Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Material and Method

Patient Enrolment

Laboratory Parameters

Statistical Analysis

Results

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDW | Monocyte distribution width; |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2; |

| AUC | Area under the curve; |

| ICU | Intensive care unit; |

| K2EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-K2; |

| CRP | C-reactive protein; |

| PCT | Procalcitonin; |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic; |

| CBC | Complete Blood Count; |

| SOFA | Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; |

| CPD | Cell Population Data; |

| BSI | Bloodstream infections; |

References

- Farkas JD. The complete blood count to diagnose septic shock. J Thorac Dis. 2020 Feb;12(Suppl 1):S16-S21. [CrossRef]

- Lorubbio M. and Ognibene A. Il contributo dell’esame emocromocitometrico nella diagnosi di infezione e sepsi Biochimica Clinica, 48 (4) 381-383 - 2024.

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):801-10. [CrossRef]

- Manu Shankar-Hari 1 , Gary S Phillips 2 , Mitchell L Levy 3 , Christopher W Seymour 4 , Vincent X Liu 5 , Clifford S Deutschman 6 , Derek C Angus 7 , Gordon D Rubenfeld 8 , Mervyn Singer 9 ; Developing a New Definition and Assessing New Clinical Criteria for Septic Shock: For the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) Sepsis Definitions Task Force JAMA . 2016 Feb 23;315(8):775-87.

- Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, Brunkhorst FM, Rea TD, Scherag A, Rubenfeld G, Kahn JM, Shankar-Hari M, Singer M, Deutschman CS, Escobar GJ, Angus DC. Assessment of Clinical Criteria for Sepsis: For the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8):762-74. Erratum in: JAMA. 2016 May 24-31;315(20):2237. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0288. [CrossRef]

- Markwart R, Saito H, Harder T, Tomczyk S, Cassini A, Fleischmann-Struzek C, Reichert F, Eckmanns T, Allegranzi B. Epidemiology and burden of sepsis acquired in hospitals and intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020 Aug;46(8):1536-1551. [CrossRef]

- Cecconi M, Evans L, Levy M, Rhodes A. Sepsis and septic shock. Lancet. 2018 Jul 7;392(10141):75-87.

- Evans T. Diagnosis and management of sepsis. Clin Med (Lond). 2018 Mar;18(2):146-149.

- Naghavi M, Vollset SE, Ikuta KS, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990-2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024;404:1199–226. [CrossRef]

- Verway M, Brown KA, Marchand-Austin A, et al. Prevalence and mortality associated with bloodstream organisms: a population-wide retrospective cohort study. J Clin Microbiol 2022;60(4) . [CrossRef]

- Hassoun-Kheir N, Guedes M, Ngo Nsoga MT, et al. A systematic review on the excess health risk of antibiotic-resistant bloodstream infections for six key pathogens in Europe. S14-s25 Clin Microbiol Infect 2024;30(1). [CrossRef]

- Allel K, Stone J, Undurraga EA, et al. The impact of inpatient bloodstream infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2023;20:21 . [CrossRef]

- Tabah A, Koulenti D, Laupland K, Misset B, Valles J, Bruzzi de Carvalho F, Paiva JA, Cakar N, Ma X, Eggimann P, Antonelli M, Bonten MJ, Csomos A, Krueger WA, Mikstacki A, Lipman J, Depuydt P, Vesin A, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Zahar JR, Blot S, Carlet J, Brun-Buisson C, Martin C, Rello J, Dimopoulos G, Timsit JF. Characteristics and determinants of outcome of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections in intensive care units: the EUROBACT International Cohort Study. Intensive Care Med. 2012 Dec;38(12):1930-45. [CrossRef]

- Crouser ED, Parrillo JE, Seymour CW, et al. Monocyte distribution width: a novel indicator of sepsis-2 and sepsis-3 in high-risk emergency department patients. Crit Care Med 2019;47:1018–25. [CrossRef]

- Crouser ED, Parrillo JE, Martin GS, et al. Monocyte distribution width enhances early sepsis detection in the emergency department beyond SIRS and qSOFA. J Intens Care 2020;8:33. [CrossRef]

- Polilli E, Sozio F, Frattari A, et al. Comparison of monocyte distribution width (MDW) and procalcitonin for early recognition of sepsis. PLoS ONE 2020;15: . [CrossRef]

