Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

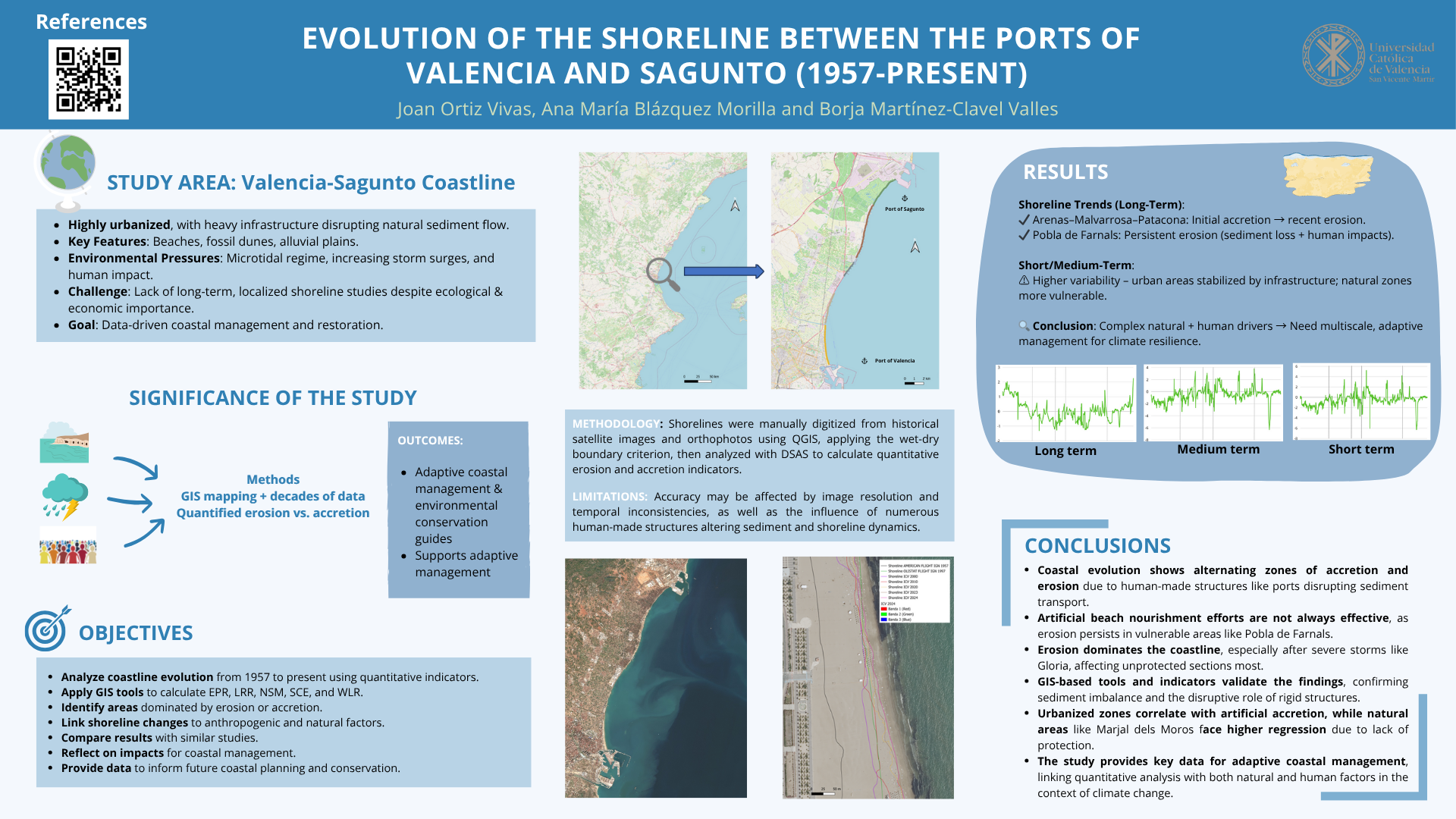

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

- (a)

- End Point Rate (EPR): Calculates the total change in the shoreline by dividing the net shoreline movement (NSM) by the number of years between the first and last dates of the analysis, expressed in meters per year. Its main strength lies in its simplicity of calculation. However, since it is based only on two time points, it does not consider the available intermediate data, which can limit its ability to adequately reflect changes or trends over time. For this reason, it is common to compare its results with more robust methods, such as linear regression or weighted regression, which take multiple observations into account [41].

