Submitted:

17 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

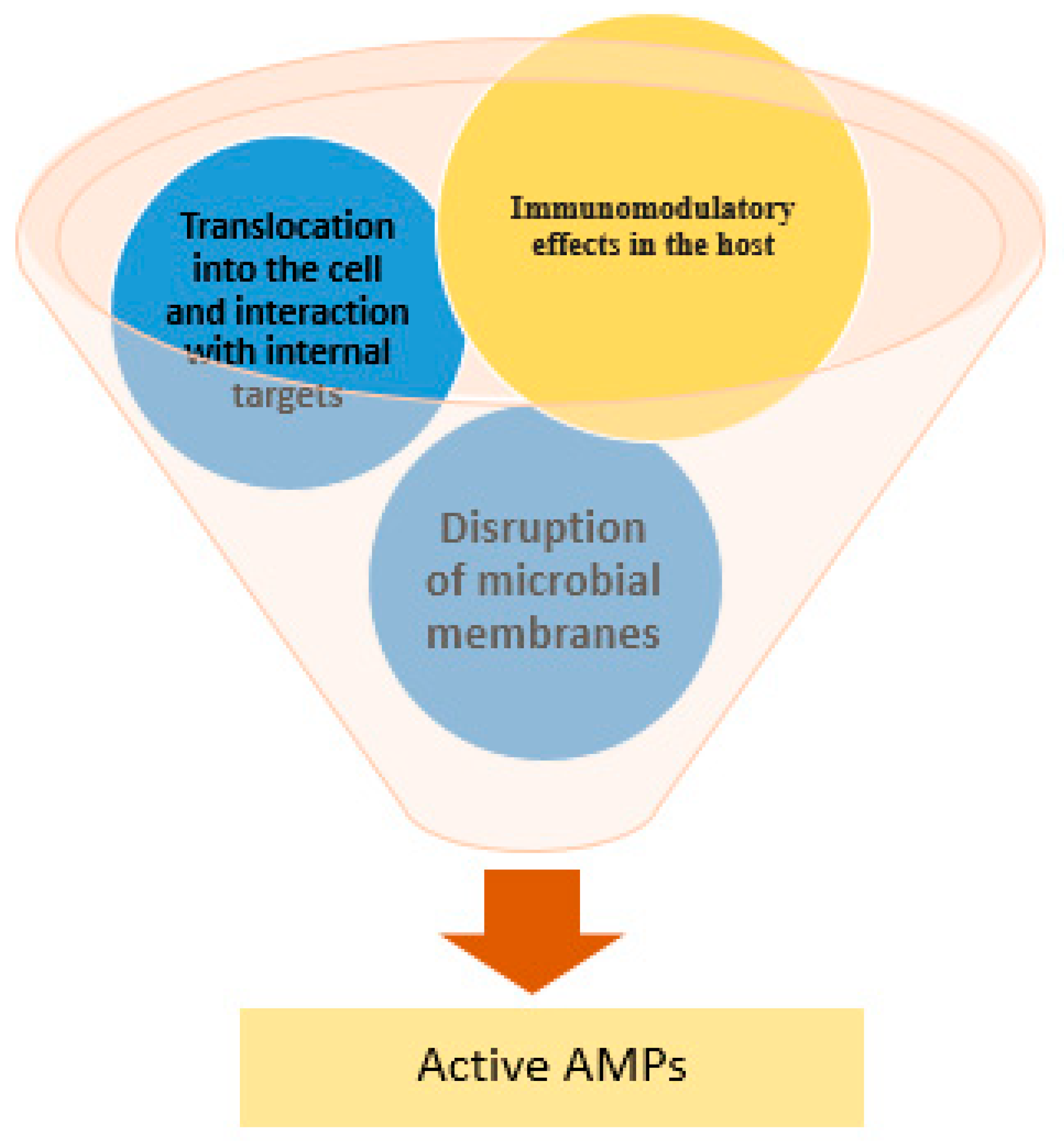

2. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Peptide Action

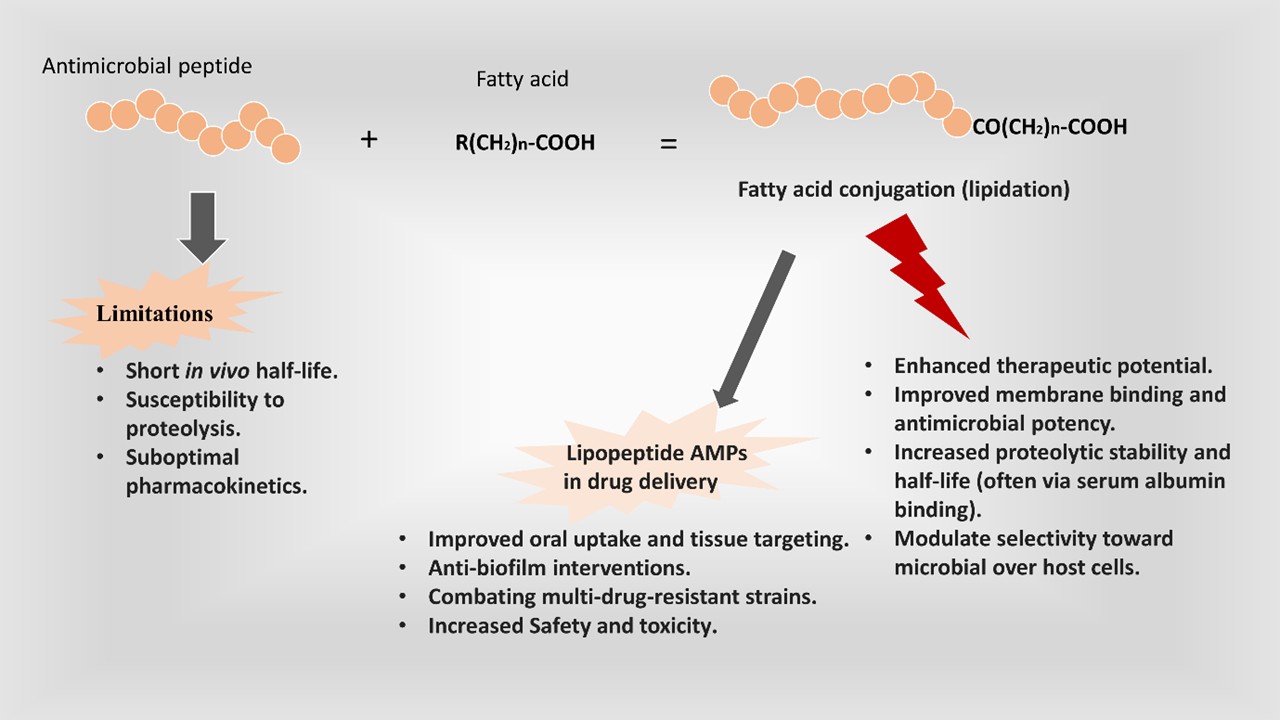

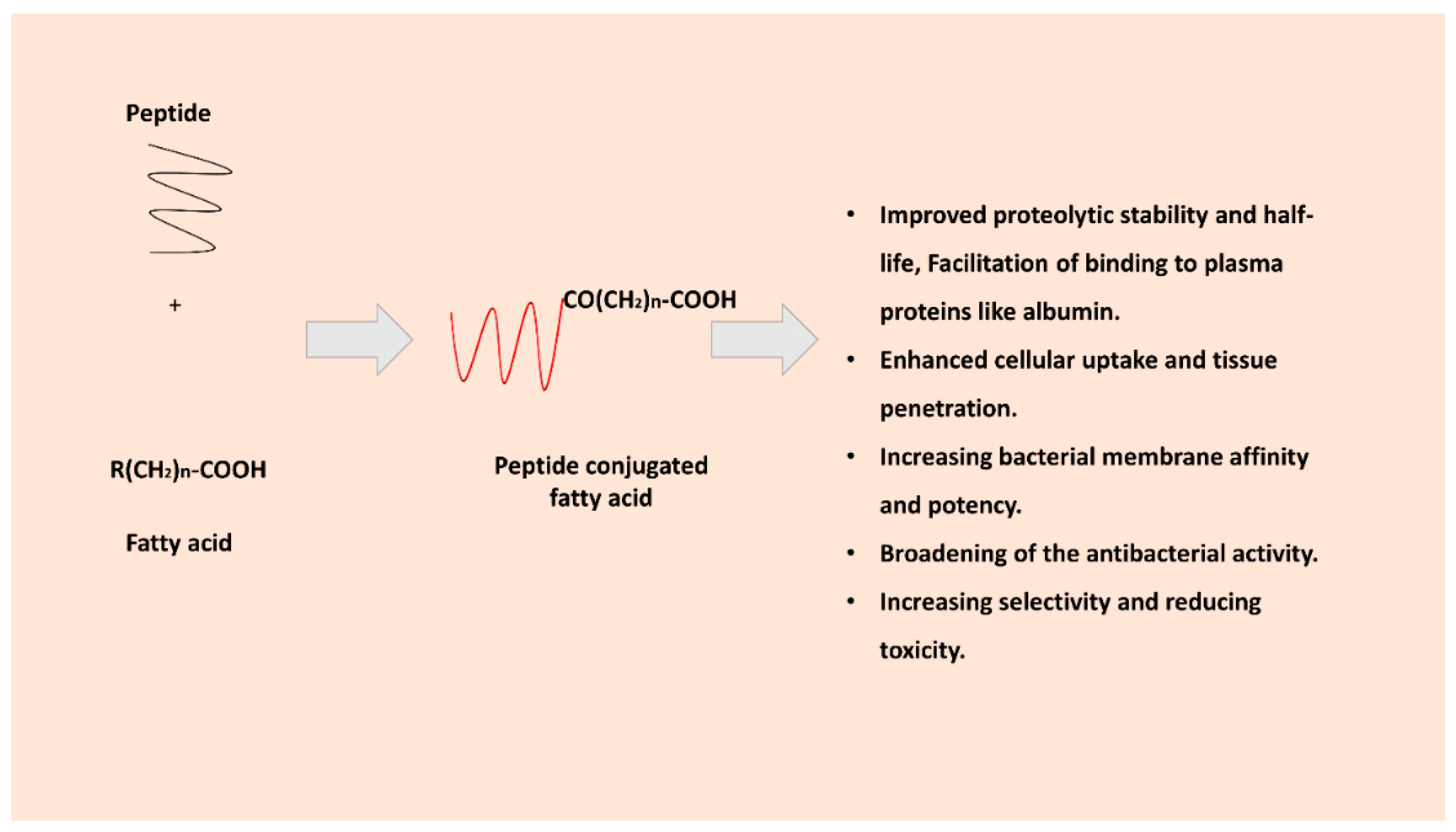

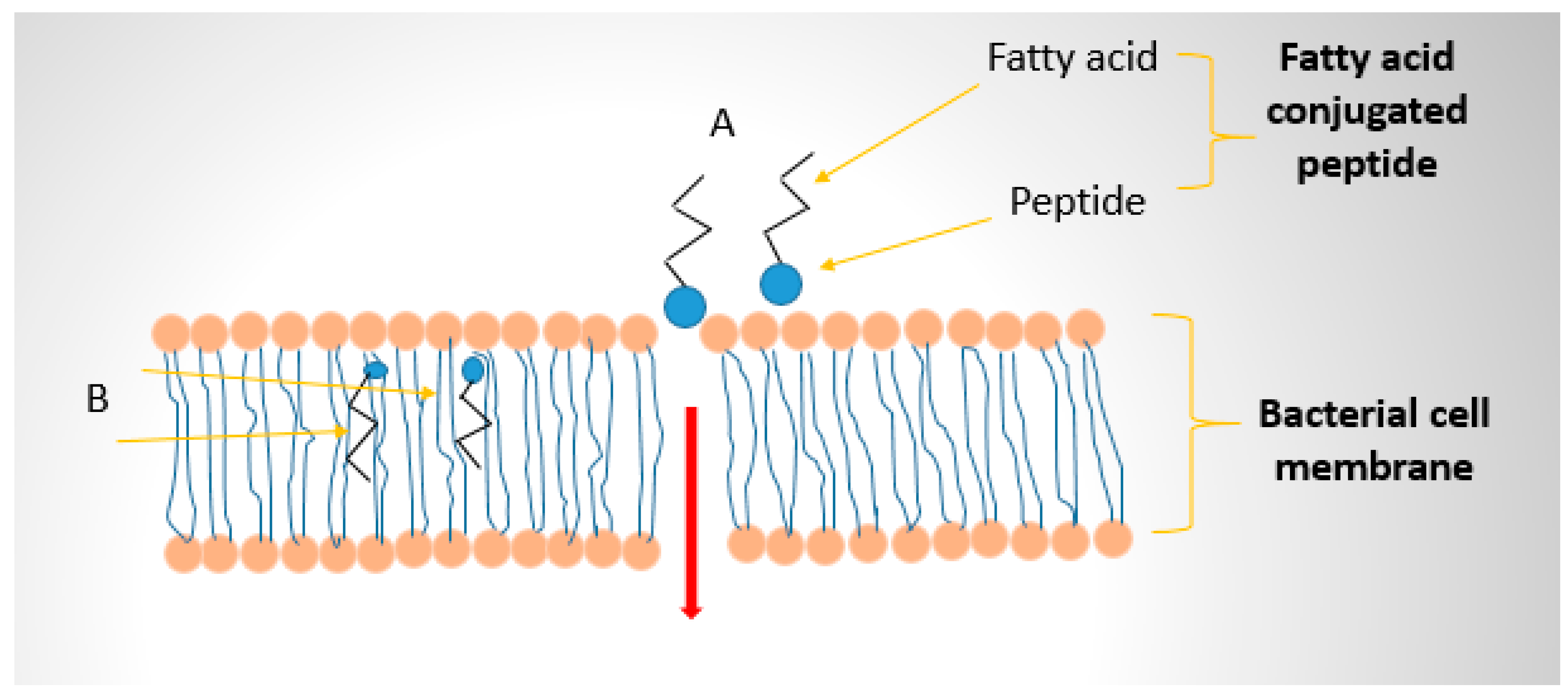

3. Role and Rationale for Fatty Acid Conjugation to AMPs

3.1. Improving Proteolytic Stability and Half-Life

3.2. Enhanced Cellular Uptake and Tissue Penetration

3.3. Increasing Membrane Affinity and Potency

3.4. Increasing Selectivity and Reducing Toxicity

4. Applications in Drug Delivery, Biofilms, and Resistant Strains

4.1. Enhanced Drug Delivery and Pharmacokinetics

4.2. Anti-Biofilm Activity

4.3. Combating Resistant Strains

4.4. Topical and Targeted Applications

5. Safety and Toxicity Considerations

5.1. Hemolysis and Cytotoxicity

5.2. Immune Response and Allergenicity

5.3. In Vivo Toxicity and Pharmacology

5.4. Bacterial Resistance to FAMPs

5.5. Mitigating Toxicity

6. Future Perspectives

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.S.; Wong, C.T.H.; Aung, T.T.; Lakshminarayanan, R.; Mehta, J.S.; Rauz, S.; McNally, A.; Kintses, B.; Peacock, S.J.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance: a concise update. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 100947. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance; 2014.

- Guan, L.; Beig, M.; Wang, L.; Navidifar, T.; Moradi, S.; Motallebi Tabaei, F.; Teymouri, Z.; Abedi Moghadam, M.; Sedighi, M. Global status of antimicrobial resistance in clinical Enterococcus faecalis isolates: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2024, 23, 80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelalcha, B.D.; Gelgie, A.E.; Kerro Dego, O. Antimicrobial resistance and prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella species in East Tennessee dairy farms. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e0353723. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, M.; Ovsepian, A.; Leekitcharoenphon, P.; Seyfarth, A.M.; Mordhorst, H.; Otani, S.; Koeberl-Jelovcan, S.; Milanov, M.; Kompes, G.; Liapi, M.; et al. Azithromycin resistance in Escherichia coli and Salmonella from food-producing animals and meat in Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother 2024, 79, 1657-1667. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehari, M.G.; Yeshiwas, A.G.; Esubalew, D.; Azmeraw, Y.; Delie, A.M.; Limenh, L.W.; Worku, N.K.; Hailu, M.; Melese, M.; Abie, A.; et al. Dominance of antimicrobial resistance bacteria and risk factors of bacteriuria infection among pregnant women in East Africa: implications for public health. J Health Popul Nutr 2025, 44, 98. [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, A.S.; Franconeri, L.; Page, S.; Myhre, A.E.; Tornes, R.A.; Kacelnik, O.; Bjørnholt, J.V. Clinical outcomes of antimicrobial resistance in cancer patients: a systematic review of multivariable models. BMC Infect Dis 2023, 23, 247. [CrossRef]

- Ntim, O.K.; Awere-Duodu, A.; Osman, A.H.; Donkor, E.S. Antimicrobial resistance of bacterial pathogens isolated from cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2025, 25, 296. [CrossRef]

- Bucataru, C.; Ciobanasu, C. Antimicrobial peptides: Opportunities and challenges in overcoming resistance. Microbiol Res 2024, 286, 127822. [CrossRef]

- Girdhar, M.; Sen, A.; Nigam, A.; Oswalia, J.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, R. Antimicrobial peptide-based strategies to overcome antimicrobial resistance. Arch Microbiol 2024, 206, 411. [CrossRef]

- Gani, Z.; Kumar, A.; Raje, M.; Raje, C.I. Antimicrobial peptides: An alternative strategy to combat antimicrobial resistance. Drug Discovery Today 2025, 30, 104305. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbediwi, M.; Rolff, J. Metabolic pathways and antimicrobial peptide resistance in bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 2024, 79, 1473-1483. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Xu, H.; Xia, J.; Ma, J.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Feng, J. D- and Unnatural Amino Acid Substituted Antimicrobial Peptides With Improved Proteolytic Resistance and Their Proteolytic Degradation Characteristics. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 563030. [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Wang, J.; Peng, J.; Zhao, P.; Kong, Z.; Wang, K.; Yan, W.; Wang, R. D-amino acid substitution enhances the stability of antimicrobial peptide polybia-CP. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2017, 49, 916-925. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, L.Y.; Zhang, V.M.; Huang, Y.H.; Waters, N.C.; Bansal, P.S.; Craik, D.J.; Daly, N.L. Cyclization of the antimicrobial peptide gomesin with native chemical ligation: influences on stability and bioactivity. Chembiochem 2013, 14, 617-624. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yang, Y.; Li, R.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z.; Deng, Q.; Dong, S. N-terminal acetylation of antimicrobial peptide L163 improves its stability against protease degradation. J Pept Sci 2021, 27, e3337. [CrossRef]

- Lohan, S.; Konshina, A.G.; Mohammed, E.H.M.; Helmy, N.M.; Jha, S.K.; Tiwari, R.K.; Maslennikov, I.; Efremov, R.G.; Parang, K. Impact of stereochemical replacement on activity and selectivity of membrane-active antibacterial and antifungal cyclic peptides. NPJ Antimicrob Resist 2025, 3, 56. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, E.H.M.; Lohan, S.; Ghaffari, T.; Gupta, S.; Tiwari, R.K.; Parang, K. Membrane-Active Cyclic Amphiphilic Peptides: Broad-Spectrum Antibacterial Activity Alone and in Combination with Antibiotics. J Med Chem 2022, 65, 15819-15839. [CrossRef]

- Lohan, S.; Konshina, A.G.; Efremov, R.G.; Maslennikov, I.; Parang, K. Structure-Based Rational Design of Small α-Helical Peptides with Broad-Spectrum Activity against Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens. J Med Chem 2023, 66, 855-874. [CrossRef]

- Lohan, S.; Konshina, A.G.; Tiwari, R.K.; Efremov, R.G.; Maslennikov, I.; Parang, K. Broad-spectrum activity of membranolytic cationic macrocyclic peptides against multi-drug resistant bacteria and fungi. Eur J Pharm Sci 2024, 197, 106776. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, E.H.M.; Lohan, S.; Tiwari, R.K.; Parang, K. Amphiphilic cyclic peptide [W(4)KR(5)]-Antibiotics combinations as broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents. Eur J Med Chem 2022, 235, 114278. [CrossRef]

