1. Introduction

Mpox remains a persistent and complex public health challenge in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which continues to report the highest global burden of cases [

1,

2,

3]. The endemicity of Mpox in the DRC reflects not only viral ecology but also the vulnerabilities of fragile health systems that struggle to provide timely diagnosis, surveillance, and control. In recent years, outbreaks outside Africa have drawn global attention, yet within the DRC the disease persists as an under-addressed epidemic with profound social and economic consequences. Rural and marginalized communities bear a disproportionate burden, underscoring inequities in health access, data quality, and research attention. While zoonotic spillover from rodents and non-human primates, along with household transmission, remain the dominant pathways of spread in the DRC, emerging evidence suggests that sexual transmission may also contribute to Mpox epidemiology. Recent clusters have reported genital lesions and detection of viral DNA in semen, indicating that sexual contact could play a role alongside traditional transmission routes [

4,

5,

6]. Although not yet as well documented or dominant as in Clade II outbreaks in Europe and the Americas, this evolving evidence highlights the importance of flexible modeling frameworks that can adapt to shifting epidemiological realities.

Moreover, advances in data science and machine learning have expanded the possibilities for forecasting and early warning in infectious disease epidemiology [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Predictive intelligence, a term encompassing machine learning, geospatial modeling, and real-time surveillance analytics, offers new pathways for anticipating epidemic dynamics, identifying ecological risk zones, and informing targeted interventions. While these approaches have been piloted in other emerging infectious diseases, their application to Mpox within the DRC remains extremely limited. Weak surveillance networks, patchy laboratory infrastructure, and under-resourced data systems create barriers to both the development and operationalization of predictive tools [

12,

13]. These gaps are not merely technical but structural, reflecting broader inequities in global health research and response.

This narrative review examines the role of predictive intelligence in Mpox control, focusing specifically on the opportunities and constraints in the DRC. Our intention is not to benchmark algorithms or provide a systematic synthesis of model performance. Rather, we highlight conceptual foundations, methodological innovations, and equity considerations that are relevant to fragile and data-sparse contexts. By situating predictive approaches within the realities of the DRC health system, we aim to show how methodological advances can be adapted, rather than transplanted, to support context-sensitive epidemic preparedness. The review further emphasizes the importance of fairness, participatory engagement, and governance in shaping predictive intelligence as a tool for equitable public health action. Ultimately, our discussion frames predictive intelligence not only as a technical innovation but also as a potential lever for reducing health inequities and strengthening epidemic response capacity in one of the world’s most affected settings.

2. Foundations of Predictive Intelligence for Mpox

2.1. Principles and Scope

Predictive intelligence refers to the integration of machine learning, geospatial analysis, and surveillance data into adaptive systems designed to anticipate outbreak dynamics and support public health decision-making. In the Mpox context, this involves not only forecasting short-term incidence trends but also identifying ecological risk zones, detecting emerging transmission pathways, and integrating One Health covariates such as land use, climate variability, human mobility, and animal reservoirs [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

The scope of predictive intelligence extends beyond epidemic forecasting. Properly embedded within fragile health systems, predictive frameworks can enhance routine surveillance, inform preparedness planning, and support equity-focused interventions in marginalized populations. They can also facilitate the early detection of non-linear spillover processes, particularly in zoonotic contexts like Mpox where environmental and socio-behavioral drivers interact [

10,

19]. Importantly, predictive intelligence must balance methodological sophistication with transparency, interpretability, and alignment with local health governance structures [

20,

21,

22]. When appropriately adapted, these systems represent not just analytical tools, but potential levers for reducing inequities and strengthening epidemic preparedness in endemic settings.

2.2. Comparisons with Statistical Approaches

Classical regression and compartmental models remain valuable, particularly for estimating transmission parameters and testing epidemiological hypotheses. However, they struggle with the highly zero-inflated and sparse surveillance data typical of the DRC, where underreporting and diagnostic delays are common [

22,

23]. By contrast, machine learning approaches such as ensemble models and neural networks can capture nonlinearities, interactions, and latent risk drivers without strict parametric assumptions [

22]. Importantly, predictive intelligence should not replace statistical methods but complement them, creating hybrid pipelines that combine epidemiological interpretability with ML flexibility.

