1. Introduction

The adoption of transbronchial lung cryobiopsy (TBLCB) for the evaluation of interstitial lung disease (ILD) has increased as it is a valuable alternative to other modalities such as transbronchial lung forceps biopsy (TBBX). With its widespread implementation, it requires thoughtful implementation of procedural standardization to ensure both diagnostic accuracy and patient safety. One aspect that must be considered is the prompt recognition and management of complications, particularly iatrogenic pneumothorax (IPTX) [

1,

2,

3].

Traditionally, routine post - procedural chest X-Ray (CXR) has been the gold standard for ruling out iatrogenic pneumothorax secondary to TBBX. While CXR is still guideline recommended, there is limited data that compels further investigation into the ideal role of post-TBBX CXR, as it may be avoided in asymptomatic patients [

4]. More supporting evidence is required for widespread acceptance of this practice after forceps transbronchial biopsies and certainly for TBLCB [

5].

Thoracic ultrasonography (TUS) has earned the reputation of being a rapid and highly sensitive imaging modality for pneumothorax detection in different clinical scenarios whether in the intensive care unit or emergency department. Its utility also remains valuable for post-procedural evaluation, however, its role in IPTX detection after TBLCB is not well established. Our early institutional experience incorporating pre and post-TBLCB thoracic ultrasonography (TUS) in comparison to CXR, demonstrates promising utility in ruling out IPTX [

6].

This study evaluates TUS, for the first time, as an alternative to CXR for ruling out IPTX related to TBLCB.

2. Materials and Methods

Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective observational study (CCC # 43022) of 51 consecutive patients that underwent ambulatory TBLCB (between 6/2018 -1/2020 and 3/2021- 2/2023) implementing our TUS protocol. All procedures included in this study were performed by a single operator in a single institution. The following data were collected: age, gender, procedural indication, complications (

