Introduction

Scientific discovery represents a unique mechanism through which intelligent systems can recursively enhance their own capabilities [

1,

2,

3]. Each discovery becomes a tool for making further discoveries, each breakthrough expands the horizon of the possible [

4,

5]. Yet current AI scientist systems remain confined to predefined domains and fixed architectures, accelerating research within existing paradigms but unable to create new fields of knowledge or spawn novel types of investigators for unprecedented challenges [

6].

Recent breakthroughs in AI-assisted scientific research demonstrate significant progress. The AI Co-Scientist [

7] employs multi-agent architectures generating novel biomedical hypotheses through tournament-based evolution. The AI Scientist-v2 [

8] autonomously produces complete research papers that pass peer review in machine learning, building on foundations laid by the original AI Scientist [

4]. These systems already show emergent capabilities: self-improvement through feedback loops [

9,

10], autonomous experimental design [

11], and cross-domain pattern recognition [

12]. Other notable systems include ResearchAgent [

13], which leverages encyclopedic knowledge for iterative idea generation, Agent Laboratory [

14], which completes the entire research process from literature review to report writing, and NovelSeek [

15], which provides hypothesis-to-verification workflows.

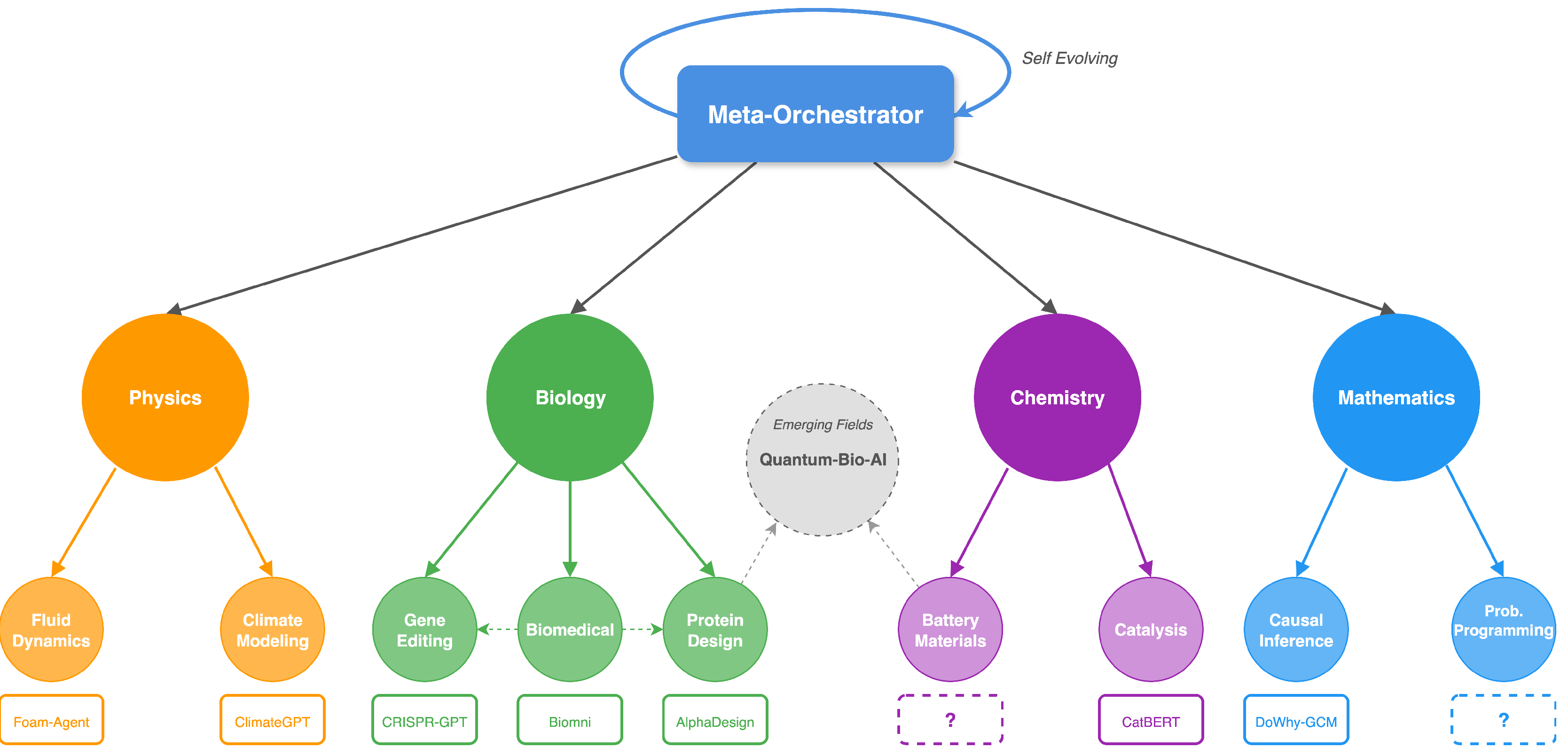

Figure 1.

