Submitted:

16 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Hydrodynamic Cavitation Passive Control Methods

| Investigators | Type of Work | Control Method | Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crimi (1970) [25] | Experiment | Sweep angle of hydrofoil | Alleviating problem of cavitation-induced erosion. |

| Kawanami et al. (1997) [22] | Experiment | Obstacles | Reduction in cavitation-induced noise and hydrofoil drag, suppression of re-entrant jet. |

| Pham et al. (1999) [53] | Experiment | Obstacles | Reduction in amplitude of cavitation instabilities. |

| Hofmann et al. (2001) [26] | Experiment | Obstacles | Reduction in cavitation-induced noise. |

| Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2005) [28] | Experiment | Surface roughness | Rearranging cavitation cycle in sheet cavity structure. |

| Choi2007 et al. (2005) [27] | Experiment | J-Grooves | Improvement of suction performance of the inducer. |

| Ausoni et al. (2007) [55] | Experiment | Blunt trailing edge | Reduction in vortex shedding frequencies. |

| Kim et al. (2010) [29] | Experiment | Obstacles | Mitigation in cavity instability. |

| Ausoni et al. (2012) [56] | Experiment | Blunt trailing edge | Obtaining more organized vortex shedding. |

| Danlos et al. (2014) [30] | Experiment | Surface roughness/Grooves | Mitigation in flow unsteadiness linked with cloud cavitation shedding, reduction in cavity sheet length. |

| Danlos et al. (2014) [31] | Experiment | Surface roughness/Grooves | Reduction in cloud cavitation shedding, reduction in cavity sheet length. |

| Ganesh et al. (2015) [57] | Experiment | Obstacles | Observation of low speed of sound once the cavity length crosses the obstacle. |

| Onishi et al. (2017) [58] | Experiment | Hydrophilic and hydrophobic coatings | Reduction in growth of cavitation at small attack angles. |

| Che et al. (2017) [59] | Experiment | Micro vortex generators | Potential to control the attached cavitation dynamics. |

| Hao et al. (2018) [60] | Experiment | Surface roughness | Changing the cavity structure, velocity and vorticity distribution of the cloud cavitation. |

| Zhang et al. (2018) [61] | Experiment | Obstacles | Reduction of strength and direction of the transient re-entrant jet. |

| Custodio et al. (2018) [62] | Experiment | Wavy leading edge | Lift coefficient for simple hydrofoil was comparable to or greater than that of the hydrofoils with wavy leading edges. |

