Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

“Science is a collaborative effort. The combined results of several people working together is often much more effective than an individual scientist working alone.”

—John Bardeen1

1.1. Scope and Comparison to Other Surveys

1.2. Paper Organization

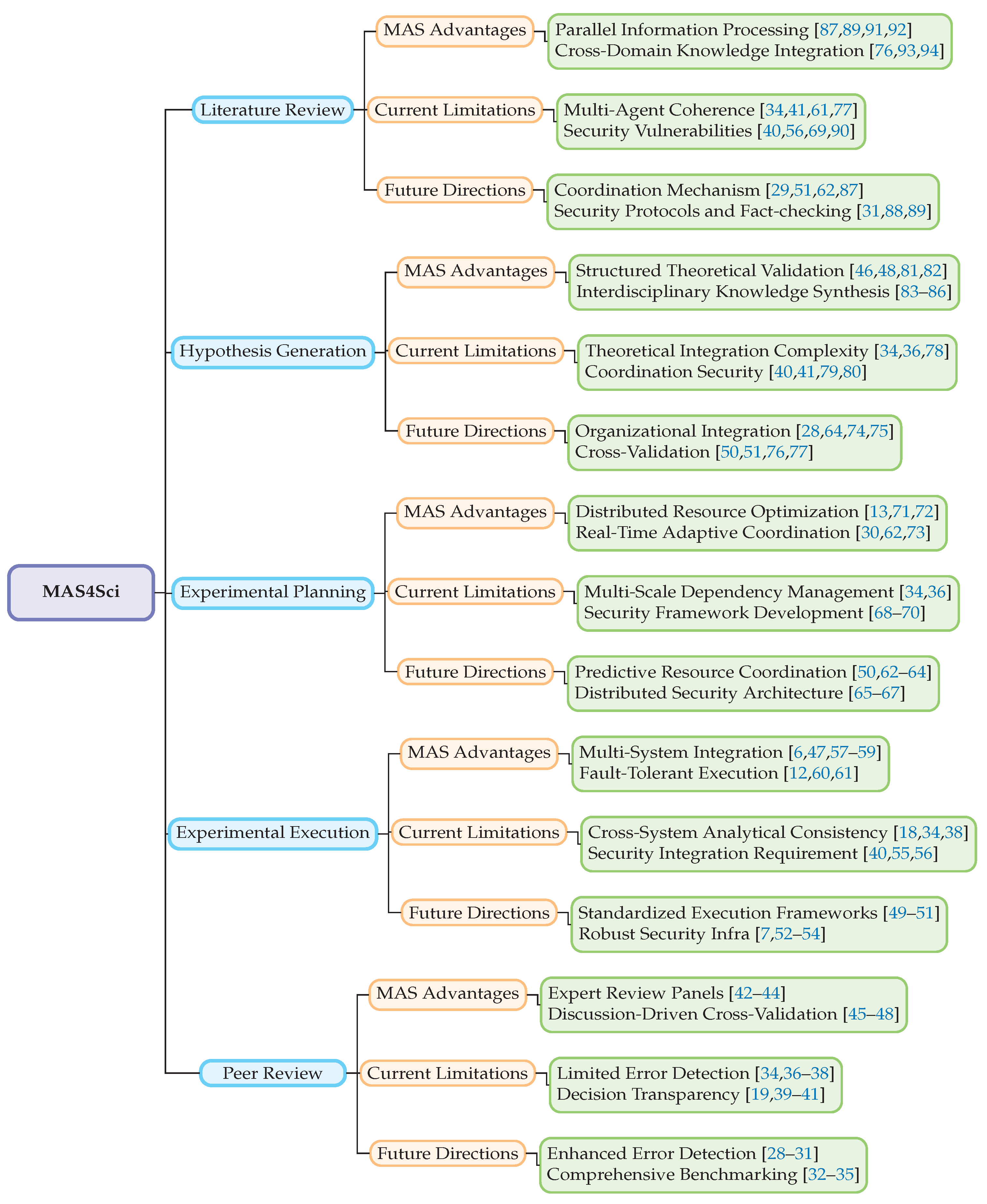

2. Multi vs. Single Agent across Key Stages in Scientific Research Workflow

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Hypothesis Generation

2.3. Experimental Planning

2.4. Experimental Execution

2.5. Peer Review

3. Current Reality and Key Bottlenecks

3.1. Literature Review

3.2. Hypothesis Generation

3.3. Experimental Planning

3.4. Experimental Execution

3.5. Peer Review

4. Future Work Towards MAS4Science

4.1. Literature Review

4.2. Hypothesis Generation

4.3. Experimental Planning

4.4. Experimental Execution

4.5. Peer Review

5. Vision and Conclusions

6. Limitations

6.1. References and Methods

6.2. Empirical Conclusions

6.3. Ethical Considerations

References

- King, R.; Whelan, K.E.; Jones, F.; Reiser, P.G.K.; Bryant, C.H.; Muggleton, S.; Kell, D.; Oliver, S. Functional genomic hypothesis generation and experimentation by a robot scientist. Nature 2004, 427, 247–252.

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [CrossRef]

- DeepMind, G. AI achieves silver-medal standard solving International Mathematical Olympiad problems, 2024.

- Xu, X.; Bolliet, B.; Dimitrov, A.; Laverick, A.; Villaescusa-Navarro, F.; Xu, L.; Íñigo Zubeldia. Evaluating Retrieval-Augmented Generation Agents for Autonomous Scientific Discovery in Astrophysics. arXiv preprint 2025, [2507.07155].

- Wang, H.; Fu, T.; Du, Y.; Gao, W.; Huang, K.; Liu, Z.; Chandak, P.; Liu, S.; Katwyk, P.V.; Deac, A.; et al. Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature 2023, 620, 47–60.

- Zou, Y.; Cheng, A.H.; Aldossary, A.; Bai, J.; Leong, S.X.; Campos-Gonzalez-Angulo, J.A.; Choi, C.; Ser, C.T.; Tom, G.; Wang, A.; et al. El Agente: An Autonomous Agent for Quantum Chemistry, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2505.02484].

