1. Introduction

“Science is a collaborative effort. The combined results of several people working together is often much more effective than an individual scientist working alone.”

Automating scientific discovery has evolved through technological epochs driven by advancing artificial intelligence reasoning capabilities. Pioneering systems like

Adam [

1] proposed closing hypothesis-experiment cycles through robot scientists, while deep learning breakthroughs produced landmark achievements including

AlphaFold [

2] for protein structure prediction and

AlphaProof [

3] for mathematical reasoning, drastically accelerating discovery across diverse domains by solving previously intractable problems with high accuracy and efficiency.

The rise of large language models have further catalyzed a paradigm shift where AI systems evolved from assistive tools [

4,

5] toward autonomous agents [

6,

7,

8] emulating independent researchers. These systems advance research across physics [

9,

10], biochemistry [

11,

12,

13,

14], causal discovery [

15], social sciences [

16,

17], and clinical diagnosis [

18,

19], demonstrating broad AI-driven scientific capabilities that integrate domain knowledge with adaptive reasoning to tackle multifaceted challenges.

Recent breakthroughs of

Grok-4-Heavy [

20] and

Gemini-DeepThink [

21] explored multi-agent schema [

22,

23] to mirror collective reasoning dynamic of human research teams, achieving leading performance on challenging benchmarks including the International Mathematical Olympiad

2 and Humanity’s Last Exam [

24]. This progress signals a promising transition from single-agent systems toward MAS architectures reflecting the collaborative intelligence underlying human scientific discovery, where emergent group dynamics enable superior problem-solving through division of labor and iterative refinement.

Despite these advances, existing efforts remain fragmented across domains and isolated tasks, lacking a holistic view of MAS potential in end-to-end research workflows. We aim to address this gap through a comprehensive analysis that delineates MAS advantages in collective reasoning, confronts current limitations in practical deployment, and outline a roadmap of future work directions to bridge these gaps towards transforming MAS from promising prototypes into reliable co-scientists as research companion.

Organizational Structure

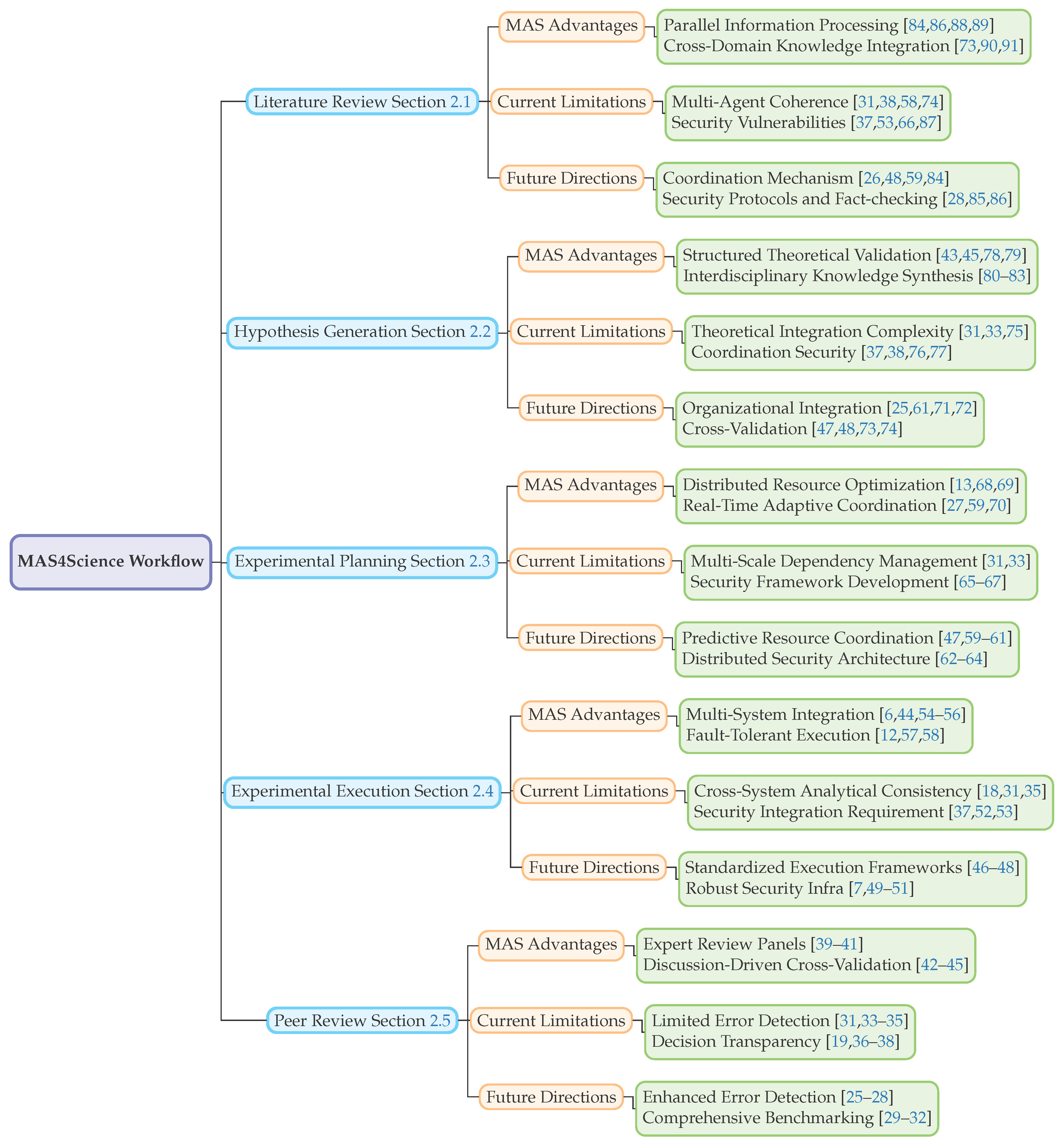

We introduce a comprehensive application-oriented taxonomy structured around three core analytical dimensions: first, we examine the advantages of multi-agent versus single-agent systems across five key stages of the research workflow (sec:masworkflow); second, we analyze the current reality and fundamental bottlenecks limiting MAS deployment in scientific discovery (sec:realitybottlenecks); and third, we outline strategic future work directions toward realizing the full potential of MAS for science (sec:futuredirections).

Paper Selection

Given the rapid evolution of MAS, we prioritize recent studies highlighting their unique advantages and challenges in scientific applications. We focus on works that compare multi-agent and single-agent systems, ensuring relevance by continuously updating our analysis to reflect the latest advancements in AI architectures and their scientific applications.

