Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Text Mining

- Structured Data: These data are standardized as tables of multiple rows and columns. This makes them easier to store and process. Structured data can include entries such as name, address, and phone number.

- Unstructured Data: These data do not have a predefined and specific format. This data can include text from social media, product reviews, or video and audio files.

- Semi-structured Data: As the name suggests, this data combines structured and unstructured data. Examples of semi-structured data include XML, JSON, and HTML files.

2.1. Text Data Augmentation

2.1.1. Machine Translation Quality

BLEU Score

- N is the maximum n-gram length considered (commonly ).

- is the weight assigned to the precision score of n-grams of order n (typically uniform weights, ).

- is the modified precision for n-grams of order n.

- BP is the brevity penalty that penalizes overly short translations.

- represents the set of all candidate translations in the test corpus

- is computed as:where are the reference translations for the candidate C

- counts each n-gram occurrence in the candidate translation

- c is the total length (in words) of the candidate translations.

- r is the effective reference length, defined as the sum of the lengths of the reference translations closest to each candidate sentence’s length.

2.1.2. Text Generation Quality

- Novelty:Novelty and Diversity are distinct. Novelty covers the difference of the produced text from the training set, while Diversity covers the difference of the produced text from other produced texts. A model can be diverse but not novel. These two criteria are listed below [39]:

-

Diversity: BLEU [38] and Self-BLEU [40] are common metrics for quality and diversity evaluation, respectively:Calculate BLEU score for every generated sentence, and define the average BLEU score to be the Self-BLEU of the document.Discriminative BLEU [41]: For tasks with inherently diverse outputs, such as conversational response generation, where there is a wide range of plausible and acceptable responses, BLEU is introduced as an enhanced version of the traditional BLEU score. Unlike standard BLEU, BLEU incorporates human judgments about the quality of reference texts, making it more discriminative. It rewards matches with high-quality references and penalizes matches with low-quality ones, thereby better aligning with human evaluations. This makes BLEU particularly suitable for tasks like conversational response generation, where the space of valid outputs is vast and subjective. The BLEU score for a corpus is computed as:where BP is the brevity penalty, and is the modified n-gram precision for n-grams of order n. The modified n-gram precision is defined as:where:

- −

- i is index over the test set, and j is index over the set of references for the i-th input message.

- −

- is the minimum number of occurrences of n-gram g in the hypothesis and reference .

- −

- is the human-assigned weight for reference .

-

Fluency: This is a subjective and multidimensional concept that can be related to various criteria, such as readability, clarity, and naturalness of the produced text. The context, purpose and audience of the text production task influence fluency. For example, a fluent text for a news article may differ from a fluent text for a children’s story. The text production fluency depends on the desired program. In technical writing, clarity and precision can be essential. The following evaluation criteria can be used to evaluate fluency [42].SLOR:The Syntactic Log Odds Ratio (SLOR) is a metric designed for the evaluation of fluency in natural language generation (NLG) outputs. Its primary purpose is to assess the fluency of generated sentences without relying on reference sentences, which can be particularly useful in scenarios where references are unavailable or impractical to obtain. The SLOR metric is defined mathematically as follows [43]:In this equation, S represents the sentence being evaluated, is the probability assigned to the sentence by a language model (LM), and is the unigram probability of the sentence, calculated as the product of the probabilities of each individual token in the sentence. The normalization by , the length of the sentence, ensures that the metric accounts for variations in sentence length, allowing for a fair comparison between sentences of different sizes. By leveraging the probabilities from a trained language model, SLOR provides a more nuanced evaluation of fluency, making it a valuable tool for researchers and practitioners in the field of natural language processing.Perplexity(PPL),wang2022perplexity: Perplexity (PPL) is one of the most common criteria for evaluating language models. PPL is a metric used to evaluate the fluency and quality of generated text by language models. It is derived from cross-entropy. Mathematically, the cross-entropy H for a sequence of tokens can be expressed as:where is the predicted probability of the i-th token given the previous tokens. PPL is then defined as the exponentiation of the average cross-entropy:where s is the input sentence and m is the number of tokens in the sequence. A lower PPL value indicates better fluency and quality of the text generated by the model.

-

Sentiment Consistency: In the context of text generation, maintaining sentiment consistency is crucial for ensuring that the generated text aligns with the expected emotional tone of the input prompts. In [45], two primary metrics are introduced to evaluate sentiment consistency in generated continuations: SENTSTD and SENTDIFF. These metrics help assess how well the sentiment of the generated text corresponds to the ground truth.

- SENTSTD (Sentiment Standard Deviation),feng2020genaug: This metric measures the average standard deviation of sentiment scores for each batch of generated continuations, concatenated with their respective input prompts. By calculating the standard deviation across all test examples, a lower SENTSTD value indicates greater consistency in sentiment among the generated continuations. This suggests that the generated texts exhibit a more stable emotional tone.

- SENTDIFF (Sentiment Difference),feng2020genaug: This metric evaluates the average difference in sentiment scores between each batch of continuations and their corresponding ground-truth reviews. By averaging these differences across all test examples, a lower SENTDIFF value indicates that the sentiment of the generated continuations aligns more closely with the ground-truth reviews. This metric is essential for assessing the fidelity of the generated text to the expected sentiment.