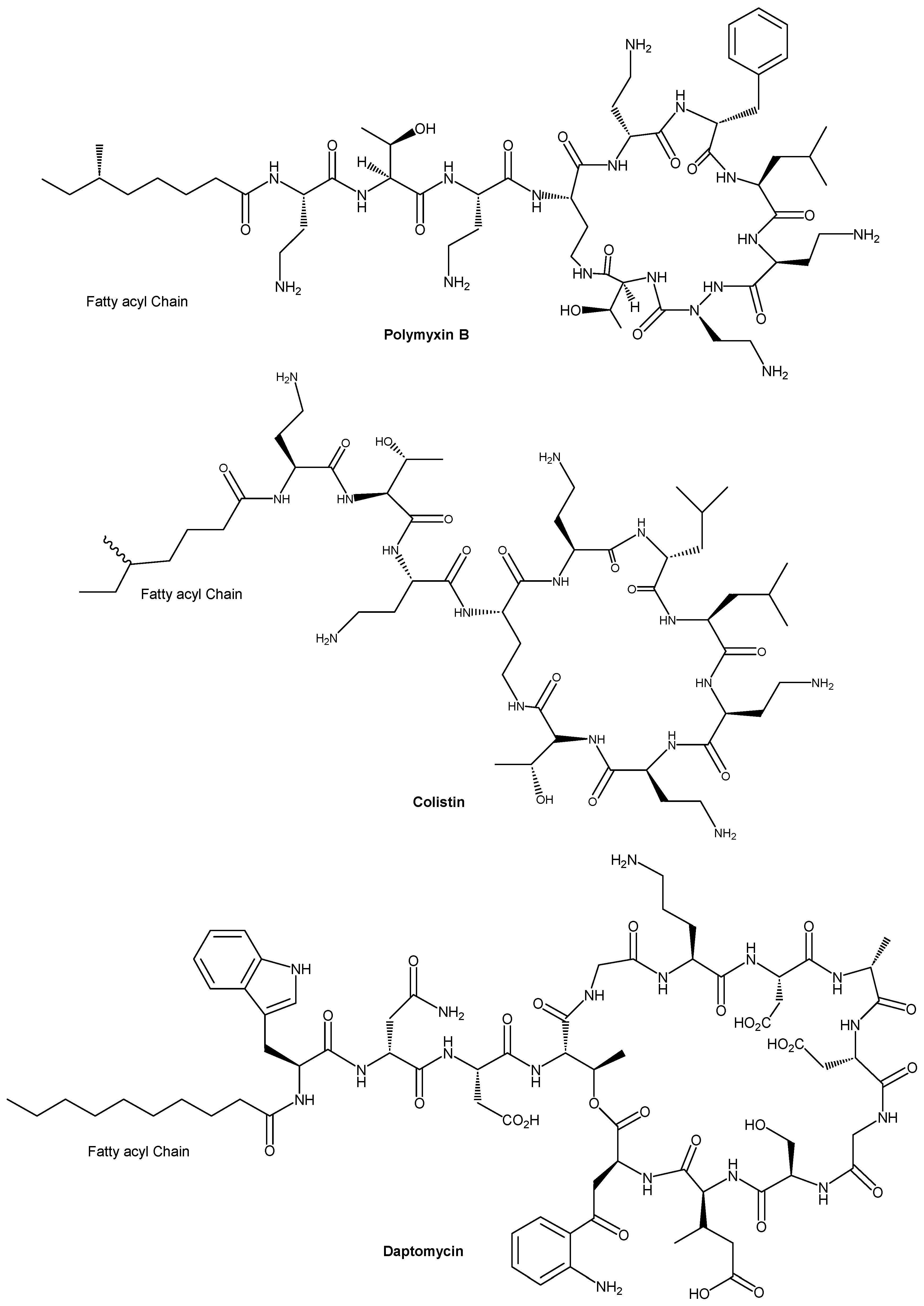

- Reid, D.J.; Dash, T.; Wang, Z.; Aspinwall, C.A.; Marty, M.T. Investigating Daptomycin-Membrane Interactions Using Native MS and Fast Photochemical Oxidation of Peptides in Nanodiscs. Anal Chem 2023, 95, 4984-4991. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledger, E.V.K.; Sabnis, A.; Edwards, A.M. Polymyxin and lipopeptide antibiotics: membrane-targeting drugs of last resort. Microbiology (Reading) 2022, 168. [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed Ahmed, M.A.E.; Zhong, L.L.; Shen, C.; Yang, Y.; Doi, Y.; Tian, G.B. Colistin and its role in the Era of antibiotic resistance: an extended review (2000-2019). Emerg Microbes Infect 2020, 9, 868-885. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtzhals, P.; Østergaard, S.; Nishimura, E.; Kjeldsen, T. Derivatization with fatty acids in peptide and protein drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2023, 22, 59-80. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Song, H.; Wang, X.; Shen, H.; Li, S.; Guan, X. Fatty acids-modified liposomes for encapsulation of bioactive peptides: Fabrication, characterization, storage stability and in vitro release. Food Chemistry 2024, 440, 138139. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.K.; Jackman, J.A.; Valle-González, E.R.; Cho, N.-J. Antibacterial Free Fatty Acids and Monoglycerides: Biological Activities, Experimental Testing, and Therapeutic Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 1114. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangoni, M.L.; Shai, Y. Short native antimicrobial peptides and engineered ultrashort lipopeptides: similarities and differences in cell specificities and modes of action. Cell Mol Life Sci 2011, 68, 2267-2280. [CrossRef]

- Kamysz, E.; Sikorska, E.; Jaśkiewicz, M.; Bauer, M.; Neubauer, D.; Bartoszewska, S.; Barańska-Rybak, W.; Kamysz, W. Lipidated Analogs of the LL-37-Derived Peptide Fragment KR12-Structural Analysis, Surface-Active Properties and Antimicrobial Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumari, V.; Nagaraj, R. N-Terminal fatty acylation of peptides spanning the cationic C-terminal segment of bovine β-defensin-2 results in salt-resistant antibacterial activity. Biophys Chem 2015, 199, 25-33. [CrossRef]

- K, R.G.; Balenahalli Narasingappa, R.; Vishnu Vyas, G. Unveiling mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide: Actions beyond the membranes disruption. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38079. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shai, Y. Mechanism of the binding, insertion and destabilization of phospholipid bilayer membranes by alpha-helical antimicrobial and cell non-selective membrane-lytic peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999, 1462, 55-70. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, D.G. Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) with Dual Mechanisms: Membrane Disruption and Apoptosis. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2015, 25, 759-764. [CrossRef]

- Oren, Z.; Shai, Y. Mode of action of linear amphipathic alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers 1998, 47, 451-463. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Booth, V. Antimicrobial Peptide Mechanisms Studied by Whole-Cell Deuterium NMR. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 2740. [CrossRef]

- Vejzovic, D.; Piller, P.; Cordfunke, R.A.; Drijfhout, J.W.; Eisenberg, T.; Lohner, K.; Malanovic, N. Where Electrostatics Matter: Bacterial Surface Neutralization and Membrane Disruption by Antimicrobial Peptides SAAP-148 and OP-145. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Khavani, M.; Mehranfar, A.; Mofrad, M.R.K. Antimicrobial peptide interactions with bacterial cell membranes. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2025, 43, 4615-4628. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatansever, F.; de Melo, W.C.M.A.; Avci, P.; Vecchio, D.; Sadasivam, M.; Gupta, A.; Chandran, R.; Karimi, M.; Parizotto, N.A.; Yin, R.; et al. Antimicrobial strategies centered around reactive oxygen species – bactericidal antibiotics, photodynamic therapy, and beyond. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2013, 37, 955-989. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zughaier, S.M.; Shafer, W.M.; Stephens, D.S. Antimicrobial peptides and endotoxin inhibit cytokine and nitric oxide release but amplify respiratory burst response in human and murine macrophages. Cell Microbiol 2005, 7, 1251-1262. [CrossRef]

