1. Introduction

Efficient material handling is a key element in mining operations since its direct influence on productivity, safety and operating costs. As the mining industry moves towards deeper ore bodies extraction [

1], there is a demand to develop reliable and cost-effective technologies such as long-distance transportation systems [

2,

3]. One of the representative examples of the long-conveyor system is the Sasol’s Impumelelo coal conveyor in South Africa. The 27 km long conveyor’s route is barely inclined - around 50 m of the elevation between the tail and head pulleys length. The conveyor is designed to transport up to 2 400 t/h at maximum belt speed 6.5 m/s. A specially selected ST 2000 belt with super low rolling resistance belt bottom cover was chosen to improve the energy efficiency. The relatively low operational belt tension was achieved with the unique drive layout - the conveyor is powered by 6 motors (4 x 1 000 kW and 2 x 500 kW) located in three positions: at the head, tail and booster station (intermediate drive station) and it is additionally equipped with mid-flight fixed tripper station [

4]. Another noteworthy example is the Chuquicamata Underground Mine Project in Chile. The underground conveyor system overcomes 1 km of the elevation difference along the 7 km route with the belt speed of 7m/s. Despite the high capacity (11 000 t/h) the system consists of only 2 conveyors with the 8 x 5 000 kW of installed total drive power. It should be noted that the top-end tensile strength ST 10 000 belt was specially developed and installed, and the applied safety factor was decreased by 20% to 5.0 assuming the demanded fatigue strength of splice connection of 50% of the belt tensile strength was retained [

5].

It was recognized that the long-distance conveyor systems are one of the most efficient methods for bulk material transportation over the great distances in the industrial sites [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Belt conveying enables to transport material along the curves, uphill or downhill, achieving high throughput capacity (up to tens thousand tonnes of material per hour) [

10,

11]. Advanced monitoring, remote diagnosis and automated operation enhance reliability of the system, its operational safety and maintenance in difficult mining conditions [

12,

13]. Additionally, long-distance belt conveyors are considered as environmentally friendly due to their low energy consumption, reduced noise and decreased emissions compared to truck-based transport [

14,

15,

16]. It is important to point out that the term long-distance conveyor’ lacks a strict definition in technical literature. In general, it is a material transport system characterized by an exceptionally long route that exceeds the capabilities of standard conveyor solutions. It needs a unique engineering approach, such as multiple drive stations and custom-designed components, with the special focus on especially designed conveyor belt [

10,

11,

17,

18].

The following diagram summarizes the most important aspects for an efficient, reliable and cost-effective conveyor (

Figure 1).

Each of the presented components contributes to the overall performance and sustainability of the conveyor system. Firstly, careful design and selection of main components mainly focuses on drive system configuration, power management and ensuring smooth operation over a long distance. The right belt material and strength selection are important for the belt tension (belt forces) and belt lifespan, while the proper idler design and spacing may significantly influence the rolling and indentation resistance [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Secondly, operational aspects relate to the variability of the mass and load distribution, that is crucial for conveyor dynamic states modelling, belt wear or energy efficiency [

24,

25]. Belt speed adjustment is essential for transportation stability and thus more sustainable conveyor operation [

26,

27,

28]. At the same time, well-designed transfer points [

29,

30] or intermediate drive implementation [

31,

32,

33] help to maintain consistent operation, avoid material spillage and reduce belt tension. Thirdly, optimizing costs and efficiency of conveyor transportation concerns its economic, energy and environmental performance. Both initial investment and long-term maintenance costs must be considered for economic viability. Component selection and system design minimizes energy consumption, reducing operational expenses. In addition, conveyors are more environmentally friendly as they emit less dust and noise and have a lower energy footprint during transportation process when compared to road or rail transport [

34,

35,

36,

37].

Finally, the implementation of robust reliability and safety systems is aimed at monitoring conveyor operation with a view to detecting abnormal operating conditions [

38]. From maintenance point of view the integrated technologies such as vibration, magnetic, temperature or vision components [

39,

40,

41] are crucial for non-destructive diagnosis of belt conveyor condition. Another important element is the intelligent detection of belt misalignment [

42,

43] as it detects, corrects and prevents improper belt handling. Above that, the issue of belt forces is a fundamental matter concerning the transfer of loads and stresses in the belt during conveyor operation [

44,

45]. It was recognized that the aspects crucial for controlling belt forces are as follows:

proper management of load distribution – uneven load distribution leads to vibration, dynamic stresses in the belt and increased variations in belt tension. This can result in excessive energy consumption, belt wear damage or misalignment of the belt [

46,

47,

48].

soft start/stop systems smooth acceleration and stopping, reduce peaks in power transmission and sharp tension fluctuations as well as minimize vibrations. This ensures stable operation, protects the system from potential damage and saves energy [

18,

49,

50].

intermediate drive system distributes drive forces along the conveyor reducing the maximum belt tension and increasing transmitted friction force. This can improve operational reliability and reduce maintenance costs by minimizing the wear and tear on the belt and other component [

18,

31,

32,

33,

46].

implementation of effective tensioning device detects and adjusts belt tension in real-time under varying loads and speeds to prevent the belt from slippage. It helps to avoid excessive strain that leads to prolonging belt lifespan [

51,

52].

proper belt selection – belt parameters e.g. tensile strength or elasticity modulus directly influences the belt tension and prevent from its permanent deformation. An equally important aspect is the belt construction (e.g. steel-cord or fabric), belt condition (e.g. wear level or renovation), the quality of belt splices and belt transition sections behavior [

23,

53,

54,

55].

This paper presents an analysis of the energy efficiency of long-distance inclined belt conveyors designed for an underground copper ore mine. Five alternative solutions were proposed and evaluated. The study includes an analysis of the main resistance components affecting conveyor performance, as well as the detailed impact of conveyor throughput on specific energy consumption. Furthermore, the total electrical energy consumed by each conveyor variant was calculated based on the assumed distribution of material load along the operational range. The aim of the article is to provide an engineering insight into the energy use of one of the key stages of the mining process – material transport. It highlights the importance of selecting belt conveyor equipment for ensuring the efficiency of the mining process.

