Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

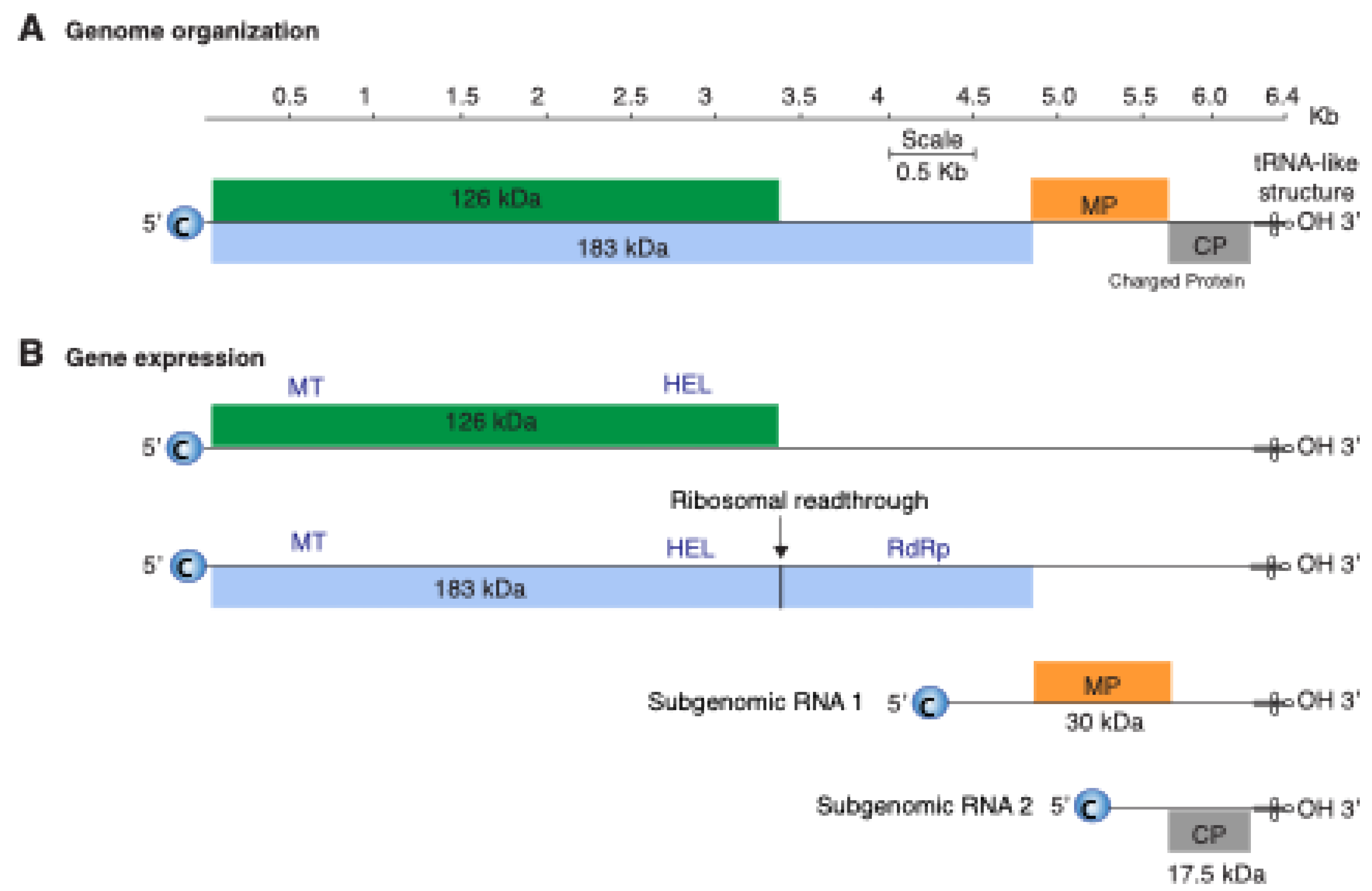

The genus Tobamovirus belongs to the family Virgaviridae, and the genome consists of monopartite, positive, single-strand RNA. Most species have four open reading frames encoding four essential proteins. Transmission occurs by mechanical contact between plants and sometimes by seed. Tobamovirus fructirugosum (Tomato brown rugose fruit virus, ToBRFV) is the most recent species in the genus, was first reported in 2015, broke genetic resistance that had been effective in tomato for sixty years, has caused devastating damage to tomato production worldwide, and highlights the importance of understanding genomic variation and evolution of tobamoviruses. In this study, we measured and characterized nucleotide variation for the entire genome and for all species in the genus Tobamovirus and measured the selection pressure acting on each open reading frame. Results showed that low nucleotide diversity and negative selection pressure are general features of tobamoviruses, with values that are approximately the same across open reading frames and without hypervariable areas. A comparison of nucleotide diversity between T. fructirugosum and its close relatives, T. tomatotessellati (Tomato mosaic virus, ToMV) and T. tabaci (Tobacco mosaic virus, TMV), showed low nucleotide diversity in the movement protein region harboring the resistance-breaking mutation. Furthermore, phylogenetic and diversity analyses showed that T. fructirugosum continues to evolve, and geographical distribution and host influence genomic diversity.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tobamovirus Genomic Sequences

| Scheme 1. | Virus name | ICTV Abbreviation | No. of accessions | Reference genome1 | Length (nt) | 95% length | Accessions (≥ 95%)3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. maculacapsici | Bell pepper mottle virus | BPMV | 5 | NC 009642.1 | 6375 | 6056 | 4 |

| T. brugmansiae | Brugmansia mild mottle virus | BrMMV | 2 | NC 010944.1 | 6381 | 6062 | 2 |

