Introduction

The role of local anaesthetic thoracoscopy (LAT) is in investigating unexplained exudative pleural effusions is well established. It offers a one stop approach for relieving symptoms, namely breathlessness, by draining pleural effusions; for diagnosis by allowing biopsies of abnormal areas of parietal pleura under direct vision and finally for therapeutic purposes by enabling pleurodesis via talc slurry or poudrage or fluid control by indwelling pleural catheter (IPC) insertion [

1]. The technique, indications and evidence are well described in international guidelines and in expert opinions.

One of the complications described is surgical emphysema (SE). SE, air in the subcutaneous tissues occurs when air escapes from the alveolar/pleural spaces due to pneumothoraces for example, or from diffuse infections due to gas forming organisms, trauma to the chest or procedures such as cardiothoracic surgery (incidence approximately 6 per cent [%]) or even abdominal laparoscopy [

3,

4,

5]. A palpable shift in practice in the UK has been the increasing provision of day case LAT with IPC insertion [

6,

7,

8]. LAT has typically required admission thereafter with a large bore chest drain inserted at the end of the LAT, but insertion of an IPC instead allows same day discharge [

9]. SE is one of those complications which might prevent same day discharge, as it might signify an air leak, presumably from rupture of the visceral pleura. Expert opinion is divided- whilst the guidance suggest that SE is a measurable complication, others such as the senior authors in this paper, would argue that without a concurrent air leak, the presence of SE is of no clinical significance.

Some expert thoracoscopists from other UK centres advocate the concurrent insertion of a large bore chest drain and an IPC to reduce SE, and others advocate insertion of the IPC at different entry site from the one done to perform LAT [

10].

We hypothesised that SE post day case LAT with concurrent IPC insertion, in the absence of an air leak, is of no clinical significance. SE requires no further large bore drain insertion and can be inserted into the same entry site used for the LAT.

Methods

We performed a case note review of all consecutive patients undergoing day case LAT and IPC insertion in 3 UK based centres (Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust and Kettering General Hospital) performing day case LAT with IPC insertion. We collected demographics and clinically relevant outcomes. This was registered as a multicentre audit with local information governance approval from Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (Ref 8491). Informed consent was not required as this was a retrospective audit with anonymised data shared. Continuous variables are presented as median with interquartile range and categorical variables were expressed as frequencies (n) and percentages (%).

A short description of how LAT is performed is also warranted- after all the required pre-procedural safety checks, the patient is placed into the lateral decubitus position with the affected side facing upwards. After the patient is sedated, the site of the port of entry is identified with thoracic ultrasound and local anaesthetic infiltrated. An incision is made with a scalpel and entry to the pleural space is obtained either with blunt dissection or with Boutin needles. An artificial pneumothorax is created, pleural fluid suctioned out, and after visual inspection of the parietal pleura, targeted biopsies can be taken. In two centres, an IPC (Rocket Medical PLC) is inserted through the same hole as the initial LAT port, and the drain brought out 5 centimetres distally, and at one site, an IPC (PleurX Pleural Catheter System) is inserted at different site from LAT. At the end of the procedure, the IPC is connected to an underwater drainage bottle, and a chest x-ray (CXR) is performed. In the absence of bubbling from the drain (signifying no visceral air leak), and satisfactory drain position placement on the CXR, the IPC is capped and the patient discharged once they have sufficiently recovered from the procedure. No digital suction devices were used. Only 1 centre (Kettering General Hospital) performs routine talc pleurodesis via poudrage at the time of LAT in patients with macroscopically suspicious pleura.

