1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a non-invasive technique for recording the brain’s electrical activity via scalp electrodes, typically arranged using standardized systems such as the International 10–20 method [

1,

2,

3]. While EEG has been widely used for identifying and reconstructing static, two-dimensional images, recent advances in generative artificial intelligence (AI) have enabled the transformation of 2D images into dynamic movies and three-dimensional objects [

4,

5]. However, most EEG-based image reconstruction efforts have focused on static images with limited categories, overlooking the dynamic nature of real-world objects and scenes [

6]. In this study, we collected EEG data from healthy volunteers using a low-cost OpenBCI headset as they viewed images of the same objects at different time points. We employed a modified one-versus-rest classifier to distinguish objects not only between categories but also across different temporal presentations. By encoding static images as chronological sequences, our approach leverages AI to reconstruct movies from EEG data and enables the identification and 3D conversion of single objects at specific time points. Decoding distinctive, sequential states of the same object from EEG on low-cost, open-source hardware could improve the accessibility of uses in art, animation, transportation, manufacturing, research, and medicine. This integration of low-cost EEG and AI has the potential to lower barriers for digital reconstruction of imagined sequences and physical realization through 3D printing, expanding the possibilities for brain-computer interface (BCI) applications [

4,

5,

6,

7].

1.2. Background

1.2.1. Summary

In EEG-based BCI has existed for decades, ranging in scope and purpose [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Earlier work converted EEG to image through encoding 1D temporal data with 2D images [

12,

13]. Recent work demonstrated the capability to convert EEG into images in real time, but requiring specialized systems and complex AI models [

6]. Others have even reported on object retrieval, leveraging synergies in verbal and visual processing [

4,

14,

15,

16]. AI has also been used to convert images into videos and 3D objects. However, the prerequisite required encoding EEG to images, often with expensive EEG systems and requiring an intense software backend [

4,

17,

18].

1.2.2. EEG to Image

The extraction of 3D models from remembered images using electroencephalography (EEG) has garnered significant attention in recent years. Researchers have made notable strides in decoding neural signals to reconstruct visual stimuli, leveraging various methodologies and technologies, especially as they pertain to the nuanced nature of human perception.

Image “reconstruction” from EEG has referred in the literature for both encoding patterns of EEG, often corresponding to specific visual images, to attempts at reconstructing images without prior prompts [

19,

20,

21]. While certain overlap exists in the literature, EEG patterns associated with visual recall generate consistently identifiable features [

22,

23,

24,

25]. If an image can be recalled and “encoded” with EEG, then it may be converted to a 3D object or image.

Wakita et al. demonstrate the reconstruction of visual textures from EEG signals, effectively utilizing spatially global image statistics in this process. Their work builds on research that outlines how EEG patterns correlate with texture perception, thus establishing a foundation for reconstructive approaches that can be adapted to encompass more complex images, including 3D models [

26]. Moreover, Ling et al. highlight the ability of EEG signals to support fine-grained visual representations, confirming methodologies applicable to image reconstruction processes, particularly with visual stimuli like words and faces [

27,

28].

The complexity of EEG signals necessitates sophisticated modeling techniques for effective image reconstruction. For instance, the work by Fuad and Taib, although focusing primarily on brainwave patterns, underscores the necessity of understanding EEG data relationships in image processing tasks. However, it's important to note that their research does not directly address 3D reconstructions [

29]. Similarly, the integration of advanced neural networks such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) has been explored. Khaleghi et al. propose a geometric deep network-based GAN that associates EEG signals with visual saliency maps, suggesting methodologies that could be extended for reconstructing 3D visual information from remembered images [

30]. These 2D to 3D conversion techniques, such as depth map estimation, were also used in photogrammetry [

31].

Additional research by Nemrodov et al. showcases the reconstruction of faces from EEG data, emphasizing EEG's potential for gaining insights into processing dynamic visual stimuli, thus indicating a progression towards more complex 3D interpretations [

32]. This highlights the advancements towards utilizing EEG not just for static images but for complex scenarios requiring 3D representations.

Ongoing developments in models that leverage variational inference for image generation from EEG data, as presented by Yang and Liu, indicate a burgeoning interest in employing diffusion models alongside conventional neural networks. Their innovative framework addresses the high-dimensional nature of EEG signals, potentially leading to credible 3D reconstructions from brain activity [

5]. On the other hand, Acar et al. emphasize the integration of head tissue conductivity estimations with EEG source localization, underlining the importance of physiological modeling in improving the accuracy of reconstructed visual outputs [

1].

1.2.3. EEG to Video

The evolution of reconstructing movies from brain activity measured through EEG is an area of growing research interest, driven by advancements in signal processing and machine learning. EEG provides superior temporal resolution relative to other imaging modalities like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which is pivotal for capturing the dynamic nature of movie stimuli. Previous findings indicate that EEG can effectively decode visual stimuli, making it a promising candidate for movie reconstruction, although challenges remain regarding noise and signal alignment [

27,

32].

A well-defined area of visual memory is sequence memory, recording EEG during a presentation of consecutive images or other stimuli. The encoding period can be as short as 200-400 ms, and distinctive EEG is generated during image recall [

22,

25,

33]. Notably, separate brain regions recalling sequential images activate in the order they were first observed. The EEG corresponding to each recalled phase in the sequence has been consistent enough to characterize [

24]. This “slideshow” may be applicable to dynamic visual stimuli.

Recent studies by Ling et al. and Nemrodov et al. highlight the potential for extending existing EEG-based image reconstruction techniques to dynamic visual stimuli. These studies emphasize that while much work has focused on static images or specific types of visual stimuli, the methodologies could be adapted to reconstruct short movie segments by leveraging the temporal dynamics that EEG can capture [

27,

32]. This opens new avenues for utilizing EEG in creating more immersive and interactive BCIs, potentially applying real-time feedback loops to enrich the user experience during movie screenings [

34,

35].

Innovative algorithms, such as those proposed by Khaleghi et al. and Yang and Liu, employ generative models to synthesize images from EEG signals [

5,

30]. The geometric deep network-based generative adversarial network (GDN-GAN) introduces a method that emphasizes visual stimuli saliency while leveraging deep learning frameworks to achieve higher fidelity in reconstructions. Yang and Liu's EEG-ConDiffusion framework exemplifies a structured approach to image generation through a pipeline that addresses the inherent complexities of EEG data [

5,

30]. Moreover, works by Shimizu and Srinivasan demonstrate that combining perceptual and imaginative tasks improves reconstruction accuracy, suggesting that a multifaceted approach may be pivotal in refining reconstruction methodologies [

13].

Wang et al. and Shen et al. provide insights into using generative models to align EEG data with visual stimuli more precisely. Their research illustrates the integration of neural activity data to better facilitate the representation of visual experience during movie watching, thus accentuating the correlation between the viewer's cognitive activity and reconstructed content [

36,

37]. The implications of using EEG for such purposes lie not only in advancing neuroscience but also in enhancing technologies like virtual and augmented reality, where understanding and predicting user responses can lead to more engaging experiences.

Despite the promising advancements, challenges remain in achieving reliable synchronization between reconstructed images and the cognitive experiences they intend to represent. Issues related to noise, signal interference, and individual variations in brain activity necessitate ongoing research to refine these methods further. The integration of multidisciplinary approaches, encompassing advanced machine learning techniques and cognitive neuroscience, appears essential for overcoming these limitations and enhancing the quality of reconstructions from EEG data.

In conclusion, the current landscape of reconstructing movies from EEG signals demonstrates a blend of established techniques and cutting-edge innovations. As the field progresses, it is likely that prospective applications will emerge, ranging from entertainment to therapeutic settings, while significantly enhancing our understanding of brain function related to visual processing.

1.2.4. EEG to Object

In recent years, the integration of EEG with methods for reconstructing three-dimensional (3D) objects has gained significant attention within the research community. The fundamental challenge of reconstructing 3D objects from EEG data rests in deciphering the spatiotemporal neural activity that corresponds to visual stimuli or user interactions, and recent advancements show promising approaches in improving the accuracy and effectiveness of these reconstructions.

EEG-based 3D reconstruction systems often employ high-density electrode montages to enhance the spatial resolution of the neural signals. Taberna et al. highlighted the importance of accurate electrode localization for reliable brain imaging, suggesting that their developed 3D scanning method can significantly contribute to improving EEG's usability as a brain imaging tool, hence aiding in the spatial contextualization of neural data [

38]. Complementary to this, Clausner et al. proposed a photogrammetry-based approach that utilizes standard digital cameras to accurately localize EEG electrodes. This method not only surpasses traditional electromagnetic digitization techniques in terms of efficiency but also facilitates better integration with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for source analysis [

39].