3. Opportunities for Application

3.1. Forecasting Mpox Dynamics

Spatiotemporal machine learning models provide actionable forecasts that can inform rapid response planning in fragile health systems. Approaches such as random forests, gradient boosting, and neural networks have demonstrated utility in African outbreak contexts, including Ebola, Covid-19 and malaria, where traditional surveillance is incomplete [

12,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. For the Democratic Republic of Congo, such models could generate province-level forecasts of Mpox incidence, enabling authorities to anticipate short- and medium-term spikes, pre-position medical supplies, and intensify surveillance in high-risk zones. Importantly, the value of machine learning lies not only in predictive accuracy but also in its ability to integrate diverse One Health covariates and adapt to sparse, heterogeneous data. To be operationally useful, these forecasting systems must also prioritize transparency and interpretability, ensuring they can be trusted by decision-makers in under-resourced settings.

3.2. Hybrid and Ensemble Approaches

Hybrid models, which integrate multiple algorithms into a single predictive pipeline, have gained traction in infectious disease forecasting because they combine complementary strengths. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) excel at capturing nonlinear relationships, while boosting methods such as XGBoost reduce residual errors and enhance generalizability [

8,

29]. Ensemble frameworks, including stacked or residual-corrected hybrids, have consistently demonstrated superior accuracy in forecasting epidemics such as influenza, dengue, Ebola, and COVID-19, particularly in data-limited settings where single-algorithm pipelines often underperform [

25,

30,

31].

Beyond improved accuracy, hybrid and ensemble designs enable probabilistic forecasting and uncertainty quantification, which are essential for decision-making under fragile health system constraints [

22,

32]. In the Mpox context, these approaches are especially promising given sparse surveillance data, heterogeneous reporting, and nonlinear zoonotic drivers. Our ongoing work extends this line of research by developing a residual-stacked ANN + XGBoost framework tailored to the Democratic Republic of Congo, with the goal of balancing predictive accuracy, interpretability, and operational feasibility.

3.3. Illustrative Use-Cases

Predictive outputs can directly support operational decision, making in fragile health systems. For example, spatiotemporal forecasts can anticipate diagnostic kit demand, guide targeted ring vaccination in high-incidence zones, and optimize the allocation of rapid response teams. Beyond the response to the outbreak, geospatial risk maps can highlight areas where ecological change, such as deforestation and habitat invasion of wildlife, overlaps with the risk of Mpox transmission, informing One Health interventions [

24,

33,

34]. Similar approaches have been applied in Ebola and COVID-19 contexts to anticipate healthcare surge capacity and improve supply-chain planning [

25,

31]. These examples underscore the translational potential of predictive intelligence when embedded within stronger surveillance workflows, ensuring that forecasts are actionable rather than merely descriptive.

3.4. Geospatial Risk Mapping and Prioritization

Mpox spillover in the DRC is associated with putative reservoirs such as rope squirrels (

Funisciurus spp.), dormice (

Graphiurus spp.), and Gambian pouched rats (

Cricetomys spp.), with occasional amplification by primates and domestic animals [

15,

24,

34]. Human infection occurs through bushmeat handling, contaminated materials, and close contact, while environmental drivers such as deforestation, biodiversity loss, and land-use change increase opportunities for spillover and transmission [

1,

3,

35]. For predictive modeling, these ecological and socio-behavioral factors represent critical covariates. Integrating spatial ecology, human mobility, and land-use data with machine learning can improve detection of non-linear spillover patterns and enable more effective early-warning systems [

8,

27].