Table 1) and management of complications (

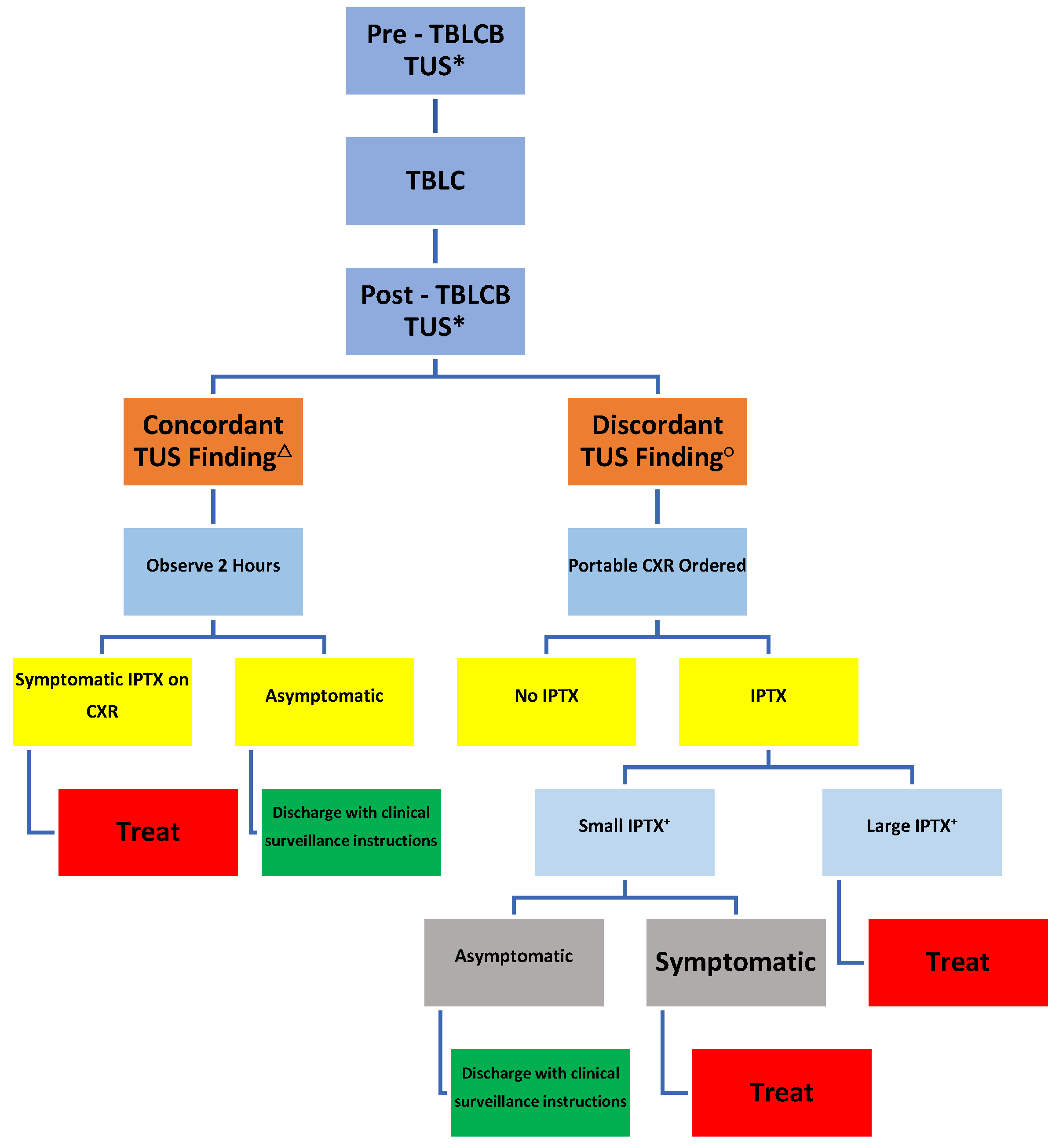

Figure 1).

Bleeding complications were categorized per the Delphi Consensus of the Nashville Working Group (

Table 1).

Per our institutional protocol previously published, all TBLCB’s were performed under general anesthesia via combined rigid ventilating bronchoscopy (i.e., 12mm)/ flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Radial Probe Endobronchial Ultrasonography (RP-EBUS) image guidance and fluoroscopy were integrated. Fogarty balloons (i.e., 4-5 Fr) were positioned in the targeted segmental takeoff and optimal airway blockade confirmed prior to performing TBLCB.

A total of 2-3 segments from 1-3 different lobes from the ipsilateral lung were targeted and biopsied based on chest computerized tomography (CT) findings and RP-EBUS’s confirmation of loss of “snow-storm” effect. Cryobiopsies (2.4 mm outer diameter probes) were performed through the working channel of the flexible bronchoscope under fluoroscopic guidance targeting zone 4 (approximately 1 cm from the pleural). Fogarty balloons were systematically inflated for 2 minutes immediately upon removal of the cryoprobe/flexible bronchoscope as a unit through the barrel of the rigid bronchoscope. After two minutes, slow balloon deflation was performed. If no bleeding was evident, additional biopsies followed in with the same procedural steps as described above. If active bleeding was evident, algorithmic management and grading of the bleed followed.

TUS was performed during spontaneous breathing pre- and immediate post-TBLCB, within 15