Results

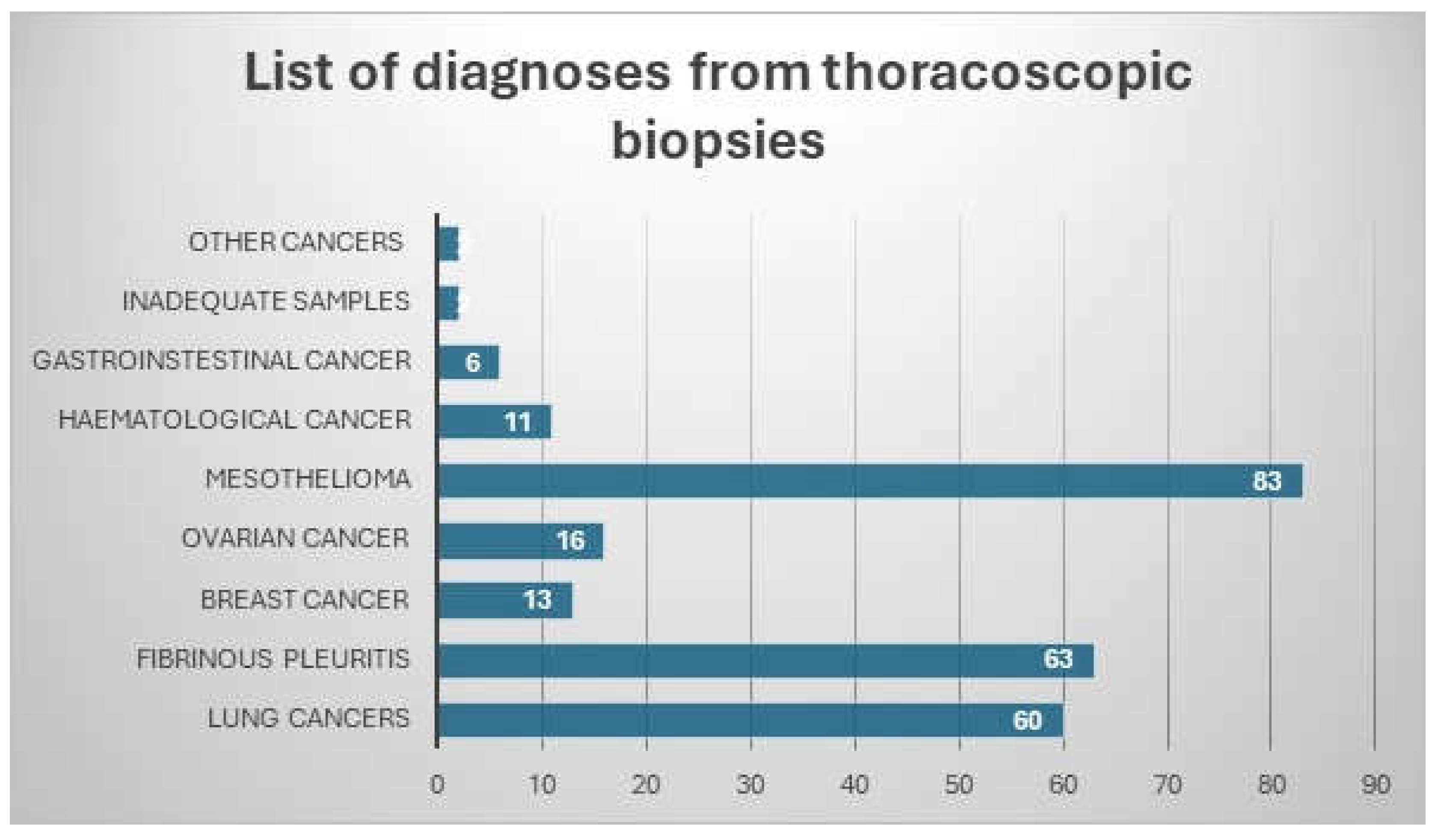

From locally held procedure lists, 256 day case LATs were identified between July 2020 and January 2024. The mean age across the whole cohort was 72 years (IQR 14.5) and 93 (36.3%) patients were male. The predominant diagnoses were mesotheliomas (83,32.4%), lung cancers (60,23.4%) and benign pleuritis (63,24.6%). This is shown in

Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 showing list of diagnoses from thoracoscopic pleural biopsies 64 patients (25%) developed post procedure SE. This group had a median age 71.3 years, IQR 14, were predominantly female patients (45, 70%), diagnoses were predominantly mesothelioma (32, 50%) and lung cancer (20, 31%), with the others being breast [

3] and ovarian cancer (2), and benign inflammation (7) and 4 of those had concurrent air leaks. In those, there were no instances of visceral pleural puncture or lung injury, and all the air leaks were felt due to the pleural surfaces and lung shearing away at pneumothorax induction during the initial stages of LAT.