Self-evolving hierarchical multi-agent system demonstrating autonomous scientific discovery. Meta-orchestrators coordinate domain specialists that dynamically spawn task-specific AI scientists, while the system autonomously recognizes the need for new research areas (Quantum-Bio-AI emergence) and forms interdisciplinary connections (dotted lines). This architecture transcends static multi-agent systems by evolving its own structure as it encounters novel scientific challenges.

Figure 1.

Self-evolving hierarchical multi-agent system demonstrating autonomous scientific discovery. Meta-orchestrators coordinate domain specialists that dynamically spawn task-specific AI scientists, while the system autonomously recognizes the need for new research areas (Quantum-Bio-AI emergence) and forms interdisciplinary connections (dotted lines). This architecture transcends static multi-agent systems by evolving its own structure as it encounters novel scientific challenges.

However, these systems share fundamental architectural limitations that prevent truly autonomous discovery [

16,

17]. They operate at a single level of abstraction within predefined territories. The AI Scientist generates papers but remains confined to predetermined research templates. ResearchAgent cannot modify its own investigative approach when encountering novel phenomena. Even sophisticated multi-agent systems like AutoGen [

18] and CAMEL [

19] maintain static role assignments and cannot spawn new agent types when facing unprecedented challenges. The fundamental limitation is architectural rigidity: these systems excel within their designed domains but cannot recognize when a problem requires not just different parameters but entirely different cognitive architectures [

20,

21].

Recent work on automated agent design offers partial solutions but falls short of enabling true architectural evolution. AFlow [

22] optimizes workflows through code representation, achieving efficiency gains but within predetermined design spaces. ADAS [

23] uses meta-agents to program new agents, yet these remain variations on existing templates rather than fundamentally new architectures. Darwin [

24] demonstrates self-improvement through code modification but focuses on optimizing existing capabilities rather than creating new ones. These approaches lack the meta-cognitive capability to assess their own limitations and create specialized agents with genuinely novel architectures [

25,

26].

We present a framework for self-evolving AI scientists organized in hierarchical multi-agent architectures that continuously enhance their capabilities through the discoveries they make [

16,

24,

27]. Unlike existing systems that operate as sophisticated tools within human-defined boundaries, our proposed architecture can recognize when entirely new investigative approaches are needed and create the specialized agents to pursue them [

23,

24,

28].

What distinguishes our approach is the introduction of hierarchical self-evolution: systems that not only optimize within their current structure but recognize when that structure itself must change [

29,

30]. This requires moving beyond task-level automation to system-level adaptation, where the discovery process itself drives architectural evolution. Through dynamic reorganization, protocol-based interoperability, and most critically, the ability to generate entirely new agent types, these systems can evolve their own architectures and generate new cognitive tools as they encounter the unknown [

31,

32]. This paper presents the first comprehensive framework for such systems, establishing a new paradigm where AI scientists enhance their discovery capabilities through the knowledge they create.

Hierarchical Self-Evolving Architecture

Our proposed architecture operates through dynamic hierarchies that evolve with discovery needs [

21,

33]. Unlike static multi-agent systems or monolithic models, this approach enables emergent specialization while maintaining computational efficiency.

The system organizes as a tree structure with three primary levels. Meta-orchestrators at the apex coordinate research programs across multiple domains, identifying patterns and opportunities for cross-disciplinary investigation. Domain specialists manage focused research areas, spawning task-specific AI scientists as needed. These task-specific agents conduct detailed investigations, from hypothesis generation to experimental validation [

11,

34].

Critical to this architecture is dynamic reorganization. When frequently collaborating agents identify stable interaction patterns, they may merge into unified teams. When orchestrators become overloaded, they spawn sub-hierarchies to distribute cognitive load. When entirely new research territories emerge, the system creates new branches with specialized agents designed for those domains [

30,

35].

This hierarchical organization provides quantifiable advantages. Consider a system with

n agents organized in a tree of branching factor

b and depth

d. Message passing complexity reduces from

for fully connected systems to

for hierarchical organization. This efficiency becomes critical as systems scale to thousands of specialized agents [

36,

37].

