Submitted:

26 June 2023

Posted:

27 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Preparing Solutions and Performing Seed Priming

2.3. Experimental Layout

2.4. Germination-Related Traits

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crane, JH.; Balerdi, CF. Pitaya growing in the Florida home landscape. 2005, IFAS Extension. Florida, United States.

- Wu, LC. ; Hsu, HW. ; Chen, YC. ; Chiu, CC. ; Lin, YI.; Ho, JAA. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of red pitaya. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 319–327. [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, P.; Stintzing, FC.; Carle, R. Comparison of morphological and chemical fruit traits from different pitaya genotypes (Hylocereus sp.) grown in Costa Rica. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2007, 81, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cheok, A.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Caton, PW.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A. Betalain-rich dragon fruit (pitaya) consumption improves vascular function in men and women: A double-blind, randomized controlled crossover trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2022, 115, 1418–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikito, DF.; Borges, ACA. ; Laurindo, LF.; Otoboni, AMB.; Direito, R.; Goulart, RDA.; Nicolau, CCT.; Fiorini, AMR.; Sinatora, SM.; Barbalho, SM. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and other health effects of dragon fruit and potential delivery systems for ıts bioactive compounds. Pharmaceutics. 2023, 15, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariffin, AA.; Bakar, J.; Tan, CP.; Rahman, RA.; Karim, R.; Loi, CC. Essential fatty acids of pitaya (dragon fruit) seed oil. Food chem. 2009, 114, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, MH.; Raihan, MT.; Shakhik, MTZ.; Khan, FT.; Islam, MT. Dragon fruit (Hylocereus polyrhizus): A green colorant for cotton fabric. Colorants, 2023, 2, 230–244. [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Silva, EM. Pitaya—Hylocereus undatus (haw). Exotic fruits. 2018, 339–349. [Google Scholar]

- Tel-Zur, N. Pitahayas: Introduction, agrotechniques, and breeding. In VII International Congress on Cactus Pear and Cochineal. 2010, 995, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrenosoğlu, Y.; Mertoğlu, K.; Bilgin, NA.; Misirli, A.; Özsoy, AN. Inheritance pattern of fire blight resistance in pear. Scientia horticulturae. 2019, 246, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Roman, RS.; Caetano, CM.; Ramírez, H.; Morales, J.G. Caracterización morfoanatómica y fisiológica de semilla sexual de pitahaya amarilla Selenicereus megalanthus (Haw. ) Britt & Rose. Revista de la Asociación Colombiana de Ciencias Biológicas. 2012, 24, 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, NM.; Nakagawa, J. Sementes: ciência, tecnologia e produção [Seeds: science, technology and production], 2012, Funep. 5th ed. Jaboticabal, Brazil.

- Shrivastava, P.; Kumar, R. Soil salinity: A serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation. Saudi journal of biological sciences. 2015, 22(2), 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizrahi, Y.; Nerd, A.; Sitrit, Y. New Fruits for arid climates. In Janick J, Whipkey A (eds.) Trends in new crops and new uses. 2002, ASHS Press, Alexandria. Virginia, United States.