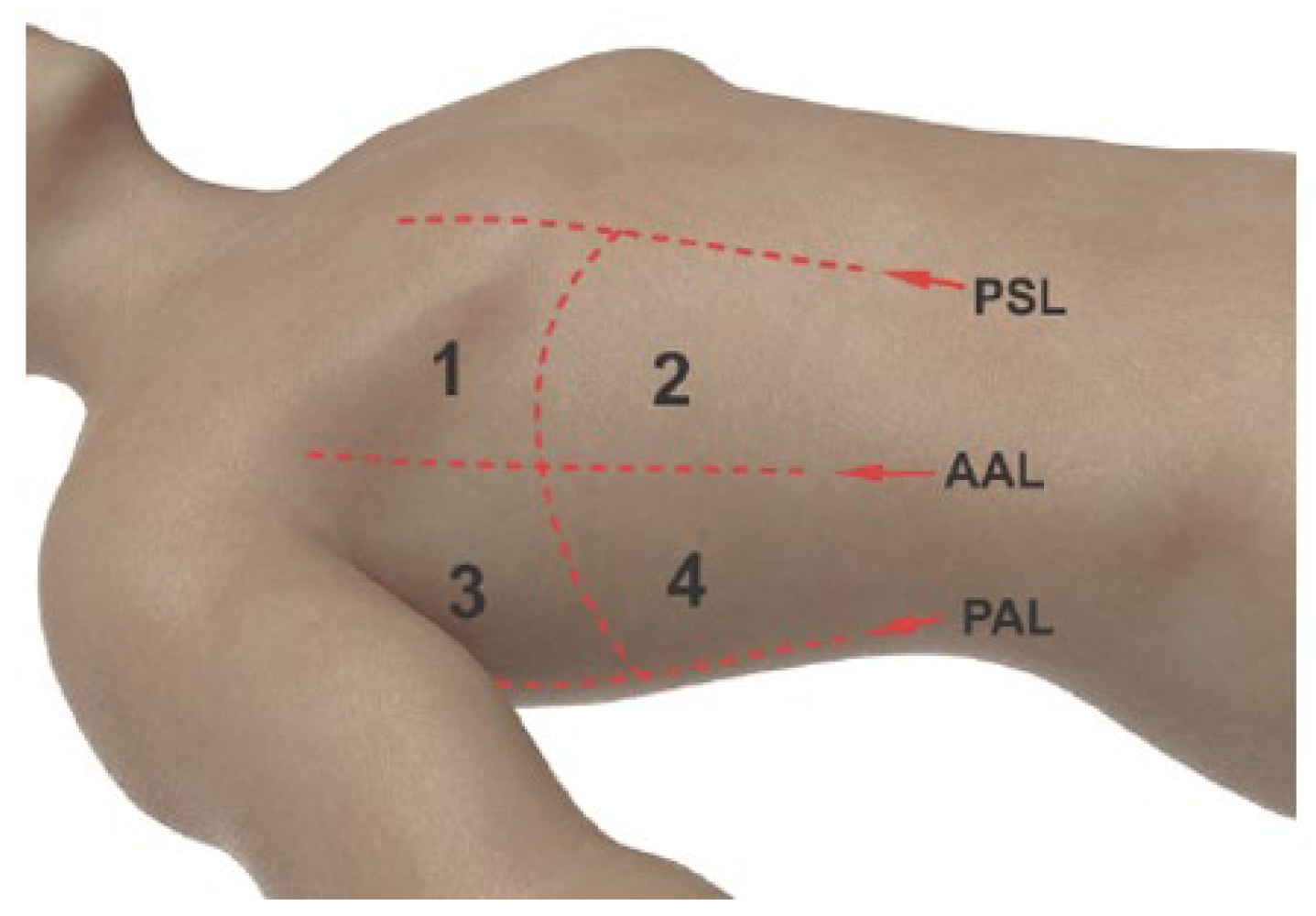

’ of extubation. Four zones were mapped on supine patients based on the parasternal, anterior axillary and posterior axillary lines (

Figure 2). Using a linear array transducer (Z.One Pro, Zonare Medical Systems Inc) in B and M-modes, zones were scanned both longitudinally and transversely for sliding lung (SL) and seashore sign (SS) assessment in both the pre- and immediate post-TBLCB stages of the procedure (

Figure 3A,B). The number of zones demonstrating the presence of both SL and SS signs were documented (i.e., 4 of 4 zones).

Clinically significant IPTX was defined as presence of symptoms (i.e. chest pain, shoulder pain, dyspnea or worsened dyspnea from baseline) and/or signs (i.e. new hypoxia, worsened baseline oxygen saturations with a slow recovery) suggestive of pneumothorax.

Asymptomatic IPTX that met the “large” size criteria (distance of >3 cm from the apex of the collapsed lung to the ipsilateral thoracic cupola) per American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) would also require an intervention.