- Agnello L, Ciaccio AM, Del Ben F, Lo Sasso B, Biundo G, Giglia A, Giglio RV, Cortegiani A, Gambino CM, Ciaccio M. Monocyte distribution width (MDW) kinetic for monitoring sepsis in intensive care unit. Diagnosis (Berl). 2024 Apr 22;11(4):422-429. [CrossRef]

- Agnello L, Ciaccio AM, Vidali M, Cortegiani A, Biundo G, Gambino CM, Scazzone C, Lo Sasso B, Ciaccio M. Monocyte distribution width (MDW) in sepsis. Clin Chim Acta. 2023 Aug 1;548:117511. [CrossRef]

- Ognibene A, Lorubbio M, Montemerani S, Tacconi D, Saracini A, Fabbroni S, Parisio EM, Zanobetti M, Mandò M, D'Urso A. Monocyte distribution width and the fighting action to neutralize sepsis (FANS) score for sepsis prediction in emergency department. Clin Chim Acta. 2022 Sep 1;534:65-70. [CrossRef]

- Campagner A, Agnello L, Carobene A, Padoan A, Del Ben F, Locatelli M, Plebani M, Ognibene A, Lorubbio M, De Vecchi E, Cortegiani A, Piva E, Poz D, Curcio F, Cabitza F, Ciaccio M. Complete Blood Count and Monocyte Distribution Width-Based Machine Learning Algorithms for Sepsis Detection: Multicentric Development and External Validation Study. J Med Internet Res. 2025 Feb 26;27:e55492. [CrossRef]

- Ognibene A, Lorubbio M, Magliocca P, Tripodo E, Vaggelli G, Iannelli G, Feri M, Scala R, Tartaglia AP, Galano A, Pancrazzi A, Tacconi D. Elevated monocyte distribution width in COVID-19 patients: The contribution of the novel sepsis indicator. Clin Chim Acta. 2020 Oct;509:22-24. [CrossRef]

- Lorubbio M, Tacconi D, Iannelli G, Feri M, Scala R, Montemerani S, Mandò M, Ognibene A. The role of Monocyte Distribution Width (MDW) in the prognosis and monitoring of COVID-19 patients. Clin Biochem. 2022 May;103:29-31. [CrossRef]

- Malinovska A, Hernried B, Lin A, Badaki-Makun O, Fenstermacher K, Ervin AM, Ehrhardt S, Levin S, Hinson JS. Monocyte Distribution Width as a Diagnostic Marker for Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest. 2023 Jul;164(1):101-113.

- Huang YH, Chen CJ, Shao SC, Li CH, Hsiao CH, Niu KY, Yen CC. Comparison of the Diagnostic Accuracies of Monocyte Distribution Width, Procalcitonin, and C-Reactive Protein for Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2023 May 1;51(5):e106-e114. [CrossRef]

- Cusinato M, Sivayoham N, Planche T. Sensitivity and specificity of monocyte distribution width (MDW) in detecting patients with infection and sepsis in patients on sepsis pathway in the emergency department. Infection. 2023 Jun;51(3):715-727. [CrossRef]

- Reinhart K, Bauer M, Riedemann NC, Hartog CS. New approaches to sepsis: molecular diagnostics and biomarkers. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012 Oct;25(4):609-34. [CrossRef]

- Klein Klouwenberg PM, Cremer OL, van Vught LA, Ong DS, Frencken JF, Schultz MJ, Bonten MJ, van der Poll T. Likelihood of infection in patients with presumed sepsis at the time of intensive care unit admission: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2015 Sep 7;19(1):319. [CrossRef]

- Marshall JC. Why have clinical trials in sepsis failed? Trends Mol Med 2014; 20:195–203.

- Meyer NJ, Prescott HC. Sepsis and Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2024 Dec 5;391(22):2133-2146.

- Gibbs AAM, Laupland KB, Edwards F, et al. Trends in Enterobacterales bloodstream infections in children. Pediatrics 2024;154. [CrossRef]

- C.J. Murray, K.S. Ikuta, F. Sharara, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis Lancet, 399 (2022) . [CrossRef]

- U. Okomo, E.N.K. Akpalu, K. Le Doare, et al. Aetiology of invasive bacterial infection and antimicrobial resistance in neonates in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis in line with the STROBE-NI reporting guidelines Lancet Infect Dis, 19 (2019), pp. 1219-1234 . [CrossRef]

- L.Y. Leung, H.L. Huang, K.K. Hung, et al. Door-to-antibiotic time and mortality in patients with sepsis: Systematic review and meta-analysis Eur J Intern Med, 129 (2024), pp. 48-61. [CrossRef]