The spawning process (Algorithm 1) enables the system to recognize capability gaps and create appropriate agents. When confronting a novel challenge, the system analyzes whether existing agents can address it through recombination or whether fundamentally new architectures are required. This decision drives the generation of specialized agents with tailored cognitive capabilities.

|

Algorithm 1:Dynamic Agent Spawning |

-

Require:

task_requirements, current_hierarchy, resource_constraints -

Ensure:

updated_hierarchy - 1:

capability_gap ← AnalyzeCapabilityMismatch(task_requirements, current_hierarchy) - 2:

if capability_gap.requires_new_agent then

- 3:

agent_spec ← DesignAgentArchitecture(capability_gap) - 4:

new_agent ← SpawnAgent(agent_spec, MCP_protocol) - 5:

optimal_position ← DetermineHierarchicalPosition(new_agent, current_hierarchy) - 6:

updated_hierarchy ← InsertAgent(new_agent, optimal_position) - 7:

EstablishCommunicationChannels(new_agent, updated_hierarchy) - 8:

end if - 9:

return updated_hierarchy |

Task decomposition (Algorithm 2) illustrates how the hierarchy enables efficient problem solving. Orchestrators maintain high-level understanding while delegating specialized work, creating new specialists when existing capabilities prove insufficient. This approach balances depth of expertise with breadth of integration.

Protocol-Based Interoperability

Effective collaboration in our hierarchical system requires standardized communication protocols that enable seamless interaction while preserving agent autonomy [

38,

39]. We adopt the Model Context Protocol (MCP) as a foundation, extending it to support dynamic agent generation and hierarchical coordination.

MCP operates through JSON-RPC style communication, enabling language-agnostic interaction between agents while maintaining type safety and versioning compatibility. MCP provides several critical capabilities for our architecture. First, it enables agents to expose their capabilities through standardized interfaces, allowing orchestrators to discover and utilize specialized functions without hard-coded dependencies. Second, it supports context passing across hierarchical levels, ensuring that high-level research goals inform low-level investigations while detailed findings propagate upward. Third, it facilitates peer-to-peer collaboration when agents identify opportunities for direct interaction outside the hierarchy [

40,

41].

|

Algorithm 2:Hierarchical Task Decomposition |

-

Require:

scientific_problem, orchestrator_agent -

Ensure:

solution - 1:

subtasks ← orchestrator_agent.DecomposeTask(scientific_problem) - 2:

for all subtask ∈ subtasks do

- 3:

if orchestrator_agent.CanHandleDirectly(subtask) then

- 4:

partial_solution ← orchestrator_agent.Solve(subtask) - 5:

else

- 6:

specialist ← FindOrSpawnSpecialist(subtask) - 7:

partial_solution ← specialist.Solve(subtask) - 8:

end if

- 9:

solutions.Append(partial_solution) - 10:

end for - 11:

solution ← orchestrator_agent.IntegrateSolutions(solutions) - 12:

return solution |

The protocol must evolve with the system. As new agent types emerge with unique capabilities, they negotiate extensions to the base protocol while maintaining backward compatibility. This creates a living ecosystem of communication that grows more sophisticated with each discovery, rather than a fixed message-passing system that constrains future development.

Importantly, MCP enables resource negotiation across the hierarchy. Agents can request computational resources, access to instruments, or collaboration with peers based on research needs. Meta-orchestrators allocate these resources dynamically, prioritizing promising research directions while ensuring system stability [

42,

43].

Three Implementation Pathways

Building a comprehensive ecosystem of interoperable AI scientists requires multiple complementary approaches [

1,

44]. We identify three pathways that together enable both immediate capability and long-term evolution.