- Lu, C.; Lu, C.; Lange, R.T.; Foerster, J.; Clune, J.; Ha, D. The AI Scientist: Towards Fully Automated Open-Ended Scientific Discovery, 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2408.06292].

- Gottweis, J.; Weng, W.H.; Daryin, A.; Tu, T.; Palepu, A.; Sirkovic, P.; Myaskovsky, A.; Weissenberger, F.; Rong, K.; Tanno, R.; et al. Towards an AI co-scientist, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2502.18864].

- Sarkar, M.; Bolliet, B.; Dimitrov, A.; Laverick, A.; Villaescusa-Navarro, F.; Xu, L.; Íñigo Zubeldia. Multi-Agent System for Cosmological Parameter Analysis. arXiv preprint 2024, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2412.00431].

- Lu, S.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, T.J.; Kos, P.; Cirac, J.I.; Schölkopf, B. Can Theoretical Physics Research Benefit from Language Agents?, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2506.06214].

- Jin, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Cong, L. STELLA: Self-Evolving LLM Agent for Biomedical Research. arXiv preprint 2025, [2507.02004].

- Gao, S.; Fang, A.; Lu, Y.; Fuxin, L.; Shao, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zou, C.; Schneider, J.; Chen, L.; Liu, C.; et al. Empowering biomedical discovery with AI agents. Cell 2024, 187, 6125–6151. [CrossRef]

- Boiko, D.A.; MacKnight, R.; Kline, B.; Gomes, G. Autonomous chemical research with large language models. Nature 2023, 624, 570–578. [CrossRef]

- Bran, A.M.; Cox, S.; Schilter, O.; Baldassari, C.; White, A.D.; Schwaller, P. Augmenting large language models with chemistry tools. Nature Machine Intelligence 2024, 6, 525–535. Published 08 May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Acharya, S.; Simko, S.; Bhardwaj, D.; Haghighat, A.; Sachan, M.; Janzing, D.; Schölkopf, B.; Jin, Z. Causal AI Scientist: Facilitating Causal Data Science with Large Language Models. Manuscript Under Review 2025.

