Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Methods

- Protein Targets

- Catalytic domain: 3BTA, 3C88

- Receptor-binding domain: 3AZV

- Light chain in complex with 4-chlorocinnamic hydroxamate: 2ILP

- Proteins were prepared by removing water molecules, adding hydrogens, and assigning Gasteiger charges.

- Docking Protocol

2.1. Protein Preparation

2.2. Ligand Preparation

2.2.1. Center Grid Box Settings for AutoDock Vina Using PyRx

- PDB: 3BTA – Blind docking

- Center Coordinates: X = 39.8533, Y = 43.6838, Z = 56.9189

- Grid Box Size: X = 135.34, Y = 96.37, Z = 82.09

- Exhaustiveness: 8

- PDB: 3AZV – Blind docking

- Center Coordinates: X = -1.6175, Y = 12.663, Z = -6.2017

- Grid Box Size: X = 48.73, Y = 86.24, Z = 66.17

- Exhaustiveness: 8

- PDB: 2ILP – Selective docking (ligand binding site)

- Center Coordinates: X = -3.261, Y = -9.413, Z = 22.006

- Grid Box Size: X = 12.64, Y = 12.64, Z = 12.64

- Exhaustiveness: 8

- PDB: 3C88 – Selective docking (ligand binding site)

- Center Coordinates: X = 27.330, Y = 21.208, Z = 56.022

- Grid Box Size: X = 17.28, Y = 17.28, Z = 17.28

- Exhaustiveness: 8

3. Results and Discussion

- Top Binders (≤ –9.0 kcal/mol):

- Hypericin (–10.0 kcal/mol)

- Hesperidin (–9.9 kcal/mol)

- Baicalin (–9.9 kcal/mol)

- Silibinin (–9.9 kcal/mol)

- Epicatechin Gallate (–9.8 kcal/mol)

- Silymarin (–9.8 kcal/mol)

- Scutellarin (–9.6 kcal/mol)

- Naringin (–9.3 kcal/mol)

- Daidzin (–9.3 kcal/mol)

- Astringin (–9.2 kcal/mol)

- Genistin (–9.2 kcal/mol)

- Rhaponticin (–9.2 kcal/mol)

