1. Introduction

The growing interest among researchers is directed toward understanding how generative artificial intelligence (AI) impacts new roles of teachers, students and the professional autonomy of educators within educational processes [

1,

2,

3]. Contemporary education increasingly highlights the differences between traditional teaching approaches and those integrating AI as instructional support. Traditional education positions the teacher predominantly as a transmitter of knowledge, whereas modern AI-integrated education transforms the teacher’s role into that of facilitator and mentor. In the context of contemporary pedagogy, artificial intelligence facilitates personalised learning adapted to individual student needs, pace and style, in contrast to the uniform approach characteristic of traditional models [

4]. Classic teaching methods rely on periodic, often standardised forms of assessment, whereas AI systems enable continuous progress monitoring and real-time formative feedback, enhancing students’ confidence and skill development [

5]. Students in traditional education typically assume passive roles, whereas interactive AI platforms in contemporary classrooms encourage active participation, collaboration and inquiry. Artificial intelligence further supports the effective development of higher-order cognitive skills such as critical thinking, problem solving and digital literacy, overcoming the predominantly reproductive character of classical instruction. AI tools allow rapid and detailed analysis of student behaviours and progress, identifying areas requiring additional attention and support—tasks that traditionally demand significant teacher time and effort. The use of digital resources and intelligent tutoring systems expands educational accessibility, particularly benefiting students with special educational needs or those in remote areas. Within such educational environments, the teacher remains a critical element of the educational process but is empowered by technology that facilitates lesson planning, differentiated instruction, classroom implementation and evaluation of achievements. This technological empowerment frees teachers’ time and motivates further professional development. Thus, integrating AI tools does not replace human involvement but rather enhances the quality of educational processes in alignment with twenty-first-century educational demands. Developing metacognitive abilities among future teachers is becoming a key competency, enabling educators to reflect, plan and adapt instruction to students’ needs [

6]. Successful integration of AI tools into educational processes and teacher training requires educators to be trained in AI utilisation, thus improving instructional quality and fostering critical understanding of technology’s role in education [

7,

8]. A recent analysis of 24 smart-education policies from various countries and organisations identified key strategies and trends in smart-education development. Although smart education is recognised as a global priority, its implementation depends significantly on each country’s economic development and infrastructure, with investments in human capital and digital environments being crucial for success [

9].

2. AI Avatars and the Serbian Educational Context

Within the Serbian educational context, the implementation of smart-education initiatives reflects a dedicated commitment to enhancing the quality and inclusivity of education through digital transformation. Serbia’s educational reforms increasingly advocate the integration of digital competencies and advanced AI technologies into curricula and teacher-training programmes. Consequently, evaluating teacher perceptions shaped by non-formal educational experiences becomes essential, as educators’ acceptance and effective integration of these innovative tools significantly influence their successful implementation. This research specifically addresses the existing gap in understanding how such non-formal experiences shape Serbian educators’ perceptions and attitudes toward interactive educational avatars, thereby providing valuable insights for policymakers, educators and researchers involved in Serbia’s ongoing educational modernisation. In the Serbian context, literature highlights the increasing alignment of national education policies with global smart-education initiatives [

4,

10,

11]. These policies emphasise integrating digital competencies and advanced AI technologies into teacher-training programmes and curricula, reflecting broader international trends toward educational innovation and modernisation.

Interactive educational avatars currently represent one of the most revolutionary and promising applications of artificial intelligence in education. They hold great potential not only for improving teacher training but also for enhancing the learning process for students themselves. Their significance extends beyond technological innovation alone; avatars serve as pedagogical tools capable of contributing to personalisation, inclusivity, emotional support and the development of diverse skills. Individualised instruction constitutes one of the primary advantages offered by AI avatars. Through detailed analysis of student data, avatars can provide highly personalised learning experiences tailored specifically to each learner’s unique strengths, weaknesses and learning styles. This personalised approach significantly increases student engagement, motivation and learning efficiency, ultimately resulting in improved academic outcomes. Additionally, AI avatars notably enhance adaptive learning environments by continuously adjusting the complexity and nature of instructional content based on real-time assessments of learner performance. This adaptive capability allows educators to better address individual student needs, ensuring optimal progress and appropriate challenge levels for each learner. Adaptive support particularly benefits learners with special educational needs, enabling differentiated instructional strategies that traditional methods cannot effectively accommodate.