2. Materials and Methods

The development of the new mining fields, located deeper and farther from the existing main haulage routes, are the typical situations of the underground ore mines. Then there is a need to arrange an efficient transport of the mined ore to shafts with regard to all aspects, described in the

Figure 1. General design assumptions of the study project long-distance, underground belt conveying are summarized here:

The analysed conveying route is straight, 3 km long, it consists of 2 segments: the first 2.7 km inclined at the angle 2°, the second (0.3 km long) is steeper (angle 7°), the average angle 2.5°.

It is assumed that the conveyor line is supplied by the retention bunker to manage material flow, stabilize material stream along the route and provide temporary storage when the conveyor is not in operation.

Designed system capacity is set to 2000 t/h (maximum) and 1000 t/h (average).

Transported material is pre-crushed copper ore without large lumps (density 2.275 kg/m3).

The conveyor is supposed to work as the main transport line favorable operational conditions and minimal belt misalignment are assumed. A safety margin of over 30% of the maximum belt filling cross-section has been assumed to accommodate short-term throughput surges and prevent potential belt-tracking issues along the long-distance route.

The steel-cord belt from a standard series (St 2000, St 2500, St 3150) is analyzed or optionally a dedicated higher-strength version of the belt may be used.

Due to the length of the conveying route, two general solutions are analyzed: single long-distance conveyors (3 km long) and two standard conveyors (1.5 km each). The belt safety factor for the long 3 km single flights is reduced from the standard 6.7 to 5.0 (based on the assumed implementation of belt splices inspection procedures and regular audits of the entire belt loop condition combined with the reduced number of belt lap cycles). For the last reason, the standard belt safety factor was retained for the shorter 1,5 km [

56,

57,

58].

The technical parameters of these conveyors are based on the successfully used in the KGHM underground copper ore mines in Poland domestic Legmet heavy-duty conveyors series of standardized designs [

59]:

belt width of 1.2 m and a belt speed of 3.0 m/s,

standard spacing for the upper idlers is 0.83 m, and for the bottom idlers, 2.5 m, with the upper fixed (non garland) idler sets forming a 30° trough angle and V-type bottom idlers

rollers with an increased diameter of 159 mm (compared to the standard 133 mm).

drive units range from 250 to 500 kW and implementation of variable frequency drives,

belt tensioning: gravity take-up systems.

Calculations of belt conveyors drive power demand were carried out in the QNK-TT domestic software that uses primary resistances to motion rather than the standard simplified friction coefficient method [

60,

61]. The components of the main resistance to motion are calculated precisely by analyzing energy dissipation in belt and transported material as well as interaction between belt and idlers. The software uses object-oriented modeling techniques, including a wide variety of conveyor equipment configurations and operating conditions. These calculations are based on scientifically validated formulas supported by extensive laboratory tests and industrial measurements [

62,

63,

64,

65].

The appropriate measure of efficiency of proposed belt conveyors variants is specific energy consumption indicator – SEC [

66,

67]. It describes the amount of energy needed to transport a mass unit of material over a distance of a length unit (here: W/(kg·m)). However, as pointed out in [

35], for more complex conveying routes, e.g. inclined routes, the route specific energy consumption (SEC)—defined as the amount of energy required to transport a unit mass of material from point A to point B along the route—should be used for comparison (here: W/kg). This value depends on the actual inclination of the route, operational capacity, and the parameters of the given transportation configuration. Equations describing SEC indicators are shown below.

NE - the electric net power of the drive delivered to the conveyor, W;

Qm - actual mass capacity, kg/s;

L- length of the conveyor route, m.

3. Results

This section presents results of calculations performed for different belt conveyors construction variants in the real working conditions (

Table 1). All five options are designed for an uphill conveyor route with a total length of 3,000 m and a vertical lift of 131 m (for Variants 1–4), or two shorter conveyors of 1,500 m and 53 m and 78 m elevation (inclination 2

o and 3

o respectively - Variant 5). Results show that not all variants are capable of achieving the target maximum throughput of 2,000 t/h.

Variant 1 represents the solution with a standard head drive system (4 × 500 kW) and a high-tensile strength St4000 belt, resulting in the highest belt force of 680 kN (88% of the maximum belt strength). For variants 2 and 3 the standard steel-cord belt rated 3150 kN/m (variant 2) and 2000 kN/m (variant 3) are proposed. The lower tensile strength of these belts limit the available maximum capacity to 1600 and 1000 tonnes per hour (respectively), which proves that the standard solution does not match the assumed requirements. Variant 4 introduces an additional intermediate drive (2 × 355 kW) in the top belt strand, effectively reducing belt force to 504 kN (83% of the maximum belt strength) while maintaining comparable power demand. Variant 5 replaces the single long conveyor with two shorter ones, which slightly lowers the total power demand (1 809 kW in total); however, the maximum belt force in the second conveyor reaches 99% of the installed belt's strength.

Both of the proposed long-distance variants that match the capacity requirements, include non-standard solutions: one involves a conveyor belt with increased tensile strength (Variant 1), and the other features a conveyor with an intermediate drive system (Variant 4). The higher (non standard) belt strength causes a need to apply a special layout of belt splices, which can only be made by highly qualified personnel. The intermediate drive system creates additional difficulties with the adjustment of belt tensioning that have to be addressed with the dedicated drive and take-up procedures control system. It has to be provided by the experienced supplier together with the specialized training of the mine staff responsible on maintenance of belt conveyors. One of the main challenges in implementing innovative solutions in mining operations is organizational resistance to change. Users of machinery systems often prefer standard machinery components because they are readily available in stock, well-known to the staff, and easier to assess in terms of quality and reliability. Introducing non-standard solutions - whether in the form of unconventional components or a novel system layout - can raise operational concerns [

68,

69]. For example, servicing conveyor belts with different tensile strength may lead to maintenance difficulties and requires alternative operating instructions, increasing the risk of errors. This preference for familiar, proven equipment comes not only from logistical convenience but also from a tendency to avoid the complexities and uncertainties associated with managing and maintaining non-standard configurations.