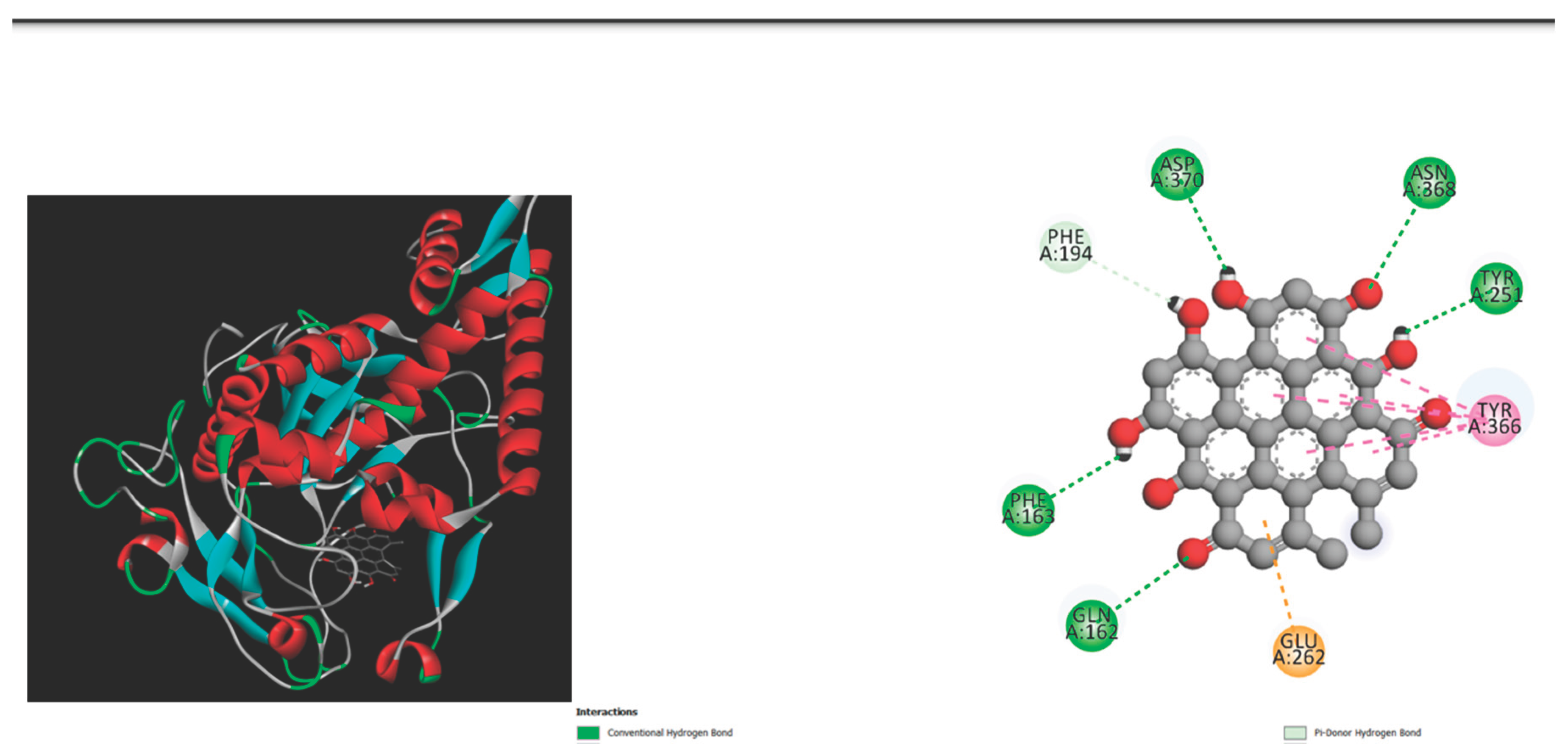

- Hypericin retains strong binding in both blind and selective docking (–10.6 → –10.0 kcal/mol), confirming its potential as a potent multitarget inhibitor.

- Hesperidin consistently shows high affinity (–10.8 → –9.9 kcal/mol), indicating effective interaction across multiple BoNT domains.

- Silibinin also demonstrates strong binding (–10.1 → –9.9 kcal/mol), supporting its potential as a catalytic site inhibitor.

3.1. Final Top Results

3.1.1. Binding Energies

| Compound | 3BTA (kcal/mol) | 3AZV (kcal/mol) | 2ILP (kcal/mol) | 3C88 (kcal/mol) |

| Hesperidin | -10.8 | -9.5 | -8.7 | -9.9 |

| Hypericin | -10.6 | -8.6 | -10.0 | -10.0 |

| Silibinin | -10.1 | -9.0 | -6.3 | -9.9 |

3.1.2. Observations

- Flavonoids and polyphenols dominate the top binders due to multiple hydrogen bond donors/acceptors and aromatic systems capable of π-π stacking.

- Hypericin is the strongest multitarget ligand, suggesting both catalytic inhibition and interference with receptor binding.

- Compounds like Xanthone and Epicatechin Gallate showed selective high affinity for the light chain, mimicking inhibitor-like behavior.

3.1.3. Comparative Analysis Across Domains

- Catalytic domain (3BTA, 3C88) generally exhibited stronger binding (up to –10.8 kcal/mol) than receptor-binding domain (3AZV, up to –9.5 kcal/mol).

- Multitarget compounds may offer dual inhibition mechanisms, potentially enhancing neutralization efficacy.

3.1.4. Discussion

4. Conclusion

- Key Points

- Molecular docking highlights Hypericin, Hesperidin, and Silibinin as potent multitarget BoNT inhibitors.

- Flavonoids and polyphenols represent the most promising chemical classes for BoNT inhibition.