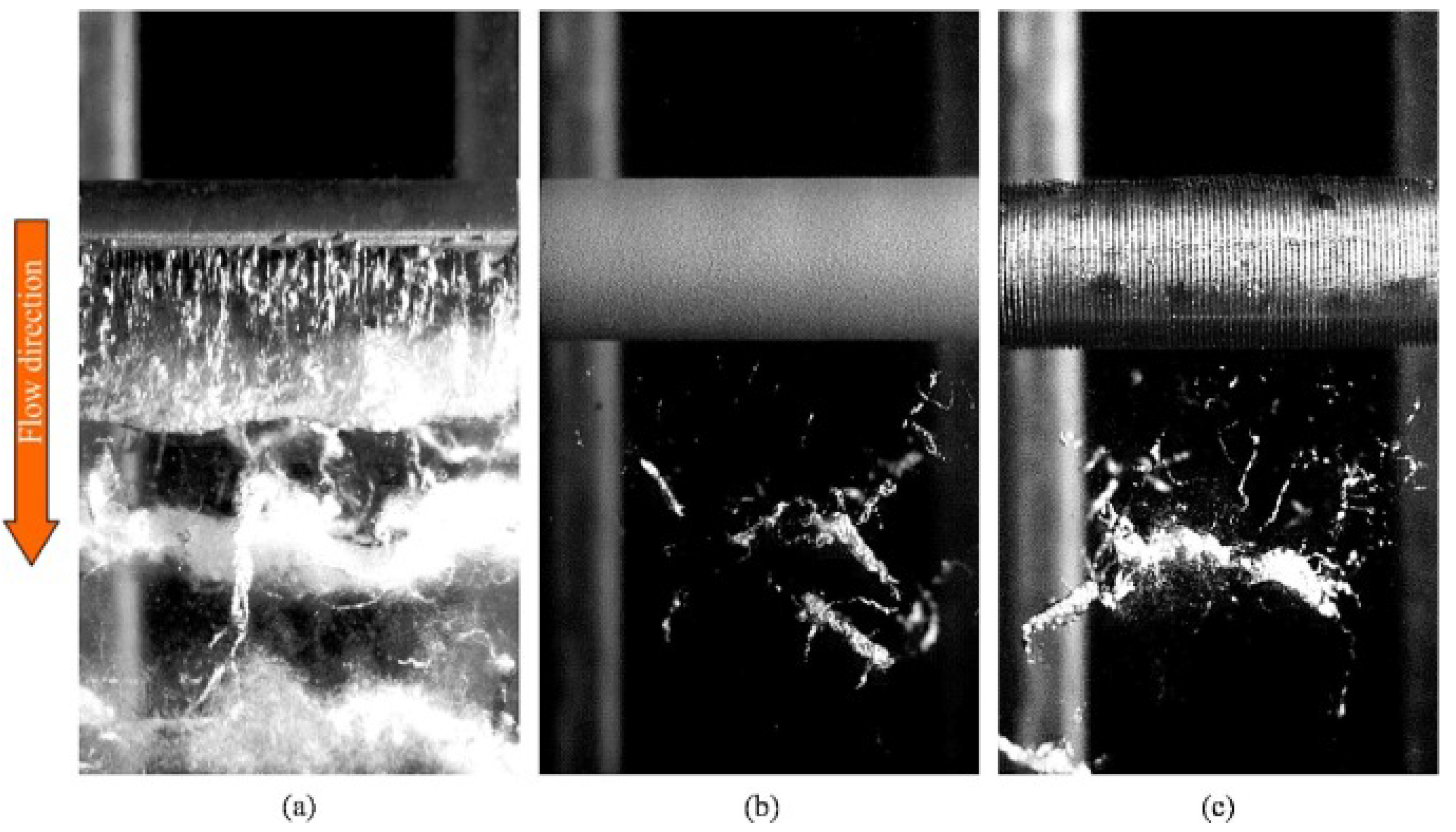

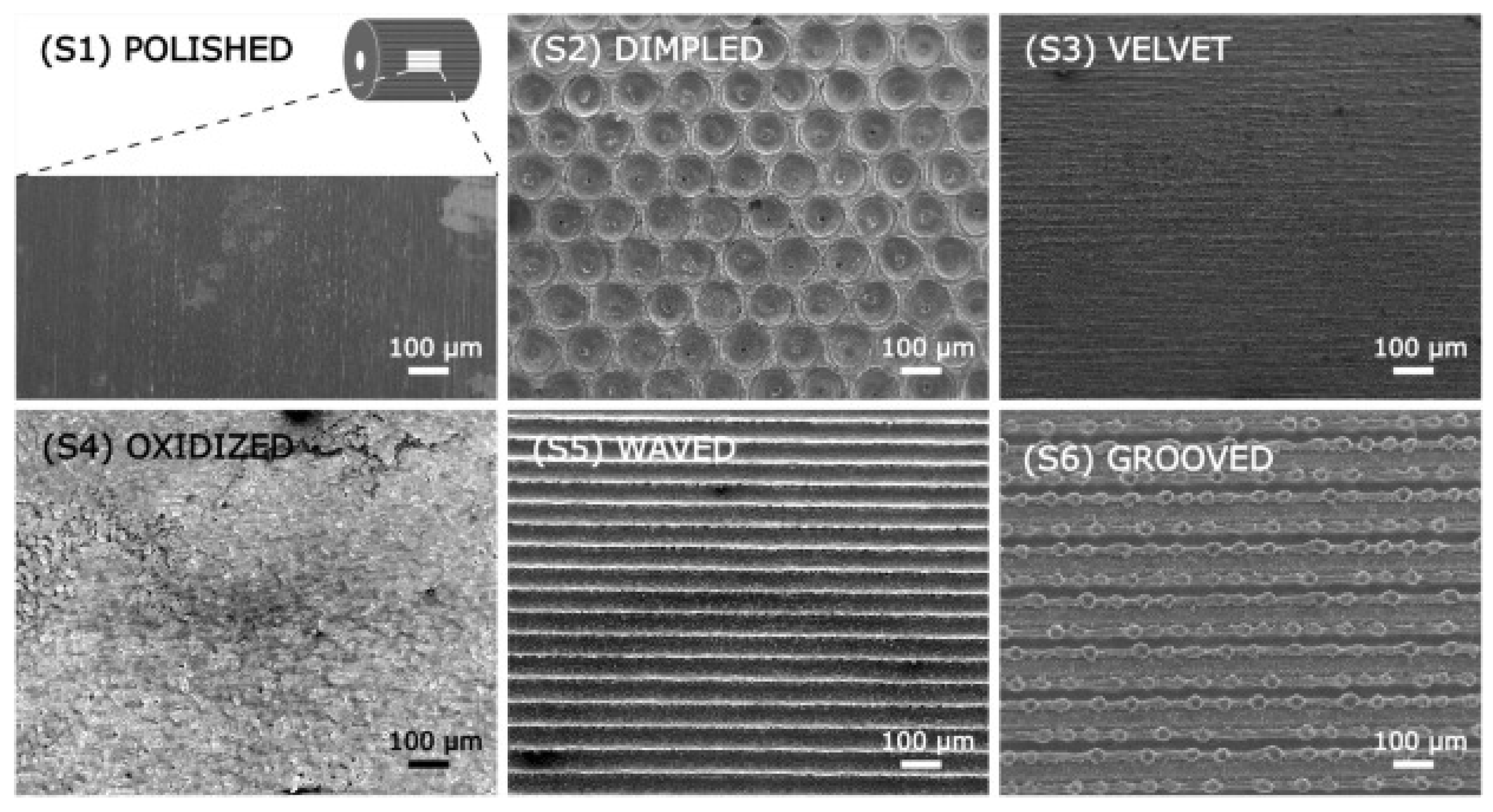

| Petkovsek et al. (2018) [63] | Experiment | Surface topographies: dimpled, velvet, oxidized, waved, grooved | Mitigation in cavitation on the cylinder using an appropriate laser-texturing parameter. |

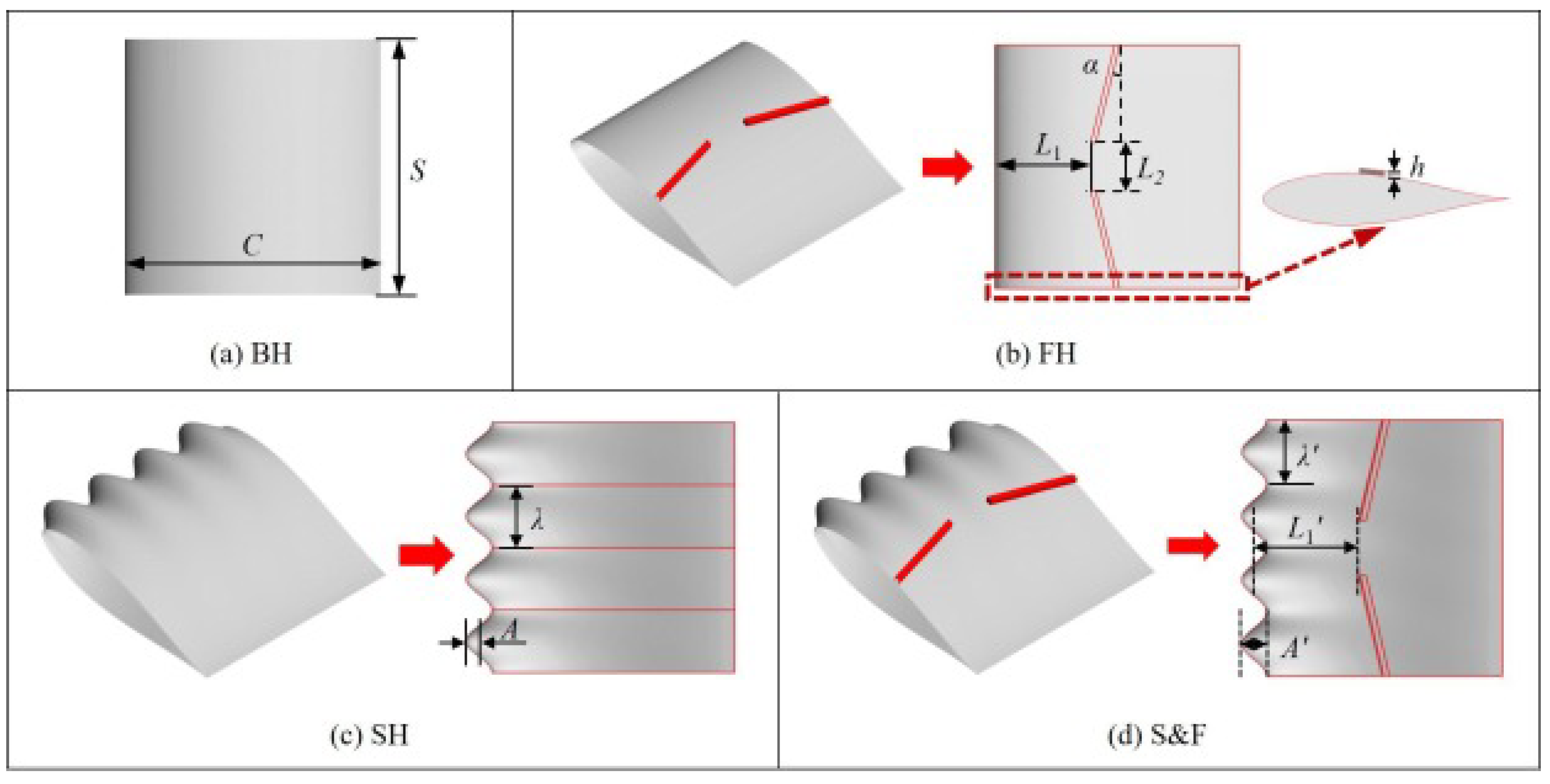

| Kadivar et al. (2019b) [64] | Experiment | Wedge-type vortex generator | Mitigation in wall-pressure peaks and turbulent velocity fluctuations. |

| Che et al. (2019) [65] | Experiment | Micro vortex generators | Suppression of laminar separation under non-cavitating conditions, fixing cavitation inception causing. |

| Che et al. (2019) [66] | Experiment | Micro vortex generators | Obtaining more stable sheet cavitation and cloud cavity shedding. |

| Che et al. (2019) [67] | Experiment | Micro vortex generators | Obtaining more stable sheet cavitation and cloud cavity shedding. |

| Amini et al. (2019) [37] | Experiment | Winglets | Increasing radius of the tip vortex and delay initial inception of the cavitation. |

| Kadivar et al. (2020) [36] | Experiment | Wedge-type vortex generator | Mitigation in wall-pressure peaks and turbulent velocity fluctuations, mitigation of cloud cavity shedding. |

| Kadivar et al. (2020) [40] | Experiment | Cylindrical type of vortex generators | Mitigation in cloud cavitation instabilities and the pressure pulsations. |