2. Advantages of Multi vs. Single Agent Systems in Scientific Research Workflow

We propose an application-oriented taxonomy, illustrated in

Figure 1, that maps MAS capabilities to five canonical research workflow stages: literature review (

Section 2.1), hypothesis generation (

Section 2.2), experimental planning (

Section 2.3), experimental execution (

Section 2.4), and peer review (

Section 2.5). In this section, we map the unique potential brought by MAS in comparison to conventional single agents to the 5 key stages.

2.1. Literature Review

The literature review stage establishes foundational knowledge by systematically identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing existing research to map current understanding and pinpoint knowledge gaps. With rapidly growing scientific papers published annually, this process overwhelms traditional human-centered approaches due to the sheer volume and complexity of interdisciplinary data.

Parallel Knowledge Processing

The fundamental advantage of MAS over single-agent systems lies in their ability to decompose the cognitive burden of literature analysis across specialized components, thereby achieving unprecedented scale and depth. This distributed architecture enables MAS to orchestrate retrieval agents with domain-specific strategies through multi-agent systematic reviews [

92], while fact-checking agents ensure cross-validation accuracy [

86]. Knowledge integration agents construct semantic networks revealing interdisciplinary connections, such as linking bacterial quorum sensing to neural network synchronization via knowledge graphs [

84]. Scientific multi-agent systems demonstrate this capability in computational biology, enabling concurrent analysis of molecular dynamics, gene regulatory networks, and phylogenetic relationships [

22]. The distributed processing architecture mitigates inherent biases through knowledge-enhanced frameworks [

88] and delivers insights unattainable through sequential processing via simulated expert discussions [

89].

Cross-Domain Knowledge Integration

Beyond parallel processing capabilities, MAS excel at synthesizing knowledge across disciplinary boundaries where single agents typically fail due to domain-specific training limitations. This synthesis advantage stems from specialized agents maintaining distinct perspectives while collaborating on unified integration tasks. Graph-based representations facilitate insight integration from earth science applications [

90] to drug discovery [

91], uncovering emergent patterns invisible to single-domain approaches. Coordination frameworks ensure comprehensive coverage through distributed teams [

73], creating cohesive knowledge bases that bridge disciplinary boundaries. This interdisciplinary synthesis establishes the foundation for creative hypothesis generation by providing a unified knowledge base that transcends traditional academic silos.

2.2. Hypothesis Generation

Hypothesis generation involves formulating testable propositions to advance theoretical understanding by synthesizing diverse information sources and identifying novel research questions. This stage requires divergent thinking to explore innovative possibilities and convergent reasoning to ensure theoretical coherence, balancing creativity with rigor. Effective hypothesis generation integrates insights from multiple disciplines to propose hypotheses that are both original and empirically grounded.

Structured Theoretical Validation

MAS provide a systematic approach to hypothesis refinement through adversarial validation that single agents cannot replicate due to their inherent confirmation bias. This validation advantage emerges through debate systems that rigorously challenge propositions using large language model debates [

43], while conditional effect evaluation refines hypotheses by testing diverse assumptions [

45]. Adversarial frameworks emulate distributed peer review during creative phases [

78], iteratively refining constructs through cooperative reinforcement learning [

79]. The systematic validation process produces theoretically robust hypotheses that withstand rigorous multi-perspective critique, preparing them for interdisciplinary synthesis applications.

Interdisciplinary Knowledge Synthesis

The breakthrough potential of MAS emerges when they synthesize theoretical frameworks across previously isolated domains, creating novel scientific hypotheses impossible for single-domain agents. Building on structured validation capabilities, MAS achieve breakthrough hypothesis generation by deploying specialized ensembles that maintain theoretical rigor while exploring novel cross-domain connections. Physics agents combine quantum field theory, relativity, and condensed matter physics through multi-agent code generation [

80], while principle-aware frameworks maintain coherence through critic-refine cycles [

81]. Drug discovery applications demonstrate collaborative hypothesis generation through agent swarms [

82] and autonomous molecular design [

83]. This theoretical synthesis creates foundations for complex experimental planning by generating testable hypotheses that span multiple scientific domains.

2.3. Experimental Planning

Experimental planning transforms hypotheses into actionable protocols by designing procedures, allocating resources, and coordinating timelines across potentially multiple institutions. This stage involves selecting methodologies, determining parameters, and managing complex interdependencies, with challenges scaling exponentially as variables and constraints increase. Effective planning requires optimization under uncertainty to ensure feasibility and efficiency.

Distributed Resource Optimization

MAS fundamentally transform experimental planning by decomposing complex optimization problems that overwhelm single agents, particularly when dealing with multi-institutional and multi-domain experiments. The distributed optimization advantage stems from specialized agents handling different aspects of resource allocation simultaneously. MULTITASK [

68] frameworks enable efficient allocation across heterogeneous laboratory environments, while chemical coordination systems manage complex workflows through collaborative processing [

13]. Astrophysical applications [

4] demonstrate adaptive resource allocation capabilities through OpenMAS platforms [

69], which enable efficient resource re-allocation capable of dynamic response to experimental demands.

Real-Time Adaptive Coordination

The key advantage of MAS in experimental planning lies in their ability to maintain multiple contingency plans simultaneously and adapt instantly to changing experimental conditions. Building on distributed optimization with multiple agents, MAS achieve superior planning through redundant coordination agents that enable continuous adaptation to uncertainties that overwhelm single-agent systems, which effectively serves as autonomous error-correction in the latent space. Autonomous frameworks respond immediately to experimental changes through parallel planning systems [

70], while multi-agent reinforcement learning maintains experimental resilience [

59]. Fault detection MAS [

27] monitor and dynamically adjust resource allocations across complex experimental pipelines, which ensures output while offering robust contingency planning that maintains experimental integrity under uncertainty.

2.4. Experimental Execution

Experimental execution implements planned protocols by coordinating instrumentation, computational resources, and data collection systems to generate empirical evidence. This stage demands precise control of experimental conditions, real-time monitoring, adaptive responses to anomalies, and integration of diverse data streams for interpretation.

Multi-System Integration

MAS provide unique advantages in experimental execution by coordinating heterogeneous systems through different model communication protocols enabled by different agents. DeepMind [

54,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97] demonstrate how specialized agents can leverage code generation to excel in highly specified niche tasks, while self-reflective frameworks coordinate distributed components [

55]. Paper-to-code systems bridge theoretical predictions with experimental validation [

44] and aim to further handle multimodal data streams [

56]. El Agente [

6] showcased comprehensive experimental automation in quantum chemistry via hierarchical memory framework that enables flexible task decomposition, adaptive tool selection, results analysis, and maintain detailed action trace logs across various systems.

