | -.52** | -.41** | -.39** | .21** | -.29** | -.26** | -.42** |

| 11. Moral Distancing | 3.76 | 1.32 | -.41** | -.47** | -.36** | -.52** | .18* | -.24** | -.22** | -.38** |

| 12. Organizational Complexity | 4.34 | 1.06 | -.12 | -.08 | -.13 | -.04 | .15* | -.06 | -.11 | -.16* |

| 13. Interface Design Quality | 3.67 | 1.29 | .27** | .31** | .28** | .33** | .13 | .18* | .32** | .45** |

| Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| Control Variables | |||

| Age | .09 | .07 | .06 |

| Gender | .04 | .05 | .03 |

| Professional Experience | .12 | .08 | .05 |

| Algorithmic System Experience | -.05 | -.03 | -.02 |

| Sector - Healthcare† | .06 | .05 | .04 |

| Sector - Criminal Justice† | .15* | .12 | .08 |

| Main Effects | |||

| Perceived Autonomy | .47*** | .35*** | |

| Ethical Climate | .39*** | .31*** | |

| Algorithm Transparency | .26** | .18* | |

| Implementation Approach | .18* | .13* | |

| Interaction Terms | |||

| Autonomy × Ethical Climate | -.21** | ||

| Autonomy × Algorithm Transparency | -.17* | ||

| Autonomy × Implementation Approach | -.11 | ||

| R² | .05 | .39 | .46 |

| ΔR² | .34*** | .07** |

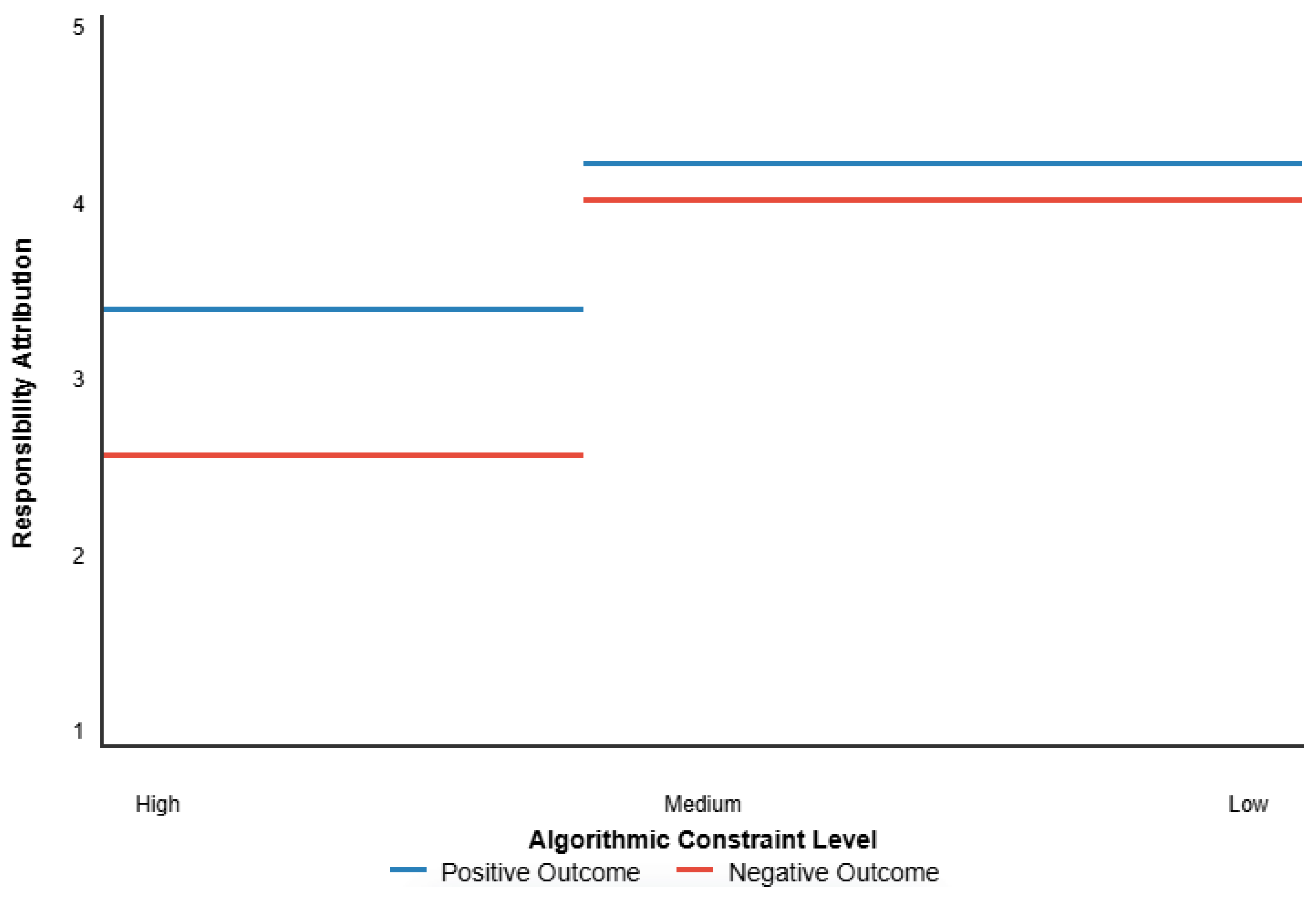

| Condition | Responsibility Attribution |

| Algorithmic Constraint Level | |

| High Constraint | 3.12 (0.78) |

| Low Constraint | 4.37 (0.82) |

| Algorithmic Transparency | |

| Transparent | 4.08 (0.91) |

| Opaque | 3.41 (0.84) |

| Outcome Valence | |

| Positive Outcome | 3.94 (0.87) |

| Negative Outcome | 3.55 (0.92) |

| Constraint × Outcome Interaction | |

| High Constraint, Positive Outcome | 3.46 (0.79) |

| High Constraint, Negative Outcome | 2.78 (0.65) |

| Low Constraint, Positive Outcome | 4.42 (0.84) |

| Low Constraint, Negative Outcome | 4.32 (0.81) |

| Sector | Mean Responsibility Displacement | Participatory Implementation | Top-down Implementation | p-value |

| Financial Services (n=67) | 5.27 (0.94) | 4.58 (0.87) | 5.81 (0.72) | < .001 |

| Healthcare (n=73) | 4.12 (1.08) | 3.42 (0.93) | 4.76 (0.85) | < .001 |

| Criminal Justice (n=47) | 3.68 (1.21) | 3.12 (1.14) | 4.17 (1.05) | < .01 |

| Total (N=187) | 4.41 (1.23) | 3.77 (1.13) | 4.96 (1.06) | < .001 |

| Intervention | Financial Services | Healthcare | Criminal Justice | Overall |

| Pre-recommendation reasoning requirement | 42% reduction | 51% reduction | 36% reduction | 47% reduction |

| Contextual explanations | 38% reduction | 33% reduction | 29% reduction | 34% reduction |

| Humanized presentation format | 24% reduction | 19% reduction | 31% reduction | 25% reduction |

| Responsibility mapping | 27% reduction | 31% reduction | 23% reduction | 28% reduction |

| Ethical awareness training | 29% reduction | 33% reduction | 35% reduction | 32% reduction |

| Outcome feedback mechanisms | 31% reduction | 37% reduction | 28% reduction | 33% reduction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).