1. Introduction

More than one century of mobility centered on the use of private cars determined the identification of this transport modality with the “natural way” to access to services and jobs. This perspective guided the design of urban infrastructures and resulted in a large share of impervious urban surfaces devoted to motorized vehicles in the form of roadways and parking lots. Such infrastructures are responsible for several different environmental costs, such as increased storm runoff, pollution of freshwater systems, urban heat island effect, blockade of ecological corridors and are biologically inert [

1]. In USA, on average more than 20% of the urban surface is occupied by parking lots, with cities in which this number reaches 45%, namely a surface that largely exceeds that of parks and that, at the same time, is also significantly underused [

2]. Furthermore, roughly a quarter of urbanized land is taken by roadways and, also in this case, according to the cost-benefit analysis, their share seems oversized [

3]. Altogether, these data indicate that half of the urban surface is occupied by infrastructures designed mostly for cars and that these surfaces are not efficiently used. Several authors conclude that the policies focused on roadway expansion should be abandoned and the space rather used for alternative activities. Redundant roadways and car parking facilities have been identified in cities outside USA as well and their conversion is considered a major opportunity to improve the sustainability of urban areas [

4,

5,

6].

Traffic congestion, air pollution and the consequences of climate change in terms of extreme precipitations and overheating of urban areas urge re-thinking the idea of car-centered city and moving towards more sustainable formats [

7]. Cities need to reduce their impervious surfaces, multiply the greening, support active mobility and improve the life quality by increasing the environments suitable for social activities. These modifications require a reorganization of the urban space, namely a transformation of the use destination of part of it that should be taken away from cars and allocated to support functions that improve resilience. In other terms, since the space is limited and already saturated, it would be necessary to reconvert it, eliminating some infrastructures designed for car use to accommodate elements suitable for alternative fruition. In contrast to such option, the prevalent broadcasted message follows the marketing campaign of automotive industry that suggests that the mobility green revolution will be achieved by the simple substitution of private cars with internal combustion engines with others supplied by batteries. What is removed from this narrative is the hypothesis to switch from a city in which the transport is based on private cars to a more sustainable urban model in which active modes and public transport will cover most of the mobility needs. Then, since the infrastructures for such mobility model are less demanding in terms of space [

8], there is a potential net gain of urban space that would become available for further uses, such as greening.

Apart from general considerations about the energetic budget of electric cars (from where does the electric energy necessary to load the batteries come? What are the environmental and energetic costs of battery manufacturing and recycling?), the mere substitution of cars will not impact the urban space distribution and, as a consequence, will further postpone the development of infrastructures suitable for cycling and more efficient circulation of public transport as well as the recovery of public space for social/leisure activities and environmental scopes. However, even in the case of a conservative policy preserving the present mobility share, space can be gained by favoring the use of small cars with respect to large vehicles. This option would oppose the present reality, namely the trend supported by the car industry that goes in the direction of proposing bigger and bigger cars in terms of dimensions and weight, independently on the motorization type [

9,

10,

11,

12]. These vehicles occupy more space and are more dangerous as well because heavier, their bulky structure prevents the complete view of the surrounding environment to all the road users, and they favor a safety feeling in the drivers that is associated to aggressive and risky driving behavior that increases progressively together with the vehicle size [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Individual mobility is a basic right that should not collide with collective needs. This means that access restrictions should not impair reaching jobs and service centers and should not affect preferentially who is already disadvantaged because forced to live in areas badly served by public transportation. Therefore, it would be fair to conceive mobility modalities providing everybody with the same opportunities, avoiding space waste due to individual over-proportional occupancy of public soil and the accumulation of other shared social costs (congestion, noise, emissions, infrastructure building and maintenance, health) [

8]. These considerations lead to the necessity of (taxation) policies aimed at discouraging not automatically the urban use of private cars to free car-used urban space, but rather to charge progressively the vehicles that represent the major load and danger because of their physical features. Several approaches have been successfully introduced, mostly in North Europe cities, to render car driving in urban environment expensive enough to promote a modification of the mobility behavior. Nevertheless, such measures are often indiscriminate or based on motorization type, favoring new (electric) cars that are too expensive for many citizens. In several cities worldwide, gentrification is progressively pushing low-income workers towards peripheries scarcely served by public transportation, implicitly imposing to them the necessity to possess a private car to reach jobs and services, and resulting in commuting time and costs that increase faster than for middle-class employees [

18]. In Paris, in contrast to people with well-paid jobs renting accommodations in central areas, unqualified, low-income workers travel on average more than 10 Km to reach their workplace [

19] and their commuting costs can account for as much as 25% of their total income [

20].

