1. Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most prevalent interstitial lung disease, characterized by a progressive and chronic course that remains not fully understood [

1,

2]. It involves the remodeling of the interstitium in distal airways and alveolar spaces, predominantly affecting the posterior basilar regions of the lung, typically beginning in a subpleural distribution [

3].The pathogenesis of IPF is complex, marked by repetitive scarring of the alveolar tissue [

4], and progresses slowly but is ultimately fatal, with an average survival of 2 to 4 years after diagnosis [

5]. It significantly impairs respiratory capacity and is a global concern due to its clinical severity [

6]. IPF is more prevalent among males in their sixth decade of life, largely attributed to the aging population [

4,

7] . In Brazil, approximately 16,000 IPF cases [

6] are reported, with an expected rise partly attributable to the increased use of electronic cigarettes.

As the disease progresses, respiratory capacity is significantly impaired, with a persistent dry cough and dyspnea as the most common symptoms. Patients may also experience acute exacerbations that necessitate oxygen supplementation [

7]. Currently, antifibrotic therapy is recommended in cases of IPF; however, the drugs Nintedanib and Pirfenidone delay disease progression but do not reverse fibrosis. Due to significant side effects and limited efficacy [

8,

9], it is crucial to study the pathophysiology of the disease for evaluating alternative therapeutic approaches, potentially leading to more effective treatments.

In Brazil, lung transplantation is almost the only option available for these individuals. In 2024, a total of 93 lung transplants were performed in the country, with 35 taking place in the state of Rio Grande do Sul [

10]. However, data from the Brazilian Association of Organ Transplants in 2025 indicates that 348 people are still waiting for this lifesaving procedure [

11].

Given the limited treatment options and the high demand for transplants in Brazil, there is an urgent need to explore other therapeutic avenues that could reduce patients’ reliance on transplant waiting lists. One promising area of interest is the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), which is well known for its role in promoting fibrosis through Angiotensin II (AngII) [

12,

13]. Attempts to treat fibrosis have focused on using AT1 receptor blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors [

9], which target AngII’s fibrotic pathways. Unfortunately, these treatments did not yield significant improvements in halting fibrosis progression, leading to a decline in research focus on the RAS. However, the discovery of new peptides within this system has reignited interest, highlighting the importance of maintaining a balance between the fibrotic axis driven by AngII and the antifibrotic pathways involving Angiotensin- (1-7) (Ang-(1-7)) and Alamandine (ALA) [

14].

The understanding of the RAS has evolved significantly with the discovery of new peptides and enzymes, shifting from the classic view to a contemporary perspective. This includes Ang-(1-7), ALA, and ACE2, which play a crucial role in maintaining balance in the lungs, a key site for RAS activation [

15]. Recent studies in patients with IPF demonstrated that this system has been evaluated in patients with IPF, revealing a probable imbalance in the RAS axes [

16].

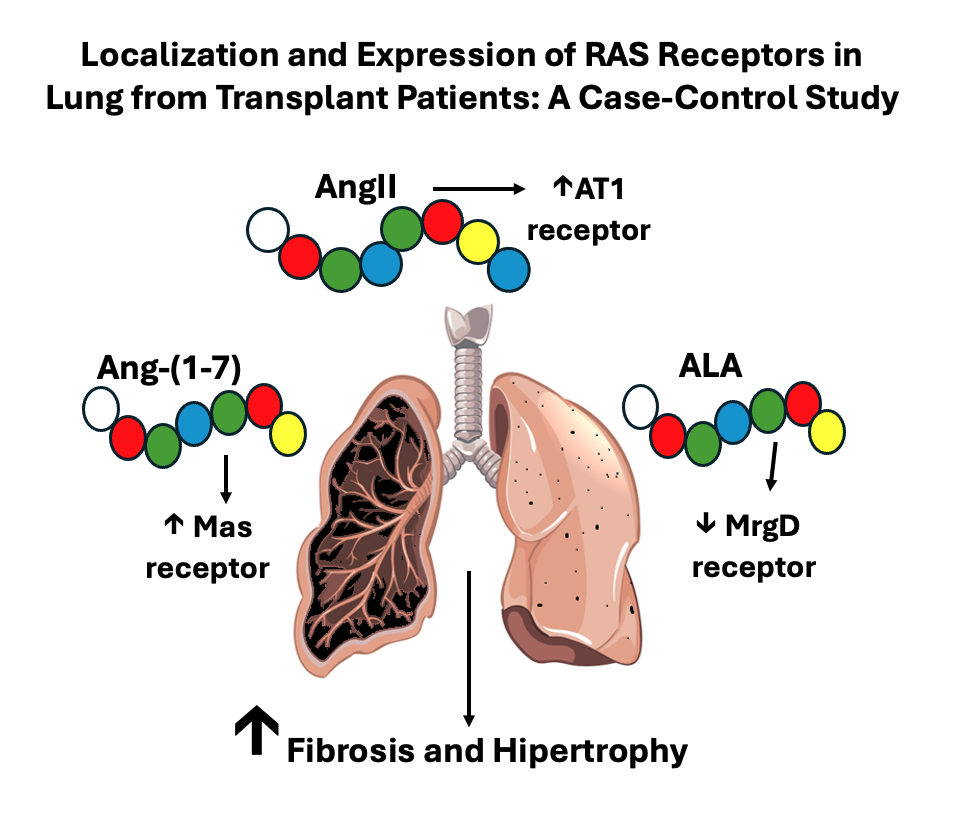

In the classic axis, the AT1 receptor primarily mediates the effects of AngII, which can lead to harmful outcomes such as inflammation and fibrosis when this pathway becomes dominant [