| Qiu et al. (2020) [69] | Experiment | Micro vortex generators | Reduction in maximum pressure fluctuation by 32%, reduction in acoustic power by 10.8 dB, mitig erosion at the leading edge. |

| Petkovsek et al. (2020) [70] | Experiment | Surface topographies: dimpled, velvet, oxidized, waved, grooved | Mitigation in cavitation on the cylinder using an appropriate laser-texturing parameter. |

| Chen et al. (2020) [71] | Experiment | Leading edge roughness | Control the formation of the incipient cavitation, delay in maximum lift-to-drag ratio angle. |

| Huang et al. (2020) [72] | Experiment | Vortex generator (VG) | Changing of propeller cavitation, reduction in the pressure fluctuations. |

| Cheng et al. (2020) [73] | Experiment | Overhanging grooves | Suppression in tip-leakage vortex cavitation. |

| Svennberg et al. (2020) [74] | Experiment | Surface roughness | Reduction in cavitation number for tip vortex cavitation inception by 33%, increasing of drag force by 2%. |

| Kadivar et al. (2021) [76] | Experiment | Hemispherical vortex generators | Mitigation in amplitude of the pressure pulsations. |

| Arab et al. (2022) [78] | Experiment | Leading and trailing edge flaps | Enhancement of lift coefficient, reduction in cavitation volume. |

| Kadivar et al. (2024) [81] | Experiment | Biomimetic riblets | Reduction in lift force fluctuations, mitigation in cavitation-induced vibration amplitudes by about 41% and 43% for sawtooth and scalloped riblets, respectively. |

| Nichik et al. (2024) [82] | Experiment | Surface morphology/roughness | Suppression of cavity structure on cylinder, affecting on turbulence structure of the wake flow, including the mean velocity, dispersion and higher-order moments of turbulent fluctuations. |

| Lin et al. (2024) [48] | Experiment | Bio-inspired riblets | Reduction of noise at low frequency domain, reduction in the re-entrant jet momentum and unsteady cavity. |

| Li et al. (2025) [86] | Experiment | Spanwise obstacles | Suppression of development of unsteady cavitation, mitigation in cavitation-induced noise, reduction in maximum negative torque. |

| Kumar et al. (2025) [83] | Experiment | Sawtooth and scalloped mesoscale riblets | Reduction in cavitation-induced vibrations of the cylinder. |

| Kumar et al. (2025) [87] | Experiment | Bio-inspired riblets | Reduction of noise at low frequency domain, reduction in the re-entrant jet momentum and unsteady cavity. |

| Çelik et al. (2025) [90] | Experiment | Leading-edge tubercle and surface corrugation | Lowest cavitation area and period for tubercled hydrofoil by 70% and 50% of those of baseline and corrugated hydrofoils, respectively. |

| Kadivar et al. (2020) [38] | Exp/Num | Wedge-type vortex generator/Cylindrical type vortex generator | Changing large-scale cloud cavitation to a quasi-stable attached cavity, enhancement of lift to drag ratio, mitigation in wall-pressure peaks and turbulent velocity fluctuations. |

| Zhao et al. (2021) [77] | Exp/Num | Tandem obstacles | More resistance against the incipient and development of leading-edge cavities. |

| Chen et al. (2021) [75] | Exp/Num | Micro vortex generator (mVG) | mVG-1 configuration can promote the earlier inception cavitation, mVG-2 configuration can delay the inception. |

| Qiu et al. (2023a) [80] | Exp/Num | Micro vortex generator (mVG) | Improvement of lift-to-drag ratio, enhancement of stability of the flow field. |

| Qiu et al. (2024a) [84] | Exp/Num | Micro vortex generator (mVG) | Mitigation of unsteady cavity structure, Improvement of lift-to-drag ratio. |

| Qiu et al. (2024b) [85] | Exp/Num | Slits | Reduction in primary frequency of cavitation pulsations by 48.5%, diminishing momentum of the re-entrant jet. |

| Zhu et al. (2025) [89] | Exp/Num | Vortex generators: micro-VG and large-VG | Alteration of pressure fluctuation period, reduction of main frequency amplitude, reduction in erosion risk on the hydrofoil. |

| Xue et al. (2025) [91] | Exp/Num | Bionic leading-edge protuberances | Suppression in formation of large vortices near the hydrofoil’s leading edge. |

| Zhao et al. (2010) [41] | Numerical | Obstacles | Enhancement of lift to drag ratio. |

| Javadi et al. (2017) [42] | Numerical | Vortex generator | Mitigation of force fluctuations and cloud cavity structures. |

| Kadivar et al. (2017) [43] | Numerical | Wedge-type vortex generator | Mitigation in wall-pressure peaks and turbulent velocity fluctuations on the hydrofoil. |

| Kadivar et al. (2018) [34] | Numerical | Wedge-type vortex generator | Changing large-scale cloud cavitation to a quasi-stable attached cavity, enhancement of lift to drag ratio, mitigation in wall-pressure peaks and turbulent velocity fluctuations. |

| Kadivar et al. (2018) [35] | Numerical | Wedge-type vortex generator | Increasing of lift to drag ratio, mitigation in wall-pressure peaks and turbulent velocity fluctuations. |

| Kamikura et al. (2018) [33] | Numerical | Asymmetric slits | Mitigation in cavitation instabilities. |

| Zhao and Wang (2019) [44] | Numerical | Bionic fin-fin structure | Increasing of lift to drag ratio using the bionic structure, mitigation in turbulent kinetic energy. |

| Kadivar et al. (2019) [39] | Numerical | Cylindrical type of vortex generators | Mitigation in unsteady behavior of the cloud cavitation, obtaining more stable attached cavity on the foil’s surface. |

| Li et al. (2021) [45] | Numerical | Wavy leading-edge | Reduction in cavitation volume by approximately 30%, mitigation in pressure amplitude by approximately 60%. |

| Lin et al. (2021) [46] | Numerical | Arc obstacles | Obtaining more stabilization in cavitation behavior, inhibiting evolution of cavitation through the effects of the arc obstacles. |

| Jia et al. (2022) [47] | Numerical | V-shaped groove | Reduction in average cavitation volume during a cavitation cycle by 17.46%, decreasing average dipole noise by 5.07% and average quadrupole noise by 6.86%. |

| Yang et al. (2024) [49] | Numerical | Two bionic structures | Reduction in total volume of cavitation by 43%, enhancement of stability of the flow field, reduction in standard deviation of the pressure coefficient by 46%. |

| Kumar et al. (2025) [88] | Numerical | Surface cavity | Enhancement of about 7% and 3.1% in lift to drag ratio. |

| Usta et al. (2025) [50] | Numerical | Leading-edge tubercles and surface corrugations | Obtaining delay of stall and less cavitation area for the tubercled hydrofoil. |

| Velayati et al. (2025) [51] | Numerical | Semi-spherical VG | Reduction in cloud cavitation shedding frequency, increasing frequency of cavity shedding by 19.4% and increasing lift-to-drag ratio by 2.5% for semi-spherical VG located near trailing edge. |

| Biswas et al. (2025) [52] | Numerical | Triangular slot | Avoiding stalling for the hydrofoil with slot, better control of cavitation for modified hydrofoil at lower cavitation numbers. |