| T. cacti | Cactus mild mottle virus | CMMoV | 5 | NC 011803.1 | 6449 | 6127 | 3 |

| NA2 | Cactus tobamovirus 1 | 2 | MW938767.1 | 6458 | 6135 | 2 | |

| NA2 | Cactus tobamovirus 2 | 2 | MW938766.1 | 6368 | 6050 | 2 | |

| NA2 | Chili pepper mild mottle virus | 14 | MN164455.1 | 6383 | 6064 | 2 | |

| T. clitoriae | Clitoria yellow mottle virus | CliYMV | 2 | NC 016519.1 | 6514 | 6188 | 2 |

| T. maculafructi | Cucumber fruit mottle mosaic virus | CFMMV | 19 | NC 002633.1 | 6562 | 6234 | 6 |

| T. viridimaculae | Cucumber green mottle mosaic virus | CGMMV | 484 | NC 001801.1 | 6424 | 6103 | 198 |

| T. cucumeris | Cucumber mottle virus | CMoV | 2 | NC 008614.1 | 6485 | 6161 | 2 |

| T. frangipani | Frangipani mosaic virus | FrMV | 9 | NC 014546.1 | 6643 | 6311 | 4 |

| T. fortpiercense | Hibiscus latent Fort Pierce virus | HLFPV | 26 | NC 025381.1 | 6431 | 6109 | 10 |

| T. singaporense | Hibiscus latent Singapore virus | HLSV | 9 | NC 008310.2 | 6485 | 6161 | 6 |

| NA2 | Hoya chlorotic spot virus | 2 | NC 034509.1 | 6386 | 6067 | 2 | |

| NA2 | Hoya necrotic spot virus | 4 | LC807720.1 | 6425 | 6104 | 3 | |

| T. kyuri | Kyuri green mottle mosaic virus | KGMMV | 51 | NC 003610.1 | 6514 | 6188 | 4 |

| T. maracujae | Maracuja mosaic virus | MarMV | 2 | NC 008716.1 | 6794 | 6454 | 2 |

| T. obudae | Obuda pepper virus | ObPV | 4 | NC 003852.1 | 6507 | 6182 | 4 |

| T. odontoglossi | Odontoglossum ringspot virus | ORSV | 241 | NC 001728.1 | 6618 | 6287 | 14 |

| NA2 | Opuntia virus 2 | 19 | NC 040685.2 | 6453 | 6130 | 8 | |

| T. paprikae | Paprika mild mottle virus | PaMMV | 19 | NC 004106.1 | 6524 | 6198 | 9 |

| T. passiflorae | Passion fruit mosaic virus | PFMV | 2 | NC 015552.1 | 6791 | 6451 | 2 |

| T. capsici | Pepper mild mottle virus | PMMoV | 662 | NC 003630.1 | 6357 | 6039 | 86 |

| NA2 | Piper chlorosis virus | 3 | ON924221.1 | 6237 | 5925 | 2 | |

| T. plumeriae | Plumeria mosaic virus | PluMV | 4 | NC 026816.1 | 6688 | 6354 | 4 |

| T. muricaudae | Rattail cactus necrosis-associated virus | RCNaV | 22 | NC 016442.1 | 6506 | 6181 | 5 |