- Haase, J.; Pokutta, S. Beyond Static Responses: Multi-Agent LLM Systems as a New Paradigm for Social Science Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.01839.

- Parkes, D.C.; Wellman, M.P. Economic reasoning and artificial intelligence. Science 2015, 349, 267 – 272.

- Chen, X.; Yi, H.; You, M.; Liu, W.Z.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y. Enhancing diagnostic capability with multi-agents conversational large language models. NPJ Digital Medicine 2025, 8, 65. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.X.; Hong, S. ArgMed-Agents: Explainable Clinical Decision Reasoning with LLM Disscusion via Argumentation Schemes. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM) 2024, pp. 5486–5493.

- xAI. Introducing Grok-4. https://x.ai/news/grok-4, 2025.

- DeepMind. Advanced version of Gemini with Deep Think officially achieves gold-medal standard at the International Mathematical Olympiad, 2025. DeepMind Blog Post.

- Ghafarollahi, A.; Buehler, M.J. SciAgents: Automating scientific discovery through multi-agent intelligent graph reasoning. arXiv preprint 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2409.05556].

- Ghareeb, A.E.; Chang, B.; Mitchener, L.; Yiu, A.; Warner, C.; Riley, P.; Krstic, G.; Yosinski, J. Robin: A Multi-Agent System for Automating Scientific Discovery. arXiv preprint 2025, [2505.13400].

- Phan, L.; Gatti, A.; Han, Z.; Li, N.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.B.C.; Shaaban, M.; Ling, J.; Shi, S.; et al. Humanity’s Last Exam, 2025, [arXiv:cs.LG/2501.14249].

- Luo, Z.; Yang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Yang, W.; Du, X. LLM4SR: A Survey on Large Language Models for Scientific Research. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.04306 2025.

- Zheng, T.; Deng, Z.; Tsang, H.T.; Wang, W.; Bai, J.; Wang, Z.; Song, Y. From Automation to Autonomy: A Survey on Large Language Models in Scientific Discovery. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.13259 2025.

- Zhuang, Z.; Chen, J.; Xu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, J. Large language models for automated scholarly paper review: A survey. Information Fusion 2025, 124, 103332. [CrossRef]

- Borghoff, U.M.; Bottoni, P.; Pareschi, R. An Organizational Theory for Multi-Agent Interactions Integrating Human Agents, LLMs, and Specialized AI. Discover Computing 2025.

- Yan, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Miao, D.; Li, C. Beyond Self-Talk: A Communication-Centric Survey of LLM-Based Multi-Agent Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2502.14321.

- Khalili, M.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y. Multi-Agent Systems for Model-based Fault Diagnosis. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 1211–1216. [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Li, X. PeerGuard: Defending Multi-Agent Systems Against Backdoor Attacks Through Mutual Reasoning. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.11642.

- Chen, H.; Xiong, M.; Lu, Y.; Han, W.; Deng, A.; He, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hooi, B. MLR-Bench: Evaluating AI Agents on Open-Ended Machine Learning Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.19955.

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xie, T.; Ni, J.; Gao, B.; Li, Y.; Tang, S.; Ouyang, W.; Cambria, E.; Zhou, D. ResearchBench: Benchmarking LLMs in Scientific Discovery via Inspiration-Based Task Decomposition. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.21248.

- Kon, P.T.J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, X.; Ding, Q.; Peng, J.; Xing, J.; Huang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Srinivasa, J.; Lee, M.; et al. EXP-Bench: Can AI Conduct AI Research Experiments? ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.24785.

- Siegel, Z.S.; Kapoor, S.; Nagdir, N.; Stroebl, B.; Narayanan, A. CORE-Bench: Fostering the Credibility of Published Research Through a Computational Reproducibility Agent Benchmark. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. 2024, 2024.

