1. Introduction

Heart rate variability (HRV) analysis provides a non-invasive window into autonomic nervous system (ANS) function and has been widely applied in both physiological and clinical research. Numerous studies have demonstrated that HRV is influenced by various factors such as age, sex, circadian rhythm, sleep stages, and pathological conditions including cardiovascular and respiratory diseases [

1,

2,

3]. Among these modulators, sleep posture has received relatively little attention, despite its known effects on cardiovascular physiology, respiratory mechanics, and sleep architecture [

4,

5,

6].

Previous research has shown that supine posture may exacerbate obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and that lateral postures, particularly left lateral, may improve respiratory and cardiac function during sleep [

7,

8,

9].

However, most prior studies have been limited by small sample sizes, narrow age ranges, or laboratory-based settings, and the potential differences between the right and left lateral postures—particularly in terms of ANS activity—have not been well characterized. In the era of wearable sensors and large-scale physiological data, there is a growing opportunity to explore posture-specific variations in HRV across diverse populations and to determine whether such differences persist independently of sleep apnea status.

The Allostatic State Mapping by Ambulatory ECG Repository (ALLSTAR) is a nationwide database of over 730,000 24-hour Holter ECG recordings collected for clinical purposes in Japan [

10], which includes a substantial subset obtained using devices with a built-in triaxial actigraphic sensor. Leveraging this resource, we analyzed sleep posture patterns and posture-specific HRV parameters in a large, representative sample of more than 130,000 individuals spanning a wide age range.

Our objectives were threefold: (1) to characterize the distribution of sleep postures across age and sex groups, (2) to evaluate how HRV indices differ by sleep posture, and (3) to determine whether these posture-related differences are independent of potential confounders such as estimated sleep apnea severity. Understanding the influence of sleep posture on HRV may enhance the interpretation of ANS function in clinical settings and improve the utility of wearable ECG monitoring for sleep health assessment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. ALLSTAR Database

This study used the ALLSTAR database. The ALLSTAR project has started in 2007 in Japan and collected 738,461 Holter ambulatory ECGs recorded between November 2007 and March 2021. The 24-hr ECG data in this database were recorded for some clinical purpose(s) by medical facilities and were referred for analysis to three ECG analysis centers (Suzuken Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan) located in Tokyo, Nagoya, and Sapporo in Japan. The data were anonymized by the centers and stored with accompanying information, including age, sex, and recording date, time, and location (postal code).

Table 1 shows the characteristics of ALLSTAR subjects, including underlying cardiac diseases, cardiovascular risk factors, and medications, obtained from a randomized survey of 73,582 (10%) subjects.

The data used in this study were a subset of data consisting of 278,657 ECG that were recorded simultaneously with triaxial acceleration using wearable ECG devices with a built-in actigraphic sensor (Cardy 303 pico and Cardy 303 pico+, Suzuken Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan). These devices were attached to the skin on the subject’s upper chest and designed so that, when worn, their X, Y, and Z axes were always aligned with the subject’s head–foot, left–right, and front–back axes. The devices digitized three-channel ECG and triaxial acceleration at 125 and 31.25 Hz, respectively. The digitized data were analyzed with Holter ECG analyzers (Cardy Analyzer 05, Suzuken Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan); the temporal positions of all R waves were determined, the rhythm annotations were given to all QRS complexes, and all errors in the automated analysis were corrected manually by skilled medical technologists. The suspicious outcomes of the analysis have been reviewed by contracted cardiologists.

This table was reproduced from

Table 1 of a published article [

11]. The data were obtained from a random sampling survey of 73,582 subjects (10% of the population). Subjects with multiple diseases or taking multiple medications were counted more than once.

2.2. Data Selection

From the 278,657 ECG and acceleration recordings, the data for this study were selected stepwise according to the following criteria:

Recording duration >5 h between 22:00 and 08:00 in lying postures (assigned as supine, right lateral, left lateral, or prone segment by the method described in Posture Estimation section below).

80% of the nighttime lying data meeting criterion 1 are in sinus rhythm.

Finally, a random sample comprising 56% of the eligible data was selected. This percentage was determined based on the number of cases that could be processed within the allowable maximum computation time (one month).

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Posture Estimation

Posture was estimated from the X-, Y-, and Z-axis components of acceleration measured at 31.25 Hz using the following procedure. First, each acceleration component was passed through a 2–3 Hz band-pass filter to extract body movement components, and the magnitude of the composite vector was calculated as the root sum of squares of the three axes. The data were divided into 30-second segments; segments in which the maximum composite vector magnitude was ≥20 mG were classified as movement segments, and the others as non-movement segments.

Next, each acceleration component was passed through a low-pass filter with a corner frequency of 0.1 Hz to extract the gravitational component. The angles between the gravity acceleration vector estimated from the three axes and each body axis were then calculated. When the angle between the head–foot axis and the gravity vector was 90° ± 45°, the posture was classified as lying. In this case, if the angle with the front–back axis was 0°±45°, the posture was classified as supine; if 180° ± 45°, as prone; if the angle with the left–right axis was 0° ± 45°, as right lateral; and if 180° ± 45°, as left lateral.