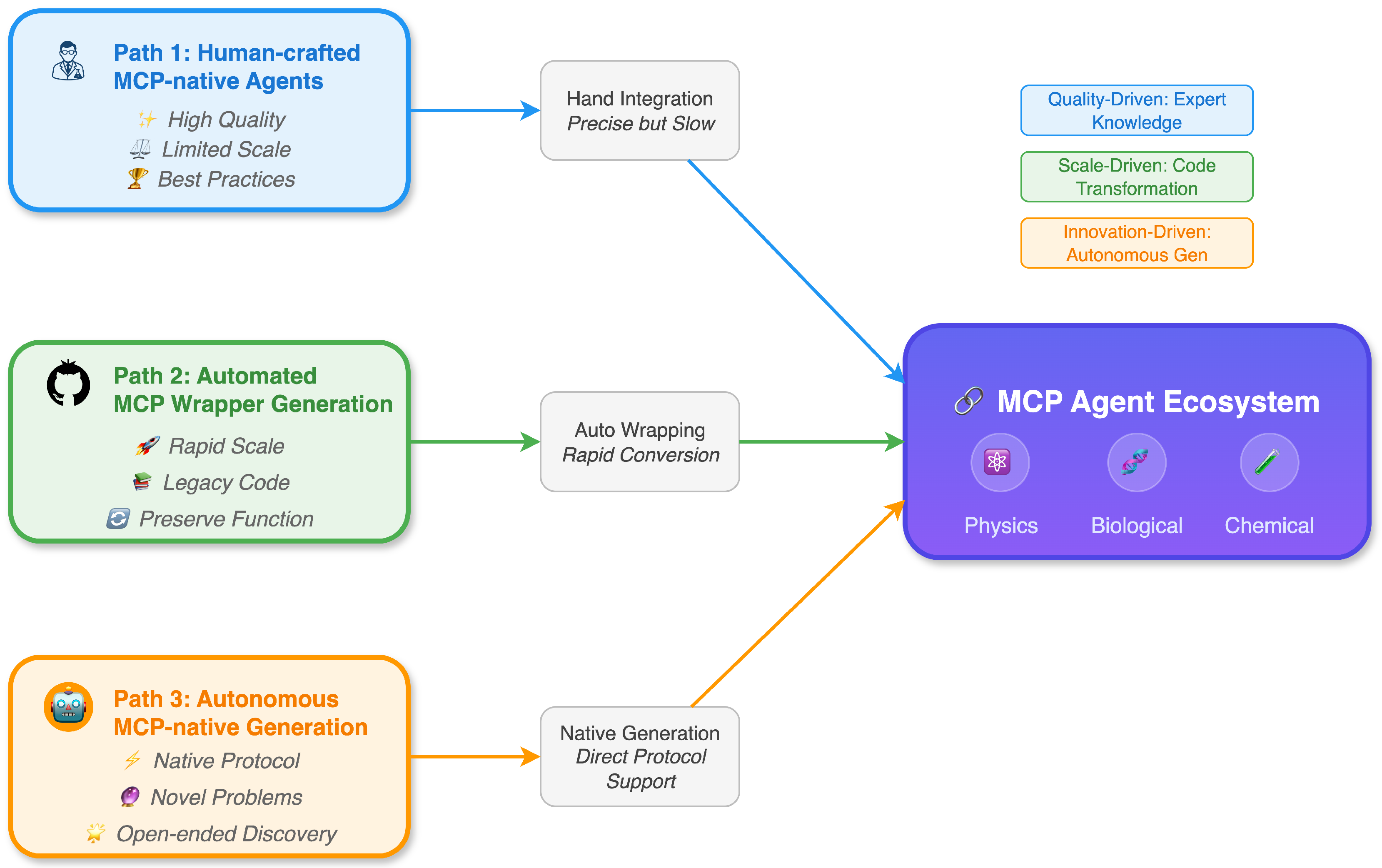

Figure 2 illustrates how these three pathways converge to create a unified ecosystem of MCP-enabled agents.

Path 1: Human-crafted protocol-native agents leverages domain expertise to create high-quality specialized agents [

29,

45,

46,

47]. Scientists encode decades of knowledge into agents that natively support MCP, establishing benchmarks for quality and demonstrating best practices. While limited in scale due to manual effort, these agents provide critical capabilities in complex domains like computational fluid dynamics [

48] and molecular dynamics [

29]. They serve as exemplars for automated generation and ensure that crucial domain knowledge is preserved in the ecosystem.

Path 2: Automated transformation of existing codebases addresses the vast repository of scientific software that remains isolated due to incompatible interfaces [

49,

50]. Large language models can analyze legacy code and generate MCP wrappers that preserve functionality while adding standardized communication. This approach rapidly populates the ecosystem with thousands of specialized tools, from physics simulators [

51,

52] to data analysis pipelines [

53,

54]. The key innovation lies in maintaining scientific accuracy while enabling interoperability.

Path 3: Autonomous generation of novel agents represents the most transformative approach [

23,

55]. Systems analyze emerging research needs and synthesize entirely new agent architectures with built-in protocol support. Unlike retrofitting existing code, this pathway creates agents from first principles, designing both cognitive capabilities and communication interfaces simultaneously. This enables creation of agents for problems nobody anticipated, with architectures optimized for specific discovery tasks [

56].

Figure 2.

Three pathways to MCP agent ecosystem development. Human-crafted agents (Path 1) provide quality foundations, automated wrapper generation (Path 2) enables rapid scaling from legacy code, and autonomous generation (Path 3) creates novel agents for unprecedented problems. All paths converge into a unified scientific discovery ecosystem with standardized protocol communication across diverse domains.

Figure 2.

Three pathways to MCP agent ecosystem development. Human-crafted agents (Path 1) provide quality foundations, automated wrapper generation (Path 2) enables rapid scaling from legacy code, and autonomous generation (Path 3) creates novel agents for unprecedented problems. All paths converge into a unified scientific discovery ecosystem with standardized protocol communication across diverse domains.

The critical insight is that while human-crafted agents provide quality and automated transformation provides scale, only autonomous generation enables the system to transcend its initial limitations [

24,

57]. The first two paths bootstrap the ecosystem, but the third enables true architectural evolution in response to discovery needs.

Table 1.

Comparison of three implementation pathways

Table 1.

