Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Materials and Methods

- 1)

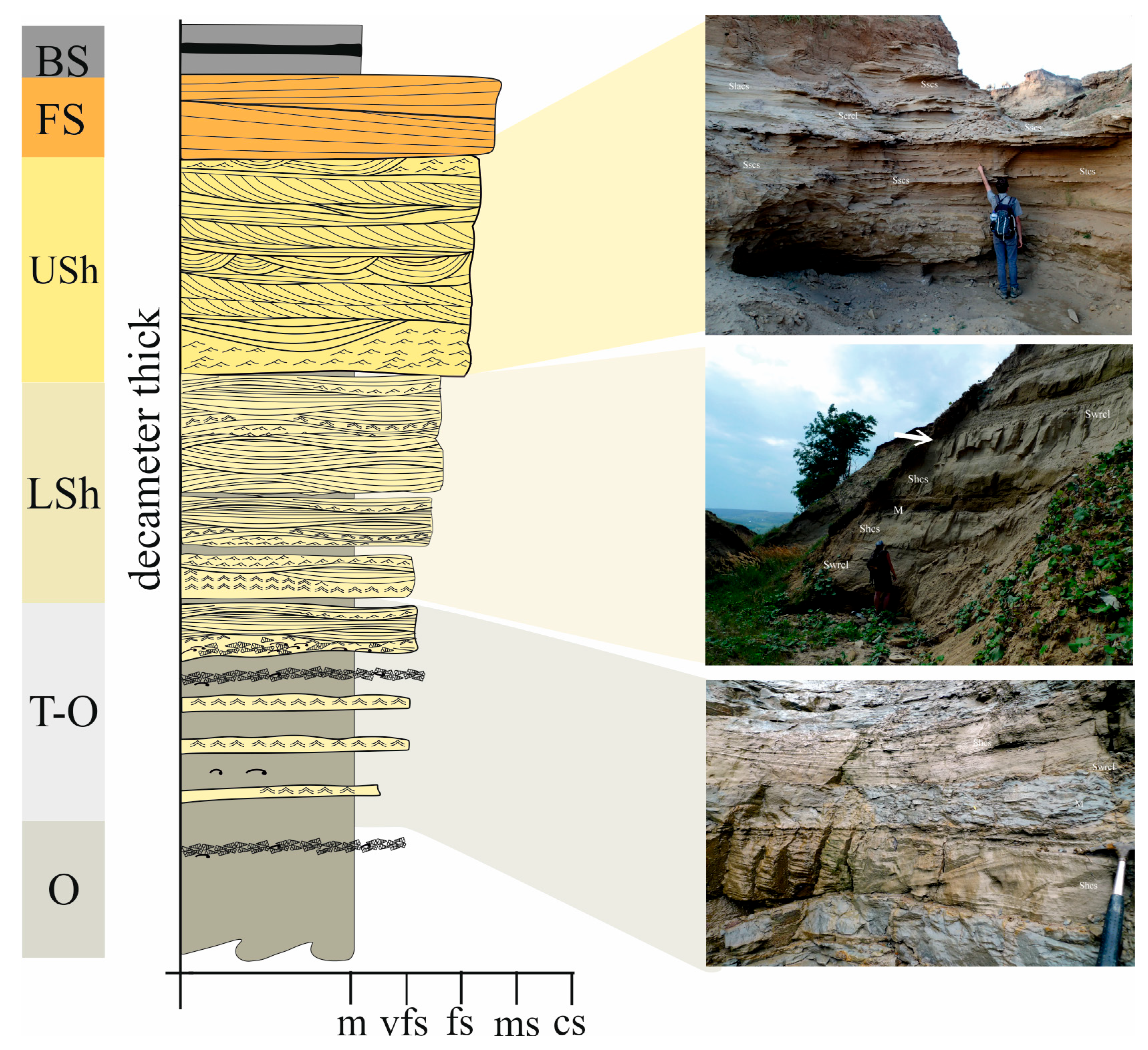

- Field analyses made in several field seasons during which detailed logs and sampling of outcrops were made in the Șomuz Formation stratotype area. Sedimentological investigations consisted in standard bed-by-bed logging after Nemec [33]’s methodology and photo shootings along Livijoara creek. A rough grouping of facies in facies associations was performed in the field, the latter being laterally traced on the photos where inaccessible. The descriptive sedimentological terminology is after [34,35,36,37] while for abbreviation we used the method of Miall [38] who uses capitals for lithology and smalls to abbreviate the sedimentary structure (e.g., Shcs means sands with hummocky cross stratification). Facies analysis and sedimentary process interpretation lead to the presented palaeodepositional environment interpretation based on existing facies models [39,40,41,42,43].

- 2)

- During sedimentary succession logging, several samples were collected for micro- and macrofauna analyses and photos were shot. Their fossil content, as well as the one known from previous papers (e.g., [28] was used for biostratigraphic age determination. The zonations proposed by [28,44,45,46,47], on the basis of molluscs, foraminifera and ostracods, were used. Some palaeoecological inferences were made taking in consideration the habitats of contemporary relatives of some taxa (molluscs and foraminifera).