Fault-Tolerant Execution

The distributed nature of MAS naturally enable fault tolerance through redundant agents and automatic backoff mechanisms that that addresses workflow vulnerabilities systematically. Biomedical MAS [

12,

57] can coordinate robotic-based lab instrumentation and analysis systems while maintaining experimental continuity even if some component collapsed during this process. Knowledge conflict [

58] with inconsistent data can be resolved through discussion-driven mutual reasoning. In summary, MAS sets a foundation for fault-tolerant execution that produces more reliable experimental data with real-time peer review with error-detecting agents and provide clear logs to tract any failures to ensure experimental rigor.

2.5. Peer Review

Peer review serves as a critical quality control for scientific research by mutually evaluating methodology, analysis, contributions, and ethical compliance within the same community. This stage assesses the rigor of experimental design, statistical analysis and result interpretation. With rapidly increasing research volume and complexity in the field of artificial intelligence, the heavy pressure on human reviewers can potentially be alleviated by training trustworthy MAS for preliminary screening while leaving the most vital decision-making to seasoned experts as area chairs.

Expert Review Panels

MAS revolutionize peer review by deploying domain experts simultaneously while eliminating the scheduling and coordination challenges that plague human review panels. The specialized panel advantage emerges from MAS deploying multiple domain experts who evaluate research from diverse perspectives simultaneously, eliminating cognitive biases inherent in individual review processes. Agent-based systems coordinate methodology and expertise assessments [

39], while deep review systems leverage parallel evaluation for comprehensive research scrutiny [

40]. Dynamic frameworks adapt review protocols based on research complexity [

41]. This specialized review approach establishes foundations for redundant validation by providing comprehensive multi-expert assessment that surpasses traditional review limitations.

Discussion-Driven Cross-Validation

The ultimate strength of MAS in peer review lies in their ability to provide multiple independent validations simultaneously, creating a level of scrutiny impossible with sequential single-agent approaches. Building on specialized panel infrastructure, MAS enhance quality control through cross-validation that systematically verifies research claims beyond single-agent capabilities. Insights from such panel discussion can further inform iterative refinement as shown in CycleResearcher [

42]. Furthermore, the approach implements robust quality assurance measures, ensuring that the knowledge generated meets rigorous standards of scientific research. By meticulously scrutinizing the data and methodologies employed, the quality assurance protocols contribute to the reliability and validity of the research outcomes, thereby enhancing knowledge reliability for future cycles.

3. Current Reality and Key Bottlenecks of MAS in Scientific Discovery

Coordination and Communication Failures

MAS face fundamental coordination challenges manifested as both naturally arising semantic incoherence and potential communication vulnerabilities in the face of adversarial injection. The coherence problem emerges from semantic fragmentation where agents trained on highly specialized niche corpora develop drastically different conceptual frameworks, leading to misinterpretation of cross-domain terminology and fragmented meta-analyses [

30]. These inconsistencies could create many incompatible knowledge bases lacking semantic unity necessary for reliable interdisciplinary knowledge synthesis [

58].Communication vulnerabilities further compound this challenge when adversarial agents or prompt injection exploit coordination protocols, manipulating the equal footing of multi-agent discussion mechanisms to skew research propositions through sophisticated attacks [

38,

77]. This conflict boils down to the fundamental trade-offs between achieving collaborative benefits from mutual discussion and robust system reliability through centralized decision-making. One direction for future investigation might explore

assigning different weights to the opinion of different agents based on their robustness score against adversarial attacks and vulnerability score in the face of misalignment temptation.

Security Risks

MAS with distributed architecture could lead to expanded attack surfaces that expose scientific workflows to sophisticated manipulation attempts absent in centralized systems. Malicious agents can inject misinformation that propagates through collaborative networks, exploiting trust mechanisms to bias literature selection and hypothesis generation processes [

37,

58]. The sophistication of potential attacks extends to domain-specific vulnerabilities, as demonstrated in materials research where adversaries exploit specialized knowledge to compromise research integrity [

63]. Adversarial challenges manifest when malicious agents create deliberate deadlocks that manipulate resource allocation processes [

65], while expanded communication infrastructure creates multiple attack vectors [

67]. Defending against such attacks requires cryptographic verification and behavioral monitoring systems that approach the complexity of the scientific applications themselves [

66], creating significant computational overhead while the distributed nature provides adversaries with multiple entry points for system compromise.

Integration and Scalability Limitations

MAS struggle with highly complex theoretical integration and multi-scale dependency management that often make distributed approaches less efficient than single-agent alternatives. The integration challenge stems from coordination complexity in reconciling diverse theoretical models, producing superficial knowledge aggregation rather than genuine synthesis necessary for scientific breakthroughs [

29,

31]. Current architectures lack frameworks for theoretical unification [

75], while coordination bottlenecks prevent deep integration [

33]. Multi-scale dependency management compounds these issues when local optimization decisions create global inefficiencies that undermine experimental protocols [

31], with heterogeneous resource coordination introducing complexities beyond capacity for simpler single-agent to manage concurrently [

68]. Coordination conflicts can create cascading failures that propagate through distributed architectures, which is a key bottleneck to unify conceptual understanding necessary for interdisciplinary investigation.

Interoperability and Transparency Deficits

MAS suffer from interoperability issues and decision opacity that undermine scientific accountability standards. Heterogeneous systems could create persistent inconsistencies in scientific data processing, with platform-specific variations challenging critical high-stake application fields like healthcare diagnostics [

18] and biomedical research [

11,

12]. These inconsistencies contrast with centralized control consistency [

31], requiring standardized protocols that remain an open challenge. Error detection limitations compound when distributed architectures lack concentrated domain expertise necessary for identifying subtle scientific flaws [

34,

35], while security integration creates additional complexity [

37,

52]. Decision transparency suffers from coordination complexity that makes decisions difficult to trace and audit [

36], while potential coordinated bias injection compromises transparency [

19]. The distributed processing that enables collaborative analysis simultaneously obscures decision tractability and methodological clarity.