- Son, G.; Hong, J.; Fan, H.; Nam, H.; Ko, H.; Lim, S.; Song, J.; Choi, J.; Paulo, G.; Yu, Y.; et al. When AI Co-Scientists Fail: SPOT-a Benchmark for Automated Verification of Scientific Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.11855.

- L’ala, J.; O’Donoghue, O.; Shtedritski, A.; Cox, S.; Rodriques, S.G.; White, A.D. PaperQA: Retrieval-Augmented Generative Agent for Scientific Research. ArXiv 2023, abs/2312.07559.

- Starace, G.; Jaffe, O.; Sherburn, D.; Aung, J.; Chan, J.S.; Maksin, L.; Dias, R.; Mays, E.; Kinsella, B.; Thompson, W.; et al. PaperBench: Evaluating AI’s Ability to Replicate AI Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.01848.

- Li, G.; Hammoud, H.; Itani, H.; Khizbullin, D.; Ghanem, B. CAMEL: Communicative Agents for "Mind" Exploration of Large Language Model Society. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023.

- Zheng, C.; Cao, Y.; Dong, X.; He, T. Demonstrations of Integrity Attacks in Multi-Agent Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.04572.

- Amayuelas, A.; Yang, X.; Antoniades, A.; Hua, W.; Pan, L.; Wang, W. MultiAgent Collaboration Attack: Investigating Adversarial Attacks in Large Language Model Collaborations via Debate. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2024.

- Jin, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhu, K.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, J. AgentReview: Exploring Peer Review Dynamics with LLM Agents. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2024, Miami, FL, USA, November 12-16, 2024; Al-Onaizan, Y.; Bansal, M.; Chen, Y., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 1208–1226. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Weng, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y. DeepReview: Improving LLM-based Paper Review with Human-like Deep Thinking Process. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.08569.

- Yu, W.; Tang, S.; Huang, Y.; Dong, N.; Fan, L.; Qi, H.; Guo, C. Dynamic Knowledge Exchange and Dual-Diversity Review: Concisely Unleashing the Potential of a Multi-Agent Research Team. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.18348 2025.

- Weng, Y.; Zhu, M.; Bao, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L. CycleResearcher: Improving Automated Research via Automated Review. ArXiv 2024, abs/2411.00816.

- Du, Y.; Li, S.; Torralba, A.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Mordatch, I. Improving Factuality and Reasoning in Language Models through Multiagent Debate. In Proceedings of the Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2024, Vienna, Austria, July 21-27, 2024, 2024.

- Seo, M.; Baek, J.; Lee, S.; Hwang, S.J. Paper2Code: Automating Code Generation from Scientific Papers in Machine Learning. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.17192.

- Yang, Y.; Yi, E.; Ko, J.; Lee, K.; Jin, Z.; Yun, S. Revisiting Multi-Agent Debate as Test-Time Scaling: A Systematic Study of Conditional Effectiveness. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.22960.

- Perera, R.; Basnayake, A.; Wickramasinghe, M. Auto-scaling LLM-based multi-agent systems through dynamic integration of agents. Frontiers in AI 2025.

- Tang, X.; Qin, T.; Peng, T.; Zhou, Z.; Shao, D.; Du, T.; Wei, X.; Xia, P.; Wu, F.; Zhu, H.; et al. Agent KB: Leveraging Cross-Domain Experience for Agentic Problem Solving, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2507.06229].

- Surabhi, P.S.M.; Mudireddy, D.R.; Tao, J. ThinkTank: A Framework for Generalizing Domain-Specific AI Agent Systems into Universal Collaborative Intelligence Platforms. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.02931.

- Ifargan, T.; Hafner, L.; Kern, M.; Alcalay, O.; Kishony, R. Autonomous LLM-driven research from data to human-verifiable research papers. ArXiv 2024, abs/2404.17605.

- Schmidgall, S.; Moor, M. AgentRxiv: Towards Collaborative Autonomous Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.18102.

