1. Introduction

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a potentially life-threatening cardiovascular emergency resulting from the obstruction of the pulmonary arteries by embolic material, typically thrombi originating from deep veins in the lower extremities. PE is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with an estimated incidence of 60 to 70 cases per 100,000 individuals annually. The clinical presentation of PE is highly variable, ranging from asymptomatic to sudden death, which makes timely diagnosis particularly challenging [

1]. Therefore, fast and accurate diagnostic tools are essential to improve patient outcomes and reduce healthcare burden.

Computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA or CTA) has become the gold standard for the noninvasive diagnosis of PE. It offers high-resolution cross-sectional imaging of the pulmonary vasculature, enabling the detection of emboli based on contrast-filling defects. Given its widespread clinical use, CTA can be viewed as a modern biosensing platform capable of capturing spatially and temporally resolved pathophysiological data. However, manual analysis of CTA images is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and subject to interobserver variability, particularly when emboli are small or located in peripheral branches [

2]. These limitations highlight the need for intelligent image analysis systems that can assist clinicians by providing rapid, consistent, and interpretable segmentation of embolism regions.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly in the domain of deep learning, have revolutionized the field of medical image analysis [

3]. Deep learning models, especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have demonstrated remarkable performance in various diagnostic tasks, including classification, segmentation, detection, and registration. Among these, fully convolutional networks (FCNs) have gained significant traction in biomedical image segmentation due to their end-to-end learning capability and pixel-level prediction accuracy. FCNs can be trained to automatically detect and delineate complex anatomical or pathological structures in medical images, reducing the reliance on manual annotation and potentially improving diagnostic throughput and accuracy.

Despite the advantages of FCNs, challenges remain in achieving consistent and generalizable segmentation performance, especially when training data is limited or when model architecture exhibits variability in sensitivity to image features. One practical approach to improving robustness is the use of model ensembles, where multiple trained models contribute to the final prediction. Ensemble methods can reduce variance, mitigate overfitting, and leverage the diversity of model outputs to enhance segmentation reliability. Traditional ensemble strategies, such as averaging or majority voting, have been employed in medical imaging studies. However, these methods may not be optimized for semantic overlap, which is crucial in segmentation tasks where alignment with ground truth regions is essential.

To address this limitation, we propose a novel ensemble strategy called Consensus Intersection-Optimized Fusion (CIOF). CIOF is designed to intelligently combine the outputs of multiple FCN models by emphasizing intersection consensus and minimizing false-positive inclusion. Rather than relying solely on simple majority voting, CIOF adaptively searches for the voting threshold that yields the maximum intersection with the ground truth while minimizing the union, thus optimizing the Intersection-over-Union (IoU) metric. This approach emulates signal enhancement strategies in biosensor networks, where multiple sensing signals are fused to improve sensitivity and specificity. CIOF enhances the stability and accuracy of segmentation in complex biomedical images such as CTA scans of pulmonary embolism.

In this study, we applied the CIOF fusion method with ten FCN models trained on the FUMPE dataset, consisting of 2,304 CTA slices with expert-annotated PE masks. Five architectures were each trained with Adam and SGDM optimizers. CIOF significantly outperformed individual models in missed detection and segmentation accuracy. This study contributes a comparative evaluation of FCNs, introduces CIOF as an effective fusion strategy, and demonstrates the potential for integrating AI-driven segmentation into biosensing diagnostic frameworks. The following sections detail the methods, results, discussion, and conclusions.

2. The Related Works

2.1. Deep Learning-Based Segmentation & Detection of PE

The adoption of deep learning in pulmonary embolism (PE) detection and segmentation has significantly enhanced diagnostic accuracy and automation in computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA). Numerous convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and advanced segmentation architectures have been proposed to address the challenge of localizing emboli within complex vascular structures. Kahraman et al. demonstrated that deep learning-based segmentation models substantially improved PE detection sensitivity in CTPA scans [

1]. Djahnine et al. introduced a 3D fully automated system capable of both PE detection and severity quantification using volumetric CT data [

2]. Bushra et al. designed a dual-pronged classifier-guided attention CNN to fuse global and local imaging features for improved sensitivity [

3]. Likewise, nnU-Net architectures have shown robust clot volume estimation and PE localization across different patient populations [

4]. Fan et al. proposed multiscale 3D segmentation frameworks including the Threshold Adjustment Segmentation Network (TSNet), which adaptively refines segmentation boundaries for enhanced detection performance [

5,

6].

In speed-focused approaches, Wu et al. presented SPE-YOLO and an accelerated tandem framework achieving near millisecond-level inference, showing great potential for emergency triage [

7,

8]. Zhu et al. employed 3D CNNs specifically optimized for CTPA data to achieve accurate embolism detection [

9]. Innovative models such as multitask networks that predict both PE presence and RV/LV ratio have also emerged, exemplified by Ma et al.’s work [

10]. Moreover, Khan et al. highlighted the potential of IoMT-integrated deep learning frameworks for remote PE diagnosis [

11].

Despite this progress, Li et al. emphasized the need for further studies addressing model generalizability, interpretability, and integration in clinical workflows [

12]. Enhanced region-based CNNs like the Mask R-CNN adaptation by Doğan et al. offer yet another strategy for precise PE localization and segmentation [

13]. Collectively, these advancements illustrate the growing maturity of deep learning models in PE detection, with continuous refinements in model accuracy, computational efficiency, and clinical interpretability.

2.2. Ensemble, Group Models & Weak Supervision Approaches

To improve robustness and generalization in pulmonary embolism (PE) detection, ensemble learning and weakly supervised methods have gained traction. These approaches leverage multiple models or learn from limited annotation data to reduce bias, improve segmentation accuracy, and enhance generalization across diverse clinical settings. Aydoğan-Balik et al. assessed the performance of deep ensemble systems for detecting both segmental and subsegmental PE, demonstrating that combining models significantly improves diagnostic accuracy and reduces false negatives, particularly in challenging anatomical regions [

14]. Such ensemble methods allow for model diversity and mitigate the limitations of individual network predictions.

Weakly supervised approaches have also shown promise. Hu et al. introduced a semi-weakly supervised framework for PE diagnosis that achieved high performance while reducing the reliance on extensive pixel-level annotations. This method utilized fewer labeled examples, offering a more scalable and resource-efficient approach to model training [

15]. Islam et al. explored multiple ensemble configurations across datasets and emphasized that optimal ensemble strategies must be dataset-aware, as model performance varies with imaging protocols and patient populations. Their findings underline the necessity of adaptive ensembling tailored to real-world variability in clinical data [

16]. Biret et al. proposed an integrated deep learning architecture combining multiple networks in a cohesive ensemble structure. Their results reinforced the value of architecture-level integration to capture complementary features and minimize missed detections in PE analysis [

17].

Additionally, a comparative study by Islam et al. in Medical Image Analysis stressed the need for methodological transparency in ensemble design. They provided a comprehensive evaluation of ensemble vs. single-model methods across datasets and suggested best practices for deployment in clinical workflows [

18]. These studies highlight that ensemble and weak supervision strategies offer practical solutions to overcome data scarcity, model overfitting, and inter-institutional variability in PE detection

2.3. Systematic Reviews & Broader Surveys

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been conducted to evaluate the current landscape of artificial intelligence (AI) applications in pulmonary embolism (PE) detection, offering insights into the strengths and limitations of existing methods. These reviews help synthesize diverse findings and inform future research directions.