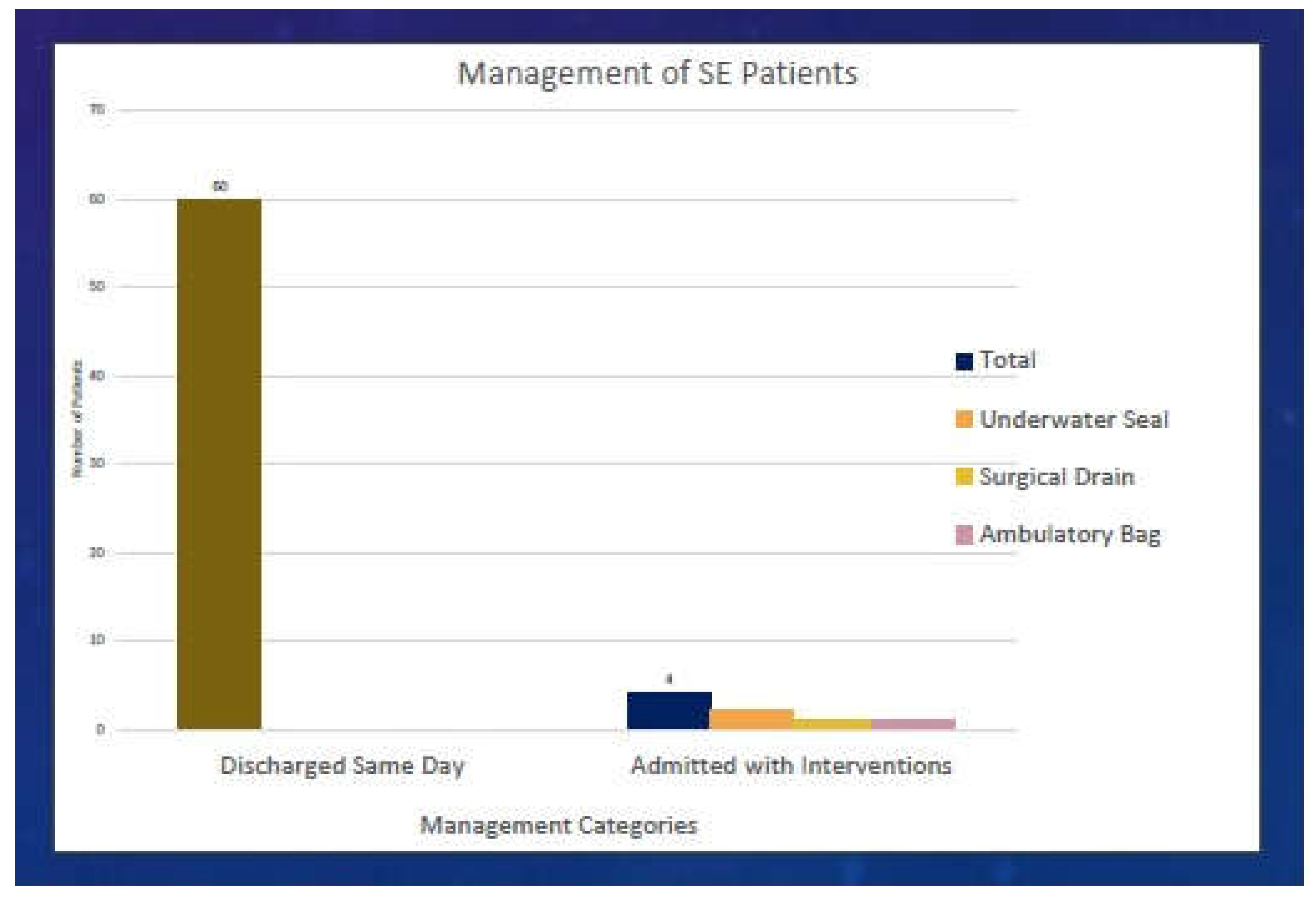

Of those 4 patients, specifically, 3 had non expandable lung at thoracoscopy and on the post procedure chest x-ray (CXR), and 3 diagnoses were mesothelioma and 1 had lung cancer. 3 were admitted post procedure. In 3 patients, the IPC remained connected to a chest drain bottle, and in 2, the air leak settled after an average of 4 days. There was no requirement for large bore drain insertion. In the final one in this group, as the patient was very well and ambulant, an ambulatory bag was connected to the IPC on the day of the procedure, enabling same day discharge - the air leak settled in 4 days after discharge. One patient’s SE progressed despite the IPC being connected to a chest drain bottle, signifying that the diameter of the IPC was not sufficient for that air leak, and so a 24French Gauge (Fr) chest drain was inserted with air leak resolution at 3 days.

Figure 2 shows the management of patients with SE.

Discussion

Our retrospective data, from a multi-centre audit of practice, signals that SE at the end of day case LAT with IPC insertion, in the absence of air leak, is of no clinical consequence. Whilst this is not a formal randomised trial with control groups, we believe the data can be practice changing given that LAT practice is increasing throughout the UK, and worldwide [

6,

11]. This is a large dataset coming from experienced LAT centres and contains simple observational data.

We refrained from doing formal statistical comparisons given how the data was collected, and we did not measure the severity of the SE as we found at an interim analysis of the data (at the end of the analysis of the data from Northumbria Healthcare NHS Trust) that the severity of the SE had no clinical significance. Note that SE can be graded 0-4 (0 being SE seen, 1 is SE just the LAT or IPC site, 2 is involving the ipsilateral hemithorax, 3 is all the above and involving the neck on the same side, and 4 is involving the contralateral hemithorax) [

12]. We also did not measure the incidence of non-expandable lung as all the patients had an IPC inserted. The definition of clinically significant SE is also debatable- unless there is an active air leak, SE is benign and will resolve [

13]. All the centres in this study also have a practical approach and do not repeat chest radiographs to see if the SE resolves.