The reconstruction process can benefit significantly from advanced machine learning techniques, particularly deep learning architectures such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs). For instance, Yang et al. introduced a generative adversarial learning framework (3D-RecGAN) designed for inferring complete 3D structures from single depth views. This approach leverages the strengths of autoencoders and generative models, thereby enhancing the detail and accuracy of the reconstructed objects, although this research did not directly correlate with EEG data [

31]. Furthermore, advancements in CNN architectures demonstrate the ability to effectively integrate multi-dimensional EEG data, yielding superior performance in decoding tasks relevant to object recognition and manipulation [

33,

40].

Additionally, studies have explored using EEG data to reconstruct visual stimuli by analyzing the neural correlates of visual perception. The work by Nemrodov et al. emphasizes the potential of using EEG in conjunction with advanced image reconstruction techniques to recover dynamic visual stimuli. Their findings support the premise that the temporal resolution of EEG might enable effective reconstruction of dynamic visual information, which could also be applicable in real-time object recognition and tracking scenarios [

32].

Overall, the fusion of EEG datasets with sophisticated image reconstruction techniques shows promise for advancing our understanding of the neural underpinnings of visual cognition and the generation of 3D models. While significant challenges remain in ensuring accuracy and real-time processing capabilities, ongoing research is striving to refine these methods. As the technology progresses, we may witness a broader application of EEG-based 3D reconstructions in both clinical and cognitive neuroscience domains.

1.2.5. Prior Work

The reconstruction and processing of remembered images using low-cost, open-source EEG offers several advantages that significantly enhance research capabilities and accessibility for broader applications. One primary benefit is the economic viability of such systems, which democratizes access to brain imaging technologies. Historically, advanced EEG setups are expensive and complex, limiting their use primarily to well-funded research institutions. The advent of open-source EEG platforms, such as OpenBCI and Creamino, provides an affordable alternative that maintains compatibility with existing software frameworks, thus enabling new research avenues and educational applications at lower costs [

14,

41].

Using low-cost EEG systems for reconstructing remembered images enhances the scalability of research studies focusing on cognitive processes such as memory recall. The integration of innovative machine learning models with EEG data can effectively decode the neural correlates associated with visual memory. For instance, advancements in computational algorithms and open-source software frameworks illustrates how researchers can tailor their analyses and improve data handling through accessible technological solutions, allowing for sophisticated and reproducible research designs [

42,

43,

44]. Furthermore, systems that facilitate real-time data processing enhance interactive research applications and brain-computer interfaces, contributing to fields ranging from psychology to robotics [

2].

The ability to conduct experiments with high temporal resolution using portable EEG systems is particularly advantageous in studying dynamic cognitive phenomena, such as the spatiotemporal trajectories inherent in visual object recall [

45]. Research demonstrates that EEG can reveal rapid neural responses and patterns associated with memory reactivation during active recall or visual imagery tasks [

46,

47]. Early findings underscore the potential of utilizing such methodologies to further explore brain functions related to memory and cognition, pushing the boundaries of our understanding of the human brain [

48].

In summary, low-cost, open-source EEG systems serve as pivotal tools in reconstructing remembered images, providing significant benefits in terms of accessibility, cost-effectiveness, scalability, and collaborative research practices. Future studies utilizing these technologies are well-positioned to deepen our understanding of neural mechanisms linked to memory recall, paving the way for advances in both scientific knowledge and applicable technology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

The deployment of an EEG-based image identification system necessitated careful consideration of stimulus selection, signal acquisition, feature extraction, and classification algorithms. During data collection, each participant was instructed to visually and aurally engage with the presented stimuli while EEG signals were recorded. Data acquisition was conducted using an OpenBCI EEG headset in conjunction with a Cyton board and OpenBCI acquisition software (OpenBCI Foundation, New York). Feature extraction focused on identifying the most robust EEG signatures associated with visual recall, informed by existing literature. For classification, a model was selected based on its ability to achieve high accuracy while minimizing overfitting. The overall system design leveraged validated methodologies from prior research to maximize reliability and performance [

27,

45,

49].

2.2. Participants

A total of 20 adult participants (mean age = 24.3 ± 4.2 years; 4 females, 16 males) were recruited during Summer 2025 via word-of-mouth and printed flyers. Eligibility criteria included age between 18 and 40 years, normal hearing, and normal or corrected-to-normal vision. All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with IRB approval (STUDY20250042). Participants were seated at a standardized distance of at least 24 inches (61 cm) from the display monitor. Following consent, the experimenter fitted each participant with a standard EEG cap and attached the reference electrode. Experimental instructions were presented onscreen, and EEG data acquisition commenced immediately thereafter.

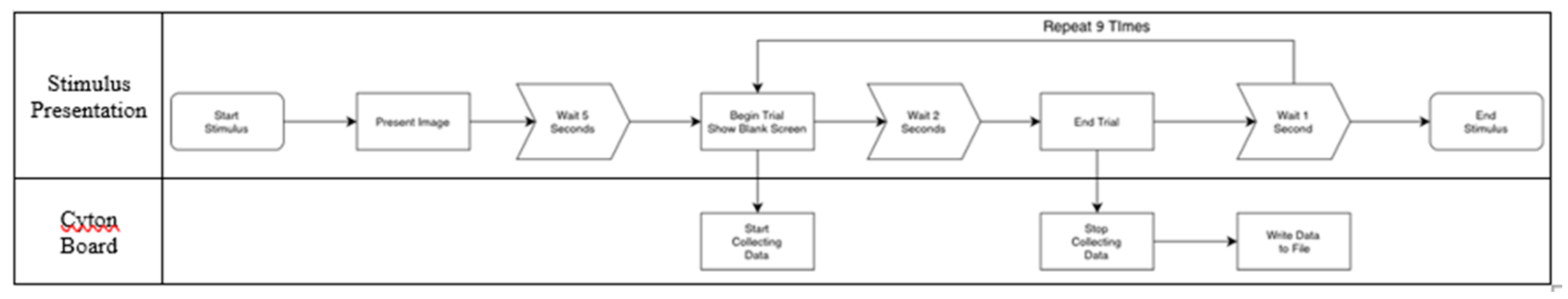

2.3. Stimulus Presentation

All software was implemented in Python [

50]. Prior EEG-based image reconstruction implementations used visual stimuli in generating training data [

4,

12,

49]. To implement temporal encoding, images depicting the same object at distinct, visually recognizable timepoints (e.g., a ship progressing along a river) were arranged in sequential pairs. The protocol ensured that the six images representing the "initial" state were always presented prior to the six corresponding "later" state images. The full chronological sequence of stimuli is illustrated in

Figure 1, while the OpenBCI Cyton board command protocol is detailed in

Figure 2.

For each image, data acquisition comprised a single demonstration phase followed by ten experimental trials. During the demonstration, a stimulus consisting of a white background with black characters was displayed for 4 seconds. Subsequently, a 1-second “wait” screen was presented, followed by a 2-second blank screen, during which participants were instructed to retain the image in memory. Another 1-second “wait” screen was interleaved after the blank interval. This fixed sequence was repeated for a total of ten trials per image. Each session encompassed ten trials of 12 unique images presented in pseudo-random order, with “initial state” images consistently preceding their corresponding “later state” versions. The total duration of each session was approximately 20 minutes, and only a single session was recorded per participant. If it was not possible to complete the entire session, as much data as possible was collected. Data were excluded from analysis if a complete set of trials for all images was not obtained.

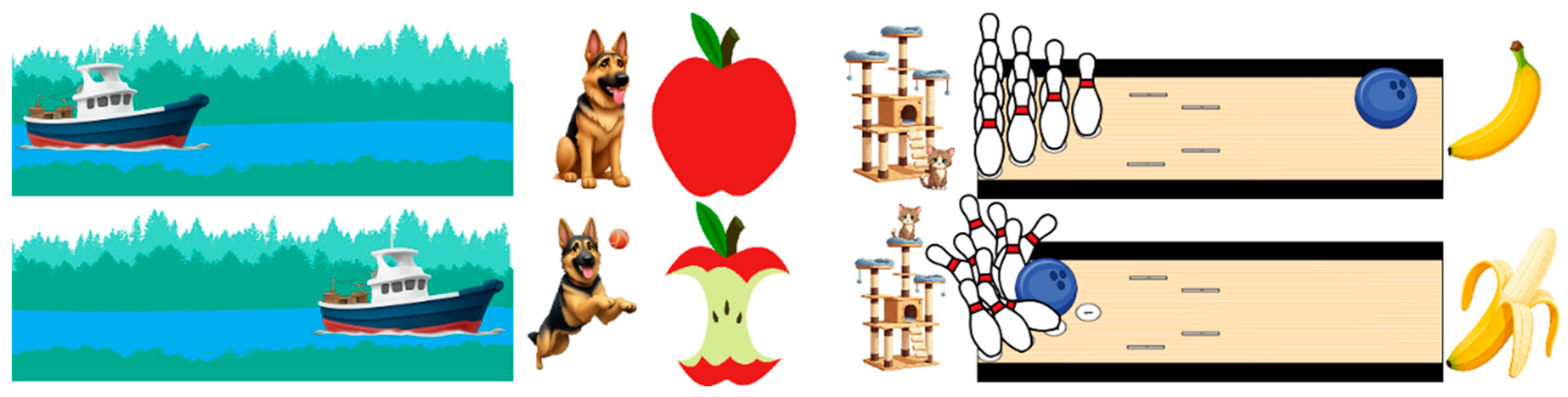

2.4. Image Processing

The images used are shown in

Figure 3. Each image was encoded with an integer from 1-12. The first “initial state” images (1-6) were always displayed before the “later state” images (7-12). The inception score was used to ensure quality outcomes [

51].

