1. Introduction

Traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) has an incidence ranging from 3 to 196 per million worldwide [

1]. This condition predominantly impacts young adults, with an average age of 32 years, with a significant physical, emotional, and financial impact on patients and their families. Trauma is the most prevalent cause of SCI.

According to the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA), neurological impairments are categorized as follows: A (complete sensorimotor loss below the lesion), B (intact sensory but no motor function below the lesion), C (some motor function with most muscles graded below 3), and D (most muscles below the lesion graded at 3 or higher)[

2].

The trauma leads to tissue injury through two mechanisms: primary and secondary injury. Primary injury results from direct mechanical trauma to the spinal cord, causing bleeding, tissue compression, and necrosis [

3], which in turn leads to glial activation, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress in the spinal cord. The severity and outcome of a spinal cord injury (SCI) are largely determined by the extent of the primary injury.

The secondary injury originates from spinal cord oedema, which leads to spinal cord ischemia and injury [

4]. These events begin a few hours after trauma, and the condition is aggravated by involving the autonomous, system presenting with hypotension and therefore affecting neurons and glia and inducing necrosis and apoptosis [

5]. Apart from that, activated astrocytes release several factors, such as intermediate filaments, GFAP, nestin, and vimentin, which are contributing factors in glia scar formation [

6].

The spinal cord undergoes partial regeneration and recovery after injury, which is clinically not significant despite the spontaneous initiation of recovery [

7]. Early surgical decompression 24 hours post-injury is the most effective method to limit tissue damage following the primary injury [

8].

Despite extensive research efforts, effective treatment strategies for SCI remain elusive and challenging to implement. For example, while stem cell therapy has shown high potential for recovery after SCI, its clinical efficacy remains unclear, and the therapy faces several challenges before it can be fully implemented [

9,

10]. Therefore, it is crucial to elucidate the mechanisms by which therapies promote regeneration after SCI. Additionally, understanding how to modulate the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms in a coordinated manner is essential to developing effective therapies for SCI.

This review proposes a cell-based therapeutic protocol by focusing on the involved cellular mechanisms. This protocol is hypothesized and designed for testing in preclinical studies, with the potential for application in clinical trials.