- The study provides a basis for further in vitro, in vivo, and pharmacokinetic studies to develop safe natural therapeutics against BoNT/A.

References

- Jakhar, R., Dangi, M., Khichi, A., & Chhillar, A. K. (2020). Relevance of molecular docking studies in drug designing. Current Bioinformatics, 15(4), 270-278. [CrossRef]

- Scotti, L., JB Mendonca Junior, F., M Ishiki, H., F Ribeiro, F., K Singla, R., M Barbosa Filho, J., ... & T Scotti, M. (2017). Docking studies for multi-target drugs. Current drug targets, 18(5), 592-604.

- Abdelsattar, A. S., Dawoud, A., & Helal, M. A. (2021). Interaction of nanoparticles with biological macromolecules: A review of molecular docking studies. Nanotoxicology, 15(1), 66-95. [CrossRef]

- Tighe, A. P., & Schiavo, G. (2013). Botulinum neurotoxins: mechanism of action. Toxicon, 67, 87-93. [CrossRef]

- Davletov, B., Bajohrs, M., & Binz, T. (2005). Beyond BOTOX: advantages and limitations of individual botulinum neurotoxins. Trends in neurosciences, 28(8), 446-452. [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, H. (1980). Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin. Microbiological reviews, 44(3), 419-448.

- Aoki, K. R., & Guyer, B. (2001). Botulinum toxin type A and other botulinum toxin serotypes: a comparative review of biochemical and pharmacological actions. European Journal of Neurology, 8, 21-29. [CrossRef]

- Peng Chen, Z., Morris Jr, J. G., Rodriguez, R. L., Shukla, A. W., Tapia-Núñez, J., & Okun, M. S. (2012). Emerging opportunities for serotypes of botulinum neurotoxins. Toxins, 4(11), 1196-1222. [CrossRef]

- Aoki, K. R. (2001). Pharmacology and immunology of botulinum toxin serotypes. Journal of Neurology, 248(Suppl 1), I3-I10. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Masuyer, G., Zhang, J., Shen, Y., Lundin, D., Henriksson, L., ... & Stenmark, P. (2017). Identification and characterization of a novel botulinum neurotoxin. Nature communications, 8(1), 14130. [CrossRef]

- Trott, O., & Olson, A. J. (2010). AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of computational chemistry, 31(2), 455-461. [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J., Santos-Martins, D., Tillack, A. F., & Forli, S. (2021). AutoDock Vina 1.2. 0: new docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. Journal of chemical information and modeling, 61(8), 3891-3898.

- Seeliger, D., & de Groot, B. L. (2010). Ligand docking and binding site analysis with PyMOL and Autodock/Vina. Journal of computer-aided molecular design, 24(5), 417-422.

- Pettersen, E. F., Goddard, T. D., Huang, C. C., Couch, G. S., Greenblatt, D. M., Meng, E. C., & Ferrin, T. E. (2004). UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of computational chemistry, 25(13), 1605-1612. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, R., Devi, A., & Mishra, S. (2015). Molecular docking and molecular dynamics studies reveal structural basis of inhibition and selectivity of inhibitors EGCG and OSU-03012 toward glucose regulated protein-78 (GRP78) overexpressed in glioblastoma. Journal of molecular modeling, 21(10), 272. [CrossRef]

- Dallakyan, S., & Olson, A. J. (2014). Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. In Chemical biology: methods and protocols (pp. 243-250). New York, NY: Springer New York.

| Ligand | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

| Folic_Acid | -10.2 |

| Hesperidin | -10.8 |

| Hypericin | -10.6 |

| Icariin | -10.3 |

| Silibinin | -10.1 |

| Ligand | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

| Hesperidin | -9.5 |

| Rutin | -9.1 |

| Silibinin | -9.0 |

| Ligand | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

| Hypericin | –10.0 |

| Quercitrin | –9.0 |

| Xanthone | –8.9 |

| Epicatechin Gallate | –8.8 |

| Hesperidin | –8.7 |

| Myricitrin | –8.6 |

| Rhaponticin | –8.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).