- Tel-Zur, N.; Abbo, S.; Bar-Zvi, D.; Mizrahi, Y. Genetic relationships among Hylocereus and Selenicereus vine cacti (Cactaceae): Evidence from hybridization and cytological studies. Ann. Bot. 2004, 94, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parihar, P.; Singh, S.; Singh, R.; Singh, VP.; Prasad, SM. Effect of salinity stress on plants and its tolerance strategies: A review. Environmental science and pollution research, 2015, 22, 4056–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, AB.; Alencar, NLM. ; Gallão, MI.; Gomes Filho, E. Avaliação citoquímica durante a germinação de sementes de sorgo envelhecidas artificialmente e osmocondicionadas, sob salinidade [Cytochemical evaluation during the germination of artificial aged and primed sorghum seeds under salinity]. Rev. Ciênc. Agron. 2011, 42, 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.L.; Hsriprasanna, K.; and Chaudhari, V. Differential nutrients absorption an important tool for screening and identification of soil salinity tolerant peanut genotypes. Indian Journal of Plant Physiology. 2016, 21, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isayenkov, SV.; Maathuis, FJ. Plant salinity stress: Many unanswered questions remain. Frontiers in plant science, 2019, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, AK.; Das, AB. Salt tolerance and salinity effects on plants: a review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2005, 60, 324–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, MRR. ; Martins, CC.; Souza, GSF.; Martins, D. Influência do estresse hídrico e salino na germinação de Urochloa decumbens e Urochloa ruziziensis [Influence of saline and water stress on germination of Urochloa decumbens and Urochloa ruziziensis]. Biosci. J. 2012, 28, 537–545. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.; Farooq, S.; Hassan, W.; Ul-Allah, S.; Tanveer, M.; Farooq, M.; Nawaz, A. Drought stress in sunflower: Physiological effects and its management throughout breeding and agronomic alternatives. Agric Water Manag. 2018, 201, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaar-Moshe, L.; Blumwald, E.; Peleg, Z. Unique physiological and transcriptional shifts under combinations of salinity, drought, and heat. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Shivay, YS. Oxalic acid/oxalates in plants: From self-defence to phytoremediation. Current science. 2017, 1665–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, T.; Szalai, G.; Pál, M. Salicylic acid signalling in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakouhi, L.; Kharbech, O.; Massoud, MB.; Munemasa, S.; Murata, Y.; Chaoui, A. Oxalic acid mitigates cadmium toxicity in Cicer arietinum L. germinating seeds by maintaining the cellular redox homeostasis. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, L.M. Gibberellins. In: Srivastava, L.M. Plant growth and development Academic Press, New York, USA. 2022, pp. 172-181.

- Siebert, J.D.; Stewart, A.M. Influence of plant density on cotton response to mepiquat chloride application. Agron. J. 2006, 98, 1634–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavian, K.; Ghorbanli, M.; Kalantari, K.M. Role of salicylic acid in regulating ultraviolet radiation ınduced oxidative stress in pepper leaves. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 55, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung.

- Lehner, A.; Meimoun, P.; Errakhi, R.; Madiona, K.; Barakate, M.; Bouteau, F. Toxic and signaling effects of oxalic acid: natural born killer or natural born protector? Plant Signaling and Behavior, 2008, 3, 746–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lai, T.; Qin, G.; Tian, S. Response of jujube fruits to exogenous oxalic acid treatment based on proteomic analysis. Plant Cell Physiology. 2009, 50(2), 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Hwang, B.K. An important role of the pepper phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene (PAL1) in salicylic acid-dependent signalling of the defence response to microbial pathogens. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, QC.; Deng, XX.; Wang, JG. The effects of mepiquat chloride (DPC) on the soluble protein content and the activities of protective enzymes in cotton in response to aphid feeding and on the activities of detoxifying enzymes in aphids. BMC Plant Biology 2022, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, SMC. ; Paiva, EPD.; Torres, SB.; Neta, MLDS.; Leite, MDS.; Benedito, CP.; Albuquerque, CCD.; Sá, FVDS. Pre-germination treatments in pitaya (Hylocereus spp.) seeds to attenuate salt stress. Revista Ciência Agronômica, 2022, 53. [Google Scholar]

- ISTA, (2003): International Rules for Seed Testing. – International Seed Testing Association, Switzerland.

