1. Introduction

Castor (

Ricinus communis) oil is a platform chemical used in the industry for a variety of derivatives and products. Castor farming is transitioning to cropping systems based on large-scale production and mechanical harvest. A problem frequently observed on castor fields is the slow and uneven seedling emergence, which have considerable impact on the crop management and productivity [

1,

2]. In intensive cropping systems, even small gains in the time for emergence have significant impact on the final yield [

3].

Germination is a complex physiological process that consists on a sequence of events including water uptake, genes and enzyme activation, reserve mobilization, and cells growth and multiplication. The uneven germination of castor seed is caused by intrinsic characteristics of the seed and environmental factors such as salinity, temperature, morphology, and hormones [

1,

2,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. It can also be influenced by artificial procedures such as puncture on the seed coat, scarification, sorting by seed coat density, and ultrasound treatment [

2,

5,

15], and there was evidence that castor genotypes can be selected for fast germination [

4]. Interventions like mechanical breakage of the seed coat or scarification are effective for improving castor seed germination [

2,

5], but they are unpractical to be implemented in industrial seed production. There is some potential to explore seed priming, in which the seed is moisturized to induce the initial phases of germination, but the process is stopped before the radicle protrusion [

3,

8]. In castor and many other crops, this technique was effective to promote faster and more synchronized germination [

5,

8].

In addition to the slow emergence, there is some concern on the occurrence of volunteer castor plants on the following cropping season as this problem is also related to the process of seed dormancy and germination. Castor plants evolved to be dispersed by ants, and castor seeds are able to remain dormant in the soil for years waiting to germinate after a soil disturbance [

2,

16,

17]. While this behavior is an effective mechanism for seed dispersion and survival of wild castor plants, it needs to be elucidated and suppressed because it is a relevant problem for cropping castor fields in large-scale.

This series of experiments was performed with the objective to elucidate key aspects of castor seed germination and emergence and to prospect options on how to manipulate this physiological process searching for improved emergence. The research questions were:

(a) if the direction that the seed lays in the soil influences the time for emergence;

(b) if the seed treatment with gibberellin can be made many days before sowing;

(c) if gibberellin alleviates the suppressive effect of sub-optimal temperature;

(d) if castor seed can be pre-germinated aiming fast-emergence;

(e) if a high dose of gibberellin may cause detrimental effects on seed germination;

(f) if gibberellin applied on the seed has residual effect on the seedling;

(g) if the dormancy occurring after harvest reduces along the storage time;

(h) if the treatment with gibberellin is effective at field conditions;

(i) how lines selected in vitro for fast germination perform at field conditions, and

(j) if ungerminated castor seeds germinate after a soil disturbance.

2. Material and Methods

The experiments are not presented in the chronological order in which they were performed. Some experiments were designed considering the results previously obtained in other tests. Hybrid F2 seeds were used when the treatments required a short time between harvesting and planting. Different varieties were randomly adopted among the experiments aiming genetic diversity.

2.1. Seed direction influencing the time for germination

Castor seed cv. Tamar (F1 hybrid) were sown in plastic trays (length: 48 cm, width: 30 cm, depth: 11 cm) filled with a mix of soil and carbonized rice husks in the proportion of 1:1 (v:v). Six trays were partially filled with the substrate, the surface was leveled, and castor seeds were sown in five directions (

Table 1). After sowing, the seeds were covered with 4 cm of the same substrate with care for keeping the seed in the intended direction. The substrate was immediately irrigated, and the trays were kept in a greenhouse, under daily irrigation with an automatic sprinkler system.

The experiment followed a randomized complete block design with 5 treatments and 12 replications. Each tray was divided in two blocks, and each block consisted of five parallel rows (experimental units). Five castor seeds were sown in each row according to the treatment. Based on experience from previous experiments, the seedling could be clearly associated with its treatment according to its position on the tray. The emergence of castor seedlings was daily monitored up to 30 days after sowing. After the emergence was registered, the seedling was cut and discarded. The emergence rate at 6, 12, and 30 days after sowing were subjected to analysis of variance and test of Tukey (p < 0.05) for comparison of the treatments. The daily progress of emergence rate up to 30 days after sowing was presented in graphs.

2.2. Persistence of gibberellin effect with an interval from seed treatment to sowing

This experiment was made using hybrid F2 castor seeds cv. RS Otto 1, harvested in a commercial farm in Campo Novo do Parecis, MT, Brazil and stored for 4 months in a paper bag at room temperature. The treatments were periods from 0 and 9 days (one-day increments) between seed treatment and sowing. The hormone (ProGibb 400®) was applied in the dose of 400 mg of gibberellin, diluted in 45 mL of water, for 1 kg of castor seed. The solution was applied to the seed, mixed for spreading the solution on the seed surface, placed on a paper towel to dry for 24 h at room temperature, and stored in paper bags. The seed treatment was applied at different days, and the sowing was made at the same time. For the treatment 0 days, gibberellin was applied a few minutes before sowing.

The seed was sown in plastic trays and substrate as described in the

Section 2.1. The experiment followed a randomized complete block design with 10 treatments and 6 replications. Each tray corresponded to one block, and the ten experimental units were rows with 5 seeds (4-cm deep). After sowing, the substrate was immediately irrigated to full soil capacity, and kept moist with daily irrigations. The seedling emergence was made with the methods and period as described in the

Section 2.1. The seedling emergence was monitored daily up to 30 days after sowing. The emergence rate observed at 6 and 12 days after sowing was subjected to analysis of regression with the model

y = a

x + b, and the significance was tested (p < 0.05). The data on the emergence rate at 30 days after sowing was not subjected to regression analysis because it was just 0.4% higher than at 12 days after sowing.

2.3. Gibberellin influencing germination at suboptimal temperature

Castor seed cv. Tamar (hybrid F1), harvested two months before, were treated with increasing doses of gibberellin and incubated for germination at two temperatures. The six doses of the hormone were 0, 54, 108, 162, 216, and 270 mg of gibberellin (ProGibb 400®) diluted in 45 mL of water per kilogram of castor seed. The seed was moisturized with the hormone solution and left drying exposed to the air at room temperature for 5 days. Treated castor seeds were incubated in 12 germination boxes (11 x 11 cm) with two sheets of germination paper (230 g/m

2). Each germination box received 30 castor seeds treated with a dose of hormone according to the treatment and was incubated in the dark at either suboptimal (22 °C) or near-optimal (30 °C) temperatures [

5]. Seeds were carefully positioned with the caruncle downward (

Table 1, position 1). The germination paper was soaked with water (2.5x its weight), and more water was added during the experiment as needed to keep the seeds always covered with a thin film of water.

The seed was considered germinated after radicle protrusion (> 2 mm). Germinated seeds were daily counted and discarded up to 15 days of incubation. The accumulated germination rate (y) for each temperature after 5, 10, and 15 days of incubation was subjected to analysis of regression with the model y = ax + b, in function of the dose of gibberellin (x), and the significance was tested (p < 0.10).

2.4. Pre-germination and early seedling growth

This experiment evaluated if castor seed could be pre-germinated and oven dried at mild temperature before sowing, and if these treatments influence the seedling’s biomass accumulation. Castor seeds cv. Mia (hybrid F1) were exposed to the following treatments: (1) incubated to germinate with a solution of gibberellin (60 mg/L), (2) incubated to germinate with water, and (3) a control without pre-germination. The seed was incubated to pre-germinate for 39 h, at 30 °C, in trays with sheets of germination paper below and above the seed, and soaked with the hormone solution or water, according to the treatment. The amount of water or solution was not controlled in relation to the seed weight, but it aimed to keep the seed always covered with a thin film of water. The incubation time and temperature were defined in preliminary tests (not reported) aiming to avoid the seed to start radicle protrusion. After incubation, the seed was immediately oven dried at 45 °C for 24 hours. The seed moisture content before oven drying was 36.6% of its weight (dry base), on average of the two treatments. Considering the amount of water that the seed absorbed during the incubation, it was estimated that one kilogram of seed absorbed 22 mg of gibberellin, assuming that the seed coat was completely permeable to gibberellin. The seeds in the control treatment were not moisturized, incubated, nor exposed to the oven temperature.

Immediately after oven drying, the seeds were sown in plastic trays filled with substrate as described in the

Section 2.1. A grid with 45 squares was used for making 4-cm deep holes in nine trays, and one seed was sown in each hole. Following a completely randomized blocks design with nine replications, 15 seeds from each treatment were randomly assigned among the holes in each tray. Each emerging seedling could be clearly associated with its respective seed treatment.

The seedling emergence was daily registered, and the seedlings were allowed to continue growing. The experiment was terminated at 16 days after sowing. The shoot of the seedlings was cut, placed in paper bags, oven dried at 105 °C for 48 hours, and weighed. The emergence rate at the end of the experiment was subjected to analysis of variance and the means were compared by the test of Tukey (p < 0.05). The shoot dry weight of the castor seedlings (y) was subjected to analysis of regression with the days after emergence as the independent variable (x), using the exponential model y = y0 +a(1-ebx). The means of shoot dry weight from the three treatments were compared with test of Tukey (p < 0.05) only in the groups of seedlings with the ages of 4 and 8 days after emergence at harvest. That comparison had different number of replications for each treatment because the date of seedling emergence was not balance among the blocks.

2.5. Castor seed treated with high doses of gibberellin

This experiment evaluated the effect of gibberellin (ProGibb 400®) applied in doses exceeding the usual recommendations from previous experiments and from doses labeled for other crops. The study was made with hybrid F2 castor seeds cv. RS Otto 01 (as described in the

Section 2.2), harvested 2 months before. The seeds were treated with 10 doses of the hormone varying linearly from zero to 400 mg/kg. The hormone was diluted in water, in a volume equivalent to 45 mL per kilogram of castor seed. The seed treated with the dose 0 kg/ha received the same procedure using water. The solution was added to the seed, mixed for 1 minute, and allowed to dry exposed to the air at room temperature for 1 hour. The seed was sown in plastic trays, filled with the substrate as described in the

Section 2.1.