Finally, among the non-movement segments, those in which a single posture accounted for >50% of the segment were labeled as that posture segment; segments with no single posture exceeding 50% were classified as transition segments. The percentage of each posture for each subject was calculated as the proportion of posture-labeled segments assigned to that posture among all posture-labeled segments.

2.3.2. Time Domain HRV Indices

R-R interval time series were divided into 30-second segments. For each segment, heart rate (HR) and standard deviation of R-R interval were calculated using only normal-to-normal R-R intervals within the segment.

2.3.3. Frequency Domain HRV Indices

The R–R interval time series, consisting only of normal-to-normal R–R intervals, was interpolated using a third-order spline function and resampled at 2 Hz. Complex demodulation [

12] was then applied for three frequency bands—very low frequency (VLF; 0.003–0.04 Hz), low frequency (LF; 0.04–0.15 Hz), and high frequency (HF; 0.15–0.40 Hz)—to extract, for each band, the amplitude and instantaneous frequency as continuous functions at a resolution of 2 Hz. The continuous functions were divided into 30-second segments, and values within each segment were averaged to obtain the amplitude and instantaneous frequency of the VLF, LF, and HF components. The LF-to-HF ratio (LF/HF) was then calculated for each segment.

2.3.4. Respiration Frequency Stability

The stability of respiratory frequency was estimated using the HF spectral power concentration index (Hsi) [

13]. To calculate Hsi, the 2-Hz resampled R–R interval time series was divided into overlapping 256-second segments (512 points), shifted at a step of 30 seconds. For each segment, the power spectrum was computed using the fast Fourier transform, and Hsi was defined as the ratio of power concentrated around the spectral peak of the HF component, as described in detail in reference [

16]. The Hsi value was assigned to the 30-second segment located at the center of each 256-second segment.

2.3.5. Cyclic Variation of Heart Rate (CVHR)

CVHR is a characteristic pattern of HRV that accompanies sleep apnea episodes [

14]. To estimate the temporal distribution of apnea-hypopnea episodes and severity of sleep apnea, CVHR was detected using a waveform analysis algorithm [

15]. The hourly frequency of CVHR during total nighttime lying segments in each subject was used to estimate the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI). Subjects were classified as having normal-to-mild sleep apnea when the estimated AHI was <15/h and as having moderate-to-severe sleep apnea when the value was ≥15/h. In addition, 30-second segments were classified as sleep-apnea–positive or sleep-apnea–negative depending on the presence or absence of CVHR during the segment.

2.3.6. Calculation of Indices for Each Posture

For each subject, HRV indices calculated for each 30-second segment were grouped according to the posture classification of that segment, and the mean value of each index was obtained for each posture. For CVHR, the value for each posture was calculated as the number of sleep-apnea–positive segments in that posture divided by the total hours spent in that posture.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Repeated-measures ANOVA using the GLM procedure was applied to evaluate differences in preferred sleep posture by age and sex. The same procedure was also used to assess the associations between HRV and other indices with posture, as well as the effects of age and sex on these associations. Because the effect of age was not linear, age groups in 10-year intervals (AGE10) were used. In addition, to verify that the relationships between posture and HRV indices were not attributable to an association between sleep apnea and posture, differences in the proportion of each posture according to sleep apnea severity were examined using the GLM procedure, and effect sizes were evaluated using η2.

Table 2.

Number of subjects.

Table 2.

Number of subjects.