4. Future Directions Towards Multi-Agent AI Scientists for Scientific Discovery

Organizational Integration

Future MAS requires foundational organizational frameworks that transform separate agents into coherent collaboration through structured protocols [

26], where knowledge graphs [

84] provide promising prospects for optimization of agent network structure based on organizational theory [

25] and offer grounds for co-evolutionary learning [

71,

79]. This organizational infrastructure enables cross-task learning based on experience [

61] with critic feedback systems [

72], which generates integrative hypotheses that transcend disciplinary boundaries through adaptive organizational structures that mirror human team dynamics [

59]. Domain generalization capabilities [

48] facilitate knowledge transfer while they preserve domain-specific expertise, supported by autonomous research-to-paper frameworks [

49] and cross-team orchestration mechanisms [

73]. Critical future agenda include the implementation of standardized frameworks for cross-domain integration, establishment of hierarchical validation protocols, and creation of adaptive organizational structures that balance different perspective with robust mechanism to reach consensus. These organizational foundations provide the structural basis for subsequent security infrastructure development.

Security Protocol and Infrastructure

Comprehensive security architectures must address vulnerability challenges through consensus mechanisms while they preserve collaborative functionality essential for distributed research. The security layer should integrate peer-guard protocols against backdoor attacks [

28] with fact-checking MAS that provides additional cross-validation through multiple-layered verification performed by various agents [

86]. Zero-trust architectures limit attack surfaces through continuous authentication [

85] with differential privacy techniques that protect sensitive research information [

62]. Advanced behavioral analysis systems provide real-time anomaly detection [

63], supported by deadlock prevention mechanisms that enhance system resilience against adversarial attacks [

64]. Privacy-preserving mechanisms [

52] integrate with manipulation safeguards to create tamper-resistant validation frameworks that maintain scientific integrity without compromising collaborative functionality [

66]. Essential development initiatives include the implementation of cryptographic consensus protocols, development of behavioral monitoring systems that detect subtle manipulation attempts, and creation of security frameworks that scale with research collaboration complexity while they preserve trust relationships.

Robust Cross-Validation

Secure infrastructure enables future MAS scientists to implement comprehensive validation that fosters mutual reasoning through active discussion and constructive critique [

98], while reproducibility benchmarks ensure empirical alignment across diverse scientific methodologies [

74,

99]. Domain-generalization frameworks enhance robustness testing capabilities [

48], which address integration challenges through knowledge synthesis protocols [

47] and full-spectrum research quality evaluation frameworks [

29] on output quality, efficiency and robustness across different agentic capacities that span theorists, experimentalists and computational scientists. Cross-domain knowledge discovery approaches [

100] complement virtual scientific idea generation systems [

101] to create comprehensive evaluation frameworks. Key development priorities include establishment of multi-modal validation frameworks that integrate theoretical consistency verification with experimental validation, and creation of automated reproducibility-checking agents that detect subtle inconsistencies across diverse scientific methodologies while they provide transparent audit trails. This validation infrastructure directly informs adaptive resource allocation through quality metrics for operation optimization decision-making.

Adaptive Resource Allocation

Resource allocation MAS for experimental execution should employ parallel simulations that model multiple experimental protocols to identify potential conflicts and bottlenecks [

59], while various agents can provide insights to inform generalizable allocation strategies across diverse experimental contexts based on cross-validation feedback [

61]. Real-time monitoring enables dynamic adjustment through virtual laboratory environments [

60], which ensures efficient experimental plans through comprehensive coordination [

47] that surpasses single-agent dependency handling [

68]. Agent-oriented planning frameworks [

102] complement parallel simulation systems [

103] to create robust resource management architectures. The system integrates validation quality metrics to prioritize high-confidence research directions while it maintains resource efficiency across multi-institutional collaborations. Research initiatives must focus on development of predictive resource allocation algorithms that anticipate experimental dependencies and conflicts, implementation of real-time adaptation mechanisms that dynamically rebalance resources based on changing experimental conditions and validation outcomes, and creation of virtual laboratory frameworks that enable comprehensive experimental protocol validation before physical resource commitment. This adaptive allocation system provides the foundation for standardized execution across heterogeneous environments.

Standardized Execution Frameworks

Resource-optimized allocation enables universal integration standards that facilitate seamless coordination across heterogeneous research environments through comprehensive interoperability protocols which address system inconsistencies. The standardization framework implements semantic interoperability mechanisms that handle vendor-specific differences while adaptation protocols adjust to system variations [

46]. Comprehensive cross-domain knowledge bases [

48] support integrated execution systems [

47] that enable failure-resistant operation, which establishes robust alternatives for complex biomedical applications [

12]. Self-reflective multi-agent frameworks [

55] enhance code generation capabilities while paper-to-code systems bridge theoretical predictions with practical implementations [

44,

56]. Fault detection systems predict and mitigate potential disruptions [

27], while deadlock detection mechanisms enhance overall system resilience [

65], which builds on resource allocation optimization to prevent coordination conflicts. Privacy-preserving data protection mechanisms [

53] should integrate with distributed verification multi-agent reinforcement learning [

52] to provide standardized interfaces that maintain consistency across diverse scientific computing environments. Development priorities include creation of universal semantic translation protocols that enable seamless communication between heterogeneous scientific systems, implementation of standardized fault tolerance mechanisms that maintain experimental continuity across system failures, and establishment of comprehensive interoperability testing frameworks that ensure consistent scientific results across diverse computational platforms.

Enhanced Error Detection and Benchmarking

Standardized execution frameworks enable comprehensive evaluation systems that leverage distributed domain expertise for enhanced error detection which addresses transparency and reliability limitations. Detection system should integrate deep domain expertise with multi-dimensional evaluation frameworks that encompass theoretical, methodological, and empirical assessment criteria, which builds upon standardized execution protocols to ensure consistent evaluation across platforms. By synthesizing questions from real-world research papers, future benchmarks should test diverse agentic capacities [

29] in high-fidelity research scenarios with experimental platforms that evaluate practical research performance [

31] and multi-modal tasks that incorporate data streams of various modalities [

104]. Research-based evaluation suites [

30] integrate with comprehensive reproducibility assessments [

32,

99] bear the potential to automate executable validation to enhance reliability of research publications as a whole. Principle-aware scientific discovery frameworks [

81] complement conditional effectiveness studies [

45] to enhance rigor of validation results. Future MAS should establish domain-specific error detection protocols that identify subtle scientific flaws by integrating expert opinion from human reviewers [

105], implement transparent decision auditing systems that provide clear explanations for human-AI collaboration [

106], and create comprehensive benchmarking frameworks that measure MAS effectiveness across complete scientific research pipelines. This integrated approach further close the evaluation-verification-optimization cycle where benchmarking validation results subsequently inform iterative refinement, which ultimately establishes a robust MAS4Science ecosystem capable of providing genuine scientific discovery on open-ended research questions.