TUS was used as the sole imaging study if a) both pre- and post-TBLCB TUS images unequivocally demonstrated the presence of both SL and SS signs in 4 of 4 zones (concordant results) and b) patients did not manifest symptoms and/or signs suggestive of clinically significant pneumothorax as above.

Patients additionally received a portable CXR if a) post-TBLCB TUS could not verify presence of SL and SS in all lung zones that were present on pre-TBLCB TUS (discordant results) and/or b) patients manifested symptoms and/or signs suggestive of clinically significant pneumothorax as above.

Patients with pre-TBLCB ultrasonographic features that are non-specific for IPTX were automatically sent for postprocedural CXR and were excluded from the study to minimize the chance of false positive results.

3. Results

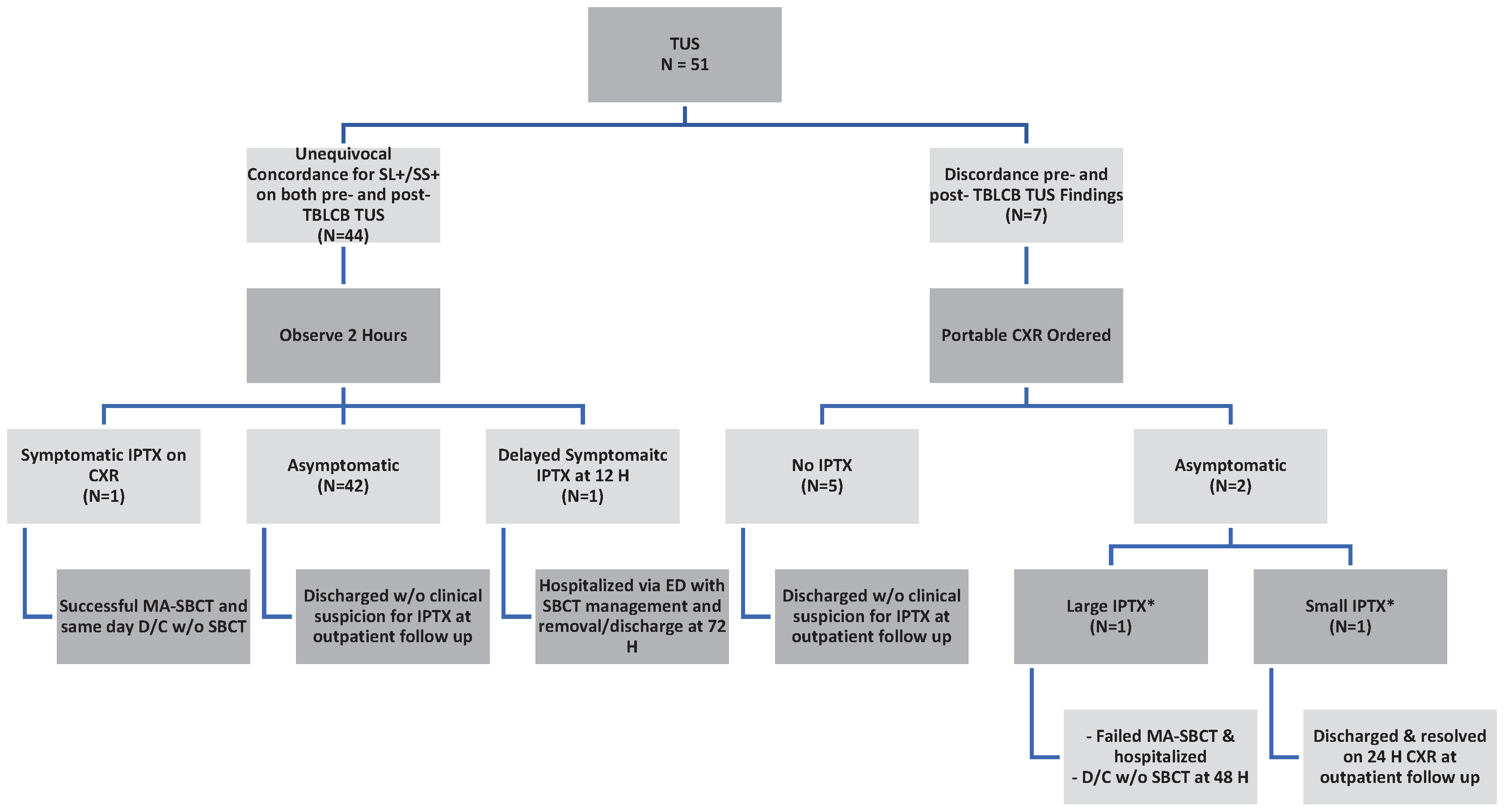

Forty-four (86.1%) patients demonstrated concordant pre- and post-TBLCB TUS findings. Two of 44 (4.5%) developed symptomatic IPTX. Forty-two of 44 (95.45%) patients with concordant TUS findings did not require a CXR. Discordant TUS findings prompted CXR in seven (13.7%) patients. Of these, five (71.4%) were negative for IPTX and two (28.6%) were positive for asymptomatic IPTX. (

Figure 4).

Amongst those with concordant findings on pre- and post TBLCB TUS (N=44), one patient (2.27%) developed symptomatic IPTX and one patient (2.27%) developed symptomatic delayed IPTX after 12 hours. The remaining 95.45% (N=42) were asymptomatic and discharged.

Amongst those with discordant findings on pre- and post- TBLCB TUS (N=7), five (71.43%) were asymptomatic and were discharged after portable CXR proved negative for IPTX. Two (28.57%) had asymptomatic IPTX on portable CXR.

IPTX which required an intervention were considered to be clinically significant. Based on the total 42 of the 44 patients with concordant pre-and post-TBLCB TUS that did not require a subsequent CXR, the negative predictive value of TUS for excluding a clinically significant IPTX was 95.5% (95% CI, 0.89, 1.01); this is an exact Clopper-Pearson interval (

Table 2).

Complications