- 3)

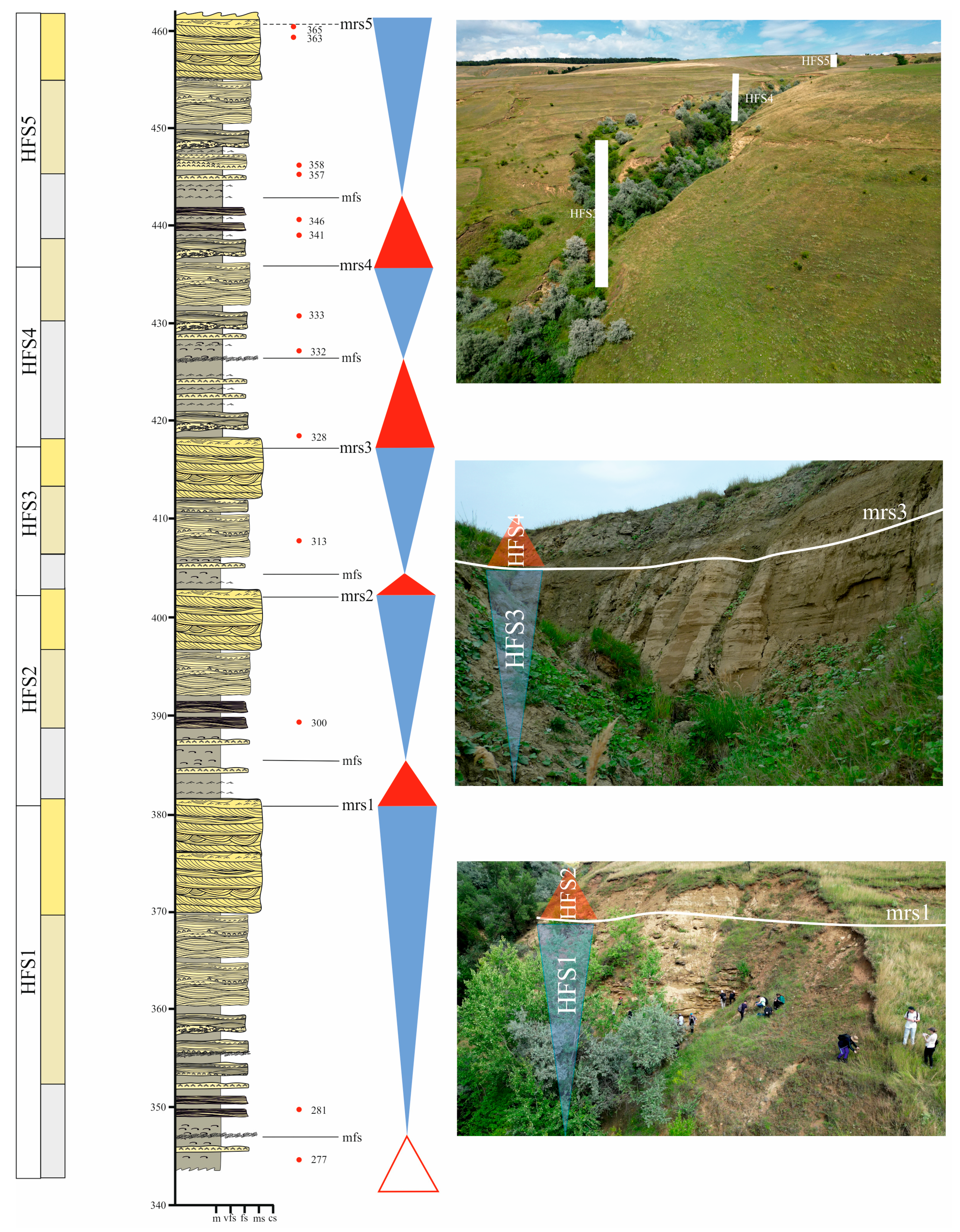

- The sedimentary succession was also studied by sequence stratigraphic point of view. For this purpose, we followed the terminology and model- and scale-independent work method especially useful at outcrop scale [48,49,50,51] where stratigraphic sequences are defined on the basis of their stratal stacking patterns and bounded by recurrent sequence stratigraphic surfaces irrespective of their allogenic or autogenic origin. Such a method can be applied at any temporal and space scale (form outcrop to seismic scale), allowing to avoid the confusions that can occur when the classic methods from the dawn of rather low-resolution seismic stratigraphy, proposed in 1970s-1980s, e.g., [52,53,54,55,56], are used. The data gathered from natural exposures have the disadvantage as being difficult to correlate, considering their sparsely distribution, as well as the possibility of estimating the extension significance of stratigraphic surfaces, being they local or regional. Accordingly, unconformities are considered here relevant sedimentologic hiatuses [51], even if they do not cover temporal gaps long enough to be biostratigraphically proven. We identified five decametre-thick sequences which we consider high frequency sequences (HFS).

