Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Tubular Vacuolar System

2.1. Methods of Labeling and Microscopic Visualization of the Fungal Vacuolar System

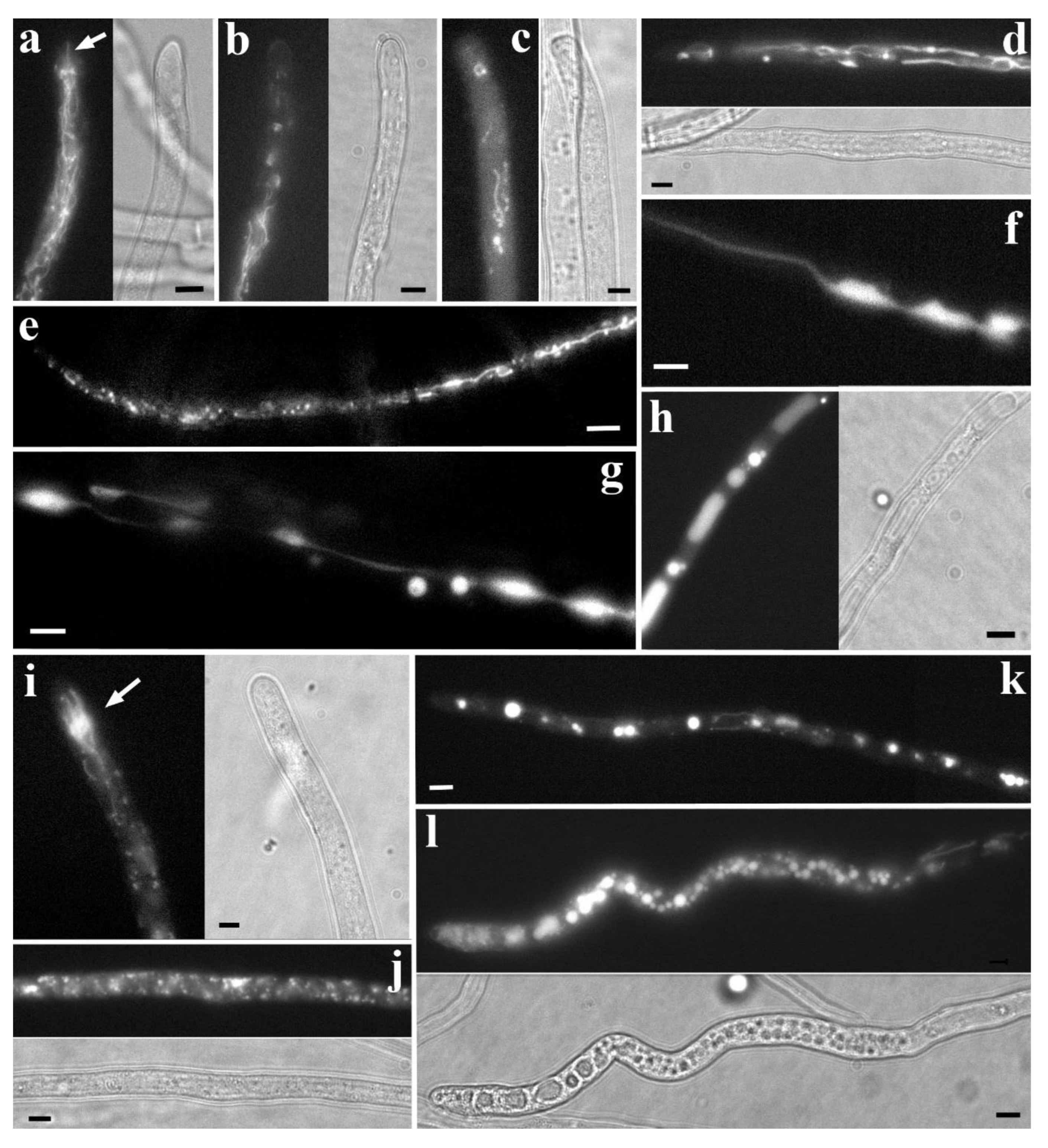

2.2. Morphotypes of the Tubular Vacuolar System and Their Variants

2.3. Molecular Mechanisms of Vacuole Morphogenesis, Influence of the Cytoskeleton on the Vacuolar System

2.4. Physiological Functions of the Vacuolar System of Fungi

2.4.1. General Functions of Different Types of Vacuoles

2.4.2. Proposed Functions of Tubular Vacuoles

3. Filamentous, Tubular, Network and Super-Elongated Mitochondria

3.1. Methods of Labeling and Microscopic Visualization of the Fungal Mitochondrial System

3.2. Mitochondrial Morphology and Diversity, Morphotypes of the Fungal Mitochondrial System

3.3. Molecular Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Morphogenesis and Dynamic, Influence of the Cytoskeleton on the Mitochondrial System

3.4. Physiological Functions of the Mitochondrial System in Fungi, Division of Labor, the Meaning of Fragmentation and Fusion Cycles

4. Fungal Endoplasmic Reticulum

4.1. Morphology, Diversity and Intrahyphal Topology of Fungal Endoplasmic Reticulum

4.2. Molecular Mechanisms of Morphogenesis, Influence of the Cytoskeleton, and Physiological Functions of the Fungal Endoplasmic Reticulum