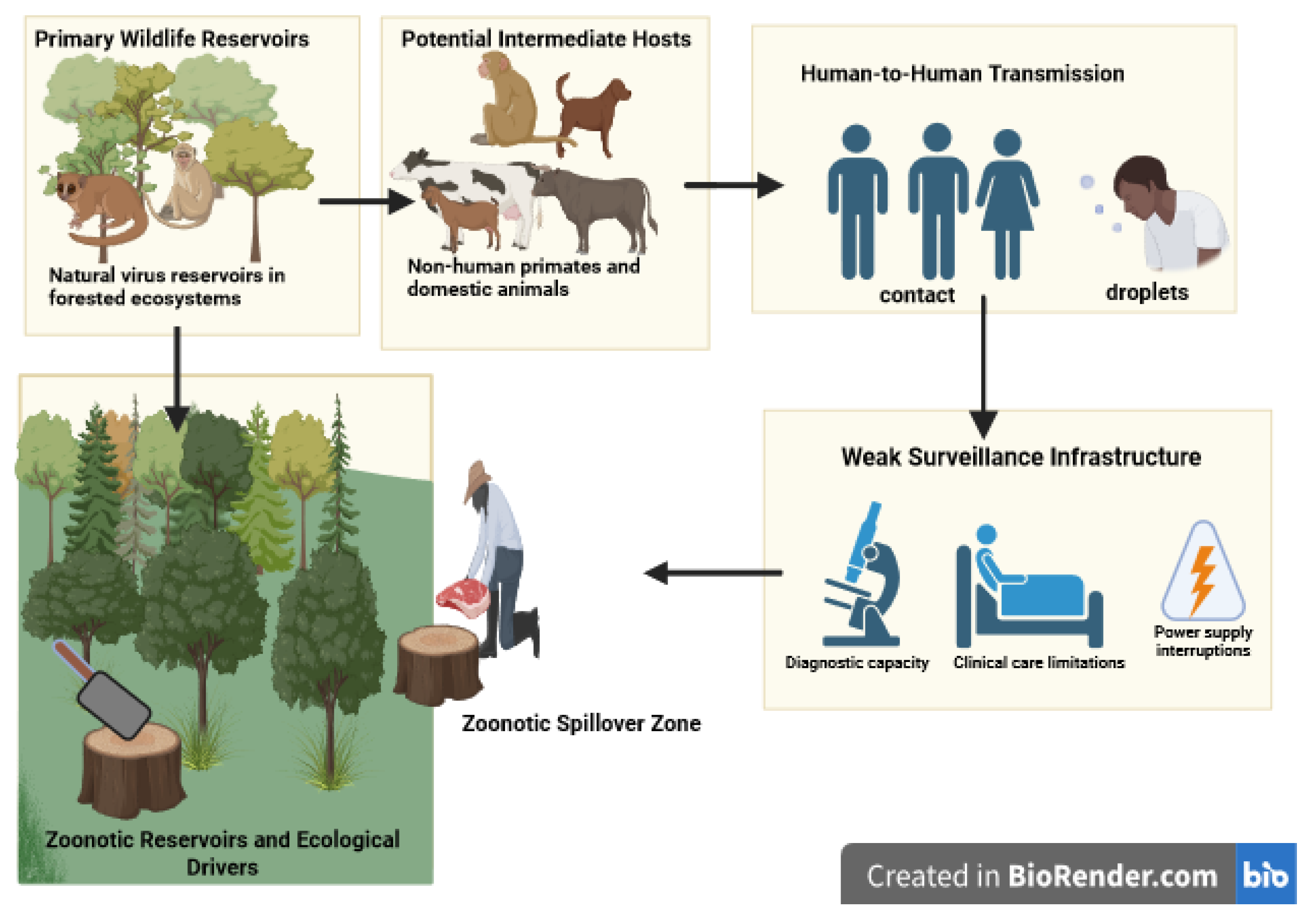

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of zoonotic spillover pathways of Clade I Mpox in the DRC. Rodents are the primary suspected reservoirs, with possible amplification by primates and domestic animals. Human cases arise through contact with animals, bushmeat, or fomites, with limited human-to-human transmission through close contact and droplets. Environmental drivers such as deforestation, bushmeat trade, and weak surveillance amplify spillover risk. These factors represent essential covariates for machine learning–based predictive models. Figure created with

https://biorender.com.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of zoonotic spillover pathways of Clade I Mpox in the DRC. Rodents are the primary suspected reservoirs, with possible amplification by primates and domestic animals. Human cases arise through contact with animals, bushmeat, or fomites, with limited human-to-human transmission through close contact and droplets. Environmental drivers such as deforestation, bushmeat trade, and weak surveillance amplify spillover risk. These factors represent essential covariates for machine learning–based predictive models. Figure created with

https://biorender.com.

4. Equity, Ethics, and Context

4.1. Bias, Representation, and Fairness

Health data in the DRC are unevenly distributed, with surveillance often stronger in urban and better-resourced provinces compared to rural and marginalized regions. This imbalance risks embedding algorithmic bias, where models disproportionately capture urban dynamics while neglecting rural spillover pathways. Such bias could exacerbate existing inequities in outbreak response. Fairness-aware machine learning methods, subgroup validation, and stratified evaluation are essential to ensure that predictions remain representative and equitable across diverse communities [

36,

37].