- Niyonsaba, F.; Nagaoka, I.; Ogawa, H. Human defensins and cathelicidins in the skin: beyond direct antimicrobial properties. Crit Rev Immunol 2006, 26, 545-576. [CrossRef]

- Guaní-Guerra, E.; Santos-Mendoza, T.; Lugo-Reyes, S.O.; Terán, L.M. Antimicrobial peptides: general overview and clinical implications in human health and disease. Clin Immunol 2010, 135, 1-11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofton, H.; Pränting, M.; Thulin, E.; Andersson, D.I. Mechanisms and Fitness Costs of Resistance to Antimicrobial Peptides LL-37, CNY100HL and Wheat Germ Histones. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e68875. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assoni, L.; Milani, B.; Carvalho, M.R.; Nepomuceno, L.N.; Waz, N.T.; Guerra, M.E.S.; Converso, T.R.; Darrieux, M. Resistance Mechanisms to Antimicrobial Peptides in Gram-Positive Bacteria. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 593215. [CrossRef]

- Nawrocki, K.L.; Crispell, E.K.; McBride, S.M. Antimicrobial Peptide Resistance Mechanisms of Gram-Positive Bacteria. Antibiotics (Basel) 2014, 3, 461-492. [CrossRef]

- Ryberg, L.A.; Sønderby, P.; Barrientos, F.; Bukrinski, J.T.; Peters, G.H.J.; Harris, P. Solution structures of long-acting insulin analogues and their complexes with albumin. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 2019, 75, 272-282. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Zhu, N.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, T.; Gou, S.; Xie, J.; Yao, J.; Ni, J. Antimicrobial peptides conjugated with fatty acids on the side chain of D-amino acid promises antimicrobial potency against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Eur J Pharm Sci 2020, 141, 105123. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Cui, Y.; Zhangsun, D.; Luo, S. Fatty acid chain modification enhances the serum stability of antimicrobial peptide B1 and activities against Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Bioorg Chem 2025, 154, 108015. [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.; Bloch, P.; Schäffer, L.; Pettersson, I.; Spetzler, J.; Kofoed, J.; Madsen, K.; Knudsen, L.B.; McGuire, J.; Steensgaard, D.B.; et al. Discovery of the Once-Weekly Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Analogue Semaglutide. J Med Chem 2015, 58, 7370-7380. [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, L.B.; Lau, J. The Discovery and Development of Liraglutide and Semaglutide. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10, 155. [CrossRef]

- Kiran, G.S.; Priyadharsini, S.; Sajayan, A.; Priyadharsini, G.B.; Poulose, N.; Selvin, J. Production of Lipopeptide Biosurfactant by a Marine Nesterenkonia sp. and Its Application in Food Industry. Frontiers in Microbiology 2017, Volume 8 - 2017. [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Oliver, M.; Santander-Ortega, M.J.; Lozano, M.V. Current approaches in lipid-based nanocarriers for oral drug delivery. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2021, 11, 471-497. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trier, S.; Linderoth, L.; Bjerregaard, S.; Strauss, H.M.; Rahbek, U.L.; Andresen, T.L. Acylation of salmon calcitonin modulates in vitro intestinal peptide flux through membrane permeability enhancement. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2015, 96, 329-337. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, D.; Nasrolahi Shirazi, A.; Northup, K.; Sullivan, B.; Tiwari, R.K.; Bisoffi, M.; Parang, K. Enhanced cellular uptake of short polyarginine peptides through fatty acylation and cyclization. Mol Pharm 2014, 11, 2845-2854. [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, S.P.; Chen, J.Y. Conjugation of antimicrobial peptides to enhance therapeutic efficacy. Eur J Med Chem 2023, 259, 115680. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikorska, E.; Stachurski, O.; Neubauer, D.; Małuch, I.; Wyrzykowski, D.; Bauer, M.; Brzozowski, K.; Kamysz, W. Short arginine-rich lipopeptides: From self-assembly to antimicrobial activity. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2018, 1860, 2242-2251. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, I.A.; Elliott, A.G.; Kavanagh, A.M.; Zuegg, J.; Blaskovich, M.A.; Cooper, M.A. Contribution of amphipathicity and hydrophobicity to the antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity of β-hairpin peptides. ACS infectious diseases 2016, 2, 442-450. [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Zhu, X.; Wang, J.; Dong, N.; Shan, A. Novel design of heptad amphiphiles to enhance cell selectivity, salt resistance, antibiofilm properties and their membrane-disruptive mechanism. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2017, 60, 2257-2270. [CrossRef]

- Avrahami, D.; Shai, Y. Conjugation of a magainin analogue with lipophilic acids controls hydrophobicity, solution assembly, and cell selectivity. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 2254-2263. [CrossRef]

- Avrahami, D.; Shai, Y. Bestowing antifungal and antibacterial activities by lipophilic acid conjugation to D,L-amino acid-containing antimicrobial peptides: a plausible mode of action. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 14946-14956. [CrossRef]

- Malina, A.; Shai, Y. Conjugation of fatty acids with different lengths modulates the antibacterial and antifungal activity of a cationic biologically inactive peptide. Biochem J 2005, 390, 695-702. [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, N.A.; Haseman, J.R.; Tirrell, M.V.; Mayo, K.H. Acylation of SC4 dodecapeptide increases bactericidal potency against Gram-positive bacteria, including drug-resistant strains. Biochem J 2004, 378, 93-103. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephani, J.C.; Gerhards, L.; Khairalla, B.; Solov'yov, I.A.; Brand, I. How do Antimicrobial Peptides Interact with the Outer Membrane of Gram-Negative Bacteria? Role of Lipopolysaccharides in Peptide Binding, Anchoring, and Penetration. ACS Infect Dis 2024, 10, 763-778. [CrossRef]

- Avrahami, D.; Shai, Y. A new group of antifungal and antibacterial lipopeptides derived from non-membrane active peptides conjugated to palmitic acid. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 12277-12285. [CrossRef]

- Majerle, A.; Kidric, J.; Jerala, R. Enhancement of antibacterial and lipopolysaccharide binding activities of a human lactoferrin peptide fragment by the addition of acyl chain. J Antimicrob Chemother 2003, 51, 1159-1165. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, N.; Teng, D.; Mao, R.; Hao, Y.; Ma, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, J. Fatty acid modified-antimicrobial peptide analogues with potent antimicrobial activity and topical therapeutic efficacy against Staphylococcus hyicus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 105, 5845-5859. [CrossRef]