2. Underlying Mechanism and Cellular and Molecular Pathways of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury

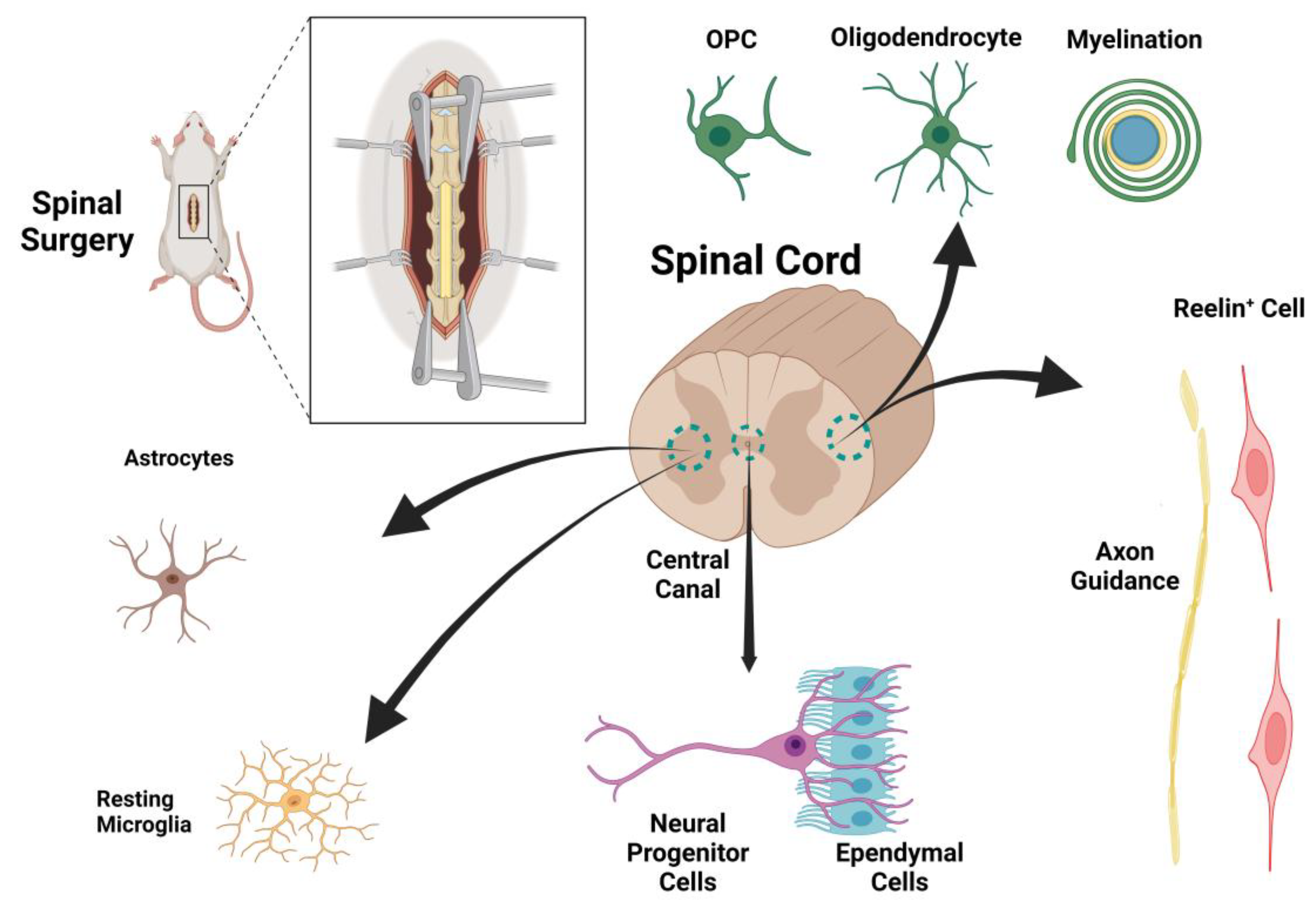

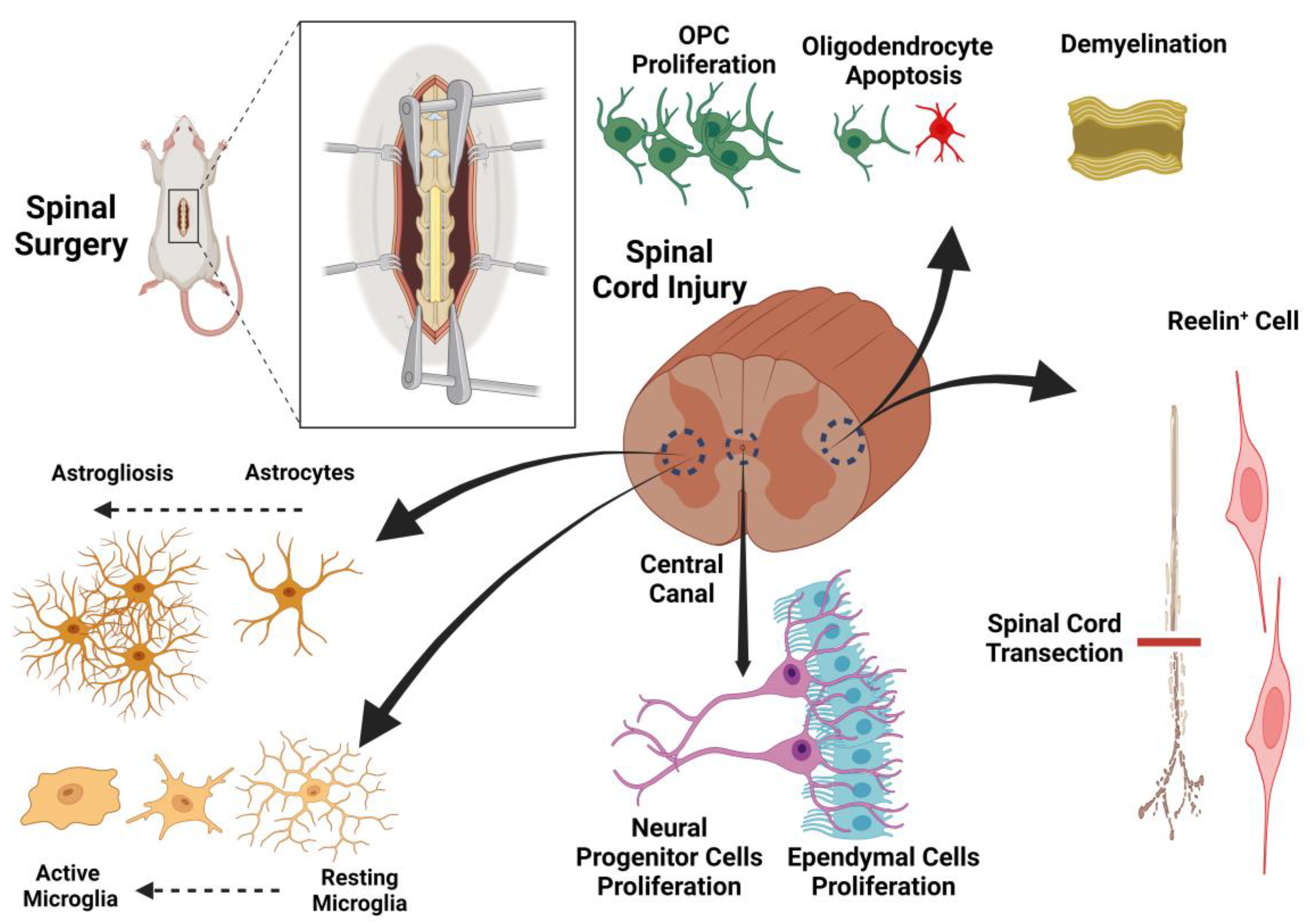

A therapeutic design based on the underlying mechanisms of spinal cord injury could potentially identify targets for effective treatment. As previously mentioned, both direct trauma and secondary edema associated with tissue ischemia play important roles in spinal cord injuries. We begin by elucidating the main cellular and molecular pathways leading to tissue injury and then, in a stepwise manner, present our suggested therapeutic protocol. While the list of factors contributing to regeneration after SCI is extensive, we have chosen to focus on pathways that are therapeutically targetable in our proposed protocol for SCI recovery. Among the various cell types in the spinal cord with potential for regeneration after spinal cord injury, astrocytes, Reelin

+ cells, and oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) appear to be promising targets for therapy. However, the roles of other cell types, such as progenitor cells, ependymal cells, oligodendrocytes, and microglia, will also be discussed (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

3. Astrocytes: Their Roles in Injury Response, Reprogramming, and Synaptic Regulation

Astrocytes are the most abundant type of glial cell in the CNS and play multifaceted roles in both health and disease. Under normal conditions, astrocytes support neuronal metabolism, maintain extracellular ion balance, regulate neurotransmitter uptake, and contribute to the formation and maintenance of the blood-brain barrier. In response to CNS injury, astrocytes undergo morphological and functional changes, becoming reactive astrocytes that proliferate and form glial scars (

Figure 2). While the glial scar serves to contain injury and limit the spread of inflammation, its pathophysiological function ultimately inhibits axonal regeneration and impedes functional recovery by creating a physical and biochemical barrier to axonal growth. Astrocytes also exhibit remarkable plasticity. They have the potential to convert into neurons through a two-step process: first transforming into neuroblasts and then into mature neurons [

11]. This phenomenon is called astrocyte reprogramming [

12,

13], has been demonstrated not only in the brain but also in the spinal cord [

14,