-

Semantic content preservation,zhang2019bertscore: This evaluation metric is designed to assess the semantic equivalence between generated text and reference text. Unlike traditional metrics that rely on surface form similarity, this metric leverages contextual embeddings to evaluate how well the meaning of the content is preserved in the generated output. The BERTSCORE metric computes the similarity between tokens in the candidate sentence and those in the reference sentence using cosine similarity of their contextual embeddings. The formula for computing the recall, precision, and F1 scores is given as follows:where:

- −

- x is the reference sentence tokenized into k tokens .

- −

- is the candidate sentence tokenized into l tokens .

- −

- and represent the contextual embeddings of tokens and , respectively.

- −

- is the cosine similarity between vectors a and b.

This approach allows for a more nuanced evaluation of text generation, focusing on the preservation of meaning rather than mere lexical overlap, thereby addressing common pitfalls in traditional n-gram based metrics. To enhance this evaluation, Inverse Document Frequency (IDF) weighting is incorporated, which emphasizes the importance of rare and informative tokens. The Recall metric with IDF weighting is defined as follows:where:- −

- is the IDF score of token , where M is the total number of reference sentences, and is the number of sentences containing .

2.1.3. Character n-gram matches

-

Character n-gram F-score (CHRF),popovic2017chrf++: This evaluation metric assesses the quality of machine translation outputs by leveraging character n-grams. CHRF correlates well with human assessments, particularly for morphologically rich languages. It calculates precision and recall based on character n-grams, making it language-independent and robust against tokenization issues. The general formula for the n-gram based F-score is given by:where:

- −

- is the character n-gram precision, calculated as the average precision across all n-grams from to N.

- −

- is the character n-gram recall, representing the average recall across all n-grams from to N.

- −

- is a parameter that assigns times more weight to recall than to precision, with a typical value of 2 being optimal.

The CHRF score is computed by averaging the precision and recall across n-grams of lengths from 1 to N, where N is typically set to 6 for character n-grams. - CHRF+: CHRF+ enhances the original CHRF metric by incorporating word unigrams alongside character n-grams. This integration aims to improve correlation with direct human assessments by capturing both surface-level and semantic information. The precision and recall for CHRF+ ( and ) are calculated as the combined metrics of both character and word n-grams, averaged across all n-gram lengths.

- CHRF++: CHRF++ further refines the CHRF+ metric by optimizing the combination of character and word n-grams, particularly by incorporating word unigrams and bigrams. This variant enhances correlation with direct human assessments by capturing more contextual information from the text. The precision and recall for CHRF++ ( and ) are computed with enhanced weighting strategies for character and word n-grams, allowing for a more nuanced evaluation.