Abdulaal et al. conducted a comprehensive systematic review on AI tools specifically targeting chronic PE using CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA), identifying various algorithms focused on chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) and highlighting the need for standardized validation metrics across studies [

19]. This work emphasized the gap between algorithmic development and clinical deployment, underscoring the importance of clinical validation before AI tools are widely adopted. Gao et al. provided a broader perspective by reviewing deep learning applications in lung nodule detection and segmentation, which shares methodological relevance with PE segmentation tasks. Their review cataloged various convolutional neural networks and transformer-based models, noting challenges in interpretability and generalizability across imaging settings [

20]. A recent meta-analysis by Lanza et al. systematically examined the reliability of AI-based PE detection, concluding that while many models report high diagnostic performance, significant heterogeneity exists due to dataset differences, lack of external validation, and inconsistent reporting of metrics [

21].

These reviews establish a foundational understanding of current AI capabilities and guide future efforts to ensure reliability and translational value in PE imaging research.

2.4. Clinical Validation, IoMT & Real-World AI Tools

To bridge the gap between laboratory performance and clinical usability, several recent studies have focused on validating AI models in real-world pulmonary embolism (PE) detection settings, often integrating Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) or evaluating retrospective clinical data. Fan et al. proposed the Threshold Segmentation Network (TSNet), which effectively detects PE in three-dimensional CTPA images with clinical validation demonstrating competitive segmentation performance on large datasets [

22]. Their work illustrates how model sensitivity can be tailored by threshold tuning based on anatomical localization.

The impact of AI on acute care diagnostics is exemplified by Planquette et al., who utilized deep learning to analyze the prevalence and characteristics of PE in COVID-19 patients. Their findings provided insights into PE occurrence in a pandemic context, validated on real-world hospital imaging data [

23]. A broader epidemiological perspective is presented by Gottlieb et al., who analyzed PE diagnosis and management trends over eight years across U.S. emergency departments. While not an AI model study per se, their data contextually supports the need for rapid, accurate PE tools in diverse clinical environments [

24].

Ben Yehuda et al. demonstrated the practical utility of AI in early PE prediction by applying a machine learning model at hospital admission to identify high-risk patients, revealing potential new risk factors through model interpretability [

25]. This approach highlights IoMT’s role in real-time risk stratification. Moreover, Hagen et al. validated an AI-based algorithm for detecting small PEs on unenhanced CT scans, showcasing strong diagnostic performance without contrast agents, thus offering safer options for renal-impaired patients [

26]. Complementarily, D’Angelo et al. employed dual-energy CT with electron density and Z-effective mapping to detect PE without contrast, pushing the boundary of non-invasive imaging AI [

27].

These studies exemplify AI’s translation from algorithmic development to clinical application, reinforcing its potential for enhancing PE diagnosis in diverse and resource-constrained settings

2.5. Supporting Cardiovascular Imaging & Anatomical Segmentation

Effective detection of pulmonary embolism (PE) requires an understanding of both the embolic burden and the surrounding anatomical structures, particularly the cardiovascular system. Deep learning methods have increasingly been applied not only for detecting PE but also for enhancing the anatomical segmentation of key regions within CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) datasets.

Huhtanen et al. introduced a weakly-supervised model combining InceptionResNetV2 and LSTM, which processes CTPA data in a stack-wise manner to identify embolic lesions while preserving anatomical context, offering robustness in cases with limited annotation [

28]. Their approach captures temporal dependencies and spatial continuity within axial slices, crucial for consistent cardiovascular imaging. Pu et al. developed a fully automated deep learning pipeline for PE detection and segmentation that eliminates the need for manual outlining, significantly streamlining clinical workflows and demonstrating generalizability across datasets [

29]. The model’s segmentation capacity allows for precise embolism localization in relation to vascular structures.

To facilitate integrated cardiovascular diagnostics, Sharkey et al. proposed a deep learning solution for automatic segmentation of the heart and great vessels in CTPA scans. Their work supports comprehensive cardiovascular assessments, particularly in emergency scenarios where both cardiac and embolic evaluations are essential [

30]. Lastly, Weikert et al. provided clinical validation of an AI-powered algorithm capable of detecting PE while accurately localizing emboli within vascular structures, thus reinforcing the importance of anatomical precision in AI-aided diagnostics [

31].

These studies emphasize that accurate segmentation of anatomical structures surrounding PE is critical for diagnostic confidence and downstream clinical decision-making.

3. Materials and Methods

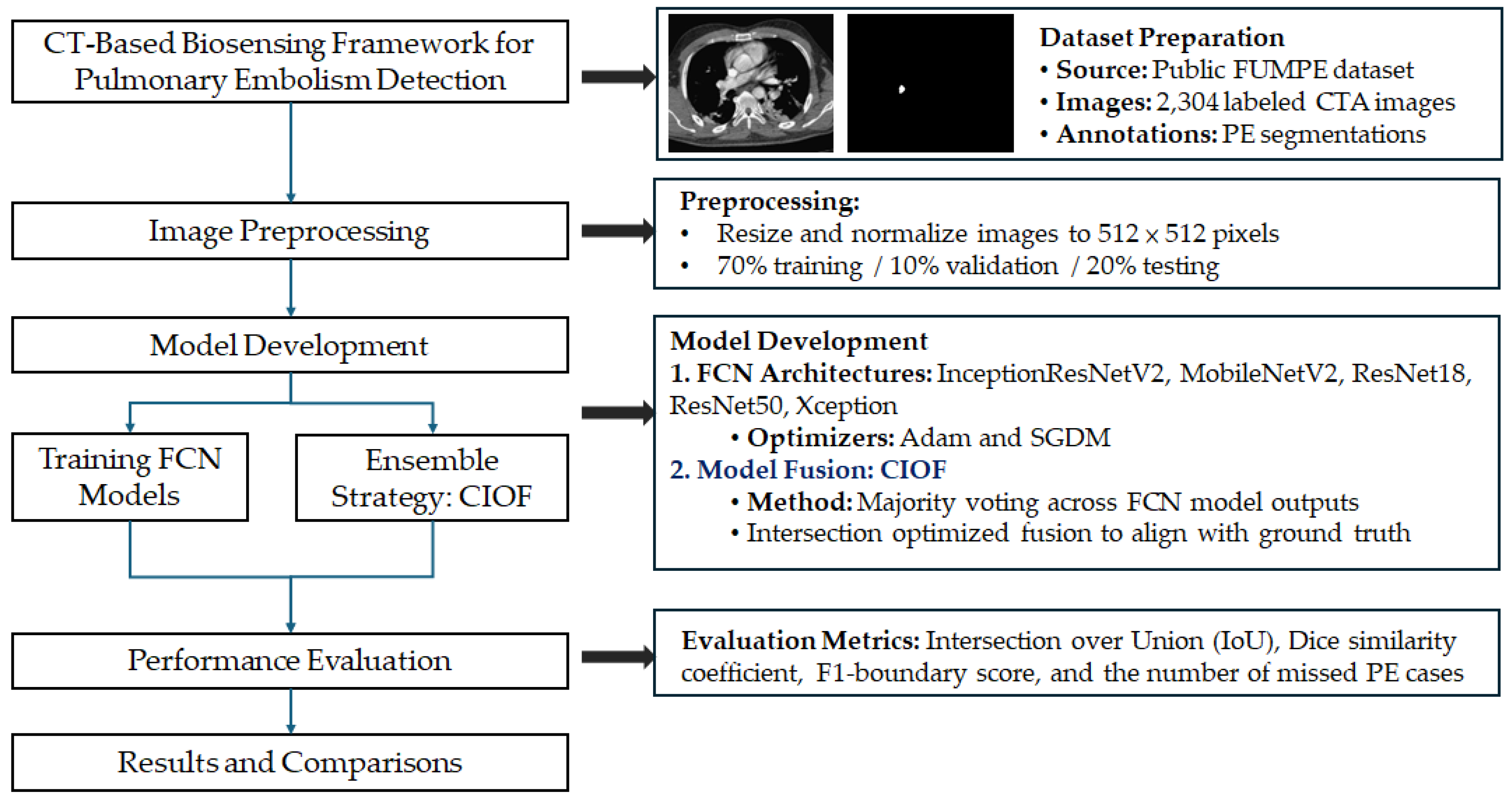

To systematically address the challenge of accurate pulmonary embolism (PE) detection and segmentation from computed tomography angiography (CTA) images, we designed a CT-based biosensing deep learning framework. The overall pipeline of the proposed methodology is illustrated in

Figure 1, encompassing stages from dataset preprocessing and model training to ensemble integration and performance evaluation. This structured approach ensures reproducibility and facilitates comparative analysis across different model architectures.