4. Results

4.1. Biostratigraphic Data

4.2. Paleoecologic Inferences

4.3. Sedimentary Environments

4.4. High Frequency TR Sequences

5. Discussion

5.1. Paratethys Sea-Level Control on Accommodation

5.2. Tectonic Control on Accommodation

5.3. Controls on Sediment Supply

5.4. Cyclicity Modulator in the High Accommodation and Supply Area

6. Conclusions

- -

- The sedimentary succession represents the uppermost (ca 115 m) interval of a very thick (ca 1600 m) infill of the north part of Eastern Carpathians’ foredeep accumulated during their last major tectonic deformation (Moldavian tectogenesis).

- -

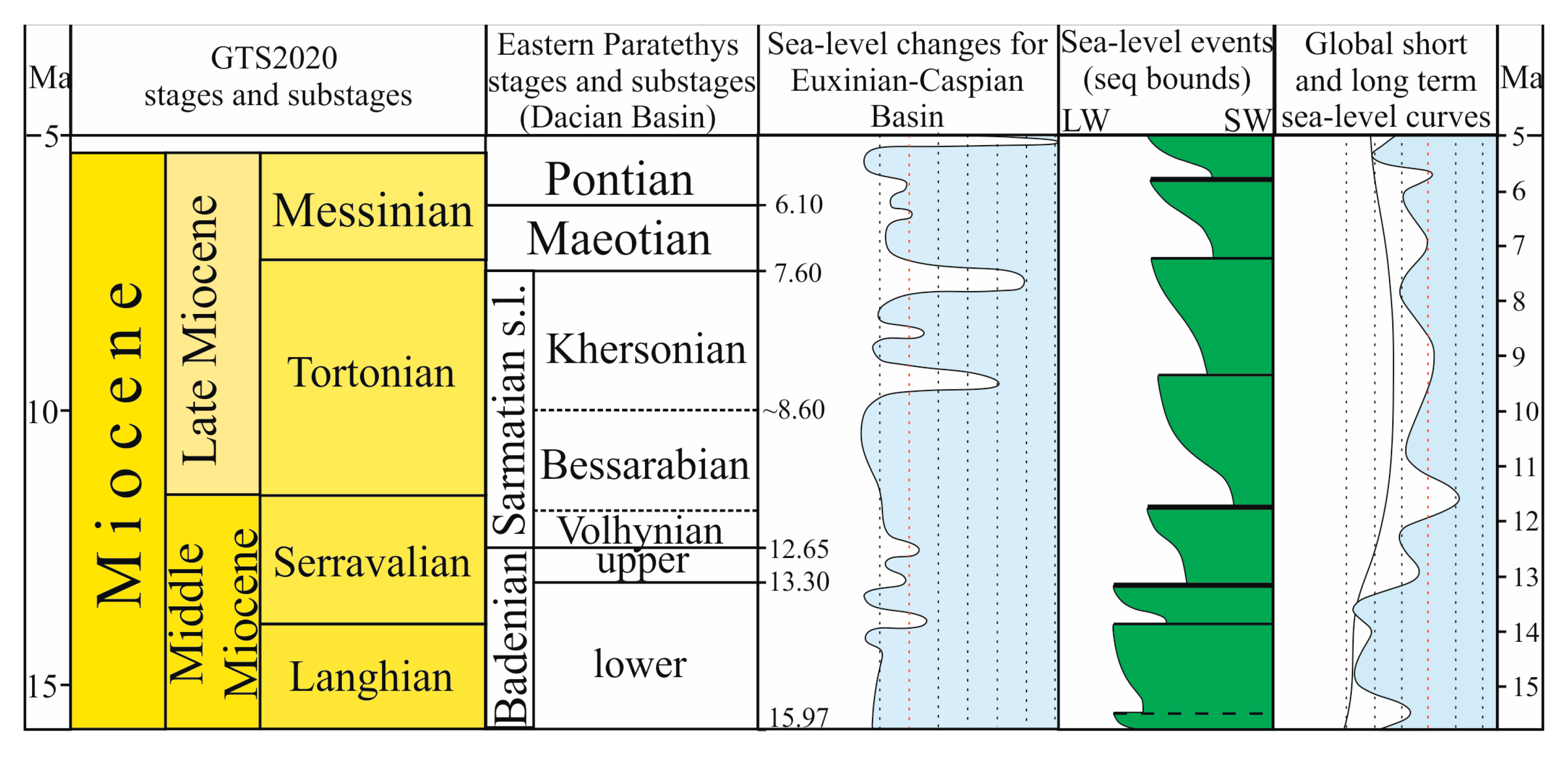

- Based on the molluscs, foraminifera, and ostracods, the sedimentary succession was biostratigraphically dated as uppermost Volhynian (the lower substage of the stage Sarmatian s.l., regionally defined for Eastern Paratethys).

- -

- The fossil content of the both studied interval and from several well sites (down to -1392 m) from neighbouring areas always indicate always shallow water, inner shelf (littoral to sublittoral) environments.