- Zhang, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Z.; An, D. OriGene: A Self-Evolving Virtual Disease Biologist Automating Therapeutic Target Discovery. bioRxiv 2025.

- Mukherjee, A.; Kumar, P.; Yang, B.; Chandran, N.; Gupta, D. Privacy Preserving Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning in Supply Chains. ArXiv 2023, abs/2312.05686.

- Shanmugarasa, Y.; Ding, M.; Chamikara, M.; Rakotoarivelo, T. SoK: The Privacy Paradox of Large Language Models: Advancements, Privacy Risks, and Mitigation. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.12699.

- Li, Y.; Choi, D.; Chung, J.; Kushman, N.; Schrittwieser, J.; Leblond, R.; Eccles, T.; Keeling, J.; Gimeno, F.; Dal Lago, A.; et al. Competition-level code generation with AlphaCode. Science 2022, 378, 1092–1097.

- Pan, R.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C. CodeCoR: An LLM-Based Self-Reflective Multi-Agent Framework for Code Generation. ArXiv 2025, abs/2501.07811.

- Lin, Z.; Shen, Y.; Cai, Q.; Sun, H.; Zhou, J.; Xiao, M. AutoP2C: An LLM-Based Agent Framework for Code Repository Generation from Multimodal Content in Academic Papers. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.20115.

- Dobbins, N.J.; Xiong, C.; Lan, K.; Yetisgen-Yildiz, M. Large Language Model-Based Agents for Automated Research Reproducibility: An Exploratory Study in Alzheimer’s Disease. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.23852.

- Ju, T.; Wang, B.; Fei, H.; Lee, M.L.; Hsu, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, P.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Investigating the Adaptive Robustness with Knowledge Conflicts in LLM-based Multi-Agent Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2502.15153.

- Azadeh, R. Advances in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning: Persistent Autonomy and Robot Learning Lab Report 2024. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.21088 2024.

- Swanson, K.; Wu, W.; Bulaong, N.L.; Pak, J.E.; Zou, J. The Virtual Lab: AI Agents Design New SARS-CoV-2 Nanobodies with Experimental Validation. bioRxiv 2024. Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, C.; Xia, Y.; Shi, R.; Dang, Y.; Xie, Z.; You, Z.; Chen, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, W.; et al. Cross-Task Experiential Learning on LLM-based Multi-Agent Collaboration. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.23187.

- Szymanski, N.; Rendy, B.; Fei, Y.; Kumar, R.E.; He, T.; Milsted, D.; McDermott, M.J.; Gallant, M.C.; Cubuk, E.D.; Merchant, A.; et al. An autonomous laboratory for the accelerated synthesis of novel materials. Nature 2023, 624, 86 – 91.

- Jin, Z.; Wu, Q.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Xu, W.; Liao, Y.; Feng, L.; Hu, M.; Li, B. TopoMAS: Large Language Model Driven Topological Materials Multiagent System. arXiv preprint 2025, [2507.04053].

- Wölflein, G.; Ferber, D.; Truhn, D.; Arandjelovi’c, O.; Kather, J. LLM Agents Making Agent Tools. ArXiv 2025, abs/2502.11705.

- Seo, S.; Kim, J.; Shin, M.; Suh, B. LLMDR: LLM-Driven Deadlock Detection and Resolution in Multi-Agent Pathfinding. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.00717.

- de Witt, C.S. Open Challenges in Multi-Agent Security: Towards Secure Systems of Interacting AI Agents. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.02077.

- Sun, L.; Yang, Y.; Duan, Q.; Shi, Y.; Lyu, C.; Chang, Y.C.; Lin, C.T.; Shen, Y. Multi-Agent Coordination across Diverse Applications: A Survey, 2025, [arXiv:cs.MA/2502.14743].

- Kusne, A.G.; McDannald, A. Scalable multi-agent lab framework for lab optimization. Matter 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Sarkar, M.; Lonappan, A.I.; Íñigo Zubeldia.; Villanueva-Domingo, P.; Casas, S.; Fidler, C.; Amancharla, C.; Tiwari, U.; Bayer, A.; et al. Open Source Planning & Control System with Language Agents for Autonomous Scientific Discovery. arXiv preprint 2025, [2507.07257].

