Submitted:

16 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. PPP Infrastructures

2.2. Climate Risks

2.3. Strategies on Managing Climate Risks

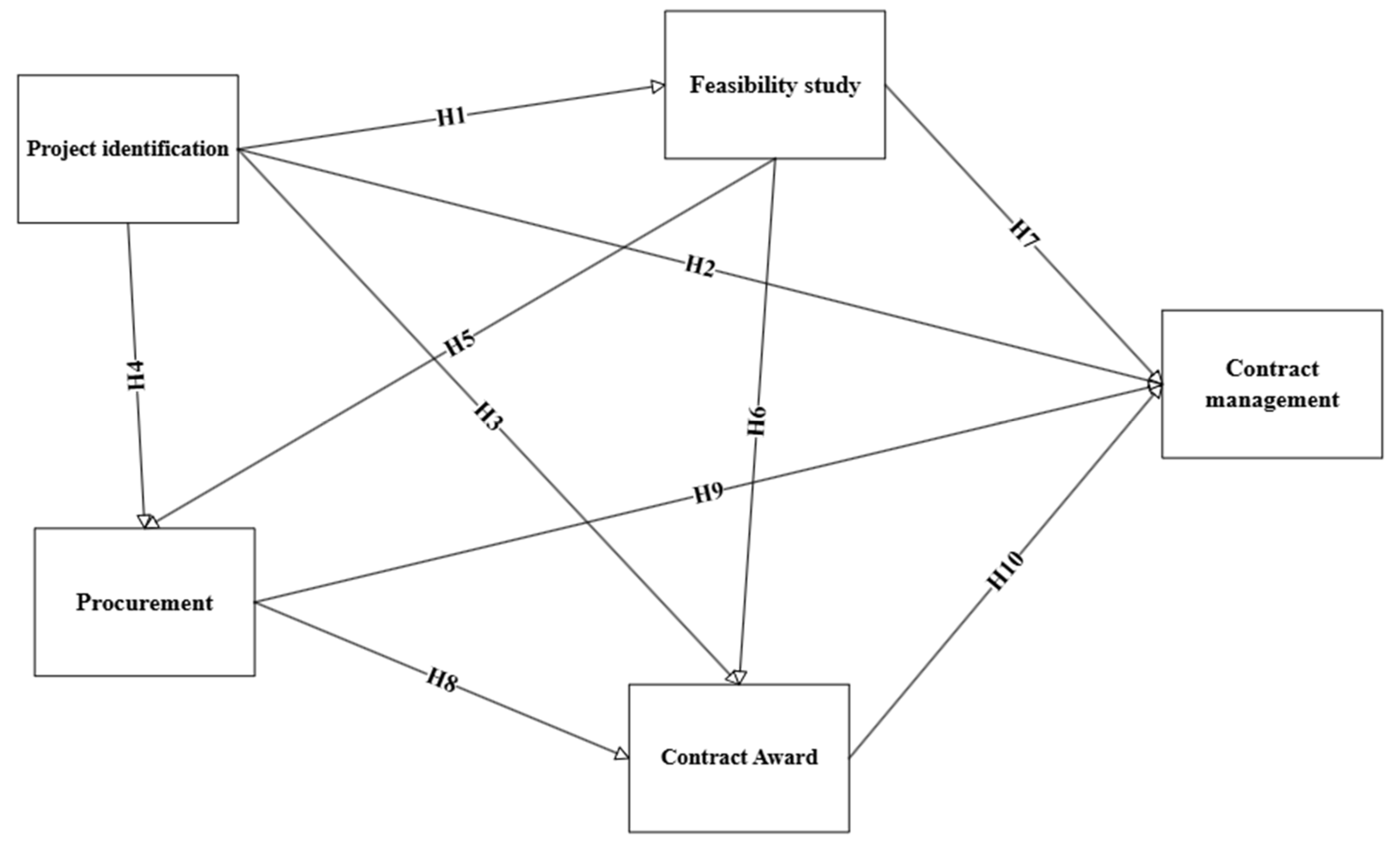

3. Hypothesis Development

4. Methodology

4.1. Questionnaire

4.2. Respondents and Survey

4.3. Analysing the Data

5. Results and Discussions

5.1. Profile of Respondents

5.2. Analysis Using the PLS-SEM

5.2.1. The Measurement Model

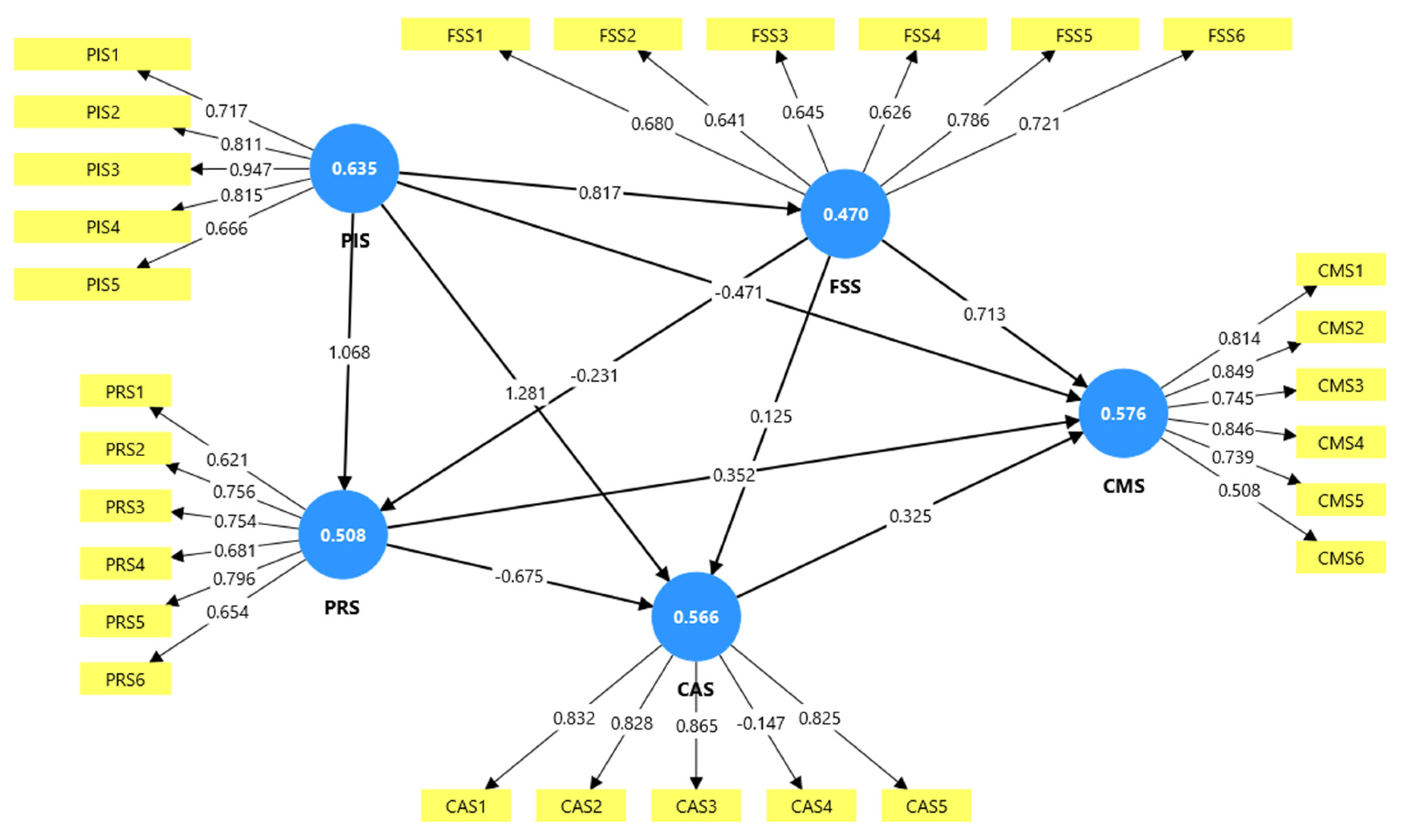

| Constructs | Indicators | Factor loadings | CA | CR | AVE | VIF |

| PIS | 0.851 | 0.857 | 0.635 | |||

| PIS1 | 0.717 | 1.467 | ||||

| PIS2 | 0.811 | 1.185 | ||||

| PIS3 | 0.946 | 1.304 | ||||

| PIS4 | 0.814 | 1.411 | ||||

| PIS5 | 0.667 | 1.327 | ||||

| FSS | 0.778 | 0.802 | 0.507 | |||

| FSS1 | 0.681 | 1.890 | ||||

| FSS2 | 0.641 | 1.375 | ||||

| FSS3 | 0.646 | 1.436 | ||||

| FSS4 | 0.626 | 1.499 | ||||

| FSS5 | 0.786 | 1.772 | ||||

| FSS6 | 0.721 | 1.790 | ||||

| PRS | 0.805 | 0.816 | 0.518 | |||

| PRS1 | 0.620 | 1.490 | ||||

| PRS2 | 0.756 | 2.161 | ||||

| PRS3 | 0.754 | 1.897 | ||||

| PRS4 | 0.681 | 2.208 | ||||

| PRS5 | 0.796 | 2.057 | ||||

| PRS6 | 0.654 | 1.630 | ||||

| CAS | 0.859 | 0.860 | 0.702 | |||

| CAS1 | 0.835 | 2.014 | ||||

| CAS2 | 0.826 | 1.937 | ||||

| CAS3 | 0.865 | 2.256 | ||||

| CAS5 | 0.825 | 1.971 | ||||

| CMS | 0.845 | 0.852 | 0.576 | |||

| CMS1 | 0.814 | 2.565 | ||||

| CMS2 | 0.848 | 1.944 | ||||

| CMS3 | 0.744 | 1.782 | ||||

| CMS4 | 0.846 | 2.401 | ||||

| CMS5 | 0.739 | 1.645 | ||||

| CMS6 | 0.509 | 1.193 |

| CAS | CMS | FSS | PIS | PRS | |

| CAS1 | 0.435 | 0.552 | 0.620 | 0.634 | 0.393 |

| CAS2 | 0.526 | 0.464 | 0.540 | 0.672 | 0.414 |

| CAS3 | 0.665 | 0.619 | 0.644 | 0.684 | 0.477 |

| CAS5 | 0.325 | 0.586 | 0.674 | 0.629 | 0.479 |