- -

- Three facies associations were defined, greyish-blue sandy mud and muddy sands with RCL of transition zone to offshore, sands with HCS of lower shoreface, and sands with TCS and SCS of upper shoreface, and interpreted as high-energy shoreface – transition to offshore, episodically affected by storms, sedimentary paleoenvironment.

- -

- The vertical recurrence of the three facies association allowed us to define five decametre – thick high frequency sequences (HFS1-5) bounded by maximum regressive surfaces, four of them mostly regressive, one transgressive-regressive types. The HFSs are at most of 4th rank and belongs to the (Volhynian – early Bessarabian, 3rd rank sequence, itself part of the Miocene 2nd rank sequence (“megacycle”).

- -

- The HFS sedimentation occurred in high accommodation setting where both foredeep high subsidence, a consequence of the major deformation of Eastern Carpathians in Volhynian, and Paratehys sea-level rise contributed. The high accommodation was balanced by a high sedimentation rate, so that the depositional environment remained shallow water.

- -

- The time span of the five HFSs was estimated as ca 75 kyr, from the ca 0.65 myr of Volhynian, on the basis of different evidences, each HFS lasting ca 15 kyr.

- -

- To explain the high frequency cyclicity on a high accommodation background at the space and time scale of HFSs we hypothesize as modulator the sediment supply controlled by precession climatic change in Carpathian source area.

- -

- Further studies are necessary in order to confirm the proposed control on cyclic sedimentation or to identify a better one.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rögl, V.F. Palaeogeographic considerations for Mediterranean and Paratethys seaways (Oligocene to Miocene). Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien 1999, 99A, 279–310. [Google Scholar]

- Steininger, F.H.; Wessely, G. From Tethyan Ocean to the Paratethys Sea: Oligocene to Neogene stratigraphy, palaeogeography and palaeobiology of the circum-Mediterranean region and the Oligocene to Neogene basin evolution in Austria. Mitt. Osterr. Geol. Ges. 1999, 92, 92–116. [Google Scholar]

- Seneš, J.; Marinescu, F. Cartes paléogéographiques du Néogène de la Paratéthys centrale. Memoires Bureau Recherches Géologiques et Minières 1974, 78, 785–792. [Google Scholar]

- Rusu, A. Oligocene events in Transylvania (Romania) and the first separation of Paratethys. D. S. Inst. Geol. Geofiz. 1988, 72–73, 207–223. [Google Scholar]

- Seneš, J. Entwicklungsphasen der Paratethys. Mitt. Geol. Gessell. (Wien) 1960, 52, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Harzhauser, M.; Landau, B.; Mandic, O.; Neubauer, T.A. The Central Paratethys Sea – rise and demise of a Miocene European marine biodiversity hotspot. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 16288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulea, E.; Popescu, I.; Sandulescu, J. Atlas litofaciesal. VI – Neogen; 1: 200 000. Institutul Geologic al României, București, Romania, 1969; map. [Google Scholar]

- Jipa, D.C.; Olariu, C. Dacian Basin. Depositional architecture and sedimentary history of a Paratethys Sea. Geo-Eco-Marina Special Publication no. 3, GeoEcoMar, București, Romania. 2009; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Leever, K.A.; Matenco, L.; Rabagia, T.; Cloethingh, S.; Krijgsman, W.; Stoica, M. Messinian sea level fall in the Dacic Basin (Eastern Paratethys): palaeogeographical implications from seismic sequence stratigraphy. Terra Nova 2010, 22, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, I.; Matenco, L.; Dinu, C.; Cloetingh, S. Effects of large sea-level variations in connected basins: the Dacian-Black Sea system of the Eastern Paratethys. Basin Research 2012, 0, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palcu, D.V.; Tulbure, M.; Bartol, M.; Kouwenhoven, T.J.; Krijgsman, W. Badenian-Sarmatian Extinction Even in the Carpathian foredeep of Romania: paleogeographic changes in the Paratethys domain. Global and Planetary Change 2015, 133, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palcu, D.V.; Vasiliev, I.; Stoica, M.; Krijgsman, W. The end of the Great Khersonian Drying of Eurasia: Magnetostratigraphic dating of the Maeotian transgression in the Eastern Paratethys. Basin Research 2019, 31, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoshko, A.; Matoshko, A.; de Leeuw, A.; Stoica, M. Facies analysis of the Balta Formation: Evidence for a large fluvio-deltaic system in the East Carpathian Foreland. Sedimentary Geology 2016, 343, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoshko, A.; de Leeuw, A.; Stoica, M.; Mandic, O.; Vasiliev, I.; Floroiu, A.; Krijgsman, W. The Mio-Pliocene transition in the Dacian Basin (Eastern Paratethys): paleomagnetism, mollusks, microfauna and sedimentary facies of the Pontian regional stage. Geobios 2023, 77, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miclӑuș, C. Geologia deltelor relicte extracarpatice sarmaţiene dintre văile Sucevei şi Bistriţei. PhD Thesis, “Al. I. Cuza” University, Iași, Romania, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grasu, C.; Miclӑuș, C.; Brânzilӑ, M.; Boboș, I. Sarmațianul din sistemul bazinelor de foreland ale Carpaților Orientali; Tehnicӑ, Ed.; București, Romania, 2002; p. 407. [Google Scholar]