- Mak, P.; Pohl, J.; Dubin, A.; Reed, M.S.; Bowers, S.E.; Fallon, M.T.; Shafer, W.M. The increased bactericidal activity of a fatty acid-modified synthetic antimicrobial peptide of human cathepsin G correlates with its enhanced capacity to interact with model membranes. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2003, 21, 13-19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu-Kung, A.F.; Bozzelli, K.N.; Lockwood, N.A.; Haseman, J.R.; Mayo, K.H.; Tirrell, M.V. Promotion of Peptide Antimicrobial Activity by Fatty Acid Conjugation. Bioconjugate Chemistry 2004, 15, 530-535. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radzishevsky, I.S.; Rotem, S.; Zaknoon, F.; Gaidukov, L.; Dagan, A.; Mor, A. Effects of acyl versus aminoacyl conjugation on the properties of antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005, 49, 2412-2420. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakabayashi, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Hashimoto, K.; Teraguchi, S.; Takase, M.; Hayasawa, H. N-Acylated and D enantiomer derivatives of a nonamer core peptide of lactoferricin B showing improved antimicrobial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999, 43, 1267-1269. [CrossRef]

- Chu-Kung, A.F.; Nguyen, R.; Bozzelli, K.N.; Tirrell, M. Chain length dependence of antimicrobial peptide-fatty acid conjugate activity. J Colloid Interface Sci 2010, 345, 160-167. [CrossRef]

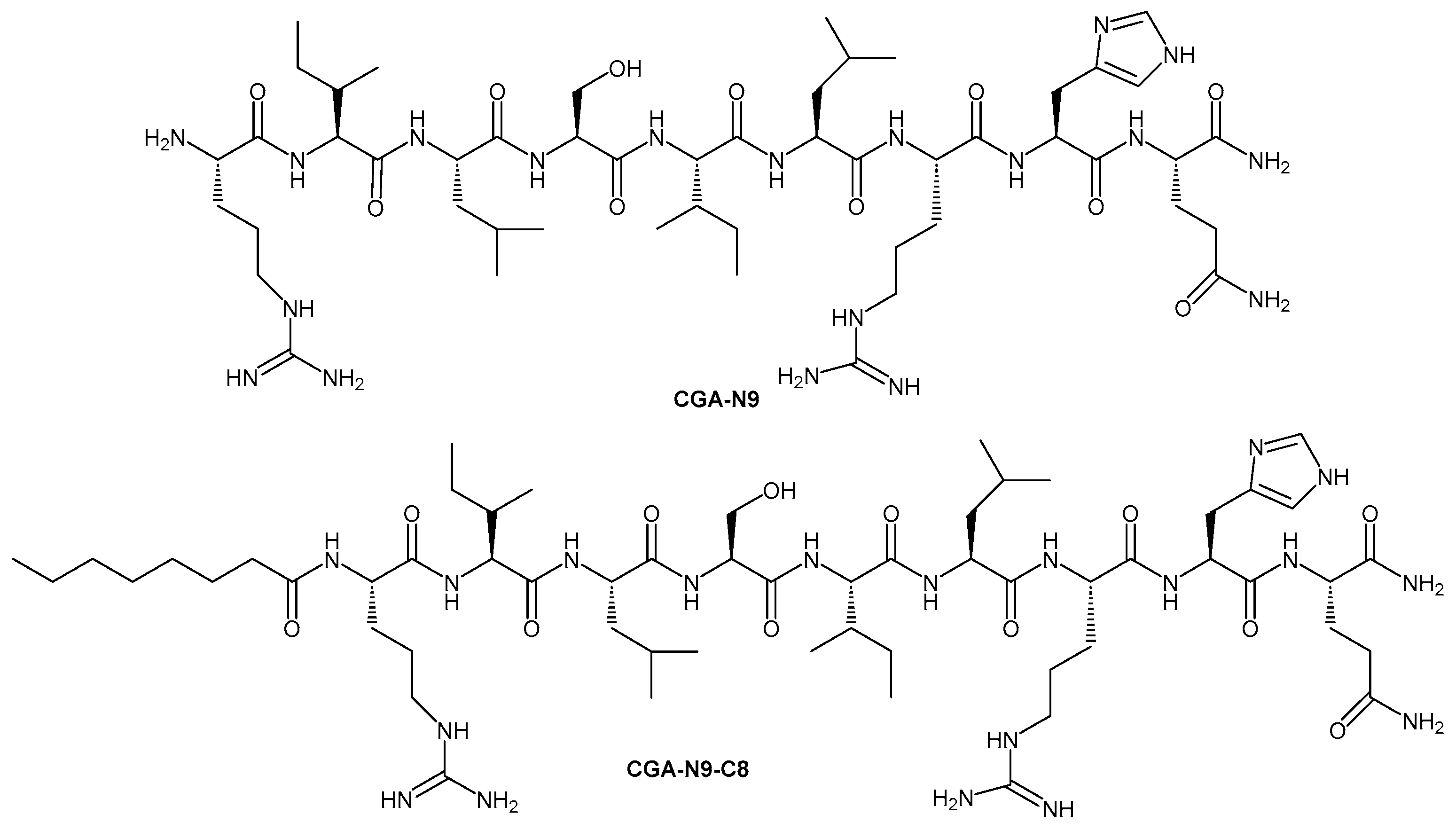

- Li, R.; Wang, X.; Yin, K.; Xu, Q.; Ren, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yi, Y. Fatty acid modification of antimicrobial peptide CGA-N9 and the combats against Candida albicans infection. Biochem Pharmacol 2023, 211, 115535. [CrossRef]

- Meir, O.; Zaknoon, F.; Cogan, U.; Mor, A. A broad-spectrum bactericidal lipopeptide with anti-biofilm properties. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 2198. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