The experiment followed a randomized complete block design with 10 treatments and 6 replications. Each tray was a block, and the experimental plots were rows with five seeds. Seedling emergence was monitored daily, and the seedling was discarded just after its emergence was registered. The accumulated emergence rate (y) was subjected to analysis of regression with the model y = ax + b (p < 0.10), considering the dose of gibberellin as the independent variable (x). The analysis was made for the accumulated emergence observed at 6, 7, 8, and 30 days after sowing. The regression analysis was made on the data with replications, but for simplification, only the mean values were plotted in the graphs.

2.6. Residual effect of gibberellin influencing the initial plant growth

Castor seedlings are highly sensitive to gibberellin, as it promotes stem elongation when applied on the leaves [

18]. This experiment tested if the hormone applied on the seed carries some residual effect to the seedling’ stem elongation and biomass accumulation in the initial growth. The experiment used hybrid F2 castor seeds cv. RS Otto 01, harvested 6 months before (further details as described in the

Section 2.2). The seeds were treated with doses of gibberellin (ProGibb 400®) in 16 doses varying linearly from 0 to 400 mg/kg (0, 27, 53… 400 mg/kg). All the other procedures were made as described in the

Section 2.5, except that after the hormone treatment, the seed was allowed to dry at room temperature for 24 hours before sowing. Fifty seeds treated with each dose were sown in one tray filled with the same substrate as described in the section 2.1.

After emergence, the height of each individual plant was registered every day up to 13 days after sowing. The plant height was measured from the substrate surface to the internode between the cotyledon leaves.

Assuming that the stem elongation is strongly influenced by the shade from neighbor plants [

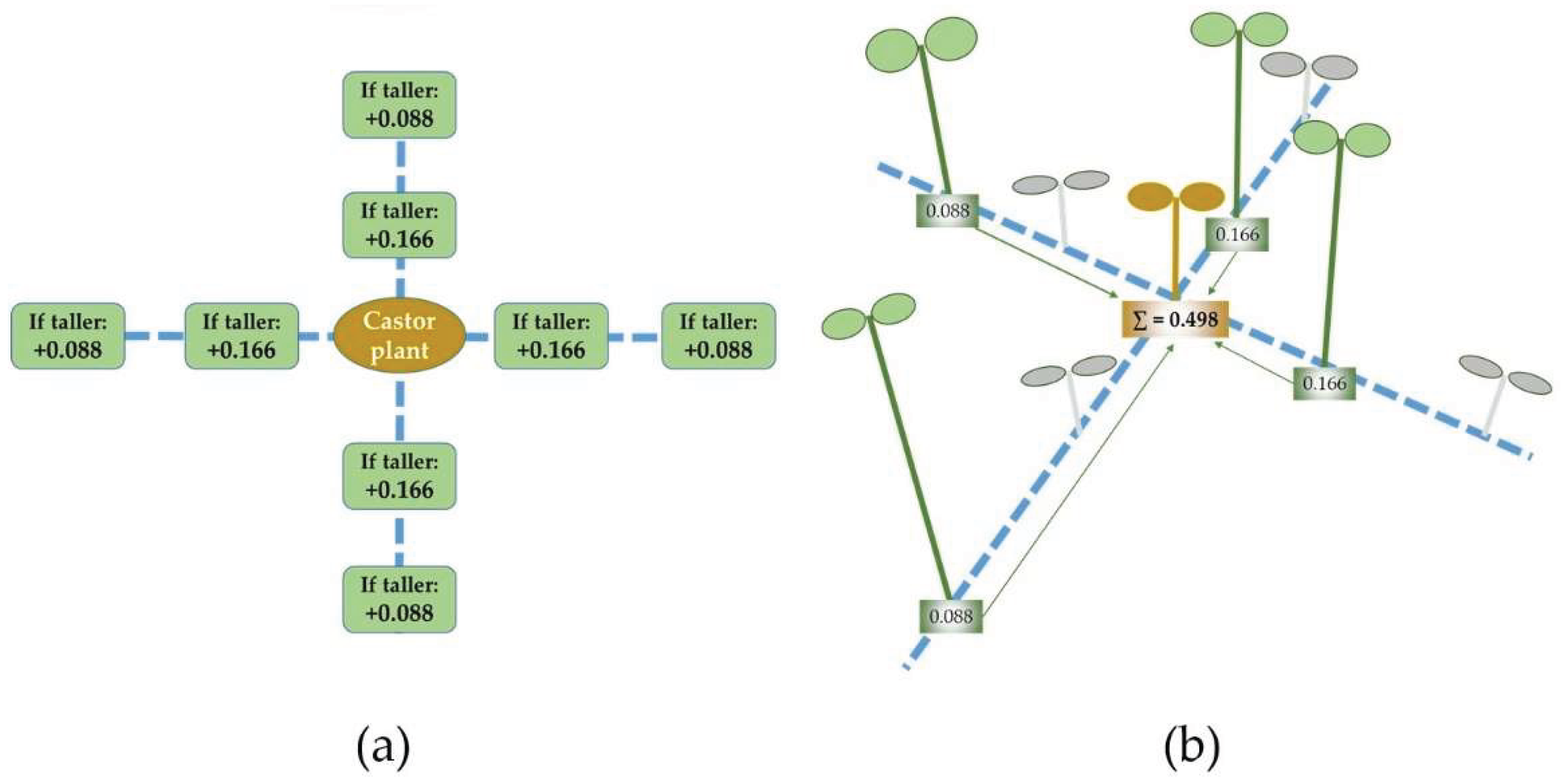

18], a shade index was calculated aiming to account for that effect. The shade index was calculated for each individual plant in each day of the experiment. The distance between plants was approximately 5.5 cm (in the row and between rows). Each plant was compared to eight neighboring plants: four plants in the same row and two plants in each side (

Figure 1a). For each neighboring plant that was taller than it was, a value of 0.166 or 0.088 was added to the shade index if the distance to the other plant was respectively 5.5 or 11 cm (

Figure 1b). The shade index varied from zero (if the plant was taller all the neighboring plants) to one (if the plant was shorter than all the neighboring plants). The trays were placed touching each other in the longest side to allow competition for light among plants growing in adjacent trays. The index considered the absence of competing plants in the short border of the tray.

The castor plants were harvested for measuring the shoot dry weight at 13 days after sowing. Exceptionally, two blocks were harvested only at 14 days after sowing. The shoot was cut, separated in stem and leaves, placed in paper bags, oven dried for 48 h at 105 °C, and individually weighed.

The analysis of the data was made with multiple linear regression. The daily plant height growth was tested for the influence of age, dose of gibberellin, shade, and the interaction of those factors. A value was obtained for each plant in each day after emergence. The dependent variable (

y) was the height growth calculated as in equation (1).

where: Plant height(d) was measured in a given day after emergence and Plant height(d+1) was measured in the following day.

Six values were used as independent variables (

x1 to

x6):

Another analysis was made to quantify the effect on the biomass growth. Four variables related to the biomass accumulated at harvest were evaluated: stem biomass (y1), leaf biomass (y2), total biomass (y3), and stem density (y4). The stem density was calculated as the stem biomass divided by the plant height measured in the last day of the experiment. A multiple linear regression analysis was adopted to test if each of those four variables were influenced by ten independent variables: time after emergence (x1), dose of gibberellin applied on the seed (x2), mean shade index from emergence to harvest (x3), and final plant height (x4). The other six independent variables (x5 to x10) were the product of variable pairs, following the same method as described in the equations 2 to 7.

All the variables were standardized before the regression analysis dividing each individual value by the mean across all the values for that variable. The variables were standardized to make the magnitude of the regression coefficients proportional to the intensity of the effect and comparable to each other. The significance of each regression coefficient was tested (t test, p < 0.10). The results were presented in tables with the regression coefficients and their significance. Some plants died during the experiment. The data collected in those plants were considered for the analysis of daily height growth while they were standing, but they could not be harvested and considered in the analysis of biomass growth. The regression analysis of daily height growth were made with 2,701 data points, and the analysis of accumulated biomass was made on 604 data points.

2.7. Dormancy alleviated by gibberellin and time after harvest

This experiment evaluated if the castor seed post-harvest dormancy is alleviated by the storing time and gibberellin treatment. Emergence tests were repeated periodically for two years. In the first year, the experiment had ten treatments arranged as a factorial distribution of five varieties of castor and the treatment with gibberellin (with or without). In the second year, the same varieties and seed lot from the previous year continued under evaluation excluding the treatment with gibberellin. During the experiment, the seed was stored in paper bags, at room temperature.

The five varieties of castor were harvested at farms and experimental fields in different locations in the State of Mato Grosso, Brazil. The analysis was made assuming that all varieties were harvested when the first test was sown, but the precise harvesting time may be up to 2 weeks before. The varieties were BRS Energia S

3, Kariel, KS 2019, Mia, and RS Otto 01. The last four varieties were hybrid F2 seeds. The variety BRS Energia S

3 was a progeny of plants selected

in vitro for fast germination for two cycles [

4], and later selected for fast emergence at field conditions, as the experiment described in the

Section 2.9.

The emergence tests were performed in 10 plastic trays filled with the same substrate and following the same procedures as described in the

Section 2.1. The test followed a randomized complete block design with 10 treatments and 10 replications, and they were repeated 10 times (from 0 to 624 days after harvest). After 12 months, the emergence tests had only five treatments because the varieties were no longer tested for the gibberellin effect. Each block was a tray, and each experimental unit was a row with five seeds. For the treatment with gibberellin, the seed was incubated at 31 °C, in the dark, for 24 hours, in germination paper soaked with a solution of 200 mg/L of gibberellin. The seed was planted immediately after incubation. The untreated seed was not incubated before sowing. The emergence was daily monitored up to 30 days after sowing, and the plant was discarded just after the emergence was registered.

The complete data set collected in this experiment is available as supplementary material, but just selected results were presented. For the tests made in the first year, the emergence rate was pooled across the five varieties and presented in graphs plotted with the emergence rate observed at 6 and 12 days after sowing, with comparisons (t test, p < 0.05) of the mean emergence rate from the treatments with and without the hormone.