- Miclӑuș, C.; Grasu, C.; Juravle, A. Sarmatian (middle Miocene) coastal deposits in the wedge-top depozone of the Eastern Carpathian foreland basin system. A case study. An. Șt. ale Univ. „Al.I. Cuza” din Iași, Seria Geologie 2011, 57, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Jipa, D.C. Large-scale along-arc sedimentary migration in the Carpathian foredeep. A paleogeographic approach. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 2018, 505, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionesi, L. Geologia unitӑților de platformӑ și a Orogenului Nord-Dobrogean; Tehnicӑ, Ed.; București, Romania, 1994; p. 280. [Google Scholar]

- Cobălcescu, G. Studii geologice şi paleontologice asupra unor tărâmuri terţiare din unele părţi ale României; Ed. Stabilimentul Grafic Socecü & Telcu, București, Romania, 1883; p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Simionescu, I. Contribuțiuni la geologia Moldovei dintre Siret și Prut. Publicațiunile fondului "V. Adamachi” 1903, 9, 73–116. [Google Scholar]

- Steininger, F.; Rögl, F. Paleogeography and palinspastic reconstruction of the Neogene of the Mediterranean and Paratethys. In The geological evolution of the eastern Mediterranean; Dixon, J.E., Robertson, A.H.F., Eds.; Special Publication of the Geological Society; Blackwell Sci. Publ., Oxford, UK, 1984; pp. 659–668. [Google Scholar]

- Vass, D. Numeric age of the Sarmatian boundaries (Seuss 1866). Slovak Geol. Mag. 1999, 5, 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Paghida-Trelea, N. Microfauna Miocenului dintre Siret și Prut; Ed. Academiei Române, București, Romania, 1969; p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Ionesi, L.; Ionesi, B.; Roșca, V.; Lungu, A.; Ionesi, V. Sarmațianul mediu și superior de pe Platforma Moldovenească; Ed. Academiei Române, București, România, 2005; p. 557. [Google Scholar]

- Ionesi, B. Cercetări geologice dintre Valea Sucevei și Pârâul Voitinel (Platforma Moldovenească). An. Șt. ale Univ. “Al. I. Cuza” din Iași 1969, 15, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Țibuleac, P. 1998. Studiul geologic al depozitelor sarmațiene din zona Fălticeni – Sasca – Răucești (Platforma Moldovenească) cu referire specială asupra stratelor de cărbuni. PhD Thesis, University „Alexandru Ioan Cuza” of Iași, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ionesi, V. Sarmațianul dintre Valea Siretului și Valea Șomuzului Mare; Ed. Universitӑții "Alexandru Ioan Cuza" Iași, Romania, 2006; p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- DeCelles, P.G.; Giles, K.A. Foreland basin systems. Basin Research 1996, 8, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulea, E. Geologie istoricӑ. Cap. IVB; In Geologie Istorică, Saulea, E., Ed.; Ed. Didacticӑ și Pedagogicӑ, București, Romania, 1967; pp. 621–735. [Google Scholar]

- Ionesi, L.; Ionesi, B. Asupra Vîrstei Nisipurilor de Văleni. An. Muz. Șt. Nat. Piatra Neamț, Seria Geologie-Geografie 1976, III, 139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ionesi, L.; Ionesi, B. Vue générale sur le Sarmatien des unités de plate-forme de Roumanie. In The Miocene from the Transylvanian Basin Romania; Bedelean, I., Meszaros, N., Nicorici, E., Petrescu, I., Eds.; Ed. Carpatica, Cluj-Napoca. Romania, 1994; pp. 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Nemec, W. Principles of lithostratigraphic logging and facies analysis. Short Course Compendium. Department of Earth Science, University of Bergen, 1996; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Harms, J.C.; Southard, J.B.; Spearing, D.R.; Walker, R.G. Depositional environments as interpreted from primary sedimentary structures and stratification sequences. SEPM Short Course no. 2., Dallas, USA, 1975; p. 161.

- Harms, J.C. Primary sedimentary structures. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1979, 7, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.R.L. Sedimentary Structures: Their Character and Physical Basis; Developments in Sedimentology 30B. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1984; Volume 2, p. 643. [Google Scholar]

- Collinson, J.D.; Thompson, D.B. Sedimentary structures, 2nd ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1989; p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Miall, A.D. Lithofacies types and vertical profile models in braded river deposits: A summary. Geological Survey of Canada 1977, 5, 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.H. Shelf and shallow marine sands. In Facies Models, 2nd ed.; Walker, R.G., Ed.; Geological Association of Canada, Canada, 1984; pp. 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.G.; Plint, A.G. Wave- and storm-dominated shallow marine systems. In Facies Models. Response to sea level change; Walker, R.G., James, N.P., Eds.; Geological Association of Canada, Love Printing Service Ltd., Stittsville, Ontario, Canada, 1992; pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Reading, H.G.; Collinson, L.D. Clastic coasts. In Sedimentary environments: Processes, Facies, and Stratigraphy, 3rd ed.; Reading, H.G., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 152–280. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, F.E. A reexamination of facies models for clastic shorelines. In Facies Models Revisited; Posamentier, H.W., Walker, R.G., Eds.; SEPM Special Publ. 84, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA, 2006; pp. 293–337. [Google Scholar]