The proposal presented here has the specificity to not target cars indiscriminately or based (only) on the contribution of their exhaust fumes to air pollution but according to their encumbrance impact, namely to their spatial footprint [

21]. Larger and heavier cars require more space on the roads as well as in the parking slots, they contribute more to the wear of infrastructures and their dimension also incrementally reduces the visibility of any person moving in the traffic, independently on the used mean. Therefore, a discouraging penalty should address this element, that here will be called “car tonnage”, and it should be highly progressive for being effective. Car tonnage is a combination of volume and weight since both factors contribute to the environmental footprint and the related cost of that specific car in terms of urban hindrance and danger.

2. Materials and Methods

Cars occupy public space that could be otherwise used for alternative scopes. To be more precise, they occupy a surface (steric hindrance that impairs another object to use that area) and a volume (visual impairment) when they move as well as when they are parked. Since cars need to park in different places at different times (working, shopping, leisure activities…), parking lots are structurally oversized and underused. Furthermore, vehicle weight contributes to pollution (emissions in the case of internal combustion engines, small particles produced by friction, mostly due to breaks and tires, in all the cases) and danger in case of accidents (high impact). Therefore, it is rational to identify approaches to disincentive the use of large

and heavy cars. Our proposal is to combine encumbrance and weight in a unique value, the “car tonnage”. This is the product of the car volume (width x length x height: vehicle 3D) for its weight. Such car tonnage value might be used to calculate a corresponding (local) fee that should cover the costs for infrastructure maintenance and retrofitting (

Table 1). Of course, the tax entity will vary according to the factor used to multiply the extrapolated car tonnage value. Since the meaning of this taxation is to charge more who exploits more urban space and public infrastructures with uselessly oversized vehicles, it makes sense to have it progressive rather than linear. Possibly, the amount should be elevated enough to induce the reduction of bulky and dangerous vehicles in the car fleet over time. Two simulations relative to six models are reported in

Table 1. In the first case, the car tonnage was simply multiplied for 10 and in this scenario the difference between highest and lowest hypothetical fees for the reference cars is less than 6-fold. When the car tonnage is multiplied for itself, the difference becomes 34-fold. Independently on the modalities to calculate the tax, the qualifying point of this proposal is that indicates a new perspective, namely considering public space/volume occupancy and danger as the major parameters for charging car ownership.

Cars are assessed according to their 3D encumbrance and weight, independently on the propeller used by their motor. Tonnage is calculated as the product of these two values and fee values can be inferred by multiplying the tonnage value for an arbitrary factor. Two examples have been proposed, in green and red, respectively. The values of encumbrance and weight reported in the table are indicative, since depend on the different setups of single models.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Urban Space (Re)Distribution

In the worst cases, the urban space occupied by roadways, streets and parking lots can reach half of the total urban surface [

2,

4] and only a minimal part of it is allocated to activities different than car driving and parking, such as sidewalks, bicycle lanes and green infrastructures. This condition is the result of a city development policy centered on private car as the almost exclusive mean responsible for individual mobility. Such land use has been challenged in several cities that decided to implement actions aimed at contesting the conventional car-centered spatial distribution and at replacing systematically a consistent portion of the space previously dedicated to motorized mobility with infrastructures for active mobility and greening [

22,

23,

24,

25]. The modification of the streetscape relies mostly on innovative street design and overall reduction of parking places that can be obtained by decreasing the demand. This objective can be approached by increasing the offer of mobility means alternative to private car through policies that promote active mobility, public transport, car sharing and the use of automated vehicles. The retrofitting of public space has been justified by the necessity to reduce traffic congestion and pollution, to improve proximity economy and ecological sustainability as well as to provide socialization opportunities [

26]. In the last years, a further major driver towards urban regeneration has been the conversion of impervious surfaces into vegetated and permeable areas obtained by de-paving parking places, as well as dismissed areas [

6,

25], to mitigate the impact of extreme weather events that cause flooding and urban heat island effects [

27,

28]. The problem for the administrations remains how to find the equilibrium among the often-colliding interests of different user groups and convince car drivers that limiting the space allocated to private vehicles will result in a net benefit for everybody. Recent strategies proposed for reducing the on-street parking places start from management optimization. They consider that the overall parking surface could be significantly decreased by better exploitation of vacant parking opportunities either in other external parking lots or in garages that are present in the same areas and often have redundant capacity. Such smarter use of the resources can be obtained by centralized car parking facilities, commercial apps and AI-powered systems designed for optimal management [

6,

29,

30,

31], all solutions that have as well the capacity to reduce idle cruising to search for available parking places [

32]. Once defined the unnecessary parking places, these can be reconverted into infrastructures for cycling and pedestrians. In addition, de-paving redundant parking provides space for green infrastructures that are requested for their positive effect on the control of stormwater and excessive heating. The resulting sponge tree-lined streets improve water infiltration and reduce significantly the amount of pollutants and sediments that otherwise enter the sewers. Furthermore, they represent as well a new source of green space at the neighborhood scale, suitable as a carrier for flora and fauna and representing an aggregation place for citizens looking for pleasant outdoor environments [

33].