- (b)

- Linear Regression Rate (LRR): Estimates the overall trend of coastal change by fitting a linear regression line to all available shoreline positions. In this calculation, the linear regression is derived from the intersection points of each transect, and the slope represents the rate of change expressed in meters per year. It is a useful tool for predicting how the coastline may evolve in the future and allows for assessing whether there is a clear relationship between the passage of time and shoreline movement. However, it can be affected by outliers that skew the results and, in some cases, tends to produce a lower rate of change compared to other methods [17].

- (c)

- Net Shoreline Movement (NSM): Represents the distance (m) between the oldest and most recent shoreline positions, without considering the time elapsed [32].

- (d)

- Shoreline Change Envelope (SCE): Indicates the maximum distance (m) between the most distant shoreline positions, regardless of their temporal order [40].

- (e)

- Weighted Linear Regression (WLR): Similar to LRR, but incorporates the uncertainty of each shoreline position as a weighting factor in the analysis, reducing the impact of less precise data and improving the reliability of the statistical fit [40]. It is used to represent how the shoreline has evolved over time. This method allows identification of areas that have changed more rapidly, helping to highlight zones that may be more vulnerable to erosion [17,42].

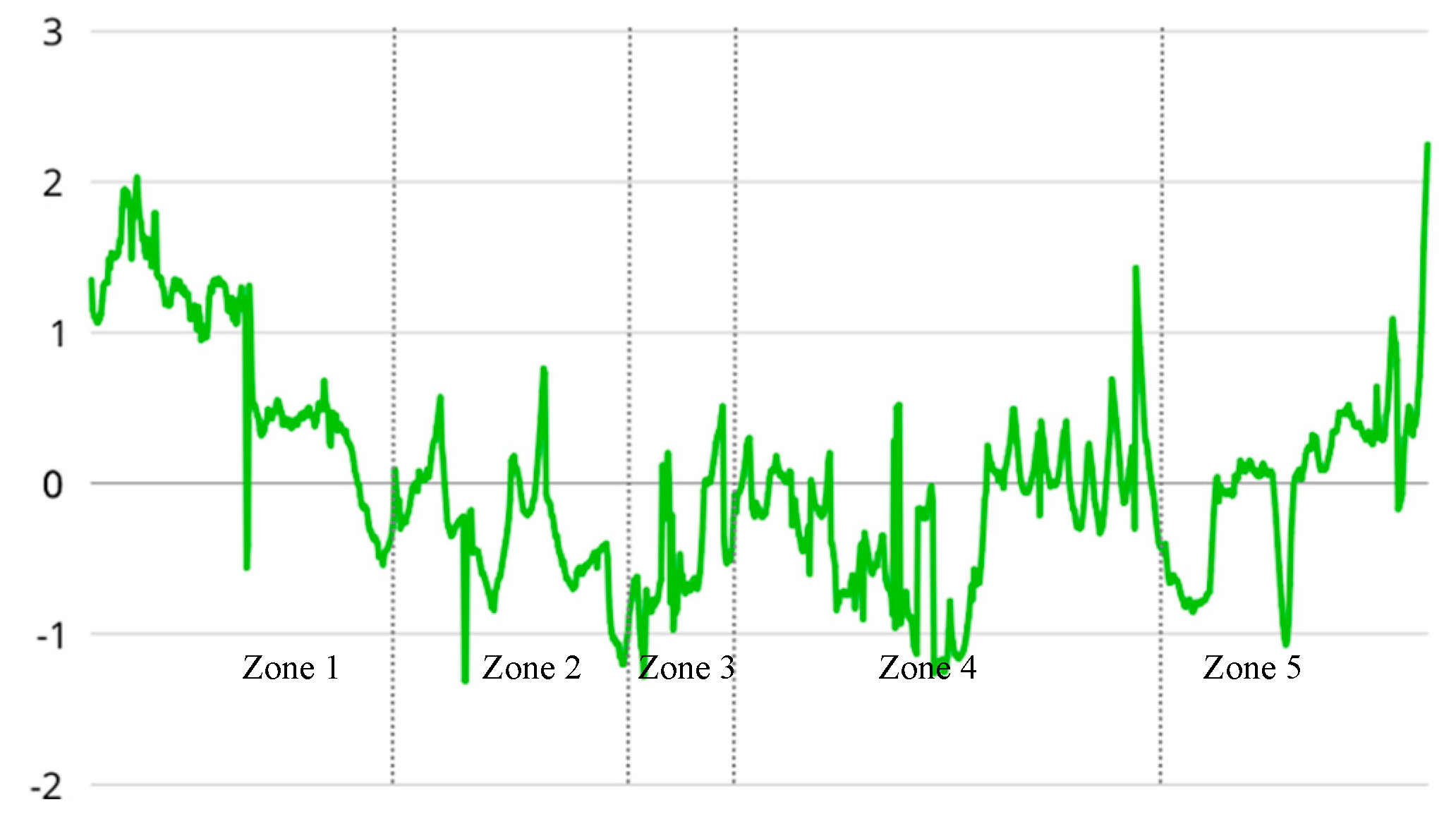

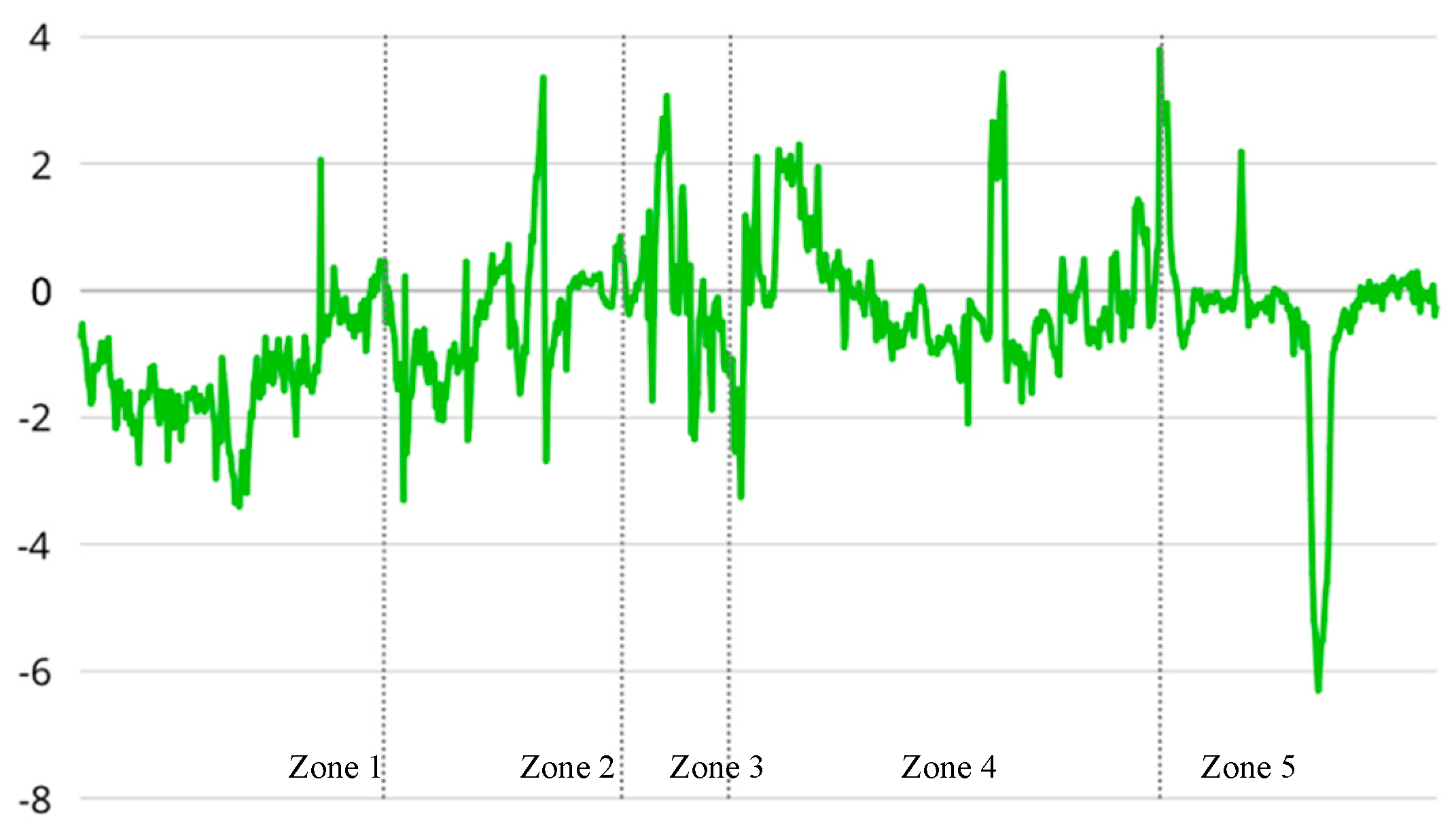

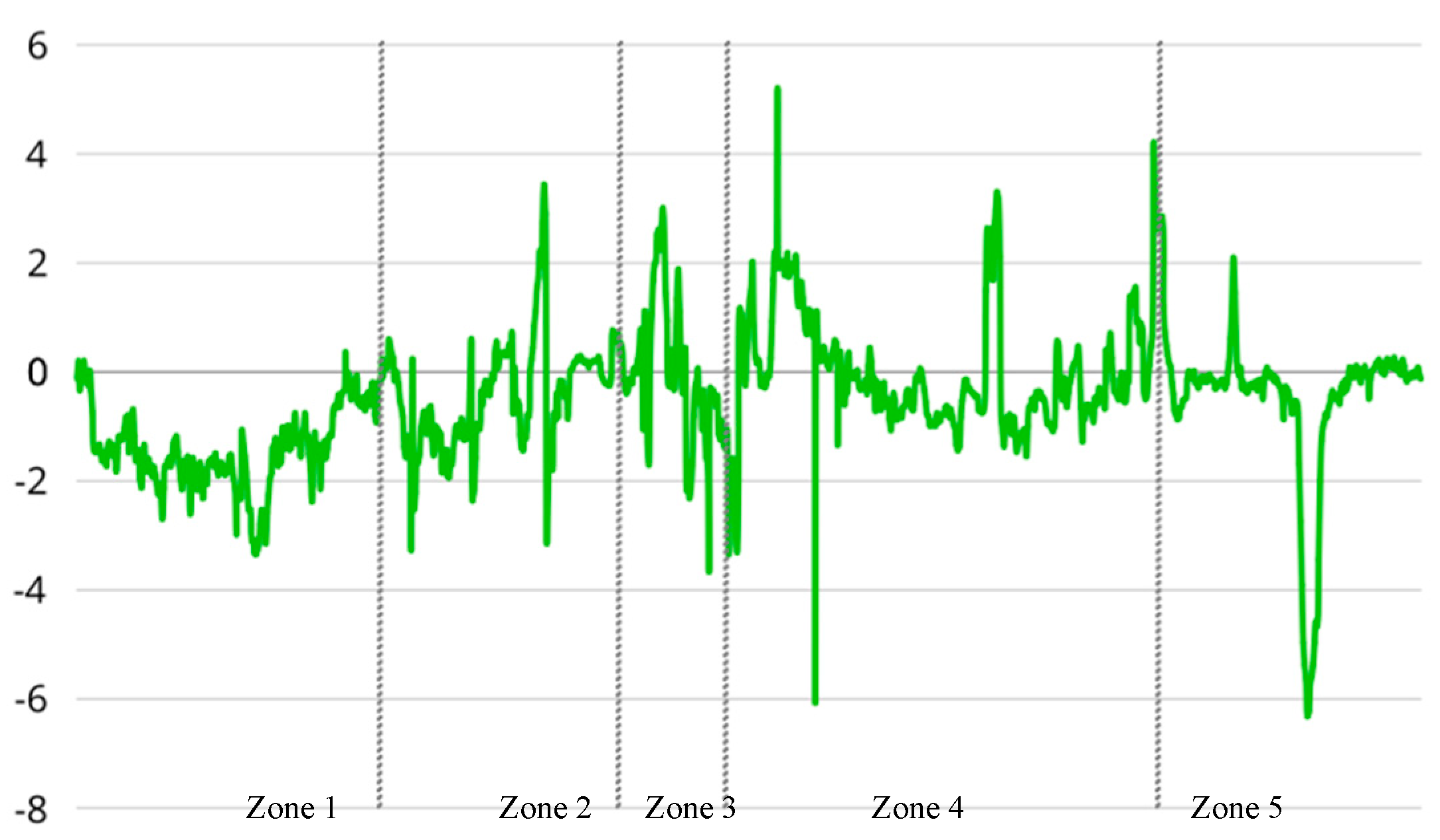

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparative Analysis of Average Values by Areas and Time Scales

5.2. Development of the Coastline Between the Ports of Sagunto and Valencia

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CGAT-UPV | Geoenvironmental Cartography and Remote Sensing Group (Universitat Politècnica de València) |

| DSAS | Digital Shoreline Analysis System |

| EPR | End Point Rate |

| EPSG | European Petroleum Survey Group |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| ICV | Valencian Cartographic Institute (Instituto Cartográfico Valenciano) |

| IGME | Spanish Geological and Mining Institute (Instituto Geológico y Minero de España) |

| IGN | National Geographic Institute (Instituto Geográfico Nacional, Spain) |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| LRR | Linear Regression Rate |

| MTTECO | Ministry for Ecological Transition (Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica, Spain) |