For the tests made along the full period of evaluation, the data was pooled across the five varieties, excluding the seed treated with gibberellin, with the emergence rates observed at 6, 12, and 30 days after sowing. The emergence rate (y) was plotted in function of the time after harvest (x), and subjected to analysis of regression with the exponential model y = y0 +a(1-ebx). Assuming that the maximum emergence rate occurred at the end of the experiment (642 days after harvest), the regression equation was used to estimate how long the seed took to reach 90% of the maximum emergence rate at 12 days after sowing.

In another analysis, the emergence rate was segregated by variety, as observed at 6 and 12 days after sowing, and it was presented in function of the time after harvest (from 0 to 642 days). The emergence rate (y) was subjected to analysis of regression with the exponential model y = y0 +a(1-ebx), and the time after harvest (x) required to reach 90% of the maximum emergence rate was estimated as described in the previous paragraph.

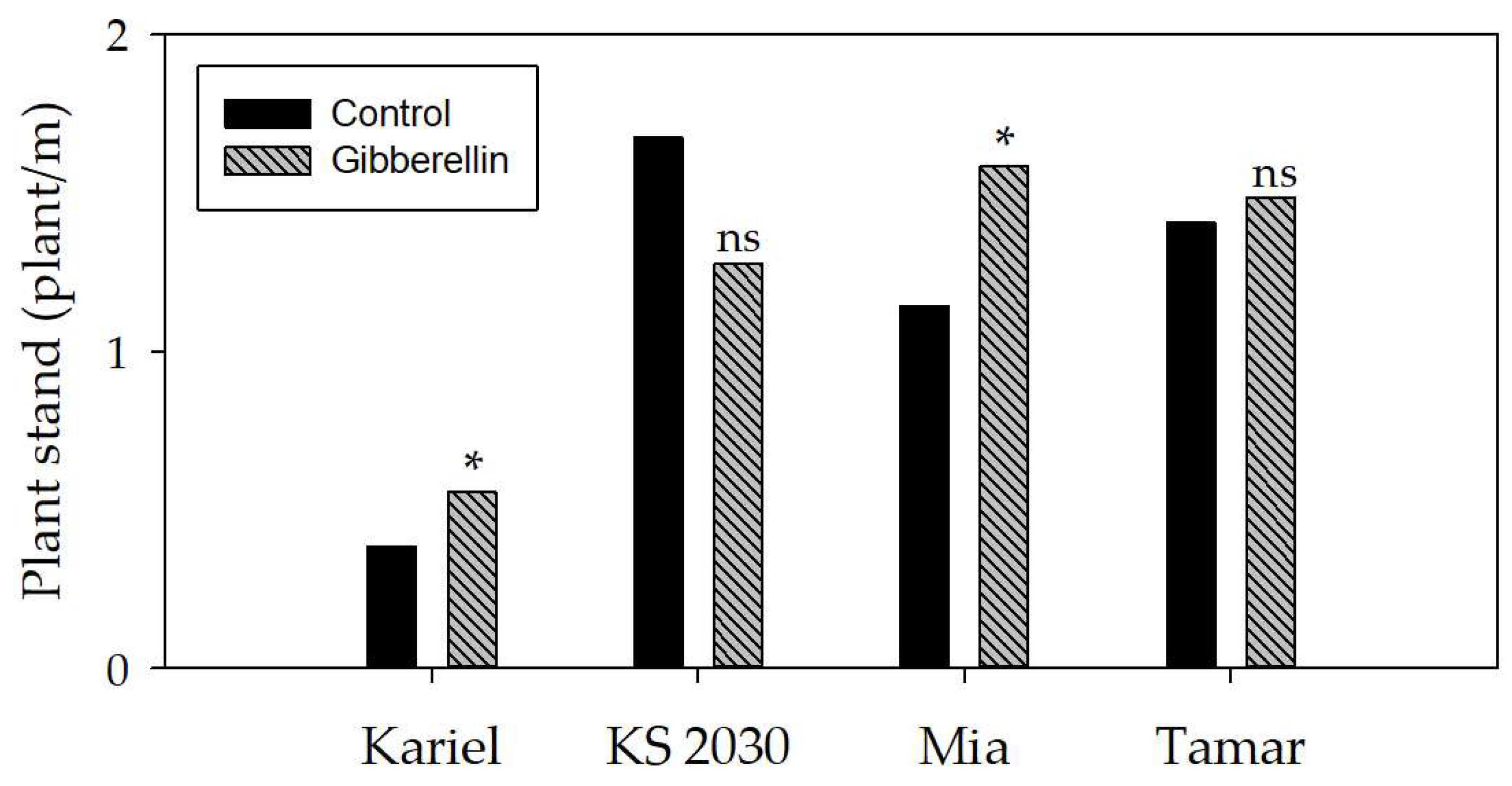

2.8. Gibberellin influencing the initial stand at field conditions

The seed treatment with gibberellin was tested at field conditions for improving the initial stand. The experiment was performed with F1 hybrid seeds of four varieties: Kariel, KS 2030, Mia, and Tamar. The time elapsed since the seed was harvested was not controlled. Part of the seed was assigned to a control treatment, and the other part was treated with 120 mg/kg of gibberellin (ProGibb 400®), diluted in 45 mL of water per kg of seed. After treatment, the seed was allowed to dry for 24 h (at room temperature). The seed was sown in an experimental farm (Sinop, MT, Brazil, 11.8 S, 55.6 W, 370 m.a.s.l), using a five-row planter. Each treatment was planted in two rows, 64-m long each one, with spacing of 0.9 m between rows and 0.33 m between seeds in the row. Between sowing and counting the stand, the mean air temperature was 26.1 °C, and the total precipitation was 108 mm (31 and 60 mm respectively at 2 and 7 days after sowing).

At 12 days after sowing, standing castor plants were counted in 5-m long sections of the rows (24 sections were counted), and the standing was calculated as plants/m. The hypothesis that the plant stand was higher in the treatment with gibberellin in relation to the untreated seed was tested with t test (p < 0.05) for each variety. The comparison was not made among castor varieties.

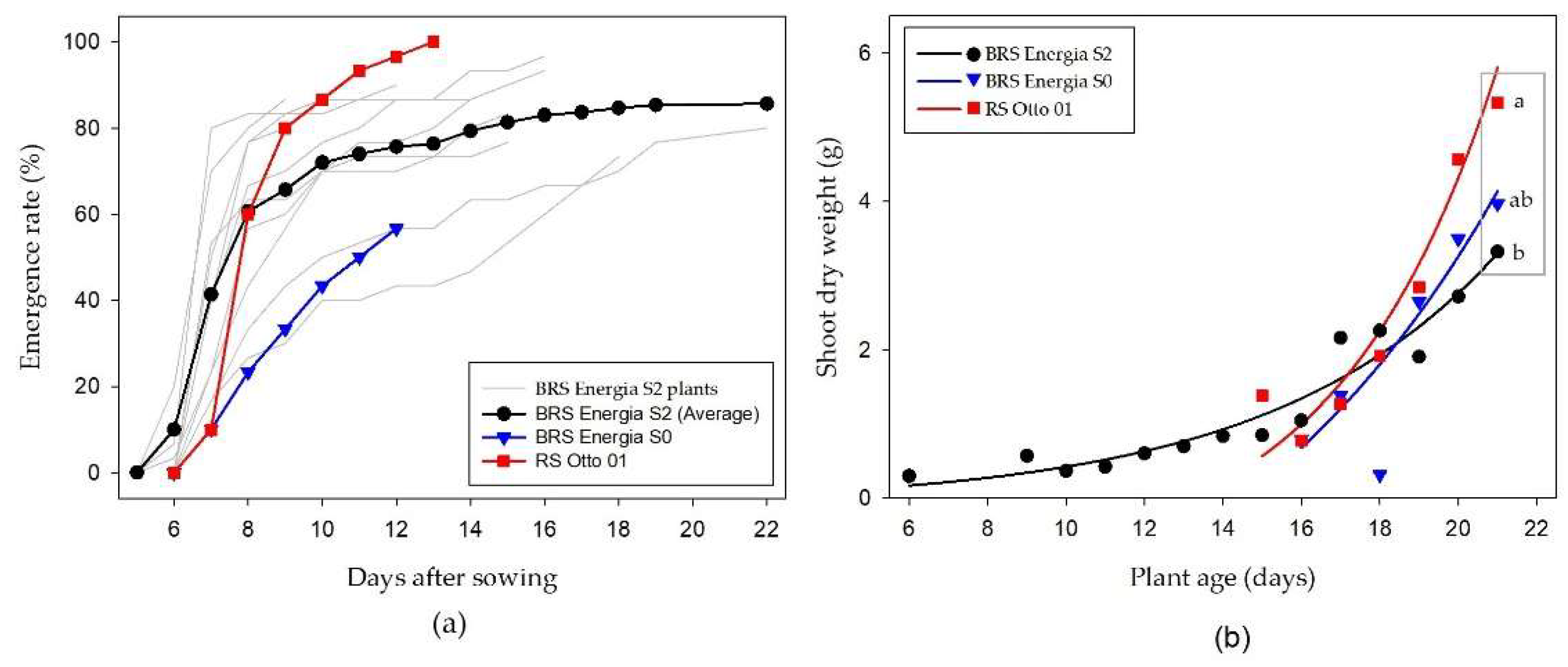

2.9. Emergence and initial growth at field conditions of plants selected for fast germination

Castor plants were selected for fast germination in a previous study [

4]. In short, 200 castor seeds of cv. BRS Energia were incubated for germination, and the 10 seeds that germinated faster were selected and planted for growing and producing seeds. This procedure was repeated for two cycles of selection.

