Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

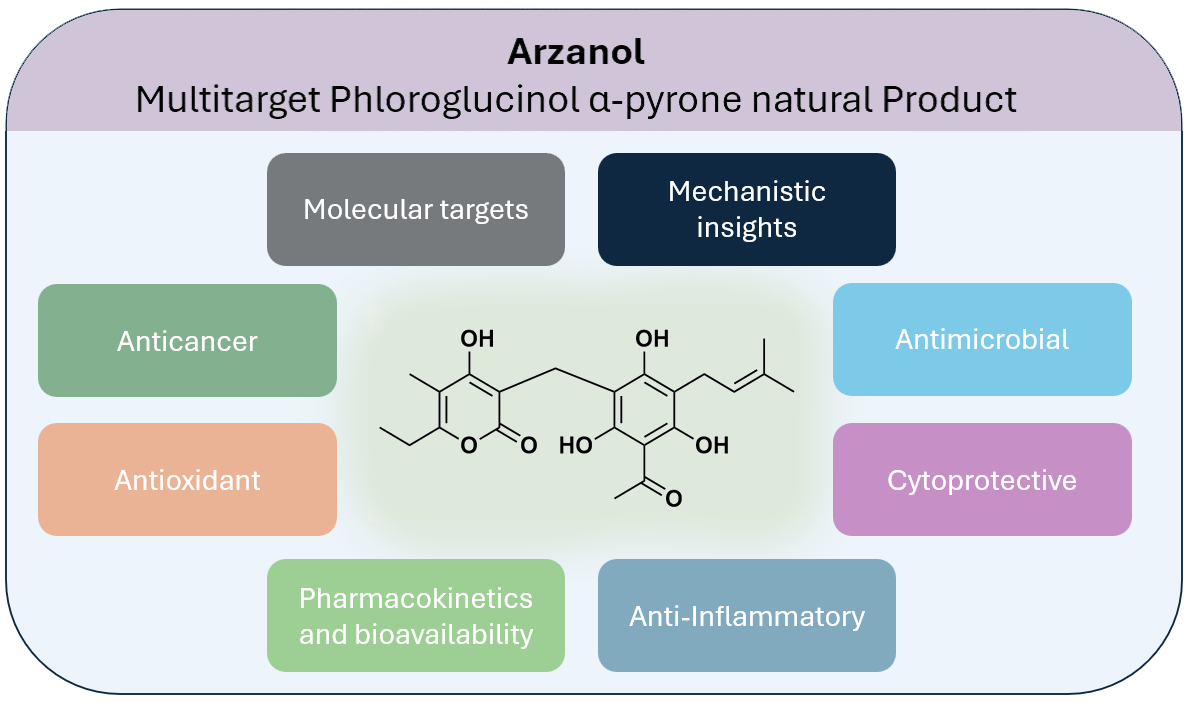

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Search Methodology

2. Isolation, Natural Sources and Synthesis

2.1. Synthetic Derivatives

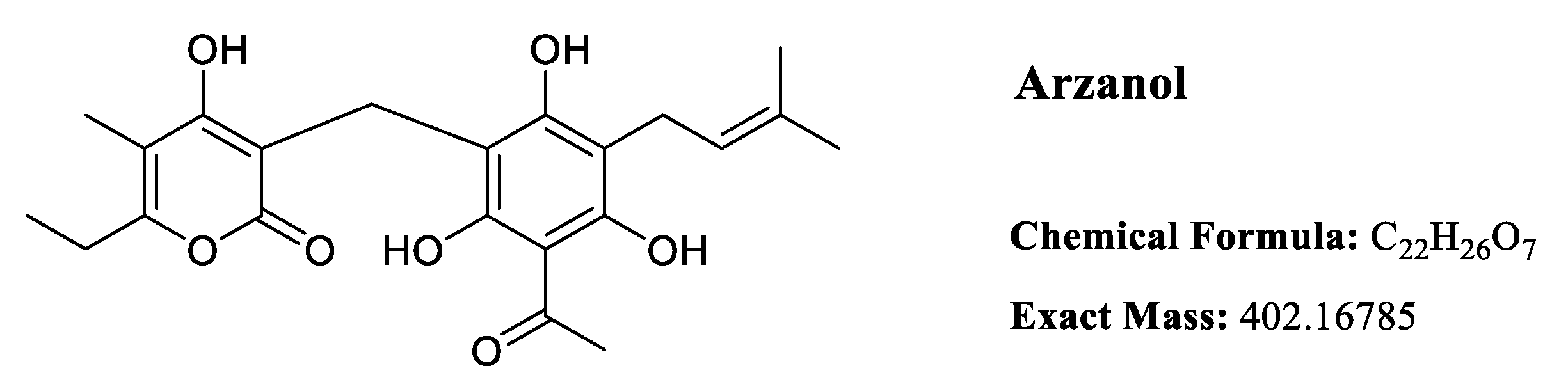

3. Chemical Structure and Properties

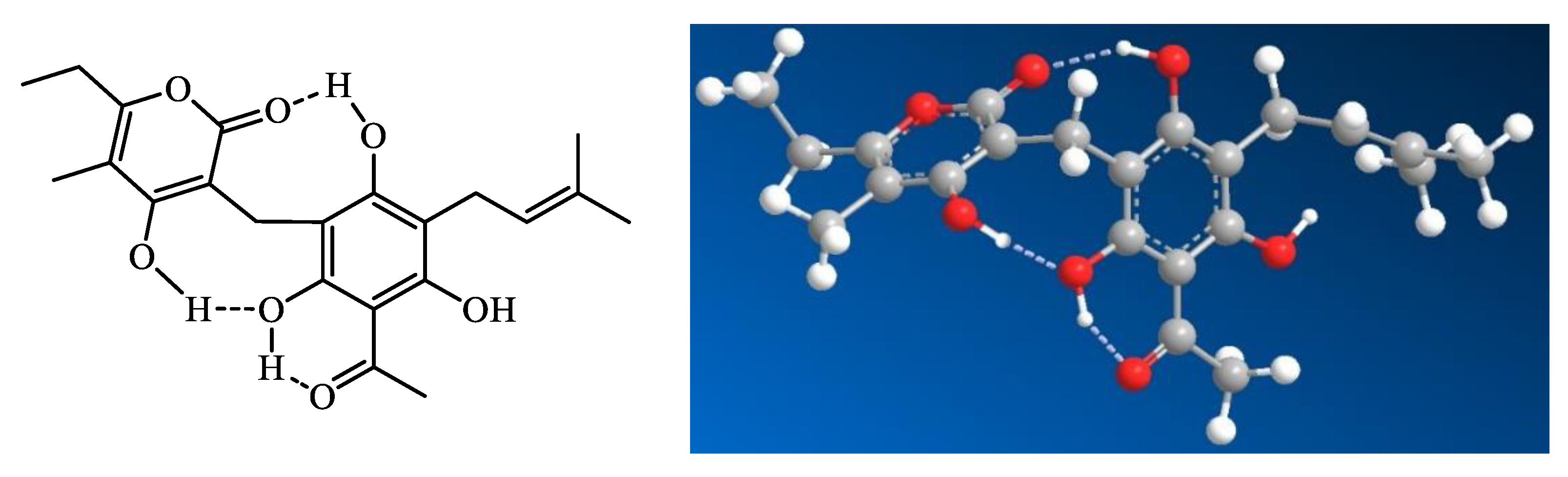

3.1. Conformational Dynamics and Solution Structure

4. Anti-inflammatory Activity

4.1. NF-κB Pathway Inhibition

4.2. Dual Enzymatic Inhibition

4.3. In vivo Validation

5. Antioxidant Activity

5.1. Protection Against Lipid Peroxidation in Lipoproteins

5.2. Mechanistic Insights into Antioxidant Action

5.3. Cellular Cytoprotection Against Oxidative Stress

5.3.1. Protection of Skin Cells

5.3.2. Neuroprotection Against Oxidative Stress

5.4. In vivo Antioxidant Effects

6. Antimicrobial Activity

7. Molecular Targets and Mechanisms

7.1. Brain Glycogen Phosphorylase

7.2. Autophagy Modulation and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

7.3. SIRT1 Inhibition and Metabolic Regulation

8. Pharmacokinetics and Bioavailability

8.1. Gastrointestinal Stability

8.2. Intestinal Absorption and Cellular Transport

8.3. Serum Protein Binding and the Bi-Directional Implications for Activity and Delivery

8.4. Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration

9. Neurobehavioral and Metabolic Effects through SIRT1 inhibition

10. Cytotoxicity Profile and Selectivity

11. Prospects for Drug Development

Conclusion

| Category | Subcategory | Biological Activity | IC50/EC50/Dose | Model/Cell Type | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-inflammatory | NF-κB Pathway | Switches off NF-κB in Jurkat immune-cell assay | IC50 ~5 µg/mL (≈12 µM) | Jurkat cells | [1] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Cytokine Inhibition | IL-1β reduction | IC50 5.6 µM | LPS-stimulated