3.1. Dataset Description

The dataset used in this study is sourced from a publicly available repository on Kaggle (

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/andrewmvd/pulmonary-embolism-in-ct-images, accessed on 6 March 2025). Known as the FUMPE dataset (Ferdowsi University of Mashhad’s Pulmonary Embolism dataset), it comprises a total of 8,792 computed tomography angiography (CTA) slices collected from 35 patients. Each image is labeled as either Embo (with pulmonary embolism) with sample size 2,304 or noEmbo (without embolism) with sample size 6,488.

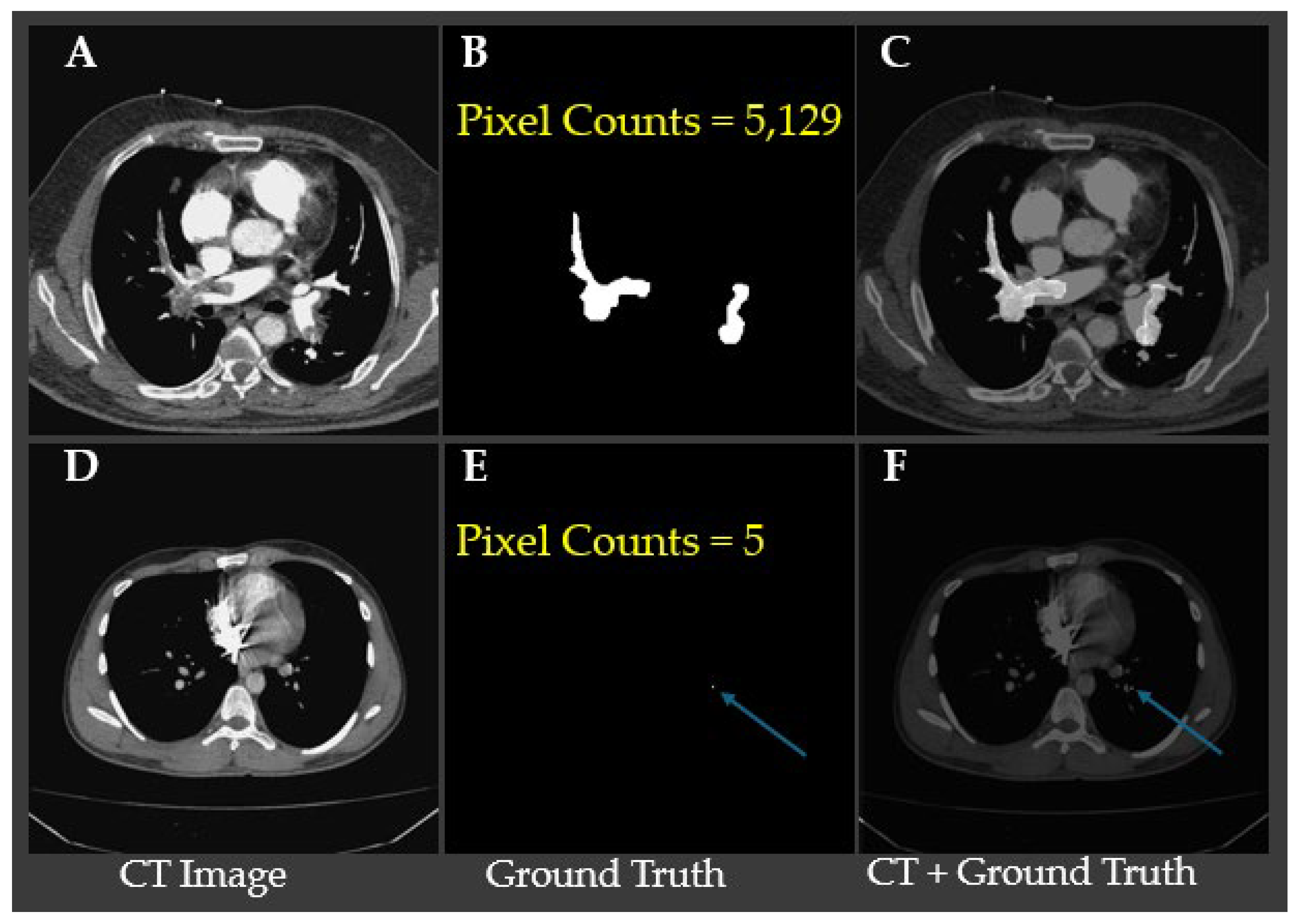

Table 1 shows small emboli (<26 pixels), which typically indicate embolization located in sub millimeter vessels, are relatively rare, occurring in only 63 slices with a ratio of embolization in image lower than 0.0001. This distribution highlights that the majority of detected pulmonary embolisms involve medium to large-sized clots, which may have clinical implications for model sensitivity and detection performance.

Figure 2. Representative CTA slices illustrating the largest and smallest annotated pulmonary embolism regions. Panels A–C show a case with the largest embolic region (5,129 pixels), where (B) displays the ground truth segmentation and (C) overlays the embolism on the CT slice. Panels D–F demonstrate the smallest annotated embolism in the dataset, consisting of only 5 pixels, with the location indicated by blue arrows in (E) and (F). These examples underscore the substantial variability in embolism size and highlight the challenge of detecting minute emboli, which requires high model sensitivity and precise localization to avoid false negatives.

3.2. Image Preprocessing

Image intensities were normalized using Hounsfield Unit (HU) windowing with brain or lung windows depending on model input strategies. For models requiring fixed input dimensions, 2D axial slices were extracted with size 512×512 pixels. Data augmentation techniques including random rotations, flipping, intensity jittering, and elastic deformation were applied to enhance generalizability.

3.3. Model Architectures

The proposed workflow (

Figure 1) integrates fully convolutional networks (FCNs) with a decision-level fusion strategy for robust pulmonary embolism (PE) segmentation. All computed tomography angiography (CTA) images are first resized to a standardized resolution of 512×512×3. Each image is then converted into an RGB composite using three input channels: bone window, brain window, and their average, in order to enhance contrast and improve vascular structure visualization for better clot localization.

A total of five pre-trained semantic segmentation backbones is employed in the FCN framework: InceptionResNetV2, Xception, MobileNetV2, ResNet50, and ResNet18. Each backbone is trained separately with two optimization strategies—ADAM and Stochastic Gradient Descent with Momentum (SGDM)—resulting in a total of 10 model variants. Each model independently produces a binary segmentation mask to localize embolism regions (EMBO class) from the input CTA slices. The predicted probability maps are thresholded to generate binarized segmentation masks.

To quantify model contribution to fusion, we define the Consensus Intersection Over Fusion (CIOF) metric as Equation (1).

where

TPmodel∩fusion is the number of pixels that are true positives in both the individual model and the fusion mask.

TPfusion is the total number of true positives in the fusion mask.