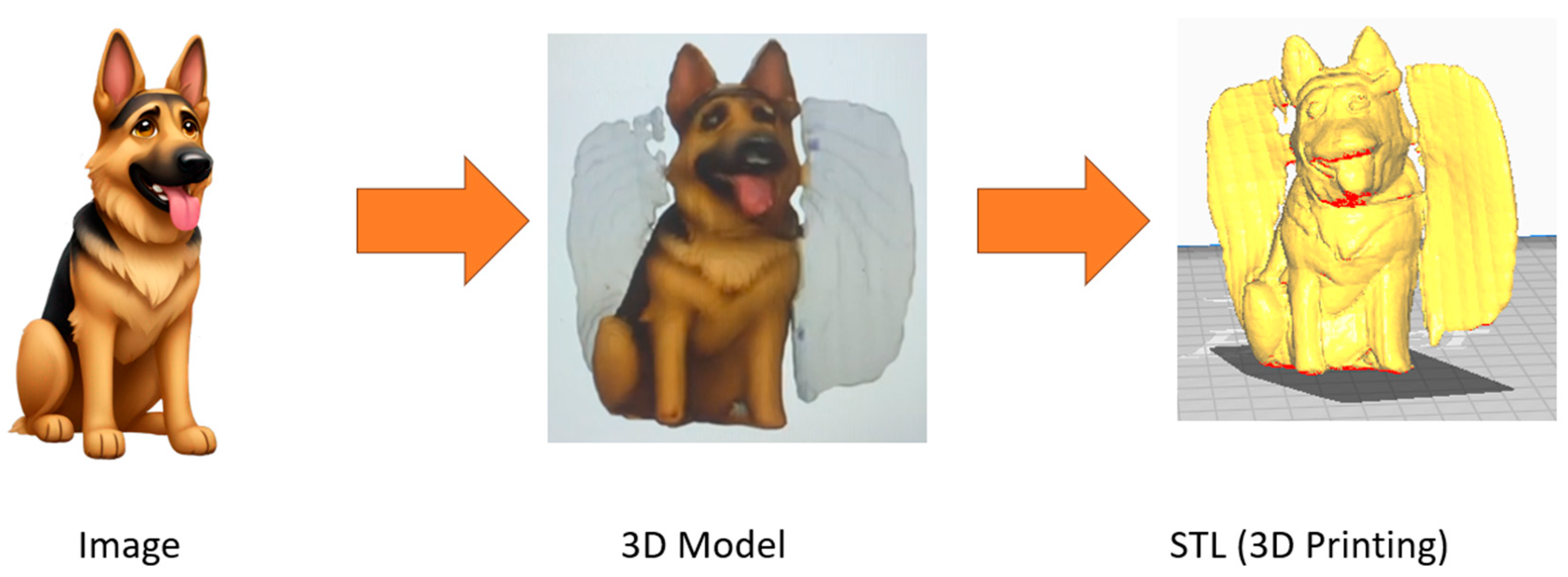

After classification, the image was sent to a pipeline prepared using ComfyUI [

52]. Each image was combined with its pair (e.g., between the “initial state” and “later state) and animated. The conversion of two sequential images to an animation has been used well before generative AI, but ComfyUI enables a generative solution for it [

52]. before A parallel pipeline converted the image to a 3D solid, corresponding to OBJ format. As detailed in prior work, the use of ComfyUI to convert 2D to 3D started with the ComfyUI-Hunyuan3DWrapper and ComfyUI-Y7-SBS-2Dto3D, which employed depth map estimation and related photogrammetric techniques [

52]. From OBJ format, each 3D model was converted to an STL file for 3D printing using Python.

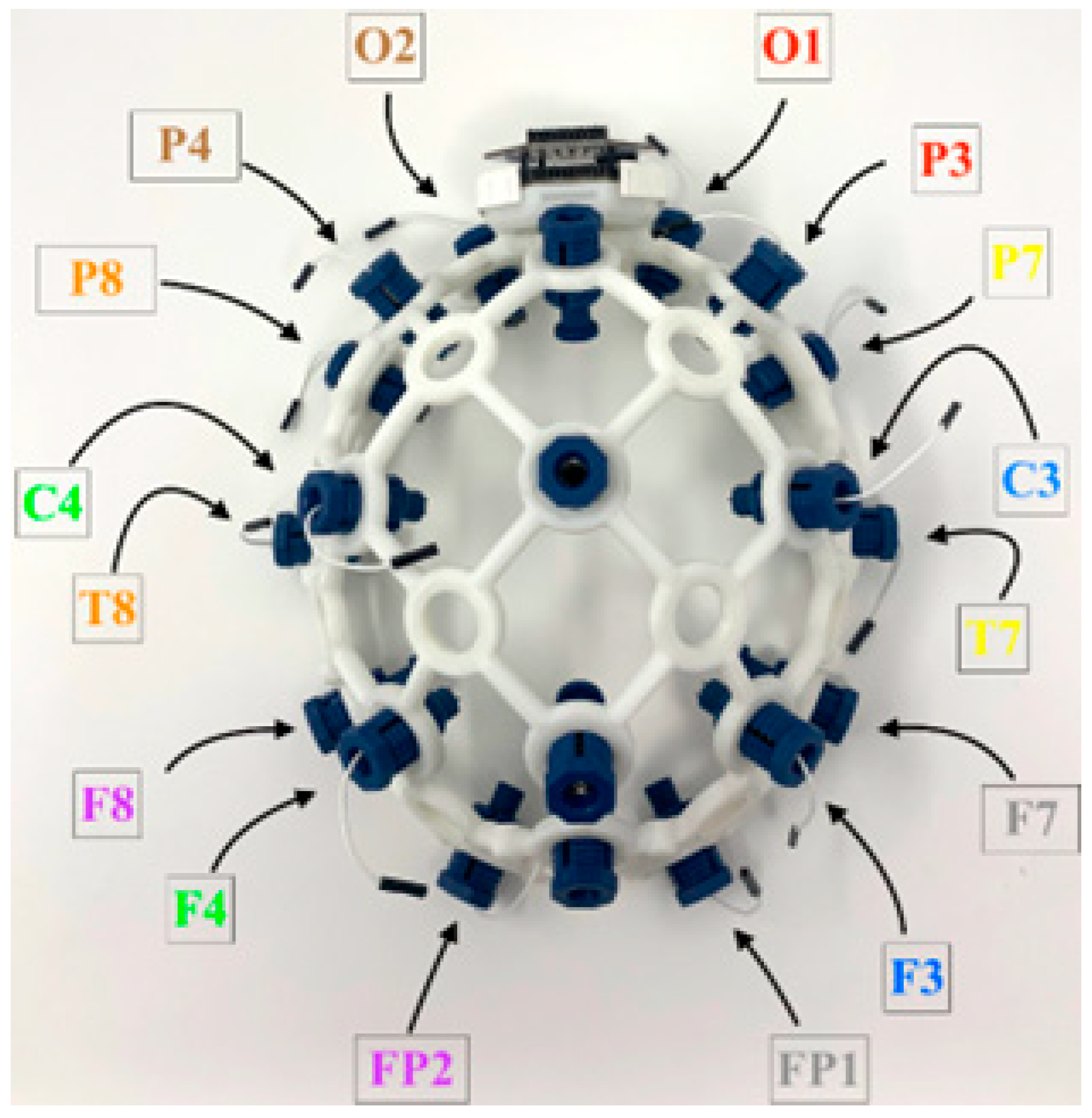

2.5. Design Requirements

EEG data acquisition was implemented using open-source hardware and software, specifically the OpenBCI Cyton biosensing board in conjunction with the Ultracortex Mark IV headset. Sixteen channels of scalp EEG data were recorded at a sampling rate of 250 Hz. Data acquisition and timestamping were automated via a custom Python script to ensure temporal precision and reproducibility. As illustrated in

Figure 4, electrodes were positioned according to the international 10–20 system at the following sites: Fp1, Fp2, F7, F3, F4, F8, T3, C3, C4, T4, T5, T6, P3, P4, O1, and O2.