| AGE10 |

Female |

Male |

Total |

| 0 |

302 (48.0%) |

327 (52.0%) |

629 (0.5%) |

| 10 |

1,490 (47.0%) |

1,678 (53.0%) |

3,168 (2.4%) |

| 20 |

1,667 (55.4%) |

1,341 (44.6%) |

3,008 (2.3%) |

| 30 |

3,175 (56.3%) |

2,463 (43.7%) |

5,638 (4.3%) |

| 40 |

6,097 (55.4%) |

4,903 (44.6%) |

11,000 (8.4%) |

| 50 |

8,024 (53.0%) |

7,128 (47.0%) |

15,152 (11.6%) |

| 60 |

14,337 (52.9%) |

12,777 (47.1%) |

27,114 (20.7%) |

| 70 |

22,414 (57.3%) |

16,728 (42.7%) |

39,142 (29.9%) |

| 80 |

13,941 (60.2%) |

9,226 (39.8%) |

23,167 (17.7%) |

| 90 |

1,977 (69.0%) |

890 (31.0%) |

2,867 (2.2%) |

| Total |

73,424 (56.1%) |

57,461 (43.9%) |

130,885 (100%) |

3. Results

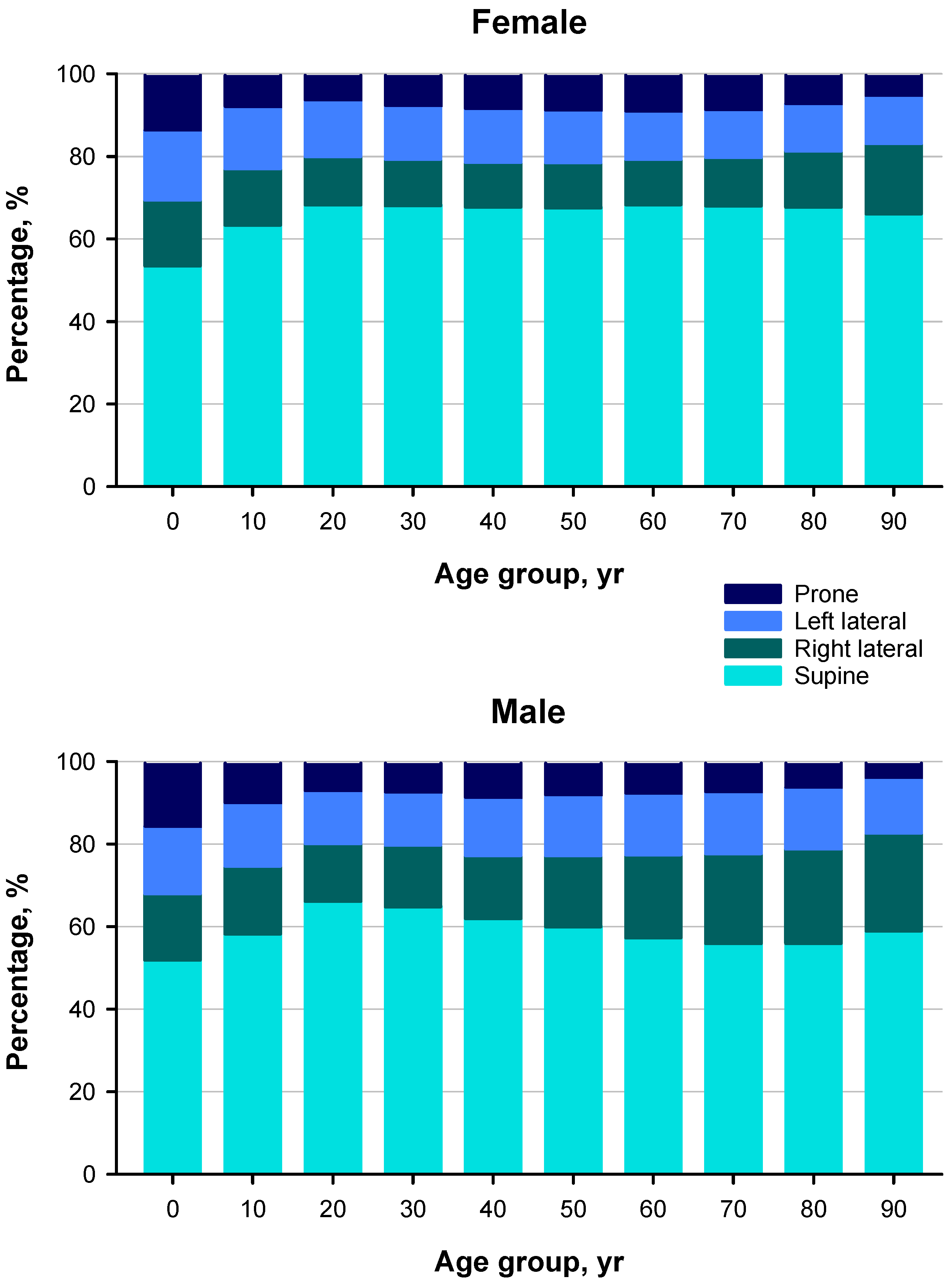

3.1. Sleep Posture Distribution and Its Variation with Age and Sex

Among the 278,657 subjects, >5 h of ECG data in sinus rhythm during lying posture between 22:00 and 08:00 were available for 233,723 (84%) subjects, from which 130,885 (56%) were randomly selected for analysis. The age and sex distribution of the analyzed cohort is shown in

Table 1.

In this cohort, the supine posture accounted for the largest proportion of sleep time across all age groups (

Figure 1). The proportion of supine sleep was consistently higher in females than in males. The proportion of right lateral posture increased slightly with age in females after their 40s and markedly in males after their 20s. Prone posture was the least frequent in all groups and declined markedly with age in both sexes.

3.2. HR and SDRR Across Sleep Postures

HR during nighttime lying varied across postures and age groups (Figures 2A and 3A). In both sexes, HR was lowest in the left lateral posture across all ages and highest in the right lateral posture, except in the oldest group (≥80 years), where it was highest in the prone posture.