To enhance robustness and reduce false positives, a majority voting fusion strategy is applied. Specifically, the segmentation masks from selected models are aggregated on a pixel-wise basis, and a final fused segmentation mask is generated when at least two out of ten models agree. This ensemble approach increases the reliability of identifying small or subtle embolic regions that may not be consistently captured by any single model. Moreover, CIOF scores provide insight into each model’s alignment with the consensus result, emphasizing which architecture contribute most effectively to the final decision. Higher CIOF values indicate stronger model-fusion agreement, particularly valuable when detecting difficult-to-localize clots (see examples in

Figure 2). This modular architecture balances segmentation accuracy, model interpretability, and clinical applicability, while maintaining flexibility for future integration with advanced model ensembling or retraining strategies.

3.4. Training Details

All models were trained using the Adam and SGDM optimizers with an initial learning rate of 1e-4 and batch size of 30. A 5-fold cross-validation scheme was applied to assess model generalizability. The loss functions included Dice Loss for segmentation, Binary Cross-Entropy for classification, and a composite loss (Dice + Focal) for class-imbalanced scenarios. Training was conducted for 500 epochs with early stopping based on validation Dice coefficient.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

Model performance was quantitatively evaluated using several standard metrics, including the Dice coefficient, Intersection over Union (IoU), area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, and F1-score. In addition, a clinical-level metric—the count of missed detection—was used to assess potential diagnostic failures, reflecting the clinical impact of false negatives in pulmonary embolism detection. The formula of rate of missed detection is Equation (2).

where #{IoU=0} is the number of test samples where the Intersection over Union (IoU) between the predicted segmentation and the ground truth is exactly zero (i.e., model completely missed embolism) and Total Samples = #{IoU>0} + #{IoU=0}.

4. Results

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the segmentation performance of various deep learning models and the proposed CIOF method for pulmonary embolism (PE) detection in CTA images. The analysis is stratified by embolization ratios to assess model sensitivity under varying clot burdens. Key performance metrics, including Dice coefficient, Intersection over Union (IoU), and F1-score, are reported to quantify segmentation accuracy. In addition, detection rates (P(IoU > 0)) are analyzed to understand clinical applicability, especially in challenging scenarios involving small emboli. The results highlight both the effectiveness and limitations of each method, providing insights into their diagnostic value.

4.1. The Performance of Segmentation of Models

Table 1 summarizes the mean Intersection over Union (IoU), Dice coefficient, and F1 score for the segmentation performance of ten fully convolutional network (FCN) models and the proposed CIOF ensemble method. Among all models, CIOF achieved the highest scores across all three metrics: a mean IoU of 0.649, a Dice score of 0.765, and an F1 score of 0.394, demonstrating superior segmentation performance. In contrast, individual models such as xception-sgdm yielded the lowest results (IoU: 0.232, Dice: 0.317, F1: 0.317), highlighting the variability in performance depending on both model architecture and optimization algorithm. Notably, resnet50-sgdm and inceptionresnetv2-sgdm also performed relatively well (Dice: 0.630 and 0.704, respectively) yet still fell short of the ensemble-based CIOF. These findings suggest that integrating predictions from multiple FCNs provides a more robust and accurate segmentation solution for pulmonary embolism detection.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison of segmentation performance across different FCN architectures and the proposed CIOF method.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison of segmentation performance across different FCN architectures and the proposed CIOF method.

| Method |

Mean IoU |

Mean Dice |

Mean F1 Score |

| CIOF |

0.649 |

0.765 |

0.394 |

| InceptionResNetV2 + Adam |

0.440 |

0.554 |

0.554 |

| InceptionResNetV2 + SGDM |

0.586 |

0.704 |

0.704 |

| MobileNetV2 + Adam |

0.466 |

0.586 |

0.586 |

| MobileNetV2 + SGDM |

0.378 |

0.490 |

0.490 |

| ResNet18 + Adam |

0.460 |

0.569 |

0.569 |

| ResNet18 + SGDM |

0.426 |

0.538 |

0.538 |

| ResNet50 + Adam |

0.492 |

0.608 |

0.608 |

| ResNet50 + SGDM |

0.518 |

0.630 |

0.630 |

| Xception + Adam |

0.390 |

0.490 |

0.490 |

| Xception + SGDM |

0.232 |

0.317 |

0.317 |

To evaluate model performance across varying embolic burden levels, segmentation results were stratified by the ratio of embolization within CTA images: <0.0001, 0.0001–0.001, and >0.001. Metrics analyzed include mean Intersection over Union (IoU), Dice coefficient, and F1-score (

Table 2).

Across all embolization ratios, the proposed CIOF method consistently outperformed all deep learning models. For images with extremely small embolic regions (<0.0001 ratio), CIOF achieved a mean IoU of 0.445, Dice coefficient of 0.568, and F1-score of 0.390, demonstrating superior capability in capturing sparse emboli. In contrast, deep learning models such as Xception with SGDM optimization performed poorly in this subgroup (e.g., IoU = 0.052, Dice = 0.076, F1 = 0.076), highlighting the difficulty in detecting very small emboli using standard architectures.

In the intermediate embolization range (0.0001–0.001), segmentation accuracy improved across all models. CIOF remained top performance (IoU = 0.662, Dice = 0.784), followed by InceptionResNetV2 with SGDM (IoU = 0.598, Dice = 0.725). ResNet50 with SGDM and MobileNetV2 with ADAM also showed competitive performance, with F1-scores exceeding 0.600.

For cases with larger embolic regions (>0.001), all models achieved higher performance. CIOF again yielded the highest metrics (IoU = 0.796, Dice = 0.884), while InceptionResNetV2 + SGDM and ResNet50 + SGDM followed closely with Dice scores of 0.862 and 0.840, respectively.

Segmentation performance correlated strongly with embolization size. Smaller emboli remained a key challenge for all models except CIOF, emphasizing the need for enhanced sensitivity in low-contrast and low-volume scenarios.