5. Vision and Conclusion

The evolution from single-agent to multi-agent systems for scientific discovery represents a foundational paradigm shift from AI as only tools to collaborative intelligence networks that take inspirations from how human researchers attempt to expand knowledge frontiers into the unknowns. As these systems mature from current promising prototypes into actually functional research ecosystems, they promise to unlock capabilities that transcend current single-agent limitations of memory and context window to perform open-ended reasoning through discussion-driven mutual reasoning and parallel exploration of vast state spaces. The vision extends beyond mere automation toward enabling new forms of human-AI collaborative inquiry where AI agents serve as autonomous co-scientists with refreshing perspective alongside human researchers.

6. Limitations

This survey provides an overview of the current reality and future prospects of MAS for scientific discovery (MAS4Science). However, certain limitations in the scope and methodology of this paper warrant acknowledgment.

References and Methods

Due to page limits, this survey may not capture all relevant literature, particularly given the rapid evolution of both multi-agent and AI4Science research. We focus on frontier works published between 2023 and 2025 in leading venues, including conferences such as *ACL, ICLR, ICML, and NeurIPS, and journals like Nature, Science, and IEEE Transactions. Ongoing efforts will monitor and incorporate emerging studies to ensure the survey remains current.

Empirical Conclusions

Our analysis and proposed directions rely on empirical evaluations of existing MAS frameworks, which may not fully capture the field’s macroscopic dynamics. The rapid pace of advancements risks outdating certain insights, and our perspective may miss niche or emerging subfields. We commit to periodically updating our assessments to reflect the latest developments and broader viewpoints.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Despite our best effort to responsibly synthesize the current reality and future prospects at the intersection of AI4Science and Multi-Agent Research, ethical challenges remain as the selection of literature may inadvertently favor more prominent works, and may potentially overlook contributions from underrepresented research communities. We aim to uphold rigorous standards in citation practices and advocate for transparent, inclusive research to mitigate these risks.

Acknowledgments

This material is based in part upon work supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF): Tübingen AI Center, FKZ: 01IS18039B; by the Machine Learning Cluster of Excellence, EXC number 2064/1 – Project number 390727645; by Schmidt Sciences SAFE-AI Grant; by NSERC Discovery Grant RGPIN-2025-06491; by Cooperative AI Foundation; by the Survival and Flourishing Fund; by a Swiss National Science Foundation award (#201009) and a Responsible AI grant by the Haslerstiftung.

References

- King, R.; Whelan, K.E.; Jones, F.; Reiser, P.G.K.; Bryant, C.H.; Muggleton, S.; Kell, D.; Oliver, S. Functional genomic hypothesis generation and experimentation by a robot scientist. Nature 2004, 427, 247–252.

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [CrossRef]

- DeepMind, G. AI achieves silver-medal standard solving International Mathematical Olympiad problems, 2024.

- Xu, X.; Bolliet, B.; Dimitrov, A.; Laverick, A.; Villaescusa-Navarro, F.; Xu, L.; Íñigo Zubeldia. Evaluating Retrieval-Augmented Generation Agents for Autonomous Scientific Discovery in Astrophysics. arXiv preprint 2025, [2507.07155].

- Wang, H.; Fu, T.; Du, Y.; Gao, W.; Huang, K.; Liu, Z.; Chandak, P.; Liu, S.; Katwyk, P.V.; Deac, A.; et al. Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature 2023, 620, 47–60.

- Zou, Y.; Cheng, A.H.; Aldossary, A.; Bai, J.; Leong, S.X.; Campos-Gonzalez-Angulo, J.A.; Choi, C.; Ser, C.T.; Tom, G.; Wang, A.; et al. El Agente: An Autonomous Agent for Quantum Chemistry, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2505.02484].

- Lu, C.; Lu, C.; Lange, R.T.; Foerster, J.; Clune, J.; Ha, D. The AI Scientist: Towards Fully Automated Open-Ended Scientific Discovery, 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2408.06292].

- Gottweis, J.; Weng, W.H.; Daryin, A.; Tu, T.; Palepu, A.; Sirkovic, P.; Myaskovsky, A.; Weissenberger, F.; Rong, K.; Tanno, R.; et al. Towards an AI co-scientist, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2502.18864].

- Sarkar, M.; Bolliet, B.; Dimitrov, A.; Laverick, A.; Villaescusa-Navarro, F.; Xu, L.; Íñigo Zubeldia. Multi-Agent System for Cosmological Parameter Analysis. arXiv preprint 2024, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2412.00431].

- Lu, S.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, T.J.; Kos, P.; Cirac, J.I.; Schölkopf, B. Can Theoretical Physics Research Benefit from Language Agents?, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2506.06214].

- Jin, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Cong, L. STELLA: Self-Evolving LLM Agent for Biomedical Research. arXiv preprint 2025, [2507.02004].

- Gao, S.; Fang, A.; Lu, Y.; Fuxin, L.; Shao, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zou, C.; Schneider, J.; Chen, L.; Liu, C.; et al. Empowering biomedical discovery with AI agents. Cell 2024, 187, 6125–6151. [CrossRef]

- Boiko, D.A.; MacKnight, R.; Kline, B.; Gomes, G. Autonomous chemical research with large language models. Nature 2023, 624, 570–578. [CrossRef]

- Bran, A.M.; Cox, S.; Schilter, O.; Baldassari, C.; White, A.D.; Schwaller, P. Augmenting large language models with chemistry tools. Nature Machine Intelligence 2024, 6, 525–535. Published 08 May 2024, . [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Acharya, S.; Simko, S.; Bhardwaj, D.; Haghighat, A.; Sachan, M.; Janzing, D.; Schölkopf, B.; Jin, Z. Causal AI Scientist: Facilitating Causal Data Science with Large Language Models. Manuscript Under Review 2025.

- Haase, J.; Pokutta, S. Beyond Static Responses: Multi-Agent LLM Systems as a New Paradigm for Social Science Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.01839.

- Parkes, D.C.; Wellman, M.P. Economic reasoning and artificial intelligence. Science 2015, 349, 267 – 272.

- Chen, X.; Yi, H.; You, M.; Liu, W.Z.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y. Enhancing diagnostic capability with multi-agents conversational large language models. NPJ Digital Medicine 2025, 8, 65. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.X.; Hong, S. ArgMed-Agents: Explainable Clinical Decision Reasoning with LLM Disscusion via Argumentation Schemes. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM) 2024, pp. 5486–5493.