Conveyor resistance to motion as well as lifting transported bulk material directly influence its energy consumption. Therefore, the components of main resistance to moitin of the proposed conveyors have been analyzed.

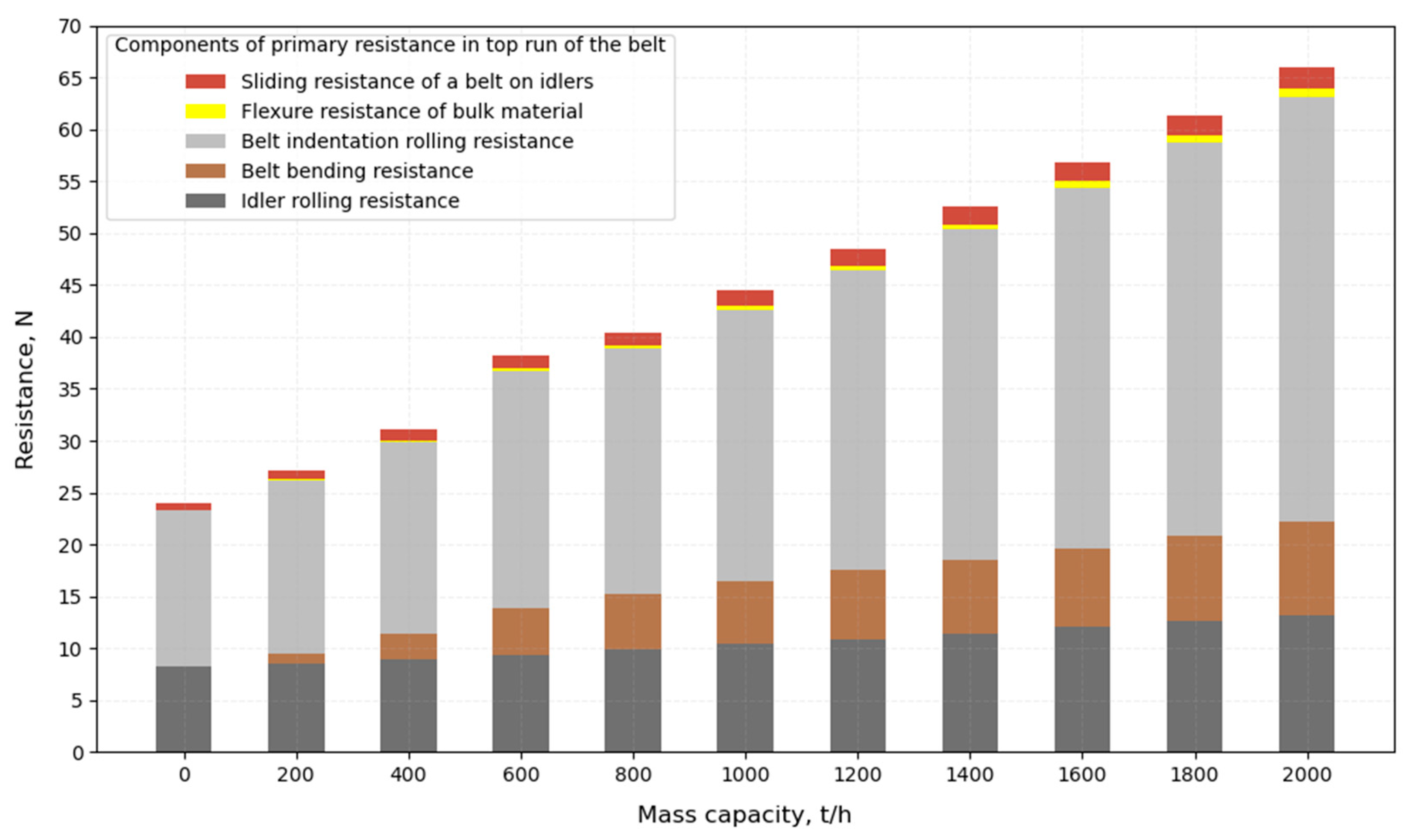

Figure 2 presents the components of primary resistances to motion in the top belt strand as a function of mass flow rate for conveyors named Variant 1. Five resistance components are calculated:

idler rolling resistance,

belt bending resistance,

belt indentation rolling resistance,

flexure resistance of bulk material,

sliding resistance of a belt on idlers.

In general, as the throughput increases the total resistance increases as well. For every component there is a relationship between its value and mass flow rate, although it is not strictly linear. The most significant contribution comes from belt indentation rolling resistance and idler rolling resistance [

14,

20,

56,

60,

65,

67]. This indicates potential for improvement in belt and idler selection – reducing their resistance will lower total conveyor resistance, required power and ultimately belt conveyor energy consumption.