Comparison of three implementation pathways

| |

Path 1 |

Path 2 |

Path 3 |

| |

Human-crafted |

Automated transformation |

Autonomous generation |

| Quality |

High |

Medium |

Variable |

| Scalability |

Low |

High |

High |

| Novel capabilities |

Limited |

No |

Yes |

| Development effort |

High |

Medium |

Low (once developed) |

Case Study: Adaptive Materials Discovery

To illustrate how our hierarchical system operates in practice, consider a materials discovery scenario that begins with a focused investigation but evolves to require interdisciplinary collaboration.

Initially, a materials science orchestrator receives a request to develop high-temperature superconductors for quantum computing applications. The orchestrator spawns specialized agents for crystal structure prediction, electronic property calculation, and synthesis pathway planning. These agents work within established materials science frameworks, sharing results through MCP.

During investigation, the electronic property agent discovers unexpected quantum coherence effects that persist at higher temperatures than theory predicts. Recognizing this anomaly exceeds its domain knowledge, it signals the orchestrator, which analyzes the capability gap. The system determines that understanding this phenomenon requires expertise in quantum biology—specifically, how certain proteins maintain quantum coherence in warm environments [

58,

59].

The meta-orchestrator recognizes no existing agent combines materials science with quantum biology expertise. Following Algorithm 1, it generates specifications for a new hybrid agent type, incorporating protein structure analysis capabilities with solid-state physics models. This new agent identifies structural motifs in proteins that could inspire novel superconductor designs.

As research progresses, the system’s hierarchy reorganizes. The frequently collaborating materials and bio-quantum agents form a dedicated sub-hierarchy for bio-inspired quantum materials. New specialist agents emerge for specific tasks: one for analyzing electron-phonon coupling in organic frameworks, another for designing synthesis pathways that preserve quantum properties [

60,

61].

This case demonstrates key architectural features: recognition of capability gaps, autonomous generation of appropriate agent types, and dynamic reorganization based on discovery patterns. The system not only solves the immediate problem but evolves new capabilities that enhance future discovery potential.

Discussion and Future Directions

The framework presented here establishes a new paradigm for AI-assisted scientific discovery, moving beyond acceleration within fixed domains toward systems that evolve their own architectures in response to discovery needs [

6,

27].

Near-term development should focus on creating the foundational ecosystem. Establishing robust MCP implementations across key scientific domains will enable early demonstrations of hierarchical coordination. Developing tools for automated code transformation will rapidly expand the agent library. Most critically, advancing autonomous agent generation techniques will determine whether these systems remain sophisticated orchestrators or become genuine pioneers of knowledge.

The quality of autonomous architecture generation remains the central technical challenge. Current approaches like ADAS [

23] and Darwin [

24] achieve success in narrow domains but struggle with scientific complexity. We propose a staged development approach: beginning with template-based generation where new agents combine existing components, progressing to guided generation with human-provided constraints, and ultimately achieving free-form generation for truly novel architectures. This progression allows the field to build expertise and validation methods incrementally while working toward full autonomy.

Several critical challenges require continued research. When AI systems propose theories or designs beyond human understanding, how do we verify their validity [

62,

63]? As systems dynamically reorganize, how do we maintain coherence and prevent degradation [

25,

64]? How should resources be allocated across competing research directions when AI systems identify opportunities humans don’t yet comprehend [

42,

43]? These questions are not barriers but define the research agenda for the coming years.

The implications extend beyond individual discoveries. As hierarchical AI scientists identify connections across disciplines faster than traditional institutional structures can adapt, they may catalyze new forms of scientific organization [

3,

65]. Research programs could dynamically form around emerging phenomena rather than historical departmental boundaries.

The path forward requires collaboration across AI research, domain sciences, and science policy [

31,

66]. By building systems that enhance their own capabilities through discovery, we create a positive feedback loop where each breakthrough enables more sophisticated investigation. This recursive improvement through scientific discovery offers a concrete path toward AI systems that continuously expand the frontiers of knowledge.

Key open questions merit investigation: How can we ensure that autonomously generated agents maintain scientific rigor while exploring beyond established frameworks? What governance mechanisms can guide these systems while preserving their ability to pursue unexpected directions? How do we preserve meaningful human participation as AI systems become increasingly autonomous in their scientific pursuits?

The vision we present is ambitious but grounded in current technological capabilities and clear development pathways. Through hierarchical organization, protocol-based interoperability, and autonomous agent generation, we can build AI scientists that don’t just accelerate research but fundamentally transform how scientific discovery occurs. The question is not whether such systems are possible, but how quickly we can realize their potential while ensuring they remain beneficial tools for human knowledge and progress.