human monocytes | [1] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Cytokine Inhibition | TNF-α reduction | IC50 9.2 µM | LPS-stimulated human monocytes | [1] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Cytokine Inhibition | IL-6 reduction | IC50 13.3 µM | LPS-stimulated human monocytes | [1] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Cytokine Inhibition | IL-8 reduction | IC50 21.8 µM | LPS-stimulated human monocytes | [1] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | PGE₂ reduction | IC50 18.7 µM | LPS-stimulated human monocytes | [1] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | 5-LOX inhibition | IC50 3.1 µM | Recombinant enzyme assay | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | 5-LOX inhibition in neutrophils (A23187/AA stimulation) | IC50 2.9 µM | Human neutrophils | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | 5-LOX inhibition in neutrophils (LPS/fMLP stimulation) | IC50 8.1 µM | Human neutrophils | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | mPGES-1 inhibition | IC50 0.4 µM | IL-1β-stimulated A549 cells | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | COX-1 inhibition (12-HHT reduction) | IC50 2.3 µM | Human platelets | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | COX-1 inhibition (TXB₂ reduction) | IC50 2.9 µM | Human platelets | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Eicosanoid Pathway | PGE₂ reduction in whole blood | ~50% at 30 µM | Human whole blood | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Invivo | Reduces pleural fluid volume | 59% at 3.6 mg/kg | Rat pleurisy model | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Invivo | Reduces inflammatory cell infiltration | 48% at 3.6 mg/kg | Rat pleurisy model | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Invivo | Reduces PGE₂ levels | 47% at 3.6 mg/kg | Rat pleurisy model | [2] |