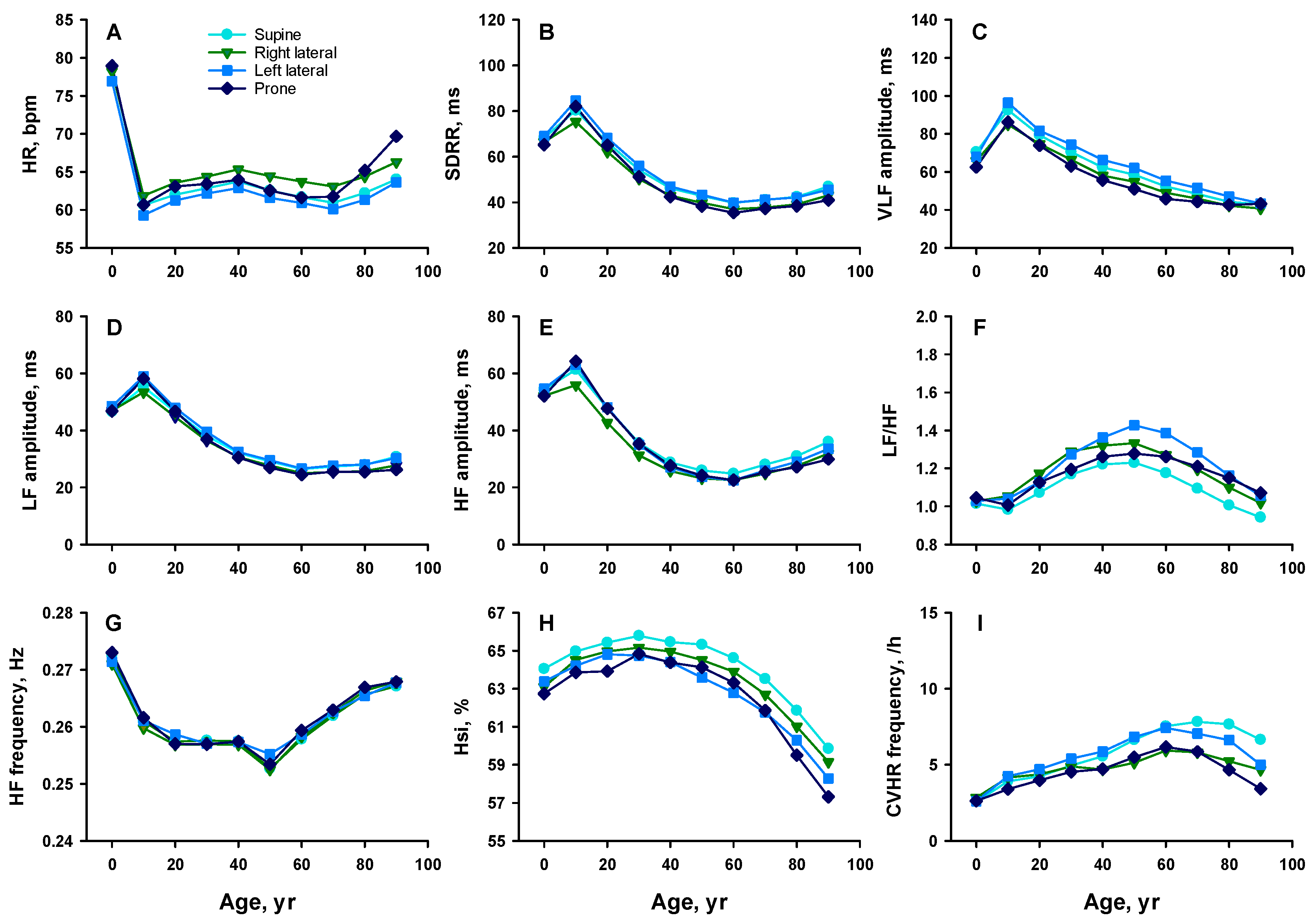

Figure 2.

Age-related changes in HR and HRV indices by sleep posture in females. Panel A: heart rate (HR); B: standard deviation of R–R intervals (SDRR); C: amplitude of the very low frequency (VLF) component; D: amplitude of the low frequency (LF) component; E: amplitude of the high frequency (HF) component; F: LF-to-HF ratio (LF/HF); G: frequency of the HF component; H: HF spectral power concentration index (Hsi); and I: frequency of cyclic variation of heart rate (CVHR). Colors indicate posture types: sky blue = supine, green = right lateral, blue = left lateral, and dark blue = prone.

Figure 2.

Age-related changes in HR and HRV indices by sleep posture in females. Panel A: heart rate (HR); B: standard deviation of R–R intervals (SDRR); C: amplitude of the very low frequency (VLF) component; D: amplitude of the low frequency (LF) component; E: amplitude of the high frequency (HF) component; F: LF-to-HF ratio (LF/HF); G: frequency of the HF component; H: HF spectral power concentration index (Hsi); and I: frequency of cyclic variation of heart rate (CVHR). Colors indicate posture types: sky blue = supine, green = right lateral, blue = left lateral, and dark blue = prone.