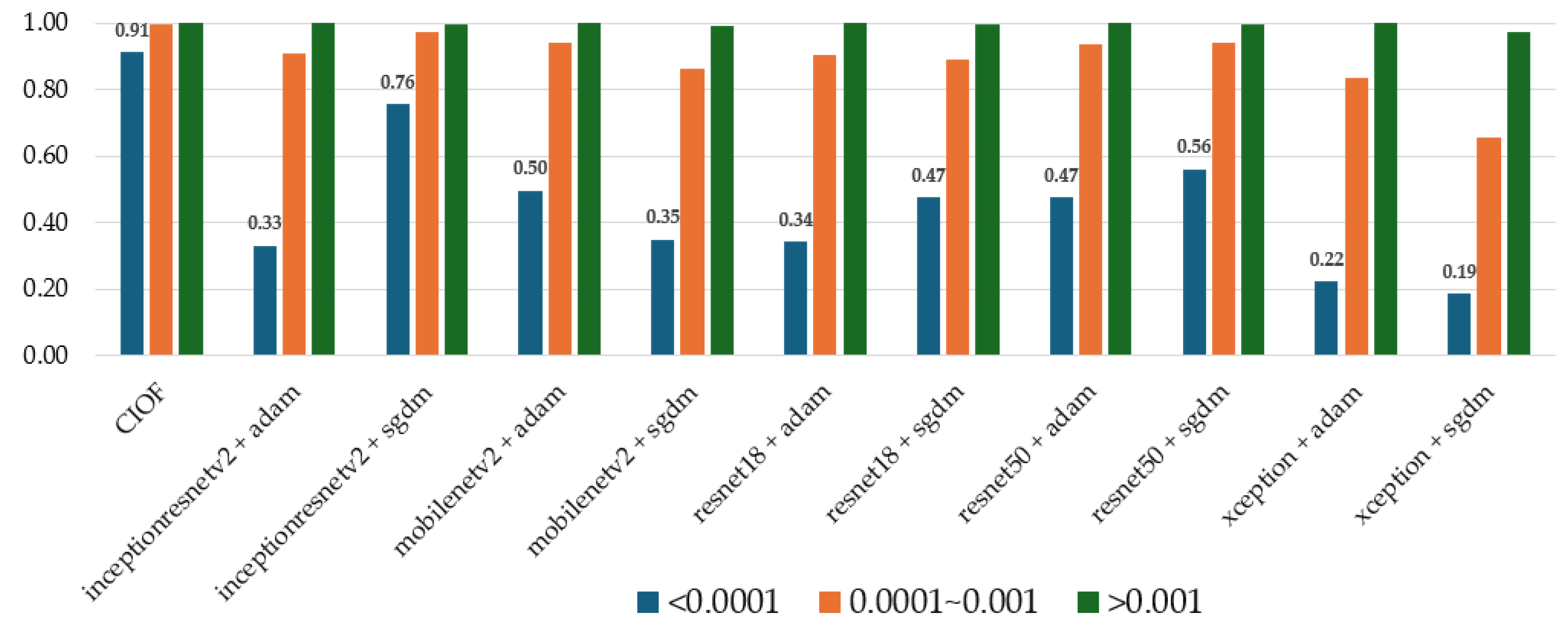

4.2. The Impact of Clinical Applications by Using CIFO

To evaluate the effectiveness of different models in detecting pulmonary embolism (PE) across varying embolization burdens, detection rates (P(IoU > 0)) were computed and stratified by embolization ratio in the images (<0.0001, 0.0001–0.001, and >0.001). As shown in

Table 3, the CIOF model significantly outperforms all tested deep learning models across all embolization ratios.

For images with small embolization areas (<0.0001), CIOF achieves a detection rate of 0.912, whereas the next best-performing deep model (InceptionResNetV2 + SGDM) reaches only 0.757. Most other models demonstrate poor sensitivity in this challenging category, with detection probabilities often falling below 0.5. This suggests that traditional CNN-based architecture, despite optimization, struggle to capture minimal embolic signals in CTA scans.

In the medium embolization range (0.0001–0.001), CIOF maintains near-perfect performance with 0.997 detection, closely followed by several deep models (e.g., ResNet50 + SGDM: 0.942 and MobileNetV2 + Adam: 0.941). Detection performance improves across all models in this range, but CIOF still provides the most robust and consistent detection.

For large embolization cases (>0.001), all models achieve near-perfect detection rates (typically ≥0.998), indicating that high clot burden is relatively easy to detect, regardless of architecture. Nevertheless, CIOF retains a slight advantage in reliability with 1.000 detection and 0.000 false negatives, which is critical in clinical decision-making.

CIOF offers consistently high sensitivity and negligible missed detections across all embolization scales, especially excelling in cases where deep learning models exhibit their greatest limitations. These results highlight the potential clinical utility of CIOF as a reliable screening tool for pulmonary embolism in CTA, particularly in subtle or early-stage presentations.

CIOF consistently achieves the highest detection rates across all embolization categories, notably maintaining high performance (0.91) even in the most challenging small embolization class (<0.0001) (

Figure 3). Deep learning models demonstrate strong performance in detecting large emboli (>0.001) but suffer from significant performance degradation when dealing with very small embolic regions. For instance, InceptionResNetV2 + Adam and Xception + SGDM yield detection probabilities of only 0.33 and 0.19, respectively, in the smallest embolization class. In contrast, InceptionResNetV2 + SGDM and ResNet50 + SGDM show relatively better robustness with detection rates of 0.76 and 0.56, respectively. These findings reinforce CIOF’s superior reliability in detecting emboli of all sizes, especially in clinically challenging scenarios with low embolic burden.

5. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5.1. Effectiveness of CIOF in Segmenting Small Pulmonary Emboli in CT Angiography

Small pulmonary emboli, particularly those occupying fewer than 26 pixels in CT angiography (CTA) images, are frequently located in the distal branches of the pulmonary arteries, including subsegmental or microvascular regions. Although these emboli contribute to a smaller overall clot burden, their detection remains clinically important due to several factors:

Early Diagnosis: Small emboli may represent early-stage pulmonary embolism, enabling preemptive intervention before progression to massive PE.

Clinical Risk in Vulnerable Patients: In patients with comorbidities (e.g., cancer, thrombophilia), even small emboli may lead to adverse outcomes due to impaired pulmonary perfusion.

Challenge for AI Models: Small emboli pose a technical challenge due to their low contrast, small size, and location in vessels close to image resolution limits. Models must exhibit high sensitivity and precise localization.

The detection performance for these cases, as shown in

Table 1, highlights the need for advanced fusion strategies like CIOF that reduce missed detections by enhancing model consensus.

Table 4 presents the absolute detection counts of pulmonary embolism (PE) across three stratified embolization ratios in CT images: low (<0.0001), medium (0.0001–0.001), and high (>0.001), comparing the performance of the CIOF framework against ten individual deep learning models. For each ratio category, the number of successfully segmented emboli (IoU > 0) and failed segmentations (IoU = 0) are reported.

The CIOF method exhibits superior robustness, detecting a total of 2,263 emboli with minimal failure cases (only 41 missing), outperforming all other models in both high and low embolization settings. In contrast, some individual models, particularly Xception + SGDM, show high miss rates (e.g., 847 missing cases), highlighting CIOF’s consistent accuracy even under challenging conditions such as small emboli or low contrast regions.

A single pixel in CTA typically represents 0.5–0.7 mm depending on resolution. Therefore, an embolus <26 pixels correspond to a clot size spanning ~13 mm², likely involving subsegmental or smaller branches (

Table 5). CIOF reduced the missed detection rate for these cases by harmonizing weak signals and compensating for model-specific blind spots.

This result underscores the utility of ensemble-based fusion strategies in handling the “long tail” of difficult cases—such as microvascular emboli—where both anatomical complexity and imaging constraints coexist. By increasing sensitivity without sacrificing specificity, CIOF provides a clinically promising path forward for integrating deep learning into AI-assisted radiology workflows.