- Ligi D, Lo Sasso B, Della Franca C, Giglio RV, Agnello L, Ciaccio M, Mannello F. Monocyte distribution width alterations and cytokine storm are modulated by circulating histones. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2023 Feb 28;61(8):1525-1535. [CrossRef]

- Ligi D, Giglio RV, Henry BM, Lippi G, Ciaccio M, Plebani M, Mannello F. What is the impact of circulating histones in COVID-19: a systematic review. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2022 Jul 19;60(10):1506-1517. [CrossRef]

- Ligi D, Lo Sasso B, Giglio RV, Maniscalco R, DellaFranca C, Agnello L, et al. Circulating histones contribute to monocyte and MDW alterations as common mediators in classical and COVID-19 sepsis. Crit Care 2022;26:260. [CrossRef]

| Patient’s characteristics | |||||||

| All [N. 608] | Female [N. 235] | Male [N. 373] | |||||

| Variables | Mean | ±SD | Mean | ±SD | Mean | ±SD | P value |

| Age (years) | 70,9 | ±13,87 | 72,46 | ±12,87 | 70,02 | ±14,39 | NS |

| GFR_CKD_EPI (mL/min/1,73) | 58,04 | ±29,60 | 54,08 | ±29,41 | 60,60 | ±29,48 | <0,05 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1,57 | ±1,42 | 1,46 | ±1,25 | 1,64 | ±1,52 | <0,05 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1,09 | ±2,19 | 1,10 | ±2,37 | 1,09 | ±2,07 | NS |

| Procalcitonin (PCT) (ng/mL) | 12,7 | ±39,22 | 11,08 | ±35,27 | 13,82 | ±41,57 | NS |

| Reactive C protein (PCR) (mg/dL) | 11,4 | ±9,98 | 11,32 | ±9,89 | 11,44 | ±10,06 | NS |

| MDW | 23,7 | ±6,5 | 23,77 | ±5,85 | 23,60 | ±6,95 | NS |

| WBC (109/L) | 12,91 | ±8,46 | 14,06 | ±8,02 | 12,19 | ±8,65 | <0,05 |

| RBC (1012/L) | 3,72 | ±0,775 | 3,63 | ±0,72 | 3,78 | ±0,80 | <0,05 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 11,0 | ±2,2 | 10,57 | ±1,88 | 11,27 | ±2,27 | <0,05 |

| Neutrophiles (109/L) | 10,8 | ±6,98 | 11,86 | ±7,38 | 10,14 | ±6,63 | <0,05 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) | 1,09 | ±1,67 | 1,18 | ±1,81 | 1,035 | ±1,57 | <0,05 |

| Basophiles (109/L) | 0,023 | ±0,04 | 0,03 | ±0,043 | 0,02 | ±0,029 | <0,05 |

| Eosinophiles (109/L) | 0,07 | ±0,25 | 0,103 | ±0,37 | 0,047 | ±0,114 | <0,05 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 207,4 | ±114,3 | 225,6 | ±121,6 | 196,1 | ±108,2 | <0,05 |

| MPV (fL) | 9,8 | ±1,60 | 9,985 | ±1,63 | 9,74 | ±1,57 | NS |

| Monocytes (109/L) | 0,93 | ±4,01 | 0,86 | ±1,27 | 0,97 | ±5,02 | <0,05 |

| Infection | |||||||||

| No infection [# 196] | BSIs [# 177] |

Localized infection [# 235] |

No infection vs BSIs | No infection vs Localized infection | BSIs vs Localized infection |

||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P | P | P | |

| Age (years) | 69,38 | 15,46 | 72,44 | 11,88 | 71,17 | 13,77 | NS | NS | NS |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1,28 | 1,15 | 1,70 | 1,39 | 1,70 | 1,60 | 0,0001 | 0,0024 | NS |

| MDW | 19,44 | 3,49 | 27,10 | 5,93 | 24,60 | 7,04 | <0,0001 | <0,0001 | 0,0002 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 3,11 | 15,32 | 24,74 | 57,14 | 11,31 | 32,96 | <0,0001 | 0,002 | 0,0033 |

| PCR (mg/dL) | 6,48 | 7,63 | 15,60 | 10,33 | 12,12 | 9,73 | <0,0001 | <0,0001 | 0,0006 |

| Erythrocytes (1012/L) | 3,93 | 0,75 | 3,62 | 0,74 | 3,62 | 0,78 | <0,0001 | <0,0001 | NS |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 11,63 | 2,06 | 10,77 | 2,05 | 10,65 | 2,20 | <0,0001 | <0,0001 | NS |