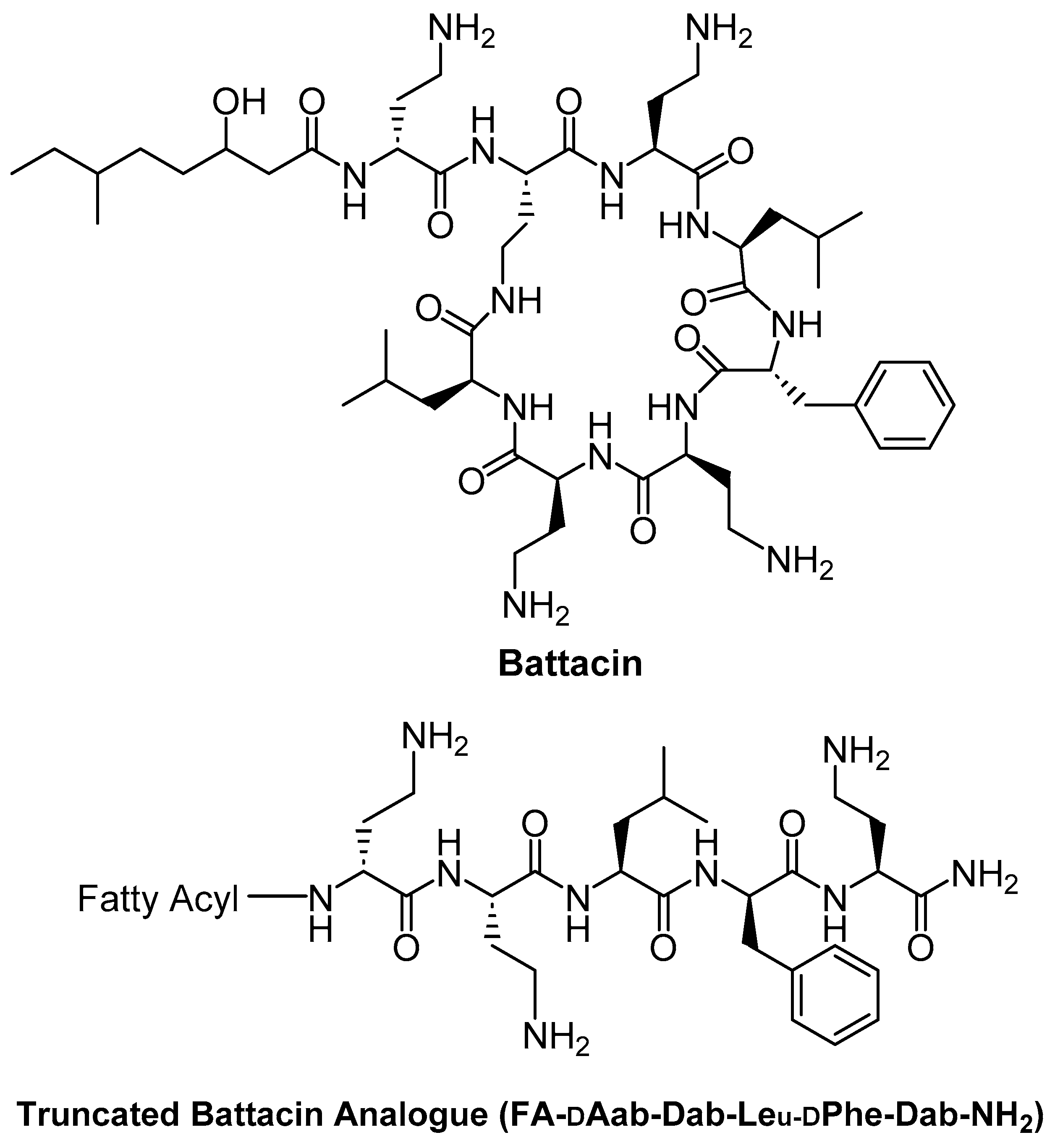

- Posa, L.; Tomek, P.; Lamba, S.; Sarojini, V.; Barker, D. Development of truncated Battacin antimicrobials featuring novel N-terminal fatty acids with an excellent safety profile. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2023, 96, 129535. [CrossRef]

- Hamman, J.H.; Enslin, G.M.; Kotzé, A.F. Oral delivery of peptide drugs: barriers and developments. BioDrugs 2005, 19, 165-177. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azeem, K.; Fatima, S.; Ali, A.; Ubaid, A.; Husain, F.M.; Abid, M. Biochemistry of Bacterial Biofilm: Insights into Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms and Therapeutic Intervention. Life (Basel) 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Willcox, M.D.P.; Dutta, D. Action of Antimicrobial Peptides against Bacterial Biofilms. Materials (Basel) 2018, 11. [CrossRef]

- Lamba, S.; Wang, K.; Lu, J.; Phillips, A.; Swift, S.; Sarojini, V. Polydopamine-Mediated Antimicrobial Lipopeptide Surface Coating for Medical Devices. ACS applied bio materials 2024, 7. [CrossRef]

- Casadidio, C.; Butini, M.E.; Trampuz, A.; Di Luca, M.; Censi, R.; Di Martino, P. Daptomycin-loaded biodegradable thermosensitive hydrogels enhance drug stability and foster bactericidal activity against Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2018, 130, 260-271. [CrossRef]

- K P, S.; Rajeswari, E.; Devadason, A.; Thiruvengadam, R. Exploring Quorum Sensing Loci and Biofilm Formation in Bacillus Isolates from Pigeonpea Rhizosphere. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2017, 6, 3252-3262. [CrossRef]

- Raskovic, D.; Alvarado, G.; Hines, K.M.; Xu, L.; Gatto, C.; Wilkinson, B.J.; Pokorny, A. Growth of Staphylococcus aureus in the presence of oleic acid shifts the glycolipid fatty acid profile and increases resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2025, 1867, 184395. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gier, M.G.; Bauke Albada, H.; Josten, M.; Willems, R.; Leavis, H.; van Mansveld, R.; Paganelli, F.L.; Dekker, B.; Lammers, J.-W.J.; Sahl, H.-G.; et al. Synergistic activity of a short lipidated antimicrobial peptide (lipoAMP) and colistin or tobramycin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis patients. MedChemComm 2016, 7, 148-156. [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Wei, Z.; Camesano, T.A. New antimicrobial peptide-antibiotic combination strategy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa inactivation. Biointerphases 2022, 17, 041002. [CrossRef]

- Ridyard, K.E.; Elsawy, M.; Mattrasingh, D.; Klein, D.; Strehmel, J.; Beaulieu, C.; Wong, A.; Overhage, J. Synergy between Human Peptide LL-37 and Polymyxin B against Planktonic and Biofilm Cells of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Reddersen, K.; Greber, K.E.; Korona-Glowniak, I.; Wiegand, C. The Short Lipopeptides (C(10))(2)-KKKK-NH(2) and (C(12))(2)-KKKK-NH(2) Protect HaCaT Keratinocytes from Bacterial Damage Caused by Staphylococcus aureus Infection in a Co-Culture Model. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Imperlini, E.; Massaro, F.; Buonocore, F. Antimicrobial Peptides against Bacterial Pathogens: Innovative Delivery Nanosystems for Pharmaceutical Applications. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 184.

- Makowski, M.; Silva Í, C.; Pais do Amaral, C.; Gonçalves, S.; Santos, N.C. Advances in Lipid and Metal Nanoparticles for Antimicrobial Peptide Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollmann, A.; Martínez, M.; Noguera, M.E.; Augusto, M.T.; Disalvo, A.; Santos, N.C.; Semorile, L.; Maffía, P.C. Role of amphipathicity and hydrophobicity in the balance between hemolysis and peptide-membrane interactions of three related antimicrobial peptides. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2016, 141, 528-536. [CrossRef]

- Dawgul, M.A.; Greber, K.E.; Bartoszewska, S.; Baranska-Rybak, W.; Sawicki, W.; Kamysz, W. In Vitro Evaluation of Cytotoxicity and Permeation Study on Lysine- and Arginine-Based Lipopeptides with Proven Antimicrobial Activity. Molecules 2017, 22, 2173. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzger, J.; Wiesmüller, K.H.; Schaude, R.; Bessler, W.G.; Jung, G. Synthesis of novel immunologically active tripalmitoyl-S-glycerylcysteinyl lipopeptides as useful intermediates for immunogen preparations. Int J Pept Protein Res 1991, 37, 46-57. [CrossRef]