15]. The efficiency of astrocyte-to-neuron conversion is influenced by the local microenvironment, signaling molecules, and the intrinsic gene expression profile of astrocytes. Beyond their role in injury and regeneration, astrocytes are essential for synapse homeostasis and actively modulate synaptic activity [

16]. They participate in the tripartite synapse, responding to and regulating neurotransmitter release, synaptic strength, and plasticity. Astrocytic gene expression is dynamically regulated by synaptic activity, primarily through cAMP–PKA signaling pathways [

17]. This has led researchers to investigate small molecules such as cAMP and its stimulator Rolipram (a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor) for their effects on astrocyte reprogramming and neuronal transformation. These interventions induce the expression of neuronal markers [

18], promote neurite outgrowth, and alter astrocyte morphology [

19]. Moreover, increased cAMP levels drive actin polymerization, resulting in actin cytoskeleton remodeling of astrocytes [

20], which is crucial for changes in cell shape and motility. Astrocytes also play a key role in neuroinflammation; proinflammatory cytokine release is regulated by the cAMP pathway. Analogs of cAMP can reduce the release of proinflammatory cytokines and TNFα from astrocytes [

19], conferring a neuroprotective effect [

21]. Dysregulation of these processes has been implicated in a variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders, highlighting astrocytes as potential therapeutic targets for modulating neuroinflammation, promoting regeneration, and restoring synaptic function.

Astrocyte reprogramming into neurons across different CNS regions involves a complex interplay of molecular mechanisms, and these mechanisms can vary depending on the local environment and astrocyte subtype in each region. There are several molecular mechanisms underlying astrocyte reprogramming. For example, the alteration in expression of transcription factors (TFs) such as Ascl1, NeuroD1, Ngn2, and Brn2 can directly reprogram astrocytes into neurons both in vitro and in vivo [

22,

23]. The efficacy and outcome of TF-mediated reprogramming can differ by CNS region due to the intrinsic molecular diversity of astrocytes. For example, astrocytes in the cortex, hippocampus, and striatum express distinct sets of genes and respond differently to reprogramming cues. Apart from that, regional heterogeneity in astrocyte gene expression and function (e.g., glucose and potassium homeostasis, synaptic regulation) influences their responsiveness to reprogramming factors [

24].