| CMS1 | 0.480 | 0.214 | 0.611 | 0.468 | 0.428 |

| CMS2 | 0.429 | 0.648 | 0.557 | 0.435 | 0.447 |

| CMS3 | 0.463 | 0.544 | 0.530 | 0.415 | 0.377 |

| CMS4 | 0.501 | 0.246 | 0.630 | 0.536 | 0.439 |

| CMS5 | 0.106 | 0.439 | 0.670 | 0.600 | 0.386 |

| CMS6 | 0.389 | 0.509 | 0.580 | 0.614 | 0.511 |

| FSS1 | 0.416 | 0.301 | 0.681 | 0.478 | 0.323 |

| FSS2 | 0.444 | 0.328 | 0.641 | 0.658 | 0.535 |

| FSS3 | 0.350 | 0.427 | 0.646 | 0.501 | 0.362 |

| FSS4 | 0.413 | 0.567 | 0.626 | 0.488 | 0.486 |

| FSS5 | 0.173 | 0.476 | 0.286 | 0.661 | 0.544 |

| FSS6 | 0.568 | 0.403 | 0.321 | 0.532 | 0.319 |

| PIS1 | 0.585 | 0.477 | 0.178 | 0.317 | 0.512 |

| PIS2 | 0.444 | 0.450 | 0.509 | 0.411 | 0.455 |

| PIS3 | 0.746 | 0.604 | 0.638 | 0.146 | 0.111 |

| PIS4 | 0.851 | 0.592 | 0.589 | 0.214 | 0.526 |

| PIS5 | 0.445 | 0.556 | 0.632 | 0.667 | 0.494 |

| PRS1 | 0.263 | 0.255 | 0.342 | 0.625 | 0.620 |

| PRS2 | 0.444 | 0.428 | 0.441 | 0.303 | 0.556 |

| PRS3 | 0.399 | 0.438 | 0.485 | 0.694 | 0.254 |

| PRS4 | 0.463 | 0.457 | 0.499 | 0.544 | 0.581 |

| PRS5 | 0.445 | 0.491 | 0.552 | 0.661 | 0.296 |

| PRS6 | 0.162 | 0.321 | 0.405 | 0.503 | 0.654 |

| Fornell-Larcker | |||||

| CAS | CMS | FSS | PIS | PRS | |

| CAS | 0.838 | ||||

| CMS | 0.664 | 0.759 | |||

| FSS | 0.74 | 0.793 | 0.686 | ||

| PIS | 0.781 | 0.678 | 0.817 | 0.797 | |

| PRS | 0.526 | 0.568 | 0.641 | 0.879 | 0.713 |

| Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) | |||||

| CAS | CMS | FSS | PIS | PRS | |

| CAS | |||||

| CMS | 0.772 | ||||

| FSS | 0.765 | 0.619 | |||

| PIS | 0.808 | 0.803 | 0.792 | ||

| PRS | 0.613 | 0.687 | 0.783 | 0.762 | |

5.2.2. The Structural Model Assessment

6. Discussions