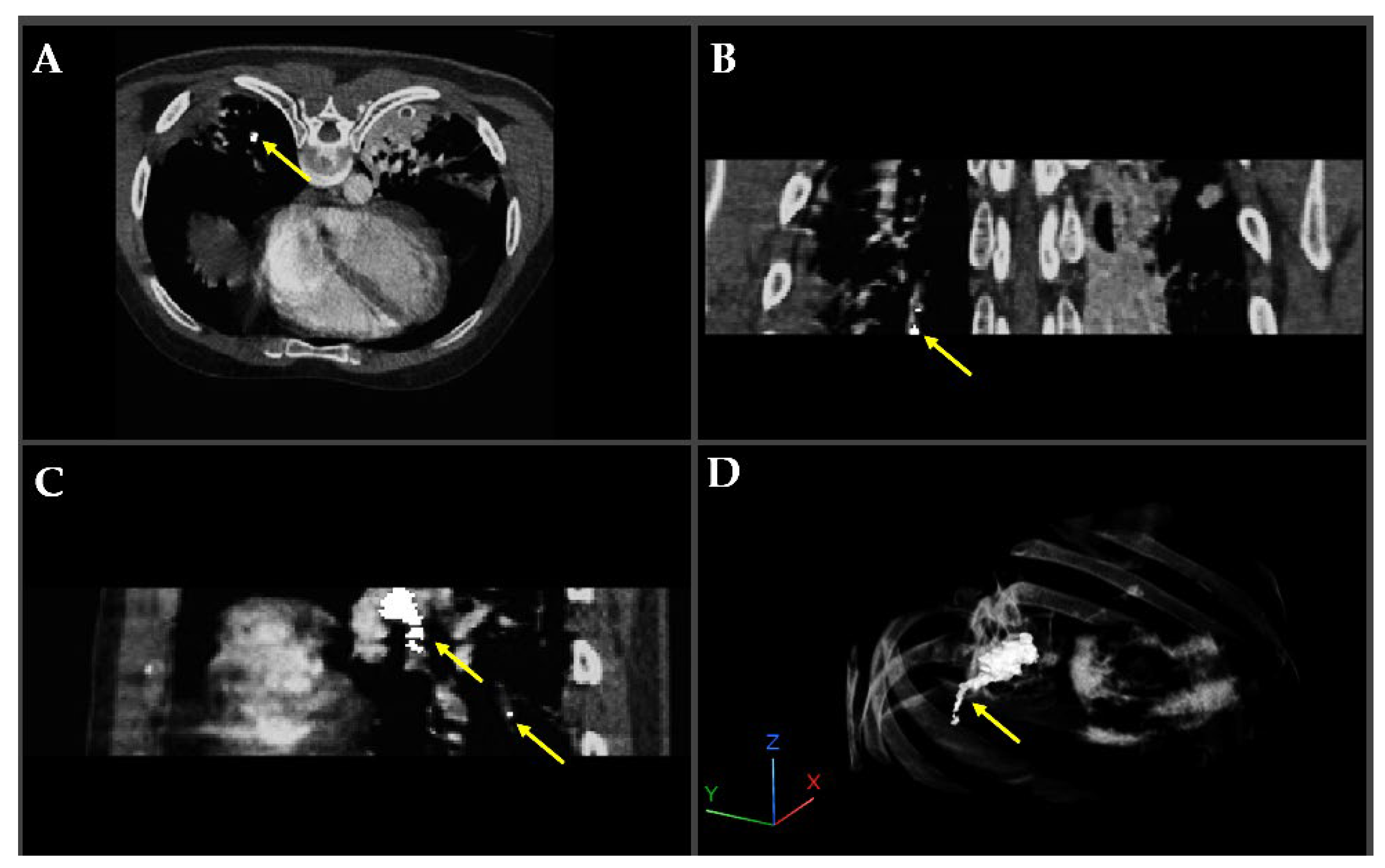

Figure 4 illustrates a pulmonary embolism (PE) detected in a patient’s CT angiography, shown across axial, coronal, sagittal, and 3D views. Yellow arrows highlight the embolus location within the pulmonary artery, demonstrating the value of multi-planar visualization in accurately assessing PE size and position.

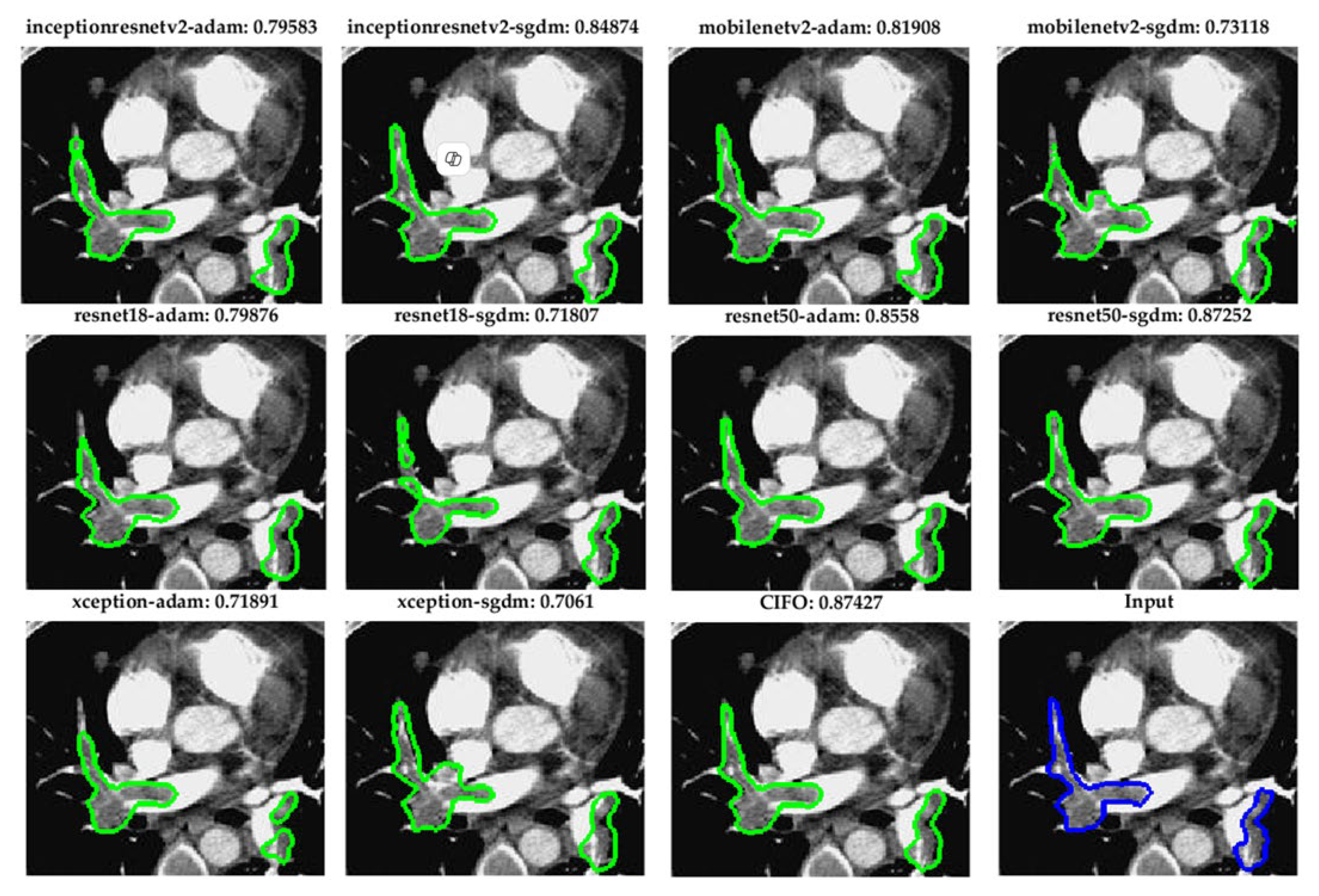

Figure 5. Visual comparison of pulmonary embolism (PE) segmentation results using ten fully convolutional network (FCN) models and the proposed CIOF fusion method. Each subfigure displays the segmented result (green contour) overlaid on a CT angiography slice, with the Dice coefficient shown above each result. The CIOF method demonstrates superior performance (Dice: 0.87427) compared to individual models. The original image and ground truth annotation (blue contour) are shown in the bottom-right panel for reference.