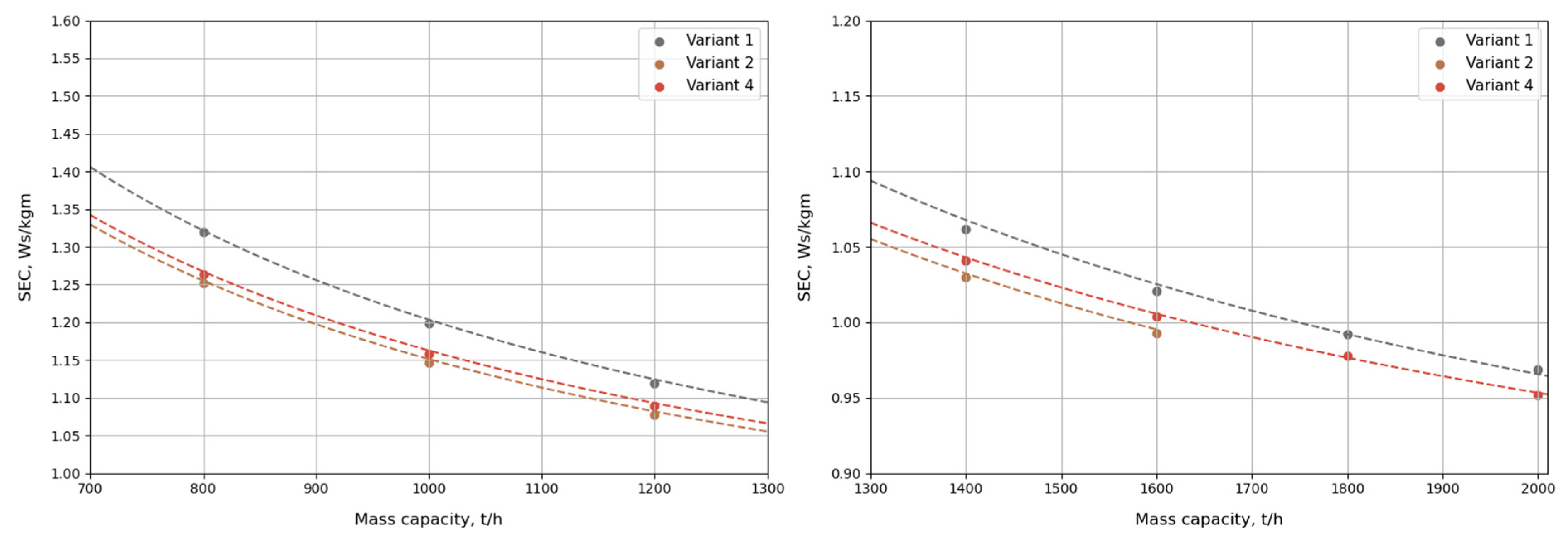

For the proposed design variants, the SEC index was calculated.

Table 2 presents the SEC values both unit indicator and route indicator for two operating conditions: average and maximum capacity. This shows how each variant behaves under typical and peak loading scenarios, helping to assess how effectively each system utilizes energy over its transport route. All variants represent similar energy efficiency, due to the fact that they have been composed with the use of the same conveyor components except the differentiated belt strength (and – consequently – unitary mass of the belt) and drive layout. The standard strength steel-cord belt used for variants 2, 3 and 5 returns slightly lower SEC values in analyzed capacity scenarios (though the maximum capacity si not available for variants 2 and 3). Variant 4, which introduces an innovative intermediate drive, achieves an improvement in efficiency compared to Variant 1 - particularly at maximum capacity - demonstrating the benefits of redistributed drive power. Variant 1, using a high-strength belt for a single conveyor, shows higher SEC values but (together with the variant 4) represents the highest margin of the maximum belt force (

Table 1).

Because the differences in SEC values among these variants are not prevailing, it is important to consider investment and operational costs generated by each of the proposed solutions. In particular, the variant with two conveyors (Variant 5) will result in doubled investment costs of the main components such as drive units, brakes, and take-up devices must be installed for each conveyor separately. Moreover, any transfer point of conveyed bulk material requires a surveillance either directly by a dedicated staff or with the use of cameras and additional gauges to prevent possible operational failures.

Figure 3 presents a comparison of specific energy consumption (SEC) as a function of mass capacity (in t/h) for three system configurations labeled as Variant 1, Variant 2, and Variant 4, because they represent the same route layout. Each variant is represented with calculated data points and a corresponding fitted curve based on a hyperbolic model. All variants show a decreasing trend in SEC as mass capacity increases. Variant 4 demonstrates the best performance in terms of efficiency, followed by Variant 2 and Variant 1. Given that the differences in SEC values between the variants are relatively small, the relationship is presented with two different mass capacity ranges. Moreover, since the considered system represents main haulage conveyor, which should not operate at low capacities, it was arbitrarily assumed that the analyzed capacity range would start from 700 t/h.