3. Hydrodynamic Cavitation Active Control Methods

| Investigators | Type of Work | Control Method | Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arndt et al. (1995) [92] | Experiment | Air injection through small holes | Mitigation of cavitation-induced erosion. |

| Reisman et al. (1997) [93] | Experiment | Air injection | Reduction in the magnitude of pressure pulsations. |

| Pham et al. (1999) [53] | Experiment | Air injection through a slit | Reduction in amplitude of the cavitation instabilities. |

| Hofmann et al. (2001) [26] | Experiment | Air injection | Mitigation of cavitation-induced erosion. |

| Ceccio et al. (2010) [97] | Experiment | Bubble and gas injection | Reduction in friction drag. |

| Hsiao et al. (2010) [95] | Experiment | Polymer injection | Delaying the cavitation inception. |

| Chahine et al. (2012) [96] | Experiment | Polymer injection | Delaying the cavitation inception. |

| Wang et al. (2018) [100] | Experiment | Gas injection | Effect on the velocity and vorticity distributions. |

| Wang et al. (2018) [101] | Experiment | Air injection | Promotion in growth of attached cavity and size of the cloud cavity. |

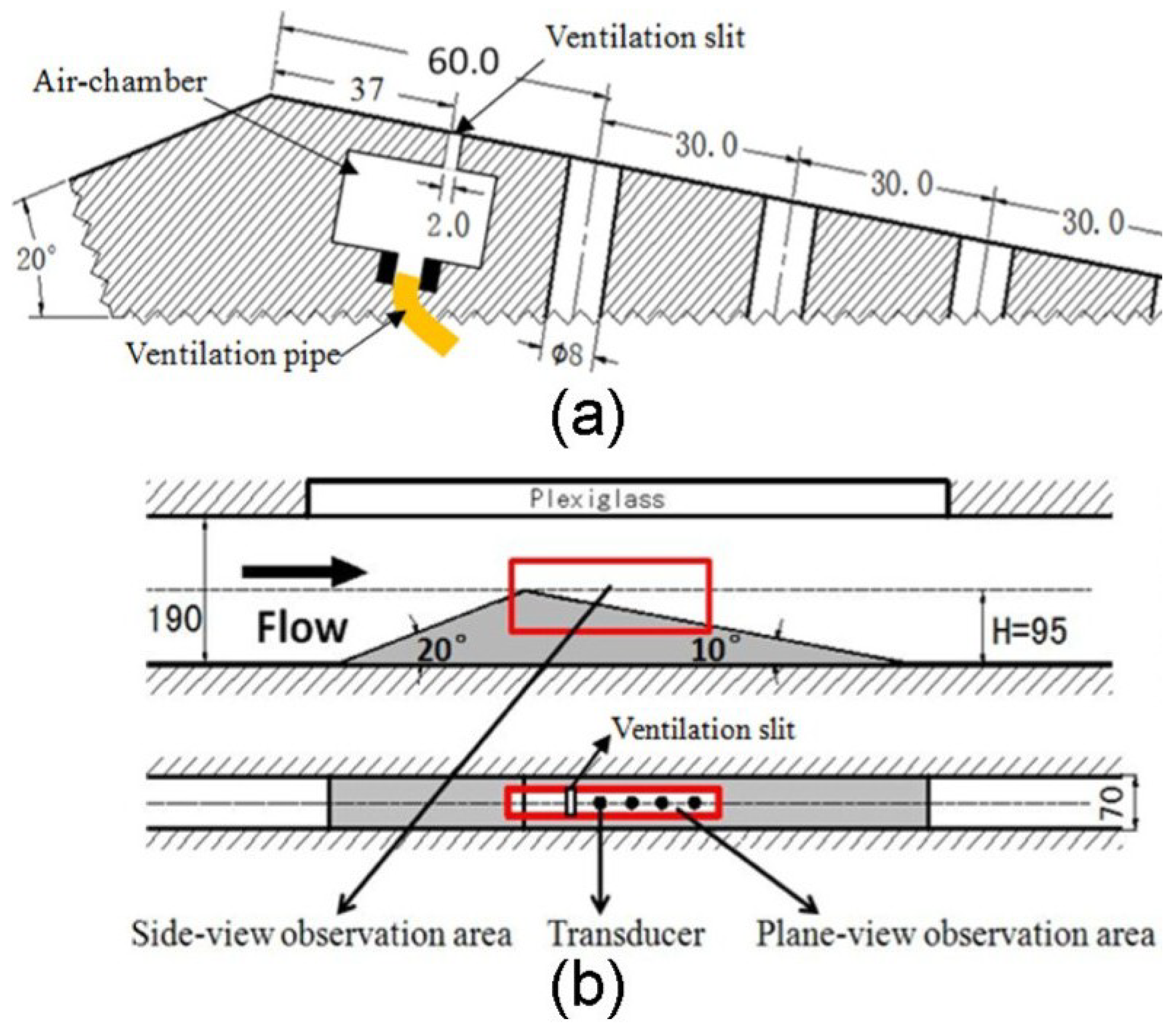

| Timoshevskiy et al. (2018) [102] | Experiment | Water injection | Mitigation in cavitation volume and amplitude of pressure pulsations. |

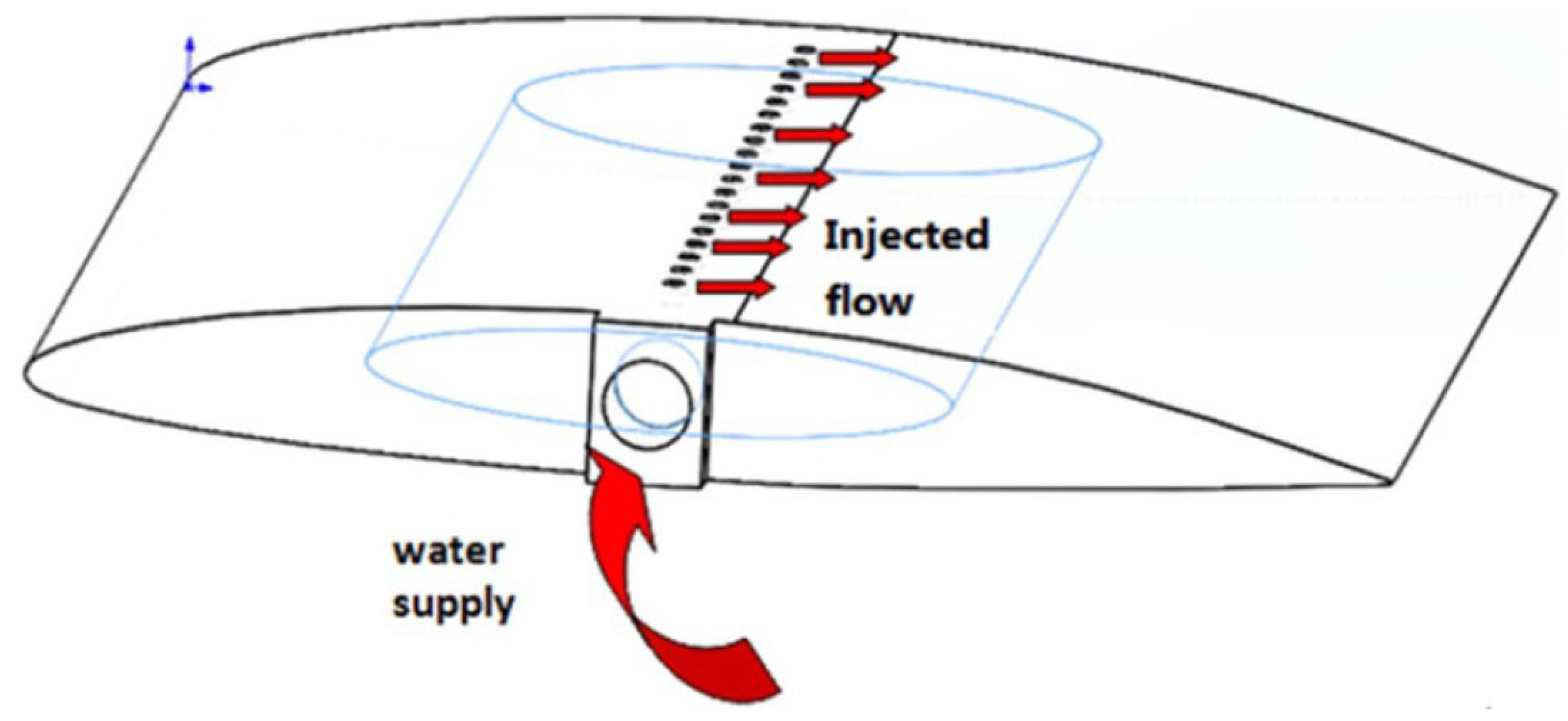

| Wang et al. (2020) [103] | Experiment | Water injection | Block the re-entrant jet. |