- Ergin, N.; Kulan, E.; Gözükara, M.; Kaya, M.; Çetin, Ş.; Kaya, MD. Response of germination and seedling development of cotton to salinity under optimal and suboptimal temperatures. Kahramanmaraş Sütçü İmam Üniversitesi Tarım ve Doğa Dergisi. 2021, 24, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, EA. Seed priming to alleviate salinity stress in germinating seeds. Journal of plant physiology. 2016, 192, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, AC.; Coutinho, G. Nitrogênio no desenvolvimento inicial de mudas de pitaya vermelha. Global Science Technology. 2019, 12, 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, MHDC. ; Sousa, GGD.; de Souza, MV.; de Ceita, ED.; Fiusa, JN.; Leite, KN. Emergence and biomass accumulation in seedlings of rice cultivars irrigated with saline water. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental. 2018, 22, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirra, KS.; Torres, SB.; Leite, MDS. ; Guirra, BS.; Nogueira Neto, FA.; Rêgo, AL. Phytohormones on the germination and initial growth of pumpkin seedlings under different types of water. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental. 2020, 24, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerchev, P.; van der Meer, T.; Sujeeth, N.; Verlee, A.; Stevens, CV.; Van Breusegem, F.; Gechev, T. Molecular priming as an approach to induce tolerance against abiotic and oxidative stresses in crop plants. Biotechnology advances. 2020, 40, 107503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, I.; Kuzucu, CO.; Ermis, S.; Öktem, G. Radicle emergence as seed vigour test estimates seedling quality of hybrid cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) cultivars in low temperature and salt stress conditions. Horticulturae, 2022, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, TA.; Gomes, GR.; Takahashi, LUSA. ; Urbano, MR.; Strapasson, E. Water and salt stress in germinating seeds of pitaya genotypes (Hylocereus spp.). African Journal of Agricultural Research, 2014, 9, 3610–3619. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, MD.; Akdoğan, G.; Kulan, EG.; Dağhan, H.; Sari, A. Salinity tolerance classification of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) and safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) by cluster and principal component analysis. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research. 2019, 17, 3849–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, J.; Pedreño, MA.; García-Carmona, F.; Muñoz, R. Characterization of the antiradical activity of betalains from Beta vulgaris L. roots. Phytochemical Analysis: An International Journal of Plant Chemical and Biochemical Techniques, 1998, 9, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamby Chik, C.; Bachok, S.; Baba, N.; Abdullah, A.; Abdullah, N. Quality characteristics and acceptability of three types of pitaya fruits in a consumer acceptance test. Journal of Tourism, Hospitality & Culinary Arts (JTHCA). 2011, 3, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- El-Keblawy, A.; Gairola, S.; Bhatt, A. Maternal salinity environment affects salt tolerance during germination in Anabasis setifera: A facultative desert halophyte. Journal of Arid Land. 2016, 8, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulan, EG.; Arpacıoğlu, A.; Ergin, N.; Kaya, MD. Evaluation of germination, emergence and physiological properties of sugar beet cultivars under salinity. Trakya University Journal of Natural Sciences. 2021, 22, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichienchot, S.; Jatupornpipat, M.; Rastall, RA. Oligosaccharides of pitaya (dragon fruit) flesh and their prebiotic properties. Food chem. 2010, 120, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamlıoğlu, NM.; Ünver, A.; Kadakal, Ç. Mineral content of pitaya (Hylocereus polyrhizus and Hylocereus undatus) seeds grown in Turkey. Erwerbs-Obstbau. 2021, 63, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paśko, P.; Galanty, A.; Zagrodzki, P.; Ku, YG.; Luksirikul, P.; Weisz, M.; Gorinstein, S. Bioactivity and cytotoxicity of different species of pitaya fruits–A comparative study with advanced chemometric analysis. Food Bioscience. 2021, 40, 100888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, ŞH. ; Gündeşli, MA.; Urün, I.; Kafkas, S.; Kafkas, NE.; Ercisli, S.; Ge, C.; Mlcek, J.; Adamkova, A. Nutritional analysis of red-purple and white-fleshed pitaya (Hylocereus) species. Molecules. 2022, 27, 808. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, JS.; García-Sánchez, F.; Rubio, F.; García, AL.; Martínez, V. The importance of K+ in ameliorating the negative effects of salt stress on the growth of pepper plants. European Journal of Horticultural Science. 2010, 75, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, SH.; Niu, YJ.; Zhai, H.; Han, N.; Du, YP. Effects of alkaline stress on organic acid metabolism in roots of grape hybrid rootstocks. Scientia Horticulturae. 2018, 227, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çolak, AM.; Mertoğlu, K.; Alan, F.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Bulduk, İ.; Akbel, E.; Kahramanoğlu, I. Screening of naturally grown european cranberrybush (Viburnum opulus L.) genotypes based on physico-chemical characteristics. Foods. 2022, 11, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