References

- Ren, S.; Jian, P.; Ren, Z.; Leng, C.; Xie, C.; Zhang, J. Towards Scientific Intelligence: A Survey of LLM-based Scientific Agents, 2025. arXiv:2503.24047. [CrossRef]

- Gridach, M.; Nanavati, J.; Abidine, K.Z.E.; Mendes, L.; Mack, C. Agentic AI for Scientific Discovery: A Survey of Progress, Challenges, and Future Directions, 2025. arXiv:2503.08979. [CrossRef]

- Koutra, D.; Huang, L.; Kulkarni, A.; Prioleau, T.; Soh, B.; Yan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zou, J. TOWARDS AGENTIC AI FOR SCIENCE: HYPOTHESIS GENERATION, COMPREHENSION, QUANTIFICATION, AND VALIDATION 2025.

- Lu, C.; Lu, C.; Lange, R.T.; Foerster, J.; Clune, J.; Ha, D. The AI Scientist: Towards Fully Automated Open-Ended Scientific Discovery, 2024. arXiv:2408. 06292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, P.; Côté, M.A.; Khot, T.; Bransom, E.; Mishra, B.D.; Majumder, B.P.; Tafjord, O.; Clark, P. DISCOVERYWORLD: A Virtual Environment for Developing and Evaluating Automated Scientific Discovery Agents, 2024. arXiv:2406. 06769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, H.; Xu, H.; Xu, R.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Garg, A.; Li, Z.; Ajoudani, A.; Liu, X. Scaling Laws in Scientific Discovery with AI and Robot Scientists, 2025. arXiv:2503. 22444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottweis, J.; Weng, W.H.; Daryin, A.; Tu, T.; Palepu, A.; Sirkovic, P.; Myaskovsky, A.; Weissenberger, F.; Rong, K.; Tanno, R.; et al. Towards an AI co-scientist, 2025. arXiv:2502. 18864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Lange, R.T.; Lu, C.; Hu, S.; Lu, C.; Foerster, J.; Clune, J.; Ha, D. The AI Scientist-v2: Workshop-Level Automated Scientific Discovery via Agentic Tree Search, 2025. arXiv:2504. 08066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelikman, E.; Wu, Y.; Mu, J.; Goodman, N.D. STaR: Bootstrapping Reasoning With Reasoning, 2022. arXiv:2203. 14465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Co-Reyes, J.D.; Agarwal, R.; Anand, A.; Patil, P.; Garcia, X.; Liu, P.J.; Harrison, J.; Lee, J.; Xu, K.; et al. Beyond Human Data: Scaling Self-Training for Problem-Solving with Language Models, 2024. arXiv:2312. 06585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Braza, J.D.; Griffiths, R.R.; Ponnapati, M.; Bou, A.; Laurent, J.; Kabeli, O.; Wellawatte, G.; Cox, S.; Rodriques, S.G.; et al. Aviary: training language agents on challenging scientific tasks, 2024. arXiv:2412. 21154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, M.; Yuan, C.; Tan, C. Literature Meets Data: A Synergistic Approach to Hypothesis Generation, 2025. arXiv:2410. 17309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Jauhar, S.K.; Cucerzan, S.; Hwang, S.J. ResearchAgent: Iterative Research Idea Generation over Scientific Literature with Large Language Models, 2025. arXiv:2404. 07738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidgall, S.; Su, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Wu, J.; Yu, X.; Liu, J.; Moor, M.; Liu, Z.; Barsoum, E. Agent Laboratory: Using LLM Agents as Research Assistants, 2025. arXiv:2501. 04227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, N.; Zhang, B.; Feng, S.; Yan, X.; Yuan, J.; Yu, Z.; He, X.; Huang, S.; Hou, S.; Nie, Z.; et al. NovelSeek: When Agent Becomes the Scientist – Building Closed-Loop System from Hypothesis to Verification, 2025. arXiv:2505. 16938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; He, T.; Hong, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Song, K.; Zhu, K.; et al. Advances and Challenges in Foundation Agents: From Brain-Inspired Intelligence to Evolutionary, Collaborative, and Safe Systems, 2025. arXiv:2504. 01990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wan, X.; Sun, R.; Palangi, H.; Iqbal, S.; Vulić, I.; Korhonen, A.; Arık, S.Ö. Multi-Agent Design: Optimizing Agents with Better Prompts and Topologies.