4.2. Participatory Approaches

Contextual adaptation of predictive systems requires the active involvement of local researchers, health workers, and communities. Participatory approaches not only build trust and legitimacy but also reveal context-specific drivers of transmission, such as cultural practices around bushmeat or mobility patterns, that external models often miss [

38,

39]. Co-designing models with local stakeholders also supports long-term sustainability by fostering co-ownership and reducing reliance on external expertise.

4.3. Governance and Accountability

Predictive intelligence must be governed with transparency, accountability, and ethical safeguards. Without such measures, models risk reinforcing donor priorities or political agendas at the expense of local needs. Open-source workflows, clear documentation, and community oversight can mitigate these risks and ensure that predictive systems align with public health priorities [

23,

40]. Embedding independent governance mechanisms is particularly important in fragile health systems where trust is limited.

5. Pathways for Operationalization in the DRC

5.1. Operational Barriers in the DRC

Weak infrastructure, limited diagnostic capacity, and fragmented health information systems constrain the integration of predictive modeling into Mpox control. Most published studies remain proof-of-concept with limited downstream translation into decision-support tools [

41,

42]. Bridging this gap requires investments in both technical innovation and system-level strengthening, including surveillance infrastructure and routine data quality improvements [

43].

5.2. Bridging Evidence and Decision-Making

Effective operationalization requires harmonizing surveillance and modeling workflows, ensuring timely data access, and strengthening feedback loops between data producers (e.g., surveillance teams, laboratories) and data users (e.g., public health officials, community leaders). Investments in local analytic capacity, through training, regional data hubs, and mentorship, are critical for reducing dependence on external partners and fostering sustainable adoption [

7,

44].

6. Future Directions and Research Agenda

Future priorities for Mpox predictive intelligence in the DRC can be framed along three interconnected axes: methodological refinement, data integration, and policy embedding. On the methodological front, advancing hybrid and ensemble pipelines that combine machine learning with Bayesian inference will be essential for managing sparse surveillance data. Explicit strategies must address zero-inflation, uncertainty quantification, and small-sample regimes, which remain persistent challenges in outbreak prediction [

30,

31]. Importantly, approaches that balance interpretability and predictive powe, such as probabilistic machine learning, are particularly valuable in fragile health systems where decision-makers require transparent, reproducible, and actionable outputs.

Data-related advances are equally pressing. Integrating

One Health covariates, including ecological, climatic, and socio-behavioral determinants, will strengthen predictive fidelity by capturing upstream drivers of Mpox emergence. Genomic surveillance is urgently needed to trace viral evolution, monitor high-risk lineages, and better understand emerging modes of transmission, including possible sexual transmission that has been suggested in recent outbreaks [

34,

45]. Linking these data streams with mobility, demographic, and health system data can substantially enhance both national and regional forecasting capacity.

Finally, embedding predictive intelligence within epidemic response frameworks requires robust governance structures that ensure equity, transparency, and sustainability. Predictive tools must be co-developed with local institutions, researchers, and health authorities to prevent donor-driven priorities from overshadowing local needs [

23,

36]. Strengthening analytic capacity within the DRC through training, mentorship, and regional data hubs will be critical to sustaining predictive systems and ensuring their long-term operational value. Bridging the gap between proof-of-concept models and real-world decision-support systems will hinge on this alignment between methodological rigor, diverse data integration, and participatory governance.

7. Conclusions

Predictive intelligence offers a transformative pathway for Mpox preparedness in the DRC. If effectively operationalized, predictive models can enable earlier detection, guide more precise interventions, and reinforce One Health responses that address the human, animal, and environmental dimensions of transmission. By explicitly incorporating genomic, behavioral, and contextual data, these models can also clarify the role of emerging risk factors, including possible sexual transmission, in sustaining outbreaks.