17]. Conversely, other peptides and their receptors, such as Ang-1-7, which binds to the Mas receptor, exhibit vasodilatory, anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects. Additionally, the discovery of the peptide ALA, which binds to the MrgD receptor, show similar actions to Ang- (1-7) [

18], providing protective effects on the lungs [

19].

Due to the severity of IPF and the possible RAS imbalance involved, a deeper understanding of its pathophysiology may support the development of alternative treatments, either alone or in combination, that improve IPF management. In this scenario, this study aims to investigate the location and expression of the AT1, Mas, and MrgD receptors in the lung tissue and of Angiotensin I (Ang I), Ang II, Angiotensin A (Ang A), Ang- (1-7) and ALA peptides in the plasma of patients with and without IPF.

2. Materials and Methods

This article is part of a larger study approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre and the Irmandade Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre (Number 69947517.2.0000.5345/69947517.2.3001.5335). All procedures followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki

This case-control study involved 19 intraoperative patients undergoing surgical procedures, including lobectomy and/or pulmonary segmentectomy (control group) and lung transplantation (IPF group), at a renowned transplant hospital in southern Brazil. From May 2021 to May 2023, 1cm3 of lung tissue and 4mL of blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes with protease inhibitor P8340 (Sigma-Aldrich®). Plasma was collected from the blood sample after refrigerated centrifugation. Lung tissue samples for the IPF group were collected from diseased lung tissue, while for the control group, they were collected from the most distal margin of the resected tissue, where there is the highest likelihood of representing normal, healthy characteristics. The collected plasma and tissues were frozen in nitrogen liquid and stored at -80ºC.

The inclusion criteria were adult IPF patients over the age of 18, of both sexes, who had undergone lung transplantation, and patients undergoing lung resection to treat bronchial carcinoma. Exclusion criteria involved patients with clinical disorders that would compromise their participation or performance in this study and patients taking ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers and angiotensin receptor blockers.

Demographic and clinical data such as age, race, gender, weight, height, body mass index, smoking status, oxygen use, spirometry, lung scintigraphy, systolic pulmonary artery pressure (SPAP), and the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) were collected from secondary data in the patients’ medical records. The data collected was stored in an electronic database and treated confidentially.

2.1. Western Blot Analysis of Pulmonary RAS Receptor Expression

Thawed lung tissue samples (-80ºC) were maceraded in liquid nitrogen, homogenized using RIPA Lysis Buffer (10x, Millipore), protease inhibitor P8340 (Sigma-Aldrich®), and ultrapure water, followed by centrifugation. To ensure consistent protein amounts, 75μg of protein were subjected to one-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using a batch system with a 10% gel.

In a cooled Bio-Rad transfer unit, the separated proteins were then transferred by electrophoresis to membranes using buffer containing 20 mM Tris, 150 mM glycine, 20% (v/v) methanol, and 0.02% (w/v) SDS (pH=8.2). Membranes were incubated for 1.5 hours in a blocking solution (5% (w/v) skimmed milk in 0.1% (w/v) Tris-Tween 20 buffer to prevent non-specific binding. The membranes were processed by immunodetection using primary antibodies: angiotensin II AT1 receptor polyclonal antibody (Enzo®), MGPRF polyclonal antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific®), and Mas polyclonal antibody (Novus Biologicals®).

The samples were then incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies conjugated to peroxidase (HRP; Sigma-Aldrich®), which react with a chemiluminescent substrate. Band intensity was determined by quantitative densitometry analysis using Image Lab Software (Bio-Rad®). The results were normalized by densitometry of the total protein in these samples.

2.2. Immunohistochemical Mapping of RAS Receptors in Lung Tissue

The specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution for 48 hours to ensure optimal preservation, after which they were dehydrated, clarified and embedded in paraffin. The 4-micrometer histological sections were placed on salinized slides, and the immunohistochemical assay was carried out. The slides were heated in an oven at 75°C for 30 minutes to aid in deparaffinized, followed by xylene treatment and gradual rehydrated in a graded series of ethanol followed by distilled water. Antigen retrieval for anti-Mas1 Polyclonal antibody (ref. NBP1-60091, Novus Biologicals) and anti-MRGPRF Polyclonal antibody (ref. PA5-110966, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was performed in a water bath for 40 minutes at 95°C in 20 mM Tris / EDTA buffer (pH 9.0).

Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol, protected from light, and applied three times for 10 minutes each. Protein blocking was achieved with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hour. The sections were incubated overnight at 2-8°C with the primary antibodies anti-Mas (dilution 1:200) and anti- MRGPRF (dilution 1:200). Subsequently, the HRP-conjugated polymer (Envision + Dual Link-HRP system ref: K4061, Dako, CA, USA) was applied and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate (Liquid DAB + Substrate Chromogen System, ref: K3468, Dako, CA, USA) was used to visualize the reactions.

Negative controls, essential for validating specificity, were processed using the same protocol, omitting the primary antibody and replacing it with BSA solution. The slides were contrasted with Harris hematoxylin for 20 seconds. The sections were dehydrated in absolute ethanol, clarified in xylene, and mounted with synthetic mounting medium. Images were captured using a Leica DM6 microscope.

2.3. Determination of Pulmonary Ang I, Ang II, Ang A, Alamandine, and Ang-(1-7) by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

An aliquot of 950 μL acetone was added to 50 μL of plasma samples and shaken for 60 seconds. After centrifugation at 9,000 × g for 6 minutes, the supernatant was collected, dried under nitrogen, and resuspended in 50 μL of acetonitrile immediately before analysis.

The analytical system included a Nexera-i LC-2040C coupled with an LCMS-8045 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Electrospray ionization parameters in positive mode were set as follows: capillary voltage at 4,500 V; desolvation line temperature at 250 °C; heating block temperature at 400 °C; drying gas flow at 10 L/min; and nebulizing gas flow at 3 L/min. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) was conducted using the following fragmentation patterns. Ang I: m/z 649.10 → 110.10; 649.10 → 269.10; 649.10 → 426.25. Ang II: m/z 523.80 → 263.20; 523.80 → 70.20; 523.80 → 110.15. Ang A: m/z 501.80 → 70.10; 501.80 → 263.10; 501.80 → 110.05. Alamandine: m/z 428.45 → 110.10; 428.45 → 211.15; 428.45 → 11.10. Ang-(1-7): m/z 450.30 → 110.10; 450.30 → 70.10; 450.30 → 392.65.

Chromatographic separation was performed using an Acquity UPLC® C18 column (2.1 x 50 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) (Waters Corporation, Ireland) in gradient elution mode at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B), both fortified with 0.1% formic acid, programmed as follows: 0–0.5 min, 2% B; 0.5–3.0 min, 2–100% B; 3.0–3.5 min, 100% B; 3.5–3.8 min, 100–2% B; 3.8–8 min, 2% B. The column oven was maintained at 50 °C. Data were processed using LabSolutions software (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 7. Student’s T-test was used for statistical comparisons, and Pearson’s correlation test assessed the association between variables. All results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

Clinical data and lung tissue from 19 patients, including those with and without IPF, were assessed. The mean age was 68 years (±13) for the IPF group and 59 years (±9) for the control group (p=0.092). The IPF group included 4 males (44%), while the control group comprised 7 men (70%) (p=0.369). A significant proportion of patients were identified as white, 9 (100%) in the IPF group and 8 (80%) in the control group (p=0.156). Control group patients exhibited a normal body mass index (BMI) of 23.11 (± 4.57), whereas IPF patients were overweight, with a BMI of 25.81 (± 1.73) (p=0.100). A minority of patients were active smokers: 11% in the control group and 20% in the IPF group (p=0.999;

Table 1).

Table 2 provides a comprehensive clinical characterization of patients, offering details on continuous oxygen use, spirometric data, lung scintigraphy, echocardiography, and the 6MWT. The analysis of these results revealed that only patients in the IPF group required continuous oxygen therapy, with a prevalence of 60% (p=0.0108). Spirometric data indicated that all measured parameters were higher in the control group compared to the IPF group. The latter exhibited a moderate obstructive ventilatory disorder, with predicted forced vital capacity (FVC) at 48.72% ± 12.69 and predicted forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) at 51.29% ± 14.58 (both p<0.0001).

The echocardiogram results showed a right ventricular ejection fraction of 67.10 ± 7.34%, reflecting cardiac function, and a SPAP of 53 ± 29.89 mmHg, which is typical in IPF. Lung scintigraphy patterns carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) had a mean value of 32.83 ± 13.43. In the 6MWT assessment, the distance covered by the IPF group (393.67 ± 73.71 m) was significantly lower than the estimated distance (556.67 ± 64.97 m).

Furthermore, this analysis revealed a significant increase in heart rate (HR) (from 81.44 ± 12.47 to 120.6 ± 13.32; p<0.0001) post-test compared to pre-test results, respiratory rate (RR) (from 21.22 ± 6.77 to 37.22 ± 13.49; p=0.005), BORG index (from 0.83 ± 1.17 to 3.94 ± 2.37; p=0.002), and a decrease in oxygen saturation (SPO2) (from 96.11 ± 1.90 to 79.56 ± 6.04; p<0.0001).