Each trial was recorded as an individual file, with the filename encoding the image identifier, trial number, and participant ID. Trials lacking valid timestamp data were excluded from further analysis, which amounted to less than 2% of total trials. Inclusion criteria required a minimum of two trials with valid timestamps for each image-participant combination for that participant's data to be retained in the final dataset. Feature extraction and classification processes were executed offline after data collection. Additionally, a real-time pipeline was prototyped that implemented a sliding window of 2 seconds advanced in 200 ms increments.

2.6. Feature Extraction

Selecting feature types was based on prior work, principally the spatiotemporal features and amplitude [

53]. Each file contained approximately 20 seconds of EEG data. Data from each EEG channel were segmented into 1-second non-overlapping windows and processed independently. For each window, time-domain features were extracted. Windows exhibiting total signal amplitudes exceeding ±3 standard deviations from the session baseline were identified as artifacts and excluded from further analysis. Remaining signals were bandpass filtered between 0.1 Hz and 125 Hz using a 4th-order Butterworth filter, with additional notch filtering applied to suppress 60 Hz line noise. A temporal average was then computed for each window, as this feature has demonstrated utility in previous imagined speech BCI studies. Subsequently, the 99.95th percentile of signal amplitude (percent intensity) was calculated for each window. Finally, power spectral density (PSD) features were computed using Welch’s method for major EEG frequency bands: delta (1–4 Hz), theta (5–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and gamma (30–100 Hz), in alignment with standard EEG analysis protocols [

54,

55]. The mean power within the lower and upper sub-bands of each EEG frequency band was computed (e.g., 8–10 Hz for the lower alpha sub-band). Extracted features included both absolute (non-normalized) spectral power values and values normalized with respect to the total spectral power across all frequency bands.

2.7. Data Classification

The classification framework comprised both intrasubject and intersubject analyses. Intrasubject classification evaluated the feasibility of subject-specific EEG-based image identification by assessing the classifier’s performance on data from a single participant. Low classification metrics—such as accuracy, F1 score, or area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC)—were indicative of suboptimal signal quality or insufficient feature separability. In contrast, intersubject classification assessed model generalizability across participants, providing insight into the potential for a subject-agnostic EEG-based image identification system. Successful decoding across subjects suggested that model performance could scale with larger datasets. Feature selection was performed using the Average Distance between Events and Non-Events (ADEN) method, incorporating two statistical weighting schemes to identify the most informative features for each classification scenario [

55].

ADEN is a supervised feature selection technique designed to identify the top three to six discriminative features per run, using only the training dataset. For each class, feature values were averaged, followed by a scaling step that applied a combination of z-score normalization and Cohen’s d effect size. The absolute difference between the scaled class averages was then computed for each feature. Features were ranked by the magnitude of this inter-class distance, with the highest value indicating the greatest separability between classes. The feature selection process ran independently for each participant and each classifier model, so the exact number of unique features varied. For each case, the top-ranked three to six features were selected for downstream application on the validation data [

55].

Given the presence of 16 input channels and the potential for noise in the data, overfitting was identified as a significant concern. To mitigate this, evaluation metrics that are less sensitive to class imbalance and better reflect model generalization—such as the F1 score and AUC-ROC—were prioritized over overall classification accuracy. In light of these concerns, traditional machine learning algorithms were favored over more complex deep learning models to reduce the risk of overfitting. Based on prior methodologies used in comparable BCI systems, three classifiers were implemented for evaluation: Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), Random Forest (RF), and k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) [

56]. For each classification task, the dataset was randomly partitioned into four blocks. Classification was modeled as a one-vs-rest problem for each of the 12 images, with class balance achieved using methods suitable for limited sample sizes. Training and testing splits were designed to maintain equivalent class distributions. Each classifier specific to an image employed four-fold leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV), holding out one block at a time for validation to assess generalization reliability. Classification metrics—accuracy, F1 score, and AUC-ROC—were computed for each configuration and then averaged across both systems and image categories. Experiments were conducted for both intrasubject and intersubject classification scenarios to evaluate model robustness.

2.8. Design Requirements

The “Thunderhead” device designed in this study is a handheld vortex ring generator capable of extinguishing fires at a distance. Conductive vortex rings, with this requisite, were utilized to determine the device’s effective range.

To evaluate the potential performance enhancement offered by an instinctive image identification system in processing electronic commands and messages, the information transfer rate (

ITR) was computed for each system configuration using Equation (Eq.) 1 [

10].

As shown in Eq. 1, is quantified as bits per trial. The effectiveness of a classification system is directly influenced by both the number of distinct classes ( and classification accuracy (.

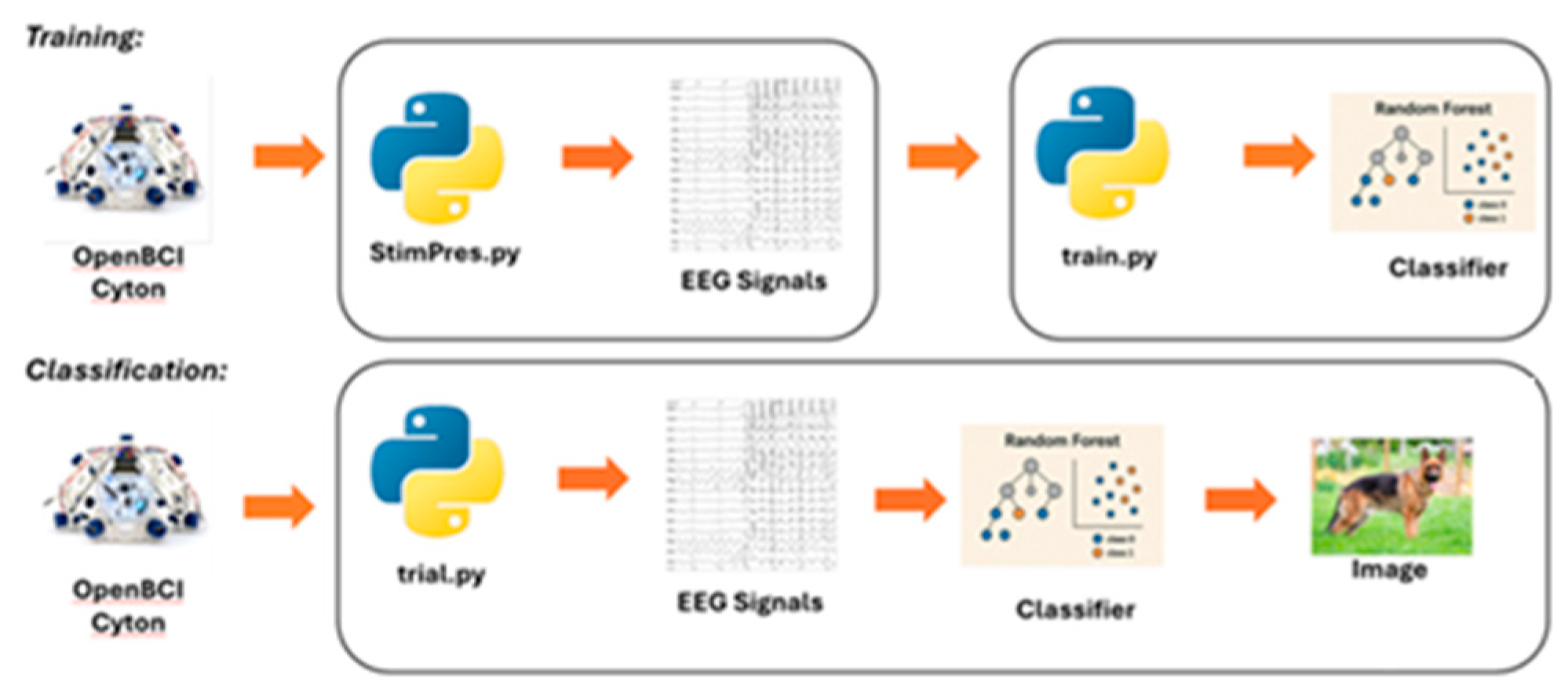

In the implemented system illustrated in

Figure 5, integers from 1 to 12 were assigned for each image. The participant wore the OpenBCI EEG headset, and the presentation displayed each image with the “StimPres” Python script. The participant was instructed to remember the prior image for 10 trials. Each participant had a number of uniquely coded EEG trials, with file names corresponding to image code and trial number. A portion randomized of the EEG files from an individual participant were processed and trained classifiers using the “train” Python script. Testing and validation occurred with the “trial” Python script, which used previously withheld validation EEG files on each classifier model. When the classifier model observed a validation EEG file, it was assigned an integer, from 1 to 12, corresponding to which image the model calculated it belonged to. The classifier output was compared to the “gold standard,” which was used to generate the confusion matrix and performance metrics.