| Malekshah et al. (2023) [110] | Experiment | Air injection | Significant effect on the cavitation dynamic features. |

| Hilo et al. (2024) [111] | Experiment | Air injection | Reduction in length of the vapor sheet. |

| Singh et al. (2024) [112] | Experiment | Air injection | Optimizing cavitation efficiency in the converging–diverging nozzle. |

| Hilo et al. (2025) [116] | Experiment | Air injection | Less fluctuation in sheet cavity pulsation, Increasing sound pressure level at lower frequencies. |

| Zhang et al. (2009) [94] | Numerical | Polymer injection | Reduction in maximum tangential velocity along the vortex, delaying cavitation inception. |

| Wang et al. (2017) [99] | Numerical | Water injection | Increasing velocity gradient in boundary layer, reduction in flow separation, mitigation of re-entrant jet. |

| Wang et al. (2020) [104] | Numerical | Water injection holes | Potential for cavitation suppression, higher pressure at leading edge with reducing of lift in some condition. |

| Sun et al. (2020) [105] | Numerical | Ventilation | Reduction in turbulence intensity and turbulence integral scale in the wake region. |

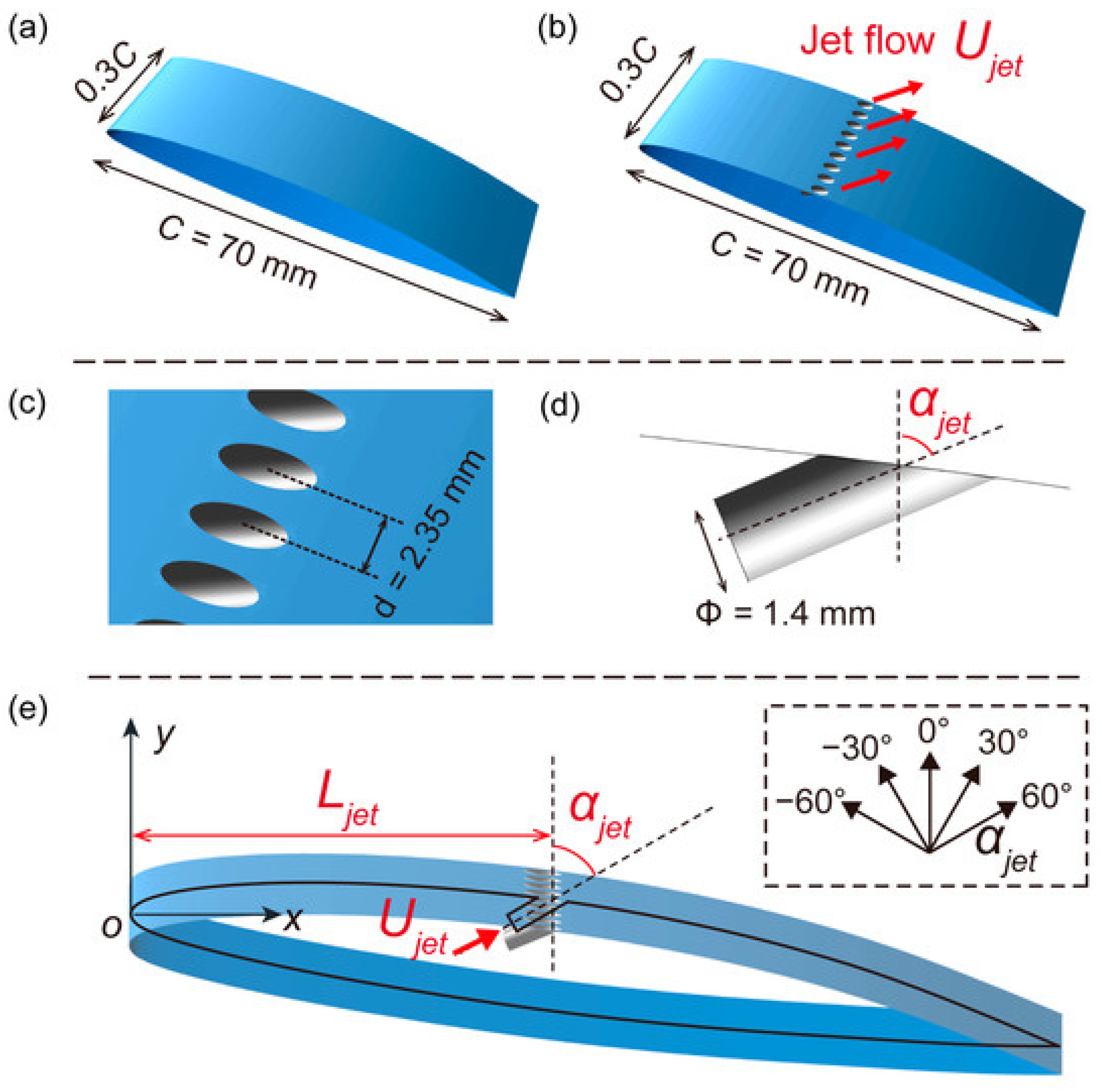

| De Giorgi et al. (2020) [106] | Numerical | Single synthetic jet actuator | Reduction in average vapor and average torsional load by 34.6% and 17.8%, respectively. |

| Yan et al. (2022) [107] | Numerical | Active jet | Increasing lift-drag ratio by 11.4% and reduction in cavitation volume about 30% with optimal jet scheme. |

| Luo et al. (2022) [108] | Numerical | Ventilation | Interaction between turbulence and gas-liquid interfacial fluctuations for the ventilated wake flow. |

| Gu et al. (2023) [109] | Numerical | Bionic jet-shark gill slit jet structure | Reduction in time-averaged volume fraction by 46% compared at jet position of 0.6C, improvement of lift-to-drag ratio. |

| Wang et al. (2024) [113] | Numerical | Water injection | Reduction in cavitation volume by 49.34% and lift–drag ratio enhancement by 8.55% for water injection at 0.30C and jet of 60 degrees. |

| Li et al. (2024) [114] | Numerical | Water injection combined with barchan dune vortex generators | Reduction in cavitation volume, increasing lift-to-drag ratio by 64.54% for the hydrofoil using water injection combined with barchan dune VG. |

| Li et al. (2025) [115] | Numerical | Water injection | Increasing lift-to-drag ratios for configurations H019C, H030C, and H045C by 0.30%, 8.44%, and 12.30%, respectively. |

| Ji et al. (2025) [117] | Numerical | Water injection | Reduction in drag coefficient by 3.5%, reduction of 15.40% in the maximum circumferential velocity of the tip leakage vortex. |

| Wang et al. (2025) [118] | Numerical | Piezoelectric actuators | Changing cavity shedding mode from a large-scale shedding near the leading edge to a small-scale shedding. |

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knapp, R.T.; Daily, J.W.; Hammitt, F.G. Cavitation; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1970.

- Brennen, C. E. Cavitation and bubble dynamics. Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Reisman, G.; Wang, Y.; Brennen, C. Observations of shock waves in cloud cavitation. J. Fluid Mech. 355 pp. 255–283 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Blake, W.K. Mechanics of Flow-Induced Sound and Vibration; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; Volumes I & II.