- Plint, A.G. Wave- and storm-dominated shoreline and shallow-marine systems. In Facies Models 4; James, N.P., Dalrymple, R.W., Eds.; Geological Association of Canada, GEO text 6, Marquis Book Printing Inc., Canada, 2010; pp. 167–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ionesi, B. Stratigrafia depozitelor miocene de platformӑ dintre Valea Siretului și Valea Moldovei; Ed. Academiei Române, București, Romania, 1968; p. 395. [Google Scholar]

- Ionesi, B. , 1991. Biozonation of the Sarmatian from Moldavian Platform. The celebration days of “Al. I. Cuza” University of Iași (25–26 Oct. 1991) – conference paper.

- Kojumdgieva, E.I.; Paramonova, N.P.; Belokrys, L.S.; Muskhelishvili, L.V. Ecostratigraphic subdivision of the Sarmatian after mollusks. Geologica Carpathica 1989, 40, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jiříček, R.; Říha, J. Correlation of Ostracod Zones in the Paratethys and Tethys. In Shallow Tethys 3: Proceedings of the Internatioanal Symposium on Shallow Tethys 3; Kotaka, T., Ed.; Saito Höonkai: The Saito Gratitude Foundation, Sendai, Japan, 1991; pp. 435–457. [Google Scholar]

- Catuneanu, O.; Galloway, W.E.; Kendall, C.G.S.C.; Miall, A.D.; Posamentier, H.W.; Strasser, A.; Tucker, M.E. Sequence stratigraphy: Methodology and nomenclature. Newsl. Stratigr. 2011, 44, 173–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catuneanu, O.; Zechin, M. High-resolution sequence stratigraphy of clastic shelves II: controls on sequence development. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2013, 39, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catuneanu, O. Model-independent sequence stratigraphy. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 188, 312–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catuneanu, O. Scale in sequence stratigraphy. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 106, 128–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vail, P.R.; Mitchum, R.M.Jr.; Thompson, S. Seismic stratigraphy and global changes of sea level, Part 3: Relative changes of sea level from coastal onlap. In Seismic Stratigraphy—Applications to Hydrocarbon Exploration; Payton, C.E., Ed.; AAPG Memoir 26; AAPG: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1977; pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Vail, P.R.; Todd, R.G.; Sangree, J.B. Seismic stratigraphy and global changes of sea level, Part 5. Chronostratigraphic significance of Seismic Reflections: Section 2. Application of Seismic reflection configuration to stratigraphic interpretation. In Seismic Stratigraphy—Applications to Hydrocarbon Exploration; Payton, C.E., Ed.; AAPG Memoir 26; AAPG: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1977; pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Jervey, M.T. Quantitative geological modeling of siliciclastic rock sequences and their seismic expression. In Sea—Level Changes: An Integrated Approach; Wilgus, C.K., Hastings, B.S., Kendall, C.G.S.C., Posamentier, H.W., Ross, C.A., Van Wagoner, J.C., Eds.; SEPM Special Publication: Claremore, OK, USA, 1988; Volume 42, pp. 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Posamentier, H.; Vail, P.R. Eustatic controls on clastic deposition II—Sequences and systems tract models. In Sea Level Changes—An Integrated Approach; Wilgus, C.K., Hastings, B.S., Posamentier, H., Van Wagoner, J., Ross, C.A., Kendall, C.G.S.C., Eds.; SEPM Special Publication: Claremore, OK, USA, 1988; Volume 42, pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagoner, J.C.; Posamentier, H.W.; Mitchum, R.M.; Vail, P.R.; Sarg, T.S.; Loutit, T.S.; Hardenbol, J. On overview of the fundamentals of sequence stratigraphy and key definitions. In Sea—Level Changes: An Integrated Approach; Wilgus, C.K., Hartings, B.S., Posamentier, H., Van Wagoner, J., Ross, C.A., Kendall, C.G.S.C., Eds.; SEPM Special Publication: Claremore, OK, USA, 1988; Volume 42, pp. 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kojumdgeva, E. Les fosiles de Bulgarie. VIII, Sarmatien; Izd. na Lulg. Akad. na Nauk., Sofia, Bulgaria, 1969; p. 223.

- Harzhauser, M.; Guzhov, A.; Landau, B. A revision and nomenclator of the Cainozoic mudwhelks (Mollusca: Caenogastropoda: Batillariidae, Potamididae) of the Paratethys Sea (Europe, Asia). Zootaxa 5272(1), Magnolia Press, Auckland, New Zeeland, 2023; pp. 241.