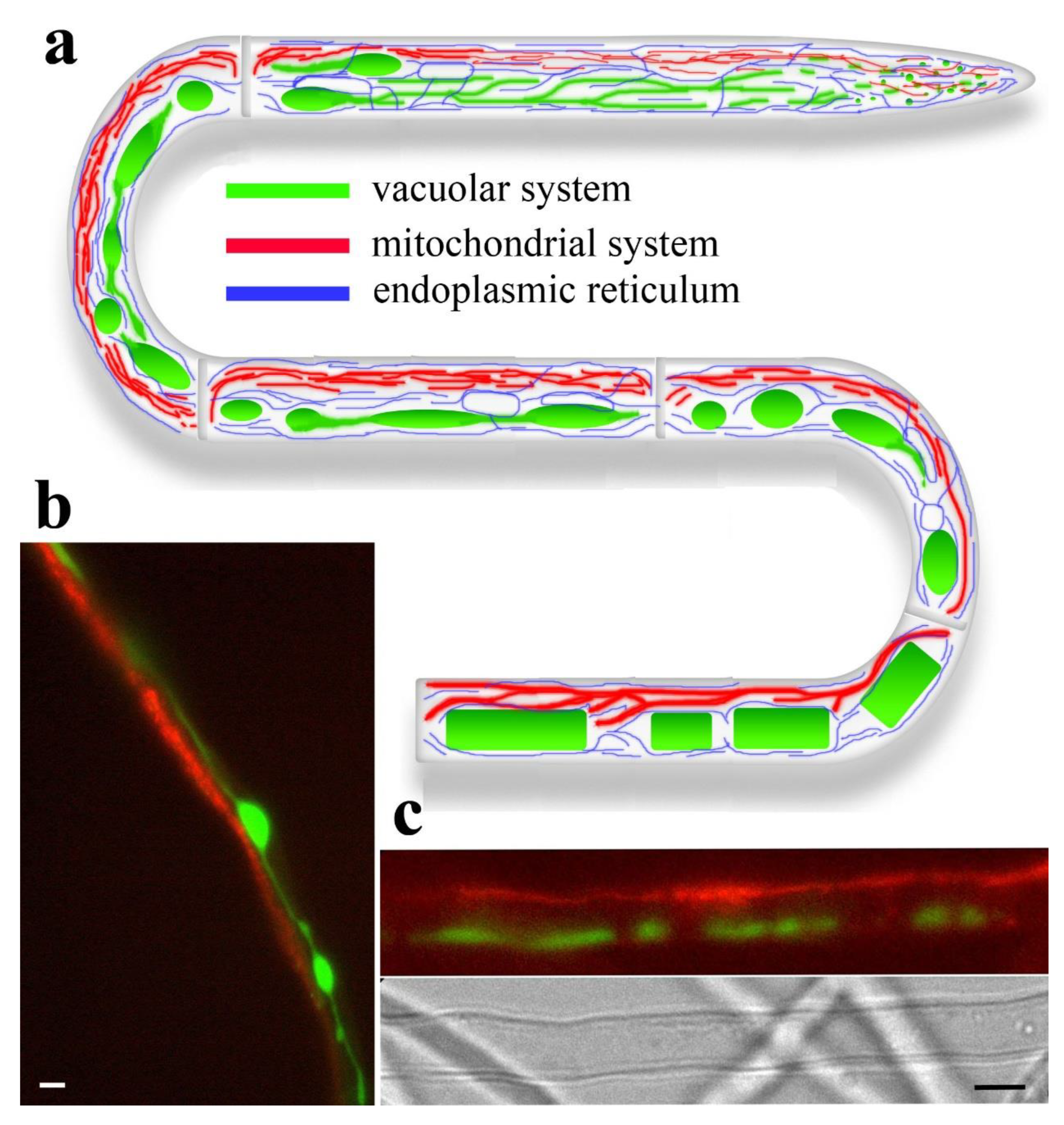

5. Interaction of Tubular and Tubular-Lamellar Systems with Each Other, and Their Functions as a Single Endomembrane Complex in Fungi

5.1. Vacuolar and Mitochondrial Tubular Systems

5.2. The Endoplasmic Reticulum Accompanies, Isolates, and Controls the Vacuolar and Mitochondrial Tubular Systems

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations

References

- Abadeh A, Lew RR. 2013. Mass flow and velocity profiles in Neurospora hyphae: partial plug flow dominates intrahyphal transport. Microbiol 159:2386–2394. [CrossRef]

- Allaway WG, Ashford AE, Heath IB, Hardham AR. 1997. Vacuolar reticulum in oomycete hyphal tips: an additional component of the Ca2+ regulatory system? Fungal Genet Biol 22:209–20. [CrossRef]

- Allaway WG, Ashford AE. 2001. Motile tubular vacuoles in extramatrical mycelium and sheath hyphae of ectomycorrhizal systems. Protoplasma 215:218–25. [CrossRef]

- Armentrout VN, Smith GG, Wilson CL. 1968. Spherosomes and mitochondria in the living fungal cell. Am J Bot 55:1062–7. [CrossRef]

- Ashford AE, Orlovich DA. 1995. Vacuoles, phosphorus and endosomes in fungal hyphae. In Current Topics of Plant Physiology. Pollen–Pistil Interactions and Pollen Tube Growth. Kao TH, Stephenson AG, Eds. pp. 135–149. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD.