| NSM | Net Shoreline Movement |

| QGIS | Quantum Geographic Information System |

| RTK-GPS | Real-Time Kinematic Global Positioning System |

| SCE | Shoreline Change Envelope |

| SS | Storm Surge |

| UTM | Universal Transverse Mercator |

| WLR | Weighted Linear Regression |

References

- Pardo-Pascual, J. E.; Palomar-Vázquez, J.; Cabezas-Rabadán, C. Estudio de los cambios de posición de la línea de costa en las playas del segmento València-Cullera (1984-2020) a partir de imágenes de satélite de resolución media de libre acceso. Cuadernos de Geografía de la Universitat de València 2022, 108, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Villalobos, C.; Gracia Prieto, F.J.; Benavente González, J. Evolución histórica de la línea de costa en el sector meridional de la Bahía de Cádiz. Revista Atlántica-Mediterránea de Prehistoria y Arqueología Social 2009, 11, 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra Marinas, D.; Belmonte Serrato, F.; Gomariz Castillo, F.; Pérez Cutillas, P. Evolución de la línea de costa en la Región de Murcia (1956-2013). Geo-Temas 2015, 15, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cendrero Uceda, A.; Sánchez-Arcilla Conejo, A.; Zazo Cardeña, C. Impactos sobre las zonas costeras. Evaluación preliminar de los impactos en España por efecto del cambio climático 2005, 11, 469–524. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Santalla, I.; Roca, M.; Martínez-Clavel, B.; Pablo, M.; Moreno-Blasco, L.; Blázquez, A.M. Coastal changes between the harbours of Castellón and Sagunto (Spain) from the mid-twentieth century to present. Regional Studies in Marine Science 2021, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, I.; Montoya, I.; Sánchez, M.J.; Carreño, F. Geographic Information Systems applied to Integrated Coastal Zone Management. Geomorphology 2009, 107, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rojo, C.N.; Pérez-Cayeiro, M.L.; Chica-Ruiz, J.A. Adaptation to climate change in coastal areas of the European Union. An evaluation of plans and strategies. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sardá, R.; Mora, J.; Avila, C. Tourism development in the Costa Brava (Girona, Spain) - how integrated coastal zone management may rejuvenate its lifecycle. Managing European Coasts 2005, 291–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, E.; Sardá, R.; Jiménez, J.A.; Mora, J.; Ávila, C. Beyond performance assessment measurements for beach management: Application to Spanish Mediterranean beaches. Coast. Manag. Int. J. Mar. Environ. Resour. Law Soc. 2007, 36, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olcina Cantos, J. Cambio y riesgos climáticos en España. Investigaciones Geográficas 2009, 49, 179–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza, E.; Jiménez, J.A.; Sardá, R. A critical assessment of beach management on the Catalan coast. Ocean & coastal management 2008, 51, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatchez, P.; Fraser, C. Evolution of coastal defence structures and consequences for beach width trends, Québec, Canada. J. Coast. Res. 2012, 285, 1550–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaiah, K.; Ramana Murty, M.V.; R. , Kanungo, A.; Ramana, K.V. Shoreline evolution along Uppada coast in andhra pradesh using multi temporal satellite images and model based