Four patients (7.8%) developed pneumothorax, of which two (3.9%) were clinically significant requiring interventions - one successfully treated and discharged after ambulatory-based manual aspiration (MA) via a small-bore chest tube (SBCT) and one requiring hospitalization with SCBT placement and removal at discharge within 48 hours. This management strategy was guided by our algorithm for the management of transbronchial biopsy-related IPTX [

7].

Two (3.9%) had asymptomatic IPTX; one large per ACCP criteria which required hospitalization after failing ambulatory management with MA via SBCT, followed by discharge after SBCT removal at 48H. The second was small per ACCP criteria and demonstrated complete radiographic resolution on a follow up PA/Lateral outpatient CXR.

Bleeding complications were classified according to the Delphi Consensus Statement of the Nashville Working Group. Five patients (9.8%) developed bleeds. One (1.96%) developed Grade 1 and four (7.8%) developed Grade 2 bleeds. No Grade 3 or 4 bleeds occurred.

No mortality was reported.

4. Discussion

TBLCB has established its role in clinical practice guidelines as a safe and acceptable alternative for undetermined interstitial lung diseases in medical centers capable of performing and interpreting TBLCB [

8,

9,

10]. As TBLCB becomes more widely adopted, prompt identification and management of complications should be integral to standardized procedural approaches [

6]. Without defined and accepted procedural protocols, complications may be higher [

11].

Pneumothorax complicates TBBX in 1-6% of cases, with a higher incidence of 6-20.9% for TBLCB [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. A meta-analysis of 68 studies evaluating the safety and diagnostic yield of TBLCB in 6386 patients by Zayed et al. reported a pneumothorax rate of 9.6% [

21]. Proposed risk factors that can increase the prevalence of IPTX after TBLCB may be due to low total lung capacity (TLC) and reduced diffusion capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) [

19].

CT scan is the gold standard for diagnosing pneumothorax; however, due to its high cost and radiation exposure, it is not recommended as a first-line imaging modality [

22,

23]. Therefore, erect CXR has historically been the modality of choice for diagnosing IPTX following TBBX. The British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines recommend performing an erect CXR 1-hour post biopsies based on Perlmutt et al.