- Signorelli. J.H. Catalogue of fossil genera of Mactridae (Mollusca: Bivalvia). Journal of Palaeontology 2023, 97, 823–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitriu, S.D.; Loghin, S.; Dubicka, Z.; Melinte–Dobrinescu, M.C.; Paruch–Kulczycka, J.; Ionesi, V. Foraminiferal, ostracod, and calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy of the latest Badenian–Sarmatian interval (Middle Miocene, Paratethys) from Poland, Romania and Republic of Moldova. Geologica Carpathica 2017, 68, 419–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M. Mittelmiozane Ostracoden aus dem Wiener Becken (Badenium/Sarmatium, Österreich). Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien, Österreich, 2006; p. 224.

- Aiello, G.; Szczechura, J. Middle Miocene ostracods of the Fore-Carpathian Depression (Central Paratethys, Southwestern Poland). Bolletino della Società Paleontologica Italiana 2004, 43, 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ionesi, B.; Chintӑuan, I. Studiul ostracodelor din depozitele volhiniene de pe Platforma Moldoveneascӑ (Sectorul dintre Valea Siretului și Valea Moldovei). D.S. Inst. Geol. Geofiz (1973-1974) 1975, LXI, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Loghin, S. Domenii depoziționale și asiociații microfaunistice din partea centralӑ a forelandului Carpaților Orientali. PhD Thesis, “Al.I. Cuza” University, Iași, Romania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Semeniuk, V.; Cresswell, I. Species Zonation. In Encyclopedia of Estuaries; Kennish, M.J., Ed.; Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series, Springer, Dordrecht, 2016; pp. 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Valle, P.; Nicoletti, L.; Finoia, M.G.; Ardizzone, G.D. Donax trunculus (Bivalvia: Donacidae) as a potential biological indicator of grain-size variations in beach sediment. Ecological Indicators 2011, 11, 1426–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocean Biodiversity Information System. Available online: https://obis.org/taxon/246150 (accessed on 13.03.2025).

- Smith, D.A.S. Some aspects of the biology of Gibbula cineraria (L.) with observations on Gibbula umbilicalis (DaCosta) and Gibbula pennanti (Phil.). (Mollusca: Prosobranchia). PhD Thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Ionesi, B.; Guevara, I. Studiul depozitelor sarmațiene din forajul 1002 Bӑdeuți (NV Platformei Moldovenești). Bul. Soc. Geol. Rom. 1993, 14, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, M.R. Epiphytic foraminifera. Marine Micropaleontology 1993, 20, 235–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.W. Ecology and applications of benthonic foraminifera; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006; p. 426. [Google Scholar]

- Peryt, D.; Gedl, P. Palaeoenvironmental changes preceding the Middle Miocene Badenian salinity crisis in the northern Polish Carpathian Foredeep Basin (Borków quarry) inferred from foraminifers and dinoflagellate cysts. Geological Quarterly 2010, 54, 487–508. [Google Scholar]

- Filipescu, S.; Miclea, A.; Gross, M.; Harzhauser, M.; Zagorsek, K.; Jipa, C. Early Sarmatian paleoenvironments in the easternmost Pannonian Basin (Borod Depression, Romania) revealed by the micropaleontological data. Geologica Carpathica 2014, 65, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreisa, R.D.; Bambach, R.K. The role of storm processes in generating shell beds in Paleozoic shelf environments. In Cyclic and Event Stratification; Einsele, G., Seilacher, A, Eds.; Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 1982; pp. 200–207. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, T.; Razin, P.; Faugeres, J.-C. Hummocky cross-stratification-like structures in deep-sea turbidites: Upper Cretaceous Basque basins (Western Pyrenees, France. Sedimentology 2009, 56, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsilli, M.; Pomar, L. Internal waves vs. Surface storm waves: a review on the origin of hummocky cross-stratification. Terra Nova 2012, 24, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckie, D.A.; Walker, R.G. Storm- and tide-dominated shorelines in Cretaceous Moosebar-Lower Gates interval – Outcrop equivalents of deep basin gas trap in Western Canada. AAPG Bull. 1982, 66, 138–157. [Google Scholar]

- Dott, R.H.; Bourgeois, J. Hummocky stratification: significance of its variable bedding sequences. GSA Bull. 1982, 93, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheel, R.J. Grain fabric in hummocky cross-stratified storm beds: genetic implications. J. Sediment. Petrol. 1991, 61, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheel, R.J.; Leckie, D.A. Hummocky cross-stratification. In Sedimentology Review 1; Wright, V.P., Ed.; Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P.A. Hummocky cross-stratification is not produced purely under progressive gravity waves. Nature 1985, 313, 562–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, D.J.P.; Figueiredo JR., A. G. ; Freeland, G.L.; Oertel, G.F. Hummcky cross-stratification and megaripples: a geological double standard?; J. Sedim. Petrol. 1983, 4, 1295–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, W.L.; Arnott, R.W.C.; Cheel, R.J. Shelf sandstones and hummocky cross-stratification: new insights on a stormy debate. Geology 1991, 19, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, R.W.; Southard, J.B. Exploratory flow-duct experiments on combined-flow bed configurations, and some implications for interpreting storm-event stratification. J. Sedim. Petrol. 1990, 60, 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, S.; Arnott, R.W.C.; Southard, J.B. Experiments on oscillatory flow and combined flow bed forms: implications for interpreting parts of the shallow-marine sedimentary record. J. Sedim. Petrol. 2005, 75, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, S.; Arnott, R.W.C. Origin of hummocky and swalley cross-stratification – The controlling influence of unidirectional current strength and aggradation rate. Geology 2006, 34, 1073–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, W.L. Hummocky cross-stratification, tropical hurricanes, and intense winter storms. Sedimentology 1985, 32, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, R.W.C. Ripple cross-stratification in swalley cross-stratified sandstones of the Chungo Member, Mount Yamnuska, Alberta. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1992, 29, 1802–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrow, P.M. Bypass-zone tempestite facies model and proximality trends for ancient muddy shoreline and shelf. J. Sedim. Petrol. 1992, 62, 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Komar, P.D. Beach processes and sedimentation. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA, 1976; p. 429.