The current experiment evaluated if the prior selection for fast germination improved the time for emergence at field conditions, and it the same time it performed the third cycle of selection (for fast emergence). The seed harvested from 10 castor plants (BRS Energia S

2) subjected to two cycles of selection [

4] were sown at field conditions (Sinop, MT, Brazil, 11.9 S, 55.6 W, 370 m.a.s.l). Thirty seeds were obtained from each of 10 S

2 plants, and, as control treatment, 30 seeds were used from the original seed lot that was used to begin the selection for fast germination (BRS Energia S

0) and 30 seeds from the variety RS Otto 01 (F1 hybrid seed), totaling 360 castor seeds. The seeds were not treated with gibberellin or any pre-germination procedure. The experimental plot consisted of 10 furrows, 12 m long and 5 cm deep, and the distance between seeds was 0.33 m. The seeds from all treatments were randomly assigned along the five furrows, registering the exact position of each seed to be associated with the genotype. Chemical fertilizers were buried in a parallel furrow, 5-cm beside the sowing furrow, in a dose equivalent to 45-150-100 kg/ha of N, P, and K, respectively. In the 29 days from sowing to the shoot harvest, the average air temperature was 25.1 °C, and the total precipitation was 315 mm (7 mm a few hours after sowing and 27 mm on the third day).

The experiment was monitored daily to register the time of emergence of each seedling, and the 10 earliest-emerging plants from the BRS Energia S

3 line were selected to keep growing and produce seeds. At 29 days after sowing, the shoot of all the plants (except the 10 early-emerged) were clipped, placed in paper bags, oven-dried, and individually weighed. Seven plants died during the experiment attacked by pest and diseases. The ten fast-emerged plants were allowed to grow and produce seeds, which were harvested and used in the experiment described in the

Section 2.7 (BRS Energia S

3). Castor seed yield was not measured.

The daily progress of accumulated emergence rate was calculated for each genotype and presented graphically. The data on shoot dry weight (y) was plotted in function of the plant age at harvest (x) and subjected to regression analysis with the model y = y0 +aebx. The data from the ten plants BRS Energia S2 were pooled in just one regression line. The regression line for each treatment was calculated with the replicated data, but only the means were displayed in the graphs. The means of shoot dry weight from the 21-days old plants (BRS Energia S3, BRS Energia S0, and RS Otto 01) were compared with t test (p < 0.05).

2.10. Volunteer castor plants emerging after a soil disturbance

This experiment attempted to simulate the phenomenon of castor seed that remains dormant in the soil and emerge as volunteer plants just after a soil disturbance. The study was made with five varieties of F2 hybrid seeds (AKB 10, Kariel, KS 2030, Mia, and RS Otto 01) obtained from commercial production and field experiments in the State of Mato Grosso, Brazil. The experiment was sown about 60 days after the seed was harvested.

The seed was sown in 10-L pots filled with soil. For each variety, ten pots were sown with 40 seeds each one, the seed was buried at the depth of 3 cm. The pots were kept in a greenhouse, and they were continually irrigated for 170 days. The plant emergence was registered daily, and the plant was removed after emergence.

At 170 days after sowing, the substrate was sieved and washed to simulate a soil disturbance and to recover the ungerminated seeds that still had the seed coat preserved. The recovered seeds were sown again, placed on top of the same substrate, covered with 4 cm of carbonized rice husks, and returned to the daily irrigation for an additional period of 60 days. It was expected that some of the recovered seeds were alive and dormant, and they would germinate after the disturbance; however, all the ungerminated seeds were dead, and there was no emergence.

3. Results

All the raw data from the experiments are available as supplementary material, while the most relevant results were selected and presented as follow.

3.1. Seed position influencing the emergence rate

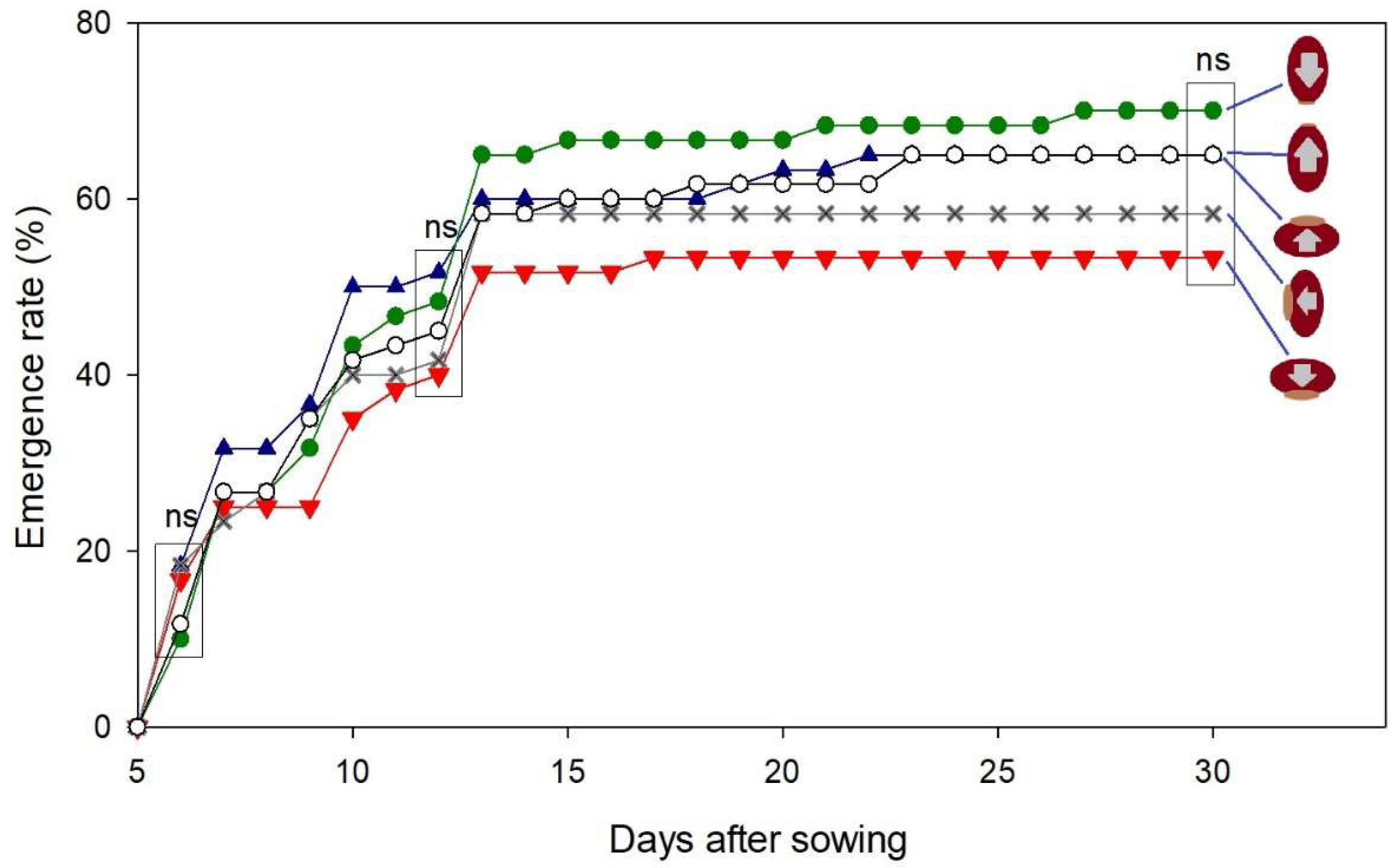

The rate of castor seedling emergence at 6 days after sowing was not influenced by the direction of the seed in the soil (

Figure 1). The observations made at 12 and 30 days after sowing confirmed that the seed direction did not influence the progress of germination and emergence. The seed direction would be an important factor if it influenced the emergence at 6 days after sowing, but such influence was not observed.

The influence of seed direction on germination was tested in a similar experiment, but rather than the direction, it tested the region of the seed that was in contact with the soil through where the seed coat could be more permeable to the water [

19]. On that experiment, higher germination was obtained when the region of the caruncle was touching the soil, while the lowest germination occurred when the caruncle was upward (without touching the soil) [

19].

Figure 2.

Progress of the emergence rate of castor seedling according to the direction of the seed in the soil. The letters “ns” means not significant in the test of Tukey (p < 0.05) for comparison of the treatments at 6, 12, and 30 days after sowing.

Figure 2.

Progress of the emergence rate of castor seedling according to the direction of the seed in the soil. The letters “ns” means not significant in the test of Tukey (p < 0.05) for comparison of the treatments at 6, 12, and 30 days after sowing.