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Zheng, T.; Song, M. Parallelized Planning-Acting for Efficient LLM-based Multi-Agent Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.03505.

- Park, C.; Han, S.; Guo, X.; Ozdaglar, A.; Zhang, K.; Kim, J.K. MAPoRL: Multi-Agent Post-Co-Training for Collaborative Large Language Models with Reinforcement Learning. ArXiv 2025, abs/2502.18439.

- Lan, T.; Zhang, W.; Lyu, C.; Li, S.; Xu, C.; Huang, H.; Lin, D.; Mao, X.L.; Chen, K. Training Language Models to Critique With Multi-agent Feedback. ArXiv 2024, abs/2410.15287.

- Du, Z.; Qian, C.; Liu, W.; Xie, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, R.; Dang, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, C.; Tian, Y.; et al. Multi-Agent Collaboration via Cross-Team Orchestration. arXiv 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2406.08979]. Accepted to Findings of ACL 2025.

- Zhu, K.; Du, H.; Hong, Z.; Yang, X.; Guo, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qian, C.; Tang, X.; Ji, H.; et al. MultiAgentBench: Evaluating the Collaboration and Competition of LLM agents. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.01935.

- Soldatova, L.N.; Rzhetsky, A. Representation of research hypotheses. Journal of Biomedical Semantics 2011, 2, S9 – S9.

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, K.; Fang, M. Deep Research Agents: A Systematic Examination And Roadmap. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.18096 2025.

- Tran, K.T.; Dao, D.; Nguyen, M.D.; Pham, Q.V.; O’Sullivan, B.; Nguyen, H.D. Multi-Agent Collaboration Mechanisms: A Survey of LLMs. ArXiv 2025, abs/2501.06322.

- Bandi, C.; Harrasse, A. Adversarial Multi-Agent Evaluation of Large Language Models through Iterative Debates. ArXiv 2024, abs/2410.04663.

- Pu, Z.; Ma, H.; Hu, T.; Chen, M.; Liu, B.; Liang, Y.; Ai, X. Coevolving with the Other You: Fine-Tuning LLM with Sequential Cooperative Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. ArXiv 2024, abs/2410.06101.

- Chun, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Ahmed, I. Is Multi-Agent Debate (MAD) the Silver Bullet? An Empirical Analysis of MAD in Code Summarization and Translation. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.12029.

- Pu, Y.; Lin, T.; Chen, H. PiFlow: Principle-aware Scientific Discovery with Multi-Agent Collaboration. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.15047.

- Song, K.; Trotter, A.; Chen, J.Y. LLM Agent Swarm for Hypothesis-Driven Drug Discovery. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.17967.

- Koscher, B.A.; Canty, R.B.; McDonald, M.A.; Greenman, K.P.; McGill, C.J.; Bilodeau, C.L.; Jin, W.; Wu, H.; Vermeire, F.H.; Jin, B.; et al. Autonomous, multiproperty-driven molecular discovery: From predictions to measurements and back. Science 2023, 382.

- Chen, X.; Che, M.; et al. An automated construction method of 3D knowledge graph based on multi-agent systems in virtual geographic scene. International Journal of Digital Earth 2024, 17, 2449185. [CrossRef]

- Al-Neaimi, A.; Qatawneh, S.; Saiyd, N.A. Conducting Verification And Validation Of Multi- Agent Systems, 2012, [arXiv:cs.SE/1210.3640].

- Nguyen, T.P.; Razniewski, S.; Weikum, G. Towards Robust Fact-Checking: A Multi-Agent System with Advanced Evidence Retrieval. arXiv preprint 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2506.17878].

- Ferrag, M.A.; Tihanyi, N.; Hamouda, D.; Maglaras, L. From Prompt Injections to Protocol Exploits: Threats in LLM-Powered AI Agents Workflows. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.23260 2025.