| T. rehmanniae | Rehmannia mosaic virus | RheMV | 75 | NC 009041.1 | 6395 | 6075 | 8 |

| T. plantagonis | Ribgrass mosaic virus | RMV | 41 | NC 002792.2 | 6311 | 5995 | 11 |

| T. streptocarpi | Streptocarpus flower break virus | SFBV | 6 | NC 008365.1 | 6279 | 5965 | 5 |

| T. mititessellati | Tobacco mild green mosaic virus | TMGMV | 398 | NC 001556.1 | 6355 | 6037 | 40 |

| T. tabaci | Tobacco mosaic virus | TMV | 653 | NC 001367.1 | 6395 | 6075 | 111 |

| T. fructirugosum | Tomato brown rugose fruit virus | TBRFV | 451 | NC 028478.1 | 6393 | 6073 | 248 |

| T. tomatotessellati | Tomato mosaic virus | ToMV | 372 | NC 002692.1 | 6383 | 6064 | 81 |

| T. maculatessellati | Tomato mottle mosaic virus | ToMMV | 62 | NC 022230.1 | 6398 | 6078 | 28 |

| T. tropici | Tropical soda apple mosaic virus | TSAMV | 13 | NC 030229.1 | 6350 | 6033 | 11 |

| T. rapae | Turnip vein clearing virus | TVCV | 29 | NC 001873.1 | 6311 | 5995 | 12 |

| T. wasabi | Wasabi mottle virus | WMoV | 6 | NC 003355.1 | 6298 | 5983 | 6 |

| NA2 | Watermelon green mottle mosaic virus | WGMMV | 6 | MH837097.1 | 6482 | 6158 | 6 |

| T. anthocercis | Yellow tailflower mild mottle virus | YTMMV | 97 | NC 022801.1 | 6379 | 6060 | 4 |

| T. youcai | Youcai mosaic virus | YoMV | 129 | NC 004422.1 | 6303 | 5988 | 33 |

| T. cucurbitae | Zucchini green mottle mosaic virus | ZGMMV | 10 | NC 003878.1 | 6513 | 6187 | 5 |

2.2. Tobamovirus Phylogeny

2.3. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism and Nucleotide Diversity