approach. Ramana Indian Journal of Geosynthetics and Ground Improvement 2019, 8, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa Montero, V.; Rodríguez Santalla, I. Evolución costera del tramo comprendido entre San Juan de los Terreros y Playas de Vera (Almería). Revista de la Sociedad Geológica de España 2009, 22, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.L.; Gary, A. Calculating Long-Term Shoreline Recession Rates Using Aerial Photographic and Beach Profiling Techniques. Journal of Coastal Research 1990, 6, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Boak, E.H.; Turner, I.L. Shoreline definition and detection: A review. Journal of Coastal Research 2005, 21, 688–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Prieto, J.A.; Roig Munar, F.X.; Rodríguez Perea, A.; Pons Buades, G.X.; Mir Gual, M.; Gelabert Ferrer, B. Análisis de la evolución histórica de la línea de costa de la playa de Es Trenc (Mallorca): causas y consecuencias. GeoFocus: Revista Internacional de Ciencia y Tecnología de la Información Geográfica 2018, 21, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Pascual, J. E.; Sanjaume Saumell, E. Análisis multiescalar de la evolución costera. Cuadernos de Geografía de la Universitat de València, /70. [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Pascual, J.E.; Almonacid-Caballer, J.; Ruiz, L.A.; Palomar-Vázquez, J. Automatic extraction of shorelines from Landsat TM and ETM+ multi-temporal images with subpixel precision. Remote Sensing of Environment 2012, 123, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almonacid-Caballer, J.; Sánchez-García, E.; Pardo-Pascual, J.E.; Balaguer-Beser, A.A.; Palomar-Vázquez, J. Evaluation of annual mean shoreline position deduced from Landsat imagery as a mid-term coastal evolution indicator. Marine Geology 2016, 372, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Pascual, J.E.; Roca Moya, R.; Segura-Beltran, F. Análisis de la evolución de la línea de costa entre Alcossebre y Orpesa a partir de fotografía aérea (1956-2015). Cuad. De Geogr. De La Univ. De València 2019, 102, 39–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leatherman, S.P.; Pajak, M.J. The High Water Line as Shoreline Indicator. Journal of Coastal Research 2002, 18, 329–337. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Pascual, J.E.; Carmona, P.; Segura, F.; López García, M.J. Recent coast changes in the Gulf of Valencia. Z. Geomorph. N. F 1996, 102, 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjaume, E.; Pardo-Pascual, J.E. Erosion by human impact on the Valencian coastline (E of Spain). Coastal Erosion (Proceedings). Spain Journal of Coastal Research 2005, 49, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas-Rabadán, C.; Pardo-Pascual, J.E.; Palomar-Vázquez, J. A remote monitoring approach for coastal engineering projects. Scientific reports 2025, 15, 2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, C.V.; Gontz, A.M.; Tenenbaum, D.E.; Berkland, E.P. Coastal hazard vulnerability assessment of sensitive historical sites on Rainsford Island, Boston Harbor, Massachusetts. Journal of Coastal Research 2012, 28, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Moran, C.A. , (2003). Spatio-temporal analysis of Texas shoreline changes using GIS technique. Tesis Doctoral, Master of Science, Texas A&M University.