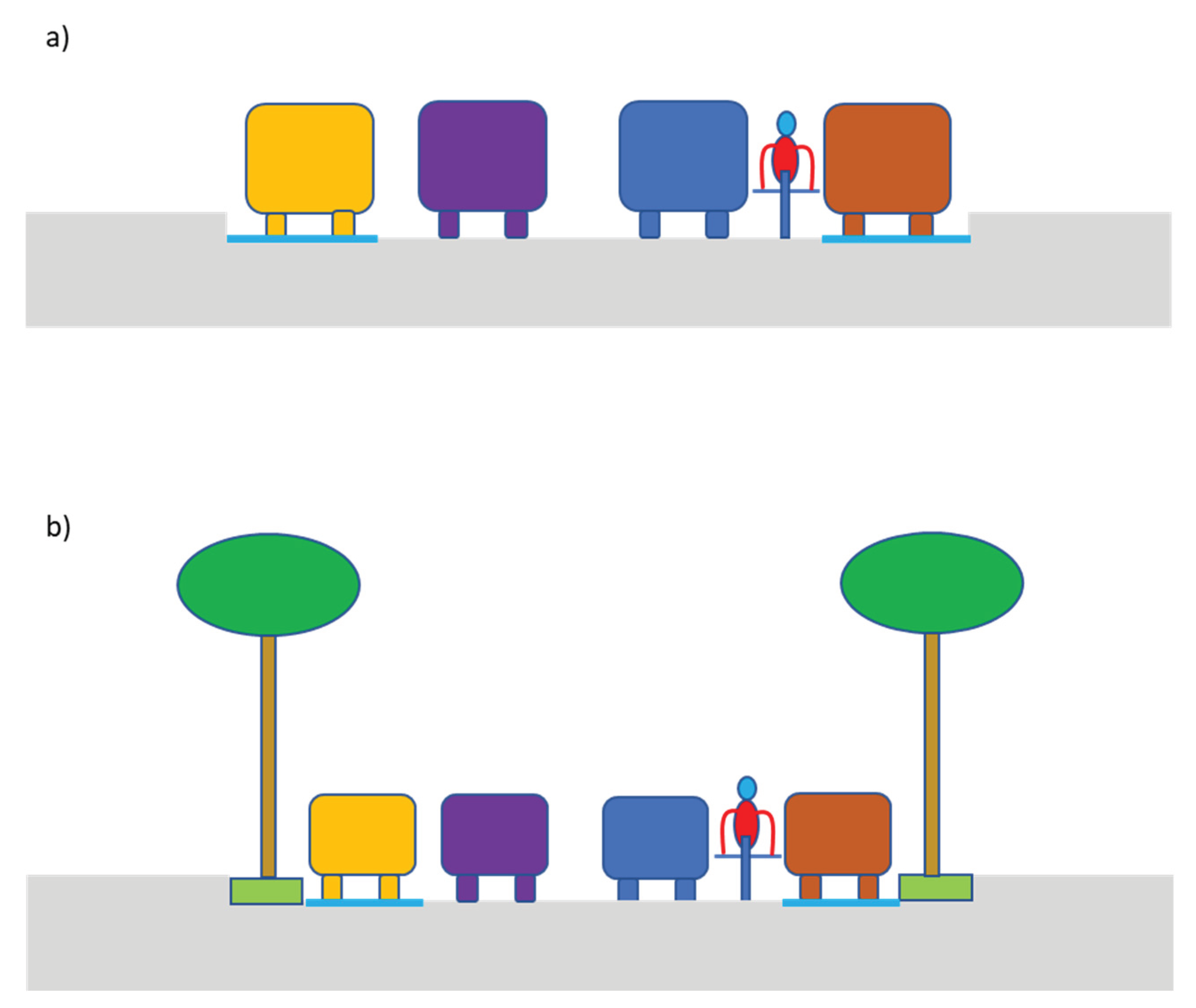

3.2. Vehicle Encumbrance and Danger

From the point of view of city sustainability, vehicles represent a double problem: when they are in movement, because generate traffic congestion, noise and pollution, and when they are stationary, because they occupy space. To be precise, the space issue is true for any vehicle, independent if stationary or in movement, but what matters is the infrastructure dimension each vehicle claims, that is proportional to its encumbrance. A thumb rule says that it is possible to allocate six to ten bicycles in the place of a single car. In Europe, the standard on-street parking place measures 2.2 x 6 m, an off-street parking place 2.5 x 5 m. These dimensions were conceived in a period in which the average car was significant smaller than nowadays. However, car shape has increased constantly in all dimensions (2 cm length/year) for all classes in the last decades, furthermore the share of extra-large vehicles such as SUV and light trucks has become higher [

9,

10,

11,

12,

21]. It means that at the present on average cars require more individual space than in the past, reason for which there are requests to increase the dimensions of single parking places, justified for instance by the necessity to reduce the high rate of accidents that happen in parking parks [

13]. Of course, accepting such logic would support the trend of using larger and larger cars. In contrast, to avoid further space to be allocated to the car pool, it would be necessary either reducing their total number or at least encouraging the substitution of large with smaller models.

The conversion of street design has an esthetical impact, since citizens appreciate streetscapes rich in trees and plants [

34], but even more relevant are probably the functional effects, as illustrated above relatively to the mitigation effect of green infrastructures. Furthermore, reducing the width of the lanes reserved to motorized vehicles to create space for greening has a direct positive impact on traffic safety because the crossing distances are shorter and the severity of the crashes significantly lower [

35,

36]. Systematic studies confirmed that there is a correlation between lane width and actual vehicle speed: specifically, users drive almost 20 Km faster when the lane pass from the minimal street width of 2.75 m to 4 m [