However, realizing this potential requires overcoming persistent barriers of data scarcity, weak health infrastructure, and inequitable representation in surveillance systems. A forward-looking research and policy agenda must therefore emphasize methodological innovation, cross-sectoral data integration, and inclusive governance. When designed with fairness, transparency, and local participation, predictive intelligence can serve not only as a scientific innovation but also as an ethical imperative for epidemic control. By bridging innovation with equity, predictive systems can transition from experimental research tools to actionable instruments, shaping resilient epidemic preparedness in the DRC and informing broader global responses [

7,

46].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L.J.U. and A.O.; Methodology, C.L.J.U. and W.A.W.; Investigation, C.L.J.U.,W.A.W., A.O. and F.A.H.; Writing:original draft preparation, C.L.J.U.; Writing:review and editing, W.A.W. A.O, and F.A.H.; Supervision, W.A.W.; Project administration, C.L.J.U. and F.A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) through the Mpox and Other Zoonotic Threats Team Grant (FRN: 187246).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing, or decision to publish.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| DRC |

Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization |

| LMICs |

Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| CART |

Classification and Regression Trees |

| XGBoost |

Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| ANN |

Artificial Neural Network |

| GIS |

Geographic Information System |

| SPDE |

Stochastic Partial Differential Equation |

| ZIP |

Zero-Inflated Poisson |

| ZINB |

Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial |

| PIT |

Probability Integral Transform |

| OCS |

Ontario Cohort Study |

References

- Bunge, E.M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; Lienert, F.; Weidenthaler, H.; Baer, L.R.; Steffen, R. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2022, 16, e0010141. [CrossRef]

- Djuicy, D.D.; Bilounga, C.N.; Esso, L.; Mouiche, M.M.M.; Yonga, M.G.W.; Essima, G.D.; Nguidjol, I.M.E.; Anya, P.J.A.; Dibongue, E.B.N.; Etoundi, A.G.M.; et al. Evaluation of the mpox surveillance system in Cameroon from 2018 to 2022: a laboratory cross-sectional study. BMC Infectious Diseases 2024, 24, 949. [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, C.L.J.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Wu, J.; Kong, J.D.; Asgary, A.; Orbinski, J.; Woldegerima, W.A. Risk factors associated with human Mpox infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health 2025, 10. [CrossRef]

- Raccagni, A.R.; Castagna, A.; Nozza, S. Detection of Mpox virus in seminal fluids: implications for sexual transmission. New Microbiol 2024, 46, 317–321.

- (WHO), W.H.O. Democratic Republic of the Congo reports first cluster of sexually transmitted Clade I Mpox. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON493, 2023. Accessed: 2025-08-16.

- Yinda, C.K.; Koukouikila-Koussounda, F.; Mayengue, P.I.; Elenga, R.G.; Greene, B.; Ochwoto, M.; Indolo, G.D.; Mavoungou, Y.V.T.; Boussam, D.A.E.; Ampiri, B.R.V.; et al. Genetic sequencing analysis of monkeypox virus clade I in Republic of the Congo: a cross-sectional, descriptive study. The Lancet 2024, 404, 1815–1822. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Q.; Chen, J.J.; Liu, M.C.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Wang, T.; Che, T.L.; Li, T.T.; Liu, Y.N.; Teng, A.Y.; Wu, B.Z.; et al. Mapping global zoonotic niche and interregional transmission risk of monkeypox: a retrospective observational study. Globalization and Health 2023, 19, 58. [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, H.; Daniyal, M.; Qureshi, M.; Tawiah, K.; Ansah, R.K.; Afriyie, J.K. A hybrid forecasting technique for infection and death from the mpox virus. Digital Health 2023, 9, 20552076231204748. [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, C.L.J.; Asgary, A.; Wu, J.; Kong, J.D.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Orbinski, J.; Woldegerima, W.A. Geographical distribution and the impact of socio-environmental indicators on incidence of Mpox in Ontario, Canada. PloS one 2025, 20, e0306681. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.Z.; Senthil, R.; Ramalingam, V.; Gopal, R. Predicting infectious disease outbreaks with machine learning and epidemiological data. Journal of Advanced Zoology 2023, 44, 110–121. [CrossRef]

- Towfek, S.; Elkanzi, M. A review on the role of machine learning in predicting the spread of infectious diseases. Metaheuristic Optimiz. Rev 2024, 2, 14–27. [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.T.; Greer, A.; Kini, B.; Abdi, H.; Rajeh, K.; Cortier, H.; Boboeva, M. Integrating sexual and reproductive health into health system strengthening in humanitarian settings: a planning workshop toolkit to transition from minimum to comprehensive services in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Bangladesh, and Yemen. Conflict and health 2020, 14, 81. [CrossRef]

- Ogwu, M.C.; Izah, S.C. Technologies for Predictive Modeling of Tropical Diseases. In Technological Innovations for Managing Tropical Diseases; Springer, 2025; pp. 109–130.