7. Conclusions, Implications and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Matteis, F.; Borgonovi, E.; Notaristefano, G.; Striani, F. The contribution of public-private partnership (PPP) to sustainability: governance and managerial implications from a literature review. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 2025, 25, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atamanov, A.; Lakner, C.; Mahler, D.G.; Tetteh Baah, S.K.; Yang, J. The effect of new PPP estimates on global poverty: A first look; World Bank, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chileshe, N.; Njau, C.W.; Kibichii, B.K.; Macharia, L.N.; Kavishe, N. Critical success factors for Public-Private Partnership (PPP) infrastructure and housing projects in Kenya. International Journal of Construction Management 2022, 22, 1606–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Agyekum, A.K.; Amoakwa, A.B.; Babon-Ayeng, P.; Pariafsai, F. Toward the attainment of climate-smart PPP infrastructure projects: A critical review and recommendations. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2024, 26, 19195–19229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R. Review of public–private partnerships across building sectors in nine European countries: Key adaptations for PPP in housing. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2023, 30, 2904–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Z. Government-enterprise green collaborative governance and urban carbon emission reduction: Empirical evidence from green PPP programs. Environmental Research 2024, 257, 119335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.; Kamran, M.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Zhai, H.; Demirkesen, S. Evaluating the impact of contracting and procurement methods on energy and carbon emissions reduction in the public construction sector. In ASCE Inspire 2023; 2023; pp. 886–894. [Google Scholar]