- Ashford, AE. 1998. Dynamic pleiomorphic vacuole systems: are they endosomes and transport compartments in fungal hyphae? Adv Bot Res 28:119–59. [CrossRef]

- Ashford AE, Cole L, Hyde GJ. 2001. Motile Tubular Vacuole Systems. In: Howard RJ, Gow NAR. (eds) Biology of the Fungal Cell. The Mycota 8. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Ashford, A. Tubular vacuoles in arbuscular mycorrhizas. 2002. New Phytol 154:545–547. [CrossRef]

- Askew, DS. 2014. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and fungal pathogenesis converge. Virulence 5:331–3. [CrossRef]

- Benhamou RI, Jaber QZ, Herzog IM, Roichman Y, Fridman M. 2018. Fluorescent tracking of the endoplasmic reticulum in live pathogenic fungal cells. ACS Chem Biol 13:3325–32. [CrossRef]

- Bera A, Gupta Jr ML. 2022. Microtubules in microorganisms: how tubulin isotypes contribute to diverse cytoskeletal functions. Front Cell Develop Biol 10:913809. [CrossRef]

- Berepiki A, Lichius A and Read ND. 2011. Actin organization and dynamics in filamentous fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:876–887. [CrossRef]

- Besserer A, Bécard G, Jauneau A, Roux C, Séjalon-Delmas N. 2008. GR24, a synthetic analog of strigolactones, stimulates the mitosis and growth of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Gigaspora rosea by boosting its energy metabolism. Plant Physiol 148:402–13. [CrossRef]

- Black B, Lee C, Horianopoulos LC, Jung WH, Kronstad JW. 2021. Respiring to infect: Emerging links between mitochondria, the electron transport chain, and fungal pathogenesis. PLoS Pathogens 17:e1009661. [CrossRef]

- Boddy, L. 1999. Saprotrophic cord-forming fungi: meeting the challenge of heterogeneous environments. Mycologia 91:13–32. [CrossRef]

- Boenisch MJ, Broz KL, Purvine SO, Chrisler WB, Nicora CD, Connolly LR, Freitag M, Baker SE, Kistler HC. 2017. Structural reorganization of the fungal endoplasmic reticulum upon induction of mycotoxin biosynthesis. Sci Rep 7:44296. [CrossRef]

- Bowman BJ, Draskovic M, Freitag M, Bowman EJ. 2009. Structure and distribution of organelles and cellular location of calcium transporters in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot Cell 8:1845–55. [CrossRef]

- Bowman BJ, Draskovic M, Schnittker RR, El-Mellouki T, Plamann MD, Sánchez-León E, Riquelme M, Bowman EJ. 2015. Characterization of a novel prevacuolar compartment in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot Cell 14:1253–63. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, BJ. 2023. The structure of prevacuolar compartments in Neurospora crassa as observed with super-resolution microscopy. PLOS One18:e0282989. [CrossRef]

- Brownlee C, Jennings DH. 1982. Long distance translocation in Serpula lacrimans: velocity estimates and the continuous monitoring of induced perturbations. Trans Brit Mycol Soc 79:143–8. [CrossRef]

- Butt TM, Hoch HC, Staples RC, Leger RYS. 1989. Use of Fluorochromes in the Study of Fungal Cytology and Differentiation. Exp Mycol 13:303–313. [CrossRef]

- Cairney JWG. 1992. Translocation of solutes in ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic rhizomorphs. Mycol Res 96:135–141. [CrossRef]

- Chang AL, Doering TL. 2018. Maintenance of mitochondrial morphology in Cryptococcus neoformans is critical for stress resistance and virulence. MBio 9:10–128. [CrossRef]

- Chatre L, Ricchetti M. 2014. Are mitochondria the Achilles’ heel of the Kingdom Fungi?. Curr Opin Microbiol Aug 20:49–54. [CrossRef]

- Cheema JY, He J, Wei W, Fu C. 2021. The endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria encounter structure and its regulatory proteins. Contact 4:25152564211064491. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Wei X, Liu GL, Hu Z, Chi ZM, Chi Z. 2020. Glycerol, trehalose and vacuoles had relations to pullulan synthesis and osmotic tolerance by the whole genome duplicated strain Aureobasidium melanogenum TN3-1 isolated from natural honey. Int J Biol Macromol 165:131–40. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Liu J, Fan Y, Xiang M, Kang S, Wei D. and Liu X. 2022. SNARE protein DdVam7 of the nematode-trapping fungus Drechslerella dactyloides regulates vegetative growth, conidiation, and the predatory process via vacuole assembly. Microbiol Spectr 10:e01872–22. [CrossRef]

- Cole L, Hyde GJ, Ashford AE. 1997. Uptake and compartmentalisation of fluorescent probes by Pisolithus tinctorius hyphae: evidence for an anion transport mechanism at the tonoplast but not for fluid-phase endocytosis. Protoplasma 199:18–29. [CrossRef]

- Cole L, Orlovich DA and Ashford AF. 1998. Structure, function, and motility of vacuoles in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet Biol 24:86–100. [CrossRef]

- Cole L, Davies D, Hyde GJ, Ashford AE. 2000a. ER-Tracker dye and BODIPY-brefeldin A differentiate the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi bodies from the tubular-vacuole system in living hyphae of Pisolithus tinctorius. J Microsc 197:239–49. [CrossRef]