Studies focused on Serbia underscore significant institutional contributions, notably from entities such as the University of Belgrade—Faculty of Education and the Centre for Robotics and Artificial Intelligence in Education (CRAIE)

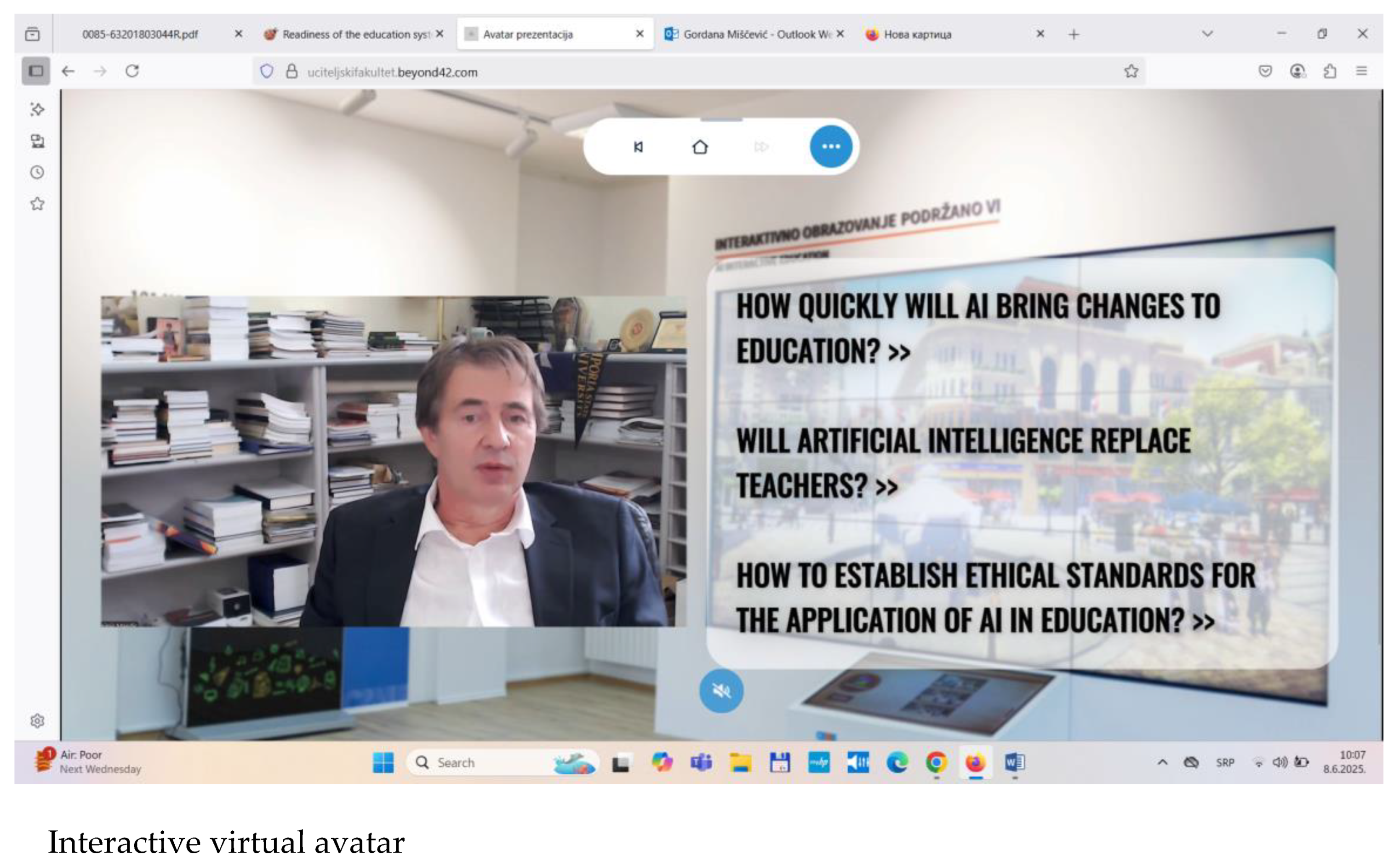

1. CRAIE actively promotes comprehensive avatar integration through structured professional-development programmes and robust ethical frameworks. The following examples illustrate avatars utilised by CRAIE. The first two examples represent classical avatars, while the third features an interactive virtual avatar.

In the first example, a classical avatar depicts a teacher who authored a textbook, designed to introduce university students to a traditional textbook presented in print form. This avatar acquaints students, in a modern manner, with key chapters of the textbook and explains optimal methods for acquiring knowledge and competencies in STEM methodology. The avatar delivers information in English, while all information is subtitled in Serbian, with the capability for translation into any other language required by the country in which it is used.

Figure 1.

Classical avatar for textbook presentation.

Figure 1.

Classical avatar for textbook presentation.