’s detection of 98% of significant pneumothoraces within the first hour of the biopsy procedure [

24,

25].

TUS is a safe, radiation-free, and cost-effective imaging modality whose role in the detection of IPTX has evolved since Lichtenstein and Menu first demonstrated its value in excluding IPTX in critically ill [

26]. Its applications have since expanded beyond the intensive care unit to also detect and rule-out PTX in trauma patients with superiority over CXR, additionally in the detection of IPTX post-TBBX and specifically post-TBBX in lung transplant recipients [

27,

28,

29,

30].

Indeed, TUS is more accurate than CXR, particularly in ruling out PTX of different etiologies [

6,

23,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Herein, our study adds to this body of literature with our results of a 95% negative predictive value (NPV) for the exclusion of post-TBLCB IPTX.

Our strategy of obtaining TUS imaging before and after TBLCB is based on concerns that potential false-positive findings for IPTX can be recognized by identifying pre-TBLCB ultrasonographic features that are non-specific for IPTX. Such cases with these pre-TBLCB ultrasonographic features should automatically qualify for a postprocedural CXR, as post-TBLCB TUS would be rendered unreliable. We speculate and concur with other investigators that false positives may be secondary to altered lung anatomy in the selected patient population as they may have underlying lung pathology, previous lung surgeries, or the use of radiation therapy, which may cause pleural adhesions and loss of lung sliding [

28,

31].

Guidelines recommend that CXR should be performed after TBBX. Interestingly, Izbicki et al. suggested that routine CXR after TBBX is not necessary and can be safely avoided specifically in asymptomatic patients without significant oxygen desaturation events, as pneumothorax is rare and of negligible clinical significance in these patients [

4].

Delayed pneumothorax can occur as reported in one of our patients. Unfortunately, literature describing the incidence and timing of occurrence of delayed IPTX after lung biopsies is not available. We must therefore ensure appropriate education is given to instruct patients to seek emergent care if any concerning symptoms arise.

Although not the focus of this study, it is worthwhile mentioning that the implementation of our institutional protocol for the management of IPTX with manual aspiration via a small-bore chest tube can be a safe and feasible alternative for this complication following TBBX and TBLCB [

40]. This approach encourages more individualized care supporting the ambulatory management of IPTX.

Overall, this study challenges the practice of using CXR to rule out IPTX. If validated, the use of TUS as the first line modality would shift procedural guidelines, while CXR can be used in select cases, which is in alignment with the evidence brought forth in our study. By implementing this, TUS can reduce radiation exposure, especially in those who require frequent imaging.

As we highlight the encouraging NPV of TUS for ruling out clinically significant IPTX with TBLCB, we acknowledge our study’s inherent limitations in being a single operator at a single center in addition to a smaller sample size. Larger, multicenter studies with a diverse patient population and multiple operators utilizing TUS as a diagnostic modality would further validate our results. Further studies may be necessary to implore the cost - effectiveness for both hospitals and patients when utilizing TUS instead of CXR for evaluating IPTX.

5. Conclusions

Applying our TUS protocol for ruling out clinically significant IPTX avoided routine CXR in 95.5% of patients, suggesting its role as a safe alternative to routine CXR in post-TBLCB patients. However, the absence of sliding lung and/or seashore sign or presence of suspicious symptoms and/or signs should prompt a CXR, as IPTX needs to be excluded. Delayed IPTX can occur and regardless of the imaging modality used for the evaluation of IPTX, patients do require specific symptom surveillance instructions. Future studies are required to support our findings and ideally evaluate upon broadening this approach for all forms of bronchoscopic sampling for diverse indications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M.; methodology, I.M.; validation, I.M, S.A, and V.M.; formal analysis, I.M, S.A, and V.M.; investigation, I.M.; resources, I.M.; data curation, I.M, S.A, and V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M, S.A, and V.M; writing—review and editing, I.M, S.A, and V.M.; visualization, I.M, S.A, and V.M.; supervision, I.M.; project administration, I.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Christiana Care (CCC #43022 3/30/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not obtained from subjects involved in the study due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

No data availability statement.