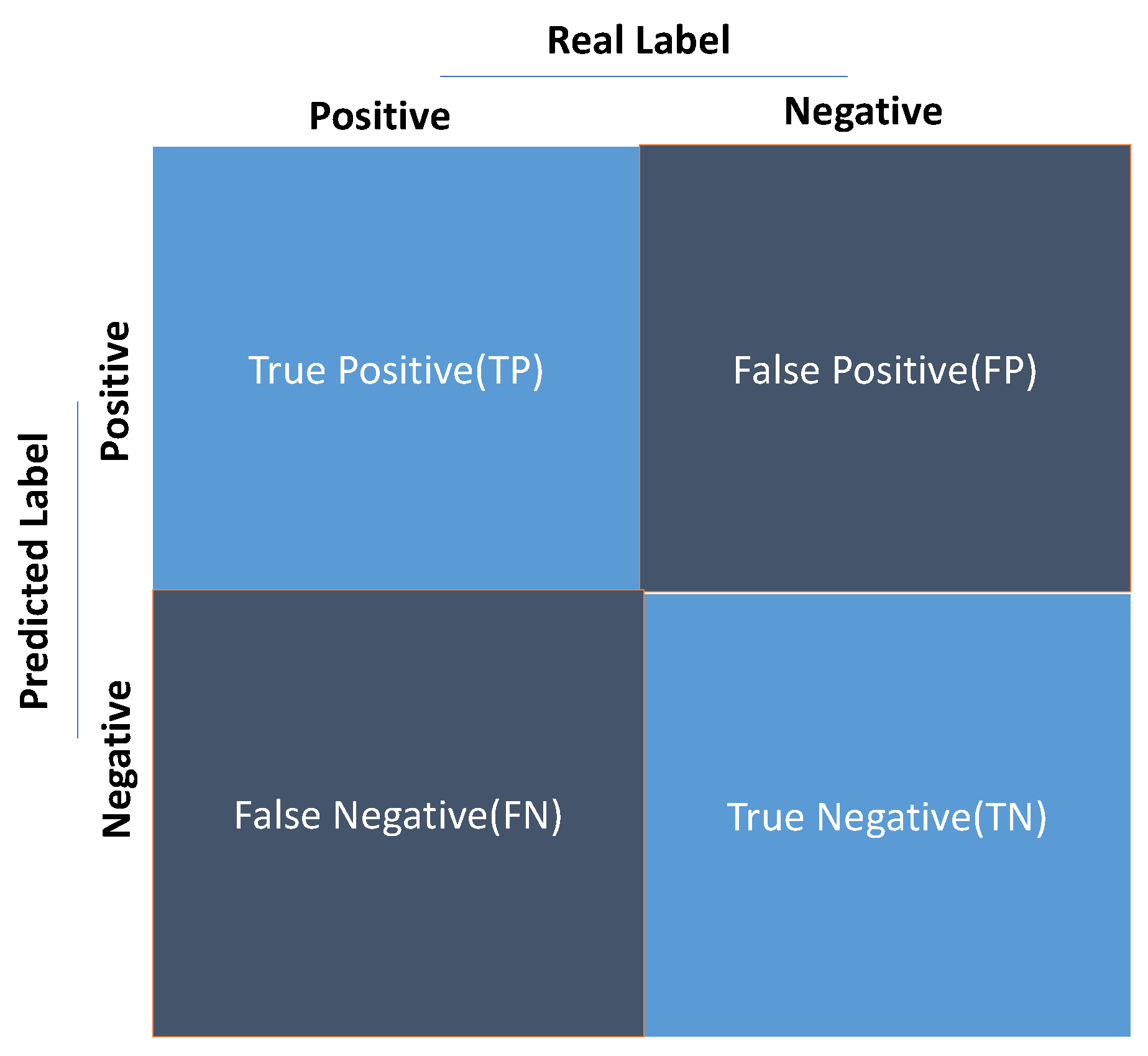

2.1.4. Prediction quality for classification

- Error inspection of each class.

- Setting software parameters such as detection threshold.

- Comparing software versions [50].

2.2. Dataset Correlations

- : The difference between the ranks of the two variables for each observation.

- n: The number of paired observations.

- is the dot product of the vectors and .

- is the Euclidean norm (magnitude) of vector , calculated as .

- is the Euclidean norm (magnitude) of vector , calculated as .

- is the angle between the two vectors.

2.3. Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) Performance

2.4. Training

2.5. Discriminator Metrics

2.6. Agreement Metrics

2.7. Metrics for Evaluating Recommendation Systems

2.7.1. Predicting User Ratings

| Metric | Formula and Description |

|---|---|

| Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) |

|

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) |

|

| Normalized RMSE (NRMSE) |

|

| Normalized MAE (NMAE) |

|

2.7.2. Ranking-Based Metrics

- U is the total number of users,

- K is the cutoff rank,

- is an indicator function that equals 1 if the item at rank i is relevant to user u, and 0 otherwise,

- i is the rank position of the item.

2.7.3. Coverage

Catalogue Coverage

- : The set of items recommended to users.

- : The set of all available items in the catalogue.

Weighted Catalogue Coverage

- : The set of items recommended to users.

- : The set of items considered useful to users.

Prediction Coverage

- : The set of users for whom predictions can be made.

- : The set of all users in the system.

Weighted Prediction Coverage

- : The set of users for whom predictions can be made.

- : The set of all users in the system.

- : A function representing the usefulness of the recommendations for a specific user.

2.7.4. Diversity

2.7.4.1. Diversity

- : Items in the recommendation list.

- : A similarity metric between items and .

- n: The total number of items in the recommendation list.

Similarity

- t: The target query.

- c: The item being compared.

- : The weight assigned to the i-th feature.

- : A similarity heuristic between the i-th feature of t and c.

Quality

- : The similarity of item c to the target query t.

- : The diversity of c relative to the items in R.

Relative Diversity

- c: The new item being evaluated.

- R: The set of items already selected in the recommendation list.

- : The similarity between the new item c and an item in R.

- m: The number of items in R.

3. Image Mining

3.1. Evaluation Metrics for 3D Image Segmentation

3.1.1. Spatial Overlap Based Me3trics

- Basic cardinalities:

- Generalization to fuzzy segmentations:

- Calculation of overlap based metrics:

- Overlap measures for multiple labels:

3.1.2. Volume Based Metrics

3.1.3. Pair Counting Based Metrics

- Basic cardinalities

- Generalization to fuzzy segmentations:

- Calculation of pair-counting based metrics:

3.1.4. Information Theoretic Based Metrics

3.1.5. Probabilistic Metrics

- Interclass Correlation (ICC):

- Probabilistic Distance (PBD):

- ROC curve (Receiver Operating Characteristic)

3.1.6. Spatial Distance Based Metrics

- Distance between crisp volumes:

- Average Hausdorff Distance (AVD):

- Mahalanobis Distance (MHD):

- Extending the distances to fuzzy volumes

3.1.7. Multiple Definition of Met3rics in the Literature

3.2. Evaluation Metrics for Image Segmentation

3.2.1. Error Types of Image Segmentation

- CR (Correct Region):

- MD (Miss Detection):

- FA (False Alarm):

- BR (Background Region):

- Perfect segmentation:

- Completely incorrect segmentation:

- Isolated false alarm

- Isolated missed detection:

- Partial false alarm /miss detection:

- Over segmentation

- Under segmentation

3.2.2. Evaluation Metrics

- Pixel-based metric:

- Object-based metric:Martin’s methodwhere

- Object-based metric: Polak’s method:

3.2.3. Error Measures

| Types | Pixel based | Martin’s metrics | Polak’s metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect segmentation | √ | √ | √ |

| Completely inaccurate segmentation | √ | × | × |

| Isolated false alarm | √ | × | × |

| Isolated missed detection | √ | × | × |

| Partial false alarm/ missed detection | √ | × | □ |

| Over-segmentation | √ | × | √ |

| Under-segmentation | √ | × | √ |

4. Evaluating Metrics for Clustering Algorithms

- Coverage: ,

- Disjointness: .