| Anti-inflammatory | Invivo | Reduces LTB₄ levels | 31% at 3.6 mg/kg | Rat pleurisy model | [2] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Lipid Protection | Complete inhibition of linoleic acid autoxidation | IA50 1.2 nmol | Solvent-free film (37°C, 32h) | [3] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Lipid Protection | Protection under EDTA-mediated oxidation | ≥80% at 1 nmol, 100% at ≥2.5 nmol | Linoleic acid + EDTA | [3] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Lipid Protection | Protection in FeCl₃-catalyzed oxidation | 13% at 40 nmol, 80% at 80 nmol | Linoleic acid + FeCl₃ | [3] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cholesterol Protection | Complete protection against cholesterol oxidation | 100% at 10 nmol | 140°C thermal oxidation | [3] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cholesterol Protection | Prevention of 7-keto and 7β-OH formation | IA50 5.6-6.8 nmol | 140°C, 1-2h | [4] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | LDL Protection | Protects LDL from Cu²⁺-induced oxidation | Significant from 8 µM | Human LDL (37°C, 2h) | [26] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Liposome Protection | Protection of polyunsaturated fatty acids | 89.1% at 10 µM | Phospholipid liposomes + Cu²⁺ | [4] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cell Protection | No cytotoxicity to VERO cells | Up to 40 µM | VERO fibroblasts | [3] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cell Protection | Reduces lipid peroxidation in VERO cells | 40% reduction at 7.5 µM | VERO cells + 750 µM TBH | [3] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cell Protection | No cytotoxicity to VERO cells | Up to 50 µM | VERO cells (24h) | [26] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cell Protection | No cytotoxicity to differentiated Caco-2 | Up to 100 µM | Differentiated Caco-2 (24h) | [26] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cell Protection | Protects VERO cells from TBH | Significant at 25-50 µM | VERO cells + TBH | [26] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Cell Protection | Protects Caco-2 cells from TBH | Significant from 25 µM | Differentiated Caco-2 + TBH | [26] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Invivo | Prevents plasma lipid consumption | 9 mg/kg i.p. | Wistar rats + Fe-NTA | [4] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Invivo | Protects plasma unsaturated fatty acids | Complete at 9 mg/kg | Wistar rats + Fe-NTA | [4] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Invivo | Reduces plasma MDA levels | 9 mg/kg | Wistar rats + Fe-NTA | [4] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Invivo | Reduces plasma 7-ketocholesterol | 9 mg/kg | Wistar rats + Fe-NTA | [4] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Keratinocyte Protection | No cytotoxicity | 5-100 µM | HaCaT cells | [12] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Keratinocyte Protection | Protects against H₂O₂ cytotoxicity | 50 µM pre-treatment | HaCaT cells + 2.5-5 mM H₂O₂ | [12] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Keratinocyte Protection | Reduces ROS generation | 50 µM | HaCaT cells + 0.5-5 mM H₂O₂ | [12] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Keratinocyte Protection | Prevents lipid peroxidation | 50 µM | HaCaT cells + 2.5-5 mM H₂O₂ | [12] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Keratinocyte Protection | Prevents apoptosis (caspase-3/7) | 50 µM | HaCaT cells + 5 mM H₂O₂ | [12] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Keratinocyte Protection | Preserves mitochondrial membrane potential | 50 µM | HaCaT cells + 5 mM H₂O₂ | [12] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Increases viability (differentiated cells) | 5-25 µM | Differentiated SH-SY5Y | [13] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Cytotoxic at high dose (differentiated cells) | 71% reduction at 100 µM | Differentiated SH-SY5Y | [13] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Non-toxic (undifferentiated cells) | 2.5-100 µM | Undifferentiated SH-SY5Y | [13] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Protects differentiated cells from H₂O₂ | 5-25 µM | Differentiated SH-SY5Y + 0.5 mM H₂O₂ | [13] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Protects undifferentiated cells from H₂O₂ | 5 µM | Undifferentiated SH-SY5Y + 0.5 mM H₂O₂ | [13] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Reduces ROS (differentiated cells) | 5-25 µM | Differentiated SH-SY5Y + H₂O₂ | [13] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Reduces ROS (undifferentiated cells) | 5 µM | Undifferentiated SH-SY5Y + H₂O₂ | [13] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Decreases basal apoptosis | 5-25 µM | Differentiated SH-SY5Y | [13] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Protects from H₂O₂-induced apoptosis (PI assay) | 10-25 µM | ifferentiated SH-SY5Y + 0.25 mM H₂O₂ | [13] |