2.4. Selection Analyses

2.5. Maximum Likelihood Phylogenetic Tree for T. fructirugosum

2.6. Multidimensional Scaling

3. Results

3.1. Tobamoviruses Group According to the Botanical Family of Their Host

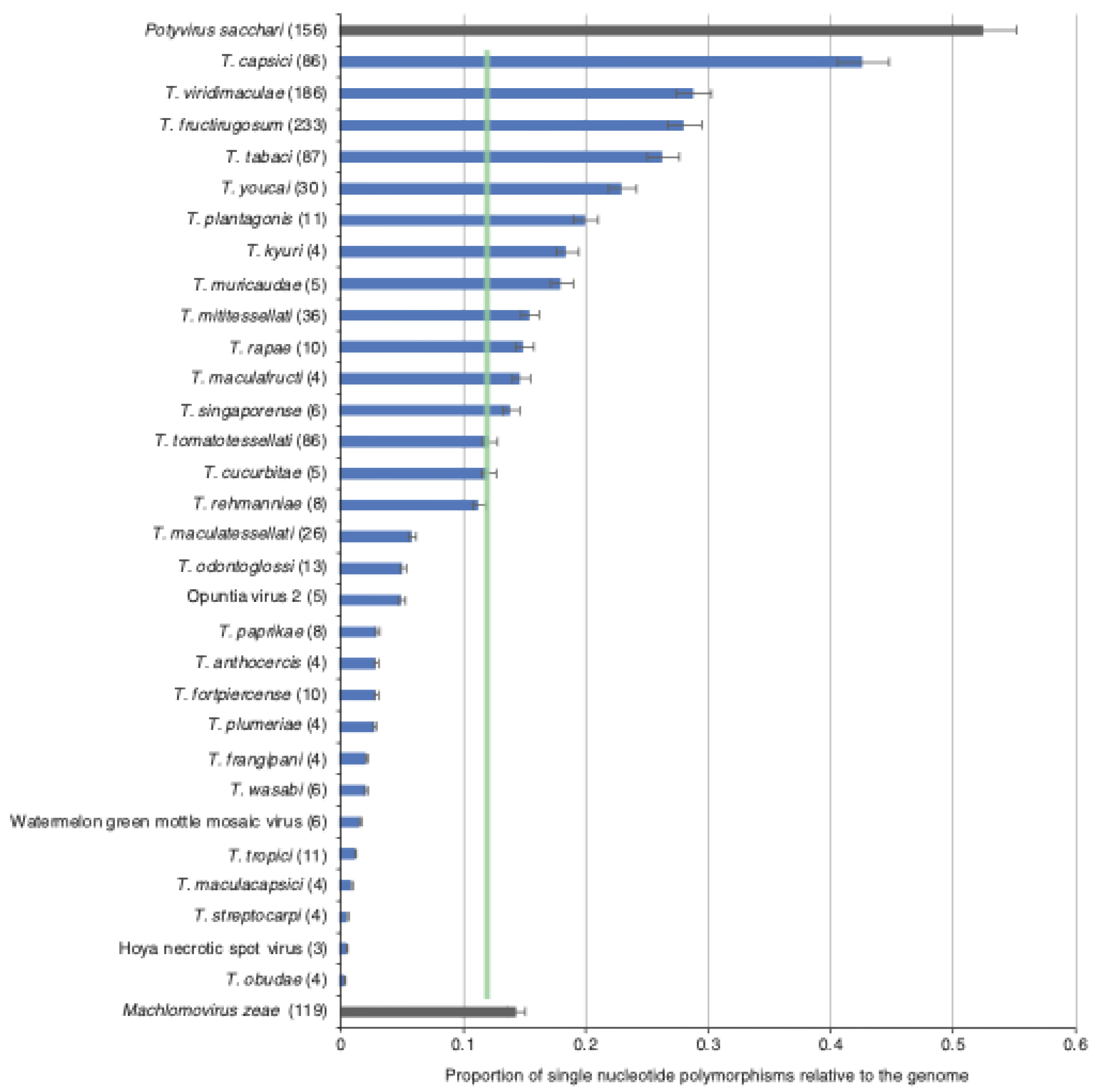

3.2. Tobamovirus Genome Diversity

3.3. Nucleotide Diversity by Open Reading Frame

3.4. Selection Analysis by Open Reading Frame

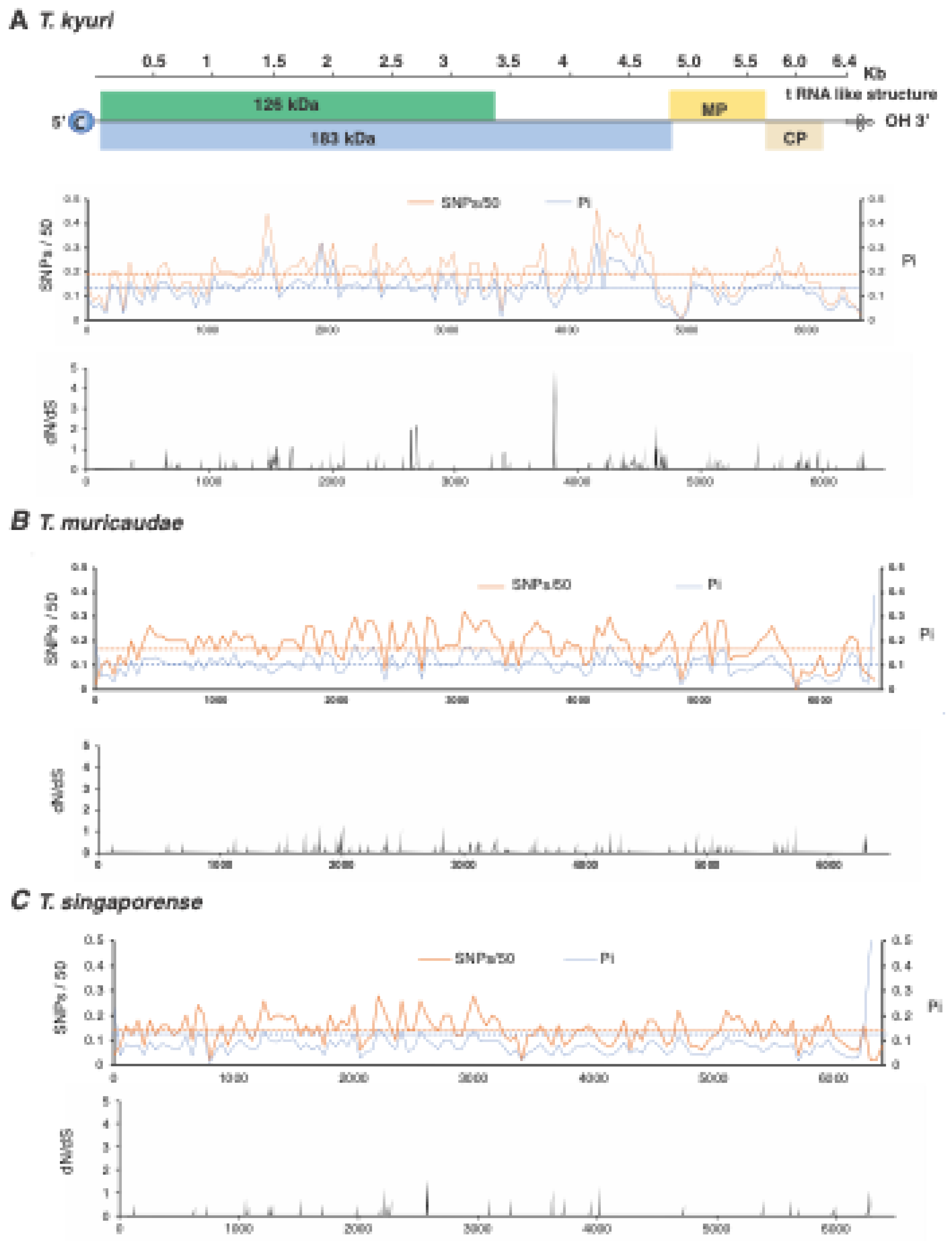

3.5. No Hypervariable Areas Were Detected in the Tobamovirus Genome

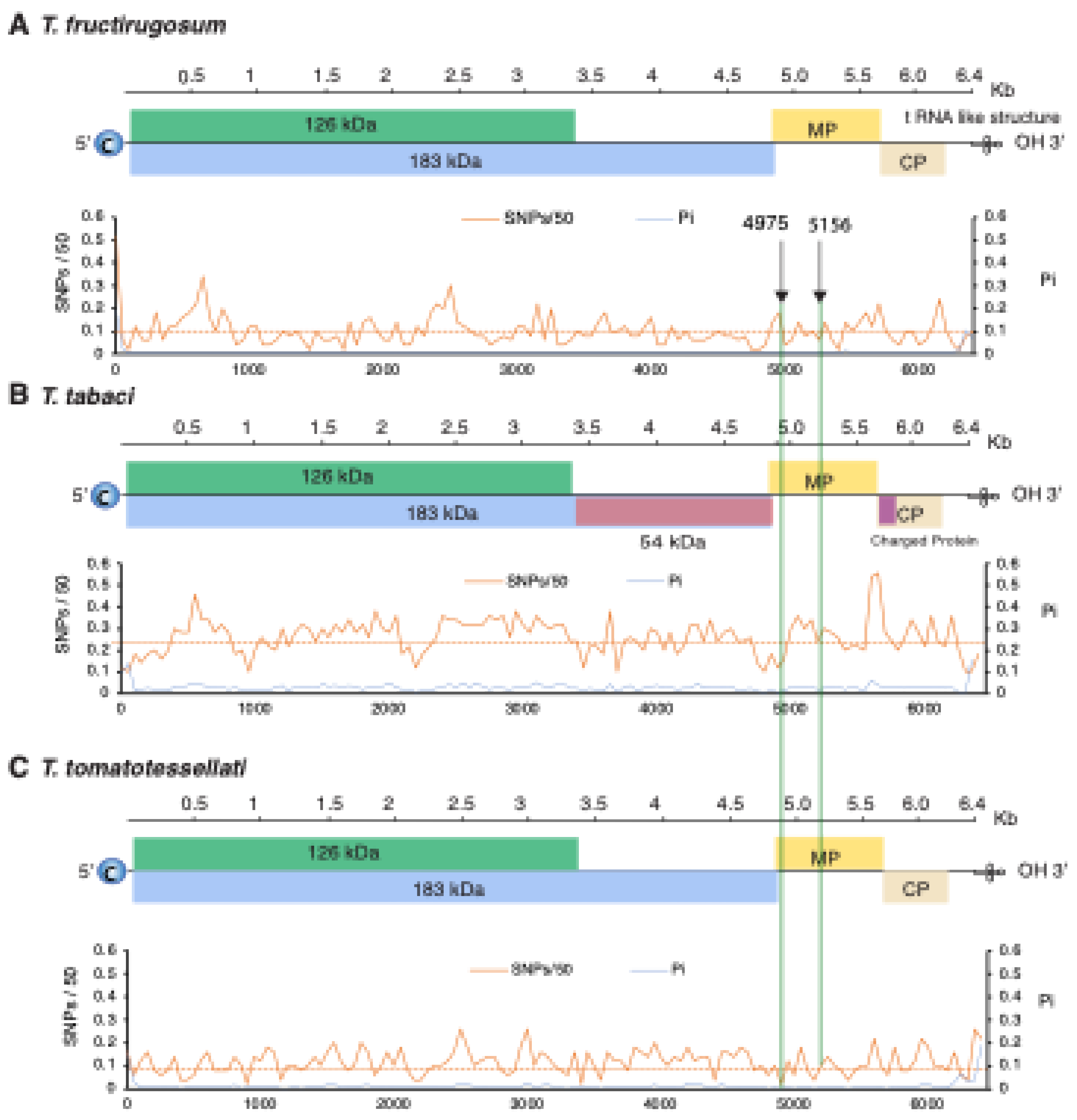

3.6. Variation in T. fructirugosum

3.7. Phylogenetic Analysis of T. fructirugosum

3.8. Geographical Distribution Correlates with Virus Variation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dorokhov, Y.L.; Sheshukova, E.V.; Komarova, T.V. , Tobamoviruses and their diversity. In Plant Viruses, CRC Press: 2018; pp 65-80.

- Spiegelman, Z.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P. , Breaking Boundaries: The Perpetual Interplay Between Tobamoviruses and Plant Immunity. 2024, 58, 24–24.

- Luria, N.; Smith, E.; Reingold, V.; Bekelman, I.; Lapidot, M.; Levin, I.; Elad, N.; Tam, Y.; Sela, N.; Abu-Ras, A. , A new Israeli Tobamovirus isolate infects tomato plants harboring Tm-22 resistance genes. PloS one 