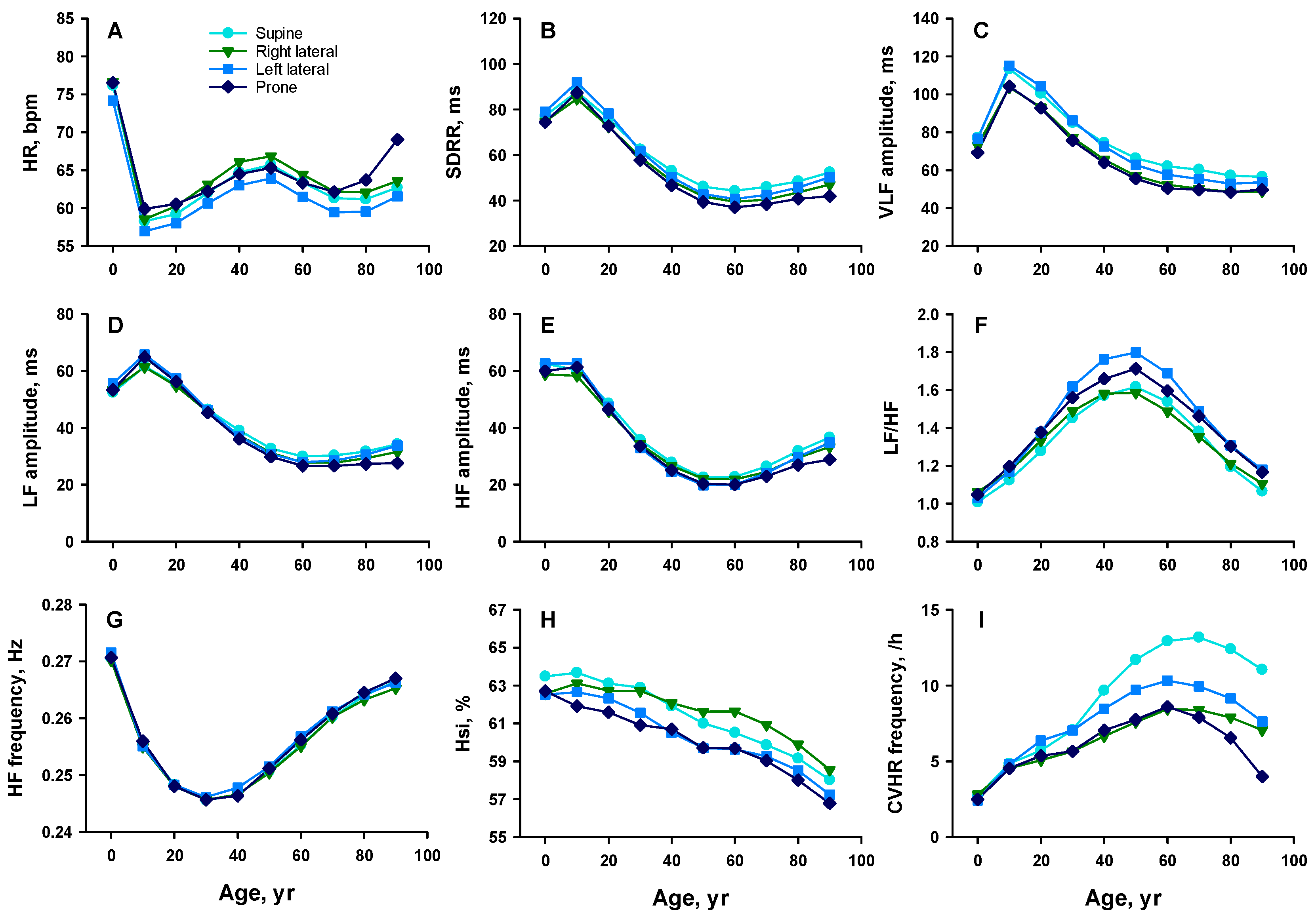

SDRR was highest in either the left lateral or supine posture, alternating with age, and lowest in either the prone or right lateral posture, also alternating with age (Figures 2B and 3B). Between the lateral postures, SDRR was consistently higher in the left lateral posture than in the right across all age and sex groups.

3.3. Frequency-Domain HRV Indices Across Sleep Postures

VLF amplitude was generally highest in the left lateral posture across all age groups in females (Figures 2C and 3C). In males, it was highest in the left lateral posture up to their 30s and in the supine posture thereafter. In both sexes, VLF was lowest in either the right lateral or prone posture, depending on age.

LF amplitude was highest in either the supine or left lateral posture, alternating by age, and lowest in the prone or right lateral posture in most age groups in both sexes, although the magnitude of postural differences was small (Figures 2D and 3D).

HF amplitude followed a similar trend, with higher values in the supine and left lateral postures than in the right lateral and prone postures, although the magnitude of postural differences was small (Figures 2E and 3E).

The LF/HF varied across postures and age groups (Figures 2F and 3F). In females, LF/HF was highest in the left lateral posture between their 40s and 80s, followed by the right lateral or prone posture, and lowest in the supine posture. In males, LF/HF was highest in the left lateral posture across all age groups after their 20s, followed by the prone posture, and lowest in either the supine or right lateral posture, alternating with age.