- Cole L, Davies D, Hyde GJ, Ashford AE. 2000b. Brefeldin A affects growth, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi bodies, tubular vacuole system, and secretory pathway in Pisolithus tinctorius. Fungal Genet Biol 29:95–106. [CrossRef]

- Cox G, Moran KJ, Sanders F, Nockolds C, Tinker PB. 1980. Translocation and transfer of nutrients in vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizas. III. Polyphosphate granules and phosphorus translocation. New Phytol 84:649–659. [CrossRef]

- Darrah PR, Tlalka M, Ashford A, Watkinson SC, Fricker MD. 2006. The vacuole system is a significant intracellular pathway for longitudinal solute transport in basidiomycete fungi. Eukaryot Cell 5:1111–25. [CrossRef]

- Day KJ, Casler JC, Glick BS. 2018. Budding yeast has a minimal endomembrane system. Developmental Cell 44:56–72. [CrossRef]

- Dornan LG, Simpson JC. 2023. Rab6-mediated retrograde trafficking from the Golgi: the trouble with tubules. Small GTPases 14:26–44. [CrossRef]

- Faoro F, Faccio A, Balestrini R. 2022. Contributions of ultrastructural studies to the knowledge of filamentous fungi biology and fungi-plant interactions. Front Fungal Biol 2:805739. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Abalos JM, Fox H, Pitt C, Wells B, Doonan JH. 1998. Plant – adapted green fluorescent protein is a versatile vital reporter for gene expression, protein localization and mitosis in the filamentous fungus, Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol 27:121–30. [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Parton S, Parton RM, Hickey PC, Dijksterhuis J, Atkinson HA, Read ND. 2000. Confocal microscopy of FM4-64 as a tool for analysing endocytosis and vesicle trafficking in living fungal hyphae. J Microsc 198:246e259. [CrossRef]

- Fricker MD, Lee JA, Bebber DP, Tlalka M, Hynes J, Darrah PR, Watkinson SC, Boddy L. 2008. Imaging complex nutrient dynamics in mycelial networks. J Microsc 231:317–31. [CrossRef]

- Funamoto R, Saito K, Oyaizu H, Aono T, Saito M. 2015. pH measurement of tubular vacuoles of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus, Gigaspora margarita. Mycorrhiza 25:55–60. [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Bazán V, Pardo JP, Aguirre J. 2020. DnmA and FisA mediate mitochondria and peroxisome fission, and regulate mitochondrial function, ROS production and development in Aspergillus nidulans. Front Microbiol 11:837. [CrossRef]

- Gear, AR. 1974. Rhodamine 6G: a potent inhibitor of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 249:3628–37. [CrossRef]

- Gibeaux R, Hoepfner D, Schlatter I, Antony C, Philippsen P. 2013. Organization of organelles within hyphae of Ashbya gossypii revealed by electron tomography. Eukaryotic Cell 12:1423–32. [CrossRef]

- Girbardt, M. 1955. Lebendbeobachtungen an Polystictus versicolor (L). Flora 142:540–563.

- Gokbayrak ZD, Patel D, Brett CL. 2022. Acetate and hypertonic stress stimulate vacuole membrane fission using distinct mechanisms. Plos One 17:e0271199. [CrossRef]

- Granlund HI, Jennings DH, Thompson W. 1985. Translocation of solutes along rhizomorphs of Armillaria mellea. Trans Br Mycol Soc 84:111–119. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, DH. 1994. Fungal Physiology. 2nd edn. Wiley-Liss, New York. p.

- Groth A, Ahlmann S, Werner A, Pöggeler S. 2022. The vacuolar morphology protein VAC14 plays an important role in sexual development in the filamentous ascomycete Sordaria macrospora. Curr Genet 68:407–27. [CrossRef]

- Groth A, Schmitt K, Valerius O, Herzog B, Pöggeler S. 2021. Analysis of the putative nucleoporin POM33 in the filamentous fungus Sordaria macrospora. J Fungi 7:682. [CrossRef]

- Guilliermond, A. 1911. Sur les mitochondries des cellules végétales. Compt Rend Acad Sci 153:199–201.

- Guilliermond, A. 1941. The cytoplasm of the plant cell. Chronica Botanica Co. Waltham, Mass. USA. p. 247.

- Hatch, WR. 1935. Gametogenesis in Allomyces arbuscula. Ann Bot 49:623–649.

- Hawley ES, Wagner RP. 1967. Synchronous mitochondrial division in Neurospora crassa. J Cell Biol 35:489–99. [CrossRef]

- Heath I, Steinberg G. 1999. Mechanisms of hyphal tip growth: tube dwelling amebae revisited. Fungal Genet Biol 28:79–93. [CrossRef]

- Herman KC, Bleichrodt R. 2022. Go with the flow: mechanisms driving water transport during vegetative growth and fruiting. Fungal Biol Rev 41:10–23. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sánchez F, Peraza-Reyes L. 2022. Spatiotemporal dynamic regulation of organelles during meiotic development, insights from fungi. Front Cell Dev Biol 10:886710. [CrossRef]

- Hickey PC, Swift SR, Roca MG, Read ND. 2004. Live-cell imaging of filamentous fungi using vital fluorescent dyes and confocal microscopy. Methods Microbiol 34:63–87. [CrossRef]

- Hickey PC, Read ND. 2009. Imaging living cells of Aspergillus in vitro. Med Mycol 47:S110–9. [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, Y. 2021. Membrane traffic in Aspergillus oryzae and related filamentous fungi. J Fungi 7:534. [CrossRef]

- Hinze C, Boucrot E. 2018. Local actin polymerization during endocytic carrier formation. Biochem Soc Trans 46:565–576. [CrossRef]

- Honda SI, Hongladarom T, Wildman SG. 1964. Characteristic movements of organelles in streaming cytoplasm of plant cells, p. 485-502. In Allen RD, Kamlya N. [ed.], Primitive motile systems in cell biology. Academic Press, New York.