Owing to the structure of the classifier, each image is also evaluated against itself at a temporally distinct point. Consistent and accurate identification of the same object across different timepoints serves as evidence of discrete temporal encoding [

57]. To streamline the computation, a 1-second sampling window was adopted in accordance with the data acquisition protocol. Subsequently, Equation 2 was applied to convert the results to bits per minute.

Classifier performance is a critical factor in achieving a high Information Transfer Rate (ITR). Based on prior benchmarking results, it was anticipated that the Random Forest (RF) classifier would achieve superior average performance across key metrics including accuracy, AUC, and F1 score [

27]. Previous studies also suggest that the most informative features for classification are spectral band power and average mean amplitude, particularly when extracted from electrodes positioned on the upper and posterior regions of the scalp [

49,

53]. Specifically, electrodes located at parietal and occipital sites—such as Pz, P4, and Oz within the 10–20 International System—have been consistently associated with EEG patterns linked to visual recall, likely due to their anatomical proximity to the visual cortex [

6,

49]. Additionally, while gamma-band activity related to visual recall has been observed in frontal electrodes, these signals may be confounded by ocular artifacts [

58]. To validate the feasibility of the proposed approach, initial classification tests were conducted in an offline setting. Statistical testing was performed to determine any significant differences between the classifiers, using paired

t-tests.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

Classifier performance was evaluated for the image identification system across multiple scenarios. The first scenario assessed intrasubject classification, measuring the system’s ability to discriminate images within individual subjects. The second scenario focused on intersubject classification, testing the generalizability of the model when trained on one subject's data and validated on another's. The third analysis involved feature and electrode selection to identify those contributing most significantly to robust image separation. For each phase, the ITR was computed to quantify system effectiveness. Subsequently, 3D object reconstructions were generated using the ComfyUI pipeline.

3.2. Intrasubject Competition

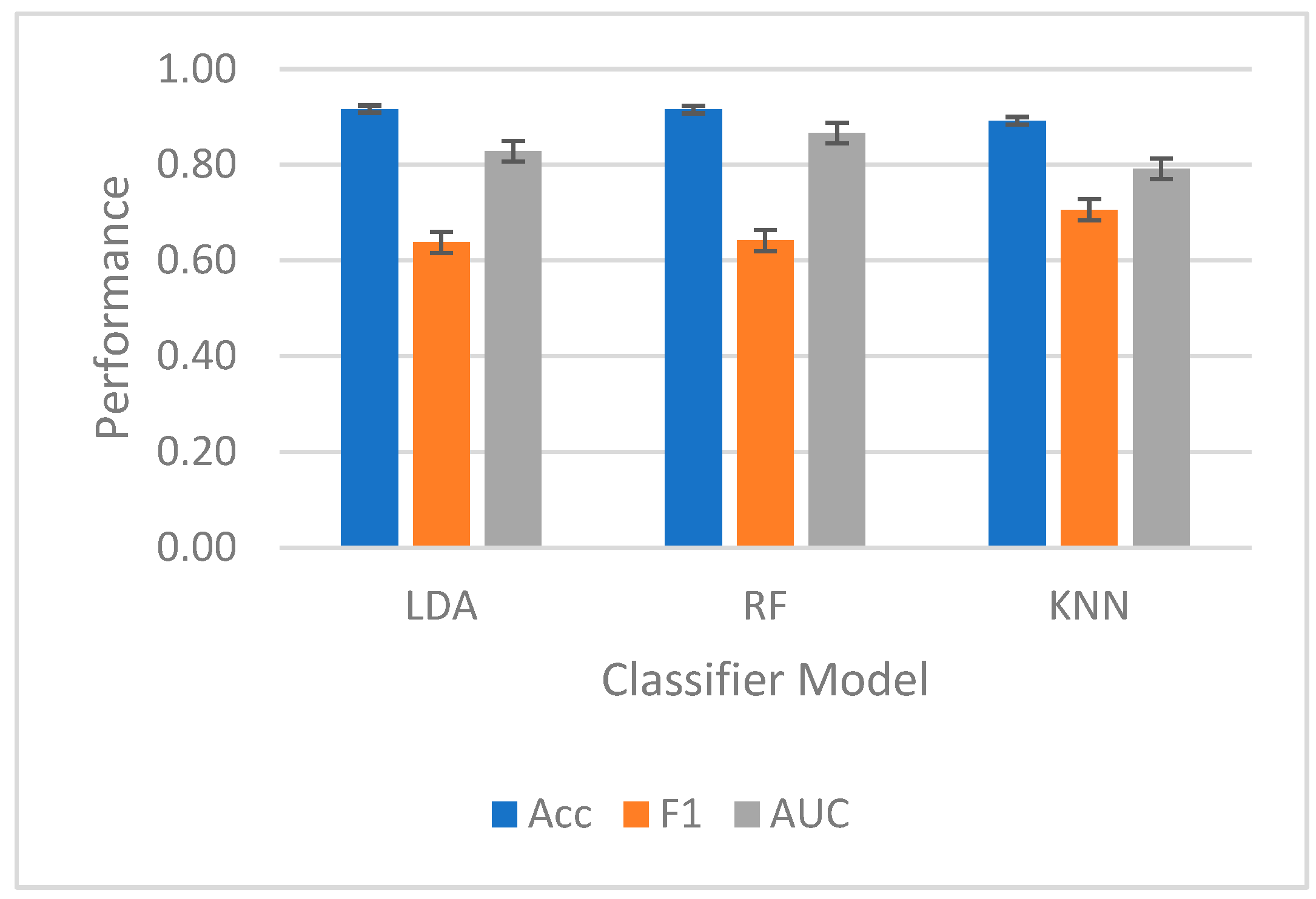

For intrasubject classification shown in

Figure 6, the highest-performing classifier for F1 and AUC-ROC was RF. RF reached a mean accuracy of 92 ± 4%, a mean F1 score of 0.64 ± 0.08, and a mean AUC-ROC of 0.87 ± 0.09. LDA achieved a mean accuracy of 92 ± 4%, a mean F1 score of 0.64 ± 0.05, and a mean AUC-ROC of 0.87 ± 0.11. KNN achieved a mean accuracy of 89 ± 1%, a mean F1 score of 0.71 ± 0.08, and a mean AUC-ROC of 0.87 ± 0.09. No significant differences were found between classifier types.