37]. Since the momentum of any object is given by its mass multiplied for its velocity, increased speed will determine higher momentum. This would be already an excellent reason to reduce the danger represented by vehicles by imposing roadway building design that controls velocity. The other factor determining how violent a crash will be is the mass of the objects, namely of vehicles when considering the roadway scenario. From a practical point of view, at the same velocity the momentum will increase according to the vehicle weight and this will enhance as well the distance necessary for breaking, the forces involved in a potential collision and, consequently, the overall danger. Because of their different kinetic energy, in the case of two vehicles of 1.5 and 3.0 t, both proceeding at the velocity of 50 Km/h, the distance necessary to stop will be also double (roughly 70 and 140 m, not mentioning the driver reaction time). On the top of this, heavy and imposing cars such SUV are usually also higher and this has an effect on the point of impact in the case of an accident, especially when they collide with pedestrians, cyclers or drivers of smaller cars, that results in more serious consequences [

38,

39,

40]. The conclusion is that traffic objective danger would be decreased by substituting the present fleet with lighter and smaller cars.

There is then another effect related to vehicle dimension. Safety perception is not objective and is perceived differently by the distinct traffic actors because they are dissimilarly exposed to risky conditions [

41]. Since the perception of safety is critical for the choice of riding bicycle in urban traffic, this parameter has been frequently questioned to understand what design could improve active mobility [

42,

43], but the analysis remained almost exclusively limited to the infrastructure characteristics [

44,

45]. Unluckily, these studies neglected the impact of the dimensions of the vehicles present on the roadways. For instance, their height can impair the surrounding overview that is necessary to cyclers to evaluate potential risk conditions and anticipate them. This could explain why SUV negatively affects not only congestion but also safety significantly more than smaller cars [

46]. Altogether, the literature analysis indicates that reducing the share of oversized vehicles would have multiple beneficial effects, from increased safety to reduced requirement of urban space (

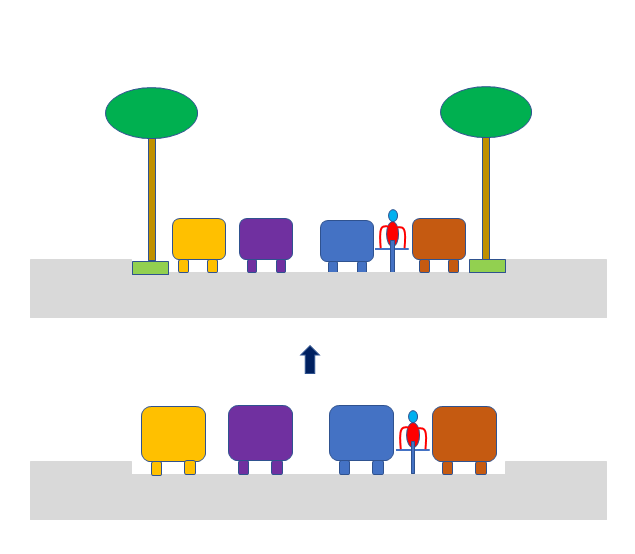

Figure 1).