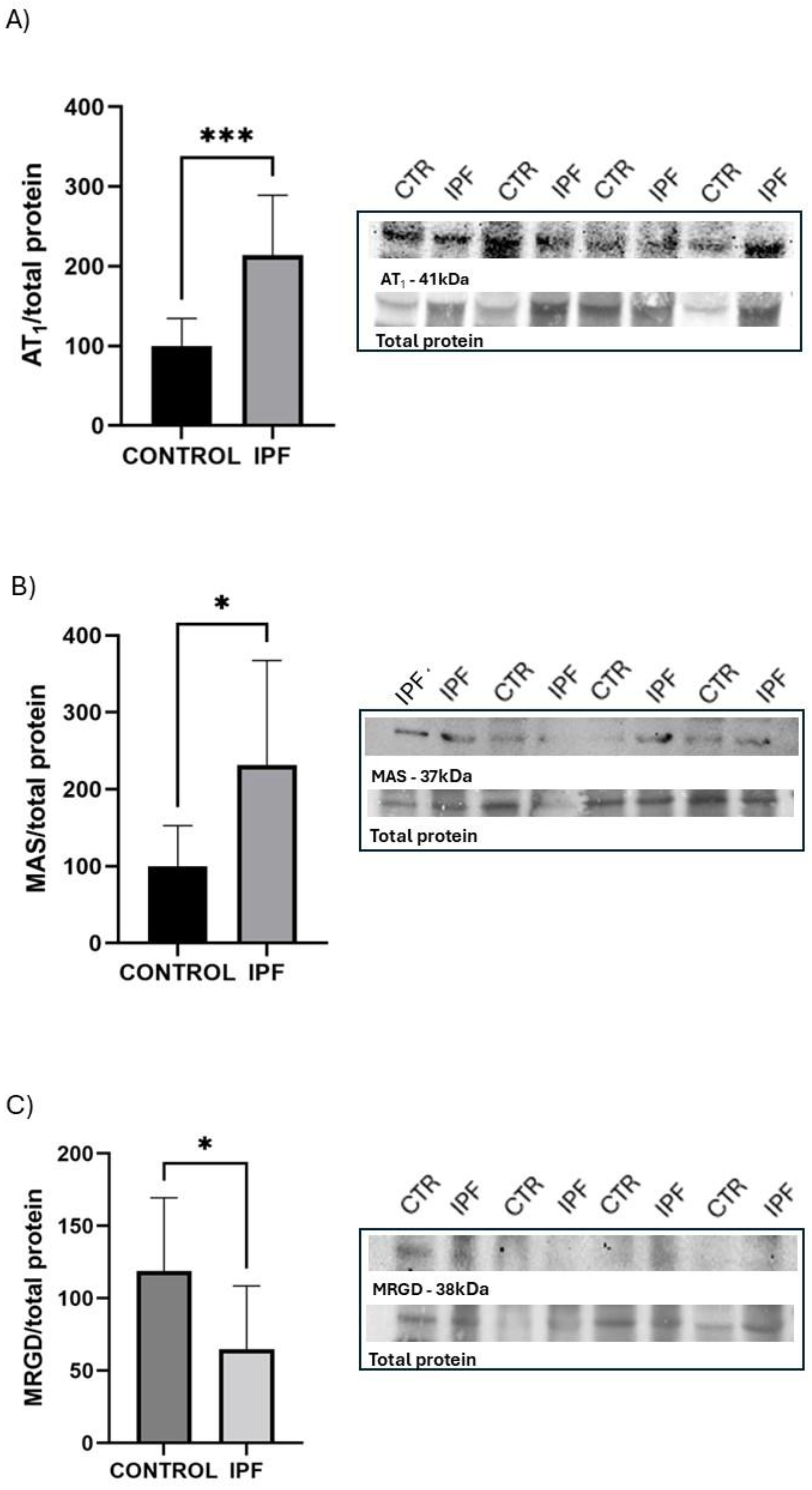

Figure 1 illustrates the protein expression of the RAS receptors in lung tissue, highlighting the protein bands and total protein levels for each receptor using the Western blot technique. The IPF group showed significantly higher protein expression of AT1 and Mas receptors, with increases of 2.13-fold and 2.31-fold, respectively, compared to the control group. Conversely, the MrgD receptor exhibited greater expression in the lung tissue of the control group, with a 1.83-fold increase compared to the IPF group.