Acknowledgments

No acknowledgements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Du Rand IA, Blaikley J, Booton R, et al. British Thoracic Society bronchoscopy guideline group. British Thoracic Society guideline for diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy in adults: accredited by NICE. Thorax. 2013;68 (Suppl 1): 1-i44. [CrossRef]

- Facciolongo N, Patelli M, Gasparini S, et al. Incidence of complications in bronchoscopy. Multicentre prospective study of 20,986 bronchoscopies. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2009;71:8–14.

- Pue CA, Pacht ER. Complications of fiberoptic bronchoscopy at a university hospital. Chest 1995;107:430–2. [CrossRef]

- Colt HG, Matsuo T. Hospital charges attributable to bronchoscopy-related complications in outpatients. Respiration 2001;68:67–72. [CrossRef]

- Milman N, Faurschou P, Munch EP, et al. Transbronchial lung biopsy through the fibre optic bronchoscope. Results and complications in 452 examinations. Respir Med 1994;88:749–53.

- Matus I, Raja H. Protocolized thoracic ultrasonography in transbronchial lung cryobiopsies: a potential role as an exclusion study for pneumothorax. J Broncholo Intervent Pulmonolo 2018;26:172-178 .

- Ultrasound Lung Zones. https://www.teachingmedicine.com/Lesson.aspx?l_id=95.

- Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, Thomson CC et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J REspir Crit Care Med. 2022 May 1; 205 (9):e18-e47. 7. [CrossRef]

- Ravaglia C, Wells A.U., Tomassetti S et al. Diagnostic yield and risk/benefit analysis of transbronchial lung cryobiopsy in diffuse parenchymal lung diseases: a large cohort of 699 patients. BMC Pulm Med 2019, 19:16. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado F, Danoff SK, Wells AU et al. Transbronchial Cryobiopsy for the Diagnosis of Interstitial Lung Diseases: Chest. 2020 Apr; 157 (4): 1030-1042. [CrossRef]

- Korevaar DA, Colella S, Fally M, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines on transbronchial biopsy in the diagnosis of interstital lung diseases. Eur Respir J 2022;60:2200425.

- Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022; 205:e18-e47. [CrossRef]

- Dibardino D, Haas A, Lanfranco A, et al. High complication rate after introduction of transbronchial cryobiopsy into clinical practice at an academic medical center. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:851–885. [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar IH, Alghothani L, Sardi A, Berkowitz D, Musani AI. Transbronchial Lung Cryobiopsy and Video-assisted Thoracoscopic Lung Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Disease. A Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(7):1197-1211. [CrossRef]

- C. Sharp, M. McCabe, H. Adamali, A.R. Medford, Use of transbronchial cryobiopsy in the diagnosis of interstitial lung disease—a systematic review and cost analysis, QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, Volume 110, Issue 4, April 2017, Pages 207–214, . [CrossRef]

- Zayed Y, Alzghoul BN, Hyde R, et al. Role of Transbronchial Lung Cryobiopsy in the Diagnosis of Interstitial Lung Disease: A Meta-analysis of 68 Studies and 6300 Patients. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2023;30(2):99-113. Published 2023 Apr 1. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D., Raíces, M., Bequis, M. A., Las Heras, M. ., Wainstein, E., Castro, R., Montagne, J., & Dietrich, A. (2021). Post-transbronchial biopsy complications: the role of cryobiopsy in the incidence of postoperative pneumothorax. Journal of the Faculty of Medical Sciences of Córdoba, 78(1), 29–32. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso ACG, Serino M, Coelho DB, et al. Predictors of pneumothorax after transbronchial lung cryobiopsy for diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases. European Respiratory Journal. 2021;58(suppl 65). [CrossRef]

- Davidsen, J.R., Skov, I.R., Louw, I.G. et al. Implementation of transbronchial lung cryobiopsy in a tertiary referral center for interstitial lung diseases: a cohort study on diagnostic yield, complications, and learning curves. BMC Pulm Med 21, 67 (2021). [CrossRef]

- MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J. Group BTSPDG: management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guidelines 2010. Thorax. 2010;65(suppl 2):ii18–ii31. [CrossRef]

- Baumann MH, Strange C, Heffner JE, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: an American College of Chest Physicians Delphi consensus statement. Chest. 2001;119:590–602.