2017, 12, e0170429–e0170429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, N.; Mansour, A.; Ciuffo, M.; Falk, B.W.; Turina, M. , A new tobamovirus infecting tomato crops in Jordan. Archives of virology 2016, 161, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, J.P. , Engineered Resistance to Tobamoviruses. In Viruses, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI): 2024; Vol. 16.

- Dombrovsky, A.; Smith, E. , Seed Transmission of Tobamoviruses: Aspects of Global Disease Distribution. In Advances in Seed Biology, InTech: 2017.

- Darzi, E.; Smith, E.; Shargil, D.; Lachman, O.; Ganot, L.; Dombrovsky, A. , The honeybee Apis mellifera contributes to Cucumber green mottle mosaic virus spread via pollination. Plant Pathology 2018, 67, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Kusakari, S.-i.; Kawaratani, M.; Negoro, J.-I.; Ohki, S.T.; Osaki, T. , Tobacco mosaic virus is transmissible from tomato to tomato by pollinating bumblebees. Journal of General Plant Pathology 2000, 66, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, K.; Ishikawa, M. , Replication of tobamovirus RNA. Annual Review of Phytopathology 2016, 54, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahola, T.; Laakkonen, P.; Vihinen; Helena; Kääriäinen, L., Critical residues of Semliki Forest virus RNA capping enzyme involved in methyltransferase and guanylyltransferase-like activities. Journal of virology 1997, 71, 392–397. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahola, T.; den Boon, J.A.; Ahlquist, P. , Helicase and capping enzyme active site mutations in brome mosaic virus protein 1a cause defects in template recruitment, negative-strand RNA synthesis, and viral RNA capping. Journal of virology 2000, 74, 8803–8811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Laín, S.; García, J.A. , RNA helicase activity of the plum pox potyvirus CI protein expressed in Escherichia coli. Mapping of an RNA binding domain. Nucleic Acids Res 1995, 23, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goregaoker, S.P.; Culver, J.N. , Oligomerization and activity of the helicase domain of the tobacco mosaic virus 126- and 183-kilodalton replicase proteins. J Virol 2003, 77, 3549–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palukaitis, P.; Akbarimotlagh, M.; Astaraki, S.; Shams-Bakhsh, M.; Yoon, J.Y. , The Forgotten Tobamovirus Genes Encoding the 54 kDa Protein and the 4–6 kDa Proteins. In Viruses, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI): 2024; Vol. 16.