In

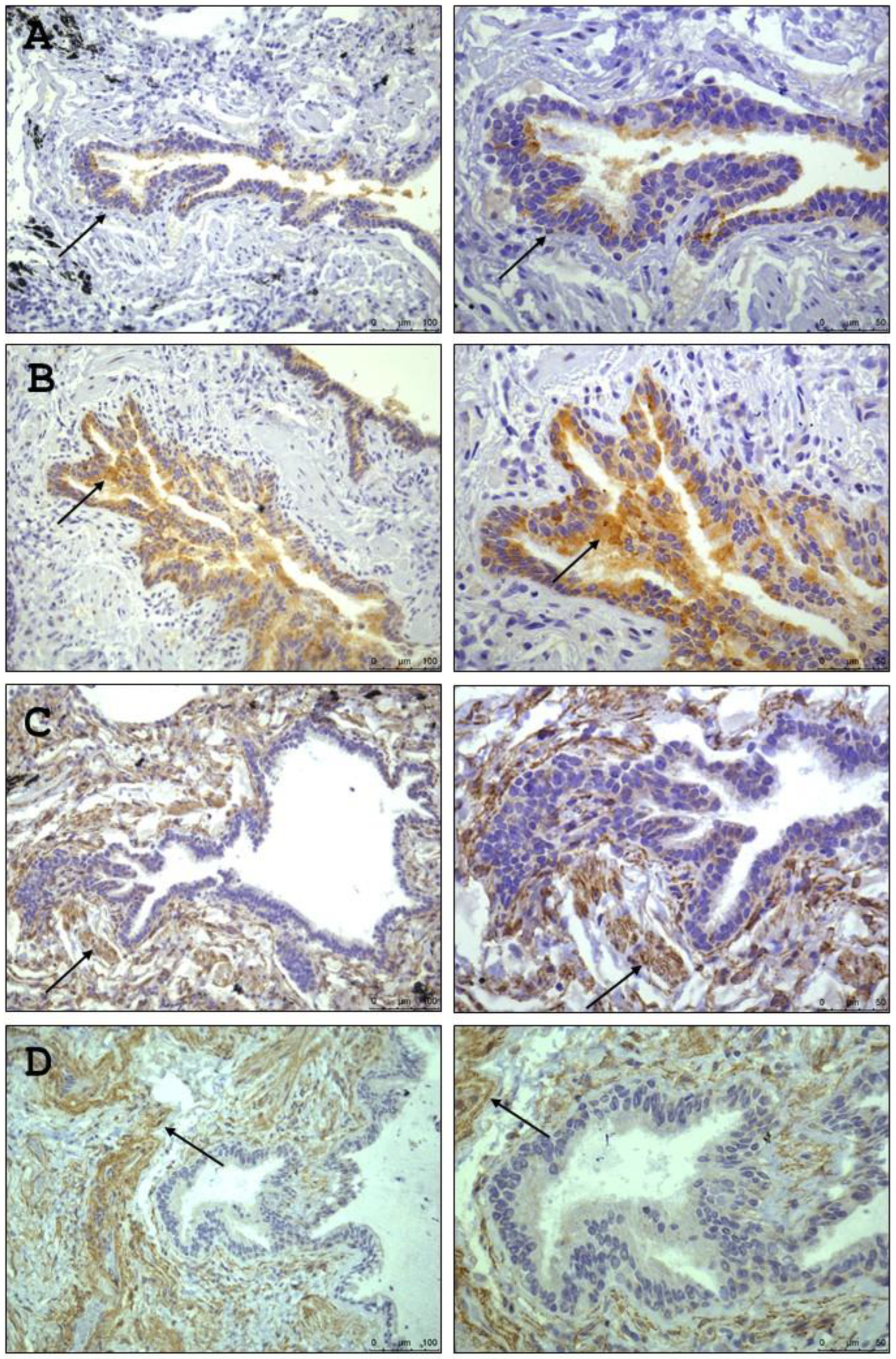

Figure 2 presents the identification of the Mas and MrgD receptors in lung tissue, specifically within the pulmonary alveoli and lung parenchyma, using the immunohistochemistry technique. However, AT1 receptor was not detectable using this method.

Table 3 provides the plasma characterization of the patients’ RAS, offering details on the peptides Ang I, Ang II, Ang A, Ang- (1-7), and ALA. Analysis of these results revealed that all measured parameters were higher in the control group compared to the IPF group, with only Ang I present statistical significance.

Correlations between clinical data and RAS peptides/receptors were performed, showing weak to moderate correlations, both positive and negative, without statistical significance. Only two correlations were statistically significant: the pre-BORG index with the Mas receptor, r = 0.679 (p < 0.05), and the ejection fraction with the AT1 receptor, r = -0.645 (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The main findings of this study are as follows: (1) the MrgD receptor is less expressed in the lung parenchyma of patients with IPF; (2) in contrast, the Mas and AT1 receptors are more highly expressed in the lungs of IPF patients; and (3) the Mas receptor is predominantly localized in the pulmonary bronchioles. Regarding the circulating components of the RAS, the plasma concentration of Ang I was significantly higher in the control group, while no significant differences were observed for Ang II, Ang-(1–7), or ALA. These findings support the concept of tissue-specific activation of the RAS, independent of the systemic circulation. Furthermore, our results align with previous findings in animal models [

20,

21] and add new evidence by demonstrating Mas receptor localization in the human lung, reinforcing its potential relevance in pulmonary fibrosis (PF) pathophysiology.

Our findings align with established epidemiological patterns of IPF prevalence [

7,

15,

16,

22]. Patients also presented higher body weight and BMI compared to controls, consistent with findings by Alakhras [

23] and Souza et al. [

24]. Although BMI values were within the range considered appropriate for older adults in Brazil (>22 to <27 kg/m

2) [

25], excess weight could potentially contribute to worsened respiratory function in these patients.