- xAI. Introducing Grok-4. https://x.ai/news/grok-4, 2025.

- DeepMind. Advanced version of Gemini with Deep Think officially achieves gold-medal standard at the International Mathematical Olympiad, 2025. DeepMind Blog Post.

- Ghafarollahi, A.; Buehler, M.J. SciAgents: Automating scientific discovery through multi-agent intelligent graph reasoning. arXiv preprint 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2409.05556].

- Ghareeb, A.E.; Chang, B.; Mitchener, L.; Yiu, A.; Warner, C.; Riley, P.; Krstic, G.; Yosinski, J. Robin: A Multi-Agent System for Automating Scientific Discovery. arXiv preprint 2025, [2505.13400].

- Phan, L.; Gatti, A.; Han, Z.; Li, N.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.B.C.; Shaaban, M.; Ling, J.; Shi, S.; et al. Humanity’s Last Exam, 2025, [arXiv:cs.LG/2501.14249].

- Borghoff, U.M.; Bottoni, P.; Pareschi, R. An Organizational Theory for Multi-Agent Interactions Integrating Human Agents, LLMs, and Specialized AI. Discover Computing 2025.

- Yan, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Miao, D.; Li, C. Beyond Self-Talk: A Communication-Centric Survey of LLM-Based Multi-Agent Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2502.14321.

- Khalili, M.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y. Multi-Agent Systems for Model-based Fault Diagnosis. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 1211–1216. [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Li, X. PeerGuard: Defending Multi-Agent Systems Against Backdoor Attacks Through Mutual Reasoning. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.11642.

- Chen, H.; Xiong, M.; Lu, Y.; Han, W.; Deng, A.; He, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hooi, B. MLR-Bench: Evaluating AI Agents on Open-Ended Machine Learning Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.19955.

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xie, T.; Ni, J.; Gao, B.; Li, Y.; Tang, S.; Ouyang, W.; Cambria, E.; Zhou, D. ResearchBench: Benchmarking LLMs in Scientific Discovery via Inspiration-Based Task Decomposition. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.21248.

- Kon, P.T.J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, X.; Ding, Q.; Peng, J.; Xing, J.; Huang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Srinivasa, J.; Lee, M.; et al. EXP-Bench: Can AI Conduct AI Research Experiments? ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.24785.

- Siegel, Z.S.; Kapoor, S.; Nagdir, N.; Stroebl, B.; Narayanan, A. CORE-Bench: Fostering the Credibility of Published Research Through a Computational Reproducibility Agent Benchmark. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. 2024, 2024.

- Son, G.; Hong, J.; Fan, H.; Nam, H.; Ko, H.; Lim, S.; Song, J.; Choi, J.; Paulo, G.; Yu, Y.; et al. When AI Co-Scientists Fail: SPOT-a Benchmark for Automated Verification of Scientific Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.11855.

- L’ala, J.; O’Donoghue, O.; Shtedritski, A.; Cox, S.; Rodriques, S.G.; White, A.D. PaperQA: Retrieval-Augmented Generative Agent for Scientific Research. ArXiv 2023, abs/2312.07559.

- Starace, G.; Jaffe, O.; Sherburn, D.; Aung, J.; Chan, J.S.; Maksin, L.; Dias, R.; Mays, E.; Kinsella, B.; Thompson, W.; et al. PaperBench: Evaluating AI’s Ability to Replicate AI Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.01848.

- Li, G.; Hammoud, H.; Itani, H.; Khizbullin, D.; Ghanem, B. CAMEL: Communicative Agents for "Mind" Exploration of Large Language Model Society. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023.

- Zheng, C.; Cao, Y.; Dong, X.; He, T. Demonstrations of Integrity Attacks in Multi-Agent Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.04572.

- Amayuelas, A.; Yang, X.; Antoniades, A.; Hua, W.; Pan, L.; Wang, W. MultiAgent Collaboration Attack: Investigating Adversarial Attacks in Large Language Model Collaborations via Debate. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2024.

- Jin, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhu, K.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, J. AgentReview: Exploring Peer Review Dynamics with LLM Agents. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2024, Miami, FL, USA, November 12-16, 2024; Al-Onaizan, Y.; Bansal, M.; Chen, Y., Eds. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, pp. 1208–1226. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Weng, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y. DeepReview: Improving LLM-based Paper Review with Human-like Deep Thinking Process. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.08569.

- Yu, W.; Tang, S.; Huang, Y.; Dong, N.; Fan, L.; Qi, H.; Guo, C. Dynamic Knowledge Exchange and Dual-Diversity Review: Concisely Unleashing the Potential of a Multi-Agent Research Team. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.18348 2025.

- Weng, Y.; Zhu, M.; Bao, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L. CycleResearcher: Improving Automated Research via Automated Review. ArXiv 2024, abs/2411.00816.

- Du, Y.; Li, S.; Torralba, A.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Mordatch, I. Improving Factuality and Reasoning in Language Models through Multiagent Debate. In Proceedings of the Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2024, Vienna, Austria, July 21-27, 2024, 2024.

- Seo, M.; Baek, J.; Lee, S.; Hwang, S.J. Paper2Code: Automating Code Generation from Scientific Papers in Machine Learning. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.17192.

- Yang, Y.; Yi, E.; Ko, J.; Lee, K.; Jin, Z.; Yun, S. Revisiting Multi-Agent Debate as Test-Time Scaling: A Systematic Study of Conditional Effectiveness. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.22960.

- Perera, R.; Basnayake, A.; Wickramasinghe, M. Enhancing LLM-Based Multi-Agent Systems Through Dynamic Integration of Agents. SSRN 2025.

- Tang, X.; Qin, T.; Peng, T.; Zhou, Z.; Shao, D.; Du, T.; Wei, X.; Xia, P.; Wu, F.; Zhu, H.; et al. Agent KB: Leveraging Cross-Domain Experience for Agentic Problem Solving, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2507.06229].

- Surabhi, P.S.M.; Mudireddy, D.R.; Tao, J. ThinkTank: A Framework for Generalizing Domain-Specific AI Agent Systems into Universal Collaborative Intelligence Platforms. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.02931.

- Ifargan, T.; Hafner, L.; Kern, M.; Alcalay, O.; Kishony, R. Autonomous LLM-driven research from data to human-verifiable research papers. ArXiv 2024, abs/2404.17605.

- Schmidgall, S.; Moor, M. AgentRxiv: Towards Collaborative Autonomous Research. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.18102.

- Zhang, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, D.; Zhou, Z.; An, D. OriGene: A Self-Evolving Virtual Disease Biologist Automating Therapeutic Target Discovery. bioRxiv 2025.

- Mukherjee, A.; Kumar, P.; Yang, B.; Chandran, N.; Gupta, D. Privacy Preserving Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning in Supply Chains. ArXiv 2023, abs/2312.05686.

- Shanmugarasa, Y.; Ding, M.; Chamikara, M.; Rakotoarivelo, T. SoK: The Privacy Paradox of Large Language Models: Advancements, Privacy Risks, and Mitigation. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.12699.

- Li, Y.; Choi, D.; Chung, J.; Kushman, N.; Schrittwieser, J.; Leblond, R.; Eccles, T.; Keeling, J.; Gimeno, F.; Dal Lago, A.; et al. Competition-level code generation with AlphaCode. Science 2022, 378, 1092–1097.

- Pan, R.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C. CodeCoR: An LLM-Based Self-Reflective Multi-Agent Framework for Code Generation. ArXiv 2025, abs/2501.07811.

- Lin, Z.; Shen, Y.; Cai, Q.; Sun, H.; Zhou, J.; Xiao, M. AutoP2C: An LLM-Based Agent Framework for Code Repository Generation from Multimodal Content in Academic Papers. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.20115.

- Dobbins, N.J.; Xiong, C.; Lan, K.; Yetisgen-Yildiz, M. Large Language Model-Based Agents for Automated Research Reproducibility: An Exploratory Study in Alzheimer’s Disease. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.23852.

- Ju, T.; Wang, B.; Fei, H.; Lee, M.L.; Hsu, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, P.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Investigating the Adaptive Robustness with Knowledge Conflicts in LLM-based Multi-Agent Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2502.15153.

- Azadeh, R. Advances in Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning: Persistent Autonomy and Robot Learning Lab Report 2024. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.21088 2024.

- Swanson, K.; Wu, W.; Bulaong, N.L.; Pak, J.E.; Zou, J. The Virtual Lab: AI Agents Design New SARS-CoV-2 Nanobodies with Experimental Validation. bioRxiv 2024. Preprint, . [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qian, C.; Xia, Y.; Shi, R.; Dang, Y.; Xie, Z.; You, Z.; Chen, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, W.; et al. Cross-Task Experiential Learning on LLM-based Multi-Agent Collaboration. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.23187.

- Szymanski, N.; Rendy, B.; Fei, Y.; Kumar, R.E.; He, T.; Milsted, D.; McDermott, M.J.; Gallant, M.C.; Cubuk, E.D.; Merchant, A.; et al. An autonomous laboratory for the accelerated synthesis of novel materials. Nature 2023, 624, 86 – 91.

- Jin, Z.; Wu, Q.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Xu, W.; Liao, Y.; Feng, L.; Hu, M.; Li, B. TopoMAS: Large Language Model Driven Topological Materials Multiagent System. arXiv preprint 2025, [2507.04053].

- Wölflein, G.; Ferber, D.; Truhn, D.; Arandjelovi’c, O.; Kather, J. LLM Agents Making Agent Tools. ArXiv 2025, abs/2502.11705.

- Seo, S.; Kim, J.; Shin, M.; Suh, B. LLMDR: LLM-Driven Deadlock Detection and Resolution in Multi-Agent Pathfinding. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.00717.

- de Witt, C.S. Open Challenges in Multi-Agent Security: Towards Secure Systems of Interacting AI Agents. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.02077.

- Sun, L.; Yang, Y.; Duan, Q.; Shi, Y.; Lyu, C.; Chang, Y.C.; Lin, C.T.; Shen, Y. Multi-Agent Coordination across Diverse Applications: A Survey, 2025, [arXiv:cs.MA/2502.14743].

- Kusne, A.G.; McDannald, A. Scalable multi-agent lab framework for lab optimization. Matter 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Sarkar, M.; Lonappan, A.I.; Íñigo Zubeldia.; Villanueva-Domingo, P.; Casas, S.; Fidler, C.; Amancharla, C.; Tiwari, U.; Bayer, A.; et al. Open Source Planning & Control System with Language Agents for Autonomous Scientific Discovery. arXiv preprint 2025, [2507.07257].

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Zheng, T.; Song, M. Parallelized Planning-Acting for Efficient LLM-based Multi-Agent Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.03505.

- Park, C.; Han, S.; Guo, X.; Ozdaglar, A.; Zhang, K.; Kim, J.K. MAPoRL: Multi-Agent Post-Co-Training for Collaborative Large Language Models with Reinforcement Learning. ArXiv 2025, abs/2502.18439.

- Lan, T.; Zhang, W.; Lyu, C.; Li, S.; Xu, C.; Huang, H.; Lin, D.; Mao, X.L.; Chen, K. Training Language Models to Critique With Multi-agent Feedback. ArXiv 2024, abs/2410.15287.

- Du, Z.; Qian, C.; Liu, W.; Xie, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, R.; Dang, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, C.; Tian, Y.; et al. Multi-Agent Collaboration via Cross-Team Orchestration. arXiv 2024, [arXiv:cs.CL/2406.08979]. Accepted to Findings of ACL 2025.

- Zhu, K.; Du, H.; Hong, Z.; Yang, X.; Guo, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qian, C.; Tang, X.; Ji, H.; et al. MultiAgentBench: Evaluating the Collaboration and Competition of LLM agents. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.01935.

- Soldatova, L.N.; Rzhetsky, A. Representation of research hypotheses. Journal of Biomedical Semantics 2011, 2, S9 – S9.

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, K.; Fang, M. Deep Research Agents: A Systematic Examination And Roadmap. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.18096 2025.

- Tran, K.T.; Dao, D.; Nguyen, M.D.; Pham, Q.V.; O’Sullivan, B.; Nguyen, H.D. Multi-Agent Collaboration Mechanisms: A Survey of LLMs. ArXiv 2025, abs/2501.06322.

- Bandi, C.; Harrasse, A. Adversarial Multi-Agent Evaluation of Large Language Models through Iterative Debates. ArXiv 2024, abs/2410.04663.

- Pu, Z.; Ma, H.; Hu, T.; Chen, M.; Liu, B.; Liang, Y.; Ai, X. Coevolving with the Other You: Fine-Tuning LLM with Sequential Cooperative Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. ArXiv 2024, abs/2410.06101.

- Chun, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Ahmed, I. Is Multi-Agent Debate (MAD) the Silver Bullet? An Empirical Analysis of MAD in Code Summarization and Translation. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.12029.

- Pu, Y.; Lin, T.; Chen, H. PiFlow: Principle-aware Scientific Discovery with Multi-Agent Collaboration. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.15047.

- Song, K.; Trotter, A.; Chen, J.Y. LLM Agent Swarm for Hypothesis-Driven Drug Discovery. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.17967.

- Koscher, B.A.; Canty, R.B.; McDonald, M.A.; Greenman, K.P.; McGill, C.J.; Bilodeau, C.L.; Jin, W.; Wu, H.; Vermeire, F.H.; Jin, B.; et al. Autonomous, multiproperty-driven molecular discovery: From predictions to measurements and back. Science 2023, 382.

- Chen, X.; Che, M.; et al. An automated construction method of 3D knowledge graph based on multi-agent systems in virtual geographic scene. International Journal of Digital Earth 2024, 17, 2449185. [CrossRef]

- Al-Neaimi, A.; Qatawneh, S.; Saiyd, N.A. Conducting Verification And Validation Of Multi- Agent Systems, 2012, [arXiv:cs.SE/1210.3640].

- Nguyen, T.P.; Razniewski, S.; Weikum, G. Towards Robust Fact-Checking: A Multi-Agent System with Advanced Evidence Retrieval. arXiv preprint 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2506.17878].

- Ferrag, M.A.; Tihanyi, N.; Hamouda, D.; Maglaras, L. From Prompt Injections to Protocol Exploits: Threats in LLM-Powered AI Agents Workflows. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.23260 2025.

- Wang, H.; Du, X.; Yu, W.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, K.; Chu, Z.; Yan, L.; Guan, Y. Learning to break: Knowledge-enhanced reasoning in multi-agent debate system. Neurocomputing 2023, 618, 129063.

- Li, Z.; Chang, Y.; Le, X. Simulating Expert Discussions with Multi-agent for Enhanced Scientific Problem Solving. Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Scholarly Document Processing (SDP 2024) 2024.

- Pantiukhin, D.; Shapkin, B.; Kuznetsov, I.; Jost, A.A.; Koldunov, N. Accelerating Earth Science Discovery via Multi-Agent LLM Systems. ArXiv 2025, abs/2503.05854.

- Solovev, G.V.; Zhidkovskaya, A.B.; Orlova, A.; Vepreva, A.; Tonkii, I.; Golovinskii, R.; Gubina, N.; Chistiakov, D.; Aliev, T.A.; Poddiakov, I.; et al. Towards LLM-Driven Multi-Agent Pipeline for Drug Discovery: Neurodegenerative Diseases Case Study. In Proceedings of the OpenReview Preprint, 2024.

- Sami, M.A.; Rasheed, Z.; Kemell, K.; Waseem, M.; Kilamo, T.; Saari, M.; Nguyen-Duc, A.; Systä, K.; Abrahamsson, P. System for systematic literature review using multiple AI agents: Concept and an empirical evaluation. CoRR 2024, abs/2403.08399, [2403.08399]. [CrossRef]

- Mankowitz, D.J.; Michi, A.; Zhernov, A.; Gelada, M.; Selvi, M.; Paduraru, C.; Leurent, E.; Iqbal, S.; Lespiau, J.B.; Ahern, A.; et al. Faster sorting algorithms discovered using deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2023, 618, 257–263.

- Trinh, T.H.; Wu, Y.; Le, Q.V.; He, H.; Luong, T. Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations. Nature 2024, 625, 476–482.

- Fawzi, A.; Balog, M.; Huang, A.; Hubert, T.; Romera-Paredes, B.; Barekatain, M.; Novikov, A.; Ruiz, F.J.; Schrittwieser, J.; Swirszcz, G.; et al. Discovering faster matrix multiplication algorithms with reinforcement learning. Nature 2022, 610, 47–53.

- Vinyals, O.; Babuschkin, I.; Czarnecki, W.M.; Mathieu, M.; Dudzik, A.; Chung, J.; Choi, D.H.; Powell, R.; Ewalds, T.; Georgiev, P.; et al. Grandmaster level in StarCraft II using multi-agent reinforcement learning. Nature 2019, 575, 350–354.

- Silver, D.; Schrittwieser, J.; Simonyan, K.; Antonoglou, I.; Huang, A.; Guez, A.; Hubert, T.; Baker, L.; Lai, M.; Bolton, A.; et al. Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge. Nature 2017, 550, 354–359. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Du, X.; Yu, W.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, K.; Chu, Z.; Yan, L.; Guan, Y. Learning to break: Knowledge-enhanced reasoning in multi-agent debate system. Neurocomputing 2023, 618, 129063.

- Xiang, Y.; Yan, H.; Ouyang, S.; Gui, L.; He, Y. SciReplicate-Bench: Benchmarking LLMs in Agent-driven Algorithmic Reproduction from Research Papers. ArXiv 2025, abs/2504.00255.

- Smith, J.; et al. Leveraging Multi-AI Agents for Cross-Domain Knowledge Discovery. arXiv preprint 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2404.08511].

- Su, H.; Chen, R.; Tang, S.; Yin, Z.; Zheng, X.; Li, J.; Qi, B.; Wu, Q.; Li, H.; Ouyang, W.; et al. Many Heads Are Better Than One: Improved Scientific Idea Generation by A LLM-Based Multi-Agent System, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2410.09403].

- Li, A.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, W.; Ding, J.; Liu, J. Agent-Oriented Planning in Multi-Agent Systems. arXiv preprint 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2410.02189].

- Fukuda, M.; Gordon, C.; Mert, U.; Sell, M. MASS: A Parallelizing Library for Multi-Agent Spatial Simulation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSIM Conference on Principles of Advanced Discrete Simulation (PADS). ACM, 2013, pp. 161–170. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, K.; Li, H.; Zhang, T.J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qu, P.; He, J.; Chen, J.; Yuan, Y.J.; Han, J.; et al. SeePhys: Does Seeing Help Thinking? – Benchmarking Vision-Based Physics Reasoning, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2505.19099].

- Tang, K.; Wu, A.; Lu, Y.; Sun, G. Collaborative Editable Model. ArXiv 2025, abs/2506.14146.

- Chen, N.; HuiKai, A.L.; Wu, J.; Hou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; He, B. XtraGPT: LLMs for Human-AI Collaboration on Controllable Academic Paper Revision. ArXiv 2025, abs/2505.11336.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).