- Thomassen, H.A.; Fuller, T.; Asefi-Najafabady, S.; Shiplacoff, J.A.; Mulembakani, P.M.; Blumberg, S.; Johnston, S.C.; Kisalu, N.K.; Kinkela, T.L.; Fair, J.N.; et al. Pathogen-host associations and predicted range shifts of human monkeypox in response to climate change in central Africa. PloS one 2013, 8, e66071. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, T.; Thomassen, H.A.; Mulembakani, P.M.; Johnston, S.C.; Lloyd-Smith, J.O.; Kisalu, N.K.; Lutete, T.K.; Blumberg, S.; Fair, J.N.; Wolfe, N.D.; et al. Using remote sensing to map the risk of human monkeypox virus in the Congo Basin. EcoHealth 2011, 8, 14–25. [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.E.; Patel, N.G.; Levy, M.A.; Storeygard, A.; Balk, D.; Gittleman, J.L.; Daszak, P. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 2008, 451, 990–993. [CrossRef]

- Plowright, R.K.; Parrish, C.R.; McCallum, H.; Hudson, P.J.; Ko, A.I.; Graham, A.L.; Lloyd-Smith, J.O. Pathways to zoonotic spillover. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2017, 15, 502–510. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Chong, Z.; Xu, E.; Na, C.; Liu, K.; Chai, L.; Xia, P.; Yang, K.; Zhu, G.; Zhao, J.; et al. Environmental, socioeconomic, and sociocultural drivers of monkeypox transmission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: a One Health perspective. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2025, 14, 7. [CrossRef]

- Scarpino, S.V.; Petri, G. On the predictability of infectious disease outbreaks. Nature communications 2019, 10, 898. [CrossRef]

- Metta, C.; Beretta, A.; Pellungrini, R.; Rinzivillo, S.; Giannotti, F. Towards transparent healthcare: advancing local explanation methods in explainable artificial intelligence. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 369. [CrossRef]

- Peggy, O.O.; et al. Advanced machine learning-driven business analytics for real-time health risk stratification and cost prediction models. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 2025, 26, 150–167. [CrossRef]

- Woldegerima, W.A.; Ugwu, C.L.J. Bayesian Hierarchical Modeling of Mpox in the African Region (2022–2024): Addressing Zero-Inflation and Spatial Autocorrelation. Infectious Disease Modelling 2025. [CrossRef]

- Alami, H.; Rivard, L.; Lehoux, P.; Hoffman, S.J.; Cadeddu, S.B.M.; Savoldelli, M.; Samri, M.A.; Ag Ahmed, M.A.; Fleet, R.; Fortin, J.P. Artificial intelligence in health care: laying the foundation for responsible, sustainable, and inclusive innovation in low-and middle-income countries. Globalization and Health 2020, 16, 52. [CrossRef]

- Pigott, D.M.; Golding, N.; Mylne, A.; Huang, Z.; Henry, A.J.; Weiss, D.J.; Brady, O.J.; Kraemer, M.U.; Smith, D.L.; Moyes, C.L.; et al. Mapping the zoonotic niche of Ebola virus disease in Africa. elife 2014, 3, e04395. [CrossRef]

- Sarumi, O.A. Machine learning-based big data analytics framework for ebola outbreak surveillance. In Proceedings of the International conference on intelligent systems design and applications. Springer, 2020, pp. 580–589.

- Brosius, I.; Vakaniaki, E.H.; Mukari, G.; Munganga, P.; Tshomba, J.C.; De Vos, E.; Bangwen, E.; Mujula, Y.; Tsoumanis, A.; Van Dijck, C.; et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of mpox during the clade Ib outbreak in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet 2025, 405, 547–559. [CrossRef]

- Folasole, A. Data analytics and predictive modelling approaches for identifying emerging zoonotic infectious diseases: surveillance techniques, prediction accuracy, and public health implications. Int J Eng Technol Res Manag 2023, 7, 292.