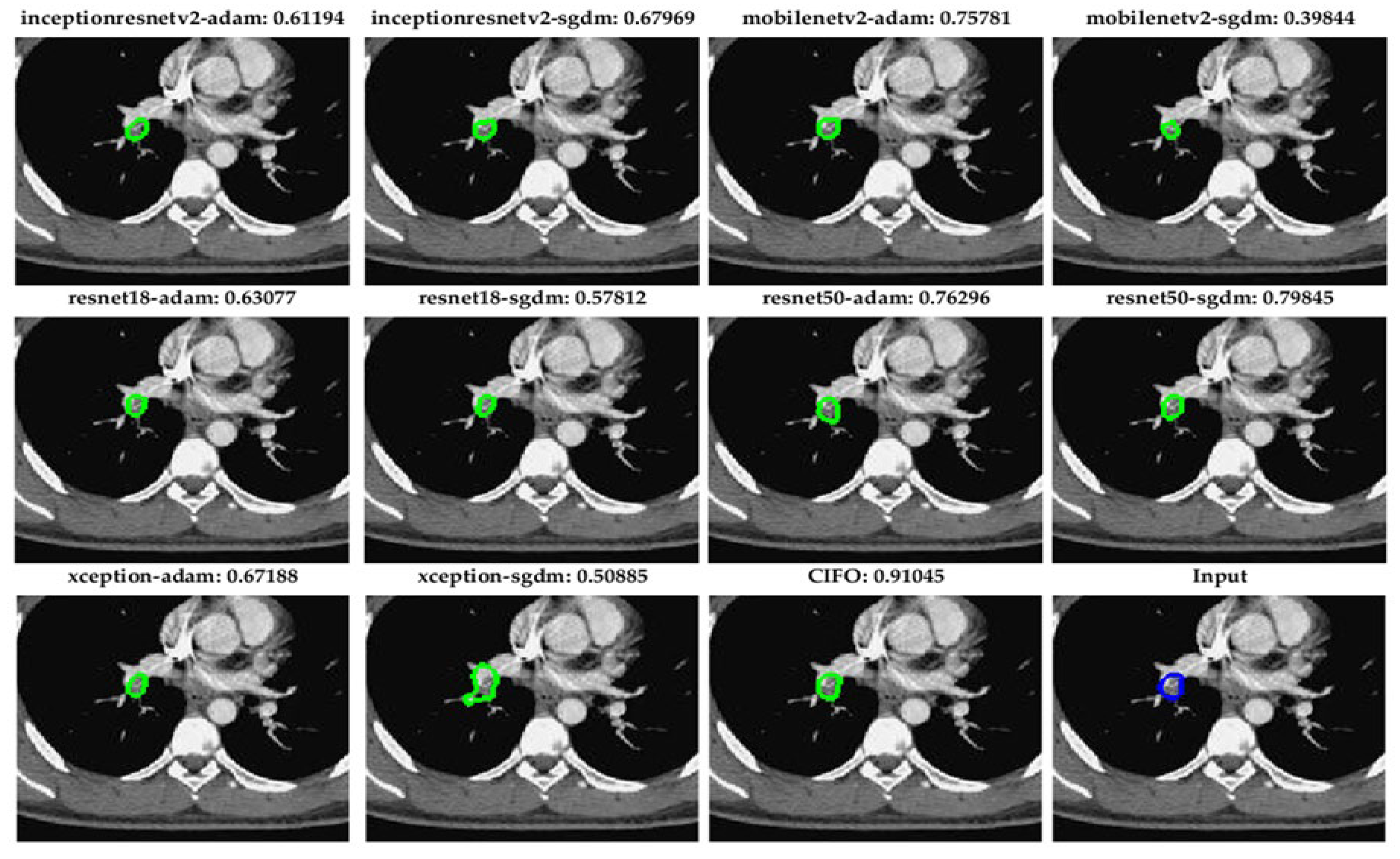

5.2. Robust Segmentation of Subsegmental Emboli with CIOF Fusion

Figure 6 demonstrates segmentation outcomes of small pulmonary emboli (<26 pixels) across ten fully convolutional network (FCN) configurations and the CIOF ensemble method. Each sub-image includes the original CTA slice with overlaid segmentation results. The Dice similarity score is displayed above each panel. The CIOF method demonstrates superior performance (Dice: 0.91045) compared to individual models. CIOF consistently provides a more accurate and complete delineation of emboli compared to individual models, especially in challenging small-vessel regions.

Accurate segmentation of small pulmonary emboli (<26 pixels) is crucial due to their clinical and technical significance. Clinically, these small emboli often reside in distal or subsegmental arteries, serving as early indicators of pulmonary embolism (PE) and enabling timely intervention to prevent progression and improve outcomes. Technically, their low contrast and limited size make them challenging to detect, often resulting in high false-negative rates in individual models. The proposed CIOF fusion method addresses these challenges by integrating outputs from multiple FCN models, enhancing consensus and robustness in identifying subtle embolic regions. This adaptive ensemble approach improves sensitivity and reliability, especially in small-vessel territories where traditional models may fail.

5.3. Comparative Evaluation of CIOF Against State-of-the-Art PE Segmentation Approaches

Table 6 presents a comparative analysis of pulmonary embolism (PE) segmentation methods utilizing deep learning, based on recent high-impact studies. Various architectures have been proposed, including CNNs, attention-guided frameworks, and multiscale 3D models. Among these, the Multiscale 3D DL [

6], TSNet [

5], and nnU-Net [

4] approaches achieved high Dice coefficients of 0.89, 0.88, and 0.90, respectively, each validated on large datasets (N > 1,000).

The proposed CIOF framework, which integrates predictions from 10 fully convolutional networks (FCNs), achieved a mean Dice score of 0.88 on a dataset of 2,304 cases selected with an embolization-to-image pixel ratio greater than 0.001, outperforming or matching the performance of several advanced models, including the 3D CNN [

9] and multitask deep learning approach [

10]. Compared to individual CNN-based methods—such as classifier-guided attention CNN [

3] or SPE-YOLO [

7]—CIOF provides consistent segmentation outcomes by leveraging ensemble diversity, enhancing robustness particularly in complex anatomical regions. The proposed CIOF stands out as a competitive and scalable ensemble method, offering segmentation performance on par with the most recent state-of-the-art techniques while maintaining strong generalization across a sizable dataset. This supports the viability of ensemble fusion strategies in improving the reliability of automated PE detection systems.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a novel ensemble framework, CIOF (Convolutional Integrated Output Fusion), designed to improve pulmonary embolism (PE) segmentation in CT angiography by aggregating predictions from 10 fully convolutional networks (FCNs). The CIOF model achieved a mean Dice score of 0.88 on a dataset of 2,304 images with an embolization-to-image pixel ratio greater than 0.001, matching or outperforming advanced approaches such as 3D CNN [

9] and multitask DL [

10].

Crucially, CIOF demonstrated exceptional detection performance, with an overall detection rate (IoU > 0) of 98.2% and only 1.8% missed detections, significantly outperforming individual models, especially in low embolization scenarios. For images with extremely sparse emboli (embolization ratio < 0.0001), CIOF maintained a leading detection rate of 91.2%, highlighting its robustness and sensitivity to small clot regions.

These results confirm the effectiveness of the CIOF approach in improving segmentation precision, especially for subtle and clinically challenging PE cases.

6. Limitations and Future Works

While the proposed CIOF framework demonstrates high segmentation accuracy and robust detection performance across various embolization levels, several limitations should be acknowledged.

First, the study was conducted using a single-center dataset of 2,304 CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) images, which may limit the generalizability of the results across institutions with different scanner types, imaging protocols, or population demographics. Second, although the ensemble approach effectively boosts performance, it also increases computational complexity and may hinder real-time deployment in clinical environments without GPU acceleration. Additionally, the method focuses on pixel-wise segmentation without integrating clinical context or anatomical landmarks, which could be beneficial for improving specificity and reducing false positives.