| Antioxidant/Cytoprotective | Neuronal Protection | Protects from H₂O₂-induced apoptosis (caspase) | 10-25 µM | Differentiated SH-SY5Y + 0.25 mM H₂O₂ | [13] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | Neuroprotection | Protects from glutamate toxicity | 5-10 µM | SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | Metabolic Effects | Attenuates weight gain (no effect on food intake) | 100 mg/kg, 3 weeks oral | Mice | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | Behavioral Effects | Anxiolytic effect (comparable to diazepam) | 100 mg/kg | Mice | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | Behavioral Effects | Antidepressant effect (comparable to amitriptyline) | 100 mg/kg | Mice | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | Behavioral Effects | No locomotor or memory impairment | 100 mg/kg | Mice | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | SIRT1 Modulation | Binds SIRT1 via 4 H-bonds | Molecular docking | insilico | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | SIRT1 Modulation | SIRT1 inhibition | 10-100 µM | Cell-free assay | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | SIRT1 Modulation | Reduces SIRT1 expression/activity | 100 mg/kg HSE or 10 µM | Mouse hippocampus (ex vivo) | [9] |

| Neuroprotective/Neurobehavioral | SIRT1 Modulation | Suppresses FoxO1 signaling | 100 mg/kg HSE or 10 µM | Cell and tissue studies | [9] |

| Anticancer | Autophagy Modulation | Inhibits starvation-induced autophagy | +164.6% mCitrine-LC3 | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts | [11] |

| Anticancer | Autophagy Modulation | Accumulates LC3-II and p62/SQSTM1 | Not specified | HeLa cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Autophagy Modulation | Increases but reduces size of autophagosomes | Not specified | HeLa cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Autophagy Modulation | Increases ATG16L1-positive structures | Not specified | HeLa cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | Cytotoxic to cisplatin-sensitive bladder cancer | IC50 6.6 µM | RT-112 cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | Cytotoxic to cisplatin-resistant bladder cancer | IC50 9.6 µM | RT-112 cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | Cytotoxic to undifferentiated Caco-2 | 55% reduction at 100 µM | Undifferentiated Caco-2 | [4] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | Cytotoxic to HeLa cells | 36% reduction at 200 µg/mL | HeLa cells (24h) | [4] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | Cytotoxic to B16F10 cells | 95% reduction at 200 µg/mL | B16F10 melanoma (24h) | [4] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | No cytotoxicity to differentiated Caco-2 | Up to 100 µM | Differentiated Caco-2 | [4] |

| Anticancer | Direct Cytotoxicity | No cytotoxicity to L5178Y cells | 20 µg/mL | Murine lymphoma L5178Y | [6] |

| Anticancer | Chemosensitization | Enhances cisplatin effect | Reduces IC50 from 22.5 to 7.1 µM | RT-112 cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Mitochondrial Effects | Induces mitochondrial fragmentation | Not specified | HeLa cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Mitochondrial Effects | Reduces basal/maximal respiration | Not specified | HeLa cells | [11] |

| Anticancer | Mitochondrial Effects | Inhibits OXPHOS complexes II, III, V | Not specified | Isolated mitochondria | [11] |

| Anticancer | Mitochondrial Effects | Inhibits NQO1 | Significant at 10 µM | Direct activity assay | [11] |

| Metabolic | Glycogen Metabolism | Binds brain Glycogen Phosphorylase (bGP) | Identified as main target | HeLa cell lysates | [10] |

| Metabolic | Glycogen Metabolism | Direct bGP binding (DARTS confirmed) | Dose-dependent protection | DARTS assay | [10] |

| Metabolic | Glycogen Metabolism | Binds at AMP allosteric site | Competitive with AMP | Competitive binding assay | [10] |

| Metabolic | Glycogen Metabolism | High-affinity bGP binding | Kd = 0.32 ± 0.15 µM | Surface Plasmon Resonance | [10] |

| Metabolic | Glycogen Metabolism | Predicted AMP site binding | Kd,pred = 0.65 ± 0.18 µM | Molecular docking | [10] |

| Metabolic | Glycogen Metabolism | Activates bGP enzyme | Dose-dependent activation | HeLa cell lysates | [10] |

| Antibacterial | S. aureus (drug-resistant) | SA1199B (NorA efflux) inhibition | MIC 1 µg/mL | S. aureus SA1199B | [5] |

| Antibacterial | S. aureus (drug-resistant) | XU212 (TetK) inhibition | MIC 4 µg/mL | S. aureus XU212 | [5] |

| Antibacterial | S. aureus (drug-resistant) | ATCC 25923 (reference) inhibition | MIC 1 µg/mL | S. aureus ATCC 25923, Mueller-Hinton/MTT method | [5] |

| Antibacterial | S. aureus (drug-resistant) | RN4220 (MsrA) inhibition | MIC 2 µg/mL | S. aureus RN4220 | [5] |

| Antibacterial | S. aureus (drug-resistant) | EMRSA-15 (epidemic MRSA) inhibition | MIC 4 µg/mL | S. aureus EMRSA-15 | [5] |

| Antibacterial | S. aureus (drug-resistant) | EMRSA-16 (epidemic MRSA) inhibition | MIC 2 µg/mL | S. aureus EMRSA-16 | [5] |

| Antibacterial | Negative Results | No activity against S. aureus ATCC 25923 | No inhibition at 20 µg/mL | S. aureus ATCC 25923, CLSI broth microdilution | [6] |