- Hyde GJ, Ashford AE. 1997. Vacuole motility and tubule-forming activity in Pisolithus tinctorius hyphae are modified by environmental conditions. Protoplasma 198:85–92. [CrossRef]

- Hyde GJ, Davies D, Perasso L, Cole L, Ashford AE. 1999. Microtubules, but not actin microfilaments, regulate vacuole motility and morphology in hyphae of Pisolithus tinctorius. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 42:114–124. [CrossRef]

- Hyde GJ, Davies D, Cole L, Ashford AE. 2002. Regulators of GTP-binding proteins cause morphological changes in the vacuole system of the filamentous fungus, Pisolithus tinctorius. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 51:133–46. [CrossRef]

- Inselman AL, Gathman AC, Lilly WW. 1999. Two fluorescent markers identify the vacuolar system of Schizophyllum commune. Curr Microbiol 38:295–9. [CrossRef]

- Jagernath JS, Meng S, Qiu J, Shi H, Kou Y. 2020. Selective degradation of mitochondria by mitophagy in pathogenic fungi. Am J Mol Biol 11:15–27. [CrossRef]

- Jazwinski, SM. 2004. Mitochondria, metabolism, and aging in yeast. Topics in Current Genetics: Model Systems in Aging. Eds Nystrőm T, Osiewacz HD. Berlin; Heidelberg; N.Y.: Springer-Verlag. p. 39–55. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, DH. 1987. The translocation of solutes in fungi. Biol Rev 62:215–143. [CrossRef]

- Kawano S, Tamura Y, Kojima R, Bala S, Asai E, Michel AH, Kornmann B, Riezman I, Riezman H, Sakae Y et al. 2018. Structure-function insights into direct lipid transfer between membranes by Mmm1-Mdm12 of ERMES. J Cell Biol 217:959–974. [CrossRef]

- Kilaru S, Schuster M, Ma W, Steinberg G. 2017. Fluorescent markers of various organelles in the wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. Fungal Genet Biol 105:16–27. [CrossRef]

- Kimura S, Maruyama JI, Watanabe T, Ito Y, Arioka M, Kitamoto K. 2010. In vivo imaging of endoplasmic reticulum and distribution of mutant α-amylase in Aspergillus oryzae. Fungal Genet Biol 47:1044–54. [CrossRef]

- Koch B, Traven A. 2019. Mitochondrial control of fungal cell walls: models and relevance in fungal pathogens. In Latgé JP. (eds) The Fungal Cell Wall. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 425. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Kornmann B, Currie E, Collins SR, Schuldiner M, Nunnari J, Weissman JS, Walter P. 2009. An ER-mitochondria tethering complex revealed by a synthetic biology screen. Science 325:477–481. [CrossRef]

- Lew, RR. 2019. Biomechanics of hyphal growth. In: Hoffmeister, D., Gressler, M. (eds) Biology of the Fungal Cell. The Mycota, Springer, Cham. 8:83–94. [CrossRef]

- Lilje O, Lilje E. Comparative imaging of the vacuolar reticulum of Saprolegnia ferax. 2006. In Imaging, Manipulation, and Analysis of Biomolecules, Cells, and Tissues IV 6088:401–411 SPIE. USA. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Zhang J, Yan H, Yi T, Shim WB, Zhou Z. 2024. FvVam6 is associated with fungal development and fumonisin biosynthesis via vacuole morphology regulation in Fusarium verticillioides. J Integr Agric In Press. [CrossRef]

- Lu, BC. 2006. Programmed cell death in fungi. The Mycota I: Growth, Differentiation and Sexuality. Eds Kües U, Fischer R. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. p. 167–187. [CrossRef]

- Marchetti A, Lelong E, Cosson P. 2009. A measure of endosomal pH by flow cytometry in Dictyostelium. BMC Res Notes 2:7. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Andrade JM, Roberson RW, Riquelme M. 2024. A bird’s-eye view of the endoplasmic reticulum in filamentous fungi. MMBR 88:e00027–23. [CrossRef]

- Maruyama JI, Kikuchi S, Kitamoto K. 2006. Differential distribution of the endoplasmic reticulum network as visualized by the BipA–EGFP fusion protein in hyphal compartments across the septum of the filamentous fungus, Aspergillus oryzae. Fungal Genet Biol 43:642–54. [CrossRef]