3.3. Mobility-Related Disincentive Policies

Cities have long recognized that the uncontrolled use of private cars represents a major problem for traffic congestion as well as for pollution. More recently, it became evident that vehicles represent an issue for themselves, even when stationary, since they claim urban space that would be better allocated for green infrastructures and social activities. Consequently, local administrations enforced measures to reduce the access or the use of vehicles in urban areas. These measures have been designed following different strategies. Congestion tolling and on-street paid parking are the simplest to implement, since they charge any driver entering or parking in a specific area during a specific time but has been repeatedly questioned because regressive on income [

47,

48,

49]. This has to do with population, jobs and services distribution in urban regions. Despite homogeneous distribution of jobs and accommodation opportunities would be economically the most effective solution to reduce travel costs [

50], the reality usually shows a clear territorial separation of zones developed for providing alternative services. Gentrification has determined that low-income employees find housing prevalently in peripheral areas. Consequently, they have to travel longer distances and spend a consistent part of their budget for transport because they do not simply have longer commuting trips, but these very often depend on the use of private cars due to poor public transportation services in dispersed outskirts. In other words, to reach their working places low-income employees spend more for commuting than high-income citizens who can decide where to live. It means as well that the accessibility issue will affect proportionally much more their budget with respect to those who can afford living in city center and who can choose among alternative modes to organize their mobility [

51]. Therefore, it is unfair to tax who has no practicable alternatives to (often old) private car and has already transportation costs very often more elevated than housing costs [

20,

52] using the same parameter suitable for citizens who do not rely exclusively on cars for reaching the daily destinations (working places, services, leisure/socialization points). From this point of view, taxation based on the effective use of the car might turn being even more unfair, whether no alternative affordable transport opportunities are offered [

53]. Furthermore, it should be considered that not only motorization type, but also vehicle weight and velocity can strongly affect pollution and infrastructure wear. Consequently, the impact of driven distances weights differently according to the physical characteristics of the vehicle models. In this perspective, any limitation based only on theoretical exhaust production would be approximate, because it does not consider the complexity of pollutant factors. The mere replacement of polluting vehicles with internal combustion engine with electric cars has been directly or indirectly promoted by several local administrations [

54,

55]. The objective can be successfully supported by congestion pricing that excludes electric cars and can positively affect air quality [

56]. However, the conversion of old cars with new cars with greener engine technologies usually requires an investment that exclude poorer commuters and consequently also such policies tend to be regressive. Furthermore, they do not tackle the problem of wear pollution and do not consider the necessity to recover space to convert car-centered infrastructures into spaces suitable for providing higher sustainability. In general, the conventional concepts developed to control the access to cities tend to be discriminatory and address only some of the issues related to the use of the urban space. The problem represented by large and heavy cars in terms of contribution to traffic danger and congestion has been acknowledged but no explicit proposal for reducing their number has been formulated.

Since selective taxation is one of the political tools that can be exploited to promote virtuous user choices in the perspective of saving urban public space, we suggest to extrapolate a parameter, the so called “car tonnage”, that has the aim to qualify vehicles according to their encumbrance and weight, and that can be used for discouraging the use of large and heavy cars in the cities. The product of vehicle length, height and width has been already used to generate the 3D spatial footprint of a vehicle [

21] and this parameter acts as a reference for the definition of car tonnage presented here, that is arbitrary and might be formulated in other forms. What is relevant and innovative is the car tonnage concept: since the environmental costs and the overall danger of vehicles depend on both their dimension and their weight, these two elements should be quantified by an integrative factor, the “tonnage”. Furthermore, since the dimension of the vehicle produces an impact on the urban sustainability that is progressive, similarly progressive should be the disincentive effort. The tonnage calculated as the car encumbrance (3D value) multiplied for the weight can be used as the base for taxation (

Table 1). The effect would be highly progressive if the number corresponding to the tonnage would be multiplied for itself to generate the fee values. It would make sense that such taxation would be local and that the budget generated from such fees would be allocated to projects devoted to the improvement of urban conditions, from mobility infrastructure maintenance and reconversion to greening and active mobility to space recovery for social and economic activities. So far, car taxation models have generally neglected to consider the vehicle encumbrance, but some legislations already consider vehicle weight as a relevant parameter, as in the case of Japan [