- Che, S.; Wen, L.; Wang, J. Global insights on the impact of digital infrastructure on carbon emissions: a multidimensional analysis. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 368, 122144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Hashmi, S.H.; Habib, Y.; Kirikkaleli, D. The asymmetric impact of public–private partnership investment in energy on CO2 emissions in Pakistan. Energy & environment 2024, 35, 2131–2150. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri, A.; Gumiere, S.; Bonakdari, H. Firestorm in California: The new reality for wildland-urban interface regions. Urban Climate 2025, 62, 102528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Nair, D.J.; Waller, S.T. Implementing equitable wildfire response plans. Science 2025, 388, 158–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Chen, N.; Tang, R.; Yang, Z.; Jiao, M.; Wen, T.; Wang, Y.; Jin, J. Slope failure mechanism of the “5· 1” Meida Highway collapse in Guangdong, China: interaction between multi-source water and weathered granite soil. Landslides 2025, 22, 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkmann, J.; Truedinger, A.; Schuettrumpf, H. The Impact of Science: Uptake of Scientific Recommendations After Extreme Events—Case Study Floods in 2021 in Germany. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2025, 18, e70100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, D.C.; Crespo, N.M.; da Silva, D.V.; Harada, L.M.; de Godoy, R.M.P.; Domingues, L.M.; Luiz, R.; Bortolozo, C.A.; Metodiev, D.; de Andrade, M.R.M. Extreme rainfall and landslides as a response to human-induced climate change: a case study at Baixada Santista, Brazil, 2020. Natural Hazards 2024, 120, 10835–10860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagbemi, F.; Fajingbesi, A.; Bello, K.M. Infrastructure Impact of Climate Change in Sub-Saharan Africa: Is the Decarbonizing Strategy the Cinderella of Climate Action? Journal of Critical Infrastructure Policy 2025, 6, e12042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Zhao, C.; Iqbal, N.; Gülmez, Ö.; Işik, H.; Kirikkaleli, D. Does energy productivity and public-private investment in energy achieve carbon neutrality target of China? Journal of Environmental management 2021, 298, 113464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giesekam, J.; Tingley, D.D.; Cotton, I. Aligning carbon targets for construction with (inter) national climate change mitigation commitments. Energy Build. 2018, 165, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, R. Decarbonising construction: Six things the industry could do. Construction Research and Innovation 2019, 10, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xue, L.; Khan, Z. What abates carbon emissions in China: Examining the impact of renewable energy and green investment. Sustainable Development 2021, 29, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Chan, M.; Bai, Y. Joint Optimization of Critical Concession Parameters for Sustainable PPP Contracts. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2025, 151, 04025051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Anwar, A.; Irmak, E.; Pelit, I. Asymmetric linkages between public-private partnership, environmental innovation, and transport emissions. Ekon. Istraz. 2022, 35, 6519–6540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Liu, Y.; Hope, A.; Wang, J. Review of studies on the public–private partnerships (PPP) for infrastructure projects. International journal of project management 2018, 36, 773–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Shen, Q.; Cheng, E.W. A review of studies on public–private partnership projects in the construction industry. International journal of project management 2010, 28, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.X.; Wang, S.; Fang, D. A life-cycle risk management framework for PPP infrastructure projects. Journal of financial management of property and construction 2008, 13, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Dzagli, J.R.A.D.; Eluerkeh, K.; Bonsu, F.B.; Opoku-Brafi, S.; Gyimah, S.; Asuming, N.A.S.; Atibila, D.W.; Kukah, A.S. A systematic review of artificial intelligence in managing climate risks of PPP infrastructure projects. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, D.d.C.e.S.; Cruz, C.O.; Rodrigues, F.; Silva, P. PPP development and governance in Latin America: analysis of Brazilian state PPP units. Journal of Infrastructure Systems 2020, 26, 05020003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillett, N.P.; Kirchmeier-Young, M.; Ribes, A.; Shiogama, H.; Hegerl, G.C.; Knutti, R.; Gastineau, G.; John, J.G.; Li, L.; Nazarenko, L. Constraining human contributions to observed warming since the pre-industrial period. Nature Climate Change 2021, 11, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslin, M.; Ramnath, R.D.; Welsh, G.I.; Sisodiya, S.M. Understanding the health impacts of the climate crisis. Future Healthcare Journal 2025, 12, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawzy, S.; Osman, A.I.; Doran, J.; Rooney, D.W. Strategies for mitigation of climate change: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2020, 18, 2069–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivanna, K.R. Climate change and its impact on biodiversity and human welfare. Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy 2022, 88, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, W.; Rogage, K.; Martinez, P.; Kassem, M. Decarbonising construction equipment: Management practices and strategies for net zero in UK infrastructure projects. Building and Environment 2025, 270, 112503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S. Decarbonisation of Road Transportation in India—A Round-Robin Review on Low-Carbon Strategies and Financial Policies. Future Transportation 2025, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanada, K.; Zappa, M. Japan’s international cooperation on smart city development in Asia: International effort beneath the smart rhetoric in India and in Thailand. Research in Globalization 2025, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleeb, H.; El-Rifaie, A.M.; Youssef, A.A.; Mohamed, S.A.; Kassem, R. Providing Solutions to Decarbonize Energy-Intensive Industries for a Sustainable Future in Egypt by 2050. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PPIAF. ToolkiT for Public-PrivaTe ParTnershiPs in roads & highways; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, L.; Arbabi, H.; Sobhiyah, M.H.; Laali, A. Investigation of factors affecting sustainability in public–private partnerships for infrastructure projects. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2024, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipu, W.A.; Mughal, Y.H.; Kundi, G.M.; Nair, K.S.; Thurasamy, R. Enhancing the Sustainable Performance of Public–Private Partnership Projects: The Buffering Effect of Environmental Uncertainty. Buildings 2024, 14, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Hallo, L.; Gunawan, I. Investigating risk of public–private partnerships (PPPs) for smart transportation infrastructure project development. Built Environment Project and Asset Management 2024, 14, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, F.K.; Al-Jadhai, S.; Alromihy, H.; Alsaud, M.; Sherif, M.; Mohamed, A.G. Appraising critical success factors in sustainable housing projects: A comparative study of PPP modalities in Saudi Arabia. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Ampratwum, G. Developing a Model for Assessing the Performance Outcome for Building Urban Community Resilience Through Public–Private Partnership. Buildings 2025, 15, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Li, W.; Li, D.; Peng, J. Public–private partnerships and carbon reduction targets: evidence from PPP investments in energy and environmental protection in China. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2025, 27, 6567–6597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Zhang, X. A critical analysis of water PPP failures in sub-Saharan Africa. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2022, 29, 3157–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Li, S.; Kang, A.; Corlett, R.T.; Ma, K.; Shen, X. Biodiversity risk assessment and management for infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative. Conservation Biology 2025, e70039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.M.; Nguyen, H.H.; Pham, H.C.; Nguyen, L.H. Engage or retreat? Exploring the determinants of participation in Climate Finance public-private partnerships. Clim. Change 2024, 177, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuffour, P.; Chen, G.; Opoku-Mensah, E.; Darko, P.A.; Adu Agyapong, R. Toward sustainable development: Developing a decision-making framework for cross-sectoral engagement in green procurement. Sustainable Development 2024, 32, 2233–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Fu, J.; Xu, Y.; Sun, L. How does contract flexibility affect the sustainability performance of public–private partnership projects? A serial multiple mediator model. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2024, 31, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, L.; Ma, L. Effect of public–private partnership features on contractual complexity: evidence from China. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2024, 31, 3876–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Mufti, N.A.; Mubin, S.; Saleem, M.Q.; Zahoor, S.; Ullah, S. Identification of various execution modes and their respective risks for public–private partnership (PPP) infrastructure projects. Buildings 2023, 13, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarri, K.; Boussabaine, H. Critical success factors for public–private partnerships in smart city infrastructure projects. Constr. Innov. 2025, 25, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampratwum, G.; Tam, V.W.; Osei-Kyei, R. Critical analysis of risks factors in using public-private partnership in building critical infrastructure resilience: a systematic review. Constr. Innov. 2023, 23, 360–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, H.C.; Leendertse, W.; Volker, L. Mechanisms for protecting returns on private investments in public infrastructure projects. International Journal of Project Management 2022, 40, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Dzagli, J.R.A.D.; Eluerkeh, K.; Bonsu, F.B.; Opoku-Brafi, S.; Gyimah, S.; Asuming, N.A.S.; Atibila, D.W.; Kukah, A.S. A systematic review of artificial intelligence in managing climate risks of PPP infrastructure projects. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2025, 32, 2430–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Park, C.Y.; Lee, D.K.; Yun, S.H.; Hyun, J.H.; Kim, E.S. The cooling effect of trees in high-rise building complexes in relation to spatial distance from buildings. Sustainable Cities and Society 2024, 114, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiahou, X.; Tang, L.; Yuan, J.; Zuo, J.; Li, Q. Exploring social impacts of urban rail transit PPP projects: Towards dynamic social change from the stakeholder perspective. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 93, 106700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, L.d.; Ter-Minassian, T. Subnational investments in mitigation and adaptation to climate change: some financing and governance issues. Public Finance and Management 2024, 23, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abden, M.J.; Tao, Z.; Alim, M.A.; Afroze, J.D.; Tam, V.W.Y. Enhancing building energy performance and climate resilience with phase change materials and reflective coatings. Journal of Energy Storage 2025, 120, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, A.T.D.; Javanroodi, K.; Nik, V.M. Climate resilient interconnected infrastructure: Co-optimization of energy systems and urban morphology. Applied Energy 2021, 285, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafermos, Y.; Gabor, D.; Michell, J. The Wall Street Consensus in pandemic times: what does it mean for climate-aligned development? Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue canadienne d’études du développement 2021, 42, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi Shahdadi, L.; Aminnejad, B.; Sarvari, H.; Chan, D.W. Determining the critical risk factors of implementing public–private partnership in water and wastewater infrastructure facilities: Perspectives of private and public partners in Iran. Buildings 2023, 13, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, D.T.; Toan, N.Q.; Van Tam, N. Critical success factors for implementing PPP infrastructure projects in developing countries: the case of Vietnam. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2022, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, N.C.; Jiménez, A.; Bayraktar, S.; Tsagdis, D. Climate risk and private participation projects in infrastructure: Mitigating the impact of locational (dis) advantages. Management Decision 2021, 59, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeft, M.; Pieper, M.; Eriksson, K.; Bargstädt, H.-J. Toward life cycle sustainability in infrastructure: the role of automation and robotics in PPP projects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casady, C.B.; Cepparulo, A.; Giuriato, L. Public-private partnerships for low-carbon, climate-resilient infrastructure: Insights from the literature. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 470, 143338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, S.; Suriyagoda, N. Climate risks and resilience in infrastructure PPPs: issues to be considered. World Bank Group 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. Mapping studies on sustainability in the performance measurement of public-private partnership projects: a systematic review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Jiang, J.; Martek, I.; Jiang, W. Critical risk management strategies for the operation of public–private partnerships: a vulnerability perspective of infrastructure projects. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2025, 32, 4771–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khahro, S.H.; Ali, T.H.; Hassan, S.; Zainun, N.Y.; Javed, Y.; Memon, S.A. Risk severity matrix for sustainable public-private partnership projects in developing countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. A holistic review of research studies on financial risk management in public–private partnership projects. Engineering, construction and architectural management 2021, 28, 2549–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, H. Exploring risk factors affecting sustainable outcomes of global public–private partnership (PPP) projects: a stakeholder perspective. Buildings 2023, 13, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasena, N.S.; Chan, D.W.; Kumaraswamy, M. A systematic literature review and analysis towards developing PPP models for delivering smart infrastructure. Built Environment Project and Asset Management 2021, 11, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Guo, X.; Wei, B.; Chen, B. A fuzzy analytic hierarchy process for risk evaluation of urban rail transit PPP projects. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems 2021, 41, 5117–5128. [Google Scholar]