| Haematocrit (%) | 35,04 | 6,40 | 32,50 | 6,50 | 32,19 | 6,66 | <0,0001 | <0,0001 | NS |

| Leukocytes (109/L) | 12,11 | 4,80 | 13,65 | 11,67 | 13,03 | 7,92 | NS | NS | NS |

| Neutrophils (109/L) | 10,03 | 4,38 | 11,27 | 8,43 | 11,10 | 7,49 | NS | NS | NS |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) | 1,22 | 1,92 | 1,08 | 2,20 | 0,99 | 0,69 | <0,0001 | NS | NS |

| Basophil (109/L) | 0,02 | 0,03 | 0,02 | 0,04 | 0,03 | 0,04 | 0,0242 | NS | NS |

| Eosinophils (109/L) | 0,05 | 0,10 | 0,04 | 0,10 | 0,11 | 0,38 | NS | 0,0276 | 0,0329 |

| Monocytes (109/L) | 0,81 | 0,54 | 1,21 | 7,28 | 0,82 | 1,21 | <0,0001 | NS | NS |

| Platelets (109/L) | 217,75 | 92,59 | 189,21 | 111,19 | 211,82 | 131,12 | 0,0002 | NS | NS |

| MPV (fL) | 9,52 | 1,439 | 9,83 | 1,74 | 10,11 | 1,57 | NS | 0,0001 | NS |

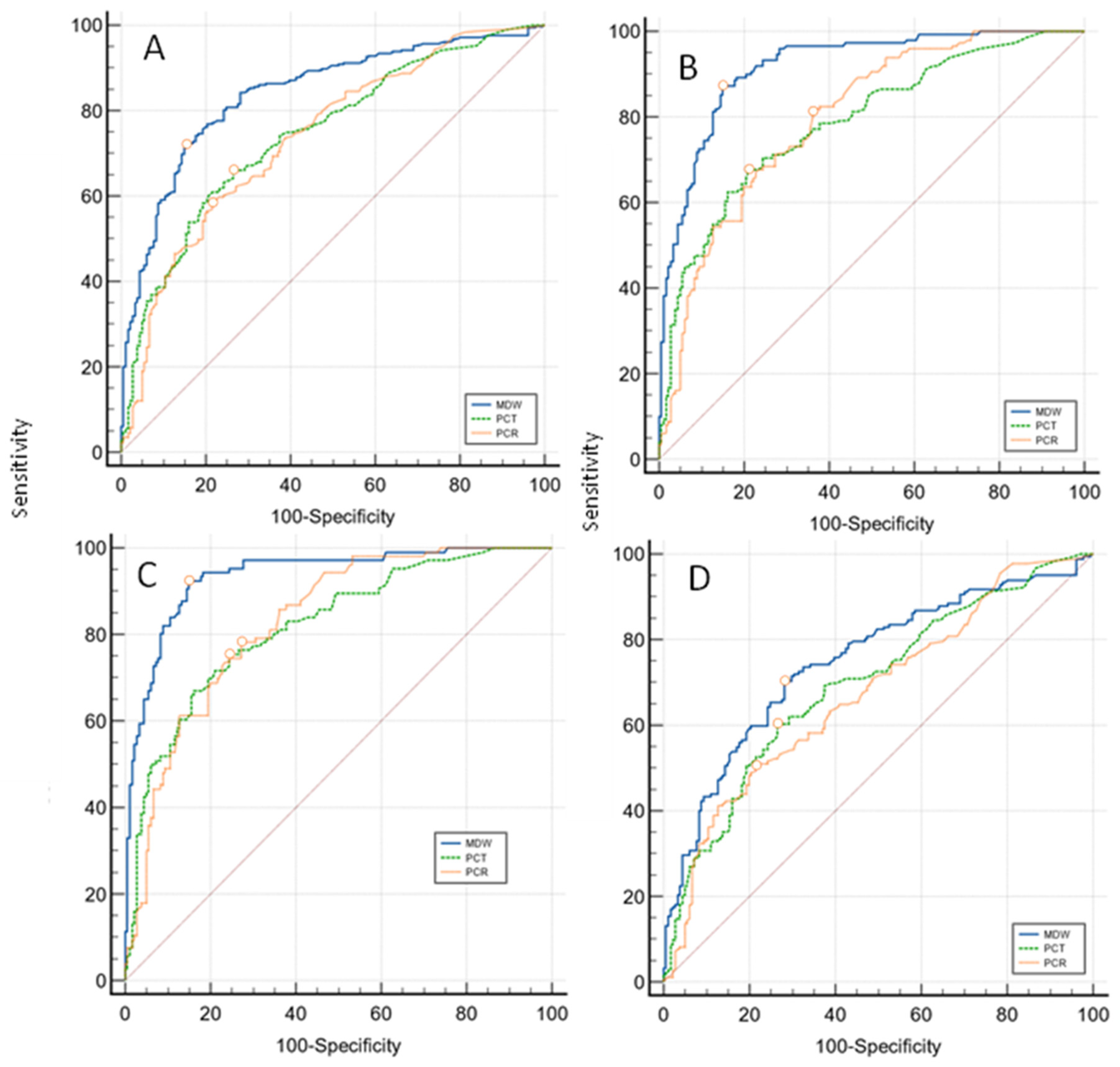

| Overall infections 412 vs No infection 196 Sample size 608 | ||||||

| Variable | AUC | SE | 95% CI | Difference between areas |

95% CI |

Significance level |

| MDW | 0,840 | 0,0173 | 0,808 to 0,869 | 0,095 (MDW vs PCT) | 0,0542 to 0,135 | P < 0,0001 |

| PCT | 0,746 | 0,0213 | 0,708 to 0,781 | 0,103 (MDW vs PCR) | 0,0628 to 0,143 | P < 0,0001 |

| PCR | 0,737 | 0,0222 | 0,699 to 0,773 | 0,00825 (PCR vs PCT) | -0,0363 to 0,0528 | P = NS |

| Localized infections 235 vs No infection 196 Sample size 431 | ||||||

| MDW | 0,748 | 0,0258 | 0,700 to 0,792 | 0,0533 (MDW vs PCT) | -0,001 to 0,108 | P = NS |