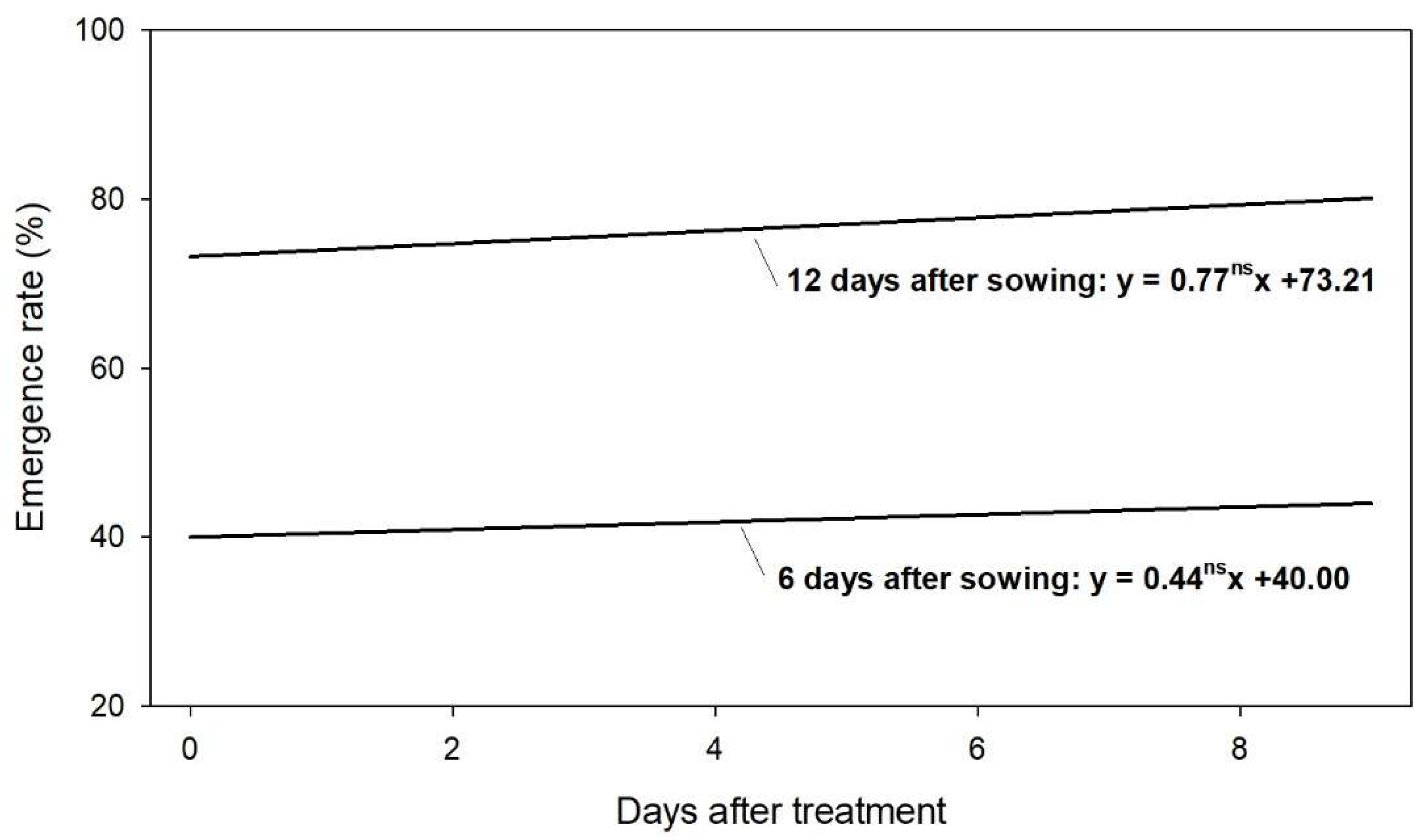

3.2. Period between gibberellin treatment and sowing

Castor seeds that were treated with gibberellin could be stored up to 9 days without losing the hormone effect on the emergence (

Figure 3). The castor seed treatment in a farm may be occasionally performed many days before sowing, and this experiment tested if that interval could potentially reduce the effect of the hormone. On the evaluated period, no reduction on the emergence rate was observed; however, it should be highlighted that the dose of gibberellin evaluated (400 g/kg) was very high and in excess of the minimal dose that would be effective for improving emergence performance of castor seedlings. Therefore, it should be considered the hypothesis that the hormone can lose efficiency if applied at lower doses.

The period of 9 days simulates a seed treatment made in the farm in a short period prior to sowing. Further studies should consider if the gibberellin treatment would remain effective for some months for allowing the hormone to be applied by the seed industry.

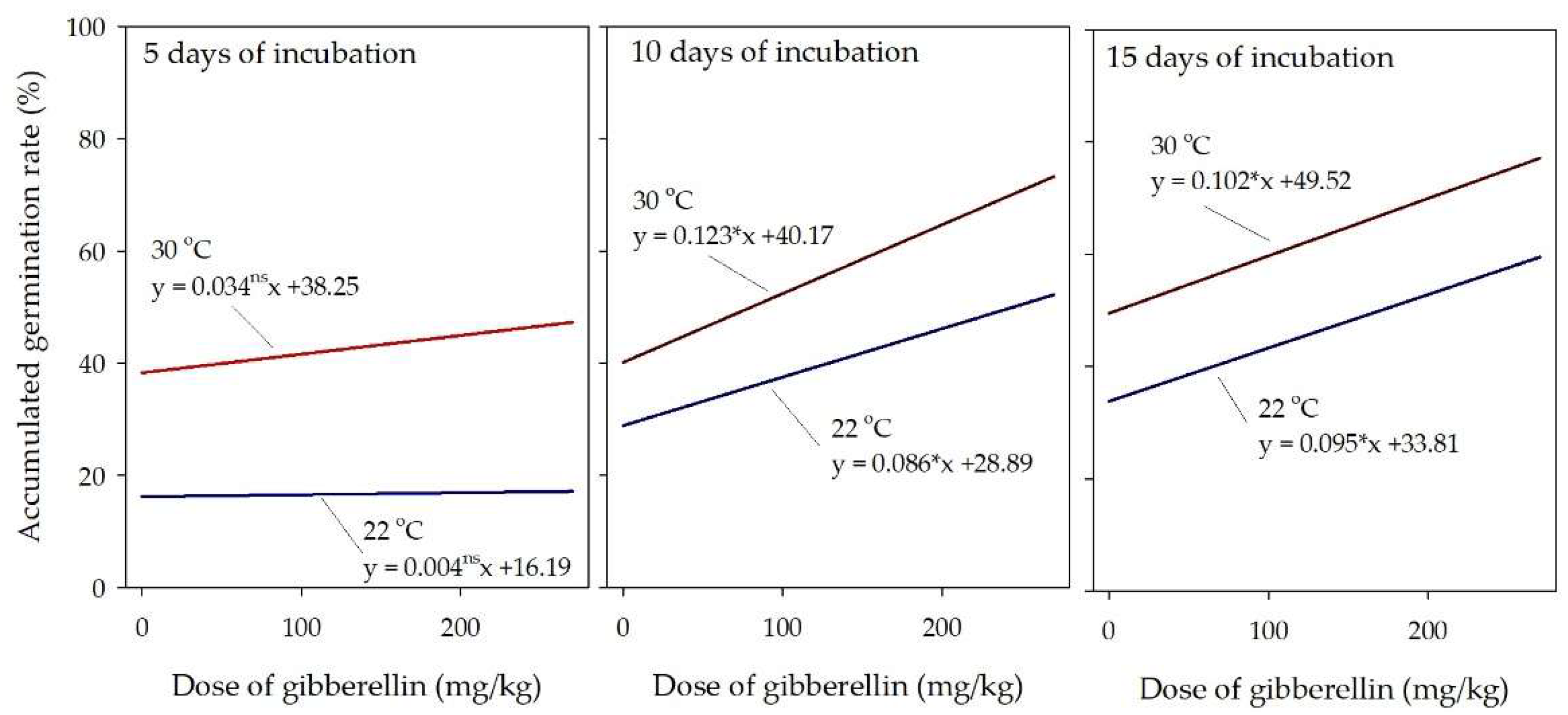

3.3. Gibberellin alleviating the effect of suboptimal temperature

The treatment with gibberellin increased the germination rate of castor seed at suboptimal temperature (22 °C) in the observations made at 10 or 15 days of incubation, and the improvement was proportional to the hormone dose (

Figure 4). After 5 days of incubation, the hormone effect was not significant. The highest germination rate was observed in the seeds treated with gibberellin and incubated at optimal temperature (30 °C).

The most relevant observation from this experiment was that gibberellin was effective to influence the time for germination of castor seed under suboptimal temperature. Considering the germination observed at 10 days of incubation, an estimated dose of 131 mg/kg of gibberellin made the seed germinating at suboptimal temperature equals the rate of the untreated seed at optimal temperature. At 15 days of incubation, the estimated dose of gibberellin to counterbalance the effect of the suboptimal temperature was 165 mg/kg.

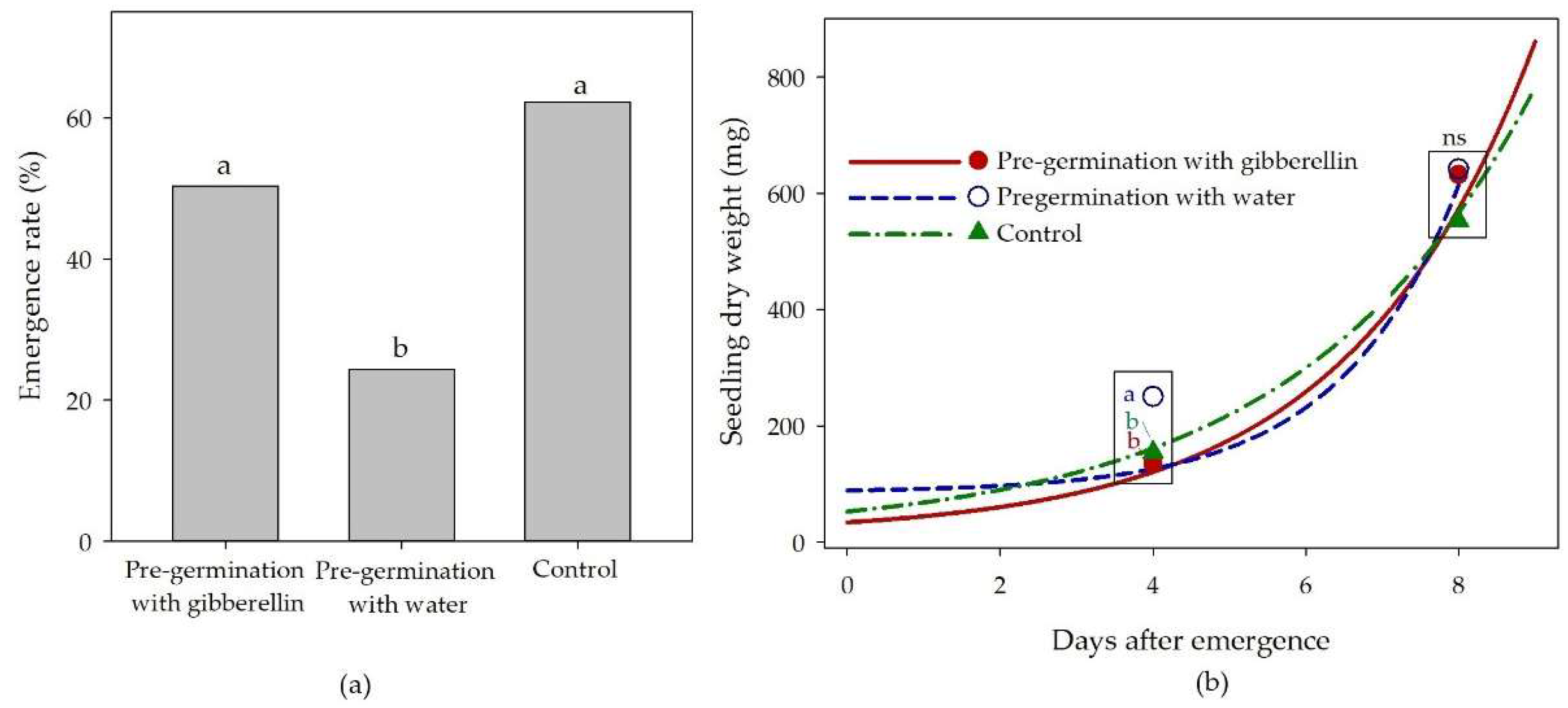

3.4. Pre-germination of castor seed

The pre-germination of castor seed using water followed by oven drying reduced the final emergence rate to 24.6%, while the same procedure using a solution of gibberellin sustained the final emergence rate at 50.4%, which was statistically equal to 62.2% of emergence rate observed in the control treatment (

Figure 5a). The proposed reason for this effect was that the high temperature that the moist seeds were exposed for drying (45 °C, 24 hours) was stressful and promoted the production of abscisic acid, which inhibited germination. As the germination is driven by the balance between gibberellin and abscisic acid [

20], it is likely that the promoting-hormone that was applied for pre-germination counterbalanced the inhibiting-hormone produced in the high temperature applied for drying the seed. The seed was sown immediately after oven drying. Further studies should test this hypothesis on abscisic acid and evaluate if the proposed inhibiting effect would remain relevant after the seed was stored for some months.