- Spohn, R.; Buwitt-Beckmann, U.; Brock, R.; Jung, G.; Ulmer, A.J.; Wiesmüller, K.H. Synthetic lipopeptide adjuvants and Toll-like receptor 2--structure-activity relationships. Vaccine 2004, 22, 2494-2499. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavascki, A.P.; Nation, R.L. Nephrotoxicity of Polymyxins: Is There Any Difference between Colistimethate and Polymyxin B? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017, 61. [CrossRef]

- Ostaff, M.J.; Stange, E.F.; Wehkamp, J. Antimicrobial peptides and gut microbiota in homeostasis and pathology. EMBO Mol Med 2013, 5, 1465-1483. [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.S.; Junqueira, E.; Palma, C.; Viveiros, M.; Melo-Cristino, J.; Amaral, L.; Couto, I. Resistance to Antimicrobials Mediated by Efflux Pumps in Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics (Basel) 2013, 2, 83-99. [CrossRef]

- Pantosti, A.; Sanchini, A.; Monaco, M. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Future Microbiol 2007, 2, 323-334. [CrossRef]

- Sonbol, F.I.; El-Banna, T.E.; Abd El-Aziz, A.A.; El-Ekhnawy, E. Impact of triclosan adaptation on membrane properties, efflux and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli clinical isolates. J Appl Microbiol 2019, 126, 730-739. [CrossRef]

- Gontsarik, M.; Yaghmur, A.; Ren, Q.; Maniura-Weber, K.; Salentinig, S. From Structure to Function: pH-Switchable Antimicrobial Nano-Self-Assemblies. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019, 11, 2821-2829. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Niu, M.; Xue, T.; Ma, L.; Gu, X.; Wei, G.; Li, F.; Wang, C. Development of antibacterial peptides with efficient antibacterial activity, low toxicity, high membrane disruptive activity and a synergistic antibacterial effect. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2022, 10, 1858-1874. [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, S.P.; Lin, K.H.; Lin, W.C.; You, M.F.; Li, T.L.; Chen, J.Y. Rejuvenation of Meropenem by Conjugation with Tilapia Piscidin-4 Peptide Targeting NDM-1 Escherichia coli. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 29756-29764. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwangi, J.; Kamau, P.M.; Thuku, R.C.; Lai, R. Design methods for antimicrobial peptides with improved performance. Zool Res 2023, 44, 1095-1114. [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, A.; Hung, A.; Qiao, G.; Hajizadeh, E. Lipidation-induced bacterial cell membrane translocation of star-peptides; 2025.

- Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Kang, Y.; Pan, P.; Ge, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J.; et al. Discovery of antimicrobial peptides with notable antibacterial potency by an LLM-based foundation model. Sci Adv 2025, 11, eads8932. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.; Zeng, Z.; Xiong, X.; Huang, B.; Tang, L.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Tang, X.; Shao, G.; Huang, X.; et al. AMPGen: an evolutionary information-reserved and diffusion-driven generative model for de novo design of antimicrobial peptides. Communications Biology 2025, 8, 839. [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Puga, M.D.C.; Plisson, F. Structure-aware machine learning strategies for antimicrobial peptide discovery. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 11995. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, D.P.; Tripathi, A.K.; Thakur, A.K. Innovative Strategies and Methodologies in Antimicrobial Peptide Design. J Funct Biomater 2024, 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eugster, R.; Orsi, M.; Buttitta, G.; Serafini, N.; Tiboni, M.; Casettari, L.; Reymond, J.-L.; Aleandri, S.; Luciani, P. Leveraging machine learning to streamline the development of liposomal drug delivery systems. Journal of Controlled Release 2024, 376, 1025-1038. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antimicrobial Peptide (origin/description) | Fatty Acid Conjugated | Conjugation Method | Target Organisms | Effects on Activity & Stability | Reference |

| B1 peptide (16-residue cationic AMP) | Hexanoic (C6) and Octanoic (C8) acids | N-terminal acylation (amide bond) | S. aureus, K. pneumoniae (Gram+ and Gram–) | Significantly enhanced antimicrobial activity; improved serum stability and biocompatibility compared to parent peptide. | [48] |

| CGA-N9 (9-aa fragment of Chromogranin A) | Octanoic acid (C8) | N-terminal acylation (solid-phase synthesis) | C. albicans (yeast; planktonic and biofilm) | Optimal anti-Candida efficacy; highest biofilm inhibition and eradication; strong stability against proteolysis; excellent biosafety profile. | [72] |

| Lfcin4 & Lfcin5 (16-aa bovine lactoferricin derivatives) | Linoleic acid (C18:2, unsaturated) at N-terminus (C-terminal amidation) | N-terminal acylation + C-terminal NH2 | S. hyicus (Gram+; pig pathogen) in an infected mouse model | Improved antibacterial activity (MIC 3–6 µM vs up to 60 µM in parent peptides); in vivo efficacy with membrane disruption and leakage in bacteria; extended duration of action. | [66] |

| Anoplin analogue (Ano-D4,7) (10-aa peptide with D-lys at positions 4,7) | C8–C12 saturated fatty acids (e.g., octanoic, decanoic, lauric) on the side chain | Side-chain acylation on D-amino acid (via amide bond) | Multiple MDR bacteria (e.g., drug-resistant E. coli, S. aureus); also tested against biofilms | Excellent broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, especially against MDR strains; fatty chain length 8-12 gave the best results: potent antibacterial and anti-biofilm effects, high salt/serum stability, and low propensity for resistance development. | [47] |

| Truncated Battacin analogue (cyclic lipopeptide antibiotic derivative, linear form) | Novel fatty acids (modified long-chain lipids) at the N-terminus | N-terminal acylation (on linear peptide, replacing cyclic lipidated core) | S. aureus (including MRSA); Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, P. aeruginosa, etc.) | Maintained or improved broad antibacterial activity (comparable to polymyxin/battacin); significantly improved safety, e.g., ~2.3-fold higher LD50 in mice vs polymyxin B. Effective against MRSA and showed an excellent safety profile (low host cell toxicity). | [74] |

| Magainin analogue & [D]-K5L7 (inactive short peptides) | Undecanoic (C11) and Palmitic (C16) acids | N-terminal acylation (amide) | Gram+ bacteria, Gram– bacteria, yeast/fungi (C. neoformans, Candida) | Inactive peptides became highly potent: broad-spectrum antibacterial and antifungal activity was achieved. Lipopeptides caused increased membrane permeability in bacterial and fungal model membranes. Optimal chain (~C11–C12) maximized activity. | [60] |

| Lactoferricin B core (9-mer) RRWQWRMKK | N-acyl groups (various lengths) and D-amino acid substitution | N-terminal acylation; D-enantiomer analogues | E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus; C. albicans, Trichophyton (fungi) | N-acylated and/or D-form peptides showed improved antimicrobial activity across bacteria and fungi compared to the native peptide. Demonstrated one of the earliest proofs that fatty-acylation enhances AMP efficacy against diverse microbes. | [70] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).