- Wu, Q.; Bansal, G.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhu, E.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; et al. Autogen: Enabling next-gen llm applications via multi-agent conversation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.08155, 2023; arXiv:2308.08155 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Hammoud, H.; Itani, H.; Khizbullin, D.; Ghanem, B. Camel: Communicative agents for" mind" exploration of large language model society. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 51991–52008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Athiwaratkun, B.; Zhang, C.; Zou, J. Mixture-of-Agents Enhances Large Language Model Capabilities, 2024. arXiv:2406. 04692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, V.; Du, Y.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Torralba, A.; Li, S.; Mordatch, I. Multiagent Finetuning: Self Improvement with Diverse Reasoning Chains, 2025. arXiv:2501. 05707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiang, J.; Yu, Z.; Teng, F.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Zhuge, M.; Cheng, X.; Hong, S.; Wang, J.; et al. AFlow: Automating Agentic Workflow Generation, 2024. arXiv:2410. 10762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Lu, C.; Clune, J. Automated Design of Agentic Systems, 2024. arXiv:2408. 08435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, S.; Lu, C.; Lange, R.; Clune, J. Darwin Godel Machine: Open-Ended Evolution of Self-Improving Agents, 2025. arXiv:2505. 22954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzadeh, I.; Alizadeh, K.; Shahrokhi, H.; Tuzel, O.; Bengio, S.; Farajtabar, M. GSM-Symbolic: Understanding the Limitations of Mathematical Reasoning in Large Language Models, 2024. arXiv:2410. 05229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreivy, N.; Hakim, A. Weak baselines and reporting biases lead to overoptimism in machine learning for fluid-related partial differential equations. Nat Mach Intell 2024, 6, 1256–1269 arXiv:2407.07218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, M.J. Agentic Deep Graph Reasoning Yields Self-Organizing Knowledge Networks, 2025. arXiv:2502. 13025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Clark, P.; Richardson, K. Language Modeling by Language Models, 2025. arXiv:2506. 20249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Q.; Cox, S.; Medina, J.; Watterson, B.; White, A.D. MDCrow: Automating Molecular Dynamics Workflows with Large Language Models, 2025. arXiv:2502. 09565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.; Luyten, M.R.; Schaar, M.v.d. L2MAC: Large Language Model Automatic Computer for Extensive Code Generation, 2024. arXiv:2310. 02003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Cohen, M.; Fornasiere, D.; Ghosn, J.; Greiner, P.; MacDermott, M.; Mindermann, S.; Oberman, A.; Richardson, J.; Richardson, O.; et al. Superintelligent Agents Pose Catastrophic Risks: Can Scientist AI Offer a Safer Path?, 2025. arXiv:2502. 15657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, C.; White, R.W. Agents Are Not Enough, 2024. arXiv:2412. 16241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Peng, H.; Khot, T.; Lapata, M. Improving Language Model Negotiation with Self-Play and In-Context Learning from AI Feedback, 2023. arXiv:2305. 10142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Jia, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhan, W.; Zhang, J.; Wen, X.; Gan, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, Q.; Ma, M.D.; et al. MetaScientist: A Human-AI Synergistic Framework for Automated Mechanical Metamaterial Design, 2024. arXiv:2412. 16270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Wang, X.; Neubig, G.; Jaitly, N.; Ji, H.; Suhr, A.; Zhang, Y. Training Software Engineering Agents and Verifiers with SWE-Gym, 2024. arXiv:2412. 21139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.V.; Shen, X.; Aponte, R.; Xia, Y.; Basu, S.; Hu, Z.; Chen, J.; Parmar, M.; Kunapuli, S.; Barrow, J.; et al. A Survey of Small Language Models, 2024. arXiv:2410.20011.

- Ghaffari, M.; Haeupler, B. Distributed algorithms for planar networks II: low-congestion shortcuts, mst, and min-cut. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the twenty-seventh annual ACM-SIAM symposium on Discrete algorithms.SIAM, 2016, pp. 202–219.

- Yuksekgonul, M.; Bianchi, F.; Boen, J.; Liu, S.; Huang, Z.; Guestrin, C.; Zou, J. TextGrad: Automatic "Differentiation" via Text, 2024. arXiv:2406. 07496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, M.; Kulikov, I.; Bikel, D.M.; Oguz, B.; Chen, X.; Pappu, A. Post-training an LLM for RAG? Train on Self-Generated Demonstrations, 2025. arXiv:2502. 10596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xia, L.; Yu, Y.; Ao, T.; Huang, C. LightRAG: Simple and Fast Retrieval-Augmented Generation, 2024. arXiv:2410. 05779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Samuel, V.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, D. Collaborative Gym: A Framework for Enabling and Evaluating Human-Agent Collaboration, 2025. arXiv:2412. 15701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, H.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D.; Chen, X. Large Language Models as Optimizers, 2024. arXiv:2309. 03409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Shu, X.; Qian, H.; Lu, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, A.; Yu, Y. LLMOPT: Learning to Define and Solve General Optimization Problems from Scratch, 2025. arXiv:2410. 13213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghareeb, A.E.; Chang, B.; Mitchener, L.; Yiu, A.; Szostkiewicz, C.J.; Laurent, J.M.; Razzak, M.T.; White, A.D.; Hinks, M.M.; Rodriques, S.G. Robin: A multi-agent system for automating scientific discovery, 2025. arXiv:2505. 13400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, H.; Ren, Z. OptMetaOpenFOAM: Large Language Model Driven Chain of Thought for Sensitivity Analysis and Parameter Optimization based on CFD, 2025. arXiv:2503. 01273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Somasekharan, N.; Cao, Y.; Pan, S. Foam-Agent: Towards Automated Intelligent CFD Workflows. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.04997 2025, arXiv:2505.04997 2025.