- Conesa, P.; Ignacio, J.; Pomares, A. ; Luis, Úbeda, L.; Isabel, Peris, S.; Cristobal, J. La evolución de la línea de costa en las playas de arena del Levante mediterráneo. XIV Jornadas Españolas de Ingeniería de Costas y Puertos.

- Laitinen, S.; Neuvonen, A. BALTICSEAWEB: an information system about the Baltic Sea environment. Advances in environmental research 2001, 5, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.M.; Spencer, T. Temporal and spatial variations in recession rates and sediment release from soft rock cliffs, Suffolk coast, UK. Geomorphology 2010, 124, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Villanueva, R.; Costas, S.; Pérez-Arlucea, M.; Jerez, S.; Trigo, R.M. Impact of atmospheric circulation patterns on coastal dune dynamics, NW Spain. Geomorphology 2013, 185, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedotun, T.D.T. Shoreline Geometry DSAS as a Tool for Historical Trend Analysis. Geomorphological Techniques 2014, 3, 2.2. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto geológico y minero de España. Available online: https://info.igme.es/cartografiadigital/datos/Geo50/mapas/d7_PS50/Editado722_PSGeologico50.

- Toledo, I.; Pagán, J.I. ; López; I.; Olcina, J.; Aragonés L. Storm surge in Spain: Factors and effects on the coast. Marine Geology. [CrossRef]

- Puertos del Estado. Available online: https://portus.puertos.

- Griggs, G.; Reguero, B.G. Coastal Adaptation to Climate Change and Sea-Level Rise. Water 2021, 13, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajuntament de Puçol: AE-Agró amplía el proyecto de restauración de la flora dunar de la playa de Puçol con la ayuda de 50 voluntarios. Available online: https://archivo.xn--puol-1oa.es/index.php/es/component/content/article? 1407.

- Ajuntament de Sagunt: Se terminan los trabajos de aportación de áridos al litoral de la Marjal dels Moros. Available at: https://aytosagunto.

- Ojeda Zújar, J. Métodos para el cálculo de la erosión costera. Revisión, tendencias y Propuesta. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles. 30, 103-118.

- Himmelstoss, E.A. , Henderson, R.E., Farris, A.S., Kratzmann, M.G., Bartlett, M.K., Ergul, A., McAndrews, J., Cibaj, R., Zichichi, J.L. y Thieler, E.R. (2024). Digital Shoreline Analysis System version 6.0: U.S. Geological Survey 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R. , Fenster, M.S. y Holmes, S.J. Temporal Analysis of Shoreline Recession and Accretion. Journal of Coastal Research 1991, 7, 723–744. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Arcilla, A.; Jiménez, J.A.; Valdemoro, H. The Ebro Delta: morphodynamics and vulnerability. Journal of Coastal Research 1998, 14, 754–772. [Google Scholar]

- Aranegui Gascó, C.; Ruiz Pérez, J.M.; Carmona González, P. El humedal del puerto de Arse-Saguntum. Estudio geomorfológico y sedimentológico. SAGVNTVM (P.L.A.V.).

- Reparación de la mota de protección del Marjal dels Moros. Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/costas/temas/proteccion-costa/actuaciones-proteccion-costa/valencia/460334-mota-marjal-mors.

| Name | Date | Spatial resolution | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| American flight | 01/01/1957 | 0.5 m | IGN |

| OLISTAT flight | 15/10/1997 | 1 m | IGN |

| 2000 | 15/08/2000 | 0.5 m | ICV |

| 2004 | 22/06/2004 | 0.5 m | ICV |

| 2006 | 25/07/2006 | 0.5 m | ICV |

| 2008 | 03/09/2008 | 0.5 m | ICV |

| 2010 | 29/11/2010 | 0.25 m | ICV |

| 2012 | 07/07/2012 | 0.5 m | ICV |

| 2015 | 19/06/2015 | 0.25 m | ICV |

| 2017 | 16/07/2017 | 0.25 m | ICV |

| 2018 | 19/07/2018 | 0.25 m | ICV |

| 2019 | 06/06/2019 | 0.25 m | ICV |

| 2020 | 16/05/2020 | 0.25 m | ICV |

| 2021 | 15/06/2021 | 0.25 m | IGN |

| 2022 | 25/05/2022 | 0.25 m | ICV |

| 2023 | 11/06/2023 | 0.25 m | ICV |

| 2024 | 11/07/2024 | 0.25 m | ICV |

| Nº | Transects | Name of the zone | Extension (m) | Limits | Sediment | Main anthropic structures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-215 | Arenas - Malvarrosa - Patacona | 4.280 | 39° 27ʹ 47.16″ N 0° 19ʹ 11.76″ W 39° 30ʹ 4.43″ N 0° 19ʹ 22.70″ W |