- The cluster centroid (mean vector) for :

- The dataset centroid (global mean):

4.1. Cluster Validity Indices (CVIs)

| Index Name | Description/Definition | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Dunn Index (D↑) | Measures the ratio of the minimum inter-cluster distance to the maximum intra-cluster distance. Higher values indicate better clustering. | [83] |

| Calinski-Harabasz Index (CH↑) | Ratio of the sum of between-cluster dispersion to within-cluster dispersion. Higher values indicate better clustering. | [84] |

| Davies-Bouldin Index (DB↓) | Measures the average similarity between each cluster and the cluster most similar to it. Lower values indicate better clustering. | [85] |

| Silhouette Index (Sil↑) | Combines cohesion (average intra-cluster distance) and separation (average nearest-cluster distance) into a single measure. Values range from -1 to 1, where higher values indicate better clustering. | [86] |

| Gamma Index (G↓) | Measures the correlation between the distances of pairs of points and their clustering assignments. Higher values indicate better clustering. | [87] |

| C Index (CI↓) | Normalized measure of intra-cluster distances compared to minimum and maximum possible distances. Lower values indicate better clustering. | [88] |

| S_Dbw Index (SDbw↓) | Combines intra-cluster variance and inter-cluster density to evaluate clustering quality. Lower values indicate better clustering. | [89] |

| CS Index (CS↓) | Estimates cohesion by cluster diameters and separation by the nearest neighbor distance. Lower values indicate better clustering. | [90] |

| Symmetry Index (Sym↑) | Measures the symmetry of clusters around their centroids using the Point Symmetry Distance. Lower values indicate better clustering. | [91] |

| COP Index (COP↓) | Combines intra-cluster cohesion (distance to centroid) and inter-cluster separation (furthest neighbor distance). Lower values indicate better clustering. | [92] |

| Negentropy Increment (NI↓) | Based on entropy, measures the increase in negentropy when clustering is applied. Higher values indicate better clustering. | [93] |

| Score Function (SF↑) | Combines between-cluster dispersion and within-cluster dispersion using a weighted exponential function. Higher values indicate better clustering. | [94] |

| Generalized Dunn Index (gD31, gD41, gD51, gD33, gD43, gD53) | Variants of the Dunn index using different measures for cohesion and separation. Higher values indicate better clustering. | [95] |

| Graph theory based Dunn and Davies– Bouldin variations |

Dunn index variants that use graph-based measures (Minimum Spanning Tree, Relative Neighborhood Graph, Gabriel Graph) for cohesion. | [96] |

| Point Symmetry-Based Indices (SymDB↓, SymD↑, Sym33↑) | Variants of the Davies-Bouldin, Dunn, and Generalized Dunn indices using Point Symmetry Distance for cohesion. Lower values indicate better clustering. | [97] |

| Davies–Bouldinn* (DB*↓) | A modification of the Davies-Bouldin index. | [98] |

| SV Index (SV↑) | Combines separation (nearest neighbor distance) and cohesion (distance of border points to centroid). Lower values indicate better clustering. | [99] |

| OS Index (OS↑) | Combines a more complex separation estimator with cohesion (distance of border points to centroid). Lower values indicate better clustering. | [99] |

4.2. Internal Validation Methods

4.2.1. Metrics for Partitional Clustering Algorithms

- Sum of Squared Errors (SSE): Measures the compactness of clusters by calculating the sum of squared distances between each data point and its cluster centroid. Lower SSE values indicate better clustering.

- Silhouette Coefficient: Combines cohesion and separation into a single metric. It compares the average distance of a point to other points in its cluster (cohesion) with the average distance to points in the nearest neighboring cluster (separation). Values range from -1 to 1, where higher values indicate better clustering.

- Calinski-Harabasz Index (CH): Also known as the variance ratio criterion, this index measures the ratio of between-cluster dispersion to within-cluster dispersion. Higher CH values indicate better-defined clusters.

- Dunn Index: Evaluates the ratio of the smallest distance between clusters (separation) to the largest intra-cluster distance (cohesion). A higher Dunn Index signifies better clustering.

- Xie-Beni Index: Originally designed for fuzzy clustering, this metric estimates the compactness and separation of clusters. It is also applicable to hard clustering methods.

4.2.2. Metrics for Hierarchical Clustering Algorithms

- Cophenetic Correlation Coefficient (CPCC): Measures how faithfully the dendrogram preserves the pairwise distances between data points. High CPCC values indicate that the hierarchical clustering algorithm has captured the underlying structure of the data.

- Hubert Statistic: Similar to CPCC, this metric evaluates the concordance between the proximity matrix and the cophenetic matrix derived from the dendrogram. Higher Hubert values suggest better clustering.

- Proximity Matrix Correlation: Compares the actual proximity matrix to an idealized block-diagonal matrix based on the clustering results. High correlation indicates well-formed clusters.