- Arijeloye, B.T.; Aje, I.O.; Oke, A.E. Evaluating the key risk factors in PPP-procured mass housing projects in Nigeria: A Delphi study of industry experts. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology 2024, 22, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M.; Elsworth, G.R.; Hoban, E.; Osborne, R.H. Questionnaire validation practice within a theoretical framework: a systematic descriptive literature review of health literacy assessments. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Tumpa, R.J.; Ofori, J.A.N.; Botchway, B.; Tetteh, P.A.; Jin, X. Critical success factors of green finance on zero carbon buildings. Energy Build. 2025, 338, 115735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.; Javed, A.A.; Ameyaw, E.E. Critical success criteria for public-private partnership projects: international experts’ opinion. International Journal of Strategic Property Management 2017, 21, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European business review 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Ramayah, T.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. PLS-SEM statistical programs: a review. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling 2021, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purwanto, A.; Sudargini, Y. Partial least squares structural squation modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis for social and management research: a literature review. Journal of Industrial Engineering & Management Research 2021, 2, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Machuca, M.; Martínez Costa, C. Exploring critical success factors of knowledge management projects in the consulting sector. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 2012, 23, 1297–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maroof, R.A.S.; Al-Emran, M. Students acceptance of Google classroom: An exploratory study using PLS-SEM approach. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, R.C.; Vafaei-Zadeh, A.; Hanifah, H.; Ramayah, T. Investigating factors influencing individual user’s intention to adopt cloud computing: a hybrid approach using PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 4470–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Singh, V.V.; Gupta, A.K.; Kapur, P. Assessing e-learning platforms in higher education with reference to student satisfaction: a PLS-SEM approach. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2024, 15, 4885–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Lau, R.S.; Wang, L.C. Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia pacific journal of management 2024, 41, 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, A.; Durach, C.F.; Kembro, J.; Treiblmaier, H. Statistical and judgmental criteria for scale purification. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 2017, 22, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Matthews, L.M.; Ringle, C.M. Identifying and treating unobserved heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: part I–method. European Business Review 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, G.; Roldán, J.L.; Sabol, M.; Hair, J.; Chong, A.Y.L. Emerging opportunities for information systems researchers to expand their PLS-SEM analytical toolbox. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2024, 124, 2230–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaithilingam, S.; Ong, C.S.; Moisescu, O.I.; Nair, M.S. Robustness checks in PLS-SEM: A review of recent practices and recommendations for future applications in business research. Journal of Business Research 2024, 173, 114465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GovUK. More than 30 companies fined as part of efforts to reduce emissions. 2022.