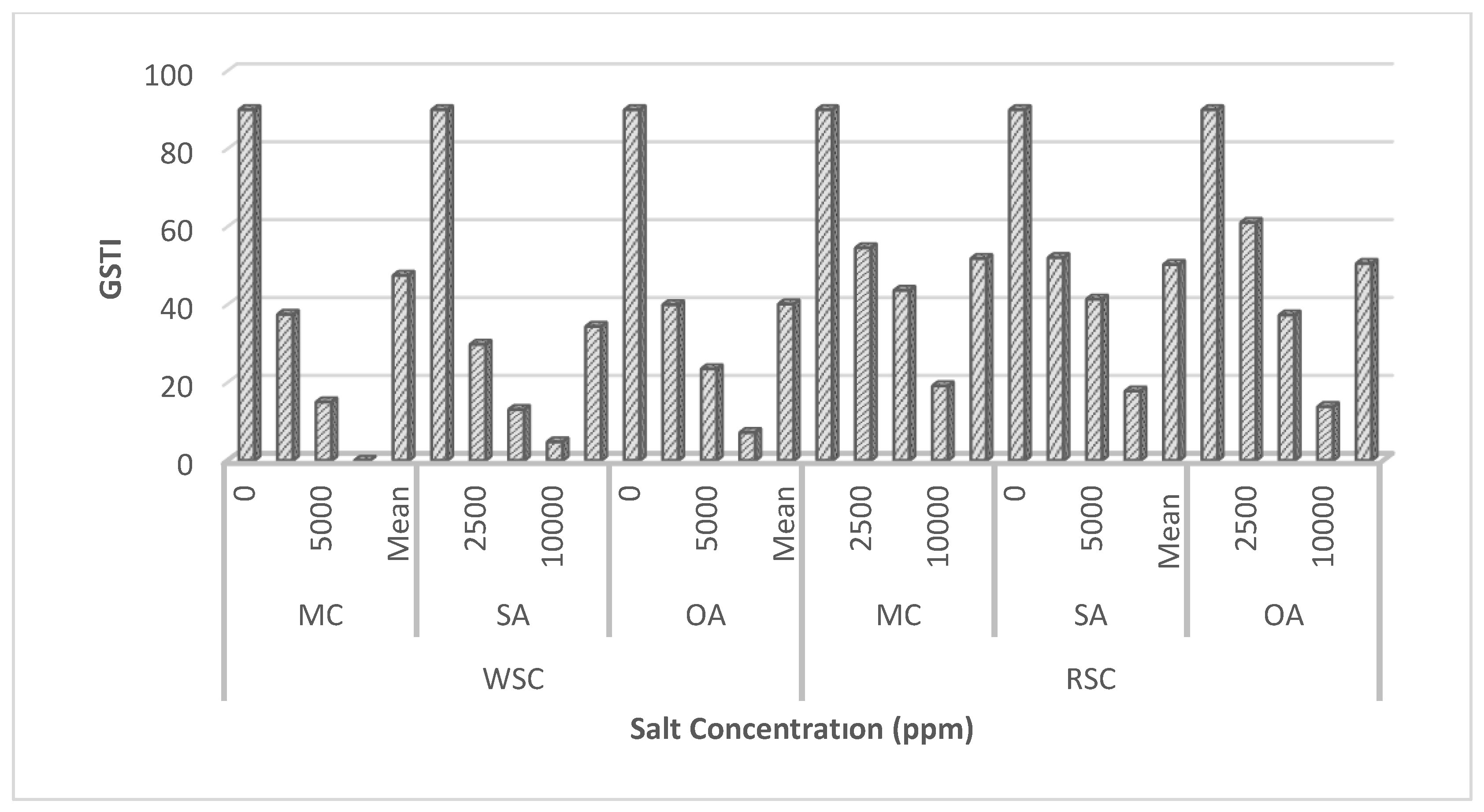

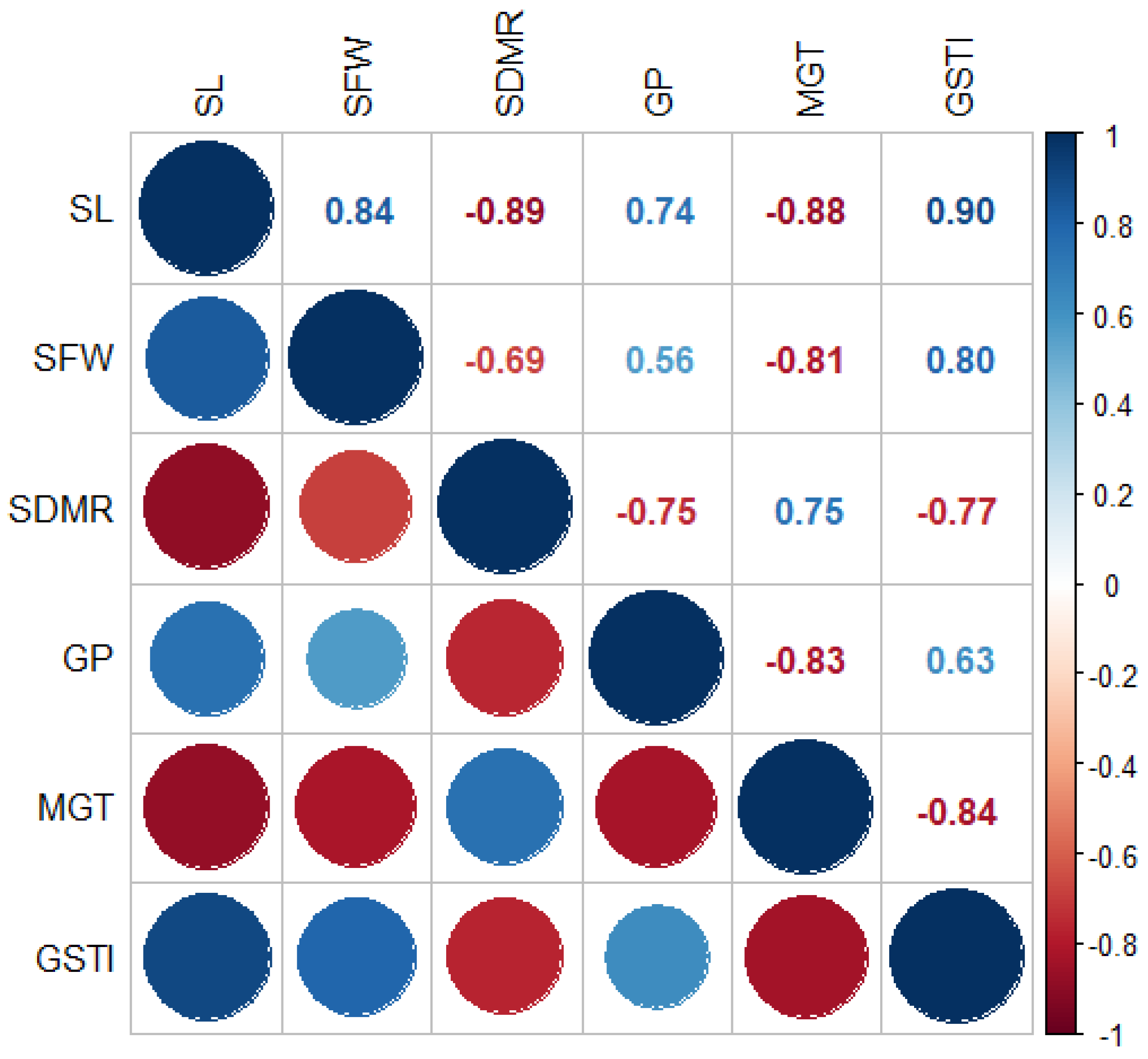

| Flesh Color (FC) | Germination (%) | MGT (day) | Shoot length (cm) | Fresh seedling weight (mg) | Seedling dry matter ratio (%) | GSTI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 81.17 b | 11.24 a | 27.90 b | 12.29 b | 4.44 b | 36.08 b |