- Lewandowski, D.J.; Dawson, W.O. , Functions of the 126-and 183-kDa proteins of tobacco mosaic virus. Virology 2000, 271, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Vossenberg, B.T.L.H.; Dawood, T.; Woźny, M.; Botermans, M. , First Expansion of the Public Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus (ToBRFV) Nextstrain Build; Inclusion of New Genomic and Epidemiological Data. PhytoFrontiers™ 2021, 1, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, B.; Gilliard, A.; Jaiswal, N.; Ling, K.S. , Comparative Analysis of Host Range, Ability to Infect Tomato Cultivars with Tm-22 Gene, and Real-Time Reverse Transcription PCR Detection of Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus. Plant Disease 2021, 105, 3643–3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Griffiths, J.S.; Marchand, G.; Bernards, M.A.; Wang, A. , Tomato brown rugose fruit virus: An emerging and rapidly spreading plant RNA virus that threatens tomato production worldwide. Molecular Plant Pathology 2022, 23, 1262–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani, A. , Genetic analysis of tomato brown rugose fruit virus reveals evolutionary adaptation and codon usage bias patterns. Scientific Reports, 2024; 14. [Google Scholar]

- Zamfir, A.D.; Babalola, B.M.; Fraile, A.; McLeish, M.J.; García-Arenal, F. , Tobamoviruses Show Broad Host Ranges and Little Genetic Diversity Among Four Habitat Types of a Heterogeneous Ecosystem. Phytopathology 2023, 113, 1697–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maayan, Y.; Pandaranayaka, E.P.J.; Srivastava, D.A.; Lapidot, M.; Levin, I.; Dombrovsky, A.; Harel, A. , Using genomic analysis to identify tomato Tm-2 resistance-breaking mutations and their underlying evolutionary path in a new and emerging tobamovirus. Archives of Virology 2018, 163, 1863–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagán, I.; Firth, C.; Holmes, E.C. , Phylogenetic analysis reveals rapid evolutionary dynamics in the plant RNA virus genus tobamovirus. Journal of Molecular Evolution 2010, 71, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J.; Adkins, S.; Bragard, C.; Gilmer, D.; Li, D.; MacFarlane, S.A.; Wong, S.M.; Melcher, U.; Ratti, C.; Ryu, K.H.; Ictv Report, C. , ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Virgaviridae. J Gen Virol 2017, 98, 1999–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wan, Z.; Coarfa, C.; Drabek, R.; Chen, L.; Ostrowski, E.A.; Liu, Y.; Weinstock, G.M.; Wheeler, D.A.; Gibbs, R.A. , A SNP discovery method to assess variant allele probability from next-generation resequencing data. Genome research 2010, 20, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaTourrette, K.; Holste, N.M.; Garcia-Ruiz, H. , Polerovirus genomic variation. Virus Evolution 2021, 7, veab102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A., FigTree V1.4.3. In 2009.

- Nigam, D.; LaTourrette, K.; Souza, P.F.N.; Garcia-Ruiz, H. , Genome-Wide Variation in Potyviruses. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, A. , Using the confidence interval confidently. Journal of thoracic disease 2017, 9, 4125–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, D.; Garcia-Ruiz, H. , Variation Profile of the Orthotospovirus Genome. Pathogens 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korunes, K.L.; Samuk, K. , pixy: Unbiased estimation of nucleotide diversity and divergence in the presence of missing data. Molecular ecology resources 2021, 21, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delport, W.; Poon, A.F.; Frost, S.D.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L. , Datamonkey 2010: a suite of phylogenetic analysis tools for evolutionary biology. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2455–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murrell, B.; Wertheim, J.O.; Moola, S.; Weighill, T.; Scheffler, K.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L. , Detecting individual sites subject to episodic diversifying selection. PLoS genetics 2012, 8, e1002764–e1002764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryazhimskiy, S.; Plotkin, J.B. , The population genetics of dN/dS. PLoS Genet 2008, 4, e1000304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugal, C.F.; Wolf, J.B.W.; Kaj, I. , Why Time Matters: Codon Evolution and the Temporal Dynamics of dN/dS. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2013, 31, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. , IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Molecular biology and evolution 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A. , MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 1998, 14, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, J.B. , Multidimensional scaling. Murry Hill 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Braidwood, L.; Quito-Avila, D.F.; Cabanas, D.; Bressan, A.; Wangai, A.; Baulcombe, D.C. , Maize chlorotic mottle virus exhibits low divergence between differentiated regional sub-populations. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 1173–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, L.; Galipienso, L.; Ferriol, I. , Detection of plant viruses and disease management: Relevance of genetic diversity and evolution. Frontiers in plant science 2020, 11, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, S.; Katzourakis, A.; Pybus, O.G. , Detecting natural selection in RNA virus populations using sequence summary statistics. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2010, 10, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Nielsen, R.; Goldman, N.; Pedersen, A.-M. K. , Codon-substitution models for heterogeneous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics 2000, 155, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M.; Gojobori, T. , Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Molecular biology and evolution 1986, 3, 418–426. [Google Scholar]