Although HF frequency was higher in females than in males between the 10s and 40s (Figures 2G and 3G), there was no significant difference with posture across all age and sex groups.

3.4. Hsi and CVHR Across Sleep Postures

Although Hsi was higher in females than in males between the 10s and 70s, it also exhibited posture-dependent variation (

Figure 2H and 3H). In females, Hsi was highest in the supine posture across all age groups. In males, Hsi was highest in the supine posture until their 30s and in the right lateral posture thereafter. In both sexes, Hsi was lowest in either the left lateral or prone posture, alternating with age.

Although the frequency of CVHR was higher in males than in females between the 20s and 70s, it also varied across postures and age (

Figure 2I and 3I). CVHR frequency was highest in the left lateral posture until the 50s in females and until the 30s in males, and was highest in the supine posture thereafter. In both sexes, CVHR frequency was lowest in either the right lateral or prone posture, alternating with age. Notably, CVHR frequency was consistently higher in the left lateral posture than in the right lateral posture.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Age-related changes in HR and HRV indices by sleep posture in males. The parameters presented in each panel and the abbreviations are described in the legend of

Figure 2. Colors indicate posture types: sky blue = supine, green = right lateral, blue = left lateral, and dark blue = prone.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Age-related changes in HR and HRV indices by sleep posture in males. The parameters presented in each panel and the abbreviations are described in the legend of

Figure 2. Colors indicate posture types: sky blue = supine, green = right lateral, blue = left lateral, and dark blue = prone.

3.5. Summary of Posture-Related Differences

Repeated-measures ANOVA confirmed significant main effects of posture, as well as significant posture × age group interactions (p < 0.0001) on all HRV indices but HF frequency (

Table 3). Posture × sex interactions were generally not significant. Despite variations in absolute values with age and sex, the relative differences among postures remained consistent.

Across multiple indices—including HR, SDRR, VLF, LF, HF, LF/HF, Hsi, and CVHR—physiological differences between the right and left lateral postures were consistently observed. These included lower HR, higher SDRR, higher VLF amplitude, greater LF and HF amplitudes, higher LF/HF, lower Hsi, and higher CVHR (in adults) in the left lateral posture compared to the right. These differences persisted regardless of age and sex, and were observed in both HR and HRV indices. These results highlight laterality as a significant factor influencing cardiorespiratory ANS activity during sleep.

3.6. Potential Confounding by Sleep Apnea Severity

Although group differences in sleep posture proportions across estimated sleep apnea severity were statistically significant, the effect size was negligible (η

2 < 0.0013,

Table 4). Therefore, these differences are unlikely to have materially influenced the posture-dependent variations in HRV indices.

4. Discussion

In this large clinical cohort, sleep posture patterns varied systematically with age and sex, and posture-specific HRV indices showed consistent laterality. Across most age groups in both sexes, HR was lower and SDRR, VLF, LF, HF, and CVHR were higher in the left lateral posture compared with the right lateral posture, whereas Hsi was lower. These differences persisted after accounting for estimated sleep apnea severity, which showed negligible association with posture distribution (η2 = 0.0013). Although statistically robust due to the large sample size, the effect sizes were generally small, and their clinical significance should be interpreted with caution.

Our findings extend previous reports that body position influences cardiovascular and respiratory function during sleep [

9,

16,

17]. Whereas most prior studies were limited by small samples, narrow age ranges, or laboratory settings [

9], our analysis included over 130,000 individuals from a nationwide Holter ECG database with concurrent posture monitoring, enabling detailed assessment of age-, sex-, and posture-specific autonomic differences.

Several physiological mechanisms may underlie the observed laterality. In the left lateral posture, gravitational effects may redistribute cardiac preload and pulmonary blood volume, reducing right atrial pressure and enhancing vagal modulation [

18]. Improved pulmonary mechanics—via reduced airway resistance and enhanced ventilation–perfusion matching [

19]—could further stabilize respiration and improve oxygenation, influencing HRV. Although previous studies generally reported that the right lateral posture is associated with higher HF and lower LF/HF [

20,

21,

22], our results showed only small HF differences and lower LF/HF in the right lateral posture, partially consistent with earlier reports but without clear vagal augmentation. One possible explanation is posture-induced alteration of baroreceptor loading via changes in cardiac filling pressures and venous return. Experimental work has shown that posture can modify baroreflex bandwidth [

23] and latency [

24], and that asymmetric carotid loading can influence reflex cardiovascular responses [

25]. Together with recent evidence questioning LF and LF/HF as direct sympathetic indices [

26] and suggesting LF reflects baroreflex sensitivity [

27], our findings may reflect subtle posture-related modulation of baroreflex function rather than pure sympathetic withdrawal.