57]. The rationality of this approach is supported by recent contributions that analyzed the surface and volume of car fleet and correlated these factors with traffic congestion and parking (reduced) accessibility [

21]. Since high-income generally correlates with larger and heavier cars, the solution we proposed of taxing vehicles according to their tonnage is not discriminatory towards disadvantaged workers. Resources provided by such tax could be preferentially employed to mitigate the structural weakness, in terms of access opportunities to services and jobs, that suffer the inhabitants of disadvantaged neighborhoods by improving the quality of active mobility and public transportation of those areas [

58]. Car industry has followed the trend of building larger and heavier cars [

59] with the result that it became difficult to find enough buyers [

60]. Maybe a taxation policy supporting the use of smaller vehicles might contribute to a rethinking strategy that goes behind the mere electrification of (large) models and seems anyway necessary for this industrial sector facing the crisis of the traditional symbolic dimension represented by private car [

61]. The idea of introducing a car tonnage tax has for sure a provocative component and its approval can become a major political issue, but policy makers at national level, despite the probable pressure of economic lobbies, should accept that at local level city already took a turn to guarantee their sustainability and this implies the implementation of actions that will significantly reduce the car occupancy of public space. As a consequence, also the industry should rather try anticipating this change and propose models adapted to the new reality instead of keeping on producing models that will not find anymore, literally, space in the cities of the future.

As it has been pointed out, it is time to new metrics to better quantify the private car footprint [

21] and car tonnage might represent an answer to this request for a holistic evaluation parameter. In combination with a progressive taxation scheme (

Table 1), car tonnage has the characteristics of a fair measure to disincentive the possess and use of bulky and dangerous vehicles, contributing to free urban space that could be reallocated to functions able to improve the city sustainability.

4. Conclusions

Cities that aim at becoming sustainable must reconvert their limited urban space, reducing the share devoted to car infrastructures and using the gained surfaces for active mobility, green infrastructures and social scopes. The objective of the disincentive policies implemented so far has been mainly the indiscriminate reduction of the number of cars. The aim might be meaningful but this approach is regressive in nature and consequently unequal towards citizens living in marginal areas poorly served by public transportation and who rely on private car for commuting to workplaces and for accessing to services. It would be fairer to sanction the luxury waste of space caused by big cars that serve as status symbol rather than a needful mobility mean. Since cars differ significantly in terms of dimension and weight, and such factors contribute to pollution, space occupancy and danger degree for any road user, it is rational implementing policies aimed at reducing “car tonnage”, as defined in this contribution, of vehicle fleet. Therefore, independently on the policies designed to restrict the overall number of vehicles circulating in the cities, we propose a taxation approach that favors the substitution of large with smaller cars to shrink their space requirement and improve the safety on the urban streets and roadways. The taxation based on car tonnage can be designed as highly progressive and would oppose to the present trend supported by commercial advertising that promotes the use of oversized vehicles.

Author Contributions

AdM is the only author and he took care of all the activities related to the article preparation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available at the links reported in the References.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Davis, A.Y; Pijanowsk, B.C.; Robinson, K.; Engel, B. The environmental and economic costs of sprawling parking lots in the United States. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieleszko, A. How Much of Your City Is Parking Lots? Strong Towns 2023. Available online: https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2023/9/6/how-much-of-your-city-is-parking-lots (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Guerra, E.; Duranton, G.; Ma, X. Urban roadway in America: the amount, extent, and value. J. Am. Planning Ass. 2025, 91, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Habitat. Streets as public spaces and drivers of urban prosperity. 2013. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/streets-as-public-spaces-and-drivers-of-urban-prosperity (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Furchtlehner, J.; Lehner, D.; Lička, L. Sustainable Streetscapes: Design Approaches and Examples of Viennese Practice. Sustainability 2022, 14, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croeser, T.; Garrard, G.E.; Visintin, C.; et al. Finding space for nature in cities: the considerable potential of redundant car parking. npj Urban Sustain 2022, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UBA—Umweltbundesamt. Die Stadt von Morgen: Umweltschonend Mobil—Lärmarm—Grün—Kompakt—Durchmischt, 2nd ed.; Umweltbundesamt: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2017; ISSN 2363832X. [Google Scholar]

- Vanpee, R.; Van Zeebroeck, B. A comparative cost-benefit analysis of cycling within the Benelux and North Rhine-Westphalia. 2022. Available online: https://gouvernement.lu/dam-assets/documents/actualites/2022/11-novembre/28-feuille-de-route-velo/report-cycling-benelux-executive-summary.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Molker, H. Failure prediction of orthotropic Non-Crimp Fabric reinforced composite materials. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303313423_Failure_prediction_of_orthotropic_Non-Crimp_Fabric_reinforced_composite_materials_Licentiate_thesis (accessed on June 28 2025).