The second example depicts another classical avatar presenting fundamental teacher competencies defined by UNESCO standards. Auditory information is provided in English, while subtitles are presented in Chinese. After introducing general competencies, digital competencies tailored specifically to teacher needs in an era of intensive online learning and AI application in both formal and non-formal education are elaborated. These avatars are utilised by CRAIE for continuous professional development of teachers, employing hybrid models that combine asynchronous and synchronous online-learning technologies along with AI software integrated with traditional face-to-face instruction. Teachers are encouraged to develop critical thinking through comparative analyses of content generated by AI software and traditional textbooks reviewed by subject experts. This approach fosters the creation of personalised instructional materials, individually crafted by each teacher based on diverse sources and personal conclusions derived from comparative analyses.

Figure 2.

Classical avatar for identifying digital competencies of teachers.

Figure 2.

Classical avatar for identifying digital competencies of teachers.

The third example presents an interactive virtual avatar based on artificial intelligence. It was trained initially on materials published in the papers and books by Professor Danimir Mandić and subsequently expanded with content from other authors in computer science, AI and educational technology. In addition to these areas, in collaboration with the medical association HISPA, the avatar is trained to engage in dialogue and respond to questions related to heart disease and cardiovascular conditions. Integrating interactive avatars into educational and communication systems represents a highly sophisticated engineering challenge, requiring coordinated inclusion of multiple AI domains, signal processing and real-time software-system design. The avatar’s key functionalities are enabled by advanced machine-learning and deep-learning algorithms, resulting in a multi-layered architecture capable of multimodal processing and real-time user interaction. At the core of the system are natural-language-processing models that provide semantic and syntactic analysis of input text and speech. Pre-trained large language models such as GPT-4o, LLaMA or BERT variants facilitate the generation of natural, contextually relevant and coherent avatar speech. Alongside language processing, the system includes modules for speech processing—automatic speech recognition and text-to-speech—based on deep neural networks like Conformer, Wav2Vec 2.0 and Tacotron 2, ensuring natural real-time voice interaction. From a visual perspective, additional enhancements are possible by implementing computer-vision modules that enable the detection and tracking of users’ non-verbal signals, including face detection, micro-expression analysis and body-movement tracking. These tasks employ convolutional and recurrent neural networks as well as transformers for processing visual data sequences. Emotion recognition is further realised using multimodal-fusion models that integrate auditory and visual data to detect emotions, stress, confusion and other cognitive-affective user states.

Figure 3.

Interactive virtual avatar.

Figure 3.

Interactive virtual avatar.

The central component of the adaptive behaviour of the avatar consists of a personalisation layer based on machine learning, which continuously updates the user model through sequential-learning algorithms (online learning). These models use user feedback, historical interaction data and evaluation outcomes to optimise content adaptability, communication tone and information-complexity levels. From an implementation perspective, the system requires a distributed and scalable infrastructure capable of being deployed in the cloud (e.g., Microsoft Azure AI, AWS AI Services), supported by real-time stream processing, GPU acceleration and orchestration of complex AI services. The realisation of the visual representation of avatars demands high-quality character-rendering engines such as the NVIDIA Omniverse Avatar platform, which enables synchronisation of voice and facial expressions, realistic animations and emotional expressiveness. A particular engineering challenge involves synchronising multiple heterogeneous AI modules, managing real-time latencies and maintaining natural interactions despite uncertainties in input signals (e.g., speech noise, incomplete visual data). Additionally, data security, user privacy and ethical standards constitute key factors in the design of such systems, especially in educational and healthcare applications. The development of interactive avatars based on this architectural model opens up a broad spectrum of potential applications, not only in education but also in telemedicine, remote psychological support, professional training through complex interpersonal situation simulations and intelligent customer-support systems.

3. Method

The aim of the research was to examine whether experiences gained through non-formal education using avatars influence educators’ attitudes toward the use of avatars for educational purposes. The primary hypothesis was that there is a positive correlation between experiences with avatars (classical avatars and interactive avatars) and educators’ attitudes toward using avatars.

Data were analysed using correlation and interaction-regression models. The quantitative analysis was conducted using R statistical software. The research involved a sample of 173 respondents employed at educational levels ranging from preschool to university in the Republic of Serbia (see

Table 1). We utilised an online questionnaire designed to collect data on participants’ current levels of awareness regarding this topic. The instrument was a questionnaire distributed online, containing questions through which it was possible to examine information about the respondents’ institution, the usage of classical and interactive avatars and an attitude scale consisting of ten items assessing respondents’ attitudes toward using avatars for educational purposes. The questions addressed cognitive, affective and behavioural dimensions of attitude, and the instrument itself fulfilled all metric characteristics necessary to be considered a reliable tool upon which all subsequent conclusions could be drawn.