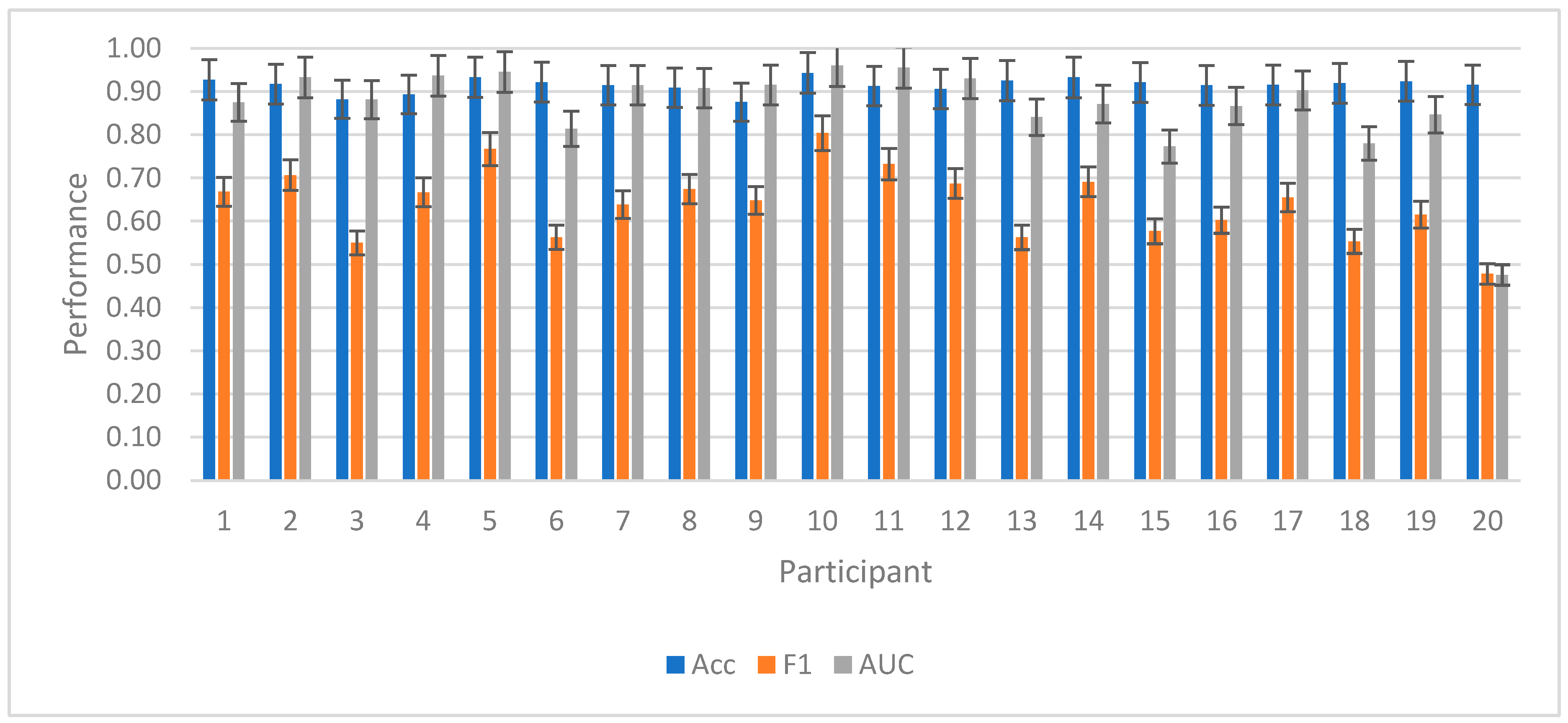

Performance across individual participants was plotted for RF in

Figure 7. The average rate of bits per intrasubject trial was 2.83, leading to an ITR of 170.2 bits per minute.

3.3. Intersubject Competition

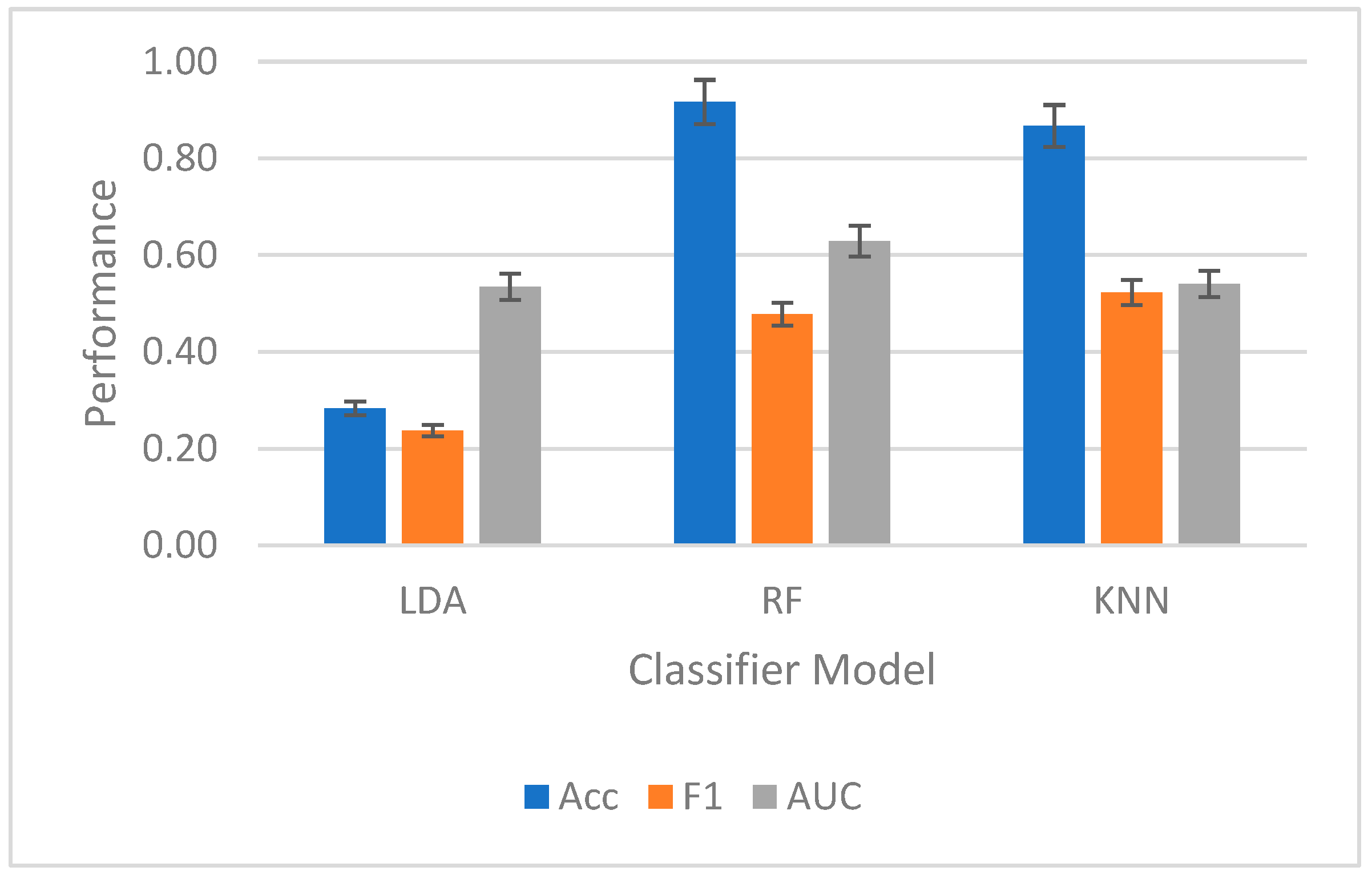

In

Figure 8, the results for intersubject classification were plotted in

Figure 8. Significant differences were found with post-hoc tests (

p value < 0.02), contrasting both LDA against RF and LDA against KNN.

On intersubject classification, the highest average performance was with RF, which resulted in a mean accuracy of 92 ± 0.015%, a mean F1 score of 0.48 ± 0.01, and a mean AUC-ROC of 0.63 ± 0.05. For intersubject classification, the bits per trial for RF was 2.91, and the ITR was 174.4 bits per minute.