- Yue, L.; Xing, S.; Chen, J.; Fu, T. Clinicalagent: Clinical trial multi-agent system with large language model-based reasoning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology and Health Informatics, 2024, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cao, Y.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hu, P.; Luo, X.; Song, Z.; Zhao, W.; Liu, J.; Sun, J.; et al. Recent Advances on Machine Learning for Computational Fluid Dynamics: A Survey, 2024. arXiv:2408. 12171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Lu, Z.; Yang, Y. Fine-tuning an Large Language Model for Automating Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations, 2025. arXiv:2504. 1: [physics] version, 0960; 09602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, Q.; Yue, L.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zheng, Y. Emerging drug interaction prediction enabled by a flow-based graph neural network with biomedical network. Nature Computational Science 2023, 3, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. Journal of Computational Physics 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Suo, W.; Song, J.; Cao, W. Physics Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) as intelligent computing technique for solving partial differential equations: Limitation and Future prospects, 2024. arXiv:2411. 18240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herde, M.; Raonić, B.; Rohner, T.; Käppeli, R.; Molinaro, R.; Bézenac, E.d.; Mishra, S. Poseidon: Efficient Foundation Models for PDEs, 2024. arXiv:2405. 19101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; George, R.J.; Elleithy, M.; Leibovici, D.; Li, Z.; Bonev, B.; White, C.; Berner, J.; Yeh, R.A.; Kossaifi, J.; et al. Pretraining Codomain Attention Neural Operators for Solving Multiphysics PDEs, 2024. arXiv:2403. 12553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuwu, Q.; Gao, C.; Chen, T.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, S. PINNsAgent: Automated PDE Surrogation with Large Language Models, 2025. arXiv:2501. 12053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lin, R.; Yu, B.; Liu, D.; Zhou, J.; Lin, J. The Lessons of Developing Process Reward Models in Mathematical Reasoning, 2025. arXiv:2501. 07301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeepSeek-AI. ; Guo, D.; Yang, D., Zhang, H., Song, J., Zhang, R., Xu, R., Zhu, Q., Ma, S., Wang, P., Eds.; et al. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning, arXiv:2501.12948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.L.; Juergens, D.; Bennett, N.R.; Trippe, B.L.; Yim, J.; Eisenach, H.E.; Ahern, W.; Borst, A.J.; Ragotte, R.J.; Milles, L.F.; et al. De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature 2023, 620, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambaldi, V.; La, D.; Chu, A.E.; Patani, H.; Danson, A.E.; Kwan, T.O.C.; Frerix, T.; Schneider, R.G.; Saxton, D.; Thillaisundaram, A.; et al. De novo design of high-affinity protein binders with AlphaProteo, 2024. arXiv:2409. 08022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, M.A.; Tekin, E.; Nadeem, M.; ElNaker, N.A.; Singh, A.; Vassilieva, N.; Amor, B.B. Prot42: a Novel Family of Protein Language Models for Target-aware Protein Binder Generation, 2025. arXiv:2504. 04453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazgir, A.; Zhang, Y. PROTEINHYPOTHESIS: A PHYSICS-AWARE CHAIN OF MULTI-AGENT RAG LLM FOR HYPOTHESIS GENER- ATION IN PROTEIN SCIENCE 2025.

- Messeri, L.; Crockett, M.J. Artificial intelligence and illusions of understanding in scientific research. Nature 2024, 627, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, T.; Pruthi, D. All That Glitters is Not Novel: Plagiarism in AI Generated Research, 2025. arXiv:2502. 16487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcak, P.; Heinrich, G.; Diao, S.; Fu, Y.; Dong, X.; Muralidharan, S.; Lin, Y.C.; Molchanov, P. Small Language Models are the Future of Agentic AI, 2025. arXiv:2506. 02153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, F.; Madireddy, S.; Underwood, R.; Getty, N.; Chia, N.L.P.; Ramachandra, N.; Nguyen, J.; Keceli, M.; Mallick, T.; Li, Z.; et al. EAIRA: Establishing a Methodology for Evaluating AI Models as Scientific Research Assistants, 2025. arXiv:2502. 20309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.F.; Choquette-Choo, C.A.; Bogen, M.; Jagielski, M.; Filippova, K.; Liu, K.Z.; Chouldechova, A.; Hayes, J.; Huang, Y.; Mireshghallah, N.; et al. Machine Unlearning Doesn’t Do What You Think: Lessons for Generative AI Policy, Research, and Practice, 2024. arXiv:2412. 06966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).