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, X.; Zhao, N.; Sun, J. Risk allocation and benefit distribution of PPP projects for construction waste recycling: a case study of China. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2023, 30, 3927–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martimort, D.; Straub, S. How to design infrastructure contracts in a warming world: A critical appraisal of public–private partnerships. International Economic Review 2016, 57, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.-C.; Ding, J.-Y.; Xie, S.-C.; Li, Y.; Akiyama, M.; Lu, Y.; Beer, M.; Li, J. Climate change impacts on the risk assessment of concrete civil infrastructures. ASCE OPEN: Multidisciplinary Journal of Civil Engineering 2024, 2, 03124001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent variables | Code | Indicator/measurement variables | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Project identification strategies | PIS | ||

| PIS1 | Set achievable climate risk targets | Akhtar, et al. [48] | |

| PIS2 | Develop timelines on the actions to reduce carbon emissions | Almarri and Boussabaine [49] | |

| PIS3 | Get leadership support to the decarbonisation roadmap | Ampratwum, et al. [50] | |

| PIS4 | Define the performance assessment targets | Demirel, et al. [51] | |

| PIS5 | Specify the scope of climate risks | Akomea-Frimpong, et al. [52] | |

| Feasibility assessment strategies | FSS | ||

| FSS1 | Carbon emission footprint assessment | Kim, et al. [53] | |

| FSS2 | Retrofitting and redesign of infrastructures | Xiahou, et al. [54] | |

| FSS3 | Compute the potential costs on each climate action | Mello and Ter-Minassian [55] | |

| FSS4 | Assess the appropriate clean energy tools | Abden, et al. [56] | |

| FSS5 | Determine the applicability of climate risk models | Perera, et al. [57] | |

| FSS6 | Justify the benefits of measures against climate risks | Dafermos, et al. [58] | |

| Procurement strategies | PRS | ||

| PRS1 | Climate-friendly supply chains | Moradi Shahdadi, et al. [59] | |

| PRS2 | Carbon neutral bidding measures | Hai, et al. [60] | |

| PRS3 | Green procurement policies | Lupton, et al. [61] | |

| PRS4 | Strong partnership with suppliers | Akomea-Frimpong, Agyekum, Amoakwa, Babon-Ayeng and Pariafsai [4] | |

| PRS5 | Circular procurement initiatives | Wang, Liu and Zhou [6] | |

| PRS6 | Real-time procurement tracking systems | Hoeft, et al. [62] | |

| Contract award strategies | CAS | ||

| CAS1 | Climate-conscious contracts | Nguyen, Hallo and Gunawan [38] | |

| CAS2 | Commitment to implement climate risk management practices | Casady, et al. [63] | |

| CAS3 | Contract clauses ensure meeting decarbonisation targets | Sundararajan and Suriyagoda [64] | |

| CAS4 | Incorporate sustainability requirements | Akomea-Frimpong, et al. [65] | |

| CAS5 | Select the lowest climate risk contract | Jiang, et al. [66] | |

| Contract management strategies | CMS | ||

| CMS1 | Implement climate resilience and adaptation measures | Khahro, et al. [67] | |

| CMS2 | Utilise renewable energies for infrastructures | Akomea-Frimpong, et al. [68] | |

| CMS3 | Upskill teams towards net-zero project management | Li and Wang [69] | |

| CM4 | Emission reduction monitoring systems | Jayasena, et al. [70] | |

| CM5 | Review of contract risks | Feng, et al. [71] | |

| CM6 | Establish climate-based governance structures | Arijeloye, et al. [72] |

| Category | Profile and number of respondents |

| Job position | Risk consultant (24), Project manager (45), Public regulator (18), Architect (31), Operator (29) |

| Education | Diploma (25), First degree (74), master’s degree (38), Doctoral degree (10) |

| Experience | 0 to 5 years (12), 6 to 10 years (94), more than 10 years (41) |

| Project type | Roads (33), Hospitals (24), Energy & electricity (37), Housing (53) |

| Country | Australia (7), India (34), Ghana (27), Nigeria (18), US (8), UK (6), Kenya (23), Canada (5), South Africa (9), China (10) |