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Appendino, G.; Ottino, M.; Marquez, N.; Bianchi, F.; Giana, A.; Ballero, M.; Sterner, O.; Fiebich, B.L.; Munoz, E. Arzanol, an anti-inflammatory and anti-HIV-1 phloroglucinol α-pyrone from Helichrysum italicum ssp. microphyllum. Journal of natural products 2007, 70, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Koeberle, A.; Dehm, F.; Pollastro, F.; Appendino, G.; Northoff, H.; Rossi, A.; Sautebin, L.; Werz, O. Arzanol, a prenylated heterodimeric phloroglucinyl pyrone, inhibits eicosanoid biosynthesis and exhibits anti-inflammatory efficacy in vivo. Biochemical pharmacology 2011, 81, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, A.; Deiana, M.; Atzeri, A.; Corona, G.; Incani, A.; Melis, M.P.; Appendino, G.; Dessì, M.A. Evaluation of the antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of arzanol, a prenylated α-pyrone–phloroglucinol etherodimer from Helichrysum italicum subsp. microphyllum. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2007, 165, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Atzeri, A.; Nieddu, M.; Appendino, G. New insights into the antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity of arzanol and effect of methylation on its biological properties. Chemistry and physics of lipids 2017, 205, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Pollastro, F.; Chianese, G.; Minassi, A.; Gibbons, S.; Arunotayanun, W.; Mabebie, B.; Ballero, M.; Appendino, G. Antimicrobial phenolics and unusual glycerides from Helichrysum italicum subsp. microphyllum. Journal of natural products 2013, 76, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.; Ebrahim, W.; Özkaya, F.C.; Mándi, A.; Kurtán, T.; El-Neketi, M.; Liu, Z.; Proksch, P. Pyrone derivatives from Helichrysum italicum. Fitoterapia 2019, 133, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Abrosca, B.; Buommino, E.; Caputo, P.; Scognamiglio, M.; Chambery, A.; Donnarumma, G.; Fiorentino, A. Phytochemical study of Helichrysum italicum (Roth) G. Don: Spectroscopic elucidation of unusual amino-phlorogucinols and antimicrobial assessment of secondary metabolites from medium-polar extract. Phytochemistry 2016, 132, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaberi, M.; Danton, O.; Tayarani-Najaran, Z.; Asili, J.; Iranshahi, M.; Emami, S.A.; Hamburger, M. HPLC-Based Activity Profiling for Antiprotozoal Compounds in the Endemic Iranian Medicinal Plant Helichrysum oocephalum. Journal of Natural Products 2019, 82, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonetti, V.; Caroli, C.; Governa, P.; Virginia, B.; Pollastro, F.; Franchini, S.; Manetti, F.; Les, F.; López, V.; Pellati, F.; Galeotti, N. Helichrysum stoechas (L.) Moench reduces body weight gain and modulates mood disorders via inhibition of silent information regulator 1 (SIRT1) by arzanol. Phytotherapy Research 2023, 37, 4304–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Gaudio, F.; Pollastro, F.; Mozzicafreddo, M.; Riccio, R.; Minassi, A.; Monti, M.C. Chemoproteomic fishing identifies arzanol as a positive modulator of brain glycogen phosphorylase. Chemical Communications 2018, 54, 12863–12866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitersen, J.; Berning, L.; Stuhldreier, F.; Ceccacci, S.; Schlütermann, D.; Friedrich, A.; Wu, W.; Sun, Y.; Böhler, P.; Berleth, N. High-throughput screening for natural compound-based autophagy modulators reveals novel chemotherapeutic mode of action for arzanol. Cell Death & Disease 2021, 12, 560. [Google Scholar]