Disease severity was evidenced by altered spirometry, reduced 6MWD, and the need for continuous oxygen therapy. Most patients exhibited more severe clinical conditions than those described in other studies [

16,

22], particularly among those undergoing lung transplantation, as previously reported [

23]. In addition, the marked reduction in FEV

1 (%) and abnormalities observed on lung scintigraphy further underscore the advanced impairment of pulmonary function in our PF cohort. Consistently, previous studies have demonstrated that patients requiring continuous oxygen therapy often exhibit significant alterations in lung imaging, underscoring the urgent need for more effective therapeutic interventions.

Our 6MWT findings aligned with those of Sipriani et al. [

16], and post-test changes in HR, RR, SpO

2, and Borg scale scores confirmed impaired exercise tolerance, consistent with Morales-Blanhir et al. [

26]. This limitation contributes to a higher risk of cardiovascular complications, as also described in the literature [

27]. Moreover, patients exhibited severely reduced DLCO (≈33%) and FVC values, indicating significant functional impairment, in contrast to the expected DLCO range of 80–120% in healthy individuals [

28,

29].

Severe lung function impairment in IPF patients is confirmed by significant reductions in FEV1 and abnormal lung scintigraphy findings. Consistent with these findings, studies indicate that patients requiring continuous oxygen therapy often present significant lung scan abnormalities [

30].

Although plasma levels of angiotensin peptides—except for Ang I—did not differ significantly between IPF patients and controls, lung tissue RAS receptor expression showed a distinct local activation pattern. Specifically, the increased expression of AT1 and Mas receptors in patients with IPF indicates an upregulation of tissue-specific signaling pathways, which may suggest a localized compensatory mechanism, independent of systemic peptide concentrations.

This is consistent with prior evidence in mice showing that in fibrotic lungs, AT1 receptor expression is enhanced, promoting Transforming Growth Factor beta mediated profibrotic signaling, fibroblast proliferation, and extracellular matrix deposition [

31,

32], even when circulating Ang II levels remain unchanged [

32]. Ang II has a very short half-life in the circulation—less than 60 seconds [

33] which supports the hypothesis that it may be generated near its site of action, functioning as part of a localized RAS in various tissues [

34]. Molecular studies indicate that AT1 activation induces both rapid cellular responses and long-term genetic changes [

35]. Such findings underscore the importance of considering local receptor dynamics when interpreting the role of RAS in disease.

Furthermore, our findings align with the study by Raupp and colleagues [

15], which also reported an increase in the counter-regulatory axis involving the AT1 in the lungs of IPF patients [

15]. Known for mediating vasoconstriction and promoting fibrosis, the increased presence of AT1 receptor, along with reduced MrgD receptor expression in the parenchyma, could contribute to airway obstruction or reduced lung compliance.

Although RAS blockers have shown effects on lung tissue in patients [

36] and animal models [

37], our study highlights a divergence between local (organ-specific) and systemic RAS activities, which may explain why systemic RAS blockers have not proven clinically effective in treating IPF [

38,

39]. This concept is supported by studies demonstrating that the RAS operates both systemically and locally, with receptor expression patterns in the pulmonary vasculature and parenchyma responding to the tissue microenvironment [

40]. This suggests that there may be underlying interactions or mechanisms between the tissue-specific and plasma RAS components that remain elusive, potentially impacting the overall therapeutic outcomes.

On the other hand, the upregulation of the Mas receptor in IPF may reflect an attempt to counteract fibrotic remodeling via the Ang-(1–7)/Mas axis [

41], whereas the higher expression of MrgD receptor in control lungs—associated with Alamandine’s antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory actions—suggests a loss of this protective signaling in disease. Collectively, these findings indicate a pathological shift toward profibrotic dominance in the local RAS profile of IPF lungs, despite relatively stable systemic hormone levels.

Sipriani et al. [

16] reported ALA plasma concentrations that were four times lower in patients with IPF. This is likely to reflect the fact that the patients in that study were in an earlier stage of fibrosis, where disease progression was clearly exacerbating due to the deficiency of ALA a peptide known for its anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects. It seems that the RAS becomes increasingly unbalanced as the disease advances, potentially contributing to the worsening of fibrotic conditions. The observed reduction in hormones as reported by Sipriani [

16], combined with our findings of decreased MrgD receptor levels, indicates that this axis is significantly impaired in all stages of IPF in patients.

The distinct receptors localization found indicate specific pathophysiological roles upon stimulation. It is likely that MrgD receptors play a role in modulating gas exchange processes and influencing fibrotic responses. Conversely, the Mas receptors, located in the bronchioles, probably play a role in counteracting the airway obstruction. These roles underscore the complex interplay of these receptors in lung pathophysiology.

This rationale is confirmed in asthma [

42], where Mas receptors, predominantly located in the bronchioles and the bronchi of animals [

20,

43], may influence airway resistance and ventilation dynamics. Understanding the precise localization of receptors in humans is crucial, as it suggests that therapies targeting specific receptors could be meticulously tailored to address pulmonary functions and pathological processes. This awareness allows for more precise interventions, potentially enhancing treatment efficacy and minimizing side effects.