4. Reelin+ Cells: Key Roles in Extracellular Matrix Formation and Neuronal Migration

The next candidate cell type is reelin

+ cells, which are defined by their secretion of the large extracellular matrix glycoprotein Reelin. Reelin is a master regulator of neuronal migration during development, particularly within the neocortex, where it acts as a stop signal for radially migrating neurons, ensuring the correct “inside-out” patterning of cortical layers [

25]. Reelin’s complex structure featuring an N-terminal region, eight epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like repeats, and a highly conserved C-terminal domain enables its dual roles in extracellular matrix organization and cellular signalling [

26]. This process is mediated through the binding of Reelin to the very low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) and apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2), which triggers phosphorylation of the intracellular adaptor protein Dab1 and subsequent cytoskeletal reorganization [

27,

28]. In the spinal cord, Reelin mRNA expression is found in both ventral and intermediate regions, where it provides positional information that guides the migration of preganglionic neurons [

29]. However, this regulatory function of Reelin is limited to radial migration, as other types of migration, such as tangential migration and the dorsally directed movement of preganglionic neurons, are not affected in the absence of reelin secretion [

29]. Beyond its role in migration, Reelin in connection with netrin-1 guides commissural axons. While netrin-1 attracts axons toward the midline, Reelin stabilizes their trajectory post-crossing, preventing aberrant recrossing and ensuring proper circuit formation [

30,

31]. This networking is essential for the establishment of functional neural networks throughout the central nervous system.

At the behavioral level, Reelin deficiency disrupts limb coordination by desynchronizing lumbar and cervical central pattern generators, resulting in symptoms such as ataxia, weakness, and muscle paralysis, which are reminiscent of those observed in reeler mutant animals [

26,

32]. Therefore, reelin could be considered part of therapeutic strategies for treating movement complications after spinal cord injury. Reelin’s influence extends well beyond development. In the adult brain, Reelin enhances synaptic plasticity by modulating NMDA receptor function and promoting dendritic spine maturation, thereby facilitating long-term potentiation and supporting learning and memory processes [

33]. Dysregulation of Reelin signaling is implicated in a range of neurological and psychiatric disorders. For example, reduced Reelin expression has been associated with synaptic deficits in autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia [

34]. The therapeutic potential of Reelin is considered by its ability to promote neural repair following injury. Reelin signaling reduces glutamate excitotoxicity through Disabled-1 (Dab1)/PI3K-dependent pathways [

35] and enhances axon regeneration in models of spinal cord injury [

36].

In summary, Reelin+ cells are critical for extracellular matrix formation, neuronal migration, and synaptic function throughout development and adulthood. Their dysfunction is implicated in a spectrum of neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders, and targeting Reelin signaling offers promising avenues for therapeutic intervention.

5. Ependymal Cells and Neural Progenitors: Challenges and Potential in Spinal Cord Injury Repair

The ependymal canal, lining the central canal of the spinal cord, includes critical cell populations for neural repair. Ependymal cells (Foxj1

+) function as neural stem cells (NSCs) and generate astrocytes and oligodendrocytes after SCI [

37]. These astrocytes are involved in glial scar formation, a major barrier to regeneration, after spinal cord injury in adulthood. However, Nestin-positive progenitor cells reside in the central canal, alongside NG2+ glial progenitors and Olig2

+ oligodendrocyte precursors in the surrounding ependymal zone [

38,

39].

The ependymal canal is the origin of tanycytes, a special type of ependymal cell that could serve as a source of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and regulate neurogenesis through morphogen signalling. Tanycytes and tanycyte-like ependymal cells in the central canal express neural stem cell markers and can generate astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in response to injury, indicating their potential as a regenerative factor [

40].

Neurogenesis occurs within a week after SCI, after which the generated cells can migrate to the site of injury. The BDNF/TrkB pathway modulates this neurogenic response, supporting NPC survival and differentiation [

41]. However, challenges remain in distinguishing the contributions of ependymal cells, NPCs, and infiltrating macrophages, as these populations may express overlapping markers and respond to similar environmental cues at the injury site. The lesion environment is further complicated by necrosis of cellular and extracellular matrix components, which can obscure the regenerative potential of endogenous progenitors [

42]. Age-related changes significantly affect the regenerative capacity of ependymal cells following spinal SCI. At birth, all spinal cord stem cell potential is localized within ependymal cells, but this capacity decreases over time. Juvenile ependymal cells exhibit a much higher intrinsic self-renewal ability compared to adult cells, both in uninjured states and after SCI. For example, in vitro and in vivo studies show that juvenile (P21) ependymal cells have a five-fold increase in self-renewal potential compared to adult cells following SCI, and this effect is transient, gradually disappearing with repeated cell passaging [

43]. Apart from that, as ependymal cells mature, their ability to proliferate and function as neural stem cells declines. Studies using single-cell analyses have identified a progressive increase in the fraction of mature ependymal cells with age, accompanied with a reduction in their stem-like and proliferative properties. This maturation process is dynamic and further limits the regenerative response to injury in older animals [

44,

45].