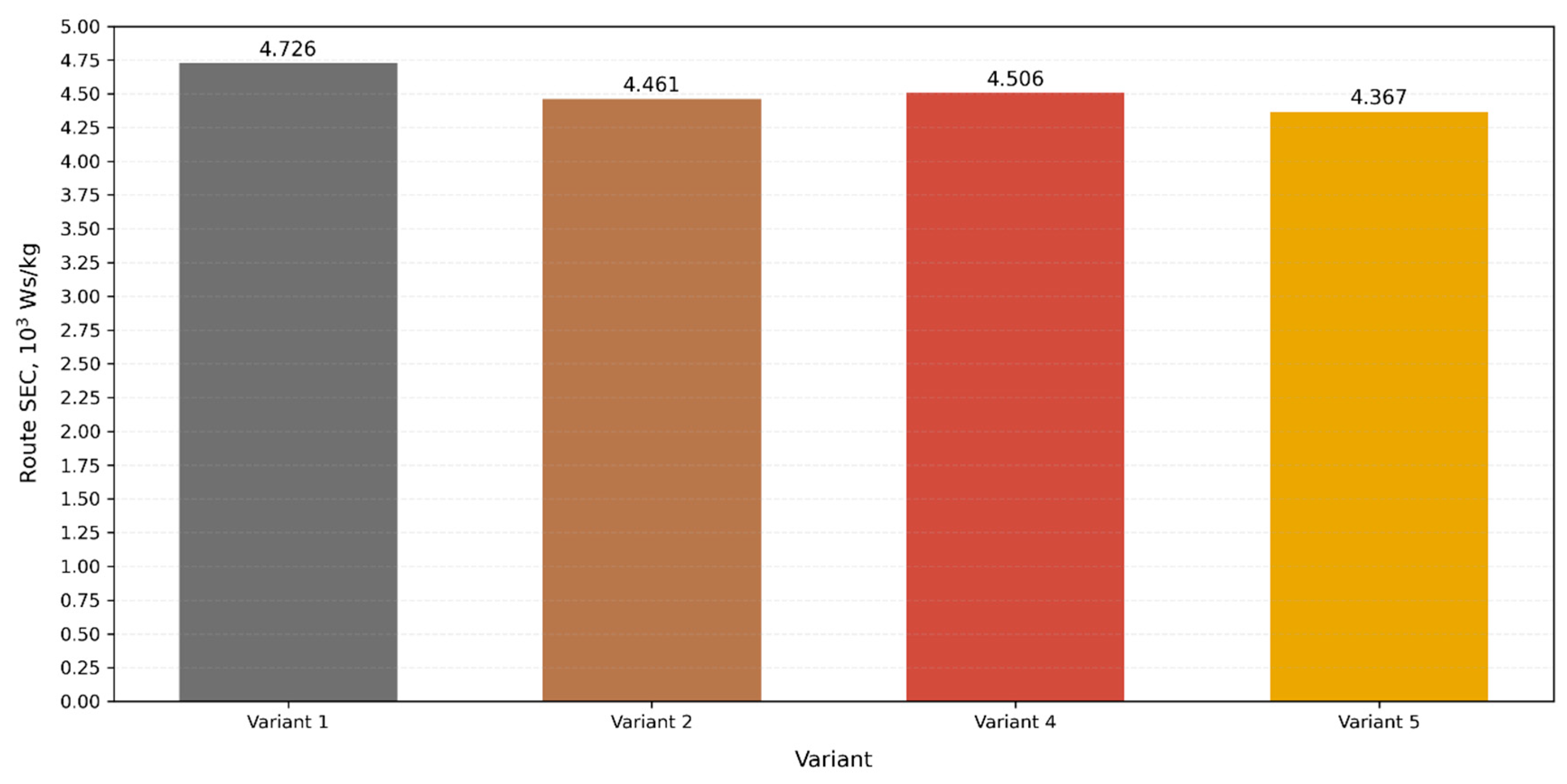

In the next step the route SEC for analyzed variants was calculated assuming on the basis of the measured distribution of mass capacity of conveyors used in KGHM PM S.A. underground copper mine for a main haulage conveyor [

62] (

Table 3). The results of the expected mean value of the energy consumed by the conveyors are presented in

Figure 4.

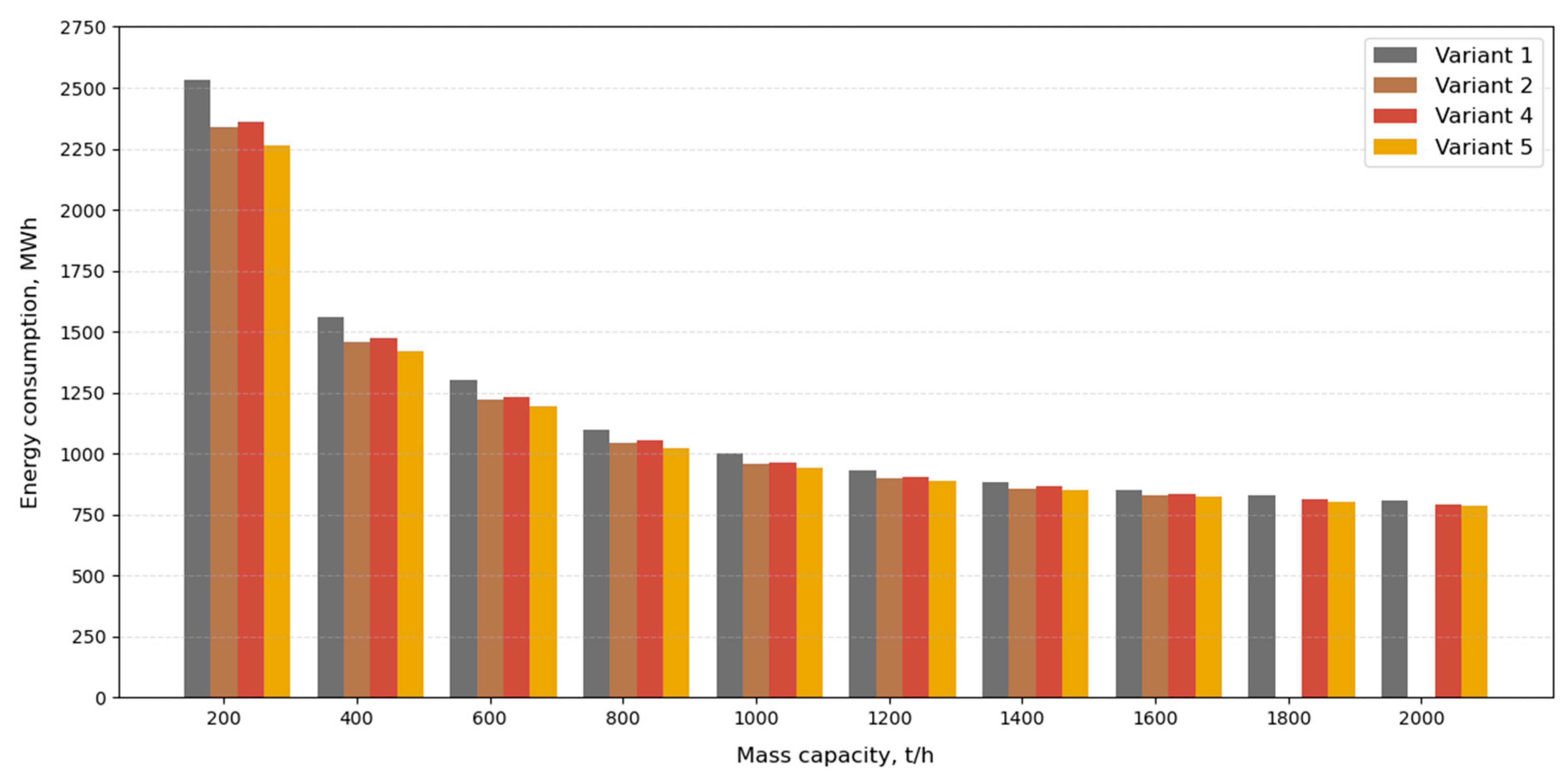

Figure 5 presents how much electric energy is required to transport 1 mln tonnes of bulk material for fixed mass flow rates from 200 to 2000 tonnes per hour. As shown in the bar chart, energy consumption significantly decreases as the mass capacity increases. For low throughputs (e.g. 200 t/h), the differences between variants are more significant - As the capacity increases, the total energy consumption levels off and the differences between the design variants become smaller. At high capacities (above 1400 t/h), all variants achieve similar energy consumption levels, indicating improved efficiency with higher loads.