- Maruyama JI, Kitamoto K. 2007. Differential distribution of the endoplasmic reticulum network in filamentous fungi. FEMS Microbiol Lett 272:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Matrosova EV, Masheyka IS, Kudryavtseva OA, Kamzolkina OV. 2009. Mitochondrial morphogenesis and ultrastructure of basidiomycetes from genera Agaricus and Pleurotus. Cell Tiss Biol 3:369–380. [CrossRef]

- Mazheika I, Voronko O, Kudryavtseva O, Novoselova D, Pozdnyakov L, Mukhin V, Kolomiets O, Kamzolkina O. 2020. Nitrogen-obtaining and -conserving strategies in xylotrophic basidiomycetes. Mycologia 112:455–473. [CrossRef]

- Mazheika IS, Psurtseva NV, Kamzolkina OV. 2022. Lomasomes and other fungal plasma membrane macroinvaginations have a tubular and lamellar genesis. J Fungi 8:1316. [CrossRef]

- Mazheika IS, Kamzolkina OV. 2025. The curtain model as an alternative and complementary to the classic turgor concept of filamentous fungi. Archiv Microbiol 207:65. [CrossRef]

- Mileykovskaya E, Dowhan W, Birke RL, Zheng D, Lutterodt L, Haines TH. 2001. Cardiolipin binds nonyl acridine orange by aggregating the dye at exposed hydrophobic domains on bilayer surfaces. FEBS Lett 507:187–90. [CrossRef]

- Money, NP. 2025. Physical forces supporting hyphal growth. Fungal Genet Biol 177:103961. [CrossRef]

- Moore RT, McAlear JH. 1963. Fine structure of mycota: 9. Fungal mitochondria. J Ultrastruct Res 8:144–53. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Gómez SA, Slamovits CH, Dacks JB, Baier KA, Spencer KD, Wideman JG. 2015. Ancient homology of the mitochondrial contact site and cristae organizing system points to an endosymbiotic origin of mitochondrial cristae. Curr Biol 25:1489–95. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Espíndola R, Suaste-Olmos F, Peraza-Reyes L. 2020. Dynamic regulation of peroxisomes and mitochondria during fungal development. J Fungi 6:302. [CrossRef]

- Oettmeier C, Döbereiner HG. 2019. Mitochondrial numbers increase during glucose deprivation in the slime mold Physarum polycephalum. Protoplasma 256:1647–55. [CrossRef]

- Ohneda M, Arioka M, Nakajima H, Kitamoto K. 2002. Visualization of vacuoles in Aspergillus oryzae by expression of CPY–EGFP. Fungal Genet Biol 37:29–38. [CrossRef]

- Ohsumi K, Arioka M, Nakajima H, Kitamoto K. 2002. Cloning and characterization of a gene (avaA) from Aspergillus nidulans encoding a small GTPase involved in vacuolar biogenesis. Gene 291:77e84. [CrossRef]

- Oka M, Maruyama J, Arioka M, Nakajima H, Kitamoto K. 2004. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of avaB, a gene encoding Vam6p/Vps39p-like protein in Aspergillus nidulans. FEMS Microbiol Lett 232:113e121. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto K, Shaw JM. 2005. Mitochondrial morphology and dynamics in yeast and multicellular eukaryotes. Annu Rev Genet 39:503–36. [CrossRef]

- Olsson S, Gray SN. 1998. Patterns and dynamics of 32P-phosphate and labelled 2-aminoisobutyric acid (14C-AIB) translocation in intact basidiomycete mycelia. FEMS Microbiol Ecology 26:109–120. [CrossRef]

- Orlovich DA, Ashford AE. 1993. Polyphosphate granules are an artefact of specimen preparation in the ecto-mycorrhizal fungus Pisolithus tinctorius. Protoplasma 173:91–105. [CrossRef]

- Osiewacz HD, Bernhardt D. 2013. Mitochondrial quality control: impact on aging and life span-a mini-review. Gerontology 59:413–20. [CrossRef]

- Peñalva MA, Zhang J, Xiang X and Pantazopoulou A. 2017. Transport of fungal RAB11 secretory vesicles involves myosin-5, dynein/dynactin/p25, and kinesin-1 and is independent of kinesin-3. Mol Biol Cell 28:947–961. [CrossRef]

- Perry SW, Norman JP, Barbieri J, Brown EB, Gelbard HA. 2011. Mitochondrial membrane potential probes and the proton gradient: a practical usage guide. BioTechniques 50:98–115. [CrossRef]

- Potapova TV, Boitzova LY, Golyshev SA, Popinako AV. 2014. The organization of mitochondria in growing hyphae of Neurospora crassa. Cell Tiss Biol 8:166–74. [CrossRef]

- Rees B, Shepherd VA, Ashford AE. 1994. Presence of a motile tubular vacuole system in different phyla of fungi. Mycol Res 98:985–92. [CrossRef]

- Reynaga-Peña CG, Bartnicki-García S. 2005. Cytoplasmic contractions in growing fungal hyphae and their morphogenetic consequences. Arch Microbiol 183:292–300. [CrossRef]

- Richards A, Veses V, Gow NA. 2010. Vacuole dynamics in fungi. Fungal Biol Rev 24:93–105. [CrossRef]

- Richards A, Gow NA, Veses V. 2012. Identification of vacuole defects in fungi. J Microbiol Methods 91:155–63. [CrossRef]

- Roberson RW, Fuller MS. 1988. Ultrastructural aspects of the hyphal tip of Sclerotium rolfsii preserved by freeze substitution. Protoplasma 146:143–149. [CrossRef]