Clinical evidence indicates that spontaneous functional recovery after traumatic SCI is limited in mammals, with outcomes dominated by astrogliosis, scar formation, and persistent inflammation rather than regeneration [

46]. In contrast, regenerative models attributed to the ability of glial cells to adopt a pro-regenerative phenotype and avoid scar formation [

47]. These species also exhibit metabolic adaptations, such as hypoxia tolerance and lower succinate concentrations, which may mitigate inflammatory responses and promote tissue repair [

48] suggesting that metabolic differences lead to varied glial and immunologic responses in mammalian cell types, resulting in poor recovery and regeneration in the spinal cord after SCI. Despite the normal response of ependymal and NPC after SCI, recovery often results in astrogliosis, scar formation, PMN and macrophage infiltration, and necrosis rather than regeneration. This explains why regeneration does not occur immediately after SCI in mammals. The major targeted cells for treatment purposes are shown in

Figure 1.

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the development and maintenance of ependymal cells in the spinal cord. Wnt-responsive progenitor cells are restricted to the dorsal midline during development and give rise to dorsal ependymal cells in a spatially restricted pattern. In the postnatal and adult spinal cord, all ependymal cells express Wnt/β-catenin signaling components, and disruption of this pathway impairs ependymal cell proliferation, underscoring its continued importance for ependymal cell homeostasis [

49].

In summary, while the ependymal canal serves as a niche for neural progenitor cells with regenerative potential, the mammalian response to SCI is constrained by scar formation, inflammation, and metabolic limitations. Targeting signaling pathways such as Wnt and BDNF, or modulating the metabolic and immune milieu, may offer new strategies to enhance endogenous repair and functional recovery after SCI.

6. Role of Microglia in CNS Homeostasis and Spinal Cord Injury: Balancing Protection and Neurodegeneration

Microglia are highly specialized resident phagocytes of the central nervous system (CNS), acting as innate immune responders and essential regulators of neural development, homeostasis, and injury response. These cells, originally derived from yolk sac progenitors during embryogenesis, populate the CNS early in development and persist throughout life, continually surveying the microenvironment for signs of damage, infection, or dysfunction [

50]. In the healthy brain and spinal cord, microglia exist in a ramified, or surveying, state, dynamically interacting with neurons and synapses to support synaptic pruning, neurogenesis, and the refinement of neural circuits. Their activity is critical for maintaining neural plasticity and synaptic function, as well as for the removal of cellular debris and the clearance of apoptotic neurons during development [

51]. Upon spinal cord injury (SCI), microglia rapidly transition to an activated, amoeboid morphology and migrate to the site of injury, where they play a dual role in neuroprotection and neuroinflammation. In the acute phase following SCI, microglia are essential for limiting secondary damage by phagocytosing cellular debris, secreting neurotrophic factors, and modulating the activity of other glial cells. Early activation of microglia can help prevent excessive astrocytic scar formation, which is important for preserving tissue integrity and preventing further axonal degeneration [

52]. However, the beneficial effects of microglial activation are time-limited and context-dependent. Excessive or prolonged activation leads to the release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), which have potent neurotoxic effects and contribute to neuronal apoptosis, synaptic dysfunction, and neurodegeneration [

51,

52,

53,

54]. The interplay between microglia and infiltrating macrophages is a critical determinant of injury outcome. In the early stages following SCI, macrophages and microglia exhibit distinct but complementary roles. Macrophages, which are recruited from the circulation, inhibit the phagocytic activity of microglia, while microglia, in turn, induce the phagocytic activity of macrophages, creating a dynamic balance that helps to clear debris and limit inflammation. However, after the first week post-injury, this balance shifts toward a more pronounced proinflammatory state, characterized by increased phagocytic activity in both cell types and increased production of cytokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS). This transition is associated with the onset of secondary injury processes, including oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, and the activation of cell death pathways, which collectively exacerbate tissue damage and impair functional recovery [

51,

52,

53,

54].

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of microglial polarization in determining the outcome of SCI. Microglia can adopt either a proinflammatory (M1) or an anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotype, depending on the local microenvironment and the timing of injury. In the acute phase, M2 microglia predominate and contribute to tissue repair by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10, transforming growth factor-β [TGF-β]) and promoting the clearance of apoptotic cells [

54,

55]. However, as the injury progresses, the balance shifts toward the M1 phenotype, which is characterized by the production of proinflammatory mediators and the induction of cytotoxic pathways. This phenotypic switch is a key factor in the transition from neuroprotection to neurodegeneration and is influenced by a variety of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including aging, metabolic state, and the presence of systemic inflammation [

50,

56].

Emerging evidence also suggests that microglia play a role in modulating the activity of other glial cells, such as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, during SCI. Microglia-derived signals can influence astrocyte reactivity and the formation of the glial scar, which is a major barrier to axonal regeneration. While the glial scar is essential for limiting the lesion and preventing the spread of inflammation, excessive scar formation can delay axonal growth and functional recovery [

54,

57]. Microglia also interact with oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) to regulate remyelination, although the precise mechanisms underlying these interactions remain an active area of investigation [

58].