| Red | 85.33 a | 7.33 b | 31.49 a | 21.23 a | 4.65 a | 54.91 a |

| Salt Concentrations (SC) | ||||||

| Control | 98.44 a | 4.74 d | 41.56 a | 22.85 a | 2.87 d | 100.0 a |

| 2500 ppm | 90.00 b | 7.06 c | 35.78 b | 20.76 b | 3.54 c | 51.32 b |

| 5000 ppm | 89.50 b | 9.80 b | 26.18 c | 14.64 c | 4.45 b | 25.97 c |

| 10 000 ppm | 55.06 c | 15.55 a | 15.26 d | 8.79 d | 7.33 a | 4.68 d |

| Plant Growth Regulators (PGRs) | ||||||

| MC | 83.54 ns | 9.16 b | 30.09 ns | 16.96 a | 4.46 ns | 46.05 b |

| SA | 82.21 | 9.62 a | 29.37 | 16.28 b | 4.58 | 43.22 c |

| OA | 84.00 | 9.08 b | 29.63 | 17.04 a | 4.60 | 47.21 a |

| ANOVA Significance levels | ||||||

| FC | ** | *** | *** | *** | * | *** |

| SC | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| PGR | ns | * | ns | ** | ns | *** |

| FC*SC | *** | *** | ns | *** | *** | ** |

| FC*PGR | ns | ns | ns | * | *** | *** |

| SC*PGR | * | ns | ns | ** | *** | *** |

| FC*SC*PGR | ns | ns | ns | ** | ** | *** |

| Germination percentage (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flesh Color | Salt Concentrations | Hormones | |||

| MC | SA | OA | Mean | ||

| White | 0 | 97.67 | 98.33 | 98.00 | 98.00A |

| 2500 | 94.67 | 89.33 | 93.33 | 92.44A | |

| 5000 | 94.67 | 92.33 | 93.33 | 93.44A | |

| 10000 | 39.33 | 34.27 | 48.67 | 40.76B | |

| Mean | 81.58 | 78.57 | 83.33 | 81.16B | |

| Red | 0 | 98.67 | 99.33 | 98.67 | 98.89A |

| 2500 | 83.33 | 88.67 | 90.67 | 87.56B | |

| 5000 | 88.00 | 89.33 | 79.33 | 85.56B | |

| 10000 | 72.00 | 66.00 | 69.92 | 69.31C | |

| Mean | 85.50 | 85.83 | 84.65 | 85.33A | |

| Means of Flesh Colors | 0 | 98.17A | 98.83A | 98.33A | 98.44A |

| 2500 | 89.00A | 89.00A | 92.00A | 90.00B | |

| 5000 | 91.33A | 90.83A | 86.33A | 89.50B | |

| 10000 | 55.67AB | 50.14B | 59.29A | 55.03C | |

| Mean | 83.54 | 82.20 | 83.99 | 83.24 | |

| Mean germination time (day) | |||||

| Flesh Color | Salt Concentrations | Hormones | |||

| MC | SA | OA | Mean | ||

| White | 0 | 5.31 | 5.25 | 5.30 | 5.29D |

| 2500 | 8.20 | 8.79 | 7.958 | 8.35C | |

| 5000 | 11.78 | 12.32 | 11.90 | 12.00B | |

| 10000 | 19.51 | 20.10 | 18.39 | 19.33A | |

| Mean | 11.22 | 11.61 | 10.89 | 11.24A | |

| Red | 0 | 4.20 | 4.25 | 4.15 | 4.20 D |

| 2500 | 5.73 | 6.11 | 5.46 | 5.77 C | |

| 5000 | 7.18 | 7.54 | 8.06 | 7.59 B | |

| 10000 | 11.28 | 12.56 | 11.46 | 11.77A | |

| Mean | 7.10 | 7.62 | 7.28 | 7.33B | |

| Means of Flesh Colors | 0 | 4.75 | 4.75 | 4.72 | 4.74D |

| 2500 | 7.02 | 7.45 | 6.71 | 7.06C | |

| 5000 | 9.48 | 9.93 | 9.98 | 9.78B | |

| 10000 | 15.40B | 16.33A | 14.92B | 15.55A | |

| Mean | 9.16 | 9.62 | 9.08 | 9.29 | |

| Shoot length (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flesh Color | Salt Concentrations | Plant Growth Regulator | |||