- Piras, F.; Sogos, V.; Pollastro, F.; Appendino, G.; Rosa, A. Arzanol, a natural phloroglucinol α-pyrone, protects HaCaT keratinocytes against H2O2-induced oxidative stress, counteracting cytotoxicity, reactive oxygen species generation, apoptosis, and mitochondrial depolarization. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2024, 44, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, F.; Sogos, V.; Pollastro, F.; Rosa, A. Protective effect of arzanol against H2O2-induced oxidative stress damage in differentiated and undifferentiated SH-SY5Y Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 7386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Les, F.; Venditti, A.; Cásedas, G.; Frezza, C.; Guiso, M.; Sciubba, F.; Serafini, M.; Bianco, A.; Valero, M.S.; López, V. Everlasting flower (Helichrysum stoechas Moench) as a potential source of bioactive molecules with antiproliferative, antioxidant, antidiabetic and neuroprotective properties. Industrial crops and products 2017, 108, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minassi, A.; Cicione, L.; Koeberle, A.; Bauer, J.; Laufer, S.; Werz, O.; Appendino, G. A Multicomponent Carba-Betti Strategy to Alkylidene Heterodimers–Total Synthesis and Structure–Activity Relationships of Arzanol. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastrelli, F.; Bagno, A.; Appendino, G.; Minassi, A. Bioactive Phloroglucinyl Heterodimers: The Tautomeric and Rotameric Equlibria of Arzanol. European Journal of Organic Chemistry 2016, 2016, 4810–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wu, M.; Huang, S.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Z. Targeting microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 to develop drugs treating the inflammatory diseases. American Journal of Translational Research 2021, 13, 391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iranshahi, M.; Chini, M.G.; Masullo, M.; Sahebkar, A.; Javidnia, A.; Chitsazian Yazdi, M.; Pergola, C.; Koeberle, A.; Werz, O.; Pizza, C. Can small chemical modifications of natural pan-inhibitors modulate the biological selectivity? The case of curcumin prenylated derivatives acting as HDAC or mPGES-1 inhibitors. Journal of Natural Products 2015, 78, 2867–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeberle, A.; Northoff, H.; Werz, O. Curcumin blocks prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis through direct inhibition of the microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2009, 8, 2348–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoff, M.; Seitz, S.; Paul, M.; Noha, S.M.; Jauch, J.; Schuster, D.; Werz, O. Tetra-and pentacyclic triterpene acids from the ancient anti-inflammatory remedy frankincense as inhibitors of microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1. Journal of Natural Products 2014, 77, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Rowland, S.E.; Clark, P.; Giroux, A.; Côté, B.; Guiral, S.; Salem, M.; Ducharme, Y.; Friesen, R.W.; Methot, N. MF63 [2-(6-chloro-1 H-phenanthro [9, 10-d] imidazol-2-yl)-isophthalonitrile], a selective microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 inhibitor, relieves pyresis and pain in preclinical models of inflammation. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 2008, 326, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, K.; Steinmetz, J.; Bergqvist, F.; Arefin, S.; Spahiu, L.; Wannberg, J.; Pawelzik, S.C.; Morgenstern, R.; Stenberg, P.; Kublickiene, K.; et al. Biological characterization of new inhibitors of microsomal PGE synthase-1 in preclinical models of inflammation and vascular tone. Br J Pharmacol 2019, 176, 4625–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkby, N.S.; Raouf, J.; Ahmetaj-Shala, B.; Liu, B.; Mazi, S.I.; Edin, M.L.; Chambers, M.G.; Korotkova, M.; Wang, X.; Wahli, W.; et al. Mechanistic definition of the cardiovascular mPGES-1/COX-2/ADMA axis. Cardiovasc Res 2020, 116, 1972–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svouraki, A.; Garscha, U.; Kouloura, E.; Pace, S.; Pergola, C.; Krauth, V.; Rossi, A.; Sautebin, L.; Halabalaki, M.; Werz, O. Evaluation of dual 5-lipoxygenase/microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1 inhibitory effect of natural and synthetic acronychia-type isoprenylated acetophenones. Journal of Natural Products 2017, 80, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawelzik, S.-C.; Uda, N.R.; Spahiu, L.; Jegerschöld, C.; Stenberg, P.; Hebert, H.; Morgenstern, R.; Jakobsson, P.-J. Identification of Key Residues Determining Species Differences in Inhibitor Binding of Microsomal Prostaglandin E Synthase-1*[S]. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 29254–29261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Pollastro, F.; Atzeri, A.; Appendino, G.; Melis, M.P.; Deiana, M.; Incani, A.; Loru, D.; Dessì, M.A. Protective role of arzanol against lipid peroxidation in biological systems. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 2011, 164, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, M.C.; Chiou, S.Y.; Weng, C.Y.; Wang, L.; Ho, C.T.; Wu, M.J. Curcuminoids distinctly exhibit antioxidant activities and regulate expression of scavenger receptors and heme oxygenase-1. Molecular nutrition & food research 2013, 57, 1598–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Min, K.-j.; Um, H.J.; Cho, K.-H.; Kwon, T.K. Curcumin inhibits oxLDL-induced CD36 expression and foam cell formation through the inhibition of p38 MAPK phosphorylation. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2013, 58, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, A.; Tuberoso, C.I.G.; Atzeri, A.; Melis, M.P.; Bifulco, E.; Dessì, M.A. Antioxidant profile of strawberry tree honey and its marker homogentisic acid in several models of oxidative stress. Food Chemistry 2011, 129, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atallah, M.M.; Khalid, F.D.; Sulaiman, Y.A. In Vitro Study of the Effect of Vanillin Derivatives on Aryl Esterase, Troponine and Lipid Profile in Atherosclerosis Patients as Compared to Normal Subjects. Tikrit Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 17, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammino, L. Complexes of arzanol with a Cu2+ ion: a DFT study. Journal of Molecular Modeling 2017, 23, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gao, X.; Ou, J.; Chen, G.; Ye, L. Antimicrobial activity and mechanism of anti-MRSA of phloroglucinol derivatives. DARU Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2024, 32, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.; Tabassum, N.; Bamunuarachchi, N.I.; Kim, Y.-M. Phloroglucinol and Its Derivatives: Antimicrobial Properties toward Microbial Pathogens. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2022, 70, 4817–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, B.; Xu, J.; Xu, F.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Zhou, C. Phloroglucinol promotes fucoxanthin synthesis by activating the cis-zeatin and brassinolide pathways in Thalassiosira pseudonana. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2022, 88, e02160–e02121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, C.; Dupret, J.-M.; Rodrigues Lima, F. The structure of brain glycogen phosphorylase—from allosteric regulation mechanisms to clinical perspectives. The FEBS Journal 2017, 284, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, P.J. Glycogen and its metabolism. Current molecular medicine 2002, 2, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfsdorf, J.I.; Weinstein, D.A. Glycogen storage diseases. Metabolic Aspects of Chronic Liver Disease 2003, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloix, J.-F.; Hévor, T. Glycogen as a putative target for diagnosis and therapy in brain pathologies. International Scholarly Research Notices 2011, 2011, 930729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, M.E.; Anderson, D.G.; Hertz, L. Inhibition of glycogenolysis in astrocytes interrupts memory consolidation in young chickens. Glia 2006, 54, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, J.; Gruart, A.; García-Rocha, M.; Delgado-García, J.M.; Guinovart, J.J. Glycogen accumulation underlies neurodegeneration and autophagy impairment in Lafora disease. Human molecular genetics 2014, 23, 3147–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, N.; Morishita, R. The roles of lipid and glucose metabolism in modulation of β-amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2015, 7, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, J.C.; Treleaven, C.M.; Fidler, J.A.; Tamsett, T.J.; Bao, C.; Searles, M.; Taksir, T.V.; Misra, K.; Sidman, R.L.; Cheng, S.H. Metabolic signatures of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis reveal insights into disease pathogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 10812–10817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertz, H.-J.; Cervos-Navarro, J.; Frydl, V.; Schultz, F. Glycogen accumulation of the aging human brain. Mechanisms of ageing and development 1985, 31, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.M.; Kantsadi, A.L.; Leonidas, D.D. Natural products and their derivatives as inhibitors of glycogen phosphorylase: potential treatment for type 2 diabetes. Phytochemistry Reviews 2014, 13, 471–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantsadi, A.L.; Apostolou, A.; Theofanous, S.; Stravodimos, G.A.; Kyriakis, E.; Gorgogietas, V.A.; Chatzileontiadou, D.S.; Pegiou, K.; Skamnaki, V.T.; Stagos, D. Biochemical and biological assessment of the inhibitory potency of extracts from vinification byproducts of Vitis vinifera extracts against glycogen phosphorylase. Food and chemical toxicology 2014, 67, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobs, S.; Fridrich, D.; Hofem, S.; Pahlke, G.; Eisenbrand, G. Natural flavonoids are potent inhibitors of glycogen phosphorylase. Mol Nutr Food Res 2006, 50, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.; Elhassan, G.; Khalid, A.; Shafiq, M.; Tariq, S.S.; Alsuwat, M.A.; Elfatih, F.; Yagi, S.; Abdallah, H.H.; Mahomoodally, M.F.; Ul-Haq, Z. In-vitro and in-silico exploration of glycogen phosphorylase inhibition by Aloe sinkatana anthraquinones. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, N.; James, R.; Saha, D.; Das, B.K. Phytochemicals as Autophagy Modulators in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Current Bioactive Compounds 2025, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, S.; Moradi, S.Z.; Moradi, S.Y.; Piri, S.; Shiri Varnamkhasti, B.; Piri, S.; Khirehgesh, M.R.; Bishayee, A.; Casarcia, N.; Bishayee, A. Phytochemicals regulate cancer metabolism through modulation of the AMPK/PGC-1α signaling pathway. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, P.; Renu, K.; Ali, E.M.; Genena, M.A.M.; Veeraraghavan, V.; Sekar, R.; Sekar, A.K.; Tejavat, S.; Barik, P.; Abdallah, B.M. Promising and challenging phytochemicals targeting LC3 mediated autophagy signaling in cancer therapy. Immunity, Inflammation and Disease 2024, 12, e70041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattathi, V.W.; Kumari, S.; Dahiya, P.; Bhatia, R.K.; Bhatt, A.K.; Minhas, B.; Kaushik, N. Exploring the Potential of Dietary Phytochemicals in Cancer Therapeutics: Modulating Apoptosis and Autophagy. In Role of Autophagy and Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer Treatment: Principles and Current Strategies; Mishra, N., Kaundal, R.K., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 309–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, A.; Liu, M.; Zheng, Y.; Yan, W.; Pan, L.; Li, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhang, X.; Cao, M.; Wu, Z.; et al. Natural compounds modulate the autophagy with potential implication of stroke. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2021, 11, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, S.; Gao, K.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, C.; Shen, Z.; Guo, Y.; Li, Z.; Wan, Z.; Liu, C.; Mei, X. Resveratrol protects against spinal cord injury by activating autophagy and inhibiting apoptosis mediated by the SIRT1/AMPK signaling pathway. Neuroscience 2017, 348, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Chen, N. Resveratrol as a Natural Autophagy Regulator for Prevention and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2017, 9, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, H.; Yang, S.; Yang, S.; Zeng, J.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ma, X.; Dong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; et al. The mechanism of curcumin to protect mouse ovaries from oxidative damage by regulating AMPK/mTOR mediated autophagy. Phytomedicine 2024, 128, 155468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Yu, B.; Kou, J. Schizandrin Protects against OGD/R-Induced Neuronal Injury by Suppressing Autophagy: Involvement of the AMPK/mTOR Pathway. Molecules 2019, 24, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, A.M.; Meléndez, C.M.; Uribe, D.; Pedroza-Díaz, J. Synergistic effects of natural compounds and conventional chemotherapeutic agents: recent insights for the development of cancer treatment strategies. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biason-Lauber, A.; Böni-Schnetzler, M.; Hubbard, B.P.; Bouzakri, K.; Brunner, A.; Cavelti-Weder, C.; Keller, C.; Meyer-Böni, M.; Meier, D.T.; Brorsson, C. Identification of a SIRT1 mutation in a family with type 1 diabetes. Cell metabolism 2013, 17, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.; Mendes, A.F. Monoterpenes as sirtuin-1 activators: therapeutic potential in aging and related diseases. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, S.; Roohbakhsh, A.; Pourbarkhordar, V.; Karimi, G. The Cardiovascular Protective Function of Natural Compounds Through AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α Signaling Pathway. Food Science & Nutrition 2024, 12, 9998–10009. [Google Scholar]