In summary, microglia are central players in the maintenance of CNS homeostasis and the response to SCI. Their ability to transition between protective and proinflammatory states is critical for proper injury response, but dysregulation of this balance can lead to chronic inflammation and neurodegeneration. Understanding the molecular and cellular mechanisms that govern microglial activation and polarization is essential for the development of targeted therapies aimed at promoting neuroprotection and functional recovery after SCI.

7. Role of Stem Cell Therapy in Spinal Cord Injury

Despite significant advances in regenerative medicine, stem cell therapy has not yet resulted in any approved treatment for spinal cord injury (SCI) [

59]. The translation of stem cell approaches into effective therapies for SCI remains limited, largely because the progression of SCI and its response to treatment depend on a complex interplay of molecular and cellular mechanisms that are not yet fully understood. One area of active research focuses on the activation of endogenous neural stem cells (NSCs) following injury. After SCI, endogenous NSCs residing in the spinal cord’s ependymal zone become activated, leading to their proliferation and migration towards the injury site. This response is regulated by multiple signaling pathways, including Notch, Wnt, and Sonic Hedgehog, and is supported by the local release of growth factors such as BDNF, NGF, and FGF. These processes collectively contribute to remyelination and limited neural regeneration, although endogenous repair alone is generally insufficient to restore function due to inhibitory factors in the injury environment, such as glial scar formation and chronic inflammation. In addition to endogenous repair, transplantation of exogenous stem cells has been explored as a strategy to enhance regeneration. Several cell sources have been investigated for this purpose. Adult NSCs can be harvested from regions such as the periventricular zone of the midbrain and transplanted into injured spinal cord tissue in animal models, where they have shown some capacity to differentiate and integrate. Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) offer pluripotency and the potential to generate a wide range of neural cell types, but their clinical use is limited by ethical concerns and the risk of immune rejection. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which are generated by reprogramming somatic cells, represent a promising alternative [

60]. iPSCs can be derived from the patient, reducing immunological barriers, and have demonstrated the ability to differentiate into neural lineages and support functional recovery in preclinical SCI models. Collectively, studies using these various cell types in animal models have demonstrated improvements in locomotor function, remyelination, and axonal regeneration, although the degree of benefit varies depending on the cell type, transplantation technique, and number of cells delivered. Furthermore, combining stem cell transplantation with biomaterial scaffolds or neurotrophic factor delivery can enhance cell survival and integration, suggesting that multimodal approaches may be necessary for optimal repair [

61,

62].

Despite these promising preclinical results, clinical translation faces several challenges. Immunological compatibility, the hostile post-injury microenvironment, risk of tumorigenicity (especially with pluripotent cells), and variability in patient response all present significant barriers. There is a need for improved patient selection criteria, refinement of cell sources and transplantation protocols, and the development of combinatorial therapies that address both cellular replacement and the modulation of the injury environment.

In conclusion, while stem cell therapy offers considerable promise for SCI repair, its clinical application requires further research to optimize cell sources, delivery methods, and patient selection. Integrating stem cell transplantation with other regenerative strategies and rigorous clinical trial design will be essential to realize the full therapeutic potential of this approach [

59,

63]

8. Conclusions

In summary, spinal cord injury remains one of the most complex and challenging neurological conditions to treat, due to the multifaceted cellular and molecular disruptions it induces. By combining pharmacological agents and targeting endogenous cell populations, it is possible to bridge the gap between injury stabilization and functional regeneration. Ultimately, targeting multiple regenerative pathways simultaneously may pave the way for more effective interventions and improved outcomes for individuals living with SCI.

Author Contributions

The Conceptualization, writing original draft were performed by all authors. Review and editing (constructive comments) are done by all authors. All authors approved final version of manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council (2023-02602) and Lundbeck Foundation (R322-2019-2721).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Jazayeri, S.B., et al., Incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury worldwide: A systematic review, data integration, and update. World neurosurgery: X, 2023: p. 100171. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.T., G.R. Leonard, and D.J. Cepela, Classifications In Brief: American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2017. 475(5): p. 1499-1504. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A., S.M. Dyck, and S. Karimi-Abdolrezaee, Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: An Overview of Pathophysiology, Models and Acute Injury Mechanisms. Front Neurol, 2019. 10: p. 282. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.W. and C. Sadowsky, Spinal-cord injury. The Lancet, 2002. 359(9304): p. 417-425.

- Wang, Z., et al., C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) mediates neuronal apoptosis in rats with spinal cord injury. Exp Ther Med, 2013. 5(1): p. 107-111. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.P., et al., Astroglial reaction in the gray matter lumbar segments after midthoracic transection of the adult rat spinal cord. Exp Neurol, 1981. 73(2): p. 365-77. [CrossRef]

- Barbiellini Amidei, C., et al., Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury: a large population-based study. Spinal Cord, 2022. 60(9): p. 812-819. [CrossRef]

- Fehlings, M.G., et al., Early versus delayed decompression for traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: results of the Surgical Timing in Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study (STASCIS). PLoS One, 2012. 7(2): p. e32037. [CrossRef]

- Gazdic, M., et al., Stem cells therapy for spinal cord injury. International journal of molecular sciences, 2018. 19(4): p. 1039.