- Ritchie, H. Sustainability by numbers. 2023. Available online: https://www.sustainabilitybynumbers.com/p/weighty-issue-of-electric-cars#footnote-2-134996931.

- Teoalida. Study: car evolution trends. 2023. https://www.teoalida.com/cardatabase/evolution/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Carlson, R.; Dadashzadeh, N. ; Ekmekci; M. An investigation into the relationship between car weight and fatal collision rates in the UK. 2025. Available at: https://www.ftvg.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/UK-Car-Weight-Prelim-Findings-2-Pager.pdf. (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- https://pwcattorneys.com/where-do-most-road-accidents-happen-insights-statistics/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Wenzel, T.P.; Ross, M. The effects of vehicle models and driver behavior on risk. Acc. Anal. Prevent. 2005, 37, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallner, P.; Wanka, A.; Hutter, H.P. SUV driving “masculinizes” risk behavior in females: a public health challenge. Wien Klin. Wochenschr. 2017, 129, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Choudhary, P.; Parida, M. Examining risky driving behaviours: A comparative analysis of SUVs and other car types. Transport Policy 2024, 152, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steren, A.; Rosenzweig, S.; Rubin, O.D. Is vehicle weight associated with risky driving behavior? Analysis of complete national records. Marketing Lett. 2025, 36, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneebone, E.; Holmes, N. The growing distance between people and jobs in metropolitan America. 2015. Metropolitan Policy Program at Brooking, Washington.

- Orfeuil, J.P. Déplacements, énergie consommée et formes urbaines. 2005. Available online: http://urbanisme.u-pec.fr/documentation/articles-rapports-notes/mobilite-et-transport-209910.kjsp (accessed on 12 February 2016).

- Orfeuil, J.P. Déplacements et inégalités. 2006. Available online: http://urbanisme.u-pec.fr/documentation/articles-rapports-notes/mobilite-et-transport-209910.kjsp (accessed on 12 February 2016).

- Morency, C.; Bourdeau, J.-S. Spatial and Energy footprints of Cars in Cities: New Metrics and Illustrations for the Montreal Area. Transport. Res. Procedia 2025, 82, 3589–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Copenhagen. CPH 2025 Climate Plan: A Green, Smart and Carbon Neutral City. 2012. City of Copenhagen, Technical and Environmental Administration: Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Oslo Kommune. The Car-Free Liveability Programme 2019. 2019. Oslo, Norway.

- City of Stockholm. Environment Programme 2020–2023. 2020. City Executive Office: Stockholm, Sweden.

- City of Paris. Le Bois de Charonne, un nouveau parc le long de la Petite Ceinture. 2024. Available online at: https://mairie20.paris.fr/pages/un-nouveau-parc-dans-le-20e-le-long-de-la-petite-ceinture-22485 (accessed 5 August 2025).

- Gössling, S. Why cities need to take road space from cars - and how this could be done. J. Urban Design 2020, 25, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B.A.; Coutts, A.M.; Livesley, S.J.; Harris, R.J.; Hunter, A.M.; Williams, N.S.G. Planning for cooler cities: A framework to prioritise green infrastructure to mitigate high temperatures in urban landscapes. Landscape Urban Planning 2015, 134, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marando, F.; Heris, M.P.; Zulian, G.; Udías, A.; Mentaschi, L.; Chrysoulakis, N.; Parastatidis, D.; Maes, J. Urban heat island mitigation by green infrastructure in European Functional Urban Areas. Sustainable Cities Society 2022, 77, 103564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barter, P.A. Off-street parking policy surprises in Asian cities. Cities 2012, 29, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.E. Free parking for free people: German road laws and rights as constraints on local car parking management. Transp. Policy 2021, 101, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalini, M.K. , Hanumanthappa J., K.S. Santhosh Kumar, S.P. Shiva Prakash. AI-Powered Hybrid Smart Parking: Optimizing Parking Management Across Diverse Applications in Smart Cities. Procedia Computer Sci. 2025, 258, 1524–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ommeren, J.N.; Wentink, D.; Rietveld, P. Empirical evidence on cruising for parking. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2012, 46, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J. Green Streets to Serve Urban Sustainability: Benefits and Typology. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Copenhagen. More People to Walk More: The Pedestrian Strategy of Copenhagen; The Municipality of Copenhagen, Technical and Environmental Administration: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- NACTO—National Association of City Transportation Officials. Global Designing Cities Initiative. In Global Street Design Guide, 1st ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; ISBN 978161091. [Google Scholar]