Fine sands and pebbles |

Port of Valencia 1 breakwater Seafront promenade |

| 2 | 216-386 | Port Saplaya | 3.400 | 39° 30ʹ 8.67″ N 0° 19ʹ 22.27″ W 39° 31ʹ 33.48″ N 0° 18ʹ 50.16″ W |

Fine sands and gravels |

4 transversal groynes 2 breakwaters Seafront promenade |

| 3 | 387-481 | Pobla de Farnals | 1.920 | 39° 32ʹ 52.76″ N 0° 17ʹ 52.55″ W 39° 33ʹ 37.87″ N 0° 17ʹ 5.84″ W |

Fine sands and pebbles |

Marina 4 groynes 3 breakwaters Seafront promenade |

| 4 | 482-787 | Puzol | 6.220 | 39° 33ʹ 51.84″ N 0° 16ʹ 55.12″ W 39° 36ʹ 55.03″ N 0° 15ʹ 31.08″ W |

Fine sands and pebbles |

18 groynes 1 breakwater Seafront promenade |

| 5 | 788-1000 | Marjal dels Moros | 3.580 | 39° 36ʹ 55.03″ N 0° 15ʹ 31.08″ W 39° 38ʹ 18.85″ N 0° 13ʹ 54.07″ W |

Fine sands |

Port of Sagunto 1 embankment |

| 1957-2024 | ||||||

| Nº | Zona | x̄ EPR | x̄ LRR | x̄ NSM | x̄ SCE | x̄ WLR |

| 1 | Arenas - Malvarrosa - Patacona | 0.963 | 0.877 | 58.422 | 76.313 | 0.812 |

| 2 | Port Saplaya | -0.250 | -0.274 | -16.155 | 47.633 | -0.238 |

| 3 | Pobla de Farnals | -0.709 | -0.570 | -43.989 | 68.882 | -0.388 |

| 4 | Puzol | -0.271 | -0.230 | -18.361 | 51.295 | -0.194 |

| 5 | Marjal dels Moros | -0.004 | 0.031 | -2.367 | 33.948 | -0.007 |

| 1997-2024 | ||||||

| Nº | Zona | x̄ EPR | x̄ LRR | x̄ NSM | x̄ SCE | x̄ WLR |

| 1 | Arenas - Malvarrosa - Patacona | -0.396 | -1.468 | -3.670 | 28.398 | -1.468 |

| 2 | Port Saplaya | -0.084 | -0.448 | -0.084 | -0.084 | -0.084 |

| 3 | Pobla de Farnals | -0.939 | -0.134 | -8.509 | 35.490 | -0.134 |

| 4 | Puzol | 0.577 | 0.049 | 5.206 | 23.888 | 0.049 |

| 5 | Marjal dels Moros | -0.506 | -0.522 | -4.549 | 9.211 | -0.522 |

| 2015-2024 | ||||||

| Nº | Zona | x̄ EPR | x̄ LRR | x̄ NSM | x̄ SCE | x̄ WLR |

| 1 | Arenas - Malvarrosa - Patacona | -0.267 | -1.433 | -2.416 | 28.811 | -1.433 |

| 2 | Port Saplaya | -0.087 | -0.450 | -0.783 | 21.781 | -0.450 |

| 3 | Pobla de Farnals | -1.047 | -0.227 | -9.288 | 36.011 | -0.227 |

| 4 | Puzol | 0.605 | 0.060 | 5.550 | 24.496 | 0.060 |

| 5 | Marjal dels Moros | -0.510 | -0.529 | -4.623 | 9.226 | -0.529 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).