- Szymoniuk, M., et al., Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Application of Multipotent Stem Cells for Spinal Cord Injury. Cells, 2023. 12(1): p. 120. [CrossRef]

- Niu, W., et al., In vivo reprogramming of astrocytes to neuroblasts in the adult brain. Nat Cell Biol, 2013. 15(10): p. 1164-75. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, B.B., A. Bhutani, and C.M. Stary, Adult neurogenesis from reprogrammed astrocytes. Neural Regen Res, 2020. 15(6): p. 973-979. [CrossRef]

- Seri, B., et al., Astrocytes give rise to new neurons in the adult mammalian hippocampus. J Neurosci, 2001. 21(18): p. 7153-60. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, B.B., A. Bhutani, and C.M. Stary, Adult neurogenesis from reprogrammed astrocytes. Neural Regeneration Research, 2020. 15(6): p. 973. [CrossRef]

- Su, Z., et al., In vivo conversion of astrocytes to neurons in the injured adult spinal cord. Nature communications, 2014. 5(1): p. 3338. [CrossRef]

- Shan, L., et al., Astrocyte-Neuron Signaling in Synaptogenesis. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2021. 9: p. 680301. [CrossRef]

- Hasel, P., et al., Neurons and neuronal activity control gene expression in astrocytes to regulate their development and metabolism. Nat Commun, 2017. 8: p. 15132. [CrossRef]

- Alexanian, A.R., Combination of the modulators of epigenetic machinery and specific cell signaling pathways as a promising approach for cell reprogramming. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 2022. 477(10): p. 2309-2317. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z., Y. Ikegaya, and R. Koyama, The astrocytic cAMP pathway in health and disease. International journal of molecular sciences, 2019. 20(3): p. 779. [CrossRef]

- Duggirala, A., et al., cAMP-induced actin cytoskeleton remodelling inhibits MKL1-dependent expression of the chemotactic and pro-proliferative factor, CCN1. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology, 2015. 79: p. 157-168. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.-L., et al., The protective effect of the PDE-4 inhibitor rolipram on intracerebral haemorrhage is associated with the cAMP/AMPK/SIRT1 pathway. Scientific Reports, 2021. 11(1): p. 19737. [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z., et al., Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Ascl1-Mediated Astrocyte-to-Neuron Conversion. Stem Cell Reports, 2021. 16(3): p. 534-547. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., In vivo Direct Conversion of Astrocytes to Neurons Maybe a Potential Alternative Strategy for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci, 2021. 13: p. 689276. [CrossRef]

- Endo, F., et al., Molecular basis of astrocyte diversity and morphology across the CNS in health and disease. Science, 2022. 378(6619): p. eadc9020. [CrossRef]

- Frotscher, M., Role for Reelin in stabilizing cortical architecture. Trends Neurosci, 2010. 33(9): p. 407-14. [CrossRef]

- D’Arcangelo, G., et al., A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature, 1995. 374(6524): p. 719-23. [CrossRef]

- D’Arcangelo, G., et al., Reelin is a ligand for lipoprotein receptors. Neuron, 1999. 24(2): p. 471-479. [CrossRef]

- Leeb, C., C. Eresheim, and J. Nimpf, Clusterin Is a Ligand for Apolipoprotein E Receptor 2 (ApoER2) and Very Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor (VLDLR) and Signals via the Reelin-signaling Pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2014. 289(7): p. 4161-4172. [CrossRef]

- Phelps, P.E., et al., Evidence for a cell-specific action of Reelin in the spinal cord. Dev Biol, 2002. 244(1): p. 180-98. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Sanz, C., et al., Cajal-Retzius cells instruct neuronal migration by coincidence signaling between secreted and contact-dependent guidance cues. Neuron, 2013. 79(3): p. 461-477. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., et al., Slit/Robo signals prevent spinal motor neuron emigration by organizing the spinal cord basement membrane. Dev Biol, 2019. 455(2): p. 449-457. [CrossRef]

- Brockett, E.G., et al., Ascending and Descending Propriospinal Pathways between Lumbar and Cervical Segments in the Rat: Evidence for a Substantial Ascending Excitatory Pathway. Neuroscience, 2013. 240: p. 83-97. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.T., et al., Reelin supplementation enhances cognitive ability, synaptic plasticity, and dendritic spine density. Learn Mem, 2011. 18(9): p. 558-64. [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, S.H., Reelin glycoprotein: structure, biology and roles in health and disease. Mol Psychiatry, 2005. 10(3): p. 251-7.