4. Results and Discussion

Table 1 summarises attitudes toward using avatars across teaching levels. University professors reported the highest mean attitude scores, whereas teachers of younger grades reported the lowest. Correlation analyses showed significant positive relationships between experience with classical avatars and attitudes (r = 0.51,

p < 0.001) and between experience with interactive avatars and attitudes (r = 0.39,

p < 0.001). The regression model was significant (

F(2, 169) = 34.49,

p < 0.001) and accounted for 29 % of the variance in attitudes (

R² = 0.29); both predictor variables contributed uniquely (β₍classical₎ = 2.82, β₍interactive₎ = 1.90).

Correlation between the experience of using classical avatars and attitudes toward using avatars for educational purposes: r = 0.51, p < 0.001.

Correlation between the experience of using interactive avatars and attitudes toward using avatars for educational purposes: r = 0.39, p < 0.001.

Based on the data obtained, the hypothesis is confirmed, as experience with avatars significantly positively correlates with attitudes toward using avatars for educational purposes.

A regression model was also utilised:

Attitude toward using avatars for educational purposes = 10.22 + 2.82 × (experience using classical avatars) + 1.90 × (experience using interactive avatars).

The model was significant: F(2, 169) = 34.49, p < 0.001.

Explained variance: R² = 0.29.

Based on this analysis, experiences with classical avatars and experiences with interactive avatars are significant predictors of attitudes toward using avatars for educational purposes. The results indicate that educators’ experiences with classical and interactive avatars are significant predictors of their attitudes toward their use in educational settings. A higher level of prior use of classical avatars positively correlates with openness to implementing avatars in the teaching process. Particularly pronounced is the influence of interactive avatars, which enable two-way communication, content adaptation and greater user engagement. These findings suggest that informal experimentation with avatars may play a crucial role in reducing resistance to technological innovation in education. Aligned with this finding are the results of recent research indicating that university teachers displayed the most positive attitudes due to having the most extensive experiences and opportunities to use avatars [

12]. The Faculty of Education with CRAIE can play a critical role in operationalising and further applying the findings of this research. As an institution focused on developing and promoting new technologies in education, the Faculty and CRAIE can also act as a bridge connecting students, researchers and educators by providing technical support and expertise in implementing avatars. Through delivering contemporary education for students, as well as relevant training for educators across all educational levels, knowledge gained through non-formal education—identified as a significant predictor of positive attitudes in this research—could be further enhanced and improved.

The Faculty of Education with CRAIE can develop and distribute domestically created avatar platforms adapted specifically to the Serbian educational context, further facilitating the integration of these tools into everyday teaching. Future steps might include providing mentorship support and collaboration through various projects, enabling teachers to safely experiment with different types of avatars. Finally, as a research and development centre, CRAIE can contribute to further studying the effects of avatar usage in education and evaluating their effectiveness under real classroom conditions, thus closing the loop between research, practice and development.

5. Conclusion

Educational avatars significantly advance Serbia’s smart-education initiatives, demonstrating transformative potential in delivering personalised, adaptive and engaging instructional methodologies. Their implementation supports differentiated instruction, enabling educators to address individual learners’ needs more effectively, thus enhancing academic achievement and learner motivation. The successful integration of these innovative technologies into educational practices depends heavily on a structured, systematic approach to educator training, which must include ongoing professional development and continuous pedagogical support to ensure that educators are both proficient in technology use and knowledgeable about integrating these tools effectively into their teaching strategies. Robust ethical guidelines must underpin the widespread adoption of AI-driven avatars, addressing critical issues such as data privacy, transparency, algorithmic fairness and equitable access to technology-enhanced learning opportunities. Educators and policymakers must collaboratively establish clear, comprehensive ethical standards that safeguard the rights of students and teachers, build trust and ensure responsible and ethical technology use within educational environments.

Furthermore, sustained research efforts remain crucial for deepening the understanding of the long-term impacts and efficacy of avatar-based education. Longitudinal studies and systematic evaluations will be essential in identifying best practices, assessing scalability and understanding avatars’ influence on various educational outcomes, including cognitive development, social-emotional learning and digital literacy skills. Future research should particularly focus on exploring inclusivity, examining how avatars can support learners with special educational needs and those from diverse socio-economic backgrounds, thus promoting broader educational equity. Creating a supportive and innovative educational culture requires robust institutional backing, encompassing sufficient resources, advanced technological infrastructure and a commitment from educational leaders to encourage experimentation and innovation among educators. Institutions such as the Faculty of Education with the Centre for Robotics and Artificial Intelligence in Education (CRAIE) play a pivotal role by providing technical expertise, resources and continuous mentorship, thereby facilitating educators’ exploration and integration of avatars within diverse pedagogical contexts. Interdisciplinary collaboration remains integral to furthering the successful integration of AI-driven avatars into educational practices. Partnerships between educational researchers, technology developers, policymakers and practitioners are vital for aligning technological innovations with pedagogical objectives and ensuring that technology supports rather than dictates educational practices. Such collaborations can accelerate innovation, promote evidence-based practices and ensure that technological advancements are pedagogically meaningful and contextually relevant.