Although the pre-germination influenced the emergence rate, the growth potential of the seedlings was not influenced. The seedlings pre-germinated with water and harvested at 4 days after emergence, occasionally, had the biomass significantly higher than the other two treatments (

Figure 5b); however, the biomass of plants harvested at 8 days after emergence were statistically equal, demonstrating that the pre-germination treatments did not influence the growth potential of the plants. The trend lines (

Figure 5b) corroborate that the growth was similar among the treatments.

It is noteworthy that the biomass growth of castor seedlings for a few days following emergence follows an exponential pattern rather than a linear growth (

Figure 5b). On average of the three treatments, the estimated shoot dry weight of the 4-days old seedlings was 136.3 mg/plant, and it increased to 586.6 mg/plant in the 8-days old seedling. The plants that emerged just 4 days earlier had a shoot biomass 4 times greater. This pattern of growth explains why, at field conditions, the slow and uneven germination and emergence has such a significant influence on the yield potential of castor plants.

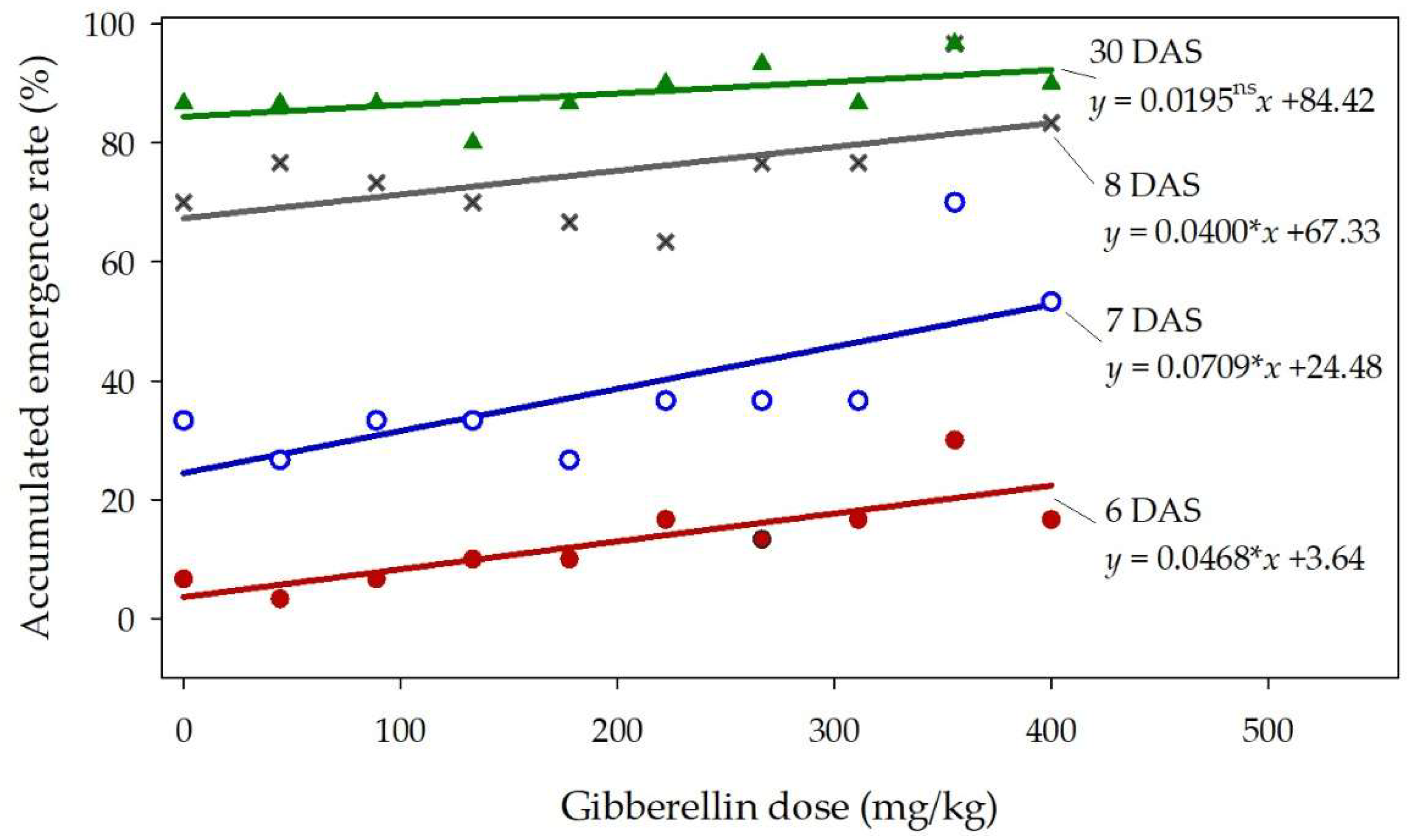

3.5. Seed treated with high doses of gibberellin

The emergence of castor seedlings was significantly promoted by high doses of gibberellin especially between 6 and 8 days after sowing (

Figure 6). At 6 days after sowing, the emergence rate from untreated seeds was estimated as 3.6%, while in the dose of 400 mg/kg, the emergence rate was 22.4%. One day later, the emergence rate was increased from 24.5% (in the dose 0 mg/kg) to 52.8% (in the dose 400 mg/kg). The gibberellin effect was still significant at 8 days after sowing, but it gradually lost intensity each day, and at the end of the experiment (30 days after sowing) the hormone was no longer effective. The seedlings were not allowed to grow longer than the first day, but at that early phase, there was no sign of deformation or atypical development that could be associated with problems caused by high doses of gibberellin.

3.6. Residual effect of gibberellin influencing stem elongation and biomass accumulation

When the effect of several variables were analyzed together, the most relevant influence on castor plants height growth (−0.297*) was the plant age (

Table 2). The rate of stem elongation is higher in the first day after emergence, and it reduces each day. On the average across all treatments, the stem elongation was 1.9 cm/day in the first day after emergence, and it reduced linearly to 0.8 cm/day at 8 days after emergence. The second most relevant driver for stem elongation was the shade intensity (0.238*), confirming that the plant elongates the stem in response to the shade condition as an attempt to outgrow the neighboring plants [

18].

The most important objective of this experiment was to test if the gibberellin applied on the seed would cause a residual effect influencing the stem elongation. The direct effect of gibberellin on stem elongation was not significant (0.040 ns), but it was relevant when combined with the shade index (−0.043*). It seems that some of the gibberellin applied on the seed treatment is carried to the seedling, but its concentration is too low to influence the stem elongation; however, it adds to the gibberellin produced by the plant in response to the shade condition, and the hormone reaches the threshold to induce a significant change in the stem growth.

The interaction between plant’s age and shade index was also significant for the daily stem elongation. The plant tends to grow less each day, but the shade condition interacts to maintain longer the stimuli for stem elongation.

Regarding the dry weight growth, the most relevant observation was that gibberellin did not influence the biomass accumulation in any compartment, either directly or in combination with the other variables considered in the analysis (

Table 3). Specifically for the stem biomass, the only significant influence was observed on the combined effect of plant age and final plant height (0.622*), demonstrating that more biomass accumulated in the stem along the time and as the plant grew taller. At that early phase of plant growth, the stem biomass was not proportional to the age (−0.011

ns) nor was it influenced by the shade intensity (0.024

ns).

As for the leaf biomass, the main driver was the plant age (0.721*). The interpretation was that the biomass was preferentially allocated to grow leaves when the plant was taller (0.435*) and consequently had adequate light incidence, but the opposite was observed when the plant was shaded (−0.204*).

The total biomass (stem + leaves) accumulated proportionally to the plant age (0.497*), with a positive interaction when the plant was taller (0.493*), and a negative interaction when the plant was shaded (-0.160*).

The stem density was significantly influenced by two factors (

Table 3). Taller plants were associated with reduced stem density (−0.684*); however, when the plant height was combined with the plant age, it was observed that the stem density increased when the height growth was observed in older plants (0.595*).