- Franc, J.-P.; Michel, J.-M. Fundamentals of cavitation. Springer, 2005.

- Kuiper, G. Theoretical and experimental investigations on the flow around cavitating hydrofoils. PhD Thesis, Delft University of Technology, 1981.

- Arndt, R.E.A. Cavitation in fluid machinery and hydraulic structures. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 34, 143–175 (2002).

- Dular, M.; Bachert, B.; Stoffel, B.; Sirok, B. Relationship between cavitation structures and cavitation damage. Wear 2004, 257, 1176–1184. [CrossRef]

- Patella, R.; Choffat, T.; Reboud, J.; Archer, A. Mass loss simulation in cavitation erosion: Fatigue criterion approach. Wear 2013, 300, 205–215. [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, G. Large eddy simulation of turbulent vortex-cavitation interactions in transient sheet/cloud cavitating flows. Comput. Fluids 2014, 92, 113–124. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Kadivar, E.; Moctar, O.; Neugebauer, J.; Schellin, T. Experimental investigation on the effect of fluid–structure interaction on unsteady cavitating flows around flexible and stiff hydrofoils. J. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 083308. [CrossRef]

- Ganz, S. 2012, Cavitation: causes, effects, mitigation and application, friction and wear of materials, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Hartford, Connecticut, USA.

- Oh, J., Lee, H.B., Shin, K., Lee, C., Rhee, S.H., Suh, J.C., Kim, H. 2009. Rudder gap flow control for cavitation suppression, Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Cavitation CAV2009, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

- Arndt, R.E.A., Song, C.C.S., Kjeldsen, M., Keller, A., 2000. Instability of partial cavitation: A numerical/experimental approach, proceedings of the twenty-third symposium on naval hydrodynamics, Val de Reuil, France.

- Kim, S.E., 2009. A numerical study of unsteady cavitation on a hydrofoil, in: Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Cavitation, Michigan, USA.

- Peng, X.X., Ji, B., Cao, Y., Xu, L., Zhang, G., Luo, X., Long, X., 2016. Combined experimental observation and numerical simulation of the cloud cavitation with U-type flow structures on hydrofoils, Int. J. Multiphase Flow Vol. 79. [CrossRef]

- Leroux, J., Coutier-Delgosha, O., Astolfi, J., 2005. A joint experimental and numerical study of mechanisms associated to instability of partial cavitation on two-dimensional hydrofoil, Physics of fluids. Vol. 17, pp. 052101-20. [CrossRef]

- Coutier-Delgosha, O., Deniset, F., Astolfi, J., Leroux, J., 2007. Numerical prediction of cavitating flow on a two-dimensional symmetrical hydrofoil and comparison to experiments, Journal of Fluids Eng. 129 (3), pp. 279-292. [CrossRef]

- Lu, N., Bensow, R.E., Bark, G., 2010. LES of unsteady cavitation on the delft twisted foil, J. Hydrodyn. B Vol. 22(5). [CrossRef]

- Le, Q., Franc, J.P., Michel J.M., 1993. Partial mean pressure distribution, J. Fluids Eng. Vol. 115 (2), pp. 243-248.

- Pelz, P.F., Keil, T., Ludwig, G., 2014. On the kinematics of sheet and cloud cavitation and related erosion, Advanced experimental and numerical techniques for cavitation erosion prediction, Vol. 106 of the series Fluid Mechanics and Its Applications, pp. 221-237.

- Kawanami, Y.; Kato, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Tanimura, M.; Tagaya, Y. Mechanism and control of cloud cavitation.J. Fluids Eng. 119 pp. 788 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Tanada, M.; Monden, S.; Tsujimoto, Y. Observations of oscillating cavitation on a flat plate hydrofoil. JSME Int. J. Ser. B. 45 pp. 646 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y., Nakamori, I., Ikohagi, T., 2003. Numerical analysis of unsteady vaporous cavitating flow around a hydrofoil, in: Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on Cavitation, Osaka, Japan.

- Crimi, P., 1970. Experimental study of the effects of sweep on hydrofoil loading and cavitation (Sweep angle relationship to cavitation inception on hydrofoils and to hydrofoil performance deterioration due to cavitation), J. of Hydronautics, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 3-9. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, M., 2001, Ein Beitrag zur Verminderung des erosiven Potenzials kavitierender Strömungen. PhD Thesis Technischen Universität Darmstadt.

- Choi, Y.D., Kurokawa, J., Imamura, H. 2007, Suppression of cavitation in inducers by j-grooves, J. Fluids Eng., Vol.129. [CrossRef]

- Coutier-Delgosha, O.; Devillers, J.-F.; Leriche, M.; Pichon, T. Effect of wall roughness on the dynamics of unsteady cavitation. J. Fluids Eng. 127 pp. 726-733 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H., Ishzaka, K., Watanabe, S., Furukawa, K. 2010, Cavitation surge suppression of pump inducer with axi-asymmetrical inlet plate, International Journal of Fluid Machinery and Systems, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 50-57. [CrossRef]

- Danlos, A.; Ravelet, F.; Coutier-Delgosha, O.; Bakir. F. Cavitation regime detection through proper orthogonal decomposition: Dynamics analysis of the sheet cavity on a grooved convergent–divergent nozzle. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow. 47 pp. 9 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Danlos, A.; Mehal, J.-E.; Ravelet, F.; Coutier-Delgosha, O.; Bakir. F. Study of the cavitating instability on a grooved venturi profile. J. Fluids Eng. 136 pp. 101302 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Mäkiharju, S. A., Ganesh, H., Ceccio S.L., 2017. The dynamics of partial cavity formation, shedding and the influence of dissolved and injected non-condensable gas, J. Fluid Mech. Vol. 829, pp. 420-458. [CrossRef]

- Kamikura, Y., Kobayashi, H., Kawasaki, S., Iga, Y. 2018, Three dimensional numerical analysis of inducer about suppression of cavitation instabilities by asymmetric slits on blades, IAHR Symposium, Kyoto, Japan.

- Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O.; Javadi, K. Investigation of the effect of cavitation passive control on the dynamics of unsteady cloud cavitation. Applied Mathematical Modelling. 64 pp. 333-356 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O. Investigation of cloud cavitation passive control method for hydrofoils using Cavitating-bubble Generators (CGs). International Cavitation Symposium (CAV2018), Baltimore, MD, USA. (2018).

- Kadivar, E.; Timoshevskiy, M.V.; Nichik, M.Y.; el Moctar, O.; Schellin, T.E.; Pervunin, K.S. Control of unsteady partial cavitation and cloud cavitation in marine engineering and hydraulic systems. Phys. Fluids. 32 pp. 052108 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.; Reclari, M.; Sano, T.; Iino, M.; Farhat, M. Suppressing tip vortex cavitation by winglets. Exp. Fluids. 60 pp. 159 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, E. Experimental and Numerical Investigations of Cavitation Control Using Cavitating-bubble Generators, PhD Thesis, University of Duisburg-Essen, Duisburg, Germany (2020).

- Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O.; Javadi, K. Stabilization of cloud cavitation instabilities using cylindrical cavitating-bubble generators (CCGs). International Journal of Multiphase Flow. 115 pp. 108-125 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, E.; Timoshevskiy, M.V.; Pervunin, K.S.; el Moctar, O. Cavitation control using cylindrical cavitating-bubble generators (CCGs): Experiments on a benchmark CAV2003 hydrofoil. Int. J. Multiphase Flow. 125 pp. 103186 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.-G.; Zhang, L.-X.; Shao, X.-M.; Deng, J. Numerical study on the control mechanism of cloud cavitation by obstacles. J. Hydrodyn., Ser. B. 22 pp. 792 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Javadi, K.; Mortezazadeh Dorostkar, M.; Katal. A. Cavitation passive control on immersed bodies. Journal of Marine Science and Application. 16 pp. 33–41 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, E.; Javadi, K. Effect of Cavitating-bubble Generators on the Dynamics of Unsteady Cloud Cavitation, The 19th Marine Industries Conference, Kish, Iran (2017).