Day case LAT was started at the start of Coronavirus 19 pandemic where bed pressures across healthcare systems were increased and day case thoracoscopy and IPC insertion allowed same day discharge, thus freeing up beds. Two of the centres in this study have published preliminary findings about this practice, both showing the feasibility and cost savings associated with day case LAT [

7,

8].

The mechanism of SE during LAT is due to air escaping into the subcutaneous tissues from the pleural space. This can be totally expected as the air from the artificial pneumothorax can seep out. More importantly, lung injury during the LAT procedure can cause an air leak which would be picked up by continuous bubbling into the chest drain bottle after the procedure. The IPC drain is a 16 French gauge (Fr) drain, and is approximately 5.3mm in diameter, and there is concern from other centres that the 16Fr drain is just not enough for SE and that additional large bore (traditionally defined as more than 20Fr) should be inserted through the LAT port with the IPC in another intercostal space [

10]. This was the case in one of our patients where additional chest drainage was required. We do not formally measure our air leaks with digital suction devices and go via the assessment of bubbling into the chest drain- this cannot be measured retrospectively [

14].

The largest meta-analysis of complications from thoracoscopy comes from Martinez-Zayas et al., where 90 studies were reviewed, and overall pooled complication rates were low at 0.040 (95% confidence interval: 0.029–0.052) [

15]. SE is consistently included in most of the studies as a complication, whereas we would argue that it is simply a clinical phenomenon that is very common with LAT, due to the techniques used to do LAT [

10]. As such, whether this SE is a true complication of LAT is perhaps debatable. The British Thoracic Society (BTS) Clinical Statement on pleural procedures also suggests that that most SE in the context of LAT is benign and will resolve spontaneously. However, the BTS statement suggests as a good practice point, that the IPC post LAT insertion should be inserted in another rib space [

16]. Our data from two out of three centres would suggest that placement of the IPC into the initial LAT port (99 procedures in total) is feasible, safe, and any resultant SE is benign.