- Azin, B.; Ewing, R.; Yang, W.; Promy, N.S.; Kalantari, H.A.; Tabassum, N. Urban Arterial Lane Width Versus Speed and Crash Rates: A Comprehensive Study of Road Safety. Sustainability 2025, 17, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K.; Carlson, P.; Brewer, M.; Wooldridge, M. design factors that affect driver speed on suburban arterials. Transport. Res. Record 2000, 1751, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyndall, J. Pedestrian deaths and large vehicles. Econom. Transport. 2021, 26-27, 100219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranjan, A.; SUVs drive trend for new cars to grow 1cm wider in UK and EU every two years, says report. The Guardian 2024. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2024/jan/22/cars-growing-wider-europe-report (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Robinson, E.; Edwards, P.; Laverty, A. Do sports utility vehicles (SUVs) and light truck vehicles (LTVs) cause more severe injuries to pedestrians and cyclists than passenger cars in the case of a crash? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Inj Prev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stülpnagel, R.; Rintelen, H. A matter of space and perspective – Cyclists’, car drivers’, and pedestrians’ assumptions about subjective safety in shared traffic situations. Transport. Res. Part A 2024, 179, 103941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duren, M.; Corrigan, B.; Kennedy, R.D.; Pollack Porter, K.M.; Ehsani, J. Identifying and Assessing Perceived Cycling Safety Components. Safety 2023, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uijtdewilligen, T.; Ulak, M.B.; Wijlhuizen, G.J.; Geurs, K.T. Exploring the relationship between cyclists’ perceived unsafety, crash risk, and exposure in Dutch cities. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 219, 108113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, W. Perception of Safety and Cycling Behaviour on Varying Street Typologies: Opportunities for Behavioural Economics and Design. Transport Res. Procedia 2019, 41, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhong, C.; Suel, E. Unpacking the perceived cycling safety of road environment using street view imagery and cycle accident data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 205, 107677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahiri, M.; Chen, X. Measuring the passenger car equivalent of small cars and SUV on rainy and sunny days. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, J. Is congestion pricing fair? Consumer and citizen perspectives on equity effects. Transport Pol. 2016, 55, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krol, R. Tolling the Freeway: Congestion Pricing and the Economics of Managing traffic. 2016. Mercatus Research. Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA.

- Albalate, D.; Gragera, A. The impact of curbside parking regulations on car ownership. Regional Sci. Urban Econ. 2020, 81, 103518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, W.C. Commuting, congestion, and employment dispersal in cities with mixed land use. J. Urban Econ. 2004, 55, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Cities on the move: a world bank urban transport strategy review. 2002. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The World Bank. Washington.

- Lipman, B. A heavy load: the combined housing and transportation bur-dens of working families. 2006. Center for Housing Policy – The Library of Congress US. Washington.

- Ke, Y.; Gkritza, K. Income and spatial distributional effects of a congestion tax: A hypothetical case of Oregon. Transport Pol. 2018, 71, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oslo Kommune. Climate and Energy Strategy for Oslo. 2016. Oslo, Norway.

- Sun, C.; Xu, S.; Yang, M.; Gong, X. Urban traffic regulation and air pollution: A case study of urban motor vehicle restriction policy. Energy Policy. 2022, 163, 112819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksen, E.T.; Johansen, B.G. Congestion pricing with electric vehicle exemptions: Car-ownership effects and other behavioral adjustments. J. Environ. Economics Management. 2025, 131, 103154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Japan. Ministry of the Environment. Available online at: https://www.env.go.jp/en/policy/tax/auto/ch3.html (accessed 5 August 2025).

- Cordera, R.; Nogués, S.; González-González, E.; dell’Olio, L. Intra-Urban Spatial Disparities in User Satisfaction with Public Transport Services. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Growing preference for SUVs challenges emissions reductions in passenger car market. 2019. Available at: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/growing-preference-for-suvs-challenges-emissions-reductions-in-passenger-car-market. (accessed 11 August 2025).

- Carbonaro, G. Americans Can No Longer Afford Their Cars. Newsweek on line 2024. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/americans-can-no-longer-afford-their-cars-1859929 (accessed 11 August 2025).

- Gössling, S. Why cities need to take road space from cars – and how this could be done. J. Urban Design. 2020, 25, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).