- Jewehan, A.; Kiemo, F.W.; Salem, N.; Tóth, Z.; Salamon, P.; Szabó, Z. , Isolation and molecular characterization of a tomato brown rugose fruit virus mutant breaking the tobamovirus resistance found in wild Solanum species. Archives of Virology 2022, 167, 1559–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisi, Z.; Ghijselings, L.; Vogel, E.; Vos, C.; Matthijnssens, J. , Single amino acid change in tomato brown rugose fruit virus breaks virus-specific resistance in new resistant tomato cultivar. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, A. , Evolution and origins of tobamoviruses. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 1999, 354, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraile, A.; García-Arenal, F. , Tobamoviruses as models for the study of virus evolution. Advances in virus research 2018, 102, 89–117. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.Y.; Ma, H.Y.; Wang, L.; Tettey, C.; Zhao, M.S.; Geng, C.; Tian, Y.P.; Li, X.D. , Identification of genetic determinants of tomato brown rugose fruit virus that enable infection of plants harbouring the Tm-22 resistance gene. Molecular Plant Pathology 2021, 22, 1347–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hak, H.; Raanan, H.; Schwarz, S.; Sherman, Y.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P.; Spiegelman, Z. , Activation of Tm-22 resistance is mediated by a conserved cysteine essential for tobacco mosaic virus movement. Molecular Plant Pathology 2023, 24, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaTourrette, K.; Holste, N.M.; Rodriguez-Peña, R.; Leme, R.A.; Garcia-Ruiz, H. , Genome-Wide Variation in Betacoronaviruses. J Virol 2021, 95, e0049621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, A.J.; Wood, J.; Garcia-Arenal, F.; Ohshima, K.; Armstrong, J.S. , Tobamoviruses have probably co-diverged with their eudicotyledonous hosts for at least 110 million years. Virus Evolution, 2015; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, J.; Yang, Y.; Sun, X.; Jiang, S.; Hong, H.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y. , Genetic Variability and Molecular Evolution of Tomato Mosaic Virus Populations in Three Northern China Provinces. Viruses, 2023; 15. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamian, P.; Cai, W.; Nunziata, S.O.; Ling, K.S.; Jaiswal, N.; Mavrodieva, V.A.; Rivera, Y.; Nakhla, M.K. , Comparative Analysis of Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus Isolates Shows Limited Genetic Diversity. Viruses, 2022; 14. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeilzadeh, F.; Santosa, A.I.; Çelik, A.; Koolivand, D. , Revealing an Iranian Isolate of Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus: Complete Genome Analysis and Mechanical Transmission. Microorganisms, 2023; 11. [Google Scholar]

- LaTourrette, K.; Garcia-Ruiz, H. , Determinants of virus variation, evolution, and host adaptation. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, H.-K.; Kim, I.-H.; Hu, W.-X.; Kim, B.; Choi, G.-W.; Kim, J.; Lim, Y.P.; Domier, L.L.; Hammond, J.; Lim, H.-S. , A single nucleotide change in the overlapping MP and CP reading frames results in differences in symptoms caused by two isolates of Youcai mosaic virus. Archives of virology 2019, 164, 1553–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, A.E.; El Mounadi, K.; Parperides, E.; Garcia-Ruiz, H. , Cell Fractionation and the Identification of Host Proteins Involved in Plant–Virus Interactions. Pathogens 2024, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, A.G.; Bertacca, S.; Parrella, G.; Rizzo, R.; Davino, S.; Panno, S. , Tomato brown rugose fruit virus: A pathogen that is changing the tomato production worldwide. Annals of Applied Biology 2022, 181, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewehan, A.; Salem, N.; Tóth, Z.; Salamon, P.; Szabó, Z. , Screening of Solanum (sections Lycopersicon and Juglandifolia) germplasm for reactions to the tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV). Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection 2022, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ruiz, H.; Diaz, A.; Ahlquist, P. , Intermolecular RNA recombination occurs at different frequencies in alternate forms of brome mosaic virus RNA replication compartments. Viruses 2018, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).