Conclusions and Future Directions

In the absence of simultaneous air leaks, the presence of SE in day case LAT with IPC insertion is of no clinical importance. The pleural community should move away from including it as a complication. Concurrent drainage of air via IPCs and surgical drains are not required. However, until formal randomised controlled trials are performed (day case LAT with IPC versus day case LAT with IPC and large bore drain insertion, and IPC insertion in the same intercostal space versus a different one), expert opinions and retrospective reviews can provide the evidence base required to inform practice.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval

Multicentre audit from Northumbria Healthcare (Ref 8491).

Informed Consent Statement

As this was a retrospective review, there was no required for informed consent from the participants.

Conflict of Interest (COI) statements

Avinash Aujayeb is part of the Editorial team for Journal of respiration, but was not involved in peer reviewer selection. None of the other authors have anything to declare.

Data Availability Statements (DAS)

Some of the data will be available with reasonable requests.

Conflicts of Interest

As above.

References

- Aujayeb, A.; Astoul, P. Use of medical thoracoscopy in managing pleural malignancy. Breathe 2024, 20, 230174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts ME, Rahman NM, Maskell NA On behalf of the BTS Pleural Guideline Development Group, et al.British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease Thorax 2023;78:s1-s42.

- Zakaria, R.; Khwaja, H. Subcutaneous emphysema in a case of infective sinusitis: a case report. J. Med Case Rep. 2010, 4, 235–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodhia, J.V.; Tenconi, S. Postoperative subcutaneous emphysema: prevention and treatment. Shanghai Chest 2021, 5, 17–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, D.E. Subcutaneous Emphysema—Beyond the Pneumoperitoneum. JSLS : J. Soc. Laparosc. Robot. Surg. 2014, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseka DD, Aujayeb A, Bhatnagar R S27 UK local anaesthetic thoracoscopy services in 2024 Thorax 2024;79:A25.

- Kiran, S.; Mavilakandy, A.; Rahim, S.; Naeem, M.; Rawson, S.; Reed, D.; Tsaknis, G.; Reddy, R.V. The role of day-case thoracoscopy at a district general hospital: A real world observational study. Futur. Heal. J. 2024, 11, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, M.; Craighead, F.; MacKenzie, J.D.; Aujayeb, A. Day Case Local Anaesthetic Thoracoscopy: Experience from 2 District General Hospitals in the United Kingdom. Med Sci. 2023, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aujayeb, A.; Jackson, K. A review of the outcomes of rigid medical thoracoscopy in a large UK district general hospital. Pleura Peritoneum 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajmal S, Stockbridge A, Johnstone S, et al. Subcutaneous Emphysema Risk Following Indwelling Pleural Catheter Insertion During Rigid Local Anesthetic Thoracoscopy: Via Thoracoscopy Port Versus Separate Incision Site. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2023 Oct 1;30(4):368-372.

- Madan, K.; Tiwari, P.; Thankgakunam, B.; Mittal, S.; Hadda, V.; Mohan, A.; Guleria, R. A survey of medical thoracoscopy practices in India. Lung India 2021, 38, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas N, Ben P, Samantha S, et al. The risk of surgical emphysema post VATS pleural biopsy and IPC. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(Suppl 63):PA1079.

- Melhorn, J.; Davies, H.E. The Management of Subcutaneous Emphysema in Pneumothorax: A Literature Review. Curr. Pulmonol. Rep. 2021, 10, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, K.C.; Laxmanan, B.; Murgu, S.; Hogarth, D.K. Management of Persistent Air Leaks. Chest 2017, 152, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Zayas, G.; Molina, S.; Ost, D.E. Sensitivity and complications of thoracentesis and thoracoscopy: a meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 220053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asciak R, Bedawi EO, Bhatnagar R, et al. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on pleural procedures Thorax 2023;78:s43-s68.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).