While our study provides valuable insights, it is important to consider certain limitations that could help guide future research. Expanding the sample size and diversity could enhance the applicability of our findings across broader populations. Additionally, longitudinal studies might offer deeper understanding into the causal relationships between receptor localization and disease progression. Exploring a wider array of RAS receptors and pathways could further elucidate the complex mechanisms at play in IPF.

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the critical importance of receptor localization within the lung tissue for understanding the pathophysiology of IPF and developing targeted therapies. The differential expression and localization of RAS receptors point to a complex interplay of local tissue dynamics that drive disease progression. Such insights highlight that therapeutic strategies must consider local receptor environments to effectively modulate pathological processes. Moreover, recognizing the distinct roles of various receptors can inform the design of tailored therapies that optimize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects.

Overall, our findings support shifting IPF treatment strategies toward targeting local RAS components encouraging development of novel, localized therapeutic agents. This approach promises to enhance our ability to manage IPF more effectively, offering patients the potential for improved outcomes and quality of life.

Author Contributions

Writing- Original draft, review and editing, supervision, sata collection and methodology (techniques), data analyses and study execution A.T.S.; Methodology (techniques), data analysis, writing and review L.S.F and G.R.G. Data analysis, writing and review, J.F and I.A.M. Data collection, analysis, writing and review, L.B.O., L.T.M.S, L.S.M. and F.A.P. Means, writing and review, M.R.W; Methodology (techniques), data analysis, writing and review, S.E.; Writing - original draft, review and editing, supervision, methodology, data analysis and means K.R.

Funding

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (process number 405252/2021-8), and Fundação Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior for a doctoral scholarship to A.T.S., J.F. and I.A.M.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre and the Irmandade Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre (Number 69947517.2.0000.5345/69947517.2.3001.5335).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank the Lung Transplantation Team at the referring institution, as well as the patients who participated in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reports in this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACE |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| ALA |

Alamandine |

| Ang-(1-7) |

Angiotensin -1-7 |

| Ang I |

Angiotensin I |

| Ang II |

Angiotensin II |

| Ang A |

Angiotensin A |

| AT1 |

Angiotensin type 1 |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| DLCO |

Carbon monoxide diffusing capacity |

| FEV1 |

Expiratory volume in first second |

| FVC |

Forced vital capacity |

| HR |

Heart rate |

| IPF |

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| MrgD |

Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptor D |

| PF |

Pulmonary fibrosis |

| RAS |

Renin-angiotensin system |

| RR |

Respiratory rate |

| SPAP |

Systolic pulmonary artery pressure |

| SPO2 |

Oxygen saturation |

| 6MWT |

6-minute walt test |

References

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Myers, J.L.; et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018, 198, e44–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, C.A.C.; Cordero, S.; Resende, A.C. Progressive fibrotic interstitial lung disease. J Bras Pneumol 2023, 49, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, B.J.; Ryter, S.W.; Rosas, I.O. Pathogenic Mechanisms Underlying Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis 2022, 17, 515–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikolasch, T.A.; Garthwaite, H.S.; Porter, J.C. Update in diagnosis and management of interstitial lung disease. Clin Med (Northfield Il) 2017, 17, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SBPT (Sociedade Brasileira Pneumologia e Tisiologia). Fibrose Pulmonar Idiopática. 2023. Available online: https://sbpt.org.br/portal/publico-geral/doencas/fibrose-pulmonar-idiopatica/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- SBPT (Sociedade Brasileira Pneumologia e Tisiologia). Fibrose Pulmonar Idiopática: o diagnóstico precoce salva vidas. 2021. Available online: https://sbpt.org.br/portal/fibrose-pulmonar-idiopatica-2021/ (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Baddini-Martinez, J.; Baldi, B.G.; da Costa, C.H.; et al. Update on diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Bras Pneumol 2015, 41, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro Pereira, C.A.; Baddini-Martinez, J.A.; Baldi, B.G.; et al. Segurança e tolerabilidade de Nintedanibe em pacientes com fibrose pulmonar idiopática no Brasil. J Bras Pneumol 2019, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottin, V.; Wollin, L.; Fischer, A.; et al. Fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: Knowns and unknowns. Eur Respir Rev 2019, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABTO (Associação Brasileira de Transplante de Órgãos). Registro Brasileiro de Transplantes n.4/2024. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Associação Brasileira de Transplante de Órgãos (ABTO). Registro Brasileiro de Transplantes. Dados Númericos da doação de órgãos e transplantes realizados por estado e instituição no período: JANEIRO / MARÇO - 2025. J: Dados Númericos da doação de órgãos e transplantes realizados por estado e instituição no período, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Marut, W.; Kavian, N.; Servettaz, A.; et al. Amelioration of Systemic Fibrosis in Mice by Angiotensin II Receptor Blockade. Arthritis Rheum 2013, 65, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Tan, Y.; Zhao, F.; et al. Angiotensin ii plays a critical role in diabetic pulmonary fibrosis most likely via activation of nadph oxidase-mediated nitrosative damage. Am J Physiol - Endocrinol Metab 2011, 301, E132–E144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautner, R.Q.; Villela, D.C.; Fraga-Silva, R.A.; et al. Discovery and characterization of alamandine: A novel component of the renin-angiotensin system. Circ Res 2013, 112, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raupp, D.; Fernandes, R.S.; Antunes, K.H.; et al. Impact of angiotensin II type 1 and G-protein-coupled Mas receptor expression on the pulmonary performance of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Peptides 2020, 133, 170384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipriani, T.S.; dos Santos, R.A.S.; Rigatto, K.; et al. The Renin-Angiotensin System: Alamandine is reduced in patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. J Cardiol Cardiovasc Med 2019, 4, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobe, J.L.; Mecca, A.P.; Lingis, M.; et al. Prevention of angiotensin II-induced cardiac remodeling by angiotensin-(1-7). Am J Physiol - Hear Circ Physiol 2007, 292, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villela, D.C.; Passos-Silva, D.G.; Santos, R.A.S. Alamandine: A new member of the angiotensin family. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2014, 23, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho Santuchi, M.; Dutra, M.F.; Vago, J.P.; et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) and Alamandine Promote Anti-inflammatory Response in Macrophages In Vitro and In Vivo. Mediators Inflamm 2019, 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, G.S.; Rodrigues-Machado, M.G.; Motta-Santos, D.; et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) attenuates airway remodelling and hyperresponsiveness in a model of chronic allergic lung inflammation. Br J Pharmacol 2015, 172, 2330–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, G.S.; Barroso, L.C.; Reis, A.C.; et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) promotes resolution of eosinophilic inflammation in an experimental model of asthma. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdán-De-las-heras, J.; Balbino, F.; Løkke, A.; et al. Effect of a new tele-rehabilitation program versus standard rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakhras, M.; Decker, P.A.; Nadrous, H.F.; et al. Body mass index and mortality in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2007, 131, 1448–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, S.M.P.; Nakasato, M.; Bruno, M.L.M.; Macedo, A. Nutritional profile of lung transplant candidates. J Bras Pneumol 2009, 35, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABESO Associação Brasileira para o Estudo da Obesidade e da Síndrome Metabólica Diretrizes brasileiras de obesidade 2016. 2016.