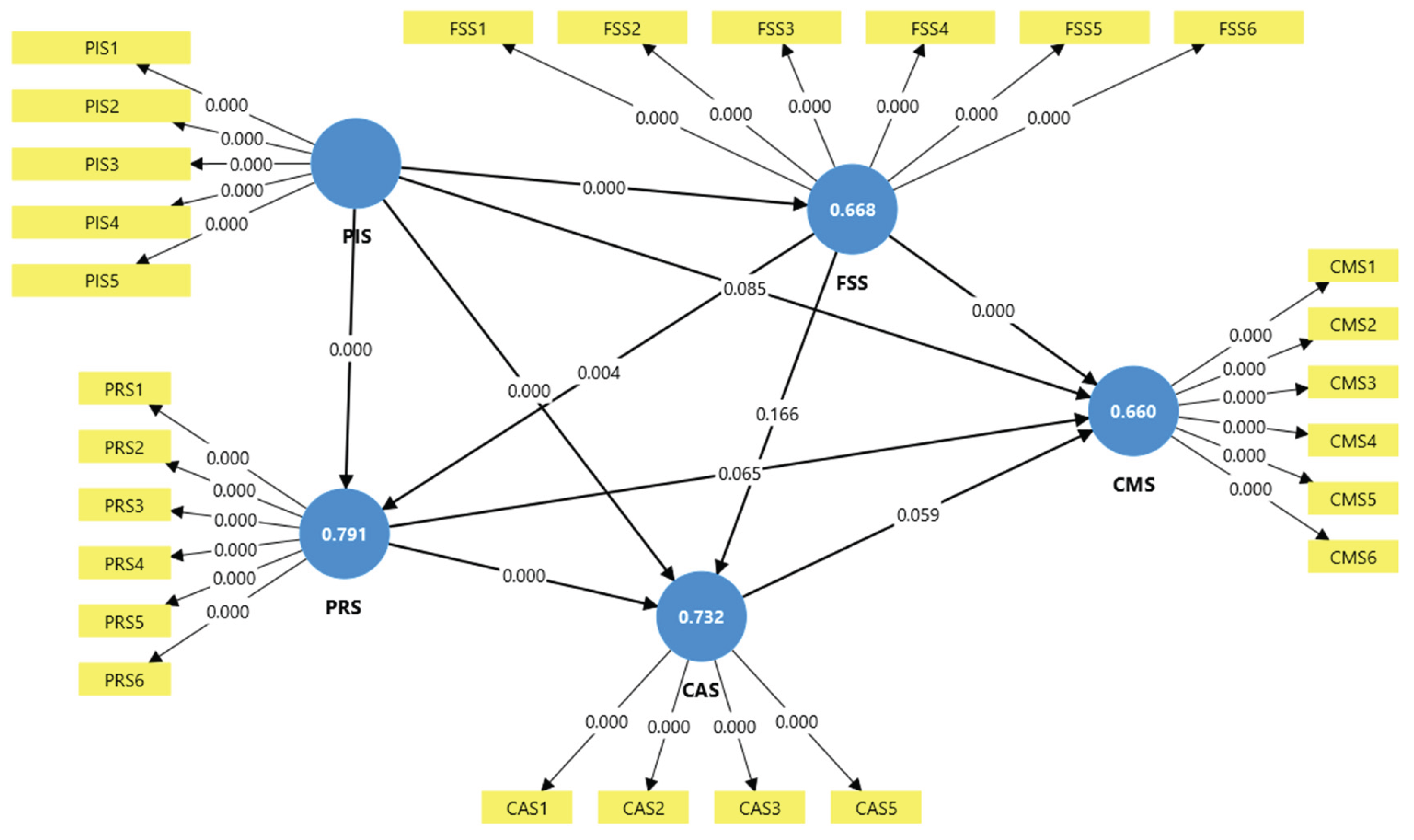

| Hypotheses | Path coefficient | T- Stat | P values | Decision |

| H1 (PIS -> FSS) | 0.817 | 22.657 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 (PIS -> CMS) | -0.426 | 1.725 | 0.085 | Reject |

| H3 (PIS -> CAS) | 1.238 | 6.157 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 (PIS -> PRS) | 1.070 | 16.121 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 (FSS -> PRS) | -0.233 | 2.870 | 0.004 | Supported |

| H6 (FSS -> CAS) | 0.150 | 1.385 | 0.166 | Reject |

| H7 (FSS -> CMS) | 0.708 | 7.014 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H8 (PRS -> CAS) | -0.659 | 4.611 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H9 (PRS -> CMS) | 0.331 | 1.844 | 0.065 | Reject |

| H10 (CAS -> CMS) | 0.299 | 1.892 | 0.059 | Reject |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).