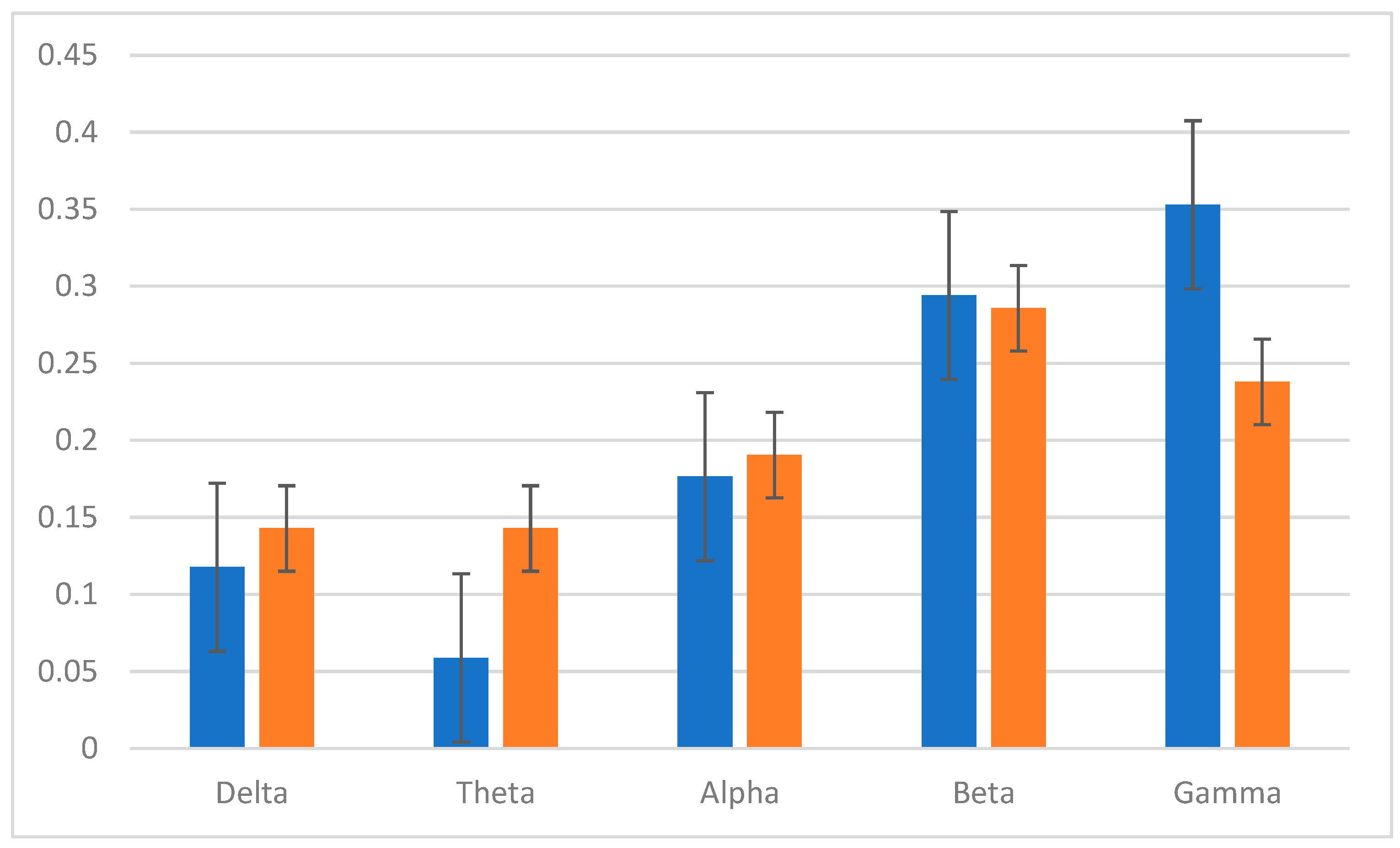

3.4. Top Features

Based on the average maximum distances between images, spectral power on gamma and beta spectral powers were the most consist separable feature across each image and electrode channel. The most consistent electrode positions for the features were frontal, including Fp1, Fp2, F3, and F4.

The normalized EEG bands are shown in

Figure 9, indicating the power on higher frequency bands.

3.5. Image to Object

Each object was converted into a 3D object, as shown in

Figure 10. Other conversions are detailed in the supplemental details.

The files and code are available in the repository, linked in the data availability statement.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview

EEG data from all 20 participants was viable for an image reconstruction system. Compared to the intersubject model, the individualized models worked most reliably with gamma and beta features on frontal electrodes, reaching a mean accuracy mean accuracy of 92 ± 4%, a mean F1 score of 0.64 ± 0.08, and a mean AUC-ROC of 0.87 ± 0.09. Earlier studies in visual recall noted F3 and F4 were active, although Fp1 and Fp2 often had ocular artifact contamination [

58]. Prior work did not directly incorporate temporal encoding of discrete stages, the transformation of objects over time [

42,

43,

44]. Objects can be reliably separated from themselves at different time points reliably, even with a low-cost EEG headset. Incorporating transformation and dynamism into encoding of visual memory directly enables more naturalistic and realistic context of individual objects. The use of low-cost EEG headsets with open-source software could greatly improve the accessibility of the technique and technology, especially in engineering and expression [

4,

26]. From art to the physically impaired, the technology could assist with rapid prototyping of designs [

4,

26]. The use of an older, less complex machine learning technique precludes the need to run a GAN, although higher resolution models would require extensive training and hardware. Starting with a finite number of images, the “one versus rest” classifier framework can be generalized for a higher, dynamic number of categories. While limitations remain, the system reliably differentiates and reconstructs object representations at distinct time points. These foundational results highlight the potential for developing robust, scalable, and interactive EEG-driven image reconstruction systems, paving the way for real-time applications in research, engineering, and creative industries. The conversion of EEG into temporally encoded 3D objects has been demonstrated reliably, although limitations were present.

4.2. Limitations

The current system primarily was validated offline, although the system requires substantial improvement. A primarily limitation was the reliance on offline performance, but it was essential to establish a proof of concept. A second limitation was potential noise from ocular artifacts, although this could be compensated for by using certain frontal channels for artifact rejection and other techniques [

58]. Another limitation was the relatively small size of participants and images, which was due to establishing a precedent that could be built on. A potential limitation was using a modified “one versus rest” classifier ensemble with a fixed number of categories, rather than a dynamic number. While the system could be dynamically updated in future configurations, the number of active categories is likely to be dynamic. Another potential shortcoming was bypassing the use of a GAN in widely existed prior work [

4,

5,

26]. Similarly, the quality of 3D objects could be improved, which could require a specialized model [

26]. However, future work could simply scale existing precedents established in this study and elsewhere. These limitations detail clear precedents for improvement.

4.3. Future Work

The clear next step is optimization of the real-time system. The prototypical “one versus rest” classifier could be adapted for a dynamic number of categories. A pre-trained GAN could be included, in order to refine the resolution of 3D objects. The separability of objects in a scene could also be improved to ensure greater reliability [

4,

5,

26]. Methods incorporating human-computer interaction, and ability to customize objects or edit generated videos intuitively, further bridging the gap between imagination and engineering. Advances in other generative AI fields could also be applied, such as extrapolating or interpolation the state of an object more efficiently [

40,

56]. The system could also be adapted for specific uses, such as manufacturing (using different versions of a product), animation (streamlining animation for 2D images), or transportation (recalling landmarks along a route) [

25]. Real-time streaming of memories, imagined images, and dynamic scenes has already been established, but reducing hardware requirements directly improves its accessibility [

4,

5,

14,

26].

5. Conclusions

This study establishes the technical feasibility of reconstructing dynamic visual imagery from EEG data using individualized models, even when constrained to low-cost consumer-grade headsets and open-source software environments. The proposed system demonstrates robust classification and reconstruction performance, achieving high accuracy, F1 score, and AUC-ROC, with optimal results observed when gamma and beta band features are extracted from frontal electrodes-regions known to be associated with cognitive control and visual processing [

58]. By integrating temporal encoding mechanisms, the approach captures object transformations across time, yielding a more ecologically valid representation of visual memory compared to static or single-frame reconstruction paradigms [

4,

5,

14,

26]. Despite inherent limitations, including offline validation, a modest sample size, and the use of relatively simple machine learning algorithms, the system reliably differentiates and reconstructs object representations at distinct temporal intervals. While there remain significant opportunities for improvement-such as real-time operation, artifact mitigation, the foundational results presented here underscore the potential for developing more robust, scalable, and interactive EEG-driven image reconstruction systems, paving the way for practical deployment in research, art, and industrial contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and Z.S.; methodology, Z.S. and Y.L.; software, Z.S.; validation, J.L., E.H., and Q.T.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, J.F., Y.L., and E.H.; resources, Z.S.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L.; visualization, J.S.; supervision, J.L. and Q.T.; project administration, J.L., J.F., and S.M.; funding acquisition, Q.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank The Ohio State University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acar, Z.A.; Acar, C.E.; Makeig, S. Simultaneous head tissue conductivity and EEG source location estimation. NeuroImage 2016, 124, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, M.; Luo, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, L. Beats: an open-source; high-precision, multi-channel EEG acquisition tool system. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2022, 16, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technologies, T.C.; Positioning, S. , 2012. [Online]. Available: https://trans-cranial.com/docs/10_20_pos_man_v1_0_pdf.pdf. [Accessed 21 Feb 2023].