- Roberson RW, Abril M, Blackwell M, Letcher P, McLaughlin DJ, Mouriño-Pérez RR, Riquelme M, Uchida M. 2010. Hyphal structure. In Cellular and molecular biology of filamentous fungi. Eds. Borkovich KA, Ebbole DJ. ASM Press, Washington, DC. 8–24. [CrossRef]

- Rossanese OW, Soderholm J, Bevis BJ, Sears IB, O’Connor J, Williamson EK, Glick BS. 1999. Golgi structure correlates with transitional endoplasmic reticulum organization in Pichia pastoris and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 145:69–81. [CrossRef]

- Rost FW, Shepherd VA, Ashford AE. 1995. Estimation of vacuolar pH in actively growing hyphae of the fungus Pisolithus tinctorius. Mycol Res 99:549–53. [CrossRef]

- Saito K, Kuga-Uetake Y, Saito M, Peterson RL. 2006. Vacuolar localization of phosphorus in hyphae of Phialocephala fortinii, a dark septate fungal root endophyte. Can J Microbiol 52:643–50. [CrossRef]

- Scheckhuber CQ, Erjavec N, Tinazli A, Hamann A, Nyström T, Osiewacz HD. 2007. Reducing mitochondrial fission results in increased life span and fitness of two fungal ageing models. Nat Cell Biol 9:99–105. [CrossRef]

- Scheckhuber CQ, Brust D, Osiewacz HD. 2012. Cellular homeostasis in fungi: impact on the aging process. Subcell Biochem 57:233–250. [CrossRef]

- Scheckhuber, CQ. 2015. Penicillium chrysogenum, 1: system for studying cellular effects of methylglyoxal. BMC Microbiol 15. [CrossRef]

- Schmieder SS, Stanley CE, Rzepiela A, van Swaay D, Sabotič J, Nørrelykke SF, deMello AJ, Aebi M, Künzler M. 2019. Bidirectional propagation of signals and nutrients in fungal networks via specialized hyphae. Curr Biol 29:217–28. [CrossRef]

- Schuster M, Kilaru S, Wösten HAB, Steinberg G. 2025. Secretion and endocytosis in subapical cells support hyphal tip growth in the fungus Trichoderma reesei. Nat Commun 16:4402. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd VA, Orlovich DA, Ashford AE. 1993a. A dynamic continuum of pleiomorphic tubules and vacuoles in growing hyphae of a fungus. J Cell Sci 104:495–507. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd VA, Orlovich DA, Ashford AE. 1993b. Cell-to-cell transport via motile tubules in growing hyphae of a fungus. J Cell Sci 105:1173–8. [CrossRef]

- Shoji JY, Arioka M, Kitamoto K. 2006a. Possible involvement of pleiomorphic vacuolar networks in nutrient recycling in filamentous fungi. Autophagy 2:226–7. [CrossRef]

- Shoji JY, Arioka M, Kitamoto K. 2006b. Vacuolar membrane dynamics in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Eukaryot Cell 5:411–21. [CrossRef]

- Shoji JY, Craven KD. 2011. Autophagy in basal hyphal compartments: A green strategy of great recyclers. Fungal Biol Rev 25:79–83. [CrossRef]

- Shoji JY, Kikuma T, Kitamoto K. 2014. Vesicle trafficking, organelle functions, and unconventional secretion in fungal physiology and pathogenicity. Curr Opin Microbiol 20:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Skulachev, VP. 2001. Mitochondrial filaments and clusters as intracellular power-transmitting cables. Trends Biochem Sci 26:23–9. [CrossRef]

- Stodulkova E, Císařová I, Kolařík M, Chudíčková M, Novak P, Man P, Kuzma M, Pavlů B, Černý J, Flieger M. 2015. Biologically active metabolites produced by the basidiomycete Quambalaria cyanescens. PLoS One 10:e0118913. [CrossRef]

- Smith SE, Read DJ. 1997. Mycorrhizal symbiosis, 2nd edn. London, UK: Academic Press.

- Steinberg G, Penalva MA, Riquelme M, Wosten HA, Harris SD. 2017. Cell biology of hyphal growth. Microbiol Spectr 5:1–34. [CrossRef]

- Stradalova V, Blazikova M, Grossmann G, Opekarová M, Tanner W, Malinsky J. 2012. Distribution of cortical endoplasmic reticulum determines positioning of endocytic events in yeast plasma membrane. PloS One 7:e35132. [CrossRef]

- Suelmann R, Fischer R. 2000. Mitochondrial movement and morphology depend on an intact actin cytoskeleton in Aspergillus nidulans. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 45:42–50. [CrossRef]

- Takei K, McPherson PS, Schmid SL, Camilli PD. 1995. Tubular membrane invaginations coated by dynamin rings are induced by GTP-γ S in nerve terminals. Nature 374:186–190. [CrossRef]

- Takeshita N, Manck R, Grün N, de Vega SH and Fischer R. 2014. Interdependence of the actin and the microtubule cytoskeleton during fungal growth. Curr Opin Microb 20:34–41. [CrossRef]