For future work, we plan to (1) validate the CIOF model on multi-center and multi-vendor datasets to ensure broader applicability, (2) investigate lightweight ensemble strategies or model distillation to reduce inference time, and (3) incorporate clinical metadata and anatomic priors to improve interpretability and diagnostic relevance. Further extension toward weakly-supervised and semi-supervised learning may also enhance performance where labeled data is scarce, particularly for small emboli cases.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, N.-H.L., Y.-H.H. and T.-B.C.; methodology, N.-H.L. and T.-B.C.; software, C.-Y.W., T.-B.C. and K.-Y.L.; validation, Y.-H.H. and K.-Y.L.; formal analysis, C.-Y.W., T.-B.C. and N.-H.L.; investigation, N.-H.L.; resources, N.-H.L.; data curation, C.-Y.W. and Y.-H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, N.-H.L.; writing—review and editing, N.-H.L. and T.-B.C.; visualization, T.-B.C.; supervision, T.-B.C.; project administration, N.-H.L.; funding acquisition, N.-H.L. and Y.-H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by EDA Hospital and National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, grant number EDCHP114003 and NSTC 113-2221-E-214-007.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to EDA Hospital and the National Science and Technology Council in Taiwan for their partial financial support under contracts No. EDCHP114003 and NSTC 113-2221-E-214-007. The authors would like to acknowledge AJE for the English editorial assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kahraman AT, Acar M, Uslu F, Şimşek C. Deep learning-based segmentation improves PE detection in CT angiography. Heliyon. 2024;10(19):e38118. [CrossRef]

- Djahnine A, Lazarus C, Lederlin M, Mulé S, Wiemker R, Si-Mohamed S, et al. Detection and severity quantification of pulmonary embolism with 3D CT data using an automated deep learning-based artificial solution. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2024;105:97–103. [CrossRef]

- Bushra F, Khan M, Shah PM, Ahmad Z, Khan F, Lee Y. A dual-pronged classifier-guided attention-based CNN framework for PE detection in CTA imaging. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;225:120207. [CrossRef]

- Lanza E, Khan M, Pontillo G, Gemignani F, Ulivi L, et al. nnU-Net-based deep learning for pulmonary embolism detection and clot volume measurement. Eur Radiol. 2024;34(9):5942–5950. [CrossRef]

- Fan J, Luan H, Qiao Y, Li Y, Ren Y, et al. Detection and segmentation of pulmonary embolism in 3D CTPA using a threshold adjustment segmentation network (TSNet). Sci Rep. 2025;15:7263. [CrossRef]

- Fan J, Luan H, Ren Y, et al. Multiscale integration in 3D deep learning for segmentation architectures: application to PE detection. Sci Rep. 2025;15:7285. [CrossRef]

- Wu H, Xu Q, He X, Xu H, Wang Y, Guo L. SPE-YOLO: A deep learning model focusing on small pulmonary embolism detection. Comput Biol Med. 2025;184:109402. [CrossRef]

- Wu H, Chen T, Wang L, Guo L. Speed and accuracy in tandem: deep learning-powered millisecond-level pulmonary embolism detection in CTA. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2025;106:107792. [CrossRef]

- Zhu H, Tao G, Jiang Y, et al. Automatic detection of pulmonary embolism on computed tomography pulmonary angiogram scan using a three-dimensional convolutional neural network. Eur J Radiol. 2024;177:111586. [CrossRef]

- Ma X, Zhou Z, Liang J. A multitask deep learning approach for PE detection and characterization with RV/LV ratio prediction. Sci Rep. 2022;12:8759. [CrossRef]

- Khan M, Shah PM, Khan IA, Islam SU, Ahmad Z, Khan F, Lee Y. IoMT-enabled computer-aided diagnosis of pulmonary embolism from computed tomography scans using deep learning. Sensors (Basel). 2023;23(3):1471. [CrossRef]

- Li L, Peng M, Zou Y, Li Y, Qiao P. The promise and limitations of artificial intelligence in CTPA-based pulmonary embolism detection. Front Med (Lausanne). 2025;12:1514931. [CrossRef]

- Doğan K, Yurt S, Giray B, Gökmen F, Akmansu Ç. An enhanced mask R-CNN approach for PE detection and segmentation in CT images. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14(11):1102. [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan-Balik Ü, Kandemir E, Ceylan E, Karadag M, Topçu S. Computer-aided detection for segmental and subsegmental PE: performance of deep ensemble systems. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(7):1150. [CrossRef]

- Hu Z, Wang T, Li Q, Zhao X, Yang L, et al. High performance with fewer labels using semi-weakly supervised learning for pulmonary embolism diagnosis. NPJ Digit Med. 2025;8:254. [CrossRef]

- Islam NU, Gehlot S, Zhou Z, Gotway MB, Liang J. Seeking an optimal ensemble approach for pulmonary embolism CAD across multiple datasets. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2024;104:102456. [CrossRef]

- Biret CB, Gurbuz S, Akbal E, et al. Advancing pulmonary embolism detection with integrated deep learning architectures. J Digit Imaging. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Islam NU, Zhou Z, Gehlot S, Gotway MB, Liang J. Seeking an optimal approach for computer-aided diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Med Image Anal. 2024;91:102988. [CrossRef]

- Abdulaal L, Maiter A, Salehi M, Sharkey M, Alnasser T, Garg P, et al. A systematic review of artificial intelligence tools for chronic pulmonary embolism on CT pulmonary angiography. Front Radiol. 2024;4:1335349. [CrossRef]

- Gao C, Zhang Z, Huang Y, Li Q. Deep learning in lung nodule detection and segmentation: a systematic review. Eur Radiol. 2025;35(1):112–124. [CrossRef]

- Lanza E, Ammirabile A, Francone M. Meta-analysis of AI-based pulmonary embolism detection: how reliable are deep learning models? Comput Biol Med. 2025;193:110402. [CrossRef]

- Fan J, Luan H, Qiao Y, Li Y, Ren Y, et al. TSNet segmentation network for pulmonary embolism in 3D CTPA. Sci Rep. 2025;15:7263. [CrossRef]

- Planquette B, Le Berre A, Khider L, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: deep learning supported analysis. Thromb Res. 2022;197:94–99. [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb M, Moyer E, Bernard K. Epidemiology of pulmonary embolism diagnosis and management among United States emergency departments over an eight-year period. Am J Emerg Med. 2024;85:158–162. [CrossRef]

- Ben Yehuda O, Itelman E, Vaisman A, Segal G, Lerner B. Early detection of pulmonary embolism in a general patient population immediately upon hospital admission using machine learning to identify new, unidentified risk factors: model development study. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26:e48595. [CrossRef]

- Hagen F, Vorberg L, Thamm F, et al. Improved detection of small pulmonary embolism on unenhanced computed tomography using an artificial intelligence-based algorithm—a single centre retrospective study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2024;40:2293–2304. [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo T, Barbera S, Ascenti V, Cicero G, Terrani S, Caruso D, Laghi A, Fontana F, Venturini M, Piacentino F, et al. Pulmonary embolism detection without intravenous contrast using electron density and Z-effective maps from dual-energy CT. Radiology Advances. 2024;1(3):umae025. [CrossRef]

- Huhtanen H, Nyman M, Mohsen T, Virkki A, Karlsson A, Hirvonen J, et al. Weakly-supervised InceptionResNetV2 + LSTM model for stack-wise PE detection in CT scans. BMC Med Imaging. 2022;22:43. [CrossRef]

- Pu J, Hu L, Chen W, Wang L, Wang J, Xu F, et al. Automated detection and segmentation of pulmonary embolisms on CTPA using deep learning without manual outlining. Med Image Anal. 2023;89:102882. [CrossRef]

- Sharkey MJ, Bustin A, Lau S, Simmons BD, Guleyupoglu Kini P. Fully automatic heart and great vessel segmentation on CTPA using deep learning. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:983859. [CrossRef]

- Weikert T, Winkel DJ, Bremerich J, Parmar V, Sauter AW, et al. Automated detection of pulmonary embolism in CT pulmonary angiograms using AI-powered algorithm: clinical validation results. Eur Radiol. 2023;33(5):2429–2437. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).