- Manhire A, Charig M, Clelland C, et al Guidelines for radiologically guided lung biopsy Thorax 2003;58:920-936. [CrossRef]

- Perlmutt L, Braun S, Newman G, Oke E, Dunnick N. Timing of chest film follow-up after transthoracic needle aspiration. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1986;146(5):1049-1050. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein DA, Menu Y. A bedside ultrasound sign ruling out pneumothorax in the critically ill. Chest. 1995;108:1345–1348. [CrossRef]

- Krueter M, Eberhardt R, Wenz H, et al. Diagnostic value of transthoracic ultrasound compared to chest radiography in the detection of a post-interventional pneumothorax. Ultraschall Med. 2011;32(suppl 2):E2–E23.

- Kumar S, Agarwal R, Aggarwal An, et al. Role of ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of pneumothorax following transbronchial lung biopsy. J Bronchol Intervent Pulmonol. 2015;22:14–19. [CrossRef]

- Bensted K, McKenzie J, Havryk A, et al. Lung ultrasound after transbronchial biopsy for pneumothorax screening in post-lung transplant patients. J Bronchol Intervent Pulmonol. 2018;25:42–47. [CrossRef]

- Viglietta L, Inchingolo R, Pavano C, et al. Ultrasonography for the diagnosis of pneumothorax after trans bronchial lung cryobiopsy in diffuse parenchymal lung diseases. Respiration. 2017;94:232–236. [CrossRef]

- Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M, et al. International evidence-based recommendations for point of care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:577–591.

- Elbarbary M, Melniker LA, Volpicelli G, et al. Development of evidence-based clinical recommendations and consensus statements in critical ultrasound field: why and how? Crit Ultrasound J. 2010;2:93–95. [CrossRef]

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, et al. A GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:380–382. [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick AW, Sirois M, Laupland KB, et al. Hand-held thoracic sonography for detecting post-traumatic pneumothoraces: the extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (EFAST). J Trauma. [CrossRef]

- Volpicelli G. monographic diagnosis of pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:224–232.

- Blaivas M, Lyon M, Duggal S. A prospective comparison of supine chest radiography and bedside ultrasound for the diagnosis of traumatic pneumothorax. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:844–849. [CrossRef]

- Rowan KR, Kirkpatrick AW, Liu D, et al. Traumatic pneumothorax detection with thoracic US: correlation with chest radiography and CT—initial experience. Radiology. 2002;225:210–214. [CrossRef]

- Soldati G, Testa A, Pignataro G, et al. The ultrasonographic deep sulcus sign in traumatic pneumothorax. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:1157–1163. [CrossRef]

- Soldati G, Testa A, Sher S, et al. Occult traumatic pneumothorax: diagnostic accuracy or lung ultrasonography in the emergency department. Chest. 2008;133:204–2011.

- Zhang M, Liu ZH, Yang JX, et al. Rapid detection of pneumothorax by ultrasonography in patients with multiple trauma. Crit Care. 2006;10:R112. [CrossRef]

- Izbicki G, Romem A, Arish N, et al. Avoiding Routine Chest Radiography after Transbronchial Biopsy Is Safe. Respiration. 2016;92(3):176-181. [CrossRef]

- Matus I, Mertens A, Wilton S, Raja H, Roedder T. Safety and Efficacy of Manual Aspiration Via Small Bore Chest Tube in Facilitating the Outpatient Management of Transbronchial Biopsy-related Iatrogenic Pneumothorax. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2021 Oct 1;28(4):272-280. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).