- Morales-Blanhir, J.J.E.; Palafox Vidal, C.D.; Rosas Romero, M.D.J.; et al. Six-minute walk test: a valuable tool for assessing pulmonary impairment. J Bras Pneumol 2011, 37, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduardo, D.S.; Gonçalves, N.T.; Garcia, L.C.C.; et al. Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on exercising tolerance in patients with advanced lung disease in waiting list for lung transplant. Rev Médica Minas Gerais 2015, 25, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, K.R.S. Measurement of diffusing capacity: interpretative strategies. Pulmão RJ 2018, 27, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, V.P.; de Miranda, D.M.; Reis, M.A.S.; et al. Reference values for the carbon monoxide diffusion (Transfer factor) in a Brazilian sample of white race. J Bras Pneumol 2019, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Hamou, Z.; Levy, N.; Charpentier, J.; et al. Use of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen and risk factors for high-flow nasal cannula oxygen failure in critically-ill patients with COVID-19. Respir Res 2022, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, B.; et al. Chronic Activation of the renin-angiotensin system induces lung fibrosis. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhal, B.D.; Li, X.; Piasecki, C.C.; Molina-Molina, M. Angiotensin signalling in pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2012, 44, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kats, J.P.; de Lannoy, L.M.; Danser, A.H.J.; et al. Angiotensin II Type 1 (AT 1 ) Receptor–Mediated Accumulation of Angiotensin II in Tissues and Its Intracellular Half-life In Vivo. Hypertension 1997, 30, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas, S.A. The Renin-Angiotensin Aldosterone System: Pathophysiological Role and Pharmacologic Inhibition. J Manag Care Pharm 2007, 13, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Iwao, H. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Angiotensin II-Mediated Cardiovascular and Renal Diseases. Pharmacol Rev 2000, 52, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Lee, E.J. Recent advances in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2013, 74, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.; Feng, D.; Wu, Q.; et al. Losartan Attenuates Ventilator-Induced Lung Injury. J Surg Res 2008, 145, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadrous, H.F.; Ryu, J.H.; Douglas, W.W.; et al. Impact of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and statins on survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2004, 126, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.T.; Wang, X.J.; Xue, C.M.; et al. The Effect of Cardiovascular Medications on Disease-Related Outcomes in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Lorenzo, O.; Rupérez, M.; et al. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in vascular diseases: Expanding the field. Hypertension 2001, 38, 1382–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, G.S.; Rodrigues-Machado, M.G.; Motta-Santos, D.; et al. Chronic allergic pulmonary inflammation is aggravated in angiotensin-(1–7) mas receptor knockout mice. Am J Physiol - Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2016, 311, L1141–L1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, K.; Ishimoto, H.; Yamada, S.; et al. Autopsy analyses in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 2014, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hashim, A.Z.; Renno, W.M.; Raghupathy, R.; et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) inhibits allergic inflammation, via the MAS1 receptor, through suppression of ERK1/2- and NF-kB-dependent pathways. Br J Pharmacol 2012, 166, 1964–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).