- Collinson, J. Sedimentary deformational structures. In The geological deformation of sediments; Maltman, A., Ed.; Chapman & Hall: London, United Kingdom, 1994; pp. 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- Catuneanu, O. Principles of Sequence Stratigraphy, 2nd Ed. ed; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2022; p. 486. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.G.; Murphy, M.A. , Time-rock model for Siluro-Devonian continental shelf, Western United States. GSA Bull. 1984, 95, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionesi, L.; Ionesi, B. Contributions à l’étude du Buglovien d’entre Baseu et Prut (Platforme Moldave). An. Șt. Univ.”Al. I. Cuza” Iași, Geol.–Geogr. 1982, 2, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Harzhauser, M.; Piller, W.E. Integrated stratigraphy of the Sarmatian (Upper Middle Miocene) in the western Central Paratethys. Stratigraphy 2004, 1, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matenco, L.; Andriessen, P.; SourceSink Network. Quantifying the mass transfer from mountain ranges to deposition in sedimentary basins: Source to sink studies in the Danube Basin–Black Sea system. Global and Planetary Change 2013, 103, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, S.V.; Antipov, M.P.; Zastrozhnov, A.S.; Kurina, E.E.; Pinchuk, T.N. Sea level fluctuations on the northern shelf of the Eastern Paratethys in the Oligocene-Neogene. Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation 2010, 18, 200–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, B.U.; Ogg, J.G. Retraversing the highs and lows of Cenozoic Sea levels. GSA Today 2024, 34, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sӑndulescu, M. Cenozoic history of the Carpathians. AAPG Memoir 1988, 45, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Roure, F.; Roca, E.; Sassi, W. The Neogene evolution of the outer Carpathian flysch units (Poland, Ukraine and Romania): kinematics of a foreland /fold-and-thrust belt system. Sedimentary Geology 1993, 86, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matenco, L. Tectonic evolution of the Outer Romanian Carpathians: Constrains from kinematic analysis ad flexural modelling. PhD Thesis, Vrije University, Faculty of Earth Sciences, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, C.A.E.; Andreiessen, P.A.M.; Cloething, S.A.P.L. Life cycle of the East Carpathian orogen: erosion history of a doubly vergent critical wedge assessed by fission track thermochronology. Journal of Geophysical Research 1999, 104, 29095–29112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mațenco, L.; Krézsek, C.; Merten, S.; Schmid, S.; Cloetingh, S.; Andriessen, P. Characteristics of collisional orogens with low topographic build-up: an example from the Carpathians. Terra Nova 2010, 22, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.A. Time scales of tectonic landscapes and their sediment routing systems. In Landscape evolution: denudation, climate and tectonics over different time and space scales; Gallagher, K., Jones, S.J., Wainwright, J., Eds.; Geological Society Special Publications: London, UK, 2008; 296, pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zachos, J.; Pagani, M.; Sloan, L.; Thomas, E.; Billups, K. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to Present. Science 2001, 292, 686–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliev, I.; de Leeuw, A.; Filipescu, S.; Krijgsman, W.; Kuiper, K.; Stoica, M.; Briceag, A. The age of the Sarmatian-Pannonian transition in the Transylvanian Basin (Central Paratethys). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Paleoecology 2010, 297, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, E.W.; Harzhauser, M.; Mandic, O. Miocene Central Paratethys stratigraphy – current status and future directions. Stratigraphy 2007, 4, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffi, I.; Wade, B.S.; Pälike, H.; Beu, A.G.; Cooper, R.; Crundwell, M.P.; Krijgsman, W.; Moore, T.; Raine, I.; Sardella, R.; Vernyhorova, Y.V. The Neogene Period. In Geological Time Scale 2020; Gradstein, F.M., Ogg, J.G., Schmitz, M.D., Ogg, G.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2020; Volume I, pp. 1141–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Ohneiser, C.; Acton, G.; Channell, J.E.T.; Wilson, G.S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamazaki, T. A middle Miocene relative paleointensity record from the Equatorial Pacific. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2013, 374, 277–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).