| PCT | 0,695 | 0,0275 | 0,645 to 0,742 | 0,0737 (MDW vs PCR) | 0,0230 to 0,124 | P = 0,0044 |

| PCR | 0,675 | 0,0280 | 0,624 to 0,723 | 0,0203 (PCR vs PCT) | -0,0368 to 0,0774 | P = NS |

| BSIs 177 vs No infection 196 Sample size 373 | ||||||

| MDW | 0,918 | 0,0150 | 0,883 to 0,945 | 0,13 (MDW vs PCT) | 0,0842 to 0,176 | P < 0,0001 |

| PCT | 0,788 | 0,0251 | 0,740 to 0,831 | 0,12 (MDW vs PCR) | 0,0758 to 0,164 | P < 0,0001 |

| PCR | 0,798 | 0,0240 | 0,751 to 0,840 | 0,010 (PCR vs PCT) | -0,0405 to 0,0612 | P = NS |

| BSIs, SARS-COV-2 excluded 134 vs No infection 196 Sample size 330 | ||||||

| MDW | 0,936 | 0,0148 | 0,901 to 0,961 | 0,118 (MDW vs PCT) | 0,0706 to 0,164 | P < 0,0001 |

| PCT | 0,818 | 0,0258 | 0,769 to 0,861 | 0,107 (MDW vs PCR) | 0,0624 to 0,151 | P < 0,0001 |

| PCR | 0,829 | 0,0238 | 0,781 to 0,871 | 0,011 (PCR vs PCT) | -0,0404 to 0,0622 | P = NS |

| MDW Criterion | Sensitivity | 95% CI | Specificity | 95% CI | +LR | 95% CI | -LR | 95% CI | +PV | -PV | |

| Overall infections | >20,43 | 72,45 | 65,6 - 78,6 | 84,15 | 80,2 - 87,5 | 3,05 | 2,42 - 3,85 | 0,22 | 0,17 - 0,28 | 86,5 | 68,6 |

| BSIs | >21,96 | 86,84 | 80,4 - 91,8 | 85,05 | 79,2 - 89,8 | 5,81 | 4,13 - 8,17 | 0,15 | 0,10 - 0,23 | 82 | 89,2 |

| Localised infections | >20,43 | 70,37 | 63,3 - 76,8 | 72,45 | 65,6 - 78,6 | 2,55 | 2,00 - 3,26 | 0,41 | 0,32 - 0,52 | 71,1 | 71,7 |

| BSIs excluded COVID19 | >21,96 | 91,59 | 84,6 - 96,1 | 85,05 | 79,2 - 89,8 | 6,13 | 4,36 - 8,61 | 0,099 | 0,053 - 0,19 | 77,2 | 94,8 |