- Takeshita N, Evangelinos M, Zhou L, Serizawa T, Somera-Fajardo RA, Lu L, Takayab N, Nienhaus GU, Fischer R. 2017. Pulses of Ca2+ coordinate actin assembly and exocytosis for stepwise cell extension. PNAS 114:5701–5706. [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, N. 2019. Control of actin and calcium for chitin synthase delivery to the hyphal tip of Aspergillus. In: Latgé, JP. (eds) The Fungal Cell Wall. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Springer, Cham. 425. [CrossRef]

- Tarutani Y, Ohsumi K, Arioka M, Nakajima H, Kitamoto K. 2001. Cloning and characterization of Aspergillus nidulans vpsA gene which is involved in vacuolar biogenesis. Gene 268:23e30. [CrossRef]

- Thompson W, Eamus D, Jennings DH. 1985. Water flux through mycelium of Serpula lacrimans. Trans Brit Mycol Soc 84:601–8. [CrossRef]

- Timonen S, Finlay RD, Olsson S, Söderström B. 1996. Dynamics of phosphorus translocation in intact ectomycorrhizal systems: non-destructive monitoring using a ß-scanner. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 19:171–180. [CrossRef]

- Tlalka M, Hensman D, Darrah PR, Watkinson SC, Fricker MD. 2003. Noncircadian oscillations in amino acid transport have complementary profiles in assimilatory and foraging hyphae of Phanerochaete velutina. New Phytol 158:325–35. [CrossRef]

- Tlalka M, Bebber DP, Darrah PR, Watkinson SC, Fricker MD. 2008. Quantifying dynamic resource allocation illuminates foraging strategy in Phanerochaete velutina. Fungal Genet Biol 45:1111–1121. [CrossRef]

- Tuszynska S, Davies D, Turnau K, Ashford AE. 2006. Changes in vacuolar and mitochondrial motility and tubularity in response to zinc in a Paxillus involutus isolate from a zinc-rich soil. Fungal Gen Biol 43:155–63. [CrossRef]

- Tuszyńska, S. 2006. Ni2+ induces changes in the morphology of vacuoles, mitochondria and microtubules in Paxillus involutus cells. New Phytologist 169:819–28. [CrossRef]

- Uetake Y, Kojima T, Ezawa T, Saito M. 2002. Extensive tubular vacuole system in an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus, Gigaspora margarita. New Phytologist 154:761–8. [CrossRef]

- Venables CE, Watkinson SC. 1989. Medium-induced changes in patterns of free and combined amino acids in mycelium of Serpula lacrymans. J General Microbiol 135:1369–1374. [CrossRef]

- Verma S, Shakya VP, Idnurm A. 2018. Exploring and exploiting the connection between mitochondria and the virulence of human pathogenic fungi. Virulence 9:426–46. [CrossRef]

- Veses V, Richards A, Gow NA. 2008. Vacuoles and fungal biology. Curr Opin Microbiol 11:503–10. [CrossRef]

- Voelz K, Johnston SA, Smith LM, Hall RA, Idnurm A, May RC. 2014. ‘Division of labour’in response to host oxidative burst drives a fatal Cryptococcus gattii outbreak. Nat Comm 5:5194. [CrossRef]

- Walter A, Erdmann S, Bocklitz T, Jung EM, Vogler N, Akimov D, Dietzek B, Rösch P, Kothe E, Popp J. 2010. Analysis of the cytochrome distribution via linear and nonlinear Raman spectroscopy. Analyst 135:908–17. [CrossRef]

- Watkinson SC, Boddy L, Burton K, Darrah PR, Eastwood D, Fricker MD, Tlalka M. 2005. New approaches to investigating the function of mycelial networks. Mycologist 19:11–7. [CrossRef]

- Weber RW, Wakley GE, Pitt D. 1998. Histochemical and ultrastructural characterization of fungal mitochondria. Mycologist 12:174–9. [CrossRef]

- Weber RW, Wakley GE, Thines E, Talbot NJ. 2001. The vacuole as central element of the lytic system and sink for lipid droplets in maturing appressoria of Magnaporthe grisea. Protoplasma 216:101–12. [CrossRef]

- Weber, RW. 2002. Vacuoles and the fungal lifestyle. Mycologist 16:10–20. [CrossRef]

- Wedlich-Soldner R, Schulz I, Straube A, Steinberg G. 2002. Dynein supports motility of endoplasmic reticulum in the fungus Ustilago maydis. Mol Biol Cell 13:965–77. [CrossRef]

- West M, Zurek N, Hoenger A, Voeltz GK. 2011. A 3D analysis of yeast ER structure reveals how ER domains are organized by membrane curvature. J Cell Biol 193:333–46. [CrossRef]

- Westermann, B. 2010. Mitochondrial dynamics in model organisms: what yeasts, worms and flies have taught us about fusion and fission of mitochondria. Semin Cell Dev Biol 21:542–9.

- Wright R, Basson M, D’Ari L, Rine J. 1988. Increased amounts of HMG-CoA reductase induce “karmellae”: a proliferation of stacked membrane pairs surrounding the yeast nucleus. J Cell Biol 107:101–114. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang X, Tlalka M, Davies DS, Allaway WG, Watkinson SC, Ashford AE. 2009. Spitzenkörper, vacuoles, ring-like structures, and mitochondria of Phanerochaete velutina hyphal tips visualized with carboxy-DFFDA, CMAC and DiOC6 (3). Mycol Res 113:417–31. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).