The strategic implementation and thoughtful integration of interactive educational avatars have the potential to significantly transform and enhance educational experiences within Serbia and beyond. Emphasising comprehensive educator training, robust ethical governance, rigorous research initiatives and collaborative interdisciplinary approaches will ensure that AI-driven avatars contribute meaningfully to creating inclusive, equitable and globally competitive educational environments. These combined efforts will solidify interactive avatars’ role in shaping the future of education in Serbia, paving the way for ongoing innovation and sustained improvement in educational quality and effectiveness.

6. Note

This research was conducted by the University of Belgrade—Faculty of Education as part of the project “Building the Critical Computer Skills for the Future-Ready Workforce” (No. 00136459) implemented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in partnership with the Ministry of Education, with the support of the Government of the Republic of Serbia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, D.M. and M.D.; methodology, D.M. and M.D.; formal analysis, M.D.; investigation, D.M.; resources, G.M.; data curation, M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.; writing—review and editing, G.M. and M.D.; visualisation, D.M.; supervision, G.M.; project administration, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of the project “Building the Critical Computer Skills for the Future-Ready Workforce” (No. 00136459) implemented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in partnership with the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Serbia. The project was supported by the Government of the Republic of Serbia.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it involved anonymised, voluntary survey responses with no sensitive personal data collected.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and respondents could withdraw at any time.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the educators who participated in this study and the staff of the Centre for Robotics and Artificial Intelligence in Education for facilitating access to avatar technologies. We are grateful to colleagues at the Faculty of Education for their constructive feedback.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

-

Karataş, F.; Eriçok, B.; Tanrikulu, L. Reshaping curriculum adaptation in the age of artificial intelligence: mapping teachers’ AI-driven curriculum adaptation patterns. British Educational Research Journal 2024, 51, 154–180. [CrossRef]

-

Milutinović, V.; Đorđević, S.; Mandić, D. Cryptography in organising online collaborative math problem solving. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education 2025, 13, 191–206. [CrossRef]

-

Zhai, X. Transforming teachers’ roles and agencies in the era of generative AI: perceptions, acceptance, knowledge and practices. Journal of Science Education and Technology 2024, 1–11. [CrossRef]

-

Mandić, D. Report on smart education in the Republic of Serbia. In Smart Education in China and Central & Eastern European Countries; Zhuang, R.; Liu, D.; Sampson, D.; et al., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 271–292. [CrossRef]

-

Wang, S. Hybrid models of piano instruction: how combining traditional teaching methods with personalised AI feedback affects learners’ skill acquisition, self-efficacy and academic locus of control. Education and Information Technologies 2025, 1–23. [CrossRef]

-

Radulović, B.; Džinović, M.; Miščević, G. Using a longitudinal trajectory of pre-service elementary school teachers’ metacognition as a quality indicator of higher education. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education 2024, 12, 251–257. [CrossRef]

-

Mandić, D.; Miščević, G.; Bujisić, Lj. Evaluating the quality of responses generated by ChatGPT. Metodicka teorija i praksa 2024, 27, 5–19. [CrossRef]

-

Mandić, D.; Miščević, G.; Babić, J.; Matović, S. Educational robots in teachers’ education. Research in Pedagogy 2024, 14, 361–376. [CrossRef]

-

Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Lin, R.; Zhu, H. Strategic framework and global trends of national smart-education policies. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, 1–13. [CrossRef]

-

Huang, R.; Liu, D.; Kanwar, A.S.; Zhan, T.; Yang, J.; Zhuang, R.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Adarkwah, M.A. Global understanding of smart education in the context of digital transformation. Open Praxis 2024, 16, 663–676. [CrossRef]

-

Ristić, M.; Mandić, D. Readiness of the education system for mobile learning. Sociološki pregled 2018, 52, 1044–1071. [CrossRef]

-

Mandić, D.; Miščević, G.; Ristić, M. Teachers’ perspectives on the use of interactive educational avatars: insights from non-formal training contexts. Research in Pedagogy 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).