- Song, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Shi, N.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X. Decoding natural images from eeg for object recognition. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.13234. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Liu, J. A New Framework Combining Diffusion Models and the Convolution Classifier for Generating Images from EEG Signals. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ren, K.; Shi, H.; Wang, Z.L.D.; Lu, B.; Zheng, W. EEG2video: Towards decoding dynamic visual perception from EEG signals. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 72245–72273. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, N.; Meshi, D.; Bente, G.; Schmälzle, R. Media neuroscience on a shoestring. J. Media Psychol. Theor. Methods Appl. 2023, 35, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capati, F.A.; Bechelli, R.P.; Castro, C.F. Hybrid SSVEP/P300 BCI keyboard. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies, Rome, Italy; 2016; Volume 2016, pp. 214–218. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, B.; Luth, T.; Valbuena, D.; Teymourian, A.; Volosyak, I.; Graser, A. BCI Demographics: How Many (and What Kinds of) People Can Use an SSVEP BCI? IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabilitation Eng. 2010, 18, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blankertz, B.; Dornhege, G.; Krauledat, M.; Muller, K.-R.; Kunzmann, V.; Losch, F.; Curio, G. The Berlin brain-computer interface: EEG-based communication without subject training. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabilitation Eng. 2006, 14, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kübler, A. The history of BCI: From a vision for the future to real support for personhood in people with locked-in syndrome. Neuroethics 2019, 13, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Pandey, P.; Miyapuram, K.; Raman, S. EEG2IMAGE: image reconstruction from EEG brain signals. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, 2023; volume 2023, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, H.; Srinivasan, R.; Zhang, Q. Improving classification and reconstruction of imagined images from EEG signals. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0274847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRocco, J.; Tahmina, Q.; Lecian, S.; Moore, J.; Helbig, C.; Gupta, S. Evaluation of an English language phoneme-based imagined speech brain computer interface with low-cost electroencephalography. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1306277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; LeBel, A.; Jain, S.; Huth, A.G. Semantic reconstruction of continuous language from non-invasive brain recordings. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Bernal, D.; Balderas, D.; Ponce, P.; Molina, A. A State-of-the-Art Review of EEG-Based Imagined Speech Decoding. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 867281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Reconstructing Static Memories from the Brain with EEG Feature Extraction and Generative Adversarial Networks. J. Stud. Res. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Ping, Y.; Guo, X.; Cui, Z. A BCI painting system using a hybrid control approach based on SSVEP and P300. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 150, 106118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Xia, N.; Tao, M.; Pan, D.; Zheng, H.; Wang, C.; Xu, F.; Zakaria, W.; Dai, G. DCAE: A dual conditional autoencoder framework for the reconstruction from EEG into image. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2022, 81, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa, K.; Nagano, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Aoki, S.C.; Muraki, Y.; Majima, K.; Kamitani, Y. Spurious reconstruction from brain activity. Neural Networks 2025, 190, 107515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Sharma, K.; Jha, R.R.; Bhavsar, A. NeuroGAN: image reconstruction from EEG signals via an attention-based GAN. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 35, 9181–9192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kalliny, M.M.; Jr, J.H.W.; Sheehan, T.C.; Sreekumar, V.; Inati, S.K.; Zaghloul, K.A. Changing temporal context in human temporal lobe promotes memory of distinct episodes. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde-Domingo, J.; Treder, M.S.; Kerrén, C.; Wimber, M. Evidence that neural information flow is reversed between object perception and object reconstruction from memory. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Pazdera, J.K.; Kahana, M.J. EEG decoders track memory dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Jia, J.; Han, Q.; Luo, H. Fast-backward replay of sequentially memorized items in humans. eLife 2018, 7, e35164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakita, S.; Orima, T.; Motoyoshi, I. Photorealistic Reconstruction of Visual Texture From EEG Signals. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 754587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.; Lee, A.; Armstrong, B.; Nestor, A. How are visual words represented? insights from EEG-based visual word decoding, feature derivation and image reconstruction. Human Brain Mapping 2019, 40, 5056–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestor, A.; Plaut, D.C.; Behrmann, M. Feature-based face representations and image reconstruction from behavioral and neural data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 113, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuad, N.; Taib, M.N. Three Dimensional EEG Model and Analysis of Correlation between Sub Band for Right and Left Frontal Brainwave for Brain Balancing Application. J. Mach. Mach. Commun. 2015, 1, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghi, N.; Rezaii, T.Y.; Beheshti, S.; Meshgini, S.; Sheykhivand, S.; Danishvar, S. Visual Saliency and Image Reconstruction from EEG Signals via an Effective Geometric Deep Network-Based Generative Adversarial Network. Electronics 2022, 11, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wen, H.; Wang, S.; Clark, R.; Markham, A.; Trigoni, N. 3D object reconstruction from a single depth view with adversarial learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision workshops; 2017; vol. 2017, pp. 679–688. [Google Scholar]

- Nemrodov, D.; Niemeier, M.; Patel, A.; Nestor, A. The Neural Dynamics of Facial Identity Processing: Insights from EEG-Based Pattern Analysis and Image Reconstruction. eneuro 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, Y.-C.; Wang, Y.-K.; Prasad, M.; Lin, C.-T. Brain dynamic states analysis based on 3D convolutional neural network. Trans. IEEE Int. Conf. Syst. Man Cybern. 2017, 2017, 222–227. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Kim, D.-W.; Han, C.-H.; Im, C.-H. Estimation of Emotional Arousal Changes of a Group of Individuals During Movie Screening Using Steady-State Visual-Evoked Potential. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 731236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashkov, G.; Bobe, A.; Fastovets, D.; Komarova, M. Natural image reconstruction from brain waves: a novel visual BCI system with native feedback. BioRxiv 2019, 2019, 787101. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Peng, D.; Chen, L.; Wu, C.; Wei, Z.; Childs, P.; Guo, Y.; Li, L. Neurocognition-inspired design with machine learning. Des. Sci. 2020, 6, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Horikawa, T.; Majima, K.; Kamitani, Y.; O'REilly, J. Deep image reconstruction from human brain activity. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1006633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taberna, G.A.; Marino, M.; Ganzetti, M.; Mantini, D. Spatial localization of EEG electrodes using 3D scanning. J. Neural Eng. 2019, 16, 026020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clausner, T.; Dalal, S.S.; Crespo-García, M. Photogrammetry-Based Head Digitization for Rapid and Accurate Localization of EEG Electrodes and MEG Fiducial Markers Using a Single Digital SLR Camera. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y.; Kong, K.; Song, W.-J.; Min, B.-K.; Kim, S.-E. Multilevel Feature Fusion With 3D Convolutional Neural Network for EEG-Based Workload Estimation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 16009–16021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesi, M.; Guermandi, M.; Placati, S.; Scarselli, E.; Guerrieri, R. Creamino: A cost-effective, open-source EEG-based BCI system. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 66, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostenveld, R.; Fries, P.; Maris, E.; Schoffelen, J. Fieldtrip: open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2011, 2011, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil Ávila, C.; Bott, F.S.; Tiemann, L.; Hohn, V.D.; May, E.S.; Nickel, M.M.; Zebhauser, P.T.; Gross, J.; Ploner, M. DISCOVER-EEG: an open, fully automated EEG pipeline for biomarker discovery in clinical neuroscience. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardona-Álvarez, Y.N.; Álvarez-Meza, A.M.; Cárdenas-Peña, D.A.; Castaño-Duque, G.A.; Castellanos-Dominguez, G. A Novel OpenBCI Framework for EEG-Based Neurophysiological Experiments. Sensors 2023, 23, 3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifanov-Carr, J.; Griffiths, B.J.; Linde-Domingo, J.; Ferreira, C.S.; Wilson, M.; Mayhew, S.D.; Charest, I.; Wimber, M. Reconstructing Spatiotemporal Trajectories of Visual Object Memories in the Human Brain. eneuro 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, M.; Schreiner, T.; Seifritz, E.; Rasch, B. Emotional arousal modulates oscillatory correlates of targeted memory reactivation during NREW, but not REM sleep. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, T.; Xu, S.; Zou, L. Source localization and functional network analysis in emotion cognitive reappraisal with EEG-fMRI integration. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 960784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Ribeiro, B.; Pinto, A.M.; Cardoso, A. Emulating Cued Recall of Abstract Concepts via Regulated Activation Networks. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, S.; Kosmyna, N.; Maes, P. Image classification and reconstruction from low-density EEG. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amemaet, F.; Courses, P. 2021. [Online]. Available: https://pythonbasics.org/text-to-speech/. [accessed 28 January 2022].

- Barratt, S.; Sharma, R. A note on the inception score. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.01973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Lu, Z.; Huang, D.; Ouyang, W.; Bai, L. GenAgent: Build Collaborative AI Systems with Automated Workflow Generation--Case Studies on ComfyUI. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.01392. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-García, A.A.; Reyes-García, C.A.; Villaseñor-Pineda, L.; García-Aguilar, G. Implementing a fuzzy inference system in a multi-objective EEG channel selection model for imagined speech classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 59, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRocco, J.; Le, M.D.; Paeng, D.-G. A Systemic Review of Available Low-Cost EEG Headsets Used for Drowsiness Detection. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 553352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRocco, J.; Innes, C.R.H.; Bones, P.J.; Weddell, S.; Jones, R.D. Optimal EEG feature selection from average distance between events and non-events. In Proceedings of the 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2014; pp. 2641–2644. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, U.; Alzubaidi, M.; Mohsen, F.; Abd-Alrazaq, A.; Alam, T.; Househ, M. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Decoding Speech from EEG Signals: A Scoping Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRocco, J.; Paeng, D.-G. Optimizing Computer–Brain Interface Parameters for Non-invasive Brain-to-Brain Interface. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assem, M.; Hart, M.G.; Coelho, P.; Romero-Garcia, R.; McDonald, A.; Woodberry, E.; Morris, R.C.; Price, S.J.; Suckling, J.; Santarius, T.; et al. High gamma activity distinguishes frontal cognitive control regions from adjacent cortical networks. Cortex 2022, 159, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).