The observed age- and sex-related changes in posture patterns may also be physiologically relevant. For example, the increase in right lateral posture with age in males, and the relatively stable supine preference in females, could interact with age-related changes in cardiovascular compliance, ANS control, and sleep-disordered breathing risk [

20]. While supine posture is known to exacerbate OSA [

9,

16], lateral positioning in general has been shown to reduce OSA severity compared with the supine position [

28,

29]. However, differences in OSA severity between the left and right lateral positions have not been well characterized in previous research. Our results suggest that intrinsic autonomic differences between left and right lateral postures exist independently of OSA status.

From a clinical perspective, these results highlight the importance of accounting for sleep posture when interpreting HRV metrics, particularly in wearable sensor–based sleep monitoring. Posture-specific HRV analysis could improve physiological interpretation, refine risk stratification, and enhance the clinical utility of long-term ambulatory ECG data.

Limitations — This study has several limitations:

(1) Sleep stages were not available, so posture-specific differences could not be disentangled from stage-specific autonomic changes.

(2) Sleep apnea severity was estimated using ECG-based CVHR detection, which has lower sensitivity for mild or REM-related OSA.

(3) Posture classification was based on accelerometer thresholds (±45°), which may not capture oblique or transient positions.

(4) The cohort consisted of individuals referred for clinical Holter ECG, so findings may not generalize to the healthy population.

(5) Although statistically significant, many posture-related differences had small effect sizes, and their clinical relevance should be interpreted with caution.

Future studies combining wearable ECG with validated posture and sleep stage classification could help clarify these associations.

5. Conclusions

Sleep posture is a significant and independent determinant of HRV indices in a large clinical population. Consistent laterality in autonomic activity between left and right lateral postures was observed across age and sex groups, largely independent of sleep apnea severity. Posture-specific analysis should be incorporated into research protocols and clinical interpretations of ANS function during sleep, especially as wearable ECG monitoring becomes more widespread.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Y.; methodology, E.Y. and J.H.; software, J.H.; validation, E.Y.; formal analysis, J.H.; investigation, J.H.; resources, E.Y. and J.H.; data curation, E.Y. and J.H; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing, E.Y.; visualization, J.H.; project administration, J.H. The authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was a part of the Allostatic State Mapping by Ambulatory ECG Repository (ALLSTAR) project that has been approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences (No. 60-00-0709).

Informed Consent Statement

For the purpose of the ALLSTAR research project, the data were anonymized and stored with subjects’ age, sex, and recording date, time, and location (postal code). Additionally, according to the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects (by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan, December 22, 2014), the purpose and information utilized in this project have been public through the project’s homepages (

http://www.med.nagoya-cu.ac.jp/mededu.dir/allstar/index.html), in which opportunities to re-fuse the uses of information are ensured for the research subjects.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions of the ALLSTAR project.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Suzuken Co., Ltd. for the support for the construction and management of the ALLSTAR database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HRV |

Heart rate variability |

| ANS |

Autonomic nervous system |

| OSA |

obstructive sleep apnea |

| ALLSTAR |

Allostatic State Mapping by Ambulatory ECG Repository |

| HR |

Heart rate |

| VLF |

Very low frequency |

| LF |

Low frequency |

| HF |

High frequency |

| LF/HF |

LF-to-HF ratio |

| Hsi |

HF spectral power concentration index |

| CVHR |

Cyclic variation of heart rate |

| AHI |

Apnea-hypopnea index |

References

- Tiwari, R.; Kumar, R.; Malik, S.; Raj, T.; Kumar, P. Analysis of Heart Rate Variability and Implication of Different Factors on Heart Rate Variability. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2021, 17, e160721189770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakaki, X.; Arechavala, R.J.; Choy, E.H.; Bautista, J.; Bliss, B.; Molloy, C.; Wu, D.A.; Shimojo, S.; Jiang, Y.; Kleinman, M.T.; et al. . The connection between heart rate variability (HRV), neurological health, and cognition: A literature review. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1055445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, D.; Eser, P.; Omlin, X.; Riener, R.; Wilhelm, M.; Achermann, P. Reproducibility of Heart Rate Variability Is Parameter and Sleep Stage Dependent. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, R.; Schulze, K.F.; Kashyap, S.; Ohira-Kist, K.; Myers, M.M.; Fifer, W.P. Body position, sleep states, and cardiorespiratory activity in developing low birth weight infants. Early Hum. Dev. 1999, 54, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceridon, M.L.; Morris, N.R.; Olson, T.P.; Lalande, S.; Johnson, B.D. Effect of supine posture on airway blood flow and pulmonary function in stable heart failure. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2011, 178, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeghiazarians, Y.; Jneid, H.; Tietjens, J.R.; Redline, S.; Brown, D.L.; El-Sherif, N.; Mehra, R.; Bozkurt, B.; Ndumele, C.E.; Somers, V.K. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 144, e56–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksenberg, A.; Silverberg, D.S. The effect of body posture on sleep-related breathing disorders: facts and therapeutic implications. Sleep. Med. Rev. 1998, 2, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, S.A.; Edwards, B.A.; Wellman, A.; Turton, A.; Skuza, E.M.; Berger, P.J.; Hamilton, G.S. The Effect of Body Position on Physiological Factors that Contribute to Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Sleep. 2015, 38, 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, S.A.; Beatty, C.; Thomson, L.D.J.; Wong, A.M.; Edwards, B.A.; Hamilton, G.S.; Joosten, S.A. A review of supine position related obstructive sleep apnea: Classification, epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2023, 72, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Nakamura, T.; Hayano, J.; Yamamoto, Y. Age and gender differences in objective sleep properties using large-scale body acceleration data in a Japanese population. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuda, E.; Ueda, N.; Kisohara, M.; Hayano, J. Redundancy among risk predictors derived from heart rate variability and dynamics: ALLSTAR big data analysis. Annals of noninvasive electrocardiology : the official journal of the International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology, Inc. 2020; e12790. [Google Scholar]