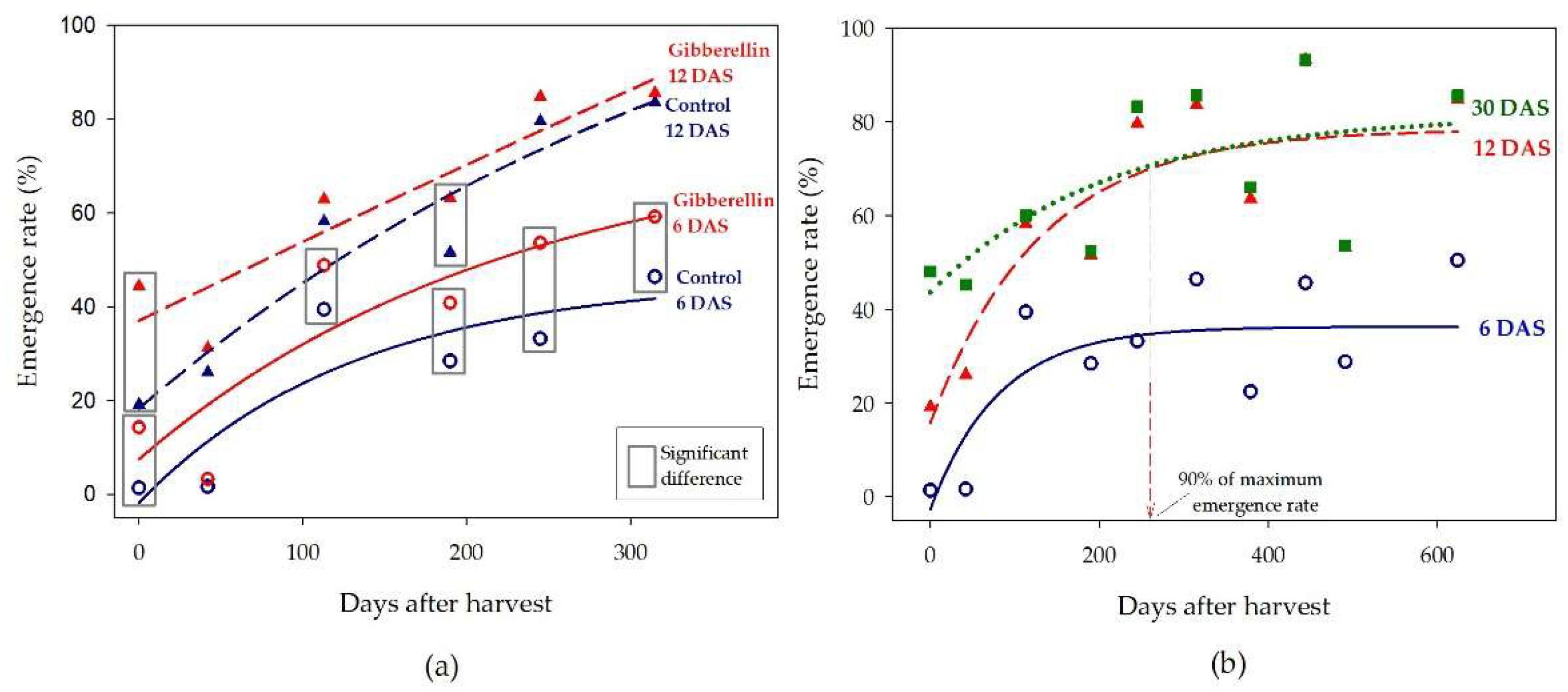

3.7. The dormancy is released according to the time after harvest

The emergence rate was very low on castor seeds sown a few days after harvest. The early emergence, observed at 6 days after sowing, was initially near zero, and it was gradually increased to reach 44% after 315 days of storage (

Figure 7a). The same pattern occurred in the emergence rate observed at 12 days after sowing, as it increased from 19% just after harvest to 84% of emergence after the seed was stored for one year. The effect of gibberellin was the most relevant in the early emergence (at 6 days after sowing) and in the seed that was stored for short time after harvest. The effect remained significant in the emergence rate observed at 6 days after sowing despite the time elapsed after harvest, while the beneficial effect of gibberellin in the emergence rate observed at 12 days after sowing was gradually reduced along the storing time. On the average of five varieties, the emergence rate observed at 12 days after sowing reached 90% of the maximum at approximately 260 days after harvest (

Figure 7b). Just after harvest, the emergence was uneven, and there was large difference between the emergence rate at 12 and 30 days after sowing. After the first year, most of the plants had emerged at 12 days after sowing, and plants emerging between 12 and 30 days were scarce.

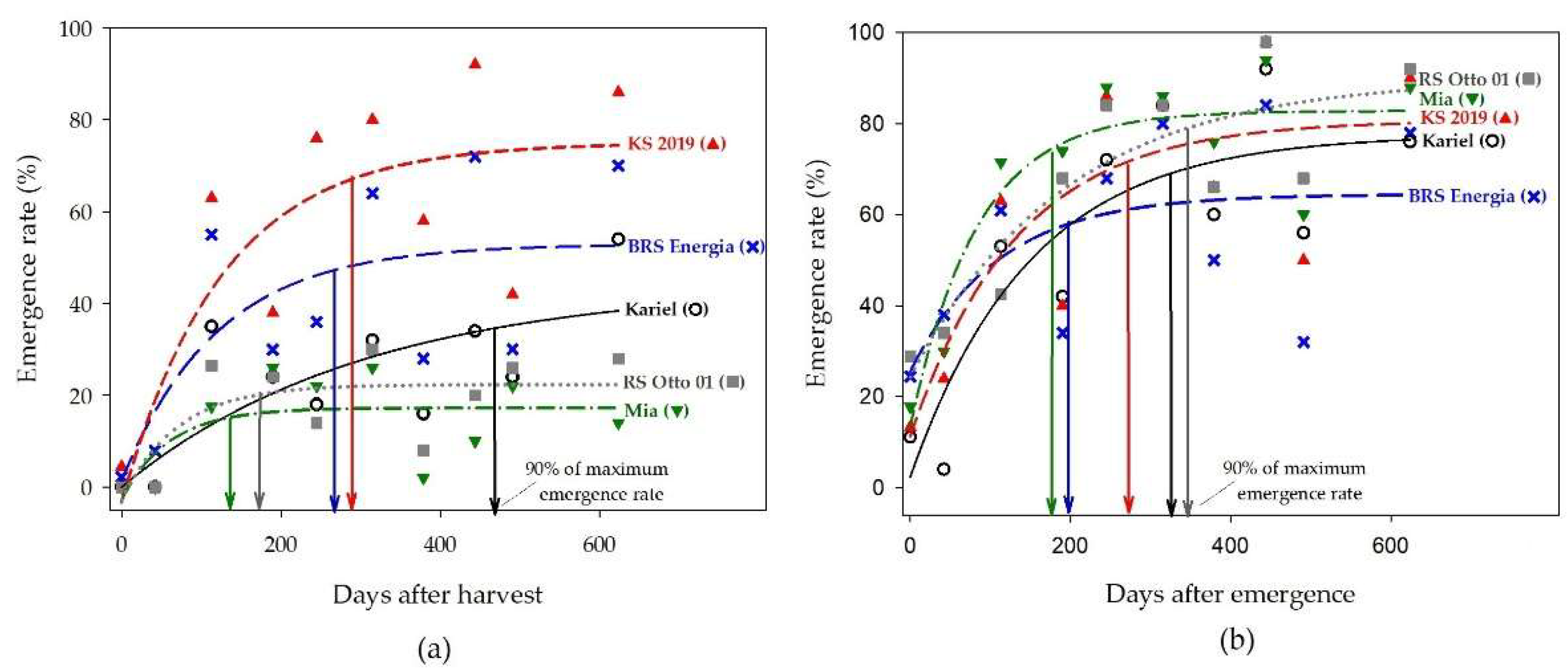

Just after harvest, all the five castor varieties had low emergence rate at 6 days after sowing (

Figure 8a). As the seed was stored, the dormancy was gradually released in different intensities among the varieties. The emergence rate at 6 days after sowing was the highest in the varieties KS 2019 and BRS Energia S

3 and the lowest in the varieties Mia and RS Otto 01. At 12 days after sowing (DAS), the ranking was inverted, and the highest emergence rate was observed in the varieties RS Otto 01 and Mia, and the lowest emerge rate was observed in the BRS Energia S

3 and Kariel (

Figure 8b).

The time to reach 90% of the maximum emergence rate varied in a wide range from 175 to 340 days after harvest. The variability observed cannot be completely explained by the genotypic difference among varieties because it should be considered that the seeds were produced in different environments, and this characteristic can be influence by factors such as temperature, drought stress intensity, and plant nutrition.

3.8. Seed treatment with gibberellin influencing initial stand at field conditions

Two out of four castor varieties had the initial stand significantly improved as the effect of seed treatment with gibberellin (

Figure 9). The treatment was effective for improving the emergence of varieties Kariel and Mia, but it was ineffective for KS 2030 and Tamar. The gibberellin effect was more relevant in the two varieties with the lowest emergence rate.

3.9. Emergence and initial growth at field conditions of castor plants selected for fast germination

The seeds from plants previously selected for fast germination [

4] were confirmed to emerge faster at field conditions, but high variability and a trade-off were observed. On average, the genotype BRS Energia S

2 emerged ahead of the two control treatments (

Figure 10a). For instance, at 7 days after sowing, the mean emergence rate of BRS Energia S

2 was 41% (the seeds from two plants had emergence rate of 70 and 80%), ahead of the two varieties sown as control treatments, in which only 10% had emerged. Nevertheless, not all the S

2 seeds had fast emergence, as two of them were considerably delayed. The seed lot of BRS Energia S

0 (original seed used for selection) had low emergence rate probably because it deteriorated after being stored for at least three years.

A potential trade-off was observed between the selection for fast emergence and biomass accumulation. Seeds produced by BRS Energia S

2 plants emerged earlier, but they were not able to accumulate shoot biomass as the control varieties (

Figure 10b). The growth rate of RS Otto 01 plants was considerably higher than the fast emerging BRS Energia S

2, and that is true in relation to the two genotypes that were outstanding in fast emergence (this specific data was not detailed in

Figure 10b). There is some chance that the selection for fast emergence caused a reduction on plant vigor and early growth potential; however, this trade-off requires further studies.

Another relevant observation was that, at 21 days after emergence, castor plants were still under exponential biomass growth. Previous studies had demonstrated this growth pattern for shorter periods and in pot studies (

Figure 5b and [

5]). For illustration, the mean shoot biomass in the variety RS Otto 01 increased from 1.3 g (17 days old) to 2.9 g (19 days old) and 5.3 g (21 days old), demonstrating that the shoot dry biomass doubled every two days.