- Zhao, W. G.; Wang, G. Research on passive control of cloud cavitation based on a bionic fin-fin structure. Eng. Comput. 37 pp. 863 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yang, Q.; Yang, W.; Chang, H.; Wang, H. Bionic leading-edge protuberances and hydrofoil cavitation. Phys. Fluids. 33 pp. 093317 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Tao, J.; Yin, D.; Zhu, Z. Numerical study on cavitation over flat hydrofoils with arc obstacles. Phys. Fluids. 33 pp. 085101 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Z. Cavitation flow and broadband noise source characteristics of NACA66 hydrofoil with a V groove on the suction surface. Ocean Engineering. 266 pp. 112889 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O.; Schellin, T.E. Experimental investigation of partial and cloud cavitation control on a hydrofoil using bio-inspired riblets. Physics of Fluids. 36 pp. 053338 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, D.; Xiao, T.; Chang, H.; Fu, X.; Wang. H. Control mechanisms of different bionic structures for hydrofoil cavitation, Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 102 pp. 106745 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Usta, O.; Öksüz, S.; Celik. F. Effect of leading-edge tubercles and surface corrugations on the performance and cavitation characteristics of twisted hydrofoils. Ocean Engineering. 335 pp. 121663 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Velayati, V.; Javadi, K.; el Moctar, O. Exploring the influence of surface microstructures on cloud cavitation control: A numerical investigation. Ocean Engineering. 188 pp. 105206 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Harish, R. Effect of unsteady cavitation on hydrodynamic performance of NACA 4412 Hydrofoil with novel triangular slot. Heliyon. 11 pp. e42266 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.; Larrarte, F.; Fruman, D. Investigation of unsteady sheet cavitation and cloud cavitation mechanisms. ASME. J. Fluids Eng. 121 pp. 289–296 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Enomoto, N.; Ishizaka, K.; Furukawa, A.; Kim, J.-H. Suppression of cavitation surge of a helical inducer occurring in partial flow conditions. Turbomachinery. 32 pp. 94 (2004).

- Ausoni, P.; Farhat, M.; Avellan, F. Hydrofoil roughness effects on von Karman vortex shedding. in 2nd IAHR International Meeting of the Workgroup on Cavitation and Dynamic Problems in Hydraulic Machinery and Systems (2007).

- Ausoni, P.; Zobeiri, A.; Avellan, F.; Farhat. M. The effects of a tripped turbulent boundary layer on vortex shedding from a blunt trailing edge hydrofoil. J. Fluids Eng. 134 pp. 051207 (2012). [CrossRef]

- H. Ganesh, S. Makiharju, and S. Ceccio, “Interaction of a compressible bubbly flow with an obstacle placed within a shedding partial cavity. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 656 pp. 012151 (2015).

- Onishi, K.; Matsuda, K.; Miyagawa, K. Influence of hydrophilic and hydrophobic coating on hydrofoil performance. in International Symposium on Transport Phenomena and Dynamics of Rotating Machinery (ISROMAC) (2017).

- Che, B.; Wu, D. Study on vortex generators for control of attached cavitation. in Fluids Engineering Division Summer Meeting (2017).

- Hao, J.; Zhang, M.; Huang, X. The influence of surface roughness on cloud cavitation flow around hydrofoils. Acta Mech. Sin. 34 pp. 10 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, M.; Shao, X. Inhibition of cloud cavitation on a flat hydrofoil through the placement of an obstacle. Ocean Eng. 155 pp. 1–9 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Custodio, D.; Henoch, C.; Johari, H. Cavitation on hydrofoils with leading edge protuberances. Ocean Eng. 162 pp. 196 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Petkovsek, M.; Hocevar, H.; Gregorcic, P. Cavitation Dynamics on Laser-Textured Surfaces. ASME Press, (2018).

- Kadivar, E.; Timoshevskiy, M.; Pervunin, K.; el Moctar, O. Experimental investigation of the passive control of unsteady cloud cavitation using miniature vortex generators (MVGs). IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 405 pp. 012002 (2019).

- Che, C.; Chu, N.; Cao, L.; Schmidt, S.J.; Likhachev, D.; Wu, D. Control effect of micro vortex generators on attached cavitation instability. Phys. Fluids. 31 pp. 064102 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Che, B.; Chu, N.; Schmidt, S.J.; Cao, L.; Likhachev, D.; Wu, D. Control effect of micro vortex generators on leading edge of attached cavitation. Phys. Fluids. 31 pp. 044102 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Che, B.; Cao, L.; Chu, N.; Likhachev, D.; Wu. D. Effect of obstacle position on attached cavitation control through response surface methodology. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 33 pp. 4265 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, E.; Timoshevskiy, M. V.; Pervunin, K. S.; el Moctar, O. Experimental and numerical study of the cavitation surge passive control around a semi-circular leading-edge flat plate. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 25, 1010–1023 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Qiu, N.; Zhou, W.; Che, B.; Wu, D.; Wang, L.; Zhu, H. Effects of microvortex generators on cavitation erosion by changing periodic shedding into new structures. Phys. Fluids. 32 pp. 104108 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Petkovsek, M.; Hocevar, M.; Gregorcic, P. Surface functionalization by nanosecond-laser texturing for controlling hydrodynamic cavitation dynamics. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 67 pp. 105126 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, G. Global cavitation patterns and corresponding hydrodynamics of the hydrofoil with leading edge roughness. Acta Mech. Sin. 36 pp. 1202 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-B.; Long, Y.; Ji, B. Experimental investigation of vortex generator influences on propeller cavitation and hull pressure fluctuations. J. Hydrodyn. 32 pp. 82 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Long, X,; Ji, B.; Peng, X.; Farhat, M. Suppressing tip-leakage vortex cavitation by overhanging grooves. Exp. Fluids. 61 pp. 159 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Svennberg, U.; Asnaghi, A.; Gustafsson, R.; Bensow, R. Experimental analysis of tip vortex cavitation mitigation by controlled surface roughness. J. Hydrodyn. 32 pp. 1059 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, C.; Zhang, M.; Huang, B.; Zhang, H. The influence of micro vortex generator on inception cavitation. Phys. Fluids. 33 pp. 103312 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, E.; Ochiai, T.; Iga, Y.; el Moctar, O. An experimental investigation of transient cavitation control on a hydrofoil using hemispherical vortex generators. J Hydrodyn. 33 pp. 1139–1147 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Cao, L.; Che, B.; Wu, R.; Yang, S.; Wu, D. Towards the control of blade cavitation in a waterjet pump with inlet guide vanes: Passive control by obstacles. Ocean Engineering. 231 pp. 108820 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Arab, F.M.; Augier, B.; Deniset, F.; Casari, P.; Astolfi, J.A. Effects on cavitation inception of leading and trailing edge flaps on a high-performance hydrofoil. Applied Ocean Research. 126 pp. 103285 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, E.; Lin, Y.; el Moctar, O. Experimental investigation of the effects of cavitation control on the dynamics of cavitating flows around a circular cylinder. Ocean Engineering. 286 pp. 115634 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Qiu, N.; Xu, P.; Zhu, H.; Gong, Y.; Che, B.; Zhou, W. Effect of micro vortex generators on cavitation collapse and pressure pulsation: An experimental investigation. Ocean Engineering. 288 pp. 116060 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, E.; Dawoodian, M.; Lin, Y.; el Moctar, O. Experiments on Cavitation Control around a Cylinder Using Biomimetic Riblets. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 12 pp. 293 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Nichik, M.Y.; Ilyushin, B.B.; Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O.; Pervunin. K.S. Cavitation suppression and transformation of turbulence structure in the cross flow around a circular cylinder: Surface morphology and wettability effects. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 106 pp. 106875 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O. Experimental investigation of passive cavitation control on a cylinder using proper orthogonal decomposition. Applied Ocean Research. 158 pp. 104569 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Qiu, N.; Zhu, H.; Che, B.; Zhou, W.; Bai, Y.; Wang, C. Interaction mechanism between cloud cavitation and micro vortex flows. Ocean Engineering. 297 pp. 117004 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Qiu, N.; Xu, P.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, W.; Xun, D.; Li, M.; Che, B. Cavitation morphology and erosion on hydrofoil with slits. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences. 275 pp. 109345 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, L.; Huang, B.; Wu, D. Suppression of unsteady cavitation around oscillating hydrofoils using spanwise obstacles near trailing edge. Energy. 330 pp. 136754 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O. Experimental study of cavitation control on a hydrofoil with bio-inspired riblets using proper orthogonal decomposition. Ocean Engineering. 334 pp. 121500 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O. Numerical Analysis of Cavitation Suppression on a NACA 0018 Hydrofoil Using a Surface Cavity. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 13 pp. 1517 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Qiu, N.; Xu, P.; Zhou, W.; Gong, Y.; Che, B. Cavitation erosion characteristics influenced by a microstructure at different scales. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences. 285 pp. 109842 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Çelik, F.; Usta, O.; Öksüz, S; Delikan, M.; Kara, E.; Özsayan, S.; Ünal, U.O. Experimental investigation of leading-edge tubercle and surface corrugation effects on cavitation and noise in partially cavitating twisted hydrofoils. Ocean Engineering. 324 pp. 120646 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Lin, P.; Dou, W.; Jin, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Li, X. Investigation of cavitation control mechanism around bionic hydrofoil from multi-perspective vortex identification methods. Ocean Engineering. 339 pp. 122079 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Arndt, R. E. A.; Ellis, C. R., Paul, S. Preliminary Investigation of the Use of Air Injection to Mitigate Cavitation Erosion. J. Fluids Eng.. 117 pp. 498-504 (1995).