- Iside, C.; Scafuro, M.; Nebbioso, A.; Altucci, L. SIRT1 activation by natural phytochemicals: an overview. Frontiers in pharmacology 2020, 11, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.H.; Islam, A.; Liu, Y.H.; Weng, C.W.; Zhan, J.H.; Liang, R.H.; Tikhomirov, A.S.; Shchekotikhin, A.E.; Chueh, P.J. Antibiotic heliomycin and its water-soluble 4-aminomethylated derivative provoke cell death in T24 bladder cancer cells by targeting sirtuin 1 (SIRT1). Am J Cancer Res 2022, 12, 1042–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Ciriani, M.; Falé, P.L.V.; Teixeira, V.; Madeira, P.; Machuqueiro, M.; Pacheco, R.; Florêncio, M.H.; Ascensão, L.; Serralheiro, M.L.M. Antiacetylcholinesterase activity and docking studies with chlorogenic acid, cynarin and arzanol from Helichrysum stoechas (Lamiaceae). Medicinal Chemistry Research 2017, 26, 2942–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iside, C.; Scafuro, M.; Nebbioso, A.; Altucci, L. SIRT1 Activation by Natural Phytochemicals: An Overview. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2020, 11 - 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Guo, B.; Tao, K.; Li, F.; Liu, Z.; Yao, H.; Feng, D.; Liu, X. Inhibition of SIRT1 in hippocampal CA1 ameliorates PTSD-like behaviors in mice by protections of neuronal plasticity and serotonin homeostasis via NHLH2/MAO-A pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 518, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, R.; Penninx, B.W.; Madar, V.; Xia, K.; Milaneschi, Y.; Hottenga, J.J.; Hammerschlag, A.R.; Beekman, A.; van der Wee, N.; Smit, J.H.; et al. Gene expression in major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2016, 21, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libert, S.; Pointer, K.; Bell, E.L.; Das, A.; Cohen, D.E.; Asara, J.M.; Kapur, K.; Bergmann, S.; Preisig, M.; Otowa, T.; et al. SIRT1 activates MAO-A in the brain to mediate anxiety and exploratory drive. Cell 2011, 147, 1459–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.; Njiki, S.; Mbemi, A.; Yedjou, C.G.; Tchounwou, P.B. Pharmacological Effects of Cisplatin Combination with Natural Products in Cancer Chemotherapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakibaei, M.; Kraehe, P.; Popper, B.; Shayan, P.; Goel, A.; Buhrmann, C. Curcumin potentiates antitumor activity of 5-fluorouracil in a 3D alginate tumor microenvironment of colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhrmann, C.; Yazdi, M.; Popper, B.; Shayan, P.; Goel, A.; Aggarwal, B.B.; Shakibaei, M. Resveratrol Chemosensitizes TNF-β-Induced Survival of 5-FU-Treated Colorectal Cancer Cells. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, P.; Wang, P.; Yang, C.S.; Wang, X.; Feng, Q. EGCG enhances cisplatin sensitivity by regulating expression of the copper and cisplatin influx transporter CTR1 in ovary cancer. PloS one 2015, 10, e0125402. [Google Scholar]

- Rifaï, K.; Idrissou, M.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Bignon, Y.-J.; Bernard-Gallon, D. Breaking down the Contradictory Roles of Histone Deacetylase SIRT1 in Human Breast Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, P. The protective effects of activating Sirt1/NF-κB pathway for neurological disorders. Reviews in the Neurosciences 2022, 33, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilmac, S.; Kuscu, N.; Caner, A.; Yildirim, S.; Yoldas, B.; Farooqi, A.A.; Tanriover, G. SIRT1/FOXO Signaling Pathway in Breast Cancer Progression and Metastasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).