| MC | SA | OA | Mean | ||

| White | 0 | 39.83A | 38.83A | 41.00A | 39.89A |

| 2500 | 33.00A | 31.92A | 33.92A | 32.94B | |

| 5000 | 25.00A | 25.17A | 24.00A | 24.72C | |

| 10000 | 14.67A | 13.33A | 14.17A | 14.06D | |

| Mean | 28.12 | 27.31 | 28.27 | 27.90B | |

| Red | 0 | 43.67A | 43.83A | 42.17A | 43.22A |

| 2500 | 39.75A | 39.75A | 36.33B | 38.61B | |

| 5000 | 29.08A | 25.50B | 28.33AB | 27.64C | |

| 10000 | 15.75A | 16.58A | 17.08A | 16.47D | |

| Mean | 32.06 | 31.42 | 30.98 | 31.48A | |

| Means of Flesh Colors | 0 | 41.75 | 41.33 | 41.58 | 41.56A |

| 2500 | 36.37 | 35.83 | 35.12 | 35.78B | |

| 5000 | 27.04 | 25.33 | 26.17 | 26.18C | |

| 10000 | 15.21 | 14.96 | 15.62 | 15.26D | |

| Mean | 30.09 | 29.36 | 29.62 | 29.69 | |

| Fresh seedling weight (mg) | |||||

| Flesh Color | Salt Concentrations | Plant Growth Regulator | |||

| MC | SA | OA | Mean | ||

| White | 0 | 16.89A | 16.50A | 17.06A | 16.82A |

| 2500 | 14.71A | 14.18A | 14.48A | 14.45B | |

| 5000 | 11.39A | 11.97A | 10.51A | 10.96C | |

| 10000 | 7.07A | 6.71A | 6.97A | 6.92D | |

| Mean | 12.51A | 12.09A | 12.25A | 12.29B | |

| Red | 0 | 28.94A | 29.03A | 28.69A | 28.89A |

| 2500 | 28.28A | 25.58B | 27.36A | 27.07B | |

| 5000 | 18.89A | 16.14B | 19.92A | 18.32C | |

| 10000 | 9.53B | 11.11AB | 11.31A | 10.65D | |

| Mean | 21.41A | 20.46B | 21.82A | 21.23A | |

| Means of Flesh Colors | 0 | 22.92A | 22.76A | 22.87A | 22.85A |

| 2500 | 21.50A | 19.88B | 20.92A | 20.76B | |

| 5000 | 15.14A | 13.56B | 15.21A | 14.64C | |

| 10000 | 8.30A | 8.91A | 9.14A | 8.78D | |

| Mean | 16.96A | 16.28B | 17.04A | 16.76 | |

| Seedling dry matter ratio (%) | |||||

| Flesh Color | Salt Concentrations | Plant Growth Regulator | |||

| MC | SA | OA | Mean | ||

| White | 0 | 2.99A | 3.01A | 2.97A | 2.99D |

| 2500 | 3.46A | 3.66A | 3.78A | 3.64C | |

| 5000 | 4.51A | 4.39A | 3.90B | 4.27B | |

| 10000 | 7.06A | 7.37A | 6.19B | 6.88A | |

| Mean | 4.51A | 4.61A | 4.21B | 4.44B | |

| Red | 0 | 2.76A | 2.77A | 2.69A | 2.74D |

| 2500 | 3.10B | 3.48AB | 3.76A | 3.45C | |

| 5000 | 4.90A | 4.54A | 4.46A | 4.63B | |

| 10000 | 8.00A | 7.43B | 7.92AB | 7.78A | |

| Mean | 4.69A | 4.56A | 4.71A | 4.65A | |

| Means of Flesh Colors | 0 | 2.88A | 2.89A | 2.83A | 2.87D |

| 2500 | 3.28B | 3.57AB | 3.77A | 3.54C | |

| 5000 | 4.71A | 4.47AB | 4.18B | 4.45B | |

| 10000 | 7.53A | 7.40A | 7.06B | 7.34A | |

| Mean | 4.46 | 4.58 | 4.60 | 4.55 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).