- Hayano, J.; Taylor, J.A.; Yamada, A.; Mukai, S.; Hori, R.; Asakawa, T.; Yokoyama, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Takata, K.; Fujinami, T. Continuous assessment of hemodynamic control by complex demodulation of cardiovascular variability. Am. J. Physiol. 1993, (4 Pt 2) Pt 2, H1229–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayano, J.; Ueda, N.; Kisohara, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Yuda, E. Non-REM Sleep Marker for Wearable Monitoring: Power Concentration of Respiratory Heart Rate Fluctuation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilleminault, C.; Connolly, S.; Winkle, R.; Melvin, K.; Tilkian, A. Cyclical variation of the heart rate in sleep apnoea syndrome. Mechanisms, and usefulness of 24 h electrocardiography as a screening technique. Lancet 1984, 1, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayano, J.; Watanabe, E.; Saito, Y.; Sasaki, F.; Fujimoto, K.; Nomiyama, T.; Kawai, K.; Kodama, I.; Sakakibara, H. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea by cyclic variation of heart rate. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2011, 4, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksenberg, A.; Silverberg, D.S.; Arons, E.; Radwan, H. Positional vs nonpositional obstructive sleep apnea patients: anthropomorphic, nocturnal polysomnographic, and multiple sleep latency test data. Chest 1997, 112, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, S.A.; O’Driscoll, D.M.; Berger, P.J.; Hamilton, G.S. Supine position related obstructive sleep apnea in adults: pathogenesis and treatment. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2014, 18, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolter, C.P.; Wilson, S.J. Influence of right atrial pressure on the cardiac pacemaker response to vagal stimulation. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 276, R1112–R1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.C.; Moore, D.M.; Cleland, J.G.; Pride, N.B. Effect of supine posture on respiratory mechanics in chronic left ventricular failure. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 162 Pt. 1, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, S.; Fujita, M.; Sekiguchi, H.; Okano, Y.; Nagaya, N.; Ueda, K.; Tamaki, S.; Nohara, R.; Eiho, S.; Sasayama, S. Effects of posture on cardiac autonomic nervous activity in patients with congestive heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 1788–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.D.; Chen, G.Y. Comparison of three recumbent positions on vagal and sympathetic modulation using spectral heart rate variability in patients with coronary artery disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 1998, 81, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, K.; Haga, M.; Bao, S.; Sato, H.; Saiki, Y.; Maruyama, R. The Cardiac Sympathetic Nerve Activity in the Elderly Is Attenuated in the Right Lateral Decubitus Position. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2017, 3, 2333721417708071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, A.; Gelpi, F.; Bari, V.; Cairo, B.; De Maria, B.; Takahashi, A.C.M.; Catai, A.M.; Colombo, R. Changes of the cardiac baroreflex bandwidth during postural challenges. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2023, 324, R601–r612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulli, G.; Cooper, V.L.; Claydon, V.E.; Hainsworth, R. Prolonged latency in the baroreflex mediated vascular resistance response in subjects with postural related syncope. Clin. Auton. Res. 2005, 15, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, R.; Diedrich, A.; Rimoldi, A.; Palazzolo, L.; Porta, C.; Diedrich, L.; Harris, P.A.; Sleight, P.; Biagioni, I.; Robertson, D.; et al. Effects of unilateral and bilateral carotid baroreflex stimulation on cardiac and neural sympathetic discharge oscillatory patterns. Circulation 2003, 108, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billman, G.E. The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, D.S.; Bentho, O.; Park, M.Y.; Sharabi, Y. Low-frequency power of heart rate variability is not a measure of cardiac sympathetic tone but may be a measure of modulation of cardiac autonomic outflows by baroreflexes. Exp. Physiol. 2011, 96, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, R.D. Effect of sleep position on sleep apnea severity. Sleep. 1984, 7, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mador, M.J.; Kufel, T.J.; Magalang, U.J.; Rajesh, S.K.; Watwe, V.; Grant, B.J. Prevalence of positional sleep apnea in patients undergoing polysomnography. Chest 2005, 128, 2130–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).