In the next step, the percentage difference in energy consumption between four selected conveyor design variants was analyzed. These specific variants were selected because they meet the real achieved throughput capacity, making them suitable for real operational conditions (remembering that the variant 2 does not match the maximum capacity of 2000 t/h). The percentage difference in energy use was calculated based on the example histogram (

Table 4).

The comparison shows that variant 1 is the least energy efficient solution. It consumes more energy than all other variants. Variant 2 performs better than Variant 1 (−5.96%), but slightly worse than Variant 5 (+2.10%) and slightly better than Variant 4 (−1.01%). Variant 4 is more efficient than Variants 1 and slightly less efficient than Variant 2 and 5.

4. Discussion

Based on energy efficiency index only variant 5 should be chosen as a preferred solution. However, the calculated differences are small and in practice can be negligible. Therefore, the choice of a transportation system must take into account a comprehensive, multi-criteria assessment. The following aspects should be considered equally:

Energy efficiency – While this remains a key factor, the impact of secondary resistances (flexure resistances of bulk material on transfer points, bending resistances of belt on pulleys, friction resistances on scrapers and other belt cleaning devices) becomes less significant on longer routes.

Operational safety – Reliability and safety under actual mining conditions must be prioritized. The rising availability of monitoring gauges and diagnostic systems working on-line [

13,

39,

40,

42,

43,

45], as well as the development of periodical advanced tests of selected belt conveyor components [

12,

23,

41,

51,

58,

65] allow both the designers and the users of belt conveyors to investigate and implement more sophisticated solutions (like the proposed variant 4) instead of simply reuse of well known designs (here: variant 5).

Wear and maintenance – Shorter conveyors are subject to more frequent operational cycles, which leads to faster belt wear.

Mass of moving elements – A lighter belt can be advantageous at lower capacity, whereas higher capacity requires a stronger (and therefore heavier) belt, which may increase energy use and maintenance complexity but provides the performance margin that cannot be neglected according to possible increases of the required mine output – the conveyor line maximum capacity should not become a bottleneck of the future development of the new mine area.

Maintenance and monitoring – as mentioned in the previous chapter, any multiply -conveyor systems (instead of the single flight solutions) require supervision and maintenance of both the head station and the intermediate transfer point. Additionally, systems with intermediate drives may present challenges related to start-up and braking operations.

Therefore, the selection of the most appropriate conveyor system should be based on a holistic, multi-criteria evaluation rather than a single factor such as energy consumption.

5. Summary and Conclusions

The presented calculation results of the study alternative variants of underground long-distance belt conveyors for transporting copper ore are based on the requirements and technical constraints of the main haulage along the inclined route from the developed new mining fields in the KGHM mines in Poland. The accurate results of the required drive power with regard to the actual capacity and the different parameters of the analyzed conveyors have been done with the use of the dedicated, in-house developed software which allows to investigate the influence of the chosen conveyor components on its resistance to motion, hence - its energy consumption. Such analysis is not possible with the use of standard calculation methods.

The results have proved that there are no big differences of the energy efficiency among the analyzed variants. However, the careful comparison of them highlights the drawbacks of variants 2 and 3 (limited maximum capacity) and of the variant 5 (limited belt force margin for the maximum capacity for the conveyor 5b with the bigger material lift).

The obtained results underline the strong dependency of the average energy use by belt conveying on the actual mass flow. Conveyors, like the other transportation modes, are the most efficient when fully loaded. The main haulage conveyors are planned to be fed through a bunker. The bunker can and should be used for forming an even load close to the maximum capacity masses in order to increase the energy efficiency of belt conveyors. The savings of energy which can be obtained with the use of energy oriented operational control of transported mass are beyond the results that could be achieved by only the selection of energy efficient belts.

The paper does not deal with the investment and maintenance costs, because these are not disclosed by the company. Therefore, it has been assumed that the used components are the same unlike the number of the necessary units (drive units, take-up devices). The variants utilize, however, belts of various tensile strength which costs of purchase and splicing could also be different. On the other hand, the suppliers can treat an installation for a special, long-distance conveyor as a flagship of their portfolio that proves the high level of the achieved technology. The agreed price of a special belt could be therefore advantageous for mine.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. reports of the calculations of belt conveyors (QNK-TT), Excel spreadsheet with processed results