3.10. Dormant castor seeds germinating after a soil disturbance

This experiment attempted to simulate breaking seed dormancy by a soil disturbance. On average of the five varieties, the emergence rate evolved as demonstrated in the other experiments, beginning as 7% at 6 days after sowing, reaching 69% at 12 days after sowing, and stabilizing at 72% at 20 days after sowing. There was negligible emergence after that point (only 0.3%) for 6 months. Among varieties, the final emergence rate varied from 57 to 86%. The soil disturbance was applied at 170 days after sowing, expecting that some seeds would be just dormant, and they would then germinate. Nevertheless, at that point, all the seeds that failed to emerge were in fact dead instead of dormant.

The useful observation from this failed attempt was that all the viable castor seed germinated when exposed to adequate conditions of moisture and temperature. In cultivated castor fields, volunteer plants occur in areas previously cultivated with castor, as seeds are dropped on the soil surface, and they are exposed to high temperatures and drought for some months. Further studies on the factors related to volunteer castor plants should simulate those specific conditions in order to induce dormancy before exposing the seed to suitable conditions for germination.

Figure 1.

(a) Comparison of the castor plant with eight neighboring plants for calculation of the shade index according to the plant height. (b) Example of the shade index calculated for a castor plant surrounded by eight plants with different heights. Green plants are taller and gray plants are shorter.

Figure 1.

(a) Comparison of the castor plant with eight neighboring plants for calculation of the shade index according to the plant height. (b) Example of the shade index calculated for a castor plant surrounded by eight plants with different heights. Green plants are taller and gray plants are shorter.

Figure 3.

Analysis of regression of the time after the treatment with gibberellin (x) influencing the emergence rate (y) of castor seedling at 6 and 12 days after sowing. The letters “ns” after the regression coefficient denote that the regression was not significant (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Analysis of regression of the time after the treatment with gibberellin (x) influencing the emergence rate (y) of castor seedling at 6 and 12 days after sowing. The letters “ns” after the regression coefficient denote that the regression was not significant (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Accumulated germination rate of castor seed treated with gibberellin at doses varying from 0 to 270 mg/kg, observed at 5, 10, and 15 days of incubation. The letters ns and * after the regression slope denote respectively that the linear regression model was not-significant and significant (p < 0.10).

Figure 4.

Accumulated germination rate of castor seed treated with gibberellin at doses varying from 0 to 270 mg/kg, observed at 5, 10, and 15 days of incubation. The letters ns and * after the regression slope denote respectively that the linear regression model was not-significant and significant (p < 0.10).

Figure 5.

(a) Emergence rate after 16 days of incubation of castor seedlings originated from seeds pre-germinated with gibberellin or water – different letters displayed on the top of columns denote significant difference among means (test of Tukey, p < 0.05); (b) shoot dry weight of castor seedlings (y) according to the pre-germination treatment and the time after emergence (x) – different letters inside the frame at 4 days after emergence denote significant difference among the means (test of Tukey, p < 0.05), “ns” in the frame at 8 days after emergence denotes that the means were not different (test of Tukey, p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

(a) Emergence rate after 16 days of incubation of castor seedlings originated from seeds pre-germinated with gibberellin or water – different letters displayed on the top of columns denote significant difference among means (test of Tukey, p < 0.05); (b) shoot dry weight of castor seedlings (y) according to the pre-germination treatment and the time after emergence (x) – different letters inside the frame at 4 days after emergence denote significant difference among the means (test of Tukey, p < 0.05), “ns” in the frame at 8 days after emergence denotes that the means were not different (test of Tukey, p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Accumulated emergence rate (y) of castor seedlings at 6, 7, 8, and 30 days after sowing (DAS) as influenced by seed treatment with doses of gibberellin (x) varying from zero to 400 mg/kg. The letters * and ns after the regression slope denote respectively that the linear model was significant (p < 0.10) and non-significant.

Figure 6.

Accumulated emergence rate (y) of castor seedlings at 6, 7, 8, and 30 days after sowing (DAS) as influenced by seed treatment with doses of gibberellin (x) varying from zero to 400 mg/kg. The letters * and ns after the regression slope denote respectively that the linear model was significant (p < 0.10) and non-significant.

Figure 7.

(a) Mean emergence rate of castor seedlings at 6 and 12 days after sowing, with or without gibberellin seed treatment. The squares encompassing the data points denote that the effect of gibberellin was significant (t test, p < 0.05). (b) Progress of the mean emergence rate of castor seedlings according to the time after harvest, observed at 6, 12, and 30 days after sowing. The vertical red arrow marks the time after harvest that the seed reached 90% of the maximum emergence rate at 12 days after sowing.

Figure 7.

(a) Mean emergence rate of castor seedlings at 6 and 12 days after sowing, with or without gibberellin seed treatment. The squares encompassing the data points denote that the effect of gibberellin was significant (t test, p < 0.05). (b) Progress of the mean emergence rate of castor seedlings according to the time after harvest, observed at 6, 12, and 30 days after sowing. The vertical red arrow marks the time after harvest that the seed reached 90% of the maximum emergence rate at 12 days after sowing.

Figure 8.

Emergence rate of five castor varieties, according to the time after harvest. The vertical arrows mark the time after harvest that the variety reached 90% of the maximum emergence rate after stored for two years after harvest. (a) observed at 6 days after sowing; (b) observed at 12 days after sowing.

Figure 8.

Emergence rate of five castor varieties, according to the time after harvest. The vertical arrows mark the time after harvest that the variety reached 90% of the maximum emergence rate after stored for two years after harvest. (a) observed at 6 days after sowing; (b) observed at 12 days after sowing.

Figure 9.

Initial stand of castor plants at field conditions, 12 days after sowing, with or without seed treatment with gibberellin. The letters * and “ns” on the top of the columns denote respectively that the effect of gibberellin treatment was positively significant and not-significant (t test, p < 0.05).

Figure 9.

Initial stand of castor plants at field conditions, 12 days after sowing, with or without seed treatment with gibberellin. The letters * and “ns” on the top of the columns denote respectively that the effect of gibberellin treatment was positively significant and not-significant (t test, p < 0.05).

Figure 10.

(a) Progress of emergence rate of castor plants at field conditions, originated from seeds produced by genotypes previously selected for fast germination (BRS Energia S2) and compared with the original seed (BRS Energia S0) and to the cultivar RS Otto 01. (b) Shoot dry weight of three castor varieties according to the plant age at harvest. The means followed by different letters inside the gray frame are significantly different by t test (p < 0.05).

Figure 10.

(a) Progress of emergence rate of castor plants at field conditions, originated from seeds produced by genotypes previously selected for fast germination (BRS Energia S2) and compared with the original seed (BRS Energia S0) and to the cultivar RS Otto 01. (b) Shoot dry weight of three castor varieties according to the plant age at harvest. The means followed by different letters inside the gray frame are significantly different by t test (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Directions of castor seed evaluated for their influence on germination and time for seedling emergence.

Table 2.

Coefficients of multiple linear regression1 testing the effect of the plant age, dose of gibberellin, shade index, and their double interactions on the daily height growth of castor plants.

Table 2.

Coefficients of multiple linear regression1 testing the effect of the plant age, dose of gibberellin, shade index, and their double interactions on the daily height growth of castor plants.

| Influencing variable tested |

Regression coefficient |

| Plant age |

−0.297* |

| Dose of gibberellin |

0.040 ns

|

| Shade index |

0.238* |

| Plant age × dose of gibberellin |

−0.049ns

|

| Plant age × shade index |

−0.171* |

| Dose of gibberellin × shade index |

−0.043* |

Table 3.

Coefficients of multiple linear regression testing the effect of the plant age, dose of gibberellin, mean shade index, final plant height, and their double interactions on four characteristics related to biomass accumulation on castor plants.

Table 3.

Coefficients of multiple linear regression testing the effect of the plant age, dose of gibberellin, mean shade index, final plant height, and their double interactions on four characteristics related to biomass accumulation on castor plants.

| Plant compartment |

Influencingvariable |

Regression coefficient |

| Stem biomass1 |

Plant age |

−0.011ns

|

| Dose of gibberellin |

−0.067ns

|

| Shade index |

0.024ns

|

| Final plant height |

0.283ns

|

| Plant age × dose of gibberellin |

−0.070ns

|

| Plant age × shade index |

−0.060ns

|

| Plant age × final plant height |

0.622* |

| Dose of gibberellin × shade index |

0.028ns

|

| Dose of gibberellin × final plant height |

0.094ns

|

| Shade index × final plant height |

−0.086ns

|

| Leaf biomass2 |

Plant age |

0.721* |

| Dose of gibberellin |

0.034ns

|

| Shade index |

−0.107ns

|

| Final plant height |

−0.450ns

|

| Plant age × dose of gibberellin |

−0.095ns

|

| Plant age × shade index |

−0.204* |

| Plant age × final plant height |

0.435* |

| Dose of gibberellin × shade index |

0.025ns

|

| Dose of gibberellin × final plant height |

0.031ns

|

| Shade index × final plant height |

0.109ns

|

| Total biomass3 |

Plant age |

0.497* |

| Dose of gibberellin |

0.003ns

|

| Shade index |

-0.067ns

|

| Final plant height |

-0.225ns

|

| Plant age × dose of gibberellin |

-0.087ns

|

| Plant age × shade index |

-0.160* |

| Plant age × final plant height |

0.493* |

| Dose of gibberellin × shade index |

0.026ns

|

| Dose of gibberellin × final plant height |

0.050ns

|

| Shade index × final plant height |

0.049ns

|

| Stem density4 |

Plant age |

−0.052ns

|

| Dose of gibberellin |

0.008ns

|

| Shade index |

−0.077ns

|

| Final plant height |

−0.684* |

| Plant age × dose of gibberellin |

−0.077ns

|

| Plant age × shade index |

−0.007ns

|

| Plant age × final plant height |

0.595* |

| Dose of gibberellin × shade index |

0.013ns

|

| Dose of gibberellin × final plant height |

0.039ns

|

| Shade index × final plant height |

−0.027ns

|