- Hiesberger, T., et al., Direct binding of Reelin to VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of disabled-1 and modulates tau phosphorylation. Neuron, 1999. 24(2): p. 481-9. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S., et al., Nerve regeneration restores supraspinal control of bladder function after complete spinal cord injury. J Neurosci, 2013. 33(26): p. 10591-606. [CrossRef]

- Barnabé-Heider, F., et al., Origin of new glial cells in intact and injured adult spinal cord. Cell stem cell, 2010. 7(4): p. 470-482. [CrossRef]

- Duan, H., et al., Endogenous neurogenesis in adult mammals after spinal cord injury. Science China Life Sciences, 2016. 59: p. 1313-1318. [CrossRef]

- Sabelstrom, H., et al., Resident neural stem cells restrict tissue damage and neuronal loss after spinal cord injury in mice. Science, 2013. 342(6158): p. 637-40. [CrossRef]

- Furube, E., et al., Neural stem cell phenotype of tanycyte-like ependymal cells in the circumventricular organs and central canal of adult mouse brain. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 2826. [CrossRef]

- Zholudeva, L.V., et al., Transplantation of Neural Progenitors and V2a Interneurons after Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma, 2018. 35(24): p. 2883-2903. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Barrera, R., et al., Neurogenesis after Spinal Cord Injury: State of the Art. Cells, 2021. 10(6): p. 1499. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., et al., Regenerative Potential of Ependymal Cells for Spinal Cord Injuries Over Time. EBioMedicine, 2016. 13: p. 55-65. [CrossRef]

- Albors, A.R., et al., An ependymal cell census identifies heterogeneous and ongoing cell maturation in the adult mouse spinal cord that changes dynamically on injury. Developmental Cell, 2023. 58(3): p. 239-+. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., et al., Characterizing progenitor cells in developing and injured spinal cord: Insights from single- nucleus transcriptomics and lineage tracing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2025. 122(2). [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.A., et al., From basics to clinical: a comprehensive review on spinal cord injury. Prog Neurobiol, 2014. 114: p. 25-57. [CrossRef]

- Ryczko, D., A. Simon, and A.J. Ijspeert, Walking with salamanders: from molecules to biorobotics. Trends in neurosciences, 2020. 43(11): p. 916-930. [CrossRef]

- Bundgaard, A., et al., Metabolic adaptations during extreme anoxia in the turtle heart and their implications for ischemia-reperfusion injury. Scientific Reports, 2019. 9(1): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Xing, L., et al., Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates ependymal cell development and adult homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2018. 115(26): p. E5954-E5962. [CrossRef]

- Prinz, M., et al., Microglia and Central Nervous System-Associated Macrophages-From Origin to Disease Modulation. Annu Rev Immunol, 2021. 39: p. 251-277. [CrossRef]

- Kolos, E.A. and D.E. Korzhevskii, Spinal Cord Microglia in Health and Disease. Acta Naturae, 2020. 12(1): p. 4-17.

- Gaudet, A.D. and L.K. Fonken, Glial Cells Shape Pathology and Repair After Spinal Cord Injury. Neurotherapeutics, 2018. 15(3): p. 554-577. [CrossRef]

- Brockie, S., J. Hong, and M.G. Fehlings, The Role of Microglia in Modulating Neuroinflammation after Spinal Cord Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021. 22(18): p. 9706. [CrossRef]

- Kroner, A. and J. Rosas Almanza, Role of microglia in spinal cord injury. Neurosci Lett, 2019. 709: p. 134370. [CrossRef]

- Kigerl, K.A., et al., Identification of Two Distinct Macrophage Subsets with Divergent Effects Causing either Neurotoxicity or Regeneration in the Injured Mouse Spinal Cord. Journal of Neuroscience, 2009. 29(43): p. 13435-13444. [CrossRef]

- Pottorf, T.S., et al., The Role of Microglia in Neuroinflammation of the Spinal Cord after Peripheral Nerve Injury. Cells, 2022. 11(13). [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.A., et al., Astrocyte scar formation aids central nervous system axon regeneration. Nature, 2016. 532(7598): p. 195-200. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A.F. and V.E. Miron, The pro-remyelination properties of microglia in the central nervous system. Nat Rev Neurol, 2019. 15(8): p. 447-458. [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.P., P.M. Warren, and J. Silver, The biology of regeneration failure and success after spinal cord injury. Physiological reviews, 2018. 98(2): p. 881-917. [CrossRef]

- Matiukhova, M., et al., A comprehensive analysis of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) production and applications. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2025. 13: p. 1593207. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Y. Luo, and S. Li, The roles of neural stem cells in myelin regeneration and repair therapy after spinal cord injury. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2024. 15(1): p. 204. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M., B. Borys, and S. Karimi-Abdolrezaee, Neural stem cell therapies for spinal cord injury repair: an update on recent preclinical and clinical advances. Brain, 2024. 147(3): p. 766-793. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.S., et al., Combinatorial therapies for spinal cord injury repair. Neural Regen Res, 2025. 20(5): p. 1293-1308. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).