- Nabi, K.N. Forecasting COVID-19 pandemic: A data-driven analysis. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2020, 139, 110046. [CrossRef]

- Zeroual, A.; Harrou, F.; Dairi, A.; Sun, Y. Deep learning methods for forecasting COVID-19 time-Series data: A Comparative study. Chaos, solitons & fractals 2020, 140, 110121. [CrossRef]

- Reich, N.G.; McGowan, C.J.; Yamana, T.K.; Tushar, A.; Ray, E.L.; Osthus, D.; Kandula, S.; Brooks, L.C.; Crawford-Crudell, W.; Gibson, G.C.; et al. Accuracy of real-time multi-model ensemble forecasts for seasonal influenza in the US. PLoS computational biology 2019, 15, e1007486. [CrossRef]

- Sherratt, K.; Gruson, H.; Johnson, H.; Niehus, R.; Prasse, B.; Sandmann, F.; Deuschel, J.; Wolffram, D.; Abbott, S.; Ullrich, A.; et al. Predictive performance of multi-model ensemble forecasts of COVID-19 across European nations. Elife 2023, 12, e81916. [CrossRef]

- Ray, E.L.; Reich, N.G. Prediction of infectious disease epidemics via weighted density ensembles. PLoS computational biology 2018, 14, e1005910.

- Curaudeau, M.; Besombes, C.; Nakouné, E.; Fontanet, A.; Gessain, A.; Hassanin, A. Identifying the most probable mammal reservoir hosts for monkeypox virus based on ecological niche comparisons. Viruses 2023, 15, 727. [CrossRef]

- Alakunle, E.F.; Okeke, M.I. Monkeypox virus: a neglected zoonotic pathogen spreads globally. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2022, 20, 507–508. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Jung, J.; Peck, K.R. Monkeypox: the resurgence of forgotten things. Epidemiology and health 2022, 44, e2022082. [CrossRef]

- Rajkomar, A.; Hardt, M.; Howell, M.D.; Corrado, G.; Chin, M.H. Ensuring fairness in machine learning to advance health equity. Annals of internal medicine 2018, 169, 866–872. [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.Y.; Pierson, E.; Rose, S.; Joshi, S.; Ferryman, K.; Ghassemi, M. Ethical machine learning in healthcare. Annual review of biomedical data science 2021, 4, 123–144. [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.Y.; Hickie, I.B.; Occhipinti, J.A.; Song, Y.J.C.; Skinner, A.; Camacho, S.; Lawson, K.; Hilber, A.M.; Freebairn, L. Presenting a comprehensive multi-scale evaluation framework for participatory modelling programs: A scoping review. PloS one 2022, 17, e0266125. [CrossRef]

- Abimbola, S.; Pai, M. The community as a unit of care in global health. BMJ Global Health 2021, 6, e004872.

- Khosravi, M.; Zare, Z.; Mojtabaeian, S.M.; Izadi, R. Ethical challenges of using artificial intelligence in healthcare delivery: a thematic analysis of a systematic review of reviews. Journal of Public Health 2024, pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, I.P. Critical analysis of infectious disease surveillance and response system in Nigeria. Discover Public Health 2025, 22, 272. [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M.E. Emergency preparedness and public health systems: lessons for developing countries. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2008, 34, 529–534. [CrossRef]

- Prakash Narain, J.; Sodani, P.; Kant, L. COVID-19 pandemic: lessons for the health systems. Journal of Health Management 2021, 23, 74–84. [CrossRef]

- Beyene, J.; Harrar, S.W.; Altaye, M.; Astatkie, T.; Awoke, T.; Shkedy, Z.; Mersha, T.B. A roadmap for building data science capacity for health discovery and innovation in Africa. Frontiers in public health 2021, 9, 710961. [CrossRef]

- Araf, Y.; Nipa, J.F.; Naher, S.; Maliha, S.T.; Rahman, H.; Arafat, K.I.; Munif, M.R.; Uddin, M.J.; Jeba, N.; Saha, S.; et al. Insights into the transmission, host range, genomics, vaccination, and current epidemiology of the monkeypox virus. Veterinary Medicine International 2024, 2024, 8839830. [CrossRef]

- Essack, Z.; Ndebele, P.; Matisonn, H.; de Vries, J.; Moodley, K.; Rennie, S.; Ali, J.; Kass, N.; IJsselmuiden, C.; Mkhize, N.; et al. Health Research Ethics in Southern Africa: Building Capacity and Cultivating Excellence. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 2025, p. 15562646251347549. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).