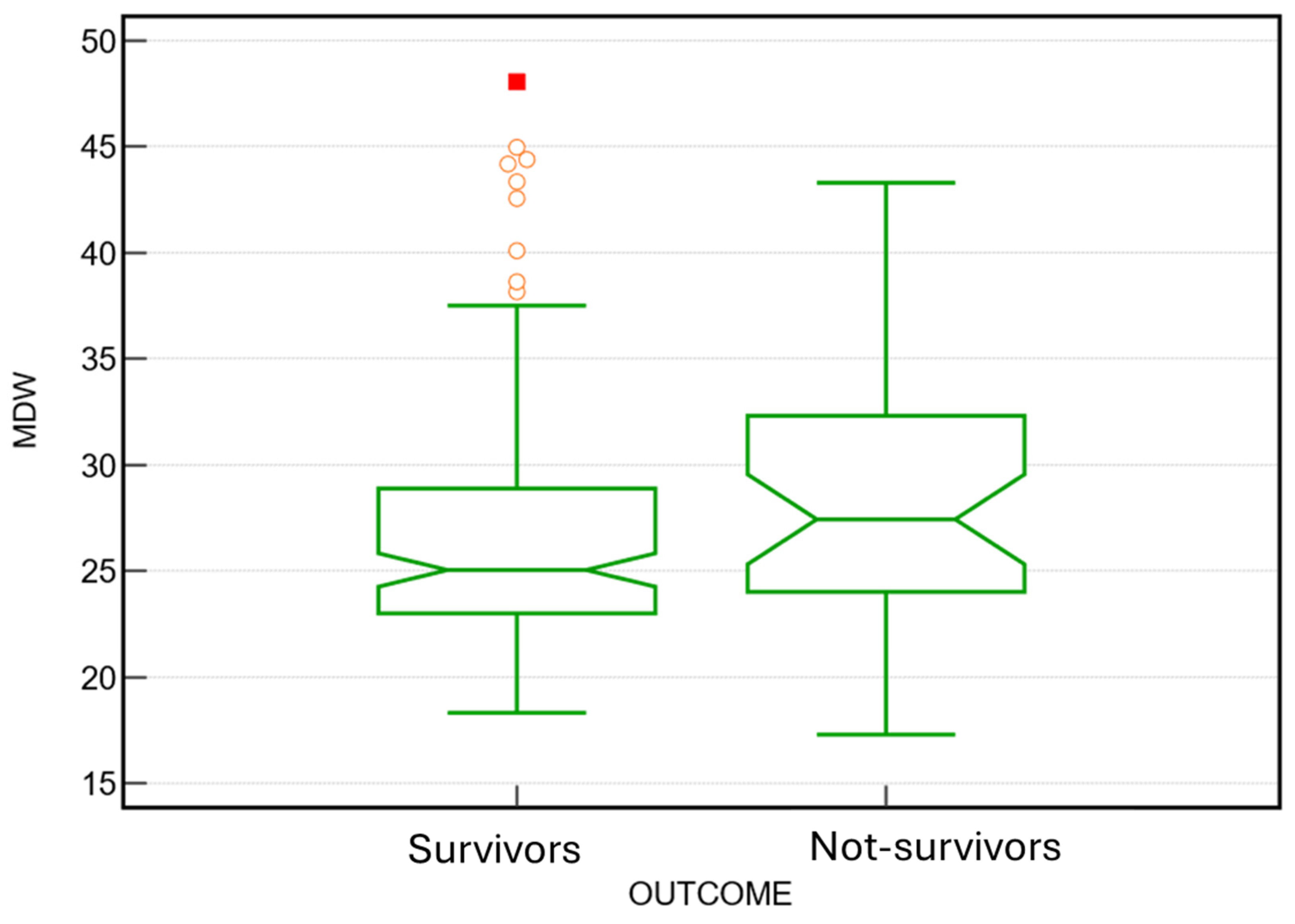

| Parameters | Outcome | N | Mean | ±SD. | SE | P value |

| MDW | not-survivors | 110 | 25,51 | 6,19 | 0,59 |

0.001 |

| survivors | 498 | 23,26 | 6,55 | 0,29 | ||

| PCT | not-survivors | 110 | 13,9 | 38,07 | 3,65 |

NS |

| survivors | 498 | 12,5 | 39,51 | 1,81 | ||

| PCR | not-survivors | 110 | 12,8 | 9,48 | 0,91 |

NS |

| survivors | 498 | 11,08 | 10,07 | 0,46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).