- Reisman, G. E., Duttweiler, M. E., Brennen, C. E., 1997. Effect of air injection on the cloud cavitation of a hydrofoil, ASME Fluids Engineering Division Summer Meeting FEDSM’97.

- Zhang, Q., Hsiao, C. T., Chahine, G.L., 2009. Numerical study of vortex cavitation suppression with polymer injection, 7th International Symposium on Cavitation CAV2009, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

- Hsiao, C.-T., Zhang, Q., Wu, X., Chahine, G. L., 2010. Effects of polymer injection on vortex cavitation inception, 28th Symposium on Naval Hydrodynamics Pasadena, California.

- Chahine, G. L., Hsiao, C.-T., Wu, X., Zhang, Q., Ma, J., 2012, Vortex cavitation inception delay by local polymer injection, 29th Symposium on Naval Hydrodynamics Gothenburg, Sweden.

- Ceccio, S. L., 2010, Friction drag reduction of external flows with bubble and gas injection, Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N., Zhao, Y., Wei, H., Chen, G., 2016, Experimental study on the influence of air injection on unsteady cloud cavitating flow dynamics, Advances in Mechanical Engineering, Vol. 8, pp.1-7. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yi, Q.; Lu, S.; Wang, X. Exploration and research of the impact of hydrofoil surface water injection on cavitation suppression. In Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air. 50817 pp. V02DT46A013 (2017).

- Wang, Z., Huang, B., Zhang, M., Wang, G., Zhao, X., 2018a, Experimental and numerical investigation of ventilated cavitating flow structures with special emphasis on vortex shedding dynamics, Int. J. Multiphase Flow, Vol. 98, pp. 79. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Huang, B., Zhang, M., Wang, G., Wu, Q., Kong, D., 2018b. Effects of air injection on the characteristics of unsteady sheet/cloud cavitation shedding in the convergent-divergent channel. Int. J. Multiphase Flow, Vol. 106. [CrossRef]

- Timoshevskiy, M.V.; Zapryagaev, I.I., Pervunin, K.S.; Maltsev, L.I.; Markovich, D.M.; Hanjalic, K. Manipulating cavitation by a wall jet: Experiments on a 2D hydrofoil. International Journal of Multiphase Flow. 99 pp. 312–328 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tang, T.; Zhang, Q. D.; Wang, X. F.; An, Z. Y.; Tong, T. H.; Li, Z. J. Effect of water injection on the cavitation control:experiments on a NACA66 (MOD) hydrofoil. Acta Mechanica Sinica. 36 pp. 999–1017 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, T.; Lu, S.; Yi, Q.; Wang, X. Numerical study of the impact of water injection holes arrangement on cavitation flow control. Science Progress. 103 pp. 1–23 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wang, Z.; Zou, L.; Wang, H. Numerical investigation of positive effects of ventilated cavitation around a NACA66 hydrofoil. Ocean Engineering. 197 pp. 106831 (2020). [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, M.G.; Fontanarosa, D.; Ficarella, A. Active Control of Unsteady Cavitating Flows Over Hydrofoil. ASME. J. Fluids Eng. 142 pp. 111201 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Li, J.; Wu, M.; Xie, C.; Liu, C.; Qi, F. Study on the influence of active jet parameters on the cavitation performance of Clark-Y hydrofoil. Ocean Engineering. 261 pp. 111900 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Luo, X., Qian, Z.; Wang, X.; Yu, A. Mode vortex and turbulence in ventilated cavitation over hydrofoils. International Journal of Multiphase Flow. 157 pp. 104252 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Yin, Z.; Yu, S.; He, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Wu, D.; Mou, J.; Ren, Y. Suppression of unsteady partial cavitation by a bionic jet. International Journal of Multiphase Flow. 164 pp. 104466 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Malekshah, E.H.; Wróblewski, W.; Bochon, W.; Majkut, M. Experimental analysis on dynamic/morphological quality of cavitation induced by different air injection rates and sites. Phys. Fluids. 35 pp. 013335 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Hilo, A.K.; Go, Y-J.; Kim, G-D.; Ahn, B-K.; Park, C.; Kim, G-D.; Moon, I-S. Cheolsoo Park. Cavitating flow control and noise suppression using air injection. Phys. Fluids. 36 pp. 087146 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Duth, P.S.; Kumar, P.; Kadivar, E.; el Moctar, O. Experimental investigation of the cavitation control in a convergent–divergent nozzle using air injection. Phys. Fluids. 36 pp. 113348 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Ji, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Water Injection for Cloud Cavitation Suppression: Analysis of the Effects of Injection Parameters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 12 pp. 1277 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, W., Ji, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Active water injection combined with barchan dune vortex generators for cavitating flow noise suppression. Ocean Engineering. 312 pp. 119123 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, W., Ji, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Water injection for cloud cavitation suppression: Focusing on intervention position and jet dynamics. Ocean Engineering. 321 pp. 120437 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Hilo, A.K.; Kim, Y-J.; Hong, J-W.; Ahn, B-K. An experimental study on the effect of air injection around the leading edge of a three-dimensional hydrofoil for cavitation noise reduction. Ocean Engineering. 333 pp. 121430 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Effect of water injection on tip leakage vortex cavitation for a NACA0009 hydrofoil with medium clearance. Ocean Engineering. 320 pp. 120349 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Qu, Y.; Gao, P.; Peng, Z. Inhibition of cloud cavitation with actively controlled flexible surface driven by piezoelectric actuator. International Journal of Multiphase Flow. 192 pp. 105347 (2025). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).