- Wang, H.; Du, X.; Yu, W.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, K.; Chu, Z.; Yan, L.; Guan, Y. Learning to break: Knowledge-enhanced reasoning in multi-agent debate system. Neurocomputing 2023, 618, 129063.

- Li, Z.; Chang, Y.; Le, X. Simulating Expert Discussions with Multi-agent for Enhanced Scientific Problem Solving. Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Scholarly Document Processing (SDP 2024) 2024.

- Pantiukhin, D.; Shapkin, B.; Kuznetsov, I.; Jost, A.A.; Koldunov, N. Accelerating Earth Science Discovery via Multi-Agent LLM Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.05854.

- Solovev, G.V.; Zhidkovskaya, A.B.; Orlova, A.; Vepreva, A.; Tonkii, I.; Golovinskii, R.; Gubina, N.; Chistiakov, D.; Aliev, T.A.; Poddiakov, I.; et al. Towards LLM-Driven Multi-Agent Pipeline for Drug Discovery: Neurodegenerative Diseases Case Study. In Proceedings of the OpenReview Preprint, 2024.

- Sami, M.A.; Rasheed, Z.; Kemell, K.; Waseem, M.; Kilamo, T.; Saari, M.; Nguyen-Duc, A.; Systä, K.; Abrahamsson, P. System for systematic literature review using multiple AI agents: Concept and an empirical evaluation. CoRR 2024, abs/2403.08399, [2403.08399]. [CrossRef]

- Mankowitz, D.J.; Michi, A.; Zhernov, A.; Gelada, M.; Selvi, M.; Paduraru, C.; Leurent, E.; Iqbal, S.; Lespiau, J.B.; Ahern, A.; et al. Faster sorting algorithms discovered using deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2023, 618, 257–263.

- Trinh, T.H.; Wu, Y.; Le, Q.V.; He, H.; Luong, T. Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations. Nature 2024, 625, 476–482.

- Fawzi, A.; Balog, M.; Huang, A.; Hubert, T.; Romera-Paredes, B.; Barekatain, M.; Novikov, A.; Ruiz, F.J.; Schrittwieser, J.; Swirszcz, G.; et al. Discovering faster matrix multiplication algorithms with reinforcement learning. Nature 2022, 610, 47–53.

- Vinyals, O.; Babuschkin, I.; Czarnecki, W.M.; Mathieu, M.; Dudzik, A.; Chung, J.; Choi, D.H.; Powell, R.; Ewalds, T.; Georgiev, P.; et al. Grandmaster level in StarCraft II using multi-agent reinforcement learning. Nature 2019, 575, 350–354.

- Silver, D.; Schrittwieser, J.; Simonyan, K.; Antonoglou, I.; Huang, A.; Guez, A.; Hubert, T.; Baker, L.; Lai, M.; Bolton, A.; et al. Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge. Nature 2017, 550, 354–359. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Gordon, C.; Mert, U.; Sell, M. MASS: A Parallelizing Library for Multi-Agent Spatial Simulation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSIM Conference on Principles of Advanced Discrete Simulation (PADS). ACM, 2013, pp. 161–170. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, W.; Ding, J.; Liu, J. Agent-Oriented Planning in Multi-Agent Systems. arXiv preprint 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2410.02189].

- Xiang, Y.; Yan, H.; Ouyang, S.; Gui, L.; He, Y. SciReplicate-Bench: Benchmarking LLMs in Agent-driven Algorithmic Reproduction from Research Papers. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.00255.

- Tang, K.; Wu, A.; Lu, Y.; Sun, G. Collaborative Editable Model. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.14146.

- Chen, N.; HuiKai, A.L.; Wu, J.; Hou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; He, B. XtraGPT: LLMs for Human-AI Collaboration on Controllable Academic Paper Revision. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.11336.

| 1 | John Bardeen was the only person to have received the Nobel Prize in Physics twice, for inventing the transistors and the theory of superconductivity. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1972/bardeen/speech

|

| 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).