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, NSM, WK, RK; methodology, NSM, WK, RK.; software, WK.; validation, WK.; formal analysis, NSM, WK; investigation, NSM, WK.; resources, NSM WK, RK; data curation, NSM; writing—original draft preparation, NSM, WK.; writing—review and editing, NSM, WK, RK.; visualization, NSM.; supervision, RK.; project administration, RK; funding acquisition, RK. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research work was co-founded with the research subsidy of the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education granted for 2025.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon email contact with the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ghorbani, Y.; Nwaila, G.T.; Zhang, S.E.; Bourdeau, J.E.; Cánovas, M.; Arzua, J.; Nikadat, N. Moving towards Deep Underground Mineral Resources: Drivers, Challenges and Potential Solutions. Resour. Policy 2023, 80, 103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdu, A.; Nesbitt, P.; Brickey, A.; Newman, A.M. Operations Research in Underground Mine Planning: A Review. Inf. J. Appl. Anal. 2022, 52, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, R.; Boisvert, J. Optimization of Underground Mining Production Layouts Considering Geological Uncertainty Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Jennings, A. Impumelelo Coal Mine: Is Home to the World’s Longest Belt Conveyor. Min. Eng. 2016, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Dilefeld, M. Efficient TAKRAF Belt Conveyor Technology at One of the Largest Copper Mines in the World. TAKRAF TENOVA 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard, B.; O’Rourke, L. Optimisation of Overland Conveyor Performance. Aust. Bulk Handl. Rev. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Aispaugh, M.A.; Mess, T. Enhancing Overland Conveyor Possibilities. Trade J. 2006, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, M.J.; Wheeler, C.A.; Robinson, P.W.; Chen, B. Reducing the Energy Intensity of Overland Conveying Using a Novel Rail-Running Conveyor System. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2021, 35, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, V.F.N.; Figueiredo, J.R.; Hoz, R.C.D.L.; Botaro, M.; Chaves, L.S. A Mine-to-Crusher Model to Minimize Costs at a Truckless Open-Pit Iron Mine in Brazil. Minerals 2022, 12, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.; Davis, S.J.; Wolton, M. b Options for Long-Distance Large Capacity Conveying: A Comparison of Continuous Overland Conveying Systems. Bulk Solids Handl. 2012, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.P.; Wang, B.H.; Lu, S. Research and Design on Long-Distance Large-Capacity and High-Speed Belt Conveyor. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 538–541, 3070–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazej, R.; Jurdziak, L.; Kawalec, W. Operational Safety of Steel-Cord Conveyor Belts Under Non-Stationary Loadings. In International Conference on Condition Monitoring of Machinery in Non-Stationary Operation; Springer, 2014; pp. 473–481. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Wu, H.; Yin, H.; Wang, Y.; Shen, X.; Fang, Z.; Ma, D.; Miao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yan, M.; et al. Novel Mining Conveyor Monitoring System Based on Quasi-Distributed Optical Fiber Accelerometer Array and Self-Supervised Learning. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 221, 111697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousseau, T.; O’Shea, J.; Robinson, P.; Ryan, S.; Hoette, S.; Badat, Y.; Carr, M.; Wheeler, C. Optimizing Friction Losses of Conveyor Systems Using Large-Diameter Idler Rollers. Lubricants 2025, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, K.; Patil, S.V.; Venkataiah, C. The Vital Role of Overland Conveyors in the Transportation of Iron Ore: An Environmental Case Study in the NEB Range, Sandur Taluk, Karnataka. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Mathaba, T.; Xia, X. A Parametric Energy Model for Energy Management of Long Belt Conveyors. Energies 2015, 8, 13590–13608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawalec, W. Przenośniki Taśmowe Dalekiego Zasięgu. Transp. Przem. 2003, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Romani, N.K. Belt Speed and Tension Control on Long Conveyors: Application of Multiple Hydro-Viscous-Clutch Type Drives. Bulk Solids Handl. 2010, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Karolewski, B.; Ligocki, P. Modelling of Long Belt Conveyors. Eksploat. Niezawodn. 2014, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak, D. Tests of Rubber Properties under Cyclical Compression in Determining Indentation Rolling Resistance of Conveyor Belt. Mech. Time-Depend. Mater. 2025, 29, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambriško, Ľ.; Marasová, D.; Klapko, P. Energy Balance of the Dynamic Impact Stressing of Conveyor Belts. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavryukov, А.; Kolesnikov, M.; Zapryvoda, A.; Volters, A.; Samoilenko, M. Devising a Procedure for Calculating the Belt Tension of a Conveyor with a Stopped Drive When Changing the Transportation Length. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2025, 1, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajda, M.; Błażej, R.; Jurdziak, L. Analysis of Changes in the Length of Belt Sections and the Number of Splices in the Belt Loops on Conveyors in an Underground Mine. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 101, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, D.; Wheeler, C. Measurement and Simulation of the Bulk Solid Load on a Conveyor Belt during Transportation. Powder Technol. 2017, 307, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajda, M.; Jurdziak, L.; Konieczka, Z. Impact of Monthly Load Variability on the Energy Consumption of Twin Belt Conveyors in a Lignite Mine. Energies 2025, 18, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Gong, H.; Sun, W.; Yan, Q.; Shi, K.; Du, G. Active Speed Control of Belt Conveyor with Variable Speed Interval Based on Fuzzy Algorithm. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2024, 19, 1499–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Pang, Y.; Lodewijks, G.; Liu, X. Healthy Speed Control of Belt Conveyors on Conveying Bulk Materials. Powder Technol. 2018, 327, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Yan, C.; Wu, Q.; Wang, T. Dynamic Behaviour of a Conveyor Belt Considering Non-Uniform Bulk Material Distribution for Speed Control. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, D.; Katterfeld, A. Simulation of Transfer Chutes. In Simulations in Bulk Solids Handling; Wiley, 2023; pp. 41–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs-Capdeville, P.; Kuang, S.; Yu, A. Unrevealing Energy Dissipation during Iron Ore Transfer through Chutes with Different Designs. Powder Technol. 2024, 435, 119446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortnowski, P.; Gładysiewicz, A.; Gładysiewicz, L.; Król, R.; Ozdoba, M. Conveyor Intermediate TT Drive with Power Transmission at the Return Belt. Energies 2022, 15, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanus, M.; Hoffmann, A.; Overmeyer, L.; Ponick, B. Linear Direct Drive for Light Conveyor Belts to Reduce Tensile Forces. 2020; pp. 398–406. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, C.; Overmeyer, L. Driving Idlers as an Intermediate Drive Solution for Conveyor Belt Systems. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błażej, R.; Jurdziak, L.; Kirjanów-Błażej, A.; Bajda, M.; Olchówka, D.; Rzeszowska, A. Profitability of Conveyor Belt Refurbishment and Diagnostics in the Light of the Circular Economy and the Full and Effective Use of Resources. Energies 2022, 15, 7632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawalec, W.; Król, R.; Suchorab, N. Regenerative Belt Conveyor versus Haul Truck-Based Transport: Polish Open-Pit Mines Facing Sustainable Development Challenges. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Huang, W.; Zhang, S. Energy Cost Optimal Operation of Belt Conveyors Using Model Predictive Control Methodology. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 105, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gao, X.; Zheng, H. Operation Parameters Optimization Method of Coal Flow Transportation Equipment Based on Convolutional Neural Network. Min. Metall. Explor. 2024, 41, 1793–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeinsch, T.; Sader, M.; Noack, R.; Barber, K.; Ding, S.X.; Zang, P.; Zhong, M. A Robust Model-Based Information System for Monitoring and Fault Detection of Large Scale Belt Conveyor Systems. In Proceedings of the 4th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation (Cat. No.02EX527); IEEE, 2002; pp. 3283–3287. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Fu, S.; Liu, F.; Cheng, X. Intelligent Fault Diagnosis of Belt Conveyor Rollers Using a Polar KNN Algorithm with Audio Features. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 168, 109101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trybała, P.; Blachowski, J.; Błażej, R.; Zimroz, R. Damage Detection Based on 3D Point Cloud Data Processing from Laser Scanning of Conveyor Belt Surface. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olchówka, D.; Blażej, R.; Jurdziak, L. Selection of Measurement Parameters Using the DiagBelt Magnetic System on the Test Conveyor. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2198, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Yuan, J.; Shen, J.; Wheeler, C.; Liu, Z.; Yan, J. A Visual Detection Method for Conveyor Belt Misalignment Based on the Improved YOLACT Network. Part. Sci. Technol. 2024, 42, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.; Huang, S. Research on a System for the Diagnosis and Localization of Conveyor Belt Deviations in Belt Conveyors. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 035110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupkar, R.; Kumar, D.; Sakhale, C.; Shelare, S. Optimizing Belt Tension and Stretch Dynamics: A Modeling Approach for Medium-Duty Conveyor Systems. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 025413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, S. Research on the Control System of the Multi-Point Driving Belt Conveyor Tension Device. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Big Data, Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things Engineering (ICBAIE); IEEE, June 2020; pp. 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, G.; Meng, G. Dynamic Characteristic Analysis and Startup Optimization Design of an Intermediate Drive Belt Conveyor with Non-Uniform Load. Sci. Prog. 2020, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurdziak, L.; Błażej, R.; Kirjanów-Błażej, A.; Rzeszowska, A. Transverse Profiles of Belt Core Damage in the Analysis of the Correct Loading and Operation of Conveyors. Minerals 2023, 13, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Pang, Y.; Lodewijks, G. Theoretical and Experimental Determination of the Pressure Distribution on a Loaded Conveyor Belt. Measurement 2016, 77, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Zhou, F.; Fu, Z.Y. Soft Start Design of Controlled Transmission for Belt Conveyor. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 229–231, 2459–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, C. AMT Starting Control as a Soft Starter for Belt Conveyors Using a Data-Driven Method. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulinowski, P.; Kasza, P.; Zarzycki, J. The Analysis of Effectiveness of Conveyor Belt Tensioning Systems. New Trends Prod. Eng. 2020, 3, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, V.; Fedorko, G.; Stehlíková, B.; Tomašková, M.; Hulínová, Z. Analysis of Asymmetrical Effect of Tension Forces in Conveyor Belt on the Idler Roll Contact Forces in the Idler Housing. Measurement 2014, 52, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, D.; Hardygóra, M. Aspects of Selecting Appropriate Conveyor Belt Strength. Energies 2021, 14, 6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajda, M. Predicting the Working Time of Multi-Ply Conveyor Belt Splices in Underground Mines. Min. Sci. 2024, 31, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrejiova, M.; Grincova, A.; Marasova, D. Analysis of Tensile Properties of Worn Fabric Conveyor Belts with Renovated Cover and with the Different Carcass Type. Eksploat. Niezawodn. – Maint. Reliab. 2020, 22, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, R.B. Belting the Worlds’ Longest Single Flight Conventional Conveyor. Bulk Solids Handl. 2008, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Reicks, A.V.; Rudolphif, T.J. The Importance and Prediction of Tension Distribution Around the Conveyor Belt Path. In Proceedings of the SME Annual meeting, Denver, USA; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Błażej, R.; Jurdziak, L.; Rzeszowska, A. Sensor-Based Diagnostics for Conveyor Belt Condition Monitoring and Predictive Refurbishment. Sensors 2025, 25, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gładysiewicz, L.; Kawalec, W. Selection of Distance Belt Conveyors for Underground Copper Mine. In Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on Mine Planning and Equipment Selection, Torino, Italy; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gladysiewicz, L. Belt conveyors. Theory and calculations; Publishing House of Wrocław University of Technology, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kawalec, W.; Kulinowski, P. Obliczenia Przenośników Taśmowych. Transp. Przem. 2007, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Król, R. Metody badań i doboru elementów przenośnika taśmowego z uwzględnieniem losowo zmiennej strugi urobku; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej: Wrocław, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kulinowski, P. Simulation Studies as the Part of an Integrated Design Process Dealing with Belt Conveyor Operation. Eksploat. Niezawodn. 2013, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Konieczna-Fuławka, M. New Theoretical Method for Establishing Indentation Rolling Resistance. Min. Sci. 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, R.; Gladysiewicz, L.; Kaszuba, D.; Kisielewski, W. New Quality Standards of Testing Idlers for Highly Effective Belt Conveyors. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 95, 042055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchorab-Matuszewska, N. Data-Driven Research on Belt Conveyors Energy Efficiency Classification. Arch. Min. Sci. 2024, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawalec, W.; Suchorab, N.; Konieczna-Fuławka, M.; Król, R. Specific Energy Consumption of a Belt Conveyor System in a Continuous Surface Mine. Energies 2020, 13, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashan, A.J.; Lay, J.; Wiewiora, A.; Bradley, L. The Innovation Process in Mining: Integrating Insights from Innovation and Change Management. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediriweera, A.; Wiewiora, A. Barriers and Enablers of Technology Adoption in the Mining Industry. Resour. Policy 2021, 73, 102188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).