4.2.3. Innovative Perspective on Internal Validation

4.2.4. Conclusion

4.2.5. Partitional Methods

- cohesion:Cohesion evaluates how close the elements of a cluster are to each other. This index is defined as follows [100]:

- Separation:eparation measures the level of separation between clusters. This index is defined as follows [100]:

- Sum of Squared Errors Within Cluster:It should be noted that the coherence metric defined above is equivalent to the cluster Sum of Squared Errors Within Cluster(SSW). In general, this metric can be defined as follows [101]:

- Maximize distance between clusters: This metric maximizes the distance between clusters and is defined as follows:

- Calisnki-Harabasz coefficient(CH): The CH, makes the final decision based on the measure of intra-cluster dispersion and inter-cluster dispersion. The goal is to choose the number of clusters that maximize CH. This criterion is known as the variance ratio criterion and is defined as follows [84]:

- Dunn index: This index has been reviewed before and can also be defined as follows:

- Xie-Beni score:This index is ratio-based, and its numerator estimates the level of data density in the same cluster, and its denominator estimates the level of separation of data from different clusters. It is designed for fuzzy clustering, but it can also be used for hard clustering. This index can be defined as follows [102]:

- Ball-Hall index: This index is a dispersion measure that performs clustering based on the quadratic distance of the cluster points concerning their center and is defined as follows [103]:

- Hartigan index: This index performs clustering based on the logarithmic relationship between the sum of squares within the cluster and the sum of squares between the clusters and is defined as follows [104]:

- Xu coefficient: This coefficient considers the clustering of dimensions D of data, the number N of data samples, and the sum of squared errors of from M clusters [105]:

4.2.6. Hierarchical Methods

- Cophenetic Correlation Coefficient (CPCC): A hierarchical clustering algorithm is used to evaluate the results. This correlation coefficient was proposed as the correlation between the cophenetic matrix , containing cophenetic distances, and the proximity matrix P, containing similarities. This correlation coefficient is defined as [107].

- Hubert Statistic: Let and be the number of congruent and discordant pairs, respectively. This index is defined as [100]:

4.3. External Validation Met3hods

4.3.1. Matching Sets

- Precision: Counts the true positives.

- Recall: Calculates the percentage of elements that are correctly included in a cluster:

- F-Measure: combines precision and recall in a single metric.

-

Purity: It is used to evaluate whether each cluster contains only instances of the same class.Where , and

4.3.2. Peer-to-Peer Correlation

- Jaccard coefficient:

- Rand coefficient:

- Folkes and Mallows coefficient:

- Hubert statistical coefficient:

4.3.3. Measures Based on Information Theory

- Entropy:

- Mutual information:where ,, and .

5. Signal Mining

5.1. Similarity and Distance Met3rics

5.1.1. Euclidean Distance (ED)

5.1.2. Pearson Correlation Coefficient Distance (PCCD)

5.1.3. Symmetric Kullback–Leibler Divergence (SKLD)

5.1.4. Hellinger Distance (HD)

5.1.5. Bhattacharyya Distance (BD)

5.1.6. Minkowski

- : city block distance, or Manhattan distance.

- : In binary data, Hamming distance.

- : well-known Euclidean distance.

5.1.7. Entropy

5.1.8. Kullback-Leibler

5.1.9. Angle

5.1.10. Itakura-Saito

5.1.11. Dice, Cosine, and Jaccard Coefficient [Reff ]

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions: First Author

References

- Chowdhary, K. Natural language processing. Fundamentals of artificial intelligence 2020, pp. 603–649.

- Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Deveci, M.; Parmar, M. A review of convolutional neural networks in computer vision. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhavalkar, R.; Hori, T.; Sainath, T.N.; Schlüter, R.; Watanabe, S. End-to-end speech recognition: A survey. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing 2023, 32, 325–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Dutta, M. A systematic review and research perspective on recommender systems. Journal of Big Data 2022, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Nia, M.F.; Asgarian, S.; Danesh, K.; Irankhah, E.; Lonbar, A.G.; Sharifi, A. Comparative analysis of segment anything model and u-net for breast tumor detection in ultrasound and mammography images. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.12510 2023.

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. Deep learning on medical image analysis. CAAI Transactions on Intelligence Technology 2025, 10, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, G.; Lostanlen, V.; Yang, Y.H.; Müller, M. Model-Based Deep Learning for Music Information Research: Leveraging diverse knowledge sources to enhance explainability, controllability, and resource efficiency [Special Issue On Model-Based and Data-Driven Audio Signal Processing]. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2025, 41, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nia, M.F. Explore Cross-Codec Quality-Rate Convex Hulls Relation for Adaptive Streaming. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.09044 2024.

- Kessler, R.; Béchet, N. Deep Learning and Natural Language Processing in the Field of Construction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.07911 2025.

- Farhadi Nia, M.; Ahmadi, M.; Irankhah, E. Transforming dental diagnostics with artificial intelligence: advanced integration of ChatGPT and large language models for patient care. Frontiers in Dental Medicine 2025, 5, 1456208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norcéide, F.S.; Aoki, E.; Tran, V.; Nia, M.F.; Thompson, C.; Chandra, K. Positional Tracking of Physical Objects in an Augmented Reality Environment Using Neuromorphic Vision Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1031–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Mhamed, M.; Zhang, Z.; Hua, W.; Yang, L.; Huang, M.; Li, X.; Bai, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, M. Apple varieties and growth prediction with time series classification based on deep learning to impact the harvesting decisions. Computers in Industry 2025, 164, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordani, M.; Bagheritabar, M.; Ahmadianfar, I.; Samadi-Koucheksaraee, A. Forecasting water quality indices using generalized ridge model, regularized weighted kernel ridge model, and optimized multivariate variational mode decomposition. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 16313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordani, M.; Nikoo, M.R.; Fooladi, M.; Ahmadianfar, I.; Nazari, R.; Gandomi, A.H. Improving long-term flood forecasting accuracy using ensemble deep learning models and an attention mechanism. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering 2024, 29, 04024042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nia, M.F.; Callen, G.E.; An, J.; Chandra, K.; Thompson, C.; Wolkowicz, K.; Denis, M. Experiential Learning for Interdisciplinary Education on Vestibular System Models. In Proceedings of the ASEE annual conference exposition; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Arendt, P.; Huang, H.Z. Toward a better understanding of model validation metrics 2011.

- Chatfield, C. Model uncertainty, data mining and statistical inference. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society 1995, 158, 419–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K. Research evaluation metrics; Vol. 4, UNESCO Publishing, 2015.

- Caldiera, V.R.B.G.; Rombach, H.D. The goal question metric approach. Encyclopedia of software engineering 1994, pp. 528–532.

- Ampel, B.; Yang, C.H.; Hu, J.; Chen, H. Large language models for conducting advanced text Analytics Information Systems Research. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshiri, A.; Ryu, K.R.; Park, J.Y. Text mining and natural language processing in construction. Automation in Construction 2024, 158, 105200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, V.B.; Mol, S.T.; Berkers, H.A.; Kismihók, G.; Den Hartog, D.N. Text mining in organizational research. Organizational research methods 2018, 21, 733–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfoq, M.S.; Albeer, R.A.; Abd, E.H.; et al. A Review Of Text Mining Techniques: Trends, and Applications In Various Domains. Iraqi Journal For Computer Science and Mathematics 2024, 5, 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Cui, A.P.; Han, S. Linking big data analytical intelligence to customer relationship management performance. Industrial Marketing Management 2020, 91, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheja, S.; Munjal, G. Text mining for secure cyber space. Intelligent Data Analytics for Terror Threat Prediction: Architectures, Methodologies, Techniques and Applications 2021, pp. 95–118.

- Ceballos Delgado, A.A.; Glisson, W.; Shashidhar, N.; Mcdonald, J.; Grispos, G.; Benton, R. Deception detection using machine learning 2021.

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: A pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhasuran, B. Combining Literature Mining and Machine Learning for Predicting Biomedical Discoveries. In Biomedical Text Mining; Springer, 2022; pp. 123–140.

- Martinelli, G.; Molfese, F.; Tedeschi, S.; Fernández-Castro, A.; Navigli, R. CNER: Concept and Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2024, pp. 8329–8344.

- Majumdar, A.; Ajay, A.; Zhang, X.; Putta, P.; Yenamandra, S.; Henaff, M.; Silwal, S.; Mcvay, P.; Maksymets, O.; Arnaud, S.; et al. Openeqa: Embodied question answering in the era of foundation models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 16488–16498.

- Kouris, P.; Alexandridis, G.; Stafylopatis, A. Text summarization based on semantic graphs: An abstract meaning representation graph-to-text deep learning approach. Journal of Big Data 2024, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.K.; Jeon, H.; Park, G.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, N.W.; Kim, J.; Seo, J. Natural language dataset generation framework for visualizations powered by large language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2024, pp. 1–22.

- Pérez, C.R. Re-thinking machine translation post-editing guidelines. The Journal of Specialised Translation 2024, pp. 26–47.

- Chan, K.; Yeung, P.s.; Chung, K.K.H. The effects of foreign language anxiety on English word reading among Chinese students at risk of English learning difficulties. Reading and Writing 2024, pp. 1–19.

- Zhu, Q.; Gao, L.; Qin, L. DFNet: Decoupled Fusion Network for Dialectal Speech Recognition. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, P.; Phalnikar, N.; Kurmi, D.; Tembhurne, J.; Sahare, P.; Diwan, T. OCR-MRD: Performance analysis of different optical character recognition engines for medical report digitization. International Journal of Information Technology 2024, 16, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadeus, M.; Castañeda, W.A.C. Evaluation Metrics for Text Data Augmentation in NLP. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.06766 2024.

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. Bleu: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 40th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2002, pp. 311–318.

- McCoy, R.T.; Smolensky, P.; Linzen, T.; Gao, J.; Celikyilmaz, A. How much do language models copy from their training data? evaluating linguistic novelty in text generation using raven. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2023, 11, 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Lu, S.; Zheng, L.; Guo, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y. Texygen. In Proceedings of the The 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval. ACM; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Galley, M.; Brockett, C.; Sordoni, A.; Ji, Y.; Auli, M.; Quirk, C.; Mitchell, M.; Gao, J.; Dolan, B. deltaBLEU: A discriminative metric for generation tasks with intrinsically diverse targets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1506.06863 2015.

- Morris, D.; Pennell, A.M.; Perney, J.; Trathen, W. Using subjective and objective measures to predict level of reading fluency at the end of first grade. Reading Psychology 2018, 39, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kann, K.; Rothe, S.; Filippova, K. Sentence-level fluency evaluation: References help, but can be spared! arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.08731 2018.

- Wang, Y.; Deng, J.; Sun, A.; Meng, X. Perplexity from plm is unreliable for evaluating text quality. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.05892 2022.

- Feng, S.Y.; Gangal, V.; Kang, D.; Mitamura, T.; Hovy, E. Genaug: Data augmentation for finetuning text generators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.01794 2020.

- Zhang, T.; Kishore, V.; Wu, F.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Artzi, Y. Bertscore: Evaluating text generation with bert. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.09675 2019.

- Popović, M. chrF++: Words helping character n-grams. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the second conference on machine translation, 2017, pp. 612–618.

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) is more informative than Cohen’s Kappa and Brier score in binary classification assessment. Ieee Access 2021, 9, 78368–78381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstinić, D.; Braović, M.; Šerić, L.; Božić-Štulić, D. Multi-label classifier performance evaluation with confusion matrix. Computer Science & Information Technology 2020, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Beauxis-Aussalet, E.; Hardman, L. Simplifying the visualization of confusion matrix. In Proceedings of the 26th Benelux conference on artificial intelligence (BNAIC); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ali Abd Al-Hameed, K. Spearman’s correlation coefficient in statistical analysis. International Journal of Nonlinear Analysis and Applications 2022, 13, 3249–3255. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, P.; Zhang, L.; Li, F. Learning similarity with cosine similarity ensemble. Information sciences 2015, 307, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Renals, S. Word error rate estimation for speech recognition: e-WER. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), 2018, pp. 20–24.

- Malik, M.; Malik, M.K.; Mehmood, K.; Makhdoom, I. Automatic speech recognition: A survey. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2021, 80, 9411–9457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.; Wookey, S. The real-world-weight cross-entropy loss function: Modeling the costs of mislabeling. IEEE access 2019, 8, 4806–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossin, M.; Sulaiman, M.N. A review on evaluation metrics for data classification evaluations. International journal of data mining & knowledge management process 2015, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerman, M.; Miller, A.R. Relationships between statistical measures of agreement: Sensitivity, specificity and kappa. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice 2008, 14, 930–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadla, H.K.; PVRDP, R. Machine learning based text classifier centered on TF-IDF vectoriser. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res 2020, 9, 583. [Google Scholar]

- Berbatova, M. Overview on NLP techniques for content-based recommender systems for books. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Student Research Workshop Associated with RANLP 2019, 2019, pp. 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Avazpour, I.; Pitakrat, T.; Grunske, L.; Grundy, J. Dimensions and metrics for evaluating recommendation systems. Recommendation systems in software engineering 2014, pp. 245–273.

- Guo, J.; Deng, J.; Ran, X.; Wang, Y.; Jin, H. An efficient and accurate recommendation strategy using degree classification criteria for item-based collaborative filtering. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 164, 113756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujatha, P.; Dhavachelvan, P. Precision at K in Multilingual Information Retrieval. International Journal of Computer Applications 2011, 24, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Aberer, K.; Miao, C. Personalized point-of-interest recommendation by mining users’ preference transition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, New York, NY, USA, 2013; CIKM ’13, p. 733–738. [CrossRef]

- Jadon, A.; Patil, A. A comprehensive survey of evaluation techniques for recommendation systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computation of Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning. Springer, 2024, pp. 281–304.

- Rahman, M.M.; Roy, C.K.; Lo, D. Rack: Automatic api recommendation using crowdsourced knowledge. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution, and Reengineering (SANER). IEEE, 2016, Vol. 1, pp. 349–359.

- Smyth, B.; McClave, P. Similarity vs. diversity. In Proceedings of the International conference on case-based reasoning. Springer, 2001, pp. 347–361.

- Hamerly, G.; Elkan, C. Learning the k in k-means. Advances in neural information processing systems 2003, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, M.; Patil, A.; Dalvi, L.; Patil, A. Mini batch K-Means clustering on large dataset. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. Res 2015, 4, 1356–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann, M.R.; Blömer, J.; Kuntze, D.; Sohler, C. Analysis of agglomerative clustering. Algorithmica 2014, 69, 184–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Livny, M. BIRCH: An efficient data clustering method for very large databases. ACM sigmod record 1996, 25, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D. DBSCAN clustering algorithm based on density. In Proceedings of the 2020 7th international forum on electrical engineering and automation (IFEEA). IEEE, 2020, pp. 949–953.

- Ankerst, M.; Breunig, M.M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J. OPTICS: Ordering points to identify the clustering structure. ACM Sigmod record 1999, 28, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueck, D. Affinity propagation: Clustering data by passing messages; University of Toronto Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009.

- Derpanis, K.G. Mean shift clustering. Lecture Notes 2005, 32, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, M.; Welsh, W.J.; Georgopoulos, P. Gaussian mixture clustering and imputation of microarray data. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Luxburg, U. A tutorial on spectral clustering. Statistics and computing 2007, 17, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. Unsupervised deep embedding for clustering analysis. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2016, pp. 478–487.

- Chang, J.; Wang, L.; Meng, G.; Xiang, S.; Pan, C. Deep adaptive image clustering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 5879–5887.

- Hu, W.; Miyato, T.; Tokui, S.; Matsumoto, E.; Sugiyama, M. Learning discrete representations via information maximizing self-augmented training. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2017; pp. 1558–1567. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Tan, H.; Tang, B.; Zhou, H. Variational deep embedding: An unsupervised and generative approach to clustering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.05148 2016.

- Golzari Oskouei, A.; Balafar, M.A.; Motamed, C. EDCWRN: Efficient deep clustering with the weight of representations and the help of neighbors. Applied Intelligence 2023, 53, 5845–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbelaitz, O.; Gurrutxaga, I.; Muguerza, J.; Pérez, J.M.; Perona, I. An extensive comparative study of cluster validity indices. Pattern recognition 2013, 46, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.C. A fuzzy relative of the ISODATA process and its use in detecting compact well-separated clusters 1973.

- Caliński, T.; Harabasz, J. A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Communications in Statistics-theory and Methods 1974, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.L.; Bouldin, D.W. A cluster separation measure. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 1979, pp. 224–227.

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. Journal of computational and applied mathematics 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F.B.; Hubert, L.J. Measuring the power of hierarchical cluster analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1975, 70, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, L.J.; Levin, J.R. A general statistical framework for assessing categorical clustering in free recall. Psychological bulletin 1976, 83, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkidi, M.; Vazirgiannis, M. Halkidi, M.; Vazirgiannis, M. Clustering validity assessment: Finding the optimal partitioning of a data set. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 2001 IEEE international conference on data mining. IEEE, 2001, pp. 187–194.

- Chou, C.H.; Su, M.C.; Lai, E. A new cluster validity measure and its application to image compression. Pattern Analysis and Applications 2004, 7, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Saha, S. A point symmetry-based clustering technique for automatic evolution of clusters. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2008, 20, 1441–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrutxaga, I.; Albisua, I.; Arbelaitz, O.; Martín, J.I.; Muguerza, J.; Pérez, J.M.; Perona, I. SEP/COP: An efficient method to find the best partition in hierarchical clustering based on a new cluster validity index. Pattern Recognition 2010, 43, 3364–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago-Fernández, L.F.; Corbacho, F. Normality-based validation for crisp clustering. Pattern Recognition 2010, 43, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, S.; Raphael, B.; Smith, I.F. A bounded index for cluster validity. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and Data Mining in Pattern Recognition: 5th International Conference, MLDM 2007, Leipzig, Germany, July 18-20, 2007. Proceedings 5. Springer, 2007, pp. 174–187.

- Bezdek, J.C.; Pal, N.R. Some new indexes of cluster validity. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B (Cybernetics) 1998, 28, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, N.R.; Biswas, J. Cluster validation using graph theoretic concepts. Pattern Recognition 1997, 30, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Performance evaluation of some symmetry-based cluster validity indexes. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews) 2009, 39, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Ramakrishna, R. New indices for cluster validity assessment. Pattern Recognition Letters 2005, 26, 2353–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žalik, K.R.; Žalik, B. Validity index for clusters of different sizes and densities. Pattern Recognition Letters 2011, 32, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio-Niño, J.O.; Berzal, F. Evaluation metrics for unsupervised learning algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.05667 2019.

- Tan, P.N.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Introduction to data mining, Pearson education. Inc., New Delhi 2006.

- Xie, X.L.; Beni, G. A validity measure for fuzzy clustering. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis & Machine Intelligence 1991, 13, 841–847. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, G.H. ISODATA, a novel method of data analysis and pattern classification. stanford research institute 1965, pp. AD–699616.

- Hartigan, J.A. Distribution problems in clustering. In Classification and clustering; Elsevier, 1977; pp. 45–71.

- Xu, L. Bayesian Ying–Yang machine, clustering and number of clusters. Pattern Recognition Letters 1997, 18, 1167–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavent, M.; Brito, P. Divisive clustering of histogram data. In Analysis of Distributional Data; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2022; pp. 127–138.

- Gan, G.; Ma, C.; Wu, J. Data clustering: Theory, algorithms, and applications; SIAM, 2020.

- Xiong, H.; Li, Z. Clustering validation measures. In Data clustering; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018; pp. 571–606.

| Metrics | Formula | Evaluation Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (acc) | Ratio of correct predictions over total instances. | |

| Error Rate (err) | Ratio of incorrect predictions over total instances. | |

| Sensitivity (sn) | Fraction of actual positives correctly classified. | |

| Specificity (sp) | Fraction of actual negatives correctly classified. | |

| Precision (p) | Positive patterns correctly predicted from total predicted positives. | |

| Recall (r) | Fraction of positive patterns correctly classified. | |

| F Measure (FM) | Harmonic mean of precision and recall. | |

| Geometric Mean (GM) | Balances true positive and true negative rates. | |

| Mean Square Error (MSE) | Measures difference between predicted and actual values. | |

| AUC | Overall ranking performance of a classifier. | |

| Optimized Precision (OP) | Hybrid metric combining accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. | |

| OARP | Hybrid metric designed for classifier training. | |

| Averaged Accuracy | Average effectiveness across all classes. | |

| Averaged Error Rate | Average error rate across all classes. | |

| Averaged Precision | Average precision across all classes. | |

| Averaged Recall | Average recall across all classes. | |

| Averaged F Measure | Average F1 score across all classes. |

| Metric | Definition |

|---|---|

| Sensitivity () | Proportion of true positives correctly identified: |

| Specificity () | Proportion of true negatives correctly identified: |

| Raw Agreement (I) | Proportion of total agreement: |

| Agreement Due to Chance () | Expected agreement by chance: |

| Cohen’s Kappa () | Agreement corrected for chance: |

| Accuracy | Fraction of correct predictions: |

| Precision | Proportion of true positives among predicted positives: |

| Recall | Proportion of true positives correctly